A 51-year-old man was referred to our hospital in Lilongwe with 6 months of diffuse progressive lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly with fever, chills, night sweats, and weight loss. He had been on antiretroviral therapy for HIV for 5 years, and his CD4 cell count was 234 cells per μL and HIV RNA was 357 copies per mL. Fine needle aspiration of a lymph node suggested Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Immunohistochemistry reagents were temporarily out of stock, as sometimes happens in Malawi. We started chemotherapy with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine while waiting for results of a confirmatory biopsy sample. Lymphoma is often diagnosed by fine needle aspiration in sub-Saharan African settings,1 and we often have to start treatment on the basis of less complete diagnostic information than is available in resource-rich settings.

The patient responded to his first chemotherapy dose, but on review in our weekly telepathology conference we felt the lymph node biopsy sample might have been reactive to infection, possibly to his HIV, and after extensive discussion we stopped chemotherapy. 2 months later he developed worsening hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, fatigue, and oedema. Blood tests showed progressive anaemia (haemoglobin 57 g/L), thrombocytopenia (platelets 32 × 109/L), hyponatraemia (sodium 123 mmol/L), and hypoalbuminaemia (albumin 21 g/L), and bone marrow biopsy sampling showed reactive plasmacytosis. Immunohistochemistry reagents had been resupplied in the interim, and latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) staining of repeat lymph node specimen showed multicentric Castleman’s disease (figure). Plasma viral load of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), tested with research collaborators in the USA, was 50 000 copies per mL. We started the patient on etoposide, with improvement of his lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and laboratory values. We are monitoring him closely for relapse. We have not seen Kaposi sarcoma clinically or on examination of lymph node specimens.

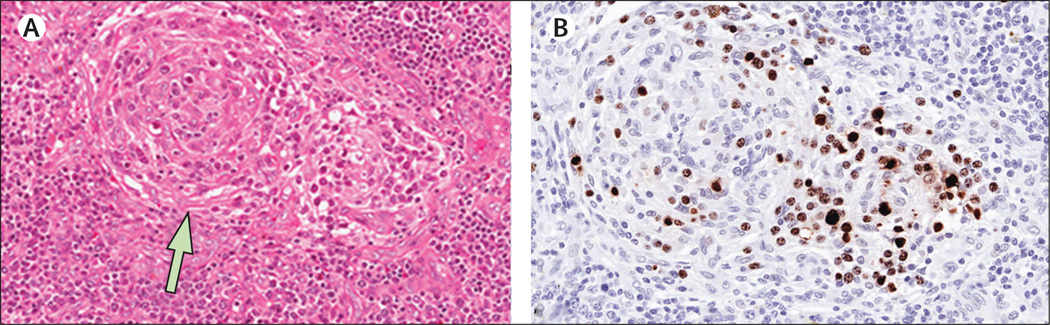

Figure. Lymph nodes showing multicentric Castleman’s disease and Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus.

(A) A lymph node with involuted and partially hyalinised germinal centres (arrow), characteristic of multicentric Castleman’s disease (haematoxylin and eosin stain). (B) Numerous plasmablasts positive for Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) localised to the perifollicular and mantle zone (immunohistochemical staining, original objective magnification 20×).

The plasmablastic variant of multicentric Castleman’s disease is caused by KSHV.2 The disease is characterised by waxing and waning lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly, anaemia, thrombocytopenia, hyponatraemia, hypoalbuminaemia, raised C-reactive protein, and high KSHV viral load. The most widely accepted therapy is rituximab. Chemotherapy can induce remission although it is often transient. We chose etoposide for our patient because of our experience of its use in resource-rich settings, and its availability in Malawi, where rituximab is neither available nor well studied.

High burden of Kaposi sarcoma is widely recognised in sub-Saharan Africa, but multicentric Castleman’s disease is reported surprisingly infrequently. This under-reporting probably reflects underdiagnosis, because it has been described among several recent African immigrants at the National Cancer Institute in the USA.2 Even in African settings where awareness of Kaposi sarcoma is high, familiarity with multicentric Castleman’s disease is low. Histological features can overlap with other diseases such as HIV lymphadenitis, and are challenging to diagnose without KSHV stains, which are often not available in sub-Saharan Africa. A pathology review of lymph nodes from Uganda showed LANA positivity in two of 64 reactive nodes, suggesting multicentric Castleman’s disease.3 A pathology review from South Africa reported many HIV-associated B-cell lymphoproliferations, although neither multicentric Castleman’s disease nor LANA staining were described.4

Our case highlights the need to increase familiarity with multicentric Castleman’s disease among clinicians and pathologists in KSHV-endemic regions, and to develop high-quality diagnostic pathology services throughout sub-Saharan Africa.5 Without such investments, the diversity of KSHV-associated diseases will remain underappreciated. Clinical research collaborations can help to address these limitations and inform care at the individual patient level.

Footnotes

Contributors

SG cared for the patient. YF, NDM, CK, RK, and NGL assisted with staining procedures and pathology review. MKS and DPD tested plasma. All authors contributed to writing the report. Written consent to publish was obtained.

References

- 1.Naresh KN, Raphael M, Ayers L, et al. Lymphomas in sub-Saharan Africa—what can we learn and how can we help in improving diagnosis, managing patients and fostering translational research. Br J Haematol. 2011;154:696–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uldrick TS, Polizzotto MN, Yarchoan R. Recent advances in Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:495–505. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328355e0f3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engels EA, Mbulaiteye SM, Othieno E, et al. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and reactive lymphadenopathy in Uganda. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiggill TM, Mantina H, Willem P, Perner Y, Stevens WS. Changing pattern of lymphoma subgroups at a tertiary academic complex in a high-prevalence HIV setting: a South African perspective. J Acquir Immune Defi c Syndr. 2011;56:460–466. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820bb06a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adesina A, Chumba D, Nelson AM, et al. Improvement of pathology in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:152–157. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]