Abstract

People and societies seek to combat harmful events. However, because resources are limited, every wrong righted leaves another wrong left unchecked. Responses must therefore be calibrated to the magnitude of the harm. One underappreciated factor that affects this calibration may be people’s oversensitivity to intent. Across a series of studies, people saw intended harms as worse than unintended harms, even though the two harms were identical. This harm-magnification effect occurred for both subjective and monetary estimates of harm, and it remained when participants were given incentives to be accurate. The effect was fully mediated by blame motivation. People may therefore focus on intentional harms to the neglect of unintentional (but equally damaging) harms.

Keywords: morality, judgment, motivation, social cognition

Motivations induce biases that help people see what they want to see (Kunda, 1990). This process can be described via an analogy with adversarial legal systems, in which lawyers (like motivational forces) prefer one verdict over another. They therefore restructure or even distort the facts in a way that tips the judge (or judgment processes) toward the desired conclusion. However, even as motivated decision makers act as lawyers, they tend to see themselves as impartial judges (Ditto, Pizarro, & Tannenbaum, 2009). This “illusion of objectivity” (Pyszczynski & Greenberg, 1987) allows motivated reasoning to subtly affect people’s genuine beliefs.

Judgments about moral and immoral acts may be especially subject to such motivational biases (Ditto et al., 2009). Most moral judgments are emotional, complex, and subjective—precisely the conditions under which the effects of motivated reasoning tend to be largest (Ditto & Boardman, 1995; Dunning, Leuenberger, & Sherman, 1995). However, some motivations may also be sufficiently powerful to influence the perception of straight- forward, objective information. Here, we examine whether moral motivations might cause people to see certain kinds of harms—specifically, intentional harms—as worse than they actually are.

Studies on belief in a just world (Lerner, 1965), defensive attributions (Shaver, 1970), retributive justice (Darley & Pittman, 2003), criminal responsibility (Gebotys & Dasgupta, 1987), and moral psychology (Gray & Wegner, 2010; Haidt & Kesebir, 2010; Knobe et al., 2012) all con- verge to show that when people detect harm, they become motivated to blame someone for that harm. This demonstrably powerful motivation has been variously indexed as the need to assign blame, to express moral condemnation, and to dole out punishment (Alicke, 2000; Haidt, 2001; Robinson & Darley, 1995). Often, these three needs co-occur, and they may represent different, but related, components of humans’ moral response to harm. For convenience, we refer to these components collectively as blame motivation, and we suggest that people seek (though not always consciously) to satisfy this motivation when confronted with harm.

If people (acting as motivated lawyers) want to blame harm-doers (Alicke & Davis, 1990), what evidence could they emphasize (or distort) to make their case more compelling? We suggest that one tactic would be to imply that harm-doers caused more harm than they actually did. To satisfy blame motivation, one’s inner lawyer might marshal more evidence for harm than actually exists. From this line of reasoning, we argue that harmful acts that lead to especially large amounts of blame motivation also lead to exaggerated perceptions of harm. But what kinds of harmful acts are especially likely to induce blame motivation?

Though we suspect that this question has several answers, numerous behavioral (and, recently, neuroscientific) experiments have demonstrated that intentional harms make people want to blame, condemn, and punish more than unintentional harms do (Alicke, 1992; Darley & Pittman, 2003; Young & Saxe, 2009). For example, people are approximately twice as likely to punish someone who intentionally cheated (by not reciprocating in an economic game) than to punish someone who made an innocent mistake (because of inexperience with the game; Hoffman, McCabe, & Smith, 1998). People are notoriously sensitive to harmful intentions (Gollwitzer & Rothmund, 2009), and even exposure to fictional characters with harmful intentions can change subsequent trust behavior in real life (Rothmund, Gollwitzer, & Klimmt, 2011). If, as we propose, intent leads to blame motivation, and blame motivation, in turn, leads to increased perceived harm, it follows that harms that are committed intentionally should be seen as worse than they actually are, and as worse than identical harms committed unintentionally.

This is the main hypothesis we aimed to test in the present research. We further predicted that the effect of intentionality on perceived harm would be mediated by blame motivation. In Studies 1 through 3, we presented participants with simple vignettes that described harmful events and manipulated whether those harms were framed as intentional or unintentional (while holding constant the actual harms). Participants then judged how much harm befell the victims. In Studies 4 and 5, we tested whether this bias would remain even when objective, accurate information about the amount of harm was readily available, and even when participants were given incentives to be accurate.

Participants

Participants (N = 675) were recruited using Amazon Mechanical Turk and then redirected to an experimental Web site. They were paid standard rates ranging from 20¢ to $2.00 for participating in these studies. Recruitment was limited to the United States. Current research suggests that samples recruited via Mechanical Turk are more demographically and cognitively representative of national distributions than are traditional student samples, and that data reliability is at least as good as that obtained via traditional sampling (e.g., Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Mason & Suri, 2012; Paolacci, Chandler, & Ipeirotis, 2010). Participants who had completed any previous study in this line of work were automatically prevented from accessing the recruitment page. Of the 675 who were recruited, 39 participants failed to complete the task. Of the remaining 636 participants, 14% were excluded for failing the manipulation check or basic checks for meaningful responses. For complete information on these checks and the number of persons excluded by each one, see Participant Exclusion Criteria in the Supplemental Material available online.

Study 1 - Method

Participants (N = 80) in our first study read a vignette about a CEO of a small company where employees’ compensation was partially based on company profits (i.e., profit sharing). The CEO made an investment that performed poorly and therefore cost his employees money. Participants were randomly assigned to either the intentional-harm condition (n = 39) or the unintentional-harm condition (n = 41), which differed in whether the vignette specified that the CEO harmed his employees intentionally (he thought that “they would work harder to increase profits in the future if they made less money now”) or unintentionally (he thought the investment was a good one that would make money, but “the investment failed”). (See Vignettes in the Supplemental Material for the full texts used in both conditions.)

Although this framing explaining the CEO’s intents varied across conditions, the actual harms that participants were asked to judge were identical:

The employees made less money than they otherwise would have. This caused them some anxiety and made paying off credit cards and taking family vacations harder for them. Two employees saw a minor dip in their credit scores because of late payments—though nobody suffered truly dire financial hardship or came close to losing their home or their car or anything.

To avoid the confound that the employees in the intentional-harm condition would have felt more victimized (which would have made their harm actually worse; Gray & Wegner, 2008), we stipulated that the employees in both conditions were unaware of the investment. The company made less money, and therefore its profit- sharing employees also made less money, but the employees had no reason to suspect foul play, incompetence, or any other cause more in one condition than in the other. Thus, the harms to the employees were truly identical (both financially and psychologically) in the two conditions.

Nonetheless, we predicted that the harms would be judged as different. Because our hypotheses concerned harm in general, we began by asking participants about harm in general (specific, objectively quantifiable harms were examined in Studies 4 and 5). Participants were asked: “How much harm would you say Terrance’s [the CEO’s] investment in the software development project did to the employees?” Responses were made on a sliding scale ranging from 0 (none) to 100 (the most harm Terrance’s actions as CEO could possibly cause them). Thus, all participants judged the same act (the investment) by the same person (the CEO) and the same resulting harm to the same people (the employees). Nonetheless, we predicted that participants would see the harms as greater when framed as intentional rather than unintentional, and that this effect would be due to (fully mediated by) differences in blame motivation. Following our earlier definition of blame motivation (desire to blame, morally condemn, and punish), we assessed this construct via a three-item (∝ = .86) index (sliding scale from 0 to 100): “To what extent do you think Terrance deserves blame for making the investment?”; “To what extent do you think Terrance should be morally condemned for making the investment?”; and “To what extent would you want Terrance to be punished for making the investment?”

Results

Intent

A manipulation check confirmed that participants indeed saw the harm as more intentional in the intentional-harm condition (M = 65.13, SD = 36.65) than in the unintentional-harm condition (M = 4.20, SD = 9.81), p < .001, d = 2.27 (scale from 0 through 100).

Harm

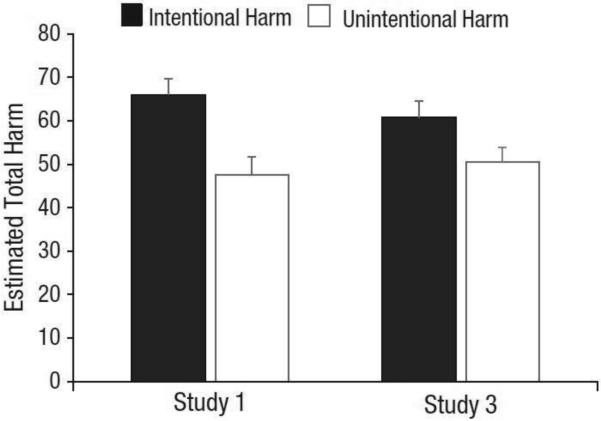

Our key prediction was confirmed. Although the harms to the employees were described identically in the two conditions, participants thought that the employees were more harmed in the intentional-harm condition (M = 65.95, SD = 23.20) than in the unintentional-harm condition (M = 47.59, SD = 26.40), p = .001, d = 0.74 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Results from Studies 1 and 3: perceived harm to employees (scale from 0 through 100) in the intentional- and unintentional-harm conditions. Error bars represent standard errors.

Blame motivation

As predicted, participants were more motivated to blame Terrance when he had harmed the employees intentionally rather than unintentionally, t(78) = 8.74, p < .001. (The difference between conditions was also significant when ratings for each blame- motivation item were examined separately, ps < .001.) Moreover, blame motivation fully mediated the effect of perceived intentionality on magnitude of perceived harm, Sobel’s Z = 5.00, SE = 0.08, p < .001. In contrast, the alternative model, with perceived harm leading to blame motivation rather than vice versa, was a worse description of the data, and a bootstrapping analysis fully corroborated these findings (see Supplemental Mediation Analyses in the Supplemental Material).

Discussion

Thus, Study 1 provided initial support for the hypothesis that people see intended harms as worse than (identical) unintended harms. But why? Our theoretical account suggests that intent provoked blame motivation and that, because of their motivation to build a case against the CEO, participants exaggerated how much harm had been done. Mediation analyses sup- ported this model; however, an alternative possibility exists. Legal scholars point out that CEOs who act criminally or immorally not only harm individuals but also create broader social harms, to which people are sensitive (e.g., Cohen, 1988). From this perspective, the CEO’s actions in this study would have been perceived as a betrayal of public trust—a harm against the fabric of society in general (Darley & Huff, 1990). This perceived harm to society in general may have leaked into participants’ ratings of the harms to a circumscribed set of specific employees.

However, it should not be assumed that participants held this view about harm to society, or that they were incapable of separating harms to society from harms to specific individuals. A conservative test as to whether different judgments of harm to society could have produced the effects in Study 1 would be to test whether such differences in judgment exist at all. If not, then it would be difficult to argue that they explain the results.

Study 2

We therefore reproduced Study 1 with only one change: Instead of asking participants how much harm Terrance’s investment in the software development project did to the employees, we asked, “How much harm would you say Terrance’s investment in the software development project did to society in general?”

Although intentionality was again manipulated effectively (intentional harm: n = 46, M = 71.70, SD = 34.73; unintentional harm: n = 47, M = 3.85, SD = 10.19, p < .001), and the blame-motivation scale remained reliable (∝ = .81), there was no magnification of harm—that is, no effect of intent on perceived harm to society (intentional harm: M = 45.63, SD = 24.51; unintentional harm: M = 38.40, SD = 28.34), p = .19.

It therefore appears unlikely that different perceptions of harm to society explain the effects observed in Study 1, as no such differences exist. However, it could be argued that Study 2 might simply constitute a failure to replicate. Yet another possibility is that participants in Study 1 (consciously or unconsciously) accounted for future harms in the intentional-harm condition, reasoning that the CEO who intentionally harmed his employees once (and did not get caught) might do so again, thus causing more harm. We conducted Study 3 to test these two possibilities, directly replicating the intentional- and unintentional- harm conditions from Study 1 (to address the “failure to replicate” alternative hypothesis) and adding a third condition in which future harm was not a factor (to address the “future harms” alternative hypothesis).

Study 3

Procedures were identical to those in Study 1 for participants in the intentional-harm (n = 41) and unintentional- harm (n = 38) conditions. All effects observed in Study 1 were replicated. The intent-magnifies-harm effect was again significant, p = .04, d = 0.48, and the mean harm ratings in both conditions were statistically identical to those observed in Study 1—intentional harm: M = 61.26, SD = 23.67, p = .29; unintentional harm: M = 50.50, SD = 21.18, p = .59 (see Fig. 1). Participants also expressed more blame motivation in the intentional-harm condition than in the unintentional-harm condition, t(77) = 8.26, p < .001. The blame-motivation index was again reliable (∝ = .91) and again fully mediated the effect of intentionality on perceived harm, Z = 3.19, SE = 0.04, p = .001. Bootstrapping analyses again corroborated these results, and the results of both mediational approaches supported the predicted model (intent → blame motivation → harm) over the alternative model (intent → harm → blame motivation; see Supplemental Mediation Analyses in the Supplemental Material).

As noted, to test whether participants’ harm ratings might have reflected anticipated future harms, we also ran a third condition: the intentional-harm/fired condition (n = 42). This was identical to the intentional-harm condition except that the vignette explicitly precluded the possibility of the CEO perpetrating additional harms against the employees by stipulating that he was caught and fired for his actions (see Vignettes in the Supplemental Material). This change, however, made no difference in perceived harm (intentional harm: M = 61.05; intentional harm/fired: M = 61.57), p = .96. This pattern of results suggests that the observed harm-magnification effect was not an artifact of anticipated future harms.

Studies 1–3: Summary and Limitations

Studies 1 through 3 provided initial evidence for the intent-magnifies-harm effect and its proposed mechanism, while ruling out some possible confounds. However, they also left at least two questions unresolved.

First, does this effect hold for harms that are objectively quantifiable and ecologically meaningful? Because our hypotheses concerned harm in general, it seemed appropriate to begin by asking participants “how much harm” they perceived without forcing upon them any specific definition of harm. However, it is unclear what “61.5 units of harm” (for example) means (Blanton & Jaccard, 2006). Second, what is the direction of the effect? Our theoretical account predicts an exaggeration of intentional harms. However, Studies 1 through 3 could not test directionality, as there was no “ground truth” as to how much harm actually occurred. In Studies 4 and 5, we aimed to address these questions.

We also sought to generalize our findings beyond comparisons of two human harm-doers. In Studies 4 and 5, we compared a disaster caused by human intent with the same disaster caused by nature (no intent). This comparison is particularly relevant to ongoing debates concerning the allocation of government funds to mitigate disasters that feel highly intentional (e.g., terrorism) relative to those that do not (see the General Discussion).

Study 4 – Method

Participants read a vignette that described a group of people suffering from a water shortage. The proximal cause of the shortage (a specific river drying up) and all of the consequences (crops lost, etc.) were identical across conditions, but the conditions (randomly assigned) varied in how the cause of the damages was framed (see Vignettes in the Supplemental Material). Participants in the intentional-harm condition (n = 29) read that the river dried up “because a man who lived in a nearby town diverted the flow” with the intent to cause the harm that occurred, whereas participants in the unintentional-harm condition (n = 26) read that the shortage was naturally occurring (“due to a lack of rain”).

After reading the vignette, participants were instructed that they would see all of the harms caused by the drought (in dollars) and then estimate how much total harm had occurred (in dollars). They were warned that the harms would be presented quickly, and that they should pay close attention. Next, they saw seven harms that resulted from the water shortage (e.g., “medical supplies used: $80.00”). These harms appeared for 2,000 ms each, separated by 300 ms, and in a fixed order (see Fig. S1 in the Supplemental Material). Immediately after viewing these numbers, participants were asked to estimate their sum. The list of harms was identical in the two conditions.

Results

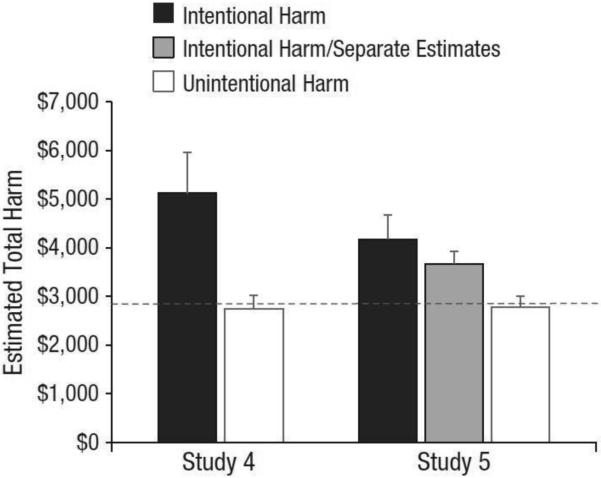

Participants in the unintentional-harm condition estimated the drought damage accurately; their average estimate of $2,753 (SD = 4,518.28) was close to the correct answer of $2,862, t(25) = 0.40, p = .70. By comparison, participants who thought that those same harms were intentional overestimated their sum by a substantial mar- gin (M = $5,120, SD = 1,396.32), t(28) = 2.69, p = .01, d = 0.50 (see Fig. 2). The two estimates were also significantly different from one another, t(33.85) = 2.68, p = .01, d = 0.71 (corrected for unequal variances). These results confirm the hypothesized direction of the effect, showing that intentional harms were magnified, whereas unintentional harms were assessed accurately. Moreover, the effect in dollars (about $5,100 vs. about $2,800) is more interpretable than the effects observed using the arbitrary metric in Studies 1 through 3.

Fig. 2.

Results from Studies 4 and 5: estimated harm in the intentional-harm, unintentional-harm, and intentional-harm/separate-estimates (Study 5 only) conditions. The dashed line represents the correct answer. Error bars represent standard errors.

The magnitude of this effect is perhaps surprising given the apparent straightforwardness of the task (i.e., estimating the sum of seven numbers). Results from the unintentional-harm condition suggest that people are capable of estimating the listed harms accurately (at least on average), so why did they grossly overestimate the harms in the intentional-harm condition? Perhaps participants misunderstood the instructions and added punitive damages or fines to their estimates. Or perhaps they understood the instructions but, in the absence of any incentive for accuracy, chose to express their blame motivation through a deliberately inflated estimate. To test these possibilities, we conducted a fifth study, in which we replicated the procedure of Study 4 except that we provided financial and competitive incentives for accuracy and also included a third condition in which participants had to explicitly separate punitive damages from their estimates of the objective harms.

Study 5

The materials and procedure for the intentional-harm and unintentional-harm conditions in Study 5 were identical to those in Study 4, except that participants were told that the 5% of participants who made the most accurate estimates would have their pay for participation multiplied by 10. Again, participants in the unintentional-harm condition (n = 65) estimated the damage accurately (M = $2,773, SD = 1,932.66), t(64) = 0.38, p = .71, but participants in the intentional-harm condition (n = 71) overestimated the damage (M = $4,176, SD = 4,194.62), t(70) = 2.64, p = .01, d = 0.31 (see Fig. 2). Also as in Study 4, the estimates of the two groups were significantly different from one another, t(100.38) = 2.54, p = .01, d = 0.43 (corrected for unequal variances). Although the magnitude of the bias in the intentional-harm condition was somewhat smaller when people were paid to be accurate than when they were given no such incentive, neither of the two groups’ estimates in Study 5 differed significantly from the corresponding estimate in Study 4—intentional-harm condition: p = .32; unintentional-harm condition: p = .96. Thus, even with financial and competitive incentives to be accurate, participants still saw intentional harms as larger than they actually were.

Finally, 61 participants completed the intentional-harm/separate-estimates condition. These participants were presented with the same vignette used in the intentional-harm condition. However, instead of promoting accuracy by using monetary incentives, we sought to promote accuracy by eliminating any room for discretionary adjustments of the estimate. Participants were asked to provide two distinct monetary values: their estimate of the objective sum of the harms and their punitive assessment (counterbalanced order). In one box, we asked them to “estimate the total of the damages, in dollars (the sum of the numbers you just saw).” In a separate box, they were asked to indicate “how much extra money should that person have to pay in fines/penalties/ compensation beyond the actual costs as shown (that is, beyond the sum of the numbers you just saw)?” The estimates of objective harm (M = $3,627, SD = 2,001.90) were still significantly larger than the correct answer, t(60) = 2.98, p = .004, d = 0.38, and were similar (p = .35) to those of the incentivized participants who did not receive these explicit instructions. Moreover, these biased harm estimates were positively correlated with punitive assessments, r(54) = .39, p = .003, which provides further evidence that biases in participants’ objective estimates were not due to some participants “moving” desired punitive damages into their estimates of objective damages. In sum, although we suspect that the very large effect observed in Study 4 may have been artificially inflated by the inclusion of punitive damages in harm ratings, it seems unlikely that the same concern applies to Study 5.

General Discussion

These five studies suggest that people overestimate the magnitude of intentional harms. Studies 1 through 3, which allowed participants to apply their own definition of “harm,” show that the intent-magnifies-harm effect emerges when people judge identical actions that are committed by identical people and result in identical harms to identical victims. They also indicate that the effect is not an artifact of outrage about harm to society in general or of anticipated future harms. Studies 1 and 3 show that the effect is reliably mediated by blame motivation. Studies 4 and 5 demonstrate the directionality of the effect and its durability in the face of incentives to be accurate.

These findings relate to a number of ongoing lines of research. Intent is among the most important theoretical constructs for “blame experts,” that is, psychologists, philosophers, and legal scholars concerned with blame and moral judgment (Borgida & Fiske, 2008; Fiske, 1989). At a mechanistic level, the present work comports well with Alicke’s (2000) culpable-control model of blame assessment, which prioritizes motivational factors in shaping the evaluation of evidence. At the same time, this work suggests patterns of causality that are different from those demonstrated by the culpable-control model, showing that blame motivation can shape the very perceptions of harm that were supposed to have caused that motivation. Similarly, whereas the Knobe effect (Knobe, 2003) demonstrates that people are more likely to see harmful than helpful acts as intentional, the present work demonstrates that people are likely to see intentional acts as more harmful than unintentional ones.

The present work also aligns well with previous research on distortions of long-term memory. For example, in an experiment by Pizarro, Laney, Morris, and Loftus (2006), participants learned about a man who had walked out on a restaurant bill. The researchers then presented several pieces of postevent information (Loftus, 1997), to influence recall for the event. Specifically, they described the restaurant patron either as a good, caring person acting under extraordinary personal circumstances (he received a phone call saying that his daughter was ill, had to rush to the hospital, and paid the bill later, calling from the hospital to apologize profusely) or as a morally loathsome individual who walked out on as many restaurant bills as possible for fun, despite having plenty of money, and did so after mistreating the waitstaff and other restaurant patrons. One week later, when participants were given a surprise memory test, those who had been given negative moral information misremembered some of the items on the unpaid restaurant bill as being more expensive than they had actually been. Interpreting the specific impact of moral information in this study is complicated by the fact that an identical effect emerged in the control condition, in which no information on moral character was given. Nonetheless, this result is broadly consistent with many previous studies showing that suggestive postevent information can cause people to misremember events over time (Loftus, 1997). The present research extends this idea, showing that neither postevent information nor lengthy windows for forgetting seem to be necessary to produce such distortions, while also providing evidence for an underlying mechanism and for robustness in the face of accuracy incentives.

Given that the phenomenon under examination makes people less accurate in their judgments, how might it be psychologically or socially functional? First (as we have said), seeing more harm than is actually present can be psychologically functional in helping people to satisfy the motivation to blame. Second, because people live in hyper-interdependent societies, and have from their evolutionary beginnings (Kurzban & Neuberg, 2005), it is socially functional for them to be extremely sensitive to individuals intentionally harming one another (Hoffman et al., 1998). This oversensitivity to intentional harms helps protect social groups from malfeasant individuals, but may also cause individuals to overestimate the magnitudes of intentional harms.

One policy implication arising from this work is that perceived intent may inflate legal penalties for property damage. This suggestion, which has implications for tort law and insurance regulations, is supported by “an unpredicted and potentially interesting effect” observed by Darley and Huff (1990, p. 181). They found that deliberate physical damages to property were judged as more expensive than accidental damages. The authors noted, however, that because this comparison was not the original goal of the study in which the effect was found, the experimental design left room for multiple interpretations (including that damage assessments were mixed with punitive damages). Also, in the only study designed to test this comparison specifically, the result was not statistically significant. Still, the findings are potentially important, because they point to a discrepancy between the way humans beings actually reason and the underlying assumptions of the legal system.

Our studies may also have implications for under- standing policy judgments regarding government budgets. Because nations have finite resources, every wrong righted leaves another wrong left unchecked. It has been argued (Gilbert, 2011) that resources are overallocated to harms that feel highly intentional (e.g., terrorism), even in the face of data suggesting that humanitarian interests might be better served by dedicating some of these resources to combating other harms (e.g., global warming). The present work suggests a novel psychological mechanism for this phenomenon: Intentional harms receive more funding and attention not only because of political imperatives and moral reactionism (Gilbert, 2011), but also because intent magnifies the perceived harms themselves.

Of course, there are many reasons why political power holders might invest more heavily in fighting terrorism than in other kinds of interventions. Some of these rea- sons are likely very sensible, and some are likely less so. Separating these two kinds of reasons is important for calibrating responses to global events. The present work suggests that one underappreciated factor currently affecting this calibration may be people’s oversensitivity to intentional harms, which leads them to overestimate the magnitude of those harms (perhaps even when they are incentivized to be accurate). Given the dollars and humanitarian issues at stake, this possibility may be worth additional investigation.

Supplementary Material

References

- Alicke MD. Culpable causation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:368–378. [Google Scholar]

- Alicke MD. Culpable control and the psychology of blame. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:556–574. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alicke MD, Davis TL. Capacity responsibility in social evaluation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1990;16:465–474. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton H, Jaccard J. Arbitrary metrics in psychology. American Psychologist. 2006;61:27–41. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgida E, Fiske ST. Beyond common sense: Psychological science in the courtroom. Wiley-Blackwell; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA. Corporate crime and punishment: A study of social harm and sentencing practice in the Federal Courts, 1984-1987. American Criminal Law Review. 1988;26:605–660. [Google Scholar]

- Darley JM, Huff CW. Heightened damage assessment as a result of the intentionality of the damage-causing act. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1990;29:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Darley JM, Pittman TS. The psychology of compensatory and retributive justice. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2003;7:324–336. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditto PH, Boardman AF. Perceived accuracy of favorable and unfavorable psychological feedback. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1995;16:137–157. [Google Scholar]

- Ditto PH, Pizarro DA, Tannenbaum D. Motivated moral reasoning. In: Ross BH, Bartels DM, Bauman CW, Skitka LJ, Medin DL, editors. Psychology of learning and motivation: Vol. 50. Moral judgment and decision making. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2009. pp. 307–338. Series Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning D, Leuenberger A, Sherman DA. A new look at motivated inference: Are self-serving theories of success a product of motivational forces? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST. Examining the role of intent: Toward understanding its role in stereotyping and prejudice. In: Uleman J, Bargh J, editors. Unintended thought: The limits of awareness, intention, and control. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1989. pp. 253–283. [Google Scholar]

- Gebotys R, Dasgupta B. Attribution of responsibility and crime seriousness. The Journal of Psychology. 1987;121:607–613. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1987.9712690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D. Buried by bad decisions. Nature. 2011;474:275–277. doi: 10.1038/474275a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer M, Rothmund T. When the need to trust results in unethical behavior: The Sensitivity to Mean Intentions (SeMI) model. In: De Cremer D, editor. Psychological perspectives on ethical behavior and decision making. Information Age; Charlotte, NC: 2009. pp. 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gray K, Wegner DM. The sting of intentional pain. Psychological Science. 2008;19:1260–1262. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K, Wegner DM. Blaming God for our pain: Human suffering and the divine mind. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2010;14:7–16. doi: 10.1177/1088868309350299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review. 2001;108:814–834. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.4.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, Kesebir S. Morality. In: Fiske S, Gilbert D, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of social psychology. 5th Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2010. pp. 797–832. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman E, McCabe K, Smith V. Behavioral foundations of reciprocity: Experimental economics and evolutionary psychology. Economic Inquiry. 1998;36:335–352. [Google Scholar]

- Knobe J. Intentional action and side effects in ordinary language. Analysis. 2003;63:190–193. [Google Scholar]

- Knobe J, Buckwalter W, Nichols S, Robbins P, Sarkissian H, Sommers T. Experimental philosophy. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012;63:81–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunda Z. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:480–498. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzban R, Neuberg L. Managing in-group and out- group relationships. In: Buss D, editor. Handbook of evolutionary psychology. Wiley; New York, NY: 2005. pp. 653–675. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner M. Evaluation of performance as a function of performer’s reward and attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1965;26:415–419. doi: 10.1037/h0021806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus EF. Creating false memories. Scientific American. 1997;277:70–75. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0997-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W, Suri S. Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods. 2012;44:1–23. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolacci G, Chandler J, Ipeirotis P. Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgment and Decision Making. 2010;5:411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro DA, Laney C, Morris EK, Loftus EF. Ripple effects in memory: Judgments of moral blame can dis- tort memory for events. Memory & Cognition. 2006;34:550–555. doi: 10.3758/bf03193578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J. Toward an integration of cognitive and motivational perspectives on social inference: A biased hypothesis-testing model. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 20. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1987. pp. 297–340. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PH, Darley JM. Justice, liability, and blame: Community views and the criminal law. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rothmund T, Gollwitzer M, Klimmt C. Of virtual victims and victimized virtues: Differential effects of experienced aggression in video games on social cooperation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2011;37:107–119. doi: 10.1177/0146167210391103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaver KG. Defensive attribution: Effects of severity and relevance on the responsibility assigned for an accident. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1970;14:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Saxe R. An fMRI investigation of spontaneous mental state inference for moral judgment. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2009;21:1396–1405. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.