Although parents and parenting issues are central to child health practice, research, and policy, significant gaps in current knowledge exist regarding the nature of parenting. Recent meta-analyses have verified the role of parents in achieving outcomes related to physical, socio-emotional, and cognitive well-being of their children (Barlow, Smailagic, Huband, Roloff, & Bennett, 2012; Belsky & deHaan, 2011; Scott, 2012). In fact, parenting has been deemed most important to our public health because of the far-reaching influence of the parent-child relationship (Gage, Everett, & Bullock, 2006). The tasks involved in parenting and the ability of the parent to communicate have been found especially important to children's physical, socio-emotional, and psychological outcomes (Hibbard et al., 2012; Sanders, 2012). Parents derive meaning and connection from the tasks associated with parenting and communication with their children, yet much of this work is invisible and occurs in the day-to-day activities of caring for young children.

Parenting young children is labor-intensive and requires a great deal of hands-on physical care, attention to safety, and interpretation of cues. Thus, caring for a newborn or young child can be physically exhausting. The child's communicative abilities and needs change over time: Therefore, the parents must accommodate this evolution by changing how they communicate with the child and how they interpret the child's communication. Because of this, tasks and communication often serve as the focus of evaluation and intervention research with clinical populations of children (Horowitz et al., 2001; Horowitz et al., 2013; Sanders, 2012). While more is known about the antecedents to or consequences of parenting, gaps in the literature exist around the normative tasks or processes of parenting. For example, more is known about the influence of a parent's personality on parenting and the effects of harsh parenting, than is known about the ordinary work and essential components of parenting, specifically tasks and communication. Understanding parenting tasks and communication could assist pediatric nurses in supporting families and optimizing child outcomes (Fussel et al., 2011; Kitzman et al., 2010; Olds et al., 2004). In addition, filling these gaps in the literature provides a foundation for theoretically grounded, evidence-based work with families. Thus, the goal of this integrative review is to enrich and expand the current conceptualization of the tasks and communication involved in parenting young children based on the evidence from the literature. The focus is on children 0-5 years of age because the nature of both tasks and communication are linked to the child's developmental phase.

Framework

This integrative review is sensitized by two frameworks. First, Symbolic Interactionism informs this review because it focuses on how people create meaning as a way to comprehend their world (Blumer, 1969; White & Klein, 2007), including the role of socialization, which is a major goal of parenting. Second, Horowitz's “Critical Components and Characteristics of Effective Parenting” (1995) informs this review in that it specifically examined the process of parenting in various family structures.

Symbolic Interactionism (SI) fits the study of tasks and communication within the context of parenting. Three concepts foundational to SI and their relevance to parenting are presented in Table 1. Essentially, individuals assign meaning to persons, thoughts, ideologies, and objects based upon the value they hold for the person within the context of the person's own life and how other people interact with the person regarding them. This process of designating meaning is iterative, interpretive, reciprocal, and social. Parents socialize their children through the completion of tasks and when they communicate with them. SI posits that this process of socialization is highly reciprocal, in that parents and children influence one another and that both the parent and the child are active participants in the relationship (Blumer, 1969).

Table 1.

Foundational principals of Symbolic Interactionism and the application to parenting

| Precept of Symbolic Interactionism | Illustration in parenting |

|---|---|

| A person acts towards a thing based on the meaning a thing has for him/her. These things are all the things a person encounters in daily life (objects, people, feelings, concepts) (Blumer, p.2). | A new mother finds it difficult to perform childcare tasks for and communicate sensitively to her new baby after her husband announces he wants to end their marriage (shapes communication with baby and tasks of attending to baby's needs). |

| Meaning is “derived from or arises out of the social interactions” a person has with other people regarding a thing (as defined above) (Blumer, 1969, p. 2). | An exhausted mother feels better able to perform child care tasks for and communicate with her toddler after a trusted nurse practitioner points out and praises the benefits of a toddler's curiosity and energy to the exhausted mother, which helps the mother interpret the child's behavior and manage everyday childcare activities (shapes meaning child's behavior has for the mother and how she communicates with her child about it). |

| “Meanings are handled in and modified through an interpretive process used by the person in dealing with the things he encounters” (Blumer, 1969, p. 2). A person recognizes the meaning a thing has initially through a process of self-awareness or self-communication and then begins to interpret and shape these meanings as she/he considers this sense of meaning. This becomes a guidepost for how to act towards the thing. |

The meaning of a child becoming incontinent (“having an accident”) (“it is a big deal” or “it is not a big deal”) arises from the parent's own interpretation of the accident (“this is more work for me” or “these things happen”) in relationship with the child (“she is just bad” or “he is so engrossed in playing”)and this shapes the way in which the father cares for and communicates with the child after the accident (rough handling of the child and saying “you are bad” or normalizing the situation and saying, “It's ok. Let's change your clothes.”) |

The sharing of a complex array of common symbols (e.g. words, actions) allows children and their parents to adapt to new environments and roles. Even young infants who exhibit presymbolic or preintentional communication and parents who sensitively observe and respond to these actions participate in this complex exchange. The sharing of such symbols, and arriving at their agreed upon meaning, serve as a foundation for communication. Understanding the meaning inherent in parental tasks and communication for an individual (e.g. parent) is central to understanding the phenomenology of human behavior. Thus, examining the task and communication-related work of parenting through this lens can aid in understanding the meaning derived from parental work and how such meaning may influence parenting and ultimately the parent-child relationship.

Horowitz's (1995) “Critical Components and Characteristics of Effective Parenting” is unique because of its focus upon the normative actions involved in parenting including the tasks, roles, rules, relationships, communication, and resources involved in helping a child progress from one developmental level to the next, across family structures. The focus upon the normative actions of parenting can situate both expected and unexpected events experienced by parents across situation, time, and place (Belsky & deHaan, 2011; Gilliss & Knafl, 1999; McCubbin, 1999).

Definitions

In this review, parenting is defined as a complex social, cultural, and/or legally prescribed role that is directed towards caregiving for “...children from conception and birth through developmental challenges and life events to adulthood” (Horowitz, 1995, p. 43) and attending to their social, physical, psychological, emotional, and cognitive growth and development. In addition, parents are defined from a functional perspective as those individuals who identify themselves as the child's mother or father and provide consistent care to the child through various components of parenting. While this perspective has its limitations, this analysis is foundational and can be expanded based on other ways that families might organize to provide for children.

The preliminary definitions of parenting tasks and communication stem from Horowitz's (1995) original conceptualization of parenting. Parenting tasks are defined as, “activities parents do in managing the environment and maintain relationships among family members (Horowitz, 1995, p. 47). The particular activities vary across the age and developmental stage. Parenting communication is defined as the “...medium of exchange within families that occurs in three forms...verbal...non-verbal...and meta-communication” (Horowitz, 1995, p. 55). Please see Table 2 for a further description of tasks and communication.

Table 2.

Summary of study themes and implications for practice

| Parenting Tasks: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme | Definition | Findings | Implications |

| Parenting tasks are an avenue to self-efficacy and confidence (Barry et al, 2010; Benzies et al., 2008; Coleman et al., 2002; Davis et al., 2009; Fagan & Palkovitz, 2011; Leerkes & Burney, 2007) | Description of the ways in which parental tasks influence parents’ perception of their own competence in the parenting role | Maternal PSE predicted by her prenatal sense of self-efficacy; Paternal PSE predicted by involvement in childcare tasks and social support; PSE level influences satisfaction & stress in parenting role, as well as interactions with child | The work parents do in caring for their young child can improve their confidence in their ability, their perception of self-efficacy as a parent, and their connection to their child; nurses are in a position to provide anticipatory guidance and coaching |

| Parenting includes hands-on work, as well as the intangible work of behavior and emotion regulation (Cappa et al., 2011; Combs-Orme et al, 2002; Cipriano & Stifter, 2010; Lesane-Brown et al., 2010; Mirabile et al, 2009) | The actions and behaviors parents assume in caring for their children, including teaching the child how to respond appropriately to negative emotions or provocative situations | Infant care is described more than care of toddlers & preschoolers; parenting work needs to be examined through a contextualized lens (i.e. child developmental stage); findings demonstrate influence of child and parent upon one another | Nurses can understand parenting goals, beliefs, & behaviors by asking about this work; nurses can encourage parents to promote emotion regulation through direct coaching, role modeling, and understanding child's temperament well enough to alter the environment |

| Parenting includes distribution and allocation of child care work both inside and outside the family and influences role development (Barry et al., 2010; Cowdery & Knudson-Martin, 2005; DeCaro & Worthman, 2007; Ehrenberg et al., 2001; Milkie et al., 2010; Rose & Elicker, 2012) | How child care is carried out in the family, expectations maintained by family of who fulfills such roles, the work of finding/selecting parent extenders when both parents work outside the home, & how time is spent as a family | Traditional conceptualization of gender roles may not fit the needs of modern families; more discussion of shared parenting since 1995; less focus on fathers as providers of child care in family (versus mothers) | Doing child care tasks may create & enhance parent-child bond, therefore nurses can coach new and experienced parents in childcare tasks; nurses can ask both parents about how childcare is done in the family |

| Communication: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme | Definition | Findings | Implications |

| Crying and other non-verbal means of expression are powerful means of communication within the family (Zeifman, 2001; Catherine et al., 2008) | Describes the significance of information conveyed from one person to another through the act of crying and other non-verbal behavior | Crying and other non-verbal communication is important and powerful within a family; infants and young children communicate & influence the parent-child relationship from an early age | Nurses can help families become attuned to their child's cry and ask about their perceptions of crying; further conceptualization of crying will be helpful in areas of infant mental health & pain |

| Parents influence child development & behavior through communication (Barnett et al., 2012; Burchinal et al., 2008; Burnier et al., 2012; Camp et al., 2010; Garrett-Peters et al., 2008; Glascoe & Leew, 2010; Horowitz & Damato, 1999; Pesch et al., 2011) | Describes how parents exert a significant influence upon child development and behavior by the nature of & amount of communicating with them. | Optimal development is associated with talking to infant or child. Significance of talking in a responsive, sensitive manner not universally understood; positive socio-emotional outcomes from warm, responsive, & sensitive communication from parent to child | Nurses can assist parents in promoting their child's development through discussing the importance of & modeling warm interactions, even in the context of daily, mundane activities (e.g. getting dressed, shopping for groceries) |

| Parenting communication can be improved through methods to increase positive communication skills (Benzies et al., 2008; Gross et al., 2009; Horowitz et al., 2001; Horowitz et al., 2013; Lakes et al., 2011; Landry et al., 2006; Leitch, 1999; Scharfe, 2011) | Describes that optimal parenting communication is nurturing and responsive to the developmental stage and the needs of the child | Parenting communication can be influenced through various interventions that promote and teach positive parenting communication | Nurses can provide timely, relevant, experiential learning that teaches nurturing, responsive communication to strengthen parenting skills |

Methods

Whittemore's and Knafl's (2005) steps for integrative review were used to guide this analysis including: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation. Their method was chosen for this review because it calls for inclusion of diverse research methodologies in the analysis. This approach encourages a cross-disciplinary perspective on parenting and aids in the creation of a comprehensive model from which evidence-based clinical practice can grow.

The quality analysis guideline proposed by Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig (2007) was used to assess the qualitative articles and focused on participant-researcher relationship, how elements of qualitative rigor were maintained, and how analyses were undertaken. Quality analysis guidelines proposed by Long, Godfrey, Randall, Brettle, and Grant (2002; 2005) were used to assess the quantitative and mixed methods studies and focused on aspects of the research pertinent to a broad range of research designs and to evidence-based practice (e.g. generalizability to broader populations, policy implications, sample characteristics, intervention characteristics, statistical operations, and human subjects protections).

Literature Search Strategies

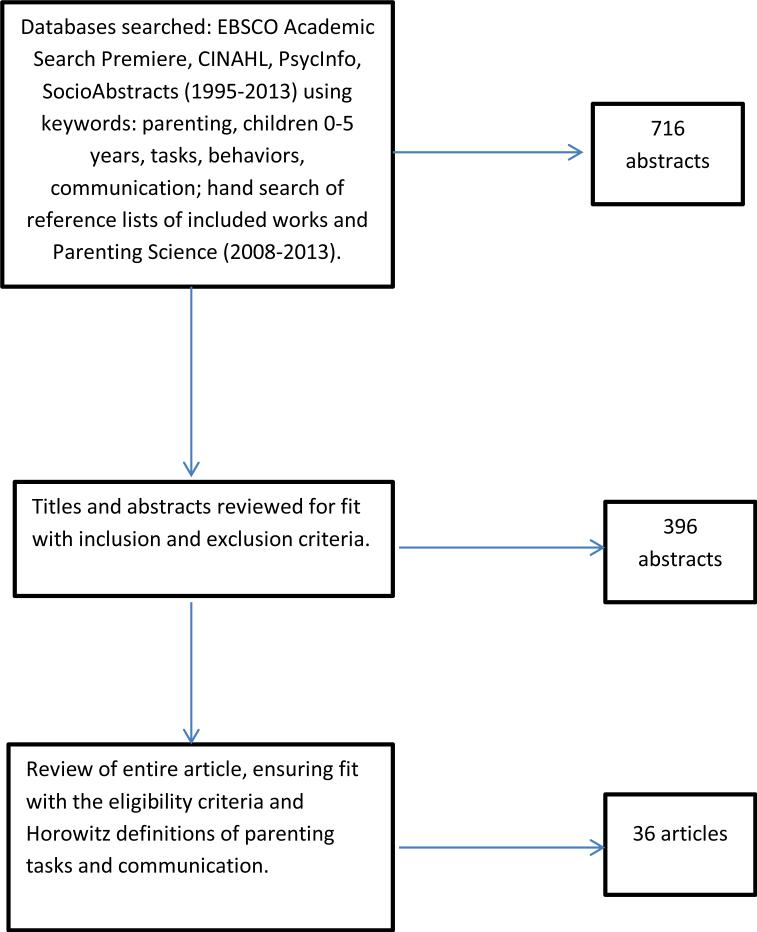

Figure 1 depicts the librarian-assisted literature search strategy, as well as the analysis strategy. Specifically, the first author searched four databases, reference lists of included articles, and Parenting Science (2008-2013) using the following key words: parenting, children 0-5 years old, tasks, behaviors, and communication. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria also guided the search and were used to ensure review of all relevant studies (Inclusion: published between 1995-2013; written in English, addressed human subjects’ protections; employed a research approach; focused on parenting or the parent-child relationship; conducted in North America; involved children 0-5 years of age; and, fit with Horowitz's definitions of parenting tasks and communication; Exclusion: published in a non-research format; not written in English; focused on the parenting of sick or disabled children or those in which a parent was disabled; focused on particular family structures or particular populations [e.g. those in which a grandmother is raising a grandchild, adolescent parents]; and those which focused on parenting in distress [e.g. child abuse and neglect]). These criteria narrowed the focus to core parenting processes that cross time, place, and space for varied populations.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of article selection criteria

Results

Thirty-eight articles fit the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis: twenty-six quantitative articles on tasks and communication, two qualitative articles on tasks, five mixed methodology articles, and five integrative review, critical review, or concept analysis articles on tasks and communication. No study is represented in more than one article. Please see Table 3 for a descriptive summary of methodological considerations for the articles included in the analysis. Overall, most articles employed quantitative methods, especially observation of parent and child in a naturalistic or laboratory setting. The majority of participants across studies were White, well-educated, middle-class mothers. In nine articles, the authors described equal distribution of African American, Latino(a)/Hispanic, and White participants in the study sample. Please see Table 4 for a description of all articles included in the analysis.

Table 3.

Summary of methodological considerations

Table 4.

Description of articles analyzed for integrative review

| Source | Participants | Design/Purpose | Key Finding | Strengths and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TASKS | ||||

| Theoretical | ||||

| Combs-Orme et al (2003) | Mothers & fathers | Concept analysis to review essential aspects of parenting an infant | Five classifications of parenting behavior: providing sustenance, supervision, safety, stimulation, structure, & support/affection; heuristic for parenting an infant; Supports necessity of understanding “contextual parenting” | Strengths: Grounded in and organized by conceptual model of “caregiving functions of parenting”; clearly present assumptions to the reader; contextualized description of parenting an infant Limitations: Limited discussion of how articles were chosen for the analysis and how analysis was conducted; no discussion of review's limitations |

| Gage et al (2006) | Mothers & fathers | Integrative review to synthesize and evaluate parenting research in nursing | Nursing research on parenting has primarily focused upon mothers and parenting children with disabilities; more precision needed in the language of parenting (How is it defined? Who acts as parents?) | Strengths: focus on nursing research to further understand gaps in research and opportunities for growth in research and practice; librarian-assisted search Limitations: Parenting not defined; definition or description of core journals that were searched for review not provided; no description of study quality |

| Fowles & Horowitz (2006) | Mothers | Critical review of observational & self-report instruments that measure components of mothering in clinical setting | 5 observational and 8 subjective report instruments that measure components of mothering (mother-infant interaction, gratification with the mothering role, & infant caretaking skills); Measures may be used clinically to identify high-risk mother child interactions and for research purposes | Strengths: grounded in Mercer's theory of Becoming a Mother; clear description of inclusion criteria of measures included in the analysis; reports on ease of instrument use in clinical setting Limitations: limited discussion of review limitations |

| Lutz et al (2009) | Parents and infants | Integrative review to evaluate and synthesize nursing research on parents’ perspectives on the parent-infant relationship | Themes related to healthy, term infants included parent child relationship as process, significance of helpful support, & interaction with and caring for baby as an avenue to facilitate the connection. | Strengths: Parental perceptions as a major focus of the review; listed theoretical foundations of analyzed works in summary table Limitations: study methodology and inclusion criteria were not explicitly explained in this paper, but in another paper in the series; focused specifically upon nursing research, so may have missed insights provided by other disciplines |

| Descriptive | ||||

| Cowdery & Knudson-Martin (2005) | 50 Mother & father dyads | Grounded theory to examine how gender equality is related to motherhood and how couples create equality | Two models of motherhood in which gender inequality may stem from mothers primarily completing childcare tasks and another in which fathers complete childcare tasks and collaborate with their partner | Strengths: sample was diverse in terms of gender, race, and social class; Some discussion of potential biases authors bring to analysis as wives, mothers, and feminist scholars Limitations: Limited discussion of study setting, participant recruitment, & data collection process; Discussion of analysis limited to derived themes |

| Davis et al (2009) | 56 two parent families recruited in third trimester of pregnancy | Longitudinal, observational study of relationship between infant temperament and co-parenting at 3.5 and 13 month Measures:CPS and ICQ |

Bidirectional relationship between infant temperament and co-parenting behavior; Father rating of early infant temperamental difficulty associated with decrease in supportive co-parenting behaviors over time; Infants play an early role in shaping the family system; Fathers more readily engage when they can be successful | Strengths: Longitudinal observation of child and family in both naturalistic and laboratory setting; recognition of the influence of infant upon parents; use of two different coders for observations of behavior Limitations: Sample consisted mostly of European American (85%), well-educated (93% mothers and 79% of fathers had obtained a college degree), middle-class (median income $51,000-60,000), and married (98%). |

| DeCaro & Worthman (2007) | Parents of pre-school children in 35 families; n=95 individuals | Daily life architecture and semi-structured interview to evaluate time use, daily scheduling, and work/family balance | Parents see themselves as providing child security, enrichment, and constant supervision, while minimizing overload; Mother (employed and not employed) and child schedule density correlated; Weekend time used to re-establish egalitarian parenting, with heavy Dad involvement in those activities | Strengths: Use of novel methodology to prospectively capture daily experience in families; gender diversity in sample (35 mothers, 25 fathers) Limitations: Sample consisted mostly of European American (74/95 or 78%), middle class (median income $70,000), well-educated (49/60 or 82% completed college or graduate school), married/heterosexual (25/35 or 71%) |

| Ehrenberg et al (2001) | 58 employed couples; Blended and step-families excluded | Mixed method interview and survey on “shared parenting,” marital satisfaction, and division of childhood tasks Measures: PTQ, KMSS, CCCT |

Spousal support most predictive of partners’ feelings of parenting competence, closeness with children, and marital happiness; Division of childcare tasks not independent predictor of marital happiness; Most families agreed that the mother did more of the child care, but both partners flexible in distribution of tasks; Giving and receiving support seen as an important task in dual-earner homes | Strengths: Mixed methodology; use of reliable and valid instruments; participants given opportunity for interview in naturalistic or laboratory setting Limitations: Sample consisted of all White, well-educated (average years of education=15 years), upper middle class (average family income =$76,284 Canadian), married (98% of couples) families in which most parents worked in professional/white-collar positions |

| Schulze et al (2002) | 32 mothers of 8 month old infants living in US (CT) and 28 from Puerto Rico | Semi-structured interview on beliefs and practices around infant feeding, sleeping, and toileting to understand influence of cultural beliefs upon parenting practices | Mothers in Puerto Rico emphasized performing tasks without assistance, whereas mothers in mainland US emphasized child's “emotional autonomy” In terms of training child for new skills, mothers from Puerto Rico looked for signs of readiness in children, whereas US mothers looked for signs of interest |

Strengths: Almost equal representation of mothers from Puerto Rico; mixed methodology to allow for observation and in-depth description of mothers’ beliefs; assessment of acculturation with PAS; interviewed in naturalistic setting Limitations: All participants self-selected and had some college education and lived in middle class homes in which the head of household worked in white-collar or professional work; limited discussion on measures to promote qualitative rigor |

| Milkie et al (2010) | 933 mothers & fathers | Secondary data analysis of 2000 National Parent survey to elucidate relationship among time with child, child well-being, and parents’ perceived work-family balance | Number of hours worked negatively associated with perception of work/family balance, time spent in routine child care negatively associated with perception of work-life balance, but time spent in quality activities with children positively associated with perception of work/life balance, task of parenting includes deciding how time will be spent; perception of parenting tasks influence beliefs about work/life balance | Strengths: Nationally representative, large sample; diversity in gender (fathers as almost 50% of sample) and educational background Limitations: Sample consisted of mostly White (76%), married (76%) parents; youngest child in the family was focal child of the survey, therefore cannot capture parent satisfaction in time spent with all children and dynamics of dividing time among siblings in a family; did not examine other parental factors that may influence satisfaction with work-life balance, like kind of work or mental health status |

| Rose & Elicker (2012) | 345 employed mothers | Survey to examine demographics, role beliefs, and choice of childcare providers | Child care preference depended upon child age, with most mothers preferring parental care for infants (87%) and center-based care for preschoolers (53%); mothers first choice of child care may not match the options available to them | Strengths: Implications for public policy discussed at length Limitations: Sample consisted mostly of White (79%), well-educated (63.4% with college or graduate degree), married (82%) mothers. Researchers developed the survey instrument-limited discussion of how validity was ensured |

| Empirical | ||||

| Barry et al (2011) | 152 employed mothers and fathers | Secondary longitudinal analysis of involvement and perceived skill of first-time fathers Measures: CES-D, CCT, GK, SCCT, Mother breastfeeding at 1 month, Mother work in hours at 1 year, father beliefs about crying response |

Fathers rated themselves as unskilled prenatally, but felt increasingly skilled over time post-natally. Involvement with child increased from 1 month of age to 1 year of age Fathers became more skilled when involved in child care early on, especially in those men who believed in being responsive and receptive to infant cues. Father's child care work influenced the relationship between mother's working and his beliefs in his skills Promoting self-efficacy and confidence in fathers can benefit the entire family |

Strengths: equal representation of fathers; focus on paternal growth in fathering role; use of several well-validated instruments; representation of families from lower middle class (median father annual income: $30, 214) Limitations: Sample consisted of mostly White (90% fathers; 94.7% mothers), married (77.6%) couples. Most had some college education (52.6% fathers; 50% mothers) |

| Cappa et al (2011) | 610 parents & their pre-school children | Longitudinal analysis of parenting stress and child coping Measures: ECBI, CCS, PSI-SF |

Bidirectional relationship between parent and child; parenting stress predicted later child coping competence and child coping competence predicted later parental stress across three time points | Strengths: use of well-validated instruments; longitudinal study design; recognition of bidirectional nature of parent-child relationship Limitations: Limited gender diversity (93% mothers) and sample well-educated overall (64% having completed some college or obtained a college degree) |

| Cipriano & Stifter (2010) | Parents & their children at 2 (n=126) and 4.5 years (n=72) | Observational study on maternal behavior and emotional tone and toddler temperament pre-school effortful control; Measures: CBQ; OCTS; PPVT | Due to differences in temperament, children vary in how they react to caregiver influence; preschoolers in this sample demonstrated higher effortful control when parents delivered redirection and reasoning to stop poor behavior in a positive tone | Strengths: Longitudinal study design; assessed behavior with both parents in family; use of several well-validated measures Limitations: Sample mostly White (92%), well educated (average 15 years of school for mother and 16 for father), middle class (average income 50-75,000) parents; only of White participants at final visit; observation in laboratory setting versus naturalistic setting; parents rarely used a negative emotional tone, so researchers unable to observe its effect on effortful control |

| Coleman et al (2002) | 68 mothers & their 19-25 month old children | Cross-sectional; observational study of maternal efficacy and competence and child development Measures: BSID; ICQ; SEPTI-TS, scaffolding |

Parenting behavior with negative impact=worse child development scores; Interaction marked by forceful redirection, ignoring misbehavior, pronounced expression of displeasure and anger in response to child's task-directed behavior. Positive impact parenting behavior marked by constructive assistance, emotional support, interest, efforts to corral misbehavior by mother | Strengths: Use of well-validated measures for child development, temperament, and parental self-efficacy; described coding schema in detail Limitations: Recruitment based on publishing of birth announcements in a local newspaper; Sample consisted mostly of white (66/68), middle class (average income 40-50, 000), well-educated (average 15 years of education) mothers; data collection and observation took place in university lab setting, not in a naturalistic setting |

| Fagan & Palkovitz (2011) | Sample of 1756 families grouped into 4 relationship styles | Longitudinal study on effect of co-parenting and relationship quality on father engagement with children across family structures Measures: co-parenting support; partner relationship quality; father engagement |

Residence & romantic involvement between parents are important contexts for father engagement with their young children in this study; Contextual factors are important when considering ways to engage fathers and children; Positive, co-parenting support helpful for dads and facilitated engagement with their children in romantic and non-romantic relationships with mothers | Strengths: Focus on fathers; longitudinal design; large sample; based on Fienberg's framework of co-parenting; larger study employed stratified random sampling across many cities; Psychometrically sound and reliable measures used in the larger study had been used previously (co-parenting support and parenting relationship quality) Limitations: Sample contained only men and families who have not experienced a relationship transition over study period (about 38% of the sample and grouped into 4 groups of mother-father pairs: married, co-habiting, non-residential romantic, non-residential non-romantic); did not look at father engagement across transitions in relationships |

| Mirabile et al (2009) | 55 mothers & their 2 year old children | Observational study of mother-child interaction to assess how child negative emotions are influenced by mother's regulatory and socialization strategies | Maternal efforts to teach distraction, redirecting influenced child ability to regulate frustration; Children were more likely to use negative strategies (i.e. venting, aggression) when same behavior done by the parent; Maternal verbal distraction positively correlated with child use of verbal distraction | Strengths: High response/participation rate; Sample included 84% African American mothers and 47% were head of household; observation done in a naturalistic setting Limitations: No discussion of what researchers would have done if they witnessed harsh or abusive parenting during the observation; tasks to elicit child emotional reactivity (2 minutes) and mother/child emotional regulation (5 minutes) may have been too short to elicit full reaction |

| Leerkes & Burney (2007) | 134 first time mothers and 90 fathers | Longitudinal study of development of parenting efficacy Measures: PBI, GSE, CES-D, IBQ, PSE, prenatal childcare experience, parenting satisfaction and social support, and child care activities |

The regression model proposed by the authors accounted for 40-56% of the variability in mother's and father's postnatal efficacy; strongest predictor of maternal postnatal efficacy was prenatal efficacy & perceived infant temperament; for fathers, postnatal efficacy predicted by his involvement in parenting tasks and the presence of social support | Strengths: inclusion of fathers and many also participated in phase II; used of well-validated, psychometrically-sound instruments; some representation of socioeconomic diversity Limitations: Sample consisted mostly of White (mothers: 77%; fathers: 86%); well-educated (mothers with college degree: 71%; some college: 19%. Fathers with college degree: 70%; some college: 23%), middle class (median income: $65,000, range $6-190,000), married/engaged couples, which potentially limits generalizability |

| Lesane-Brown et al (2010) | 18,827 families of kindergarten-aged children | Secondary data analysis from the ECLS to evaluate how often US families socialize their young children to their racial & ethnic heritage | Majority or minority status may influence teaching of racial/ethnic heritage: 60% of white families report never/almost never discussing racial/ethnic heritage with children; 34.5% of multiracial families discuss several times/month, 1/3 of American Indian families discuss several times/week, and 1/3 of Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders discuss several times/year; Socializing children to sociocultural history is part of the work of parenting | Strengths: Nationally representative sample gathered from original, longitudinal study; Large, diverse sample (60% White, 16% Black, 19% Hispanic, 3% Asian, multiracial 2%, American Indian 2%, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander 2%) Limitations: Limited information on sample other than race, ethnicity, parental level of education; No mention of who in family did reporting or who in family does the socializing conversations |

| COMMUNICATION | ||||

| Theoretical | ||||

| Zeifman (2001) | Infants and their parents | Integrative Review to examine the causes, impact upon survival, and evolutionary history of infant crying | The main function of crying is to promote parental caregiving; some Western caregiving practices (such as infrequent feeding and limited holding) may promote more crying; crying conveys information about the infant condition and guides decisions about what care to provide | Strengths: multi-disciplinary review (cultural anthropology, pediatric medicine, developmental psychology, physiology, and neurology); guided by a theoretical model (Tinbergen's ethology of behavior) and discusses crying over the course of child development and clinical applications Limitations: limited discussion of how literature was searched and analyzed or inclusion/exclusion criteria used to choose studies for review |

| Descriptive | ||||

| Burchinal et al (2008) | 1292 randomly selected families followed child's first 15 months as part of Family Life Project | Longitudinal observations and interviews on relationship between risk exposure in early infancy (<6months) and parenting/cognitive development | Severity of risk exposure negatively related to parenting and child development for infants as young as 15 months; higher risk in the contextual environment can lead worse parenting and child outcomes; influencing this path by decreasing risk in environment can change parenting and influence child cognitive skills; provides evidence for a pathway from risk severity to parenting to child outcomes; suggests initial parenting skills and their evolution during infancy predict cognitive skills | Strengths: grounded in cumulative risk model; longitudinal observations set in participant's natural environment; inclusion of rural population; large sample size through stratified, randomized sampling for a representative sample; discussion of the history of the geographical areas under study; assessed maternal literacy to screen for women who needed help with survey completion Limitations: limited information provided on training of interviewers and coders; no discussion of how understanding of cultural norms of parenting influenced analysis or how potential bias was prevented |

| Catherine et al (2008) | 49 different popular parenting magazines from Canada | Quantitative review on whether advice on colic and crying in popular parenting magazines reflect current evidence-based knowledge | Limited agreement in the popular literature regarding the causes of and responses to infant crying/colic; Over 100 causes of crying/colic with over 200 solutions found; limited discussion of abuse resulting from excessive crying/colic; gap exists between the advice offered in popular media and the evidence | Strengths: Examined the popular literature to understand what parents may be reading; large sample of magazines analyzed Limitations: limited discussion of how to bridge gap between evidence-based information and what journalists share with readership or health-care provider role in journalism. Limited discussion of other sources of information where parents learn about infant crying |

| Garrett-Peters et al (2008) | 1111 mothers and infants at 2 and 7 months of age | Longitudinal observations and surveys to evaluate contextual, child, and mother factors that influence emotion talk with infants Measures used: EARS, IBQ-R-2, KIDI, video of mother-child interactions, free play, and picture book task |

Maternal characteristics and social factors were predictive of her positive or negative emotion talk to child Child characteristics not as influential in predicting positive or negative emotion talk Underscores necessity of supporting mother in order to influence her communication with child |

Strengths: developmental epidemiological design employed to recruit representative sample; large sample obtained from an ethnically and geographically diverse communities of low-income families representative of six US counties (40% African American; 48% married) interviews conducted in naturalistic setting; used psychometrically-sound quantitative measures; use of two coders to analyze parent-child interactions and brief description of their training provided; high inter-rater reliability between coders Limitations: Limited consideration of wider context in which participant mothers live; ethnicity determined by biological criteria versus sociocultural considerations; limited gender diversity or consideration of father's influence upon emotion talk; no discussion of training and debriefing of research assistants who did home visits |

| Empirical | ||||

| Barnett et al (2012) | Mothers & children at 12, 24, & 36 months of age. | Observational, longitudinal study of link between mothers’ sensitive parenting and child's language skills & social competence at 36 months. | For boys, receptive language at 24 months contributes to greater sensitive parenting in mothers during 24-36 months of age; Significant main effect for influence of sensitive parenting on language skills for both boys and girls; Mother's sensitive parenting influenced by child's receptive language ability in toddlers/pre-school; shows how child can shape parenting | Strengths: rooted in transactional model of child development; longitudinal design; Sample: 44% African American and 56% European American; training of coders described; use of psychometrically-sound and well-validated measures Limitations: training of research assistants for preschool language assessment not described; no discussion of inter-rater reliability for research assistants assessing language; all observations conducted in laboratory setting |

| Burnier et al (2012) | 1549 4 year old Canadian children & their families part of the larger QLSCD | Cross-sectional survey and 24 hour dietary recall to examine relationship between mealtime arguments and child's daily energy intake | Eating environment may influence daily energy intake in preschoolers; mealtime free of arguments associated with increased energy intake versus children consistently exposed to arguments between parents and/or children; children never exposed to arguments at mealtime were twice as likely to consume more calories versus children often or almost always exposed, controlling for child activity level, television viewing while eating, maternal education, and presence of overweight parents; family communication influences food/calorie consumption; more fighting, less intake; parenting communication influences behaviors | Strengths: large, representative, population-based cohort of randomly-selected children born throughout the year in each province of Quebec; trained nutritionists conducted survey interviews in home (and in child care center for applicable); 24 recall administered evenly across all 7 days of week; survey items pre-tested on 150 parents of 4 year old children not participating in the study; diverse representation across socioeconomic groups: annual home income less than $20,000: 10%; $20-60,000: almost 47%; >$60,000: 42%; broad representation of maternal education: no high school: 15.8%; high school: 22.4%; college: 35%; university: 35%; High response rate: 88%; limited missing data Limitations: racial, ethnic, gender composition of sample not reported; sample mostly married (85%); dietary recall subject to underreporting on energy intake and snacking behavior; potential for underreporting argument behavior; reliability and validity of survey items not examined |

| Camp et al (2010) | 157 mothers & fathers of healthy 10-18 month old children | Secondary analysis of longitudinal RCT to examine relationship between characteristics of child's cognitive environment at 10-18 months and vocabulary at 18-30 months Measures used: StimQ, MCDI |

77% of the children with low parental verbal responsiveness scores at baseline had follow-up scores lower than the 25th percentile, (likelihood ratio: 4.3); 35% of the children with low parental verbal responsiveness scored less than the 25th percentile at follow-up; StimQ is clinically helpful for evaluating early environmental factors that affect vocabulary development; PVR may be most predictive of later vocabulary delay and can help identify children needing more support; Parents shape the child's cognitive environment and this influences cognitive development | Strengths: Sample diverse in terms of gender (male: 41.7%; female 58.3%); race/ethnicity: (African American: 17.8%, White: 24.2%, Hispanic: 38.9%, other: 19.1%); marital status (single: 33.1%; married or living together: 64.9%. Broad representation of low-income families (Medicaid/state child health plan insurance: 71.4%); broad representation of Spanish-speaking families (Spanish only: 7%; Spanish and English: 27.4%); longitudinal study design; use of validated measures Limitations: No description of research assistant training; potential for introduction of bias through the use of two different measures to assess vocabulary (infant form and toddler form); reports from families speaking only Spanish not included in analysis; limited discussion of study limitations |

| Glascoe & Leew (2010) | Mothers & fathers of 2-24 month old children enrolled in a larger study of the BITS and BPCIS | Cross-sectional, observational study to assess which behaviors, perceptions, and risk factors were associated with optimal or delayed child development Measures: BITS; BPCIS |

Four parenting behaviors predicted optimal developmental outcomes: helping child learn by talking to and showing child new things; talking to child in a special way; ability to make child feel better when upset; talking with child when feeding or eating with child; in families where book reading is uncommon, children twice as likely to have a developmental delay; negative developmental outcomes when parents did not report having fun with child or being able to engage child; parents who described fewer positive parenting behaviors or more negative behaviors had higher rates of developmental delay | Strengths: Sample was diverse in terms of race (White: 70%; Black: 14%; Hispanic: 12% Other” 4%); parent level of education (median: 13 years; no high school degree obtained: 22.5%; college/post-secondary training: 31%); 17 states represented in sample; all materials translated into and available in Spanish; high concordance between parent and observer rating of book-sharing exercise; took amount of exposure participants had spent to site into account when rating observed parent-child interaction Limitations: No description of sample gender distribution; no description of how this sample was drawn from parent study; No discussion of what authors offered to those parents in which they uncovered depression or anxiety; no description of the training provided to health care professional volunteers who conducted the interview and observation; no discussion of study limitations |

| Lakes et al (2011) | 154 pre-school aged children and their parents with 15 control families | Longitudinal, evaluation study of CUIDAR intervention; Measures: PSA; SDQ score at immediately pre & post intervention & 1 year later; FU | Intervention was a 10 week parent training to decrease attention & behavior problems in preschoolers; significant positive change in 8/10 parenting behaviors tested, especially using transitional statements and planning ahead in both post-intervention and 1 year later follow-up; child SDQ scores demonstrated significant positive change in all SDQ subscales, showing less problematic behavior; parents can influence child behavior positively with more positive, thoughtful communication with child | Strengths: Longitudinal study design; community-based model; parents trained in child development, positive parenting skills; child care provided on-site, as well as meals for the family; classes held in local community centers at various times of day in English and Spanish; open to all parents of preschoolers residing in the county; focus on low-income population; overall high rate of participation Limitations: comparison group not used in all analyses due to high rate of missing data; potential for bias since parents self-referred to CUIDAR; due to funding agency requirements to offer CUIDAR to all interested families, could not use randomization, wait list, or control group to assess for inter-group difference |

| Pesch et al (2011) | 113 mothers of preschool aged children | Mixed method to identify styles of talking about food with children & association with child demographics Measures: semi-structured interview and demographic data |

Four narrative styles of how mothers talk with their children about food identified (easy-going, practical no-nonsense, disengaged, effortful no-nonsense, indulgent worry, and conflicted control) and membership related to maternal demographics (p<.001) and child weight status (p <.05); 60% of the children of mothers in the conflicted control group were obese | Strengths: Diversity in race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (45/133 African American with lower SES; 29 White with lower SES; 32 Hispanic with lower SES; 15 white with middle/upper SES income; 12 Asian with middle/upper class SES), geographic location (urban versus rural), sample had blend of obese parents and obese children; interviews conducted in English or Spanish, test-retest reliability; qualitative rigor described Limitations: small sample for looking at across-group differences; potential for loss of meaning during translation from Spanish to English; Only one group of children had the anthropomorphic data |

| Scharfe (2011) | Mothers & their children in Toronto aged 0-50 months | Intervention study to evaluate the influence of a popular community-based 10 week parent-child program in a non-clinical sample of mothers & children Measures: PSCS; RCS; WDQ |

Participating mothers reported significant positive change in their parenting efficacy over time (F value 3.75; p<0.05) and that their child developed a more secure attachment over time (time 3: 81% of children in program described as securely attached by their mothers versus 62% of children with families on wait-list [x2 3.73; p,0.05]); interventions to increase parenting child communication also increase sense of attachment and parental self-efficacy | Strengths: Community based, non-clinical sample of families; rooted in attachment theory; high response rate initially; replicated the findings of two previous studies with a larger sample and matched wait-list group; sufficient power to detect difference between groups at various times; intervention is cost-effective and time commitment required of families (1 hour once/week for 10 weeks) is reasonable Limitations: Sample mostly White (no precise count given), married (94%), well-educated (89% with at least college/university education) mothers; lost close to 50% of sample by third time point; no description of survey psychometrics; no description of research assistant training |

| Benzies et al (2008) | First- time fathers and infants from two Alberta cities | Intervention RCT to determine the benefit of a parenting education program aimed specifically his at fathers of infants | New fathers reported that their educational and practice needs are different than new mothers: they prefer 1:1 instruction; support groups seen as less helpful until child is 1 year; participants found the program helpful, liked the focus upon fathers, and were interested in more father-specific activities | Strengths: focus on fathers; use of psychometrically sound instrument; sample diverse in terms of father educational level (54% college or university graduate); naturalistic setting; one nurse per family to build relationship; extensive training of research assistants/interventionists Limitations: Limited racial/ethnic diversity (85% European Canadian); fathers not screened for paternal depression |

| Leitch (1999) | 29 first-time mothers & their babies | Observational, intervention study of prenatal education and effect on quality of mother-baby communication during the first day of life Measures: NCATS |

Intervention group demonstrated more sensitivity to infant's cues and demonstrated behavior that supports socio-emotional development; intervention promoted higher-quality interaction between mother and baby | Strengths: Participants randomized to control or intervention groups; psychometrically sound instrument Limitations: No information on sample ethnicity provided; significant attrition (6/35 dyads did not complete the intervention); no discussion of study limitations |

| Landry et al (2006) | 264 mothers and their 6-10 months old infants (healthy subset) | Observational, intervention study of training on infant communication on maternal responsiveness and child development | Mothers who received the intervention were more responsive to the infant's cues and began to see these positive and negative cues as communication; mothers in intervention group more likely to demonstrate responsive communication to infant and these infants showed greater strides in social, emotional, and cognitive competence | Strengths: Sample diverse in terms of race/ethnicity (near equal representation of African American, White, Hispanic mothers) and focused on mothers from lower SES; low attrition rate (9%); key aspect of intervention was facilitator coaching mother in positive behaviors and notation of infant response to mother Limitations: high attrition rate for African American families versus White and Hispanic families; observations done in laboratory setting |

| Huang et al (2005) | 378 mother-infant dyads at 2-4 months & again at 16-18 months | Longitudinal, observational study to examine maternal child development training and later quality of parenting behaviors Measures: KIDI at 2-4 months; videotaped in interaction with child at 16-18 months (HOME; P/CIS; NCAST) |

No significant, direct effect of mother's correct estimation of child's development upon high-quality parenting behaviors; conversely, maternal underestimation of child's development during teaching tasks associated with lower- quality parenting behaviors | Strengths: rooted in developmental psychology and cognitive behavioral theory; longitudinal study design; sample diverse in terms of race (white: 61.9%; African American: 24.6%; Hispanic: 12.7%), maternal education,(less than high school: 14.3%; high school/GED: 33.1 %; some college: 32.8%; college or more: 19.6%) and marital status (married: 66.7%; single: 31.8%); used well-known, valid instruments; multiple, hierarchical regression analysis for control of confounding variables Limitations: no description of how interviewers were trained or how they were guided to respond to any child mistreatment in the home; validity of the NCAST not examined across racial and ethnic groups, therefore it may not fully capture how sensitive parenting is enacted across various groups |

| Horowitz & Damato (1999) | 95 post-partum mothers seen at 6 week post-partum obstetric visit | Cross-sectional, mixed-methods study to examine maternal perception of post-partum stress and satisfaction Measures: MIT,WPL-R, BSI-GSI |

Qualitative data revealed aspects of mothering that were both stressful and satisfying, including roles, tasks, relationships, and resources; quantitative data revealed that mean GSI scores for this sample was higher than expected for general population not seeking mental health care; WPL-R revealed that the sample generally had a high level of parenting satisfaction | Strengths: Sample diverse in terms of race and ethnicity (African American: 44%; White: 39%; Asian: 7%; Hispanic: 9%; Native American: 1%), mother's age (range: 16-43); parity (first time mothers: 55%), and income (<20,000: 30%; 20-39,000: 23%; 40-59,000: 24%; >60,000: 23%); mixed methods study design; recruited from obstetric office in a large, urban HMO Limitations: office setting for data collection may limit what/how much mothers share; cross-sectional design |

| Horowitz et al (2001) | Post-partum mothers and their infants | Longitudinal intervention study of the effect of a nurse-led coaching intervention to promote mother-child responsiveness Measures: EPDS, BDI, DMC |

All participants received 3 home visits and video-taping of mother-infant interaction, while intervention group also received coaching; participants in the intervention group had higher rates of mother-child responsiveness at time 2 and time 3 versus control group | Strengths: experimental, longitudinal design with randomization of sample; rooted in three conceptual frameworks; broad SES representation (<$50,000: 29%; >$100,000: 29%); research assistant coder blind to randomization assignment; low attrition rate Limitations: Participants mostly European American (68.9%), as opposed to African American (7.4%); Latina/Hispanic (7.4%); Mixed (7.4%); Other (4%); Asian (3.3%); Native American (1.6%); limited description of RA training |

| Gross et al (2009) | 253 2-4 year old children from day-care centers and their parents | Intervention, RCT to assess the efficacy of the Chicago Parenting Program (CPP) Measures: TCQ, PQ, DPCIS-R, ECBI, observation of child behavior |

Parents who participated at least 50% of the time saw positive effects, including increased PSE, warmth, consistency and decreased child misbehavior; at 1 year post-intervention, intervention group reported less corporal punishment and use of commands and more improved child behavior | Strengths: parent advisory board (comprised of African American and Latino parents) helped create program; wait list control day care groups matched to intervention group; day care centers randomized to control of intervention groups; Sample: 58.9% African American, 32.8% Latino; mostly single (intervention: 66.7%; control: 66.2%); most completed high school or some college (intervention: 50.7%; control: 61%); extensive training of RAs and group facilitators; free child care/dinner provided for intervention families Limitations: Limited gender diversity (mothers, intervention: 91.8%; mothers: control: 85.5%); only English speaking parents; low attendance rates for intervention (74/135 attended 5 or fewer sessions) |

| Horowitz et al (2013) | 134 Mothers recruited from two large academic medical centers in Northeastern US city and their infants | Intervention, RCT to assess efficacy of Communicating and Relating Effectively (CARE) intervention Measures: MIT, EDPS, DI with APRN; NCATS |

Little difference noted between groups due to CARE intervention-attributed to positive benefit from nurse visit in general versus CARE intervention alone; mothers in phase III focus groups and individual interviews (both control and intervention groups) reported significance of nurse visitation to their post-partum experience; Largest changes seen in both groups from 6 week visit to 9 month visit supporting positive benefit from nurse visitation, support, role modeling, and guidance that both groups received | Strengths: longitudinal design; random assignment to intervention or control; adequate power to assess for differences between groups/over time; most dyads retained throughout 9 month study protocol; rooted in theories of post-partum depression and cognitive behavioral therapy; use of well-validated instruments; broad racial/ethnic diversity (African American: 12%; Asian: 8%; Caucasian: 54%; Hispanic: 22%, other: 5%); Diversity in marital status (Married: 75%; single: 23%; other: 2%); intervention conducted in naturalistic setting of participants’ choice Limitations: Same nurse conducted intervention and control visits; while the sample was representative of the study geographic area, may not be representative of post-partum mothers nationally |

Note: BSID= Bayley Scales of Infant Development; BSI= Brief Symptom Inventory; BITS= Brigance Infant and Toddler Screens; BPCIS= Brigance Parent-Child Interaction Scale; CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression; DI= Diagnostic interview with Advanced Practice Nurse; EARS= Early Attention to Reading System; EPDS= Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; ELCS= Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey (Kindergarten-98-99); GSE= Global Self-Esteem; HOME= Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment Inventory, Infant/Toddler version; IBQ= Infant Behavior Questionnaire; ICQ= Infant Characteristics Questionnaire; KIDI= Knowledge of Infant Development Inventory; MCDI=MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory-Short Form; MIT=Mother's Information Tool; NCAST=Nursing Child Assessment by Satellite Training; NCATS=Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale; PBI=Parental bonding instrument-care subscale; P/CIS=Parent/Child Interaction Survey; PES=Parenting Efficacy Scale; PSCS=Parenting Sense of Competence survey; QLSCD=Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development; RCT=randomized controlled trial; RSQ=Relationship Scales Questionnaire; SEPT-TS=Self-Efficacy for Parenting Tasks-Toddler Scale; StimQ=subscales (reading, parental involvement in developmental activities, and parental verbal responsivity); WDAQ=Waters and Deane Attachment Q-sort; WPL-R=What being the Parent of a Baby is Like

Themes

Task-oriented themes

Six theoretical and empirical themes emerged from analysis of the existing literature: three from the task-oriented literature and three from the communication-oriented literature (Table 2). Each theme will be described from the collective literature and then a specific supporting example from the literature will be explained. The first task-oriented theme is that parenting tasks are an avenue to parental self-efficacy (PSE) and confidence, which is a description of the way in which parental tasks influence parents’ perceptions of their own competence in the parenting role. The work parents do in caring for their young child can improve their confidence in their ability to parent, their perception of self-efficacy as a parent, and their connection to their child. While mothers’ PSE was shaped also by their previous experience with young children (Leerkes & Burney, 2007), the authors of several articles described how fathers’ PSE and confidence were influenced by doing the work of parenting tasks (Barry, Smith, Deutsch, Perry-Jenkins, 2011; Benzies, Magill-Evans, Harrison, MacPhail, and Kimak, 2008; Davis, Schoppe-Sullivan, Manglesdorf, and Brown, 2009; Fagan & Palkovitz, 2011). This influence is exemplified by the following quote, “...that father involvement in child-care tasks was a strong predictor of father efficacy at 6 months suggests that practicing parenting increases feelings of efficacy...” (Leerkes & Burney, 2007, p. 62). This finding demonstrates that when fathers participated in the daily work of caring for their infants, they became more confident in their ability to parent and developed increased parental self-efficacy.

The second task-oriented theme is that parenting includes hands-on work, as well as the intangible work of behavior and emotion regulation. This theme encompasses the actions and behaviors that parents assume in caring for their children and includes teaching the child how to respond appropriately to negative emotions or provocative situations. One examples of this theme is work by Mirabile, Scaramella, Sohr-Preston, and Robinson (2009) in which the authors found that mothers can teach positive or negative emotion regulation when they model such behavior. In addition, Cappa, Begle, Conger, Dumas, and Conger (2011) described the bidirectional relationship between parental stress and child competence in coping with stressful situations, noting higher parental stress was related to lower child coping competence.

The third task-oriented theme is that parenting includes distribution and allocation of child care work, both inside and outside the family, and influences role development. This theme includes how families carry out child care work, how expectations of who does the child care work are maintained, and how families do the work of finding/selecting parent extenders (childcare providers when both parents work outside the home). (Cowdery & Knudson-Martin, 2006; Rose & Ellicker, 2012). In addition, the manner in which time is spent as a family-especially within the context of work-family balance and inclusion of children's activities is important (DeCaro & Worthman, 2007; Milkie, Kendig, Nomaguchi, & Denny, 2010).

Communication-oriented themes

The three communication themes (see Table 4) center on the impact of communication within the parent-young child relationship. The first communication- oriented theme is that parents influence child development and behavior through communication and interaction. This theme describes how the nature of and amount of parent-child communication can have a positive or negative impact on child development and behavior. As Glascoe and Leew (2010) noted, “Findings underscore the importance of early development promotion with parents, focusing on their talking, playing, and reading with children, and the need for interventions regarding psychosocial risk factors” (pg. 313).

The second communication-oriented theme is that crying and other non-verbal means of expression are powerful means of communication within the family. This theme underscores the significance of information conveyed from one person to another through the act of crying and other non-verbal behavior. Interestingly, this theme highlights the ability of infants and young children to communicate and influence the parent-child relationship from an early age. This theme also supports the significance of parental observation and attention to infant cues and sensitive response to this presymbolic communication, which serves as a foundation for the parent-child connection. The value of presymbolic communication of infancy and sensitive parent observation and response as the foundation for parent-child attachment is supported by this theme. Parent-child communication is certainly a reciprocal process that begins during pregnancy and becomes more explicit and multi-faceted beginning at birth. Moreover, communication becomes more nuanced and complex over time as parent and child develop and the relationship unfolds. The significance of crying as communication is noted by Zeifman (2001), “...in addition to serving to alert a mother of an infant's need for her attention in a general way, crying communicates information about an infant's state, health, and identity which influences maternal [parental] response” (p. 270).

The third communication-oriented theme is that parenting communication can be improved through methods to increase positive communication skills. The studies that support this theme offer a description of optimal parenting communication that is nurturing and responsive to the developmental stage and the needs of the child. This kind of communication and interaction with children can be influenced by interventions that promote and teach positive parenting skills, such as reading and responding to infant cues (Horowitz et al., 2001; Horowitz et al., 2013; Landry, Smith, & Swank, 2006; Leitch, 1999), reading and singing to children (Scharfe, 2011), and responding to misbehavior with sensitivity and consistency (Gross et al., 2009; Lakes, Vargas, Riggs, Schmidt, & Baird, 2011). In addition, parents also experienced positive effects through participating in several of the interventions (Benzies et al., 2008; Gross et al., 2009; Horowitz et al, 2001; Horowitz et al, 2013; Scharfe, 2011). Finally, an important methodological element of several interventions studies is the offering of a service tailored to both the interests of a community (Gross et al., 2009; Scharfe, 2011) and to the context in which community members live (Gross et al., 2009; Lakes et al., 2011).

Meta-themes

The themes were distilled into two meta-themes which can be incorporated into clinical practice:

Parenting tasks incorporate child care work, parenting roles, and outcomes for both the parent and child, and

Communication within a family context among children and parents is a reciprocal, symbolic process based upon both parent and child development in which family members influence each other and are influenced both immediately and long-term.

Taken together, these meta-themes underscore the clinical and research significance of studying parents and children for individual, family, and public health.

Discussion

In this review, the findings of thirty-eight articles were synthesized in order to examine the evidence regarding the influence of parenting tasks and communication on young children and their parents. Parenting tasks and communication are critical elements of parenting, are supported by the current empirical evidence, and, as demonstrated by Horowitz (1995), remain powerful and pertinent aspects of parenting and family life.

The results of this review elaborate what is meant by tasks and communication by taking a renewed look at the science of parenting within normative context of everyday family life. The results are a reminder of the need to understand the normative work of parenting in order to encourage parents in their roles appropriately. Children thrive when they are supported by their parents as demonstrated in numerous studies (Barnett, Gustaffson, Deng, Mills-Koonce, & Cox, 2012; Barry et al., 2011; Burchinal, Vernon-Feagans, Cox, & Key Family Life Project Investigators, 2008; Camp, Cunningham, & Berman, 2010; Cappa et al., 2011; Coleman et al., 2002; Garrett-Peters, Mills-Koonce, Adkins, Vernon-Feagans, & Family Life Project Investigators, 2008; Glascoe and Leew, 2010; Horowitz and Damato, 1999; Mirabile et al., 2009). Families thrive when parents are supported by invested professionals (Benzies et al., 2008; Gross et al., 2009; Horowitz et al., 2001; Horowitz et al., 2013; Lakes et al., 2011; Landry et al., 2006; Leitch, 1999; Scharfe, 2011). This understanding may be necessary in order to elucidate parenting in non-normative situations (Gilliss & Knafl, 1999).

This review also draws attention to the need for assessment of parental development. Just as child growth and development are assessed over time to ensure health and growth, parental growth and adaptation over time should also be assessed. As early as the prenatal meeting or newborn exam, nurses can ask parents about their own developmental history since this may influence what a parent believes to be customary or normal parenting behavior (Super and Harkness, 1986) and may even influence potential risks the child could face developmentally (Tough, Siever, Benzies, Leew, & Johnston, 2010). A parental developmental assessment may be achieved by observing how parents carry out tasks of caring for their young children and how communication is done in a family. Nurses can also ask about parents’ goals of parenting. After a relationship is established with a parent, nurses could ask what has been challenging to deal with as the child develops, how the family has addressed the challenge, and how they would evaluate the response. Asking such questions allows the parent an opportunity to reflect and consider his or her actions without the emotion or distracting stimuli present during their interaction with the child. Anticipatory guidance can be based upon this assessment.

The newly derived meta-themes are based upon the research literature. They reflect the developmental and family contexts that influence parenting tasks and communication; the bidirectional, dynamic nature of the parent-child relationship; the effect of this relationship on parent and child; and the significance of assessing parental development. Consist with symbolic interactionism, the dynamic, symbolic, and reciprocal nature of parenting work is reflected in these meta-themes and draws attention to the manner in which parent and child learn about themselves through interaction with the other and the potential for meaning derived from this interaction.

Finally, the everyday deserves consideration. This review draws attention to the value of those tasks that may be perceived as mundane and the communication involved in such tasks. As noted in the communication themes, simple acts of talking to and reading with children in the context of everyday tasks, such as buying groceries or walking to the park, can have a profound effect of childhood outcomes. The articles that describe the communication interventions demonstrate how nurses can influence the daily lives of children by offering support the parent recognizes as valuable and contextualized. Parenting tasks are an avenue to improve communication and the quality of the parent-child interaction and serve as a method to help parents find meaning in the seemingly unending work of caring for young children.

This integrative review is shaped by several important limitations. First, analysis is hampered by the limitations of the studies included in the review, especially in terms of sampling. For example, nearly half of the studies in this review employed samples with a majority of white, well-educated, middle-class mothers. This limitation highlights the need for thoughtful recruitment and retention strategies. The articles with more diverse samples reported planned and targeted recruitment of less-represented groups or employed community-advisory boards to provide guidance to the study team. In addition, the intervention studies that targeted less-represented groups consistently demonstrated positive effects through most time points, pointing to the significance of constructing studies and interventions that are sensitive to the contextual realities of their participants. Second, this review was limited to research that came from North America. While there is great heterogeneity in North American parenting, this step was taken in order to gain a contextualized understanding of parenting. Consistent with Super and Harkness (1986), parents are influenced by the surrounding culture, which organizes parenting behaviors and impacts their beliefs about the nature and needs of children. Lastly, the review covered the years 1995 (the year of Horowitz's initial conceptualization)-2013, which may have limited access to other seminal works. While ancestral reviews of the included articles and of a journal specifically focused on parenting were conducted to adjust for this limitation, the review may not be exhaustive.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Optimizing family and child health outcomes is at the heart of pediatric nursing (Lutz, Anderson, Riesch, Pridham, Becker, 2009). To promote the best outcomes for children, however, parents and caregivers must also be the recipients of our attention (Bright Futures, 2008). Children are typically nested within a family and community; to divorce children from those broader influences is to address only part of the puzzle. Parenting discussions are within the realm of pediatric, mental health, and family nursing. In discussing parenting beliefs and practices, nurses can learn about family goals, the beliefs that drive parenting behaviors, and the source of such beliefs. Knowing this information, nurses can build on family strengths, support their positive beliefs, and assist the family in restructuring negative thoughts and beliefs in order to optimize the parent-child relationship (Goldenberg, Goldenberg, & Pelavin, 2011). Nurses are vital because they have sustained interaction with families across settings, including the home.

The findings of this review also provide a pathway for family-focused collaboration in the clinical setting (i.e. with physicians, clinical psychologists and social workers, physical/occupational therapists) and in the community (i.e. with school psychologists and nurses, early childhood and kindergarten teachers, and clergy). Frequently, families of young children desire to learn about the child, build on family strengths, and address opportunities for change. The results of this analysis demonstrate that nurses and other professionals can promote child and parent development and well-being, provided this support is relevant, timely, and sensitive to the context in which families live.

Family and parenting science scholarship is readily applicable to the many well-child visits that characterize the care of healthy young children. An assessment of not only child development, but also of parenting communication and management of tasks is essential. Examples of questions to guide this assessment are offered in Table 5. Anticipatory guidance can follow based on this assessment. By knowing that parenting work can also strengthen the parent-child relationship, nurses can draw attention to a child's reaction to a parenting behavior (i.e. by communicating, “See how the baby looks for you when he hears your voice”), especially with fathers, partners, and less-experienced mothers. Consideration of the parenting communication themes is a reminder to observe the totality of family communication, including verbal, non-verbal, and meta-communication, while modeling optimal communication with both parents and young children.

Table 5.

Questions to assess tasks and communication in the clinical encounter

| Tasks | Communication |

|---|---|

| 1. Who does what in terms of the hands on work of the child? (Probe for satisfaction with allocation of work if the parent has a partner, i.e. mutuality) 2. What do you believe are the most important things that you do for your child now? Has that changed over time? (Probe for both tangible and intangible work and emotional regulation) 3. How manageable is the work? (Probe for perceptions of competence or ability) |

1. How does your child tell you he/she needs something? How has that changed over time? What happens when your child cries? Who typically responds? How has that changed over time? 2. How does your child generally respond to your attempts to comfort him/her? 3. (As appropriate) Does your partner typically give you feedback about your parenting in front of your child? If so, what does he/she say or do? (probe for criticism or threatening non-verbal behavior) 4. What happens when your child does something that he/she is supposed to do? Not supposed to do? (Probe for verbal, non-verbal, and meta-communication). |

The many disciplines that interact with young children and their families need not reinvent the wheel: the reviews and cross-sectional works demonstrate that families have strengths on which invested professionals can build. Further, the intervention studies demonstrate how simple advice and behavior modification grounded in a family's reality, improved children's cognitive, social, and emotional outcomes. By reorienting parents to their children and by reframing the significance of tasks and communication as a way to bolster the parent-child relationship, nurses and other professionals can help families achieve their potential.

Implications for Clinical Research