Abstract

Relapse presents a significant problem for patients recovering from stimulant dependence. Here we examined the hypothesis that patterns of brain function obtained at an early stage of abstinence differentiates patients who later relapse versus those who remain abstinent. Forty‐five recently abstinent stimulant‐dependent patients were tested using a randomized event‐related functional MRI (ER‐fMRI) design that was developed in order to replicate a previous ERP study of relapse using a selective attention task, and were then monitored until 6 months of verified abstinence or stimulant use occurred. SPM revealed smaller absolute blood oxygen level‐dependent (BOLD) response amplitude in bilateral ventral posterior cingulate and right insular cortex in 23 patients positive for relapse to stimulant use compared with 22 who remained abstinent. ER‐fMRI, psychiatric, neuropsychological, demographic, personal and family history of drug use were compared in order to form predictive models. ER‐fMRI was found to predict abstinence with higher accuracy than any other single measure obtained in this study. Logistic regression using fMRI amplitude in right posterior cingulate and insular cortex predicted abstinence with 77.8% accuracy, which increased to 89.9% accuracy when history of mania was included. Using 10‐fold cross‐validation, Bayesian logistic regression and multilayer perceptron algorithms provided the highest accuracy of 84.4%. These results, combined with previous studies, suggest that the functional organization of paralimbic brain regions including ventral anterior and posterior cingulate and right insula are related to patients' ability to maintain abstinence. Novel therapies designed to target these paralimbic regions identified using ER‐fMRI may improve treatment outcome. Hum Brain Mapp 35:414–428, 2014. © 2012 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: cingulated, insula, cocaine, methamphetamine, drug dependence, attention

INTRODUCTION

Substance use disorders present tremendous health and social problems, affecting over 20 million Americans [Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010], with stimulant use being one of the most prevalent and costly. In 2008, over 6 million individuals in the U.S. reported past year cocaine or methamphetamine use [National Drug Threat Assessment, 2011]. Repeated drug use can result in dependence and addiction, leading to significant comorbid health problems. Current methods of treatment for stimulant dependence are effective for a time [Knapp et al., 2007], but relapse is common and presents a significant problem [Frawley and Smith, 1992]. Large individual differences are found across patients in the length of abstinence, ranging from a few days to years or the remainder of a lifetime. It would be useful to understand the factors associated with shorter versus longer durations of abstinence in order to develop more effective treatments for this disorder.

Few previous studies have applied neuroimaging techniques to study the individual differences related to treatment outcome, e.g. continued abstinence versus relapse to drug dependence. Most previous studies of relapse have focused on clinical, behavioral and demographic measures, along with demographic, health history, and family history of drug use, among other sources of data [Brecht et al., 2000]. One of the first studies to examine neuromarkers predicting relapse was Bauer 1997, who found that the amplitude of the frontal P300 or P3f ERP component evoked by stimuli in the three‐stimulus oddball attention task predicted subsequent relapse in patients recovering from cocaine dependence with an overall accuracy of approximately 63%. The findings of Bauer 1997 raised the question of which specific brain regions or networks of regions were associated with relapse. While ERPs offer excellent temporal resolution, their spatial resolution is limited by the high impedance of the skull, and the inverse solution that is underdetermined. Other methods, such as fMRI, provide superior spatial resolution, but offer limited temporal resolution, making it difficult to replicate rapid event‐related paradigms that are used in ERP studies. In order to identify the location of brain regions with hemodynamic responses evoked by the same stimuli that produce the P3f, we developed methods for employing rapid, randomized event‐related paradigms with fMRI, termed event‐related fMRI [ER‐fMRI; Clark, 2012]. We have also found that the addition of parametric modulation to the blood oxygen level‐dependent (BOLD) response model provides dramatically increased sensitivity for detecting BOLD activity evoked by the oddball task [Clark, 2002]. Using these methods in healthy subjects, we found the largest ER‐fMRI response to distractor stimuli presented in the three‐stimulus oddball task was located in bilateral orbitofrontal, ventromedial prefrontal, anterior cingulate, medial/inferior/superior frontal, parietal, cerebellar, and superior temporal regions. These regions partially overlapped with those previously found by Kosten et al. [2006] and Paulus et al. 2005 to differ based on relapse potential, including frontal and cingulate cortex.

In the present study, we examined the question of which brain regions or networks of regions differ in their activity before relapse occurs by focusing on the anatomical location of ER‐fMRI activity evoked by the same stimuli that evoke the P3f. We employed our previously developed ER‐fMRI methods to perform a prospective longitudinal study similar to Bauer 1997, in which we collected ER‐fMRI data at an early stage of abstinence, and then monitored these patients for relapse. Neuroimaging, behavioral, and clinical data obtained at intake were compared between patients who relapsed with those who remained abstinent, to identify which factors or collections of factors were most closely associated with a higher potential for relapse. We hypothesized that the superior anatomical resolution of ER‐fMRI, combined with advanced methods of modeling brain networks and associations between brain function and clinical outcome, would provide a more sensitive measure of relapse potential than ERPs, due to its ability to focus on the specific neural pathways involved in this response. We further hypothesized that a portion of the regions previously found to respond to distractor stimuli in healthy subjects would be altered in the comparison between relapsing and abstinent patients. We then compared our findings with other previous fMRI studies of relapse to stimulants [Kosten et al., 2006; Paulus et al., 2005] to infer the neural and cognitive mechanisms that are common among them.

METHODS

The University of New Mexico, Human Research Review Committee approved this study, and each patient gave informed consent before participating. Recently abstinent cocaine‐ and methamphetamine‐dependent patients were recruited from local treatment programs, 12‐step programs and other patient support groups, and newspaper advertisements, and were screened for inclusion in the study. Healthy controls were not included as there are many differences between nondependent and stimulant‐dependent populations, which would confound the subsequent analyses. Therefore, only data from stimulant‐dependent patients were included in this study. Screening was performed for availability for follow‐up testing, contraindications for fMRI, alcohol dependence, use of prescription drugs that could alter fMRI responses, poor perceptual ability, and serious psychiatric or other medical conditions. A total of 45 patients underwent complete intake interview and imaging sessions, and were subsequently monitored until 6 months of abstinence was achieved and verified, or relapse occurred. Additional patients were screened for whom only a subset of these data were obtained, in which imaging data were not obtained from some patients, and relapse data were not obtained from others. Data from these subjects will be reported separately.

Intake occurred at minimum of 1 week of abstinence, (with an average of 40.6 ± 4.94 days SEM) in order to allow initial withdrawal symptoms to subside. At intake, an extensive battery of self‐report demographic, substance use, treatment history, and motivation measures were administered. In addition, psychiatric history and substance use patterns were assessed using the computerized diagnostic interview schedule, version 4 [CDIS‐IV; Robins et al., 1995, 1981], as well as questions pertaining to quantity and frequency of all major categories of substance use in the 6 months before inclusion in the study. The use of medications in the past 6 months was also assessed. Specific variables were created to indicate the highest number of dependence symptoms for any drug of abuse in the past 6 months, the number of medications used in the past 6 months, the length of time since first regular drinking, the length of time since first use of all drugs of abuse, and the length of time since first use of psychomotor stimulant drugs. Potential patients were rejected who were dependent on any other drugs, including alcohol, within the past 6 months. However, a history of abuse for other drugs and current dependence on nicotine was allowed. The length of abstinence from stimulant drugs before baseline scanning, prior incidence of relapse to stimulant use, and the length of time to relapse (if applicable) were calculated. Lifetime consequences of substance use were examined using the Inventory of Drug Use Consequences [InDUC; Tonigan and Miller, 2002], motivation for change was examined using the Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale [SOCRATES; Miller and Tonigan, 1996], craving was examined using the Subjective Experience Questionnaire (SEQ), 12‐step program participation, and help seeking in the months before baseline including seeking help from a councilor, clergy, physician, psychiatrist, inpatient and/or outpatient treatment support, participation in recovery and drug‐free housing, and use of anticraving drugs were also assessed.

Demographic measures used in the study included age, gender, ethnicity, racial origin, years of education, and handedness. In addition, both paternal and maternal histories of alcoholism were measured through patients' assessment of their Father's and Mother's likely scores on the Michigan alcohol screening test [MAST, 13‐item version; Pokorny et al., 1972; Seizer et al., 1975]. Binary measures for paternal alcoholism were generated using a cutoff score of 5 on the 13‐item MAST test.

History of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, mania, psychosis, gambling, and childhood disorders (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), separation anxiety, and oppositional defiance disorder (ODD)), were assessed according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [4th ed., text rev.; DSM‐IV‐TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000] using the CDIS‐IV computerized interview format. Lifetime counts of medical, psychiatric, and substance abuse treatments, as well as past incarcerations, were also documented by means of interview. Current (past 7 days) self‐reported psychiatric symptoms were assessed using the SA‐45 (Maurish 1999] a composite scale of positive symptom totals that also contains nine subscales measuring anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive, somatization, panic anxiety, hostility, interpersonal sensitivity, paranoid ideation, and psychotic thought processes. Specific variables were created to indicate the total number of treatment episodes/incarcerations. Neuropsychological tests were performed to assess the functional consequences of any differences in BOLD imaging measures that were found. General cognitive functioning was assessed using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) IQ test. The trail making tests [Trails A and Trails B; Bowie and Harvey, 2006], verbal fluency test [FAS; Lezak, 1995], and the Wisconsin card sorting task [WCST; Berg 1948] were also administered. All individuals were randomly tested for drugs and alcohol before, during and after the imaging session, and during a 6‐month follow‐up period. Any positive screen resulted in immediate discharge from the study at intake, and a positive screen for stimulants resulted in discharge after imaging was performed.

Selective Attention Task

The three‐stimulus oddball task optimized for use with fMRI as been described in detail elsewhere [Clark et al., 2000, 2001; Clark, 2002]. Briefly, patients were required to recognize and respond to a single target letter while nontarget letters were presented in series. Individual runs were approximately 3 min in length, with 90 stimuli per run. Four runs were used, for a total of 14 min of data collection, with rest periods interspersed. Stimuli were a frequent, nontarget letter (“T,” 296 of the 360 total stimuli, or 82% of stimuli), a distractor letter (“C,” 32 or 9% of stimuli), and a target letter (“X,” 32 or 9% of stimuli). Patients were asked to respond with a single speeded button press response every time the target letter was presented. Stimuli were presented for 200 ms each, with an interstimulus interval (ISI) that varied randomly from 550 ms to 2,250 ms across trials. The oddball task was administered using E‐Prime (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA), and behavioral data were collected using Chart software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Behavioral analyses were performed using SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

fMRI Image Acquisition and Analysis

MRI data were acquired using a 1.5T Siemens Sonata Maestro system (Erlengan, Germany) with a circularly‐polarized head coil. Foam padding was used to minimize head movement. Before functional scans, localizing and magnetization‐prepared rapid acquisition with gradient echoes images were acquired to determine proper placement in the scanner and neuroanatomy. During task performance, whole‐brain T2*‐weighted dual‐echo, gradient echo echo‐planar functional images were acquired in 25 slices with a repetition time of 2,100 ms (thickness = 6 mm with a 0.3 mm gap, echo time = 19 ms and 48 ms, flip angle = 90 degrees, field of view = 256 mm, matrix = 64 × 64). Slices were oriented parallel to the orbitofrontal cortex to minimize susceptibility artifacts. Together with the use of the multiecho EPI acquisition, we were able to minimize the loss of signal resulting from susceptibility artifacts in orbitofrontal cortex.

A number of different analyses were performed to determine the degree to which brain activation at an early stage after cessation of drug use predicted relapse up to 6 months later. fMRI data were processed using the SPM5 software package (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience) running on Matlab (The Mathworks, Inc). Following slice‐timing correction, images were realigned using a motion correction algorithm unbiased by local signal changes [INRIalign; Freire et al., 2002]. Participants whose mean signal changes were greater than 2 standard deviations from the mean of their respective group were excluded from further analyses. No participants were found that had this large a deviation from the group mean of movement, so no participants were removed based on movement. Data were spatially normalized into the standard Montreal Neurological Institute space [Friston et al., 1995] using the “normalize” procedure in SPM by normalizing the EPI images to the SPM EPI template, which may limit resolution relative to normalization using structural images. Data were then spatially smoothed with a Gaussian kernel (full‐width at half‐maximum = 9 mm). We have previously found that the addition of parametric modulation to the BOLD response model provides dramatically increased sensitivity for detecting BOLD activity evoked by the oddball task [Clark, 2002]. Parametric modulation including first‐ through third‐order polynomial expansion was employed to independently model within‐patients BOLD fMRI signal changes across trials. This was done by replacing the input function for each stimulus with the appropriate value given the polynomial function being used for that regressor based on its ordinal position in the stimulus series for that stimulus type, which was then convolved with the hemodynamic response function before regression was performed. This resulted in four regressor per stimulus type, including one for the main effect of stimulus presentation (predicting the same response amplitude for each stimulus) and three polynomial functions (e.g. linear, quadratic, and cubic). Between‐groups comparisons for each polynomial regressor included voxel‐wise t‐tests with corrections for multiple comparisons (family wise error < 0.05). The second‐level group contrasts involved standard SPM5 procedures using random effects analysis. Group independence and heterogeneity of variance were assumed. Grand mean scaling was not employed. No covariates were entered into the contrast model. No threshold masking was used, global calculation was omitted, and no global normalization was employed. SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to contrast participant characteristics.

Follow‐Up Testing

Patients were tested weekly using urinalysis and breathalyzer, and once every 3 months using hair analysis (Psychemedics, Inc). Participants were followed until they had either reached 6 months of abstinence from their initial abstinence date for any stimulant use, or until relapse to stimulant use was verified. Relapse was deemed to have occurred if a participant tested positive for cocaine and/or methamphetamines in any of their urine drug screens or hair analyses, or if they admitted to use of either of these substances during their follow‐up period. Relapse versus abstinence was collected as a binary measure. Detailed descriptions of the severity of relapse were not obtained due to the difficulty of collecting detailed information on many patients who relapsed, and then would break contact with study personnel. Abstinence was deemed to have been continuous if a participant tested negative for these substances in all of their urine drug screens/hair analyses, and there were no collateral reports or of self‐reports of relapse to stimulant use. We found no instance of self‐reports of abstinence or relapse that were not corroborated by urine or hair testing, suggesting that the patients enrolled in this study were truthful in their reports.

RESULTS

During the follow‐up period, 23 of the 45 patients (51.1%) relapsed after a median of 81 days of abstinence (SEM 9.38). Of these, 12 were primarily cocaine‐dependent and 11 methamphetamine‐dependent. For the group of abstinent patients, 10 were primarily cocaine‐dependent and 12 methamphetamine‐dependent. There were no significant interactions between drug of choice and relapse status, suggesting that differences found between relapsing and abstinent groups were not directly related to drug of choice.

Sociodemographic, symptom, and use characteristics for the 6 months before inclusion in the study were examined to find variables that significantly differentiated those who relapsed during the follow‐up period versus those who did not (Table 1). Patients who relapsed had 2.13 more years of formal education (t = 4.415, P = 0.003 corrected for multiple comparisons) than patients who maintained abstinence. There were no significant differences in age, gender, or ethnicity between groups when corrected for multiple comparisons.

Table 1.

Characteristics of relapsing and abstinent patients

| Variable | Relapse (n = 23) | Abstinent (n = 22) | Test value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 36.8 (7.348) | 31.3 (7.887) | t (43) = 2.426 |

| Years of education | 12.1 (1.392) | 10.0 (1.826) | t (43) = 4.415a |

| Cognitive flexibility (WCST) | |||

| Nonperseverative errors | 42.4 (10.655) | 48.6 (10.186) | t (42) = −1.964 |

| Perseverative errors | 46.8 (12.135) | 56.8 (17.166) | t (35.666) = −2.218 |

| Categories completed | 4.8 (1.749) | 5.67 (0.658) | t (28.598) = −2.144 |

| Failure to maintain set | 1.6 (1.619) | 0.7 (0.902) | t (35.056) = 2.177 |

| General Cognitive Functioning (WASI) | |||

| Full scale IQ | 99.3 (10.508) | 95.4 (13.243) | t (42) = 1.097 |

| Verbal IQ | 97.8 (13.862) | 90.6 (12.023) | t (42) = 1.859 |

| Performance IQ | 101.0 (10.563) | 100.4 (15.716) | t (42) = 0.146 |

| Substance use (past 6 months) | |||

| Frequency of drug use | 2.68 (0.814) | 3.53 (1.201) | t (36.947) = −2.742 |

| No. different types of drugs used | 1.76 (0.409) | 2.20(0.524) | t (42) = −3.069 |

| Lifetime Psychiatric Comorbidity (CDIS‐IV) | |||

| Total CDIS‐IV diagnoses | 2.5 (2.212) | 1.5 (1.184) | t (33.958) = 2.029 |

| Posttraumatic stress (PTSD) | 10 | 4 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 3.357 |

| Active PTSD | 8 | 2 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 4.294 |

| Major depressive episode (MDE) | 13 | 8 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 1.836 |

| Active MDE | 0 | 0 | |

| Dysthymia (DYS) | 1 | 0 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 0.978 |

| Active DYS | 0 | 0 | |

| Manic episode (MAN) | 9 | 1 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 7.782 |

| Active MAN | 7 | 1 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 5.156 |

| Hypomanic episode (HYP) | 2 | 1 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 0.311 |

| Active HYP | 1 | 1 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 0.001 |

| Schizophrenia (SCZ) | 2 | 0 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 2.002 |

| Active SCZ | 2 | 0 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 2.002 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity (ADHD) | 6 | 3 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 1.089 |

| Active ADHD | 5 | 3 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 0.505 |

| Separation anxiety (SEP) | 4 | 3 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 0.121 |

| Active SEP | 0 | 0 | |

| Oppositional (OPP) | 11 | 11 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 0.021 |

| Active OPP | 2 | 5 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 1.685 |

| Pathological gambling (PGD) | 3 | 2 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 0.178 |

| Active PGD | 2 | 1 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 0.311 |

| Schizophreniform (SRD) | 3 | 1 | χ2 (1, N = 45) = 1.003 |

| Active SRD | 0 | 0 | |

| Current Psychiatric Distress (SA‐45) | |||

| Positive symptom total (PST) | 22.4 (11.488) | 15.2 (11.721) | t (43) = 2.084 |

| Anxiety (ANX) | 9.9 (4.420) | 7.5 (3.596) | t (43) = 2.004 |

| Depression (DEP) | 10.6 (4.736) | 8.8 (3.775) | t (43) = 1.398 |

| Obsession (OBS) | 11.8 (4.572) | 9.2 (3.948) | t (43) = 2.038 |

| Somatization (SOM) | 10.0 (4.200) | 8.7 (4.684) | t (43) = 0.995 |

| Panic (PAN) | 7.4 (2.675) | 6.5 (3.582) | t (43) = 0.997 |

| Hostility (HOS) | 6.4 (1.779) | 7.1 (4.291) | t (43) = 0.722 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity (INT) | 8.8 (3.789) | 7.9 (4.015) | t (43) = 0.790 |

| Paranoid ideation (PAR) | 9.0 (2.763) | 8.1 (3.443) | t (43) = 1.028 |

| Psychoticism (PSY) | 6.9 (2.117) | 6.2 (2.975) | t (43) = 0.837 |

| Antisocial personality | |||

| Conduct disorder (CD) | 3 | 10 | χ2 (1, N = 44) = 6.304 |

| Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) | 3 | 9 | χ2 (1, N = 44) = 4.919 |

P < 0.05 is significant after correction for multiple comparisons. Only Years of Education was found to be significant (P = 0.003 corrected).

Overall Patient Characteristics

Twenty‐six (57.8%) of the participants were male, with ages ranging from 19 to 49 (M = 34.1, SEM = 8.03). Twenty‐six (57.8%) were of “Hispanic or Latino” ethnicity, and 39 (86.7%) were “White.” Two (4.4%) were “Black or African American,” 1 (2.2%) was “Asian,” and 3 (6.7%) did not report a racial origin. The high proportion of Hispanics is typical for the northern New Mexico region. Twenty‐three (51.1%) had never been married. Years of formal education ranged from 8 to 16 years (M = 11.1, SEM = 1.93).

Four (9.0%) participants were left‐handed or ambidextrous according to the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory criteria [Oldfield, 1971], with scores ranging from −12 to 24 (M = 8.6, SEM = 1.1). Full‐scale WASI scores ranged from 70 to 118 (M = 97.3, SEM = 1.8), with verbal IQ scores of 57 to 128 (M = 94.2, SEM = 2.0), and Performance IQ scores of 63 to 128 (M = 100.7, SEM = 2.0). Participant T‐scores on the WCST ranged from 25 to 65 (M = 45.4, SEM = 1.6) for nonperseverative errors, and from 24 to 80 (M = 51.6, SEM = 2.3) for perseverative errors. The number of completed WCST categories ranged from 0 to 6 (M = 5.2, SEM = 0.2) and failure to maintain set scores ranged from 0 to 5 (M = 1.2, SEM = 1).

All participants met DSM‐IV criteria for stimulant dependence in the 6 months before scanning, with a mean self‐reported frequency of use of “once a week.” Participants were abstinent from stimulants for an average of 40.6 (SEM = 4.9) days before scanning. The age of first stimulant use ranged from 9 to 45 years (M = 19.0, SEM = 0.9), and the duration of use ranged from 2 to 29 years (M = 14.9, SEM = 1.1). Four participants (8.9%) used both cocaine and methamphetamine, 22 (48.9%) used cocaine but not methamphetamine, and 19 (42.2%) used methamphetamine but not cocaine. Although several participants met criteria for other drug use disorders, none were dependent on other substances when scanned.

Participant total CDIS‐IV Axis I lifetime diagnoses ranged from 0 to 6 (M = 2.0, SEM = 0.3), and SA‐45 current (i.e., past 7 days) Positive Symptoms Total (PST) scores ranged from 1 to 44 (M = 18.9, SEM = 1.8). Twelve (26.7%) met Computer‐Assisted SCID II Expert System [CAS II ES, First et al., 2000, 1997] criteria for antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and 13 (28.9%) met criteria for conduct disorder (CD). Data on antisocial behaviors were not available for one participant. Nine (20%) of the participants' fathers, and three (6.7%) of participants' mothers met MAST criteria for alcoholism. Sixteen were unable to make at least one of these assessments because they did not know their biological father/mother.

Behavioral Characteristics of Relapsing and Abstinent Patients

Descriptive and group‐comparison statistics for relapsing and abstinent patients are reported in Table 1. As mentioned above, participants who relapsed to stimulant use had more formal education. No other demographic variables were significantly associated with relapse when corrected for multiple comparisons. Results for all four WCST scales approached or met an uncorrected level of statistical significance, with poorer WCST performance associated with higher incidence of relapse. This agrees with previous studies of WCST performance and treatment drop out rates [Aharonovich et al., 2006].

Self‐reported frequency and quantity of drugs of abuse used recently were negatively associated with relapse. All four participants who used both cocaine and methamphetamine relapsed. No other substance use variables were associated with relapse. There were trends for relapsing patients tended to have higher overall levels of lifetime psychiatric comorbidity and reported higher levels of current psychiatric symptomatology (SA‐45 PST scores), which did not survive tests for multiple comparisons. Follow‐up tests of several CDIS‐IV scales showed trends for higher lifetime/active posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and lifetime/active manic disorder (MANIA) diagnoses that did not survive corrections for multiple comparisons.

Selective Attention Task

Performance on this task was very good. Reaction times averaged 470.78 ms (SD = 61.82) and the hit rate averaged 96.88% (SD = 5.25%), with the false alarm rate to distractors very low, averaging 0.48% (SD = 1.09%) across subjects. Reaction time was slightly slower for the relapsing group (475.26 ms, SD = 62.70) than the abstinent group (466.081, SD = 62.00) but this difference was not significant (t (43) = 0.494, P = 0.624). The false alarm rate for distractors in the relapsing group (0.41%, SD = 0.92%) was also not significantly different from the abstinent group (0.54%, SD = 1.26%), (t (43) =0.388, P = 0.7). However, the relapsing group did respond to significantly fewer targets (95.12%, SD = 6.60%) compared with the abstinent group (98.70%, SD = 2.29), (t (27.442) = 2.443, P = 0.021). However, this was a difference of only 1.5 stimuli on average, and no differences in BOLD responses to target stimuli were found between groups, as described below.

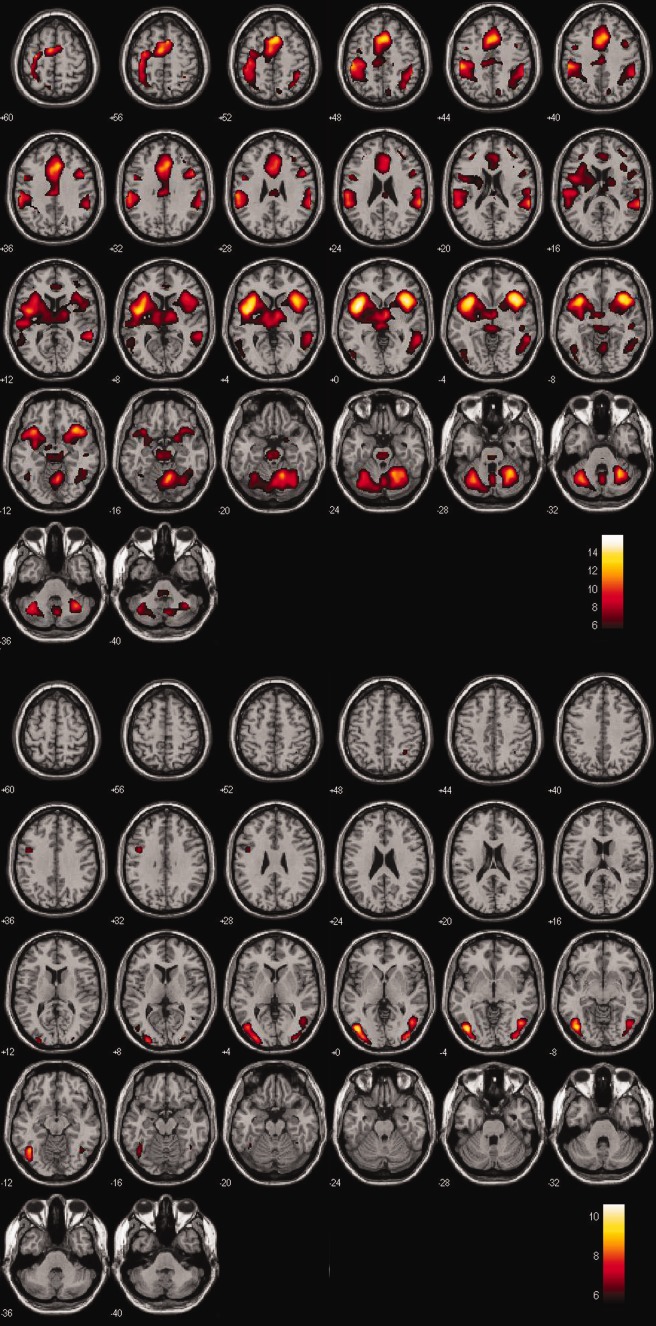

Patients showed typical ER‐fMRI responses evoked by target and distractor stimuli (Fig. 1), similar to previous reports using the visual three‐stimulus oddball task [Clark, 2000; Clark et al., 2002, 2001] and other versions of the oddball task [Kiehl et al., 2005]. As in these previous studies, a much larger volume of response was elicited by target stimuli compared with distractor stimuli.

Figure 1.

Responses to stimuli presented in the three‐stimulus oddball task, averaged over all 45 patients in this study, are shown. Images plotted with the right of the patient on the right of the figure. A. Main effect of BOLD response evoked by target stimuli, plotted with 6 < t < 15. Target‐evoked responses were observed across a wide range of brain regions. B. Main effect of BOLD response evoked by distractor stimuli, plotted with 5 < t < 10. A more restricted pattern of responses to distractor compared with target stimuli were observed, primarily located in bilateral occipital‐temporal and dorsal‐lateral prefrontal cortex. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

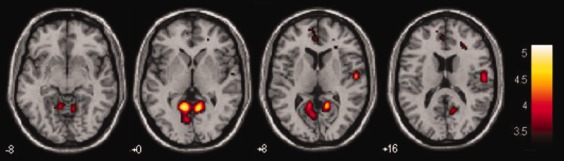

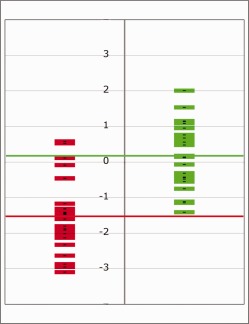

No significant differences were found for target‐evoked BOLD responses between patients who relapsed and those who maintained abstinence. By contrast, a number of regions were found with significant differences between groups in responses to distractor stimuli (Fig. 2). The largest and most significant regions showing significant differences between groups were located in bilateral ventral anterior cingulate, bilateral ventral posterior cingulate, and right insula and adjacent right premotor cortices. The regions of response difference found in bilateral ventral anterior cingulate cortex corresponds with the regions found in our previous studies of healthy control subjects using the same task [Clark et al., 2000, 2001; Clark 2002]. A main effect response to distractor stimuli was not observed in these regions. This may be due to the higher statistical threshold used in the present study, and the high proportion of relapsing patients, may have reduced the significance of this response. Comparison of the t‐values of stimulus‐evoked activity indicated that the responses to distractor stimuli were more significant in patients who remained abstinent when compared with patients who relapsed. Abstinent patients showed a more negative‐going BOLD response evoked by distractor stimuli relative to relapsing patients (Fig. 3), with a larger absolute response amplitude overall.

Figure 2.

Topography of difference in distractor‐evoked BOLD response between relapsing and abstinent subjects is shown. T‐values are plotted with t > 3.38, 0.05 FWE corrected, from 8 mm below to 16 mm above Z = 0. Significant regions of difference between groups were found in bilateral ventral posterior cortex and right insula. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Figure 3.

Shows individual student t values from right posterior cingulate cortex for patients who relapsed (green) versus those who remained abstinent (red) mean t values are plotted as horizontal lines for the relapsing patients (t = 0.15 ± 0.19 SEM; green line) and abstinent patients (t = −1.44 ± 0.23 SEM). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Comparisons between evoked BOLD activity in these regions and other variables showed a significant relationship with years of education for the left posterior cingulate (Pearson's r (45) = 0.52, P = 1.97e−4 and right posterior cingulate (Pearson's r (45) = 0.54, P = 1.56e−4), but not in right insula (Pearson's r (45) = 0.254, P = 0.092). No other significant correlations were found between BOLD response amplitude and patient characteristics such as age, gender, or IQ, or for scores of depression, craving, type and amount of drug use, days of abstinence before or after scanning, or other clinical and demographic variables tested. When years of education were entered as a covariate, the differences between relapsing and abstinent groups remained significant for all three of these regions, including the right insula (F (1,42) = 15.954, P = 2.560e−4) left posterior cingulate (F (1,42) = 4.470, P = 0.035) and right posterior cingulate (F (1,42) = 10.610, P = 0.002). This suggests that this difference between groups in years of education did not fully explain the relationship between BOLD response evoked by distractor stimuli and subsequent relapse.

Prediction of Relapse

We compared a variety of models predicting outcome (abstinence vs. relapse) using behavioral, demographic, and imaging data, as seen in Tables 2 and 3. For the primary analyses, predictors were entered via the forced‐entry method. An exploratory stepwise analysis was conducted to evaluate a predictive model when BOLD signal changes were excluded. Imaging data produced a slightly more accurate and more significant model for prediction of relapse than behavioral data. The behavioral data model included the number of drugs physiologically dependent, years of education, trails B, and loss of set on the WCST. This model classified individuals who relapsed with 75.6% accuracy overall (P = 2.797e−4). Using imaging data alone, including the BOLD response amplitude obtained from the left and right PCC and right insula, discriminated abstinent from relapsing patients with a greater relative accuracy (77.8%) and significance (P = 2.259e−6).

Table 2.

Behavioral data model that predicted relapse

| Predictor | β | Standard error | Wald χ2 | P | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs dependent on | −0.529 | 0.526 | 1.013 | 0.314 | 0.589 |

| Years of education | 0.983 | 0.331 | 8.843 | 0.003 | 2.672 |

| Trails B | −0.030 | 0.048 | 0.526 | 0.028 | 0.971 |

| WCST FMS | 0.974 | 0.431 | 5.12 | 0.024 | 2.649 |

Table 3.

Model of imaging and clinical factors that predicted relapse

| Predictor | β | Standard error | Wald χ2 | P | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right Posterior Cingulate BOLD | 2.595 | .995 | 6.804 | .009 | 13.396 |

| Right Insula BOLD | 1.716 | .732 | 5.496 | .019 | 5.564 |

| Lifetime Manic Episode | 3.464 | 1.578 | 4.819 | .028 | 31.942 |

Other measures were also examined that have been found to be associated with drug use and relapse in previous studies. Psychiatric measures such as a diagnosis of ASPD, behavioral measures such as craving, and combinations of these with other personality/clinical measures, did not do a better job of predicting relapse than the fMRI data alone. Previous studies have observed an effect of ASPD on relapse, and we found here that ASPD status alone predicted relapse with an accuracy of 65.9%. Self‐reported craving was assessed using the Patient Subjective Experience Questionnaire [SEQ‐2D; Miller and Childress, 1994], which asks patients to report their level of craving in the previous two months. This measure resulted in a relatively low accuracy of 58% for predicting relapse. The impact of prior/current PTSD diagnosis was also assessed on the BOLD activation differences between relapses and abstainers. For BOLD amplitude in left and right posterior cingulate and right insula plus PTSD (acute/chronic), accuracy = 84.4% (P = 2.440E−6) and for BOLD plus PTSD (active) accuracy = 84.4% (P = 2.330E−6). This is slightly more accurate than BOLD alone (77.8%), but less accurate and less significant than BOLD plus mania (88.9%). This suggests that there is a very small impact of prior/current PTSD diagnosis on relapse in this group.

This initial patient demographic and clinical model was then combined with the BOLD fMRI data to obtain a more precise model. Signal changes in left‐ and right‐lateralized posterior cingulate cortex were strongly correlated (r (45) = 0.855, P = 7.33e−14). Given a greater predictive contribution of right‐lateralized signal changes, left‐lateralized posterior cingulate signal change was excluded to minimize the effects of multicollinearity. Using logistic regression, we found that a combination of BOLD fMRI signal changes in right‐lateralized posterior cingulate, right insula, and adjacent precentral cortex, along with a diagnosis of a manic episode (lifetime) correctly classified 87.0% of relapsing patients and 90.9% of abstinent patients, correctly classifying 88.9% of participants overall (χ2 (3, N = 45) = 37.969, P = 2.87e−8). When mania was replaced by a diagnosis of ASPD in this model, the accuracy reduced from 89.9% to 81.8%. As described above, when other demographic and psychiatric variables were entered into the models as covariates, such as years of education, none of the variables significantly moderated any of the relationships between group and BOLD signals for the three ROIs tested. Other statistical models using Bayesian logistic regression and multilayer perceptron [Rumelhart et al., 1986] including the same variables were evaluated. We found that they provided comparable accuracy, with Bayesian logistic regression having 84.4% overall accuracy and multilayer perceptron having the best overall accuracy of 91.1%. Multilayer perceptron is a feed‐forward artificial neural network model. These accuracy figures, however, were measured in‐sample, and are likely to be overestimates of true predictive accuracy.

In order to assess the robustness and generality for out‐of‐sample accuracy, these models were tested using a more conservative method of 10‐fold cross‐validation. Overall classifier accuracy varied only slightly across different models, with some differences in sensitivity and specificity, including classical logistic regression (82.2% accuracy, with sensitivity of 87.0% and specificity of 72.3%), Bayesian logistic regression (84.4% with sensitivity of 82.6% and specificity of 86.4%), multilayer perceptron (84.4% with sensitivity of 87.0% and specificity of 81.8%). Decision tree algorithms did most poorly, including basic decision tree (80.0% accuracy) and boosted decision trees (82.2% accuracy).

DISCUSSION

Once stimulant dependence occurs, and then a patient chooses to become abstinent, the return to drug use very often occurs after some period of time. While a variety of factors have been found to correlate with length of abstinence, none of these appear to be highly predictive, nor to provide a useful target for therapy. In the present study, a variety of factors, including behavioral and clinical data, were obtained and compared with fMRI responses for their association with relapse. These data were also used to elucidate brain and cognitive mechanisms underlying relapse to stimulant use, in order to better understand the relapse process, in order to improve methods of treatment.

We present the main findings of these studies: (1) patients with an average of approximately 15 years of stimulant use were tested using ER‐fMRI. (2) Fifty‐one percent of patients relapsed to stimulant use after an average of 81 days of abstinence. (3) Patients who relapsed showed significantly reduced absolute amplitude of BOLD ER‐fMRI responses evoked by rare distractor stimuli presented in the three‐stimulus oddball task, located in bilateral posterior cingulate, right insula, and ventral medial prefrontal cortex. Patients who remained abstinent showed a relatively larger response of negative polarity. (4) No differences were found for ER‐fMRI BOLD activity evoked by target stimuli in this same task, suggesting that global changes in brain function were not present between groups. (5) Two other factors associated with relapse were a lifetime history of mania and years of formal education. (6) A variety of models were tested for the prediction of relapse. The highest in‐sample accuracy (91.1%) was found using a multilayer perceptron neural network that included BOLD fMRI amplitude from right posterior cingulate and insular cortex along with a lifetime history of mania. (7) Testing this model using 10‐fold cross validation showed a slightly lower predictive accuracy, as expected, with classical logistic regression showing the highest sensitivity (87.0%) and Bayesian logistic regression showing the highest specificity (86.4%). (8) Given that all patients were imaged about 3 months before relapse occurred on average (the main outcome measure of this study), then the BOLD differences we find before relapse are, by definition, pre‐existing brain processing differences relative to the main outcome measure of relapse. We conclude that, as these differences in brain function preceded relapse, this suggests that these differences may be related to an increased probability of relapse to stimulant use in a subset of patients.

Comparison With Prior ERP Studies of Relapse

The present study found that a larger amplitude of negative BOLD ER‐fMRI signal, in response to distractor stimuli that was associated with a reduced likelihood of relapse. These results agree with the original results of Bauer 1997, who used the same selective attention task while collecting ERPs in recovering cocaine‐dependent patients. Bauer also found that a reduction in activity evoked by the distractor stimulus in the three‐stimulus oddball task was associated with a higher probability of relapse within 6 months. He also found, as we did here, that target‐evoked responses were not associated with relapse. However, we found 77.8% predictive accuracy using ER‐fMRI, compared with 63% using ERPs [Bauer, 1997]. While there were a number of differences between studies in patient selection, follow‐up methods and so on, it may be that the greater anatomical specificity of fMRI, especially its ability to focus on deeper and smaller brain structures, resulted in greater sensitivity to brain activity associated with relapse. More importantly, the high degree of predictability found between BOLD fMRI activity and relapse supports the idea that functional neuroimaging may prove to be a useful clinical tool to assess relapse susceptibility in individual patients. If such knowledge were available to treatment providers, this could be used to enhance the efficacy and reduce the cost of treatments by matching to different subgroups of patients based on their neural and cognitive predisposition.

While correspondence between ERP and ER‐fMRI responses can be difficult to discern, it is known that the P3 is a positive ERP component recorded from the scalp that typically peaks at 300 ms or later in response to the onset of an eliciting stimulus. Inhibitory potentials result in the efflux of positive ions, resulting in a greater positive ERP component. The present fMRI findings suggest that the same inhibitory processes in ventral anterior and posterior cingulate cortex could result in both increased negative amplitude of BOLD ER‐fMRI response found here, and in increased amplitude of the P3f ERP found in Bauer 1997. This suggests that the same neurocognitive process may result in both a greater negative going BOLD response and an increased positive amplitude of the P3f ERP, and that this process, when diminished in amplitude, is associated with a greater likelihood of relapse. The similar association with relapse, and specificity to distractor but not target‐evoked activity in the same three‐stimulus oddball task, suggest that both the ERP and ER‐fMRI responses are evoked in overlapping brain networks, if not the same neural fields.

Comparison With Prior fMRI Studies of Relapse and Cognitive Function

The present ER‐fMRI results also agree with two prior fMRI studies that examined the pattern of BOLD responses obtained at an early stage of abstinence that differed based on a continued abstinence versus relapse. Paulus et al. 2005 examined 40 treatment‐seeking methamphetamine‐dependent males with less than 1 month of abstinence and tracked abstinence for a median of 370 days. In the 45% who relapsed, BOLD fMRI activation during a two‐choice prediction task differed in right insular, posterior cingulate, and temporal cortices. Kosten et al. [2006] also looked at stimulus‐evoked fMRI activity and subsequent relapse. They studied 17 recovering cocaine‐dependent patients while viewing images of cocaine‐related cues. Worse treatment response correlated with greater BOLD activation in left posterior cingulate cortex among other regions (P < 0.005). These two prior studies, along with the current study, suggest that posterior cingulate may be an important region for mediating behaviors that influence treatment outcome, and may support cognitive or affective functions that help to maintain abstinence.

Ventral posterior cingulate cortex supports a number of cognitive and affective functions that may be related to abstinence. This region is associated with the limbic system [Vogt et al., 2006], which is a collection of brain regions involved with memory encoding and the processing of emotional stimuli. A variety of emotional tasks have been found to generate responses in the ventral posterior cingulate. For instance, activity is elicited in ventral posterior cingulate by personally relevant emotional memory recall and emotional facial expressions [George et al., 1996; Damasio et al., 2000; Phillips et al., 1998], and also self‐reflection and self‐imagery [Johnson et al., 2002; Kircher et al., 2001, 2002; Phan et al., 2004; Sugiura et al., 2005]. When taken together, these functional imaging studies suggest that the ventral posterior cingulate may be involved in the processing of self‐relevant information [Vogt et al., 2006]. This is in contrast to the default‐mode network, which is thought to focus on “internal” information, rather than factual information about ourselves and our relationship with the environment. Deficits in processing of self‐relevant information relative to the environment could result in increased difficulty in maintaining abstinence, including a lack of accurate predictive understanding regarding the potentially harmful effects of a variety of choices, such as associating with active drug users, visiting a place or party where drugs may be used, or engaging in other behaviors where drug use is more likely. Diminished activation of these networks might result in faulty judgment, leading to a higher risk of relapse. Individuals with such deficits might be unable to engage sufficient executive cognition when making decisions that might impact their continued abstinence. This hypothesis is corroborated by post hoc testing of the association between BOLD activity in the PCC and neuropsychological tests of executive function. It was found that the amplitude of distractor‐evoked activity correlated negatively with categories completed (r = −0.398, P = 0.028 when corrected for multiple comparisons) from the WCST. This suggests that the larger the negative amplitude of distractor evoked BOLD response (which is also associated with abstinence), the better patients performed at the WCST task, a measure of executive function.

Along with the ventral posterior cingulate, activity in the insula may also be associated with the assessment of emotionally aversive conditions in the environment. The insula is hypothesized to be involved in the integration of cognitive and affective information [Sawamoto et al., 2000]. FMRI studies have found activation of the insula during the processing of faces expressing fear or disgust [Phillips et al., 1998], during the anticipation of electric shocks [Chua et al., 1999], as well as during script‐evoked sad mood induction [Liotti et al., 2000]. Moreover, insula activity is modulated by the perceptual awareness of threat [Critchley et al., 2002] and penalty [Elliott et al., 2000]. Interestingly, the insular region found here overlap with those found by Naqvi et al. 2007 to be associated with cessation of smoking after lesions in this region. Along with the ventral posterior cingulate, reduced function of this region could also lead to a diminished ability to make a distinction between alternatives that lead to beneficial versus detrimental outcomes.

The lack of differences between groups in response to target stimuli suggests that there were no global hemodynamic differences between groups. If differences between groups were related to hemodynamic differences, responses to all stimuli should have been affected. Instead, responses to distractor stimuli were highly correlated with relapse, while responses to target stimuli were not. Given that BOLD responses to target stimuli covers a larger expanse of brain areas than the response to distractor stimuli, it would be expected to be more affected by global hemodynamic differences rather than less. The important difference between target and distractor stimuli lies in the required motor response to target stimuli, and inhibition of any proponent response elicited by distractor stimuli. This difference suggests that subtle differences in behavioral inhibition may be important for maintaining abstinence.

Another interpretation is that these results may point to a more global deficit in the contribution of cingulate networks to a variety of cognitive functions, which in combination lead to a greater risk for relapse. The fact that differences in overlapping anatomical areas were found by both Kosten et al., [2006] using a drug stimulus task and Paulus et al. 2005 using a 2‐choice prediction task, and the present study using a selective attention task, suggests that it may not be one cognitive function, but rather any cognitive function that involves the same posterior cingulate brain networks. It is quite difficult to identify a specific cognitive process in common with all three of these tasks, aside from very basic ones such as attention, visual perception, and affect, which are involved in all three tasks to some degree.

Comparison With Prior Cognitive and Behavioral Studies of Relapse

Taken together, the present findings suggest that deficits within ventral posterior cingulate and insula could lead to a decreased ability to appraise the relationship between environmental cues and likelihood of relapse, or inhibiting behaviors that promote relapse, making it more difficult to avoid relapse. It has been suggested that relapse is a complex process that involves a variety of factors [Donovan, 1996]. This is supported by the present results, where a multifactorial model that included both imaging and psychiatric assessment domains was found to provide the most accurate prediction of relapse. While deficits in brain circuits predicting the likely consequences of actions given environmental cues may explain the relationship between the imaging results and relapse found in this study, other cognitive processes could also be involved. These might include dysfunction of perceptual and attentional processes, deficits in working memory, or increased impulsivity, among others. The finding of increased impairment on tests of executive function, such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, supports the assertion that there may be deficits in executive function as well. However, the lack of large behavioral differences between relapsing and abstinent patients on response latency and no differences in false alarm rate for the selective attention task suggests that if such differences are present, they are relatively subtle.

Adding a measure of lifetime history of mania to an imaging‐based model increased the accuracy of the model from 77.8% to 89.9%. This may be related to variety of factors, including individual differences in brain networks or neurochemistry that promote the development of both mania and relapse, or changes in brain networks resulting from mania that lead to an increased incidence of relapse. Interestingly, Paulus et al. 2005 also found that mania was associated with relapse in methamphetamine dependence. While neither our findings nor that of Paulus et al. are highly significant, both found that mania, along with a significant finding in posterior cingulate cortex, were related to relapse. The correspondence of these findings across studies suggests that the combination of these measures merits closer examination in future studies, and may offer new targets for treatment to improve treatment outcome.

More years of education were also found to be associated with relapse in this study, and this was also a demographic factor that was significantly correlated with BOLD fMRI activity in posterior cingulate cortex. The precise reason for this relationship is not clear. It may be that other factors associated with years of formal schooling are associated with relapse, such as higher income levels might be correlated with more funds available to obtain stimulants. However, this data were not collected in this study. Therefore it may be that more years of education, or some other variable associated with this, may also be associated with relapse.

Caveats

The data obtained in this study must be considered carefully with regard to a number of factors. First, patients in this study were included only if they did not fulfill criteria for a comorbid drug or alcohol dependence or serious psychiatric illness. Thus, these findings may not generalize to other groups of patients with comorbid psychiatric and drug abuse histories. In addition, the follow‐up period was limited to 6 months, and patients' follow‐ups were ended once relapse occurred, due to limited resources to support a longer duration of intensive follow‐up. One may argue that a longer follow‐up is necessary to substantiate the current finding, and that the degree of relapse, from a single use to consistent use and return to dependence, might provide a more through examination of the relationship between these variables and relapse. The models developed here to predict relapse may also be highly sensitive to the sample characteristics. While we attempted to mitigate this using 10‐fold validation, a follow‐up study would be valuable to confirm and validate these findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Along with previous ERP and fMRI studies that examined brain networks associated with relapse [Bauer, 1997; Kosten et al., 2006; Paulus et al., 2005], the current investigation demonstrates that functional neuroimaging may be useful as a prognostic indicator of relapse potential in stimulant dependence. These differences in brain function precede relapse, and suggest that they might possibly provide a causal basis for increased probability of relapse to stimulant use. Altered activation in brain regions involved in selective and sustained attention, and in processing of the emotional significance and/or self‐relevance of environmental stimuli during decision making, may play a critical role in relapse. Methods that alter activity in these networks might be used to directly test hypotheses regarding causality. Similar methods might also be used as treatments, to improve cognition and behaviors mediated by these networks, and if successful might possibly increase patients' chances for long‐term sobriety and survival.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Lance Bauer and Dr. Victor Hesselbrock for their help in initiating this research, and thanks to Rebecca England, Adam Rosen, Ricardo Blanco, Paul Hicks, Tony DiPasquale, Stefan Posse at the University of New Mexico, and Jill Fries, Michael Doty, and Jeremy Bockholt at the Mind Research Network for help in data collection and analysis, and to our volunteers for their time and effort in making this project a success.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association (2000): Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Aharonovich E, Hasin DS, Brooks AC, Liu X, Bisaga A, Nunes EV (2006): Cognitive deficits predict low treatment retention in cocaine dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend 81:313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO (1997): Frontal P300 decrements, childhood conduct disorder, family history, and the prediction of relapse among abstinent cocaine abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend 44:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg EA (1948): A simple objective technique for measuring flexibility in thinking. J Gen Psychol 39:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Harvey PD (2006): Administration and interpretation of the trail making test. Nat Protoc 1:2277–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht ML, von Mayrhauser C, Anglin MD (2000): Predictors of relapse after treatment for methamphetamine use. J Psychoactive Drugs 32:211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua P, Krams M, Toni I, Passingham R, Dolan R (1999): A functional anatomy of anticipatory anxiety. Neuroimage 9:563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark VP (2002): Orthogonal polynomial regression for the detection of response variability in event‐related fMRI. Neuroimage 17:344–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark VP (2012): A history of randomized task designs in fMRI. Neuroimage 62:1190–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark VP, Fannon S, Lai S, Benson R, Bauer L (2000): Responses to rare visual target and distractor stimuli using event‐related fMRI. J Neurophysiol 83:3133–3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark VP, Fannon S, Lai S, Benson R (2001): Paradigm‐dependent modulation of event‐related fMRI activity evoked by the oddball task. Hum Brain Mapp 14:116–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HD, Mathias CJ, Dolan RJ (2002): Fear conditioning in humans: The influence of awareness and autonomic arousal on functional neuroanatomy. Neuron 33:653–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio AR, Grabowski TJ, Bechara A, Damasio H, Ponto LL, Parvizi J, Hichwa RD (2000): Subcortical and cortical brain activity during the feeling of self‐generated emotions. Nat Neurosci 3:1049–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekhof EK, Falkai P, Gruber O (2008): Functional neuroimaging of reward processing and decision‐making: A review of aberrant motivational and affective processing in addiction and mood disorders. Brain Res Rev 59:164–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM (1991): Assessment issues and domains in the prediction of relapse. Addiction 91(Suppl):S29–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Friston KJ, Dolan RJ (2000): Dissociable neural responses in human reward systems. J Neurosci 20:6159–6165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, Spitzer RL, Benjamin LS (2000): Computer‐Assisted SCID II Expert System for Windows. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi‐ Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (1997): Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV Personality Disorders (SCID‐II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Frawley PJ, Smith JW (1992): One‐year follow‐up after multimodal inpatient treatment for cocaine and methamphetamine dependencies. J Subst Abuse Treat 9:271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire L, Roche A, Mangin JF (2002): What is the best similarity measure for motion correction in fMRI time series? IEEE Trans Med Imaging 21:470–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Ashburner J, Frith CD, Poline JB, Heather JD, Frackowiak RS (1995): Spatial registration and normalization of images. Hum Brain Mapp 3:165–189. [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Harrison L, Penny W (2003): Dynamic causal modeling. Neuroimage 19:1273–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George MS, Ketter TA, Parekh PI, Herscovitch P, Post RM (1996): Gender differences in regional cerebral blood flow during transient self induced sadness or happiness. Biol Psychiatry 40:859–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Craig AD, Bechara A, Garavan H, Childress AR, Paulus MP, Volkow ND (2009): The neurocircuitry of impaired insight in drug addiction. Trends Cogn Sci 13:372–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SC, Baxter LC, Wilder LS, Pipe JG, Heiserman JE, Prigatano GP (2002): Neural correlates of self‐reflection. Brain 125:1808–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehl KA, Stevens MC, Laurens KR, Pearlson G, Calhoun VD, Liddle PF (2005): An adaptive reflexive processing model of neurocognitive function: Supporting evidence from a large scale (n = 100) fMRI study of an auditory oddball task. Neuroimage 25:899–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringelbach ML (2005): The human orbitofrontal cortex: Linking reward to hedonic experience. Nat Rev Neurosci 6:691–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher TTJ, Senior C, Phillips ML, Rabe‐Hesketh S, Benson PJ, Bullmore ET, Brammer M, Simmons A, Bartels M, David AS (2001): Recognizing one's own face. Cognition 78:B1–B15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher TTJ, Brammer M, Bullmore E, Simmons A, Bartels M, David AS (2002): The neural correlates of intentional and incidental self processing. Neuropsychologia 40:683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp WP, Soares B, Farrell M, Silva de Lima M (2007): Psychosocial interventions for cocaine and psychostimulant amphetamines related disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD003023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Scanley BE, Tucker KA, Oliveto A, Prince C, Sinha R, Potenza MN, Skudlarski P, Wexler BE (2005): Cue‐induced brain activity changes and relapse in cocaine‐dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 31:644–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD (1995): Neuropsychological Assessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liotti M, Mayberg HS, Brannan SK, McGinnis S, Jerabek P, Fox PT (2000): Differential limbic–cortical correlates of sadness and anxiety in healthy patients: Implications for affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry 48:30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruish ME (1999): Symptom assessment–45 questionnaire (SA–45) In: Maruish ME, editor. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment, 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR (1996): What is a relapse? Fifty ways to leave the wagon. Addiction 91:S15–S27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Childress AR (1994): Subjective Experience Questionnaire (SEW‐2D). CASAA Research Division. Albuquerque, NM. Ref. 142833.

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS (1996): Assessing drinkers' motivation for change: The stages of change readiness and treatment eagerness scale (SOCRATES). Psychol Addict Behav 10:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi NH, Rudrauf D, Damasio H, Bechara A (2007): Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. Science 315:531–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC (1971): The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9:97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MP, Tapert SF, Schuckit MA (2005): Neural activation patterns of methamphetamine‐dependent subjects during decision making predict relapse. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:761–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan KL, Taylor SF, Welsh RC, Ho SH, Britton JC, Liberzon I (2004): Neural correlates of individual ratings of emotional salience: A trial‐related fMRI study. Neuroimage 21:768–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Young AW, Scott SK, Calder AJ, Andrew C, Giampietro V, Williams SC, Bullmore ET, Brammer M, Gray JA (1998): Neural responses to facial and vocal expressions of fear and disgust. Proc Biol Sci 265:1809–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny AD, Miller BA, Kaplan HB (1972): The brief MAST: A shortened version of the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test. Am J Psychiatry 129:342–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichard D, Theiler J (1994): Generating surrogate data for time series with several simultaneously measured variables. Phys Rev Lett 14:951–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W (1995): Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM‐IV (DIS‐IV). St Louis, MO: Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS (1981): National Institute of Mental Health diagnostic interview schedule. Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 38:381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumelhart DE, Hinton GE, Williams RJ (1986): Learning representations by back‐propagating errors. Nature 323:533–536. [Google Scholar]

- Sawamoto N, Honda M, Okada T, Hanakawa T, Kanda M, Fukuyama H, Konishi J, Shibasaki H (2000): Expectation of pain enhances responses to nonpainful somatosensory stimulation in the anterior cingulate cortex and parietal operculum/posterior insula: An event‐related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurosci 20:7438–7445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seizer ML, Vinokur A, Rooijen L (1975): A self‐administered Michigan short alcoholism screening test. J Stud Alcohol 36:117–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2010): Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Vol. I Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H‐38A, HHS Publication No SMA 10–4586 Findings. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura M, Watanabe J, Maeda Y, Matsue Y, Fukuda H, Kawashima R (2005): Cortical mechanisms of visual self‐recognition. Neuroimage 24:143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR (2002): The inventory of drug use consequences (InDUC): Test‐retest stability and sensitivity to detect change. Psychol Addict Behav 16:165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Drug Intelligence Center (2011). National Drug Threat Assessment 2011. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice.

- Vogt BA, Vogt L, Laureys S (2006): Cytology and functionally correlated circuits of human posterior cingulate areas. Neuroimage 29:452–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]