Abstract

Purpose

To examine whether older adults with vision impairment differentially benefit from cognitive speed of processing training (SPT) relative to healthy older adults.

Methods

Secondary data analyses were conducted from a randomised trial on the effects of SPT among older adults. The effects of vision impairment as indicated by (1) near visual acuity, (2) contrast sensitivity, (3) self-reported cataracts and (4) self-reported other eye conditions (e.g., glaucoma, macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, optic neuritis, and retinopathy) among participants randomised to either SPT or a social- and computer-contact control group was assessed. The primary outcome was Useful Field of View Test (UFOV) performance.

Results

Mixed repeated-measures ancovas demonstrated that those randomized to SPT experienced greater baseline to post-test improvements in UFOV performance relative to controls (p’s < 0.001), regardless of impairments in near visual acuity, contrast sensitivity or presence of cataracts. Those with other eye conditions significantly benefitted from training (p = 0.044), but to a lesser degree than those without such conditions. Covariates included age and baseline measures of balance and depressive symptoms, which were significantly correlated with baseline UFOV performance.

Conclusions

Among a community-based sample of older adults with and without visual impairment and eye disease, the SPT intervention was effective in enhancing participants’ UFOV performance. The analyses presented here indicate the potential for SPT to enhance UFOV performance among a community-based sample of older adults with visual impairment and potentially for some with self-reported eye disease; further research to explore this area is warranted, particularly to determine the effects of eye diseases on SPT benefits.

Keywords: cognitive training, older adults, Useful Field of View Test, visual function

Introduction

Maintaining functional independence is a key factor in preserving older adults’ quality of life. Unfortunately, the prevalence of impairments in cognitive, physical, and visual abilities increases with age and threatens independence.1–4 Relative to younger adults, older adults are at risk for the deleterious effects of cognitive, physical and visual impairments (e.g., falls, hip fractures, decreased social engagement, less time spent in leisure activities, reduced driving mobility, depressive symptoms, and institutionalisation).5–9

Age-related impairments in vision and cognition are particularly common among community-dwelling older adults. Plassman et al.3 found the prevalence of clinically-significant cognitive impairment to be 13.9% among those aged 71 and older. Additionally, nearly 14% of individuals aged 65 and older report experiencing problems with their vision.10 Thus, interventions that can improve cognitive functioning among those with visual impairments are an important target for researchers. The purpose of this paper is to explore whether older adults with visual impairments can benefit from speed of processing training (SPT).

Speed of processing training

The speed of processing hypothesis11 proposes that a variety of cognitive abilities are affected by the speed at which the central nervous system processes information. Previous studies have provided support for this theory by demonstrating that speed of processing accounts for substantial portions of the declines in cognitive performance seen in longitudinal analyses.12–14 It has been recognised that adequate sensory functioning, particularly vision, is a fundamental requirement for normal speed of processing.14

Moreover, studies have consistently shown that speed of processing is associated with everyday functional abilities.15 For example, speed of processing for visual attention, as measured by the Useful Field of View Test (UFOV), is related to performance on instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs),16,17 life space,17,18 and falls.19 Performance on the UFOV also predicts numerous driving outcomes, including on road driving performance,20,21 driving self-regulation and cessation,22–24 and at-fault crash involvement.25 The UFOV is of particular interest because difficulties on this test can be remediated through SPT.26 For healthy older adults, SPT produces immediate improvements in speed of processing and visual attention as measured by UFOV.26–32 Across multiple clinical trials, training effect sizes have ranged from 0.32 to 2.5 standard deviations of improvement relative to control groups.26,28,30,32–35 Additionally, training gains endure over time. Recent data from the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) study showed that ten years post-training, the positive effects of SPT were still evident.36 Among healthy older adults, SPT may also result in significant improvements in the following areas: performance on IADLs;34,36,37 internal locus of control;38 self-rated health;39 depressive symptoms;40 risk of clinical depression;41 gait speed;42 health-related quality of life;43 and annual medical expenditures.44 Older drivers randomised to SPT had 50% lower risk of at-fault crash involvement,45 decreased likelihood of driving cessation,46 and prolonged driving space and exposure.47 What remains unclear is whether persons with visual impairment can benefit from SPT.

Speed of processing training and vision

Vision impairment has been linked to both impaired cognitive speed of processing and driving mobility.14,48 The majority of vision impairment in older adults is caused by reversible or correctable conditions such as cataract and uncorrected refractive error.49,50 While vision-enhancing interventions for these conditions exist, there are many older adults suffering from eye diseases such as age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma which are irreversible.51–55 Even with treatment for these diseases, once vision is impaired it is not likely to return to normal levels of visual functioning. Visual processing speed has been found to be slower in older adults with good visual acuity when compared to younger adults.56 UFOV performance was found to be more variable and mean processing times were higher in adults with glaucoma when compared to healthy controls,57 and UFOV performance is significantly correlated with visual function such that worse vision is related to higher mean processing times.58 In a cross-sectional study utilising structural equation modelling, older age was associated with vision declines which were associated with slowed speed of processing. This in turn was associated with increased deficits in cognition.14 Longitudinal studies of visual decline and cognitive decline support an association between the two. Through analysis of visual and memory data from older adults participating in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Aging, Anstey et al.59 found significant moderate-sized associations between rates of change in vision and memory performance. Additionally, Reyes-Ortiz et al.60 found impairments in near vision to be associated with cognitive decline over time in the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiological Studies of the Elderly.

Given the relationships between vision, speed of processing, and everyday functioning, it is important to know whether SPT is effective among older adults with vision problems. Thus, we conducted secondary data analyses to explore whether older adults with visual impairments benefit from SPT training.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Participants were from the Staying Keen in Later Life (SKILL) study, which examined the impact of SPT on cognitive and everyday functioning in community-dwelling older adults at risk for mobility decline (see Edwards, Wadley et al., 2005,34 for more details). This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional review board approval was obtained. All participants provided informed consent. Participants completed in-person screening and baseline visits at which cognitive and sensory tests were administered. Inclusion criteria for the training portion of the study were: intact vision (distance visual acuity better than 0.60 logMAR (Snellen 6/24 or 20/80); adequate hearing (pure tone average of 40 decibels or better); and intact mental status (Mini-Mental State Exam ≥23).61 In addition, participants needed to exhibit slowed speed of processing (scores on UFOV Subtest 2 ≥ 150 ms or Subtest 3 + 4 ≥ 800 ms) in order to allow room for improvement with cognitive training.

Eligible participants (n = 228) were randomly assigned to a SPT group (n = 120) or a social- and computer- contact (internet training) control group (n = 108). Their average age was 75.2 years (SD = 6.0), and their average educational level was 13.7 years (SD = 2.6). This sample was predominantly female (58%) and Caucasian (82%). Following random assignment, hour-long training sessions were administered twice per week for five weeks, for a total of 10 sessions; all participants included in analyses completed at least eight training sessions. Immediately following training, a post-test assessment was administered by testers who were blind to the group assignment.

Training and control conditions

Speed of processing training involves practising nonverbal, visual exercises that involve identifying and localising targets on a computer screen. Target display speed and task complexity levels are tailored to each individual’s abilities. The overall goal is to increase the speed and accuracy of participants’ visual processing by gradually increasing task complexity and decreasing display speed.28 SPT is commercially available through the AAA Foundation as part of the DriveSharp programme, or through Posit Science as part of the InSight or BrainHQ programs. Training can either be administered in group settings, or can be done independently at home.26,29 Those randomised to the social- and computer- contact (internet training) control condition learned how to use the internet and email, and practised those tasks.

Measures

Near visual acuity

Habitual near visual acuity (with correction, if worn) was measured binocularly using a handheld near vision chart (Good-Lite) at a working distance of 40 cm (16 inches). A near visual LogMAR score accounting for all correctly identified letters was also calculated for each participant. For these secondary data analyses, a LogMAR score of worse than 0.30 was used as the cut point for impairment. This equates to visual acuity of Snellen 6/12 (20/40) or worse, a commonly-used definition for visual impairment.62 Participants were dichotomised as impaired vs non-impaired. A total of 18 participants (seven in the SPT group, 11 in the internet group) had impaired near visual acuity.

Contrast sensitivity

Letter contrast sensitivity at baseline was assessed binocularly (with habitual correction) using the Pelli-Robson Contrast Sensitivity chart.63 Scores were derived from the last set of triplets in which two letters were identified correctly, and the possible score range was 0.00 (poorest performance) to 2.25 log10 (best performance). For these secondary analyses, a score of ≤1.5 was used as the cut point for impairment, in keeping with recommended guidelines.63 Participants were dichotomised as impaired vs non-impaired under that criterion. A total of 57 participants (30 in the SPT group, 27 in the internet group) had impaired contrast sensitivity.

Eye health conditions

At baseline, participants reported whether or not a doctor or nurse had ever diagnosed them with cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, optic neuritis, or retinopathy. The most common condition was cataracts. For the purposes of these secondary data analyses, participants were dichotomised as having vs not having a history of cataracts. A total of 140 participants reported being diagnosed with this condition (69 in the SPT group, 71 in the internet group). Because the other eye conditions had very small sample sizes per group when considered individually, we combined them into one dichotomous variable, ‘eye health conditions,’ for the purpose of these analyses. Participants who reported at least one non-cataract eye condition were coded as having ‘eye health conditions.’ A total of 59 participants met this criterion (30 in the SPT group, 29 in the internet group).

Physical performance

The Turn 360° Test64 was used as an indicator of balance and overall physical performance at baseline. Participants were twice asked to stand and turn in a complete circle. Observers recorded the number of steps required to complete each turn, and fewer steps indicated better performance. Acceptable test-retest reliability for this test has been established in older adults (Pearson’s r = 0.83).65 The average number of steps across the two turns was used as a covariate in current analyses due to a significant correlation with baseline UFOV performance.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed via the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D).66 This scale contains 20 items that measure how often respondents have experienced various symptoms over the past week, ranging from 0 = rarely to 3 = most of the time. A higher total score indicates more depressive symptoms. This scale has proven internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and validity.66 This variable was used as a covariate in current analyses due to a significant correlation with baseline UFOV performance.

Useful Field of View Test

The SKILL study used the PC, touch, four-subtest version of the Useful Field of View Test (UFOV) to measure speed of processing at baseline and post-test.34 UFOV includes four subtests that progressively increase in difficulty (r = 0.74–0.81 test-retest reliability).58 In each subtest, targets are presented at durations ranging from 16.67 to 500 ms, and scores are the display durations at which participants respond correctly 75% of the time. The first subtest requires participants to identify a target (a silhouette of either a car or truck) that appears in a fixation box in the centre of the screen. The second subset requires participants to identify the central target and simultaneously localise a peripheral target, and the third subtest is the same as the second subtest, except the peripheral target is embedded in visual distractors. Finally, the fourth subtest involves the presentation of two objects in the central fixation box, and participants must indicate whether these objects are the same or different. The current study used the overall score across the four subtests of UFOV, which can range from 66.68 to 2000 ms, measured at baseline and post-test to assess change in cognitive speed of processing. Lower scores indicate faster performance.

Analyses

Four dichotomous variables for vision were created for the present analyses to define vision impairment subgroups as detailed in the ‘Measures’ section above. The subgroups included those with and without (1) impaired near visual acuity, (2) impaired contrast sensitivity, (3) history of cataracts, or (4) self-reported eye health conditions. Cut-points for visual impairment were defined based on prior research.62,63 All significance tests were at p < 0.05, two-tailed.

Analyses consisted of four separate, three-way, mixed between-within ancovas. For each model, UFOV performance was the outcome, each visual impairment variable (yes or no) and experimental group (training or control) were between subjects factors, and time (baseline or post-test) was a within subjects factor. Covariates included baseline demographic or health variables that had significant bivariate correlations with baseline UFOV performance. Baseline age (r = 0.25), Turn 360 performance (r = 0.34), and depressive symptoms (r = 0.32) met this criterion. Years of education and number of co-morbidities were also examined as potential covariates, but these variables were not significantly correlated with baseline UFOV performance and were not included in analyses.

In these models, a significant group by time interaction would demonstrate that training improved UFOV performance irrespective of visual impairment. In the absence of other significant interactions, this finding would indicate that participants with visual impairment showed similar training gains relative to their peers without vision problems. Any significant three-way interactions between visual impairment by training group by time were followed with a mixed ancova within that visually impaired subgroup sample. In these subsample analyses, UFOV performance across baseline to post-test was examined as a repeated-measures factor and training group as a between-subjects factor, adjusting for the covariates as detailed above.

Results

The analytic sample included 208 participants (n = 105 in the SPT group, n = 103 in the internet training control group). Twenty participants were missing from the final analyses; 13 of the SPT participants and five of the control participants were missing post UFOV scores. Additionally two participants, both from the SPT condition, were missing a yes/no response on the cataract question and were excluded from the analyses. Mean UFOV scores for each vision impairment factor by training group at baseline and post-test are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Useful Field of View (UFOV) Means and Standard Deviations for each Vision Factor Group and Training Group at Baseline and Post-test’

| Baseline |

Post-test |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls |

SPT |

Controls |

SPT |

|||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |

| Near Visual | ||||||||

| Acuity | ||||||||

| Impaired | 11 | 1204.6 (239.6) | 7 | 1143.3 (301.0) | 11 | 1029.2 (292.5) | 7 | 642.7 (148.3) |

| Non-impaired | 89 | 1107.5 (192.3) | 100 | 1108.7 (210.1) | 89 | 988.0 (216.3) | 100 | 684.1 (220.4) |

| Contrast | ||||||||

| Sensitivity | ||||||||

| Impaired | 25 | 1211.6 (211.8) | 29 | 1139.9 (285.5) | 25 | 1080.4 (264.1) | 29 | 739.0 (230.5) |

| Non-impaired | 75 | 1087.0 (185.8) | 78 | 1100.2 (208.1) | 75 | 963.25 (203.2) | 78 | 660.0 (208.0) |

| Self-reported | ||||||||

| Cataracts | ||||||||

| Yes | 64 | 1115.6 (174.6) | 64 | 1127.4 (226.2) | 64 | 1024.8 (220.7) | 64 | 698.3 (216.7) |

| No | 36 | 1122.7 (239.1) | 41 | 1092.7 (201.0) | 36 | 935.2 (222.6) | 41 | 663.2 (218.1) |

| Self-reported Eye | ||||||||

| Health Conditions | ||||||||

| Yes | 29 | 1183.3 (206.5) | 30 | 1095.7 (209.6) | 29 | 1033.3 (248.3) | 30 | 732.7 (215.7) |

| No | 71 | 1091.5 (191.0) | 77 | 1116.9 (218.8) | 71 | 975.9 (213.6) | 77 | 661.4 (214.4) |

When examining the impaired near visual acuity factor, ancova revealed there was a significant effect of time, Wilks’ Λ = 0.93, F1,200 = 15.5, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.07, and a significant interaction between training group and time, Wilks’ Λ = 0.83, F1,200 = 39.7, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.17. The near visual impairment by group by time three-way interaction was not significant, Wilks’ Λ = 0.99, F1,200 = 0.22, p = 0.64, partial η2 = 0.001. The estimated marginal means showed that UFOV performance improved more for the SPT group than the control group. Older adults randomised to SPT experienced greater UFOV improvements regardless of whether or not they had impaired near visual acuity.

When examining the contrast sensitivity factor, ancova revealed significant effect of time, Wilks’ Λ = 0.94, F1,200 = 11.8, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.06, and a significant interaction between training group and time, Wilks’ Λ = 0.71, F1,200 = 80.6, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.28. The contrast sensitivity by group by time three-way interaction was not significant, Wilks’ Λ = 0.99, F1,200 < 1, p = 0.46, partial η2 = 0.002. The estimated marginal means showed that UFOV performance improved more for the SPT group than the control group. Thus, older adults randomised to SPT experienced greater improvements in UFOV than the control condition regardless of whether or not they had impaired contrast sensitivity.

With regard to the effects of cataract, ancova revealed there was a significant effect of time, Wilks’ Λ = 0.94, F1,198 = 12.4, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.06, and a significant interaction between training group and time, Wilks’ Λ = 0.67, F1,198 = 96.5, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.33. The three way interaction between cataract, group, and time was not significant, Wilks’ Λ = 0.99, F1,200 = 2.17, p = 0.14, partial η2 = 0.011. Thus, older adults with and without self-reported cataract who were randomised to SPT showed significant training gains relative to controls.

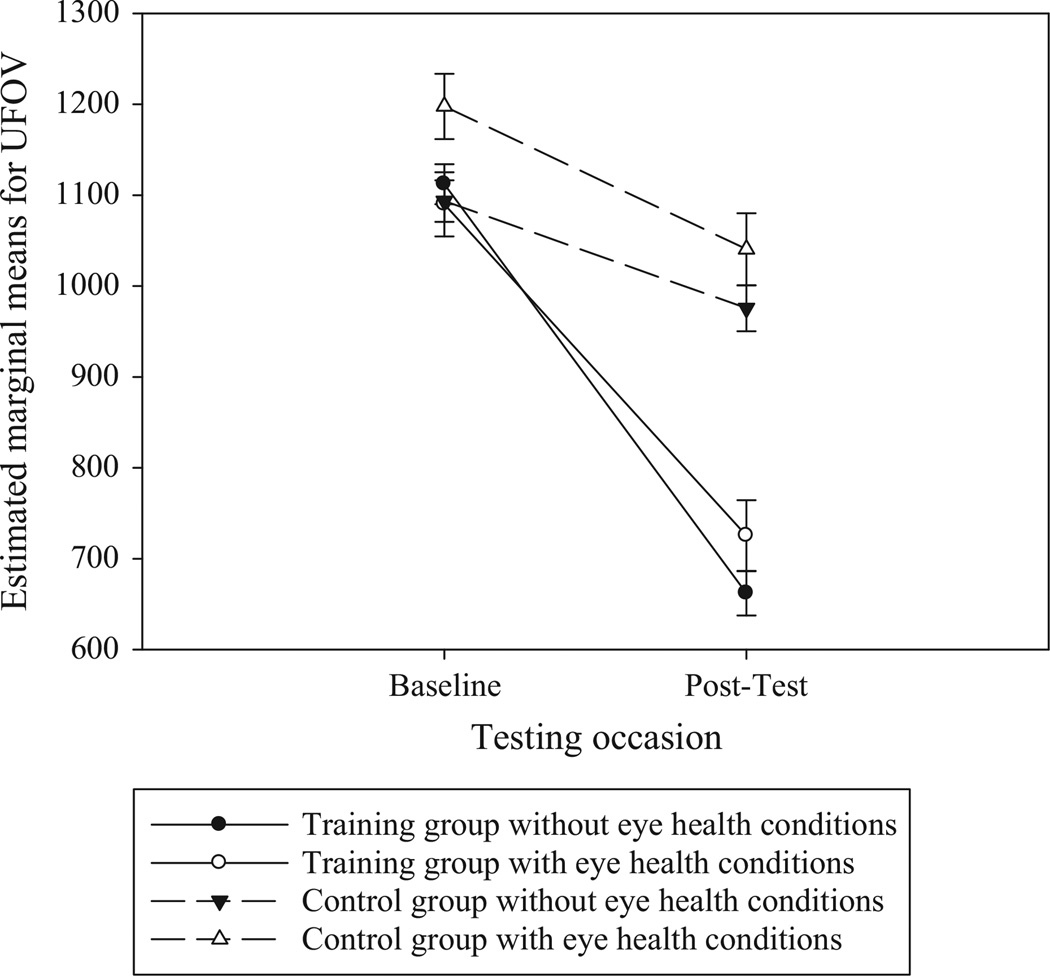

When examining the effects of eye health conditions, ancova revealed there was a significant effect of time, Wilks’ Λ = 0.94, F1,200 = 12.6, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.06, and a significant interaction between training group and time, Wilks’ Λ = 0.72, F1,200 = 77.3, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.28. The three-way time by training group by eye health conditions interaction was also significant, Wilks’ Λ= 0.98, F1,200 = 4.13, p = 0.044, partial η2 = 0.02. To examine if the effects of training on UFOV performance were significant among those with other eye conditions, we conducted an additional ancova among the subsample of participants with other eye conditions. This subsample included 30 from the SOPT group and 29 from the control group who reported a significant eye condition. When examining just those participants with significant eye conditions, the training group by time interaction was still significant, F1,54 = 13.3, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.19. A graph of the estimated marginal means shows more improvement in UFOV for the SPT group vs the internet group for those with significant eye conditions (Figure 1). These findings suggest that older adults with eye conditions other than cataracts may also benefit from SPT. However, the benefit received from training among those with other eye condition is of a smaller magnitude relative to those without such conditions.

Figure 1.

Estimated Marginal Means of UFOV Performance across Occasions and Training Groups for Participants with and without Eye Health Conditions. n = 59 participants had eye health conditions (30 in the SPT group, 29 in the internet group). Covariates were evaluated at the following values: age in years = 75.1, Turn 360 performance at baseline = 7.18, depressive symptoms at baseline = 7.95. Error bars represent standard errors.

With regard to the effects of covariates, in each model, there was a significant interaction between time and age (p’s < 0.01), as well as with time and Turn360 (p’s < 0.05). Those who had poorer balance as indicated by Turn 360 tended to perform worse on UFOV at baseline. Older participants tended to perform better on UFOV at post-test.

Discussion

We examined whether SPT could enhance UFOV performance in a sample of older adults with visual impairment and self-reported eye disease using secondary data analyses. The results of the analyses indicate that among a community-based sample of older adults with visual impairment and eye disease, the SPT intervention was effective in enhancing participants’ speed and accuracy of visual processing as measured by UFOV performance. These results provide preliminary evidence that the presence of visual impairment and eye disease may not prevent older adults from experiencing benefits from SPT. This is important knowledge as this is the first study to specifically show evidence that the benefits of SPT can extend to older adults with visual impairment. To date, the majority of research on SPT has focussed on healthy older adults. However, the benefits of SPT have also been found to extend to older adults with HIV,51,52 stroke,53 potential mild cognitive impairment,54 memory impairment,55 and Parkinson’s disease.56 In a recent review of visual processing speed, Owsley67 reflects on previous work finding that deficits in visual processing speed are not always attributed to impairments in visual acuity or contrast sensitivity. However, little work has been done in investigating the benefits of SPT in persons with visual impairment. Owsley cited only one study68 which investigated the ability to measure UFOV in people with low vision, but this study did not examine the benefits of SPT in people with low vision. Owsley concluded that further work is needed to determine if, and to what extent, visually impaired older adults could benefit from speed of processing training.67 The findings from our study begin to answer this question.

Whereas those with impaired near visual acuity or contrast sensitivity as well as those with self-reported cataracts did not differentially benefit from training, the effects of training were smaller among those with self-reported eye health conditions (glaucoma, macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, optic neuritis, or retinopathy). Further research regarding the effect of each of these eye diseases individually on older adults’ ability to benefit from SPT is warranted. The small sample size for each of these conditions in the current study precludes us from exploring that here.

Previous studies have established that, for healthy older adults, at least 10 sessions of SPT produces immediate improvements in speed of processing and visual attention as measured by UFOV, and participants with initially slower speed of processing appear to benefit most.26–35 Moreover, training gains endure over time. Recent data from the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) study showed large effects of SPT on targeted cognitive abilities ten years post-training.36 The present study suggests that training effects are also evident after 10 sessions of SPT in older adults with visual impairments.

There are a few limitations to the present study. First, the SKILL study was not designed to specifically examine visual impairment. The subgroup analyses conducted in this manuscript were not pre-specified. Such post-hoc subgroup comparisons should be interpreted with caution and require confirmation by future study. The subgroups of older adults with visual impairment from the SKILL study may not adequately represent the population of older adults with such vision difficulties. For example, in the SKILL study habitual distance visual acuity of 0.60 logMAR (Snellen 6/24 or 20/80) or better was part of the eligibility criteria, and only three people did not meet this criterion.

Although the prevalence of near vision impairment was low at 8% of the sample, significant improvements on UFOV performance were detected among those with near visual impairments who received SPT training vs the control group. Since near vision was measured with use of habitual correction if worn, it is possible some of the participants did not wear their reading spectacles and this could have influenced our results. However, participants were reminded to bring and wear their habitual correction to all appointments. Twenty-five percent of the sample had impaired contrast sensitivity and again, those who received SPT training experienced greater improvements in UFOV performance than the control group. Since the sample sizes in each group were small, the reliability and generalisability of the ancova findings may be limited. Power analyses69 indicated a sample size of 52 for ancovas with three covariates and a two-tailed test with α = 0.05 has 80% power to detect a large effect size (as previously demonstrated for SPT).26,28,30,32–35 Thus, the near visual acuity subgroup analyses were not sufficiently powered, but the other subgroup analyses were sufficiently powered.

Another limitation is the use of dichotomous variables for eye diseases due to small sample of people with these conditions. Additionally, in this study 61% of the sample reported a history of cataracts while previous population estimates for those aged 65 and older have been lower at 39%.70 It is possible that there may be measurement error as these were self-reported data and participants were asked if they had ever been told by a doctor or nurse that they have cataracts. It is possible that some people responded to this question in a positive manner (yes) even if they have already had the cataract removed. This is a limitation of these analyses. Future studies should confirm presence of cataracts through participants’ medical records. Finally, it is a limitation that UFOV performance was the only outcome in these analyses. While it is the primary outcome of interest in measuring the effects of SPT, there remains a need to explore if SPT benefits transfer to other outcomes in older adults with vision impairment and eye disease. The benefits of SPT on other outcomes are numerous. Most importantly, the gains experienced through SPT have been found to transfer to several health and functional outcomes, including IADL performance, complex reaction time, driving safety and mobility, internal locus of control, self-rated health, depressive symptoms, risk of clinical depression, health-related quality of life, and annual medical expenditures.28,32,34–47 It will be important for future work to investigate whether gains experienced through SPT also transfer in these same areas in people with visual impairments. The analyses presented here indicate the potential for SPT to enhance speed of processing and visual attention for older adults with vision impairments. However, further work in this area is warranted.

This study presents promising findings that the benefits of SPT may extend to older adults with vision impairment and eye disease, a previously understudied population. The results suggest that older adults with vision impairment and eye disease should be included in SPT studies. Further research in this area is needed to explore the effects of SPT in a more diverse range of visual impairment and in a larger proportion of people with clinically diagnosed eye disease with the potential to cause vision impairment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging grant 5 R37 AG05739-16, Improvement of Visual Processing in Older Adults, Karlene K. Ball, principal investigator. The authors also wish to acknowledge Dr. Karlene K. Ball, who was awarded the MERIT grant to conduct the SKILL study, and the investigators of SKILL, Drs. Daniel Roenker, Lesley Ross, David Roth, Virginia Wadley, and David Vance.

Biographies

Amanda F. Elliott is currently an Assistant Professor in the College of Nursing at the University of South Florida in Tampa, FL. She completed her BSN, MSN, and PhD in Nursing at the University of Florida. She then completed post-doctoral fellowships in the Center for Mental Health and Aging at the University of Alabama and in the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. She was also an ORISE Fellow with the Vision Health Initiative at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Her main research interests are in the areas of visual impairment and cognitive performance in older adults.

Melissa L. O’Connor received a master’s degree in Experimental Psychology from the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh, and a PhD in Aging Studies from the University of South Florida. She also completed a post-doctoral fellowship in Quantitative Psychology at the University of Virginia. Her research focuses on characterizing changes in cognitive and functional abilities across the adult lifespan, and her ultimate goal is to promote healthy aging. Specifically, her research interests include: examining age-related differences and changes in cognitive and functional abilities, such as driving, among healthy adults and clinical populations; quantitative methods and psychometrics; interventions for improving cognition, health, and everyday functioning; and attitudes toward dementia.

Jerri D. Edwards is currently an Associate Professor in the School of Aging Studies at the University of South Florida in Tampa, FL. She is also the Director of the Cognitive Aging Lab. She received her BA in Psychology from Anderson University, an MA in Experimental Psychology from Western Kentucky University, and a PhD in Developmental Psychology from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. She then completed a post-doctoral fellowship in Cognitive Aging in the Center for Research on Applied Gerontology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. She is particularly interested in how cognitive interventions help older adults to avoid or at least delay functional difficulties and thereby maintain independence. Much of her work has focused upon the functional ability of driving including assessing driving fitness among older adults and cognitive training strategies to remediate cognitive decline that results in driving difficulties.

Footnotes

Disclosures

From June to August 2008, Dr. Edwards worked as a limited consultant to Posit Science who currently markets the UFOV test and speed of processing training software (now called Insight and as part of the BrainHQ program). Drs. Elliott and O’Connor report no conflicts of interest and have no proprietary interest in any of the materials mentioned in this article.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2013;9:208–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevent Blindness America, National Eye Institute. The Vision Problems in the U.S.: Prevalence of Adults Vision Impairment and Age-Related Eye Disease in America. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plassman BL, Lange KM, McCammon RJ, et al. Incidence of dementia and cognitive impairment, not dementia in the United States. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:418–426. doi: 10.1002/ana.22362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daly RM, Rosengren BE, Alwis G, Alhborg HG, Sernbo I, Karlsson MK. Gender specific age-related changes in bone density, muscle strength and functional performance in the elderly: a 10-year prospective population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-13-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crews JE, Campbell VA. Vision impairment and hearing loss among community-dwelling older Americans: implications for health and functioning. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:823–829. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitson H, Cousins S, Burchett B, et al. The combined effect of visual impairment and cognitive impairment on disability in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:885–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J, Mitchell P, Cumming R, et al. Visual impairment and nursing home placement in older Australians: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2003;10:3–13. doi: 10.1076/opep.10.1.3.13773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West C, Gildengorin G, Haegerstrom-Portnoy G, et al. Is vision function related to physical functional ability in older adults? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:136–145. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black SA, Rush RD. Cognitive and functional decline in adults aged 75 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1978–1986. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Peregoy JA. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2011. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 10. 2012;252:1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salthouse TA. The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychol Rev. 1996;103:403–428. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkel D, Pedersen NL. Processing speed and longitudinal trajectories of change for cognitive abilities: the swedish adoption/twin study of aging. Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2004;11:325–345. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemke U, Zimprich D. Longitudinal changes in memory performance and processing speed in old age. Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2005;12:57–77. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clay OJ, Edwards JD, Ross LA, et al. Visual function and cognitive speed of processing mediate age-related decline in memory span and fluid intelligence. J Aging Health. 2009;21:547–566. doi: 10.1177/0898264309333326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vance DE. Speed of processing in older adults: a cognitive overview for nursing. The J Neurosci Nurs. 2009;41:290–297. doi: 10.1097/jnn.0b013e3181b6beda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owsley C, Sloane ME, McGwin G, Jr, Ball KK. Timed instrumental activities of daily living tasks: relationship to cognitive function and everyday performance assessments in older adults. Gerontology. 2002;48:254–265. doi: 10.1159/000058360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood KM, Edwards JD, Clay OJ, Wadley VG, Roenker DL, Ball KK. Sensory and cognitive factors influencing functional ability in older adults. Gerontology. 2005;51:131–141. doi: 10.1159/000082199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stalvey BT, Owsley C, Sloane ME, Ball KK. The Life Space Questionnaire: a measure of the extent of mobility of older adults. J Appl Gerontol. 1999;18:460–478. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vance DE, Ball KK, Roenker DL, Wadley WG, Edwards JD, Cissell GM. Predictors of falling in older Maryland drivers: a structural-equation model. J Aging Phys Act. 2006;14:254–269. doi: 10.1123/japa.14.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anstey KJ, Wood JM. Chronological age and age-related cognitive deficits are associated with an increase in multiple types of driving errors in late life. Neuropsychology. 2011;25:613–621. doi: 10.1037/a0023835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood JM, Chaparro A, Lacherez P, Hickson L. Useful field of view predicts driving in the presence of distracters. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89:373–381. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31824c17ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edwards JD, Bart E, O’Connor ML, Cissell GM. Ten years down the road: predictors of driving cessation. Gerontologist. 2010;50:393–399. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwards JD, Ross LA, Ackerman ML, et al. Longitudinal predictors of driving cessation among older adults form the active clinical trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63:6–12. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.1.p6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Connor ML, Edwards JD, Small BJ, Andel R. Patterns of level and change in self-reported driving behaviors among older adults: who self-regulates? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67:437–446. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ball KK, Roenker DL, Wadley VG, et al. Can high-risk older drivers be identified through performance-based measures in a Department of Motor Vehicles setting? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolinsky FD, Vander Weg M, Howren MB, Jones MP, Dotson MM. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive training using a visual speed of processing intervention in middle aged and older adults. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ball KK, Berch DB, Helmers KF, et al. Effects of cognitive training interventions. JAMA. 2002;288:2271–2281. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ball KK, Edwards JD, Ross LA. The impact of speed of processing training on cognitive and everyday functions. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62:19–31. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.special_issue_1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wadley VG, Benz RL, Ball KK, Roenker DL, Edwards JD, Vance DE. Development and evaluation of home-based speed-of-processing training for older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:757–763. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edwards JD, Valdés EG, Peronto C, et al. The efficacy of insight cognitive training to improve Useful Field of View performance: a brief report. [accessed 3/7/14];J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vance DE, Dawson J, Wadley V, et al. The Accelerate study: the longitudinal effect of speed of processing training on cognitive performance of older adults. Rehabil Psychol. 2007;52:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willis SL, Tennstedt SL, Marsiske M, et al. Long-term effects of cognitive training on everyday functional outcomes in older adults. JAMA. 2006;296:2805–2814. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.23.2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ball KK, Ross LA, Roth DL, Edwards JD. Speed of processing training in the ACTIVE study: how much is needed and who benefits? J Aging Health. 2008;25:65S–84S. doi: 10.1177/0898264312470167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edwards JD, Wadley VG, Vance DE, Roenker DL, Ball KK. The impact of speed of processing training on cognitive and everyday performance. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9:262–271. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331336788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roenker DL, Cissell GM, Ball KK, Wadley VG, Edwards JD. Speed of processing and driving simulator training result in improved driving performance. Hum Factors. 2003;45:218–233. doi: 10.1518/hfes.45.2.218.27241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rebok GW, Ball KK, Guey LT, et al. Ten-year effects of the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly cognitive training trial on cognition and everyday functioning in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:16–24. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards JD, Wadley VG, Myers R, Roenker DL, Cissell GM, Ball KK. Transfer of a speed of processing intervention to near and far cognitive functions. Gerontology. 2002;48:329–340. doi: 10.1159/000065259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolinsky FD, Vander Weg MW, Martin R, et al. Does cognitive training improve internal locus of control among older adults? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;65:591–598. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolinsky FD, Mahncke H, Vander Weg MW, et al. Speed of processing training protects self-rated health in older adults: enduring effects observed in the multi-site ACTIVE randomized controlled trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:470–478. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209991281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolinsky FD, Vander Weg MW, Martin R, et al. The effect of speed-of-processing training on depressive symptoms in ACTIVE. J Gerontol A: Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:468–472. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolinsky FD, Mahncke HW, Weg MWV, et al. The ACTIVE cognitive training interventions and the onset of and recovery from suspected clinical depression. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:577–585. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith-Ray RL, Hughes SL, Prohaska TR, Little DM, Jurivich DA, Hedeker D. Impact of cognitive training on balance and gait in older adults. [accessed 3/7/14]; [accessed 3/7/14];J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolinsky FD, Unverzagt JW, Smith DM, Jones R, Stoddard A, Tennstedt SL. The ACTIVE cognitive training trial and health-related quality of life: protection that lasts for 5 years. J Gerontol A: Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:1324–1329. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.12.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolinsky FD, Mahncke H, Kosinski M, et al. The ACTIVE cognitive training trial and predicted medical expenditures. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:109. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ball KK, Edwards JD, Ross LA, McGwin G. Cognitive training decreases motor vehicle collision involvement among older drivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2107–2113. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edwards JD, Delahunt PB, Mahncke HW. Cognitive speed of processing training delays driving cessation. J Gerontol A: Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1262–1267. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edwards JD, Myers C, Ross LA, et al. The longitudinal impact of cognitive speed of processing training on driving mobility. Gerontologist. 2009;49:485–494. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freeman EE, Munoz B, Turano KA, West SK. Measures of visual function and time to driving cessation in older adults. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82:765–773. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000175008.88427.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tielsch JM, Javitt JC, Coleman A, Katz J, Sommer A. The prevalence of blindess and visual impairment among nursing home residents in Baltimore. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1205–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedman DS, West SK, Munoz B, et al. Racial variations in causes of vision loss in nursing homes: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation in Nursing Home Groups (SEEING) Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1019–1024. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.7.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klein R, Chou CF, Klein BE, Zhang X, Meuer SM, Saaddine JB. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;29:75–80. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eye Disease Prevalence Research Group. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:552–563. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang X, Saaddine JS, Chou C, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United States, 2005–2008. JAMA. 2010;304:649–656. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Friedman DS, Wolfs RC, O’Colmain BJ, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:532–538. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Congdon N, Vinderling JR, Klein BE, et al. Prevalence of cataract and pseudophakia/aphakia among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:487–494. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jackson GR, Owsley C. Visual dysfunction, neurodegenerative diseases, and aging. Neurol Clin N Am. 2003;21:709–728. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(02)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bentley SA, LeBlanc RP, Nicolela MT, Chauhan BC. Validity, reliability, and repeatability of the useful field of view test in persons with normal vision and patients with glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:6763–6769. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Edwards JD, Vance DE, Wadley VG, Cissell GM, Roenker DL, Ball KK. Reliability and validity of the Useful Field of View Test scores as administered by personal computer. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2005;27:529–543. doi: 10.1080/13803390490515432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anstey KJ, Hofer SM, Luszcz MA. A latent growth curve analysis of late-life sensory and cognitive function over 8 years: evidence for specific and common factors underlying change. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:714–726. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.4.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reyes-Ortiz CA, Kuo Y, DiNuzzo AR, Ray LA, Raji MA, Markides KS. Near vision impairment predicts cognitive decline: data from the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:681–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elliott AF, McGwin G, Owsley C. Vision impairment among older residents in assisted living. J Aging Health. 2013;25:364–378. doi: 10.1177/0898264312472538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pelli DG, Robson JG, Wilkins AJ. The design of a new letter chart for measuring contrast sensitivity. Clin Vision Sci. 1988;2:187–199. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steinhagen-Thiessen E, Borchelt M. Morbidity, medication, and functional limitations in very old age. In: Baltes PB, Mayer KU, editors. Baltes & Mayer’s the Berlin Aging Study: Aging from 70 to 100. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 131–166. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tager IB, Swanson A, Satariano WA. Reliability of physical performance and self-reported functional measures in an older population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53:M295–M300. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.4.m295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Owsley C. Visual processing speed. Vision Res. 2013;2013:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leat S, Lovie-Kitchen J. Visual impairment and the useful field of vision. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2006;26:392–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2006.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of visual impairment and selected eye diseases among persons aged ≥ 50 years with and without diabetes—United States, 2002. MMWR. 2004;53:1069–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]