Supplemental digital content is available in the text.

Key Words: Hormone therapy, Complementary and alternative medicines, Vasomotor symptoms, Menopause, United Kingdom Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening

Abstract

Objective

Given that the Women’s Health Initiative reported in 2002 increased risks of breast cancer and cardiovascular events with hormone therapy (HT) use and many women discontinued use, we assessed the use and perceived efficacy of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) for menopausal symptom relief after discontinuation of HT.

Methods

Postmenopausal women aged 50 to 65 years within the United Kingdom Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening who were willing to take part in a secondary study were mailed a survey to evaluate menopausal symptom management. Use and perceived efficacy of CAMs for relief of vasomotor symptoms (VMS) upon discontinuation of HT were examined.

Results

The survey was sent to 15,000 women between July 2 and July 9, 2008. Seventy-one percent (10,662 of 15,000) responded, and 10,607 women with complete data were included. Ever use of HT was reported by 60.2% (6,383 of 10,607). At survey completion, 79.3% (5,060 of 6,383) had discontinued HT, with 89.7% (4,540 of 5,060) of the latter reporting using one or more CAMs for VMS relief. About 70.4% (3,561 of 5,060) used herbal remedies, with evening primrose oil (48.6%; 2,205 of 4,540) and black cohosh (30.3%;1,377 of 4,540) being most commonly used. Exercise was used by 68.2% (3,098 of 4,540), whereas other behavioral/lifestyle approaches were less frequently reported (13.9%; 629 of 4,540). Contrarily, more women (57%-72%) rated behavioral/lifestyle approaches as effective compared with herbal remedies (28%-46%; rating ≥4 on a “helpfulness” scale from 1-10). Among medical treatments, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were used by 10% and rated effective by 72.1%.

Conclusions

Although more women use over-the-counter medicines, behavioral/lifestyle approaches seem to provide better relief of VMS. There is a pressing need for better evidence-based lay information to support decision-making on CAM use for relief of VMS.

Women may experience significant vasomotor, sexual, psychological, and somatic symptoms during the menopausal transition.1 Vasomotor symptoms (VMS)—hot flushes and night sweats—are the most common,2 with one in two postmenopausal women reporting them to be troublesome.3 A meta-analysis indicated that they often persist several years after menopause,4 compromising quality of life and disrupting women’s sense of well-being.5

Hormone therapy (HT) is the most effective treatment of VMS. It reduces frequency and severity by 75%6 and improves health-related quality of life.7 However, HT use has been in decline since 2002,8 when the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)9 reported increased risks of breast cancer and cardiovascular events in women using HT. This decline has been associated with increasing use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) for relief of menopausal symptoms.10 CAMs are a “diverse group of medical and health care systems, practices and products that are not generally considered to be part of conventional medicine.”11

Although the popularity of CAMs is high among women, there is little evidence to support their use in the control of menopausal symptoms. The efficacy data of herbal remedies and phytoestrogens have so far been inconclusive. Only black cohosh has been investigated systematically in randomized trials, and a Cochrane review has concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support its use.10,12 We report on the use and perceived benefits of CAMs for relief of VMS in women who discontinued HT after the WHI report, using a nested cohort design within the United Kingdom Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS).

METHODS

Study participants

The UKCTOCS is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) assessing the impact of screening on ovarian cancer mortality. Between April 2001 and October 2005, 202,638 apparently healthy postmenopausal women aged 50 to 74 years were recruited to the trial through 13 regional trial centers located in NHS Trusts in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland and randomized to annual screening with (1) serum CA125, interpreted using the “Risk of Ovarian Cancer” algorithm (multimodal group, n = 50,640); (2) transvaginal ultrasound (ultrasound group, n = 50,639); or (3) control (no screening, n = 101,359).13 Postmenopausal status in these women was defined as more than 12 months of amenorrhea after natural menopause or hysterectomy with ovarian conservation or more than 12 months of HT commenced for menopausal symptoms. The study was approved on May 30, 2006 by the Joint University College London/University College London Hospitals Committees on the Ethics of Human Research (Committee A; REC reference 06/Q0505/36).

Survey

At recruitment, all women completed a baseline datasheet regarding reproductive and lifestyle factors and current HT use. Three to 5 years after randomization, the women were sent a postal follow-up questionnaire (FUQ). In addition to lifestyle factors and medical history, the women were asked about their current use of HT. Beginning July 2006, women completing the FUQ were also asked whether they had used any nonhormonal treatments to alleviate menopausal symptoms and if they would be willing to take part in a detailed survey of how women deal with menopause. Women aged 50 to 65 years at FUQ completion who agreed to participate were sent the “managing menopausal symptoms” (MMS) survey. This included questions about any menopausal symptoms they experienced and severity (rated as "bothersome" on a scale from 1 to 10) HT use (ever/current use), reasons for use (eg, hot flushes, vaginal dryness, tiredness), and perceived helpfulness for relief of hot flushes and night sweats. Those who had discontinued HT were asked to select reasons for discontinuation, to list any symptoms they had experienced since stopping (eg, VMS), and if they had used any other therapies/treatments for relieving VMS. The latter were broadly grouped into three categories: (1) herbal/homeopathic remedies or over-the-counter medicines (eg, black cohosh, evening primrose oil, phytoestrogens); (2) behavioral/lifestyle approaches (eg, regular exercise, yoga, counseling, and cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]); or (3) other prescribed medical treatments—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; eg, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs; eg, venlaflaxine), antihypertensive drugs (eg, clonidine), progestogens (eg, megestrol acetate), or antiepileptic drugs (eg, gabapentin). For the purposes of this analysis, CAMs included “herbal/homeopathic remedies or over-the-counter medicines” and “behavioral/lifestyle approaches,” whereas “medical treatments” included all other prescribed treatments. As there have been a number of studies examining the effects of exercise on VMS relief,14,15 we included exercise in behavioral/lifestyle approaches that women may use for relief of menopausal symptoms even though it does not fall strictly under the definition of “CAM.” The women were asked to rate the level of helpfulness with regard to relief of symptoms on a scale from 1 to 10 (1, “no effect”; 10, “most helpful”). For this analysis, treatments were considered to be helpful in relieving VMS if they were rated 7 or higher (most effective) or 4 to 6 (moderately effective) on the “helpfulness” scale (1 to 3 on the scale was considered minimally effective/ineffective).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the results according to HT use, reasons for use of HT, reasons for stopping HT, use of CAMs, and perceived helpfulness of CAMs.

RESULTS

Between July 2 and July 9, 2008, 15,000 UKCTOCS participants aged 50 to 65 years who agreed to participate in the MMS survey were sent the survey. Overall, 10,662 (71.1%) returned the questionnaire. Fifty-five were excluded because of errors in their study reference number (unique identifier). The remaining 10,607 (70.7%) had complete data and were included in the analysis. The baseline characteristics of responders and nonresponders were very similar (Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MENO/A111). The median (interquartile range) age of women at completion of the MMS survey was 59.8 (57.4-61.5) years. Women included in the survey were postmenopausal, as defined in “Methods.”16

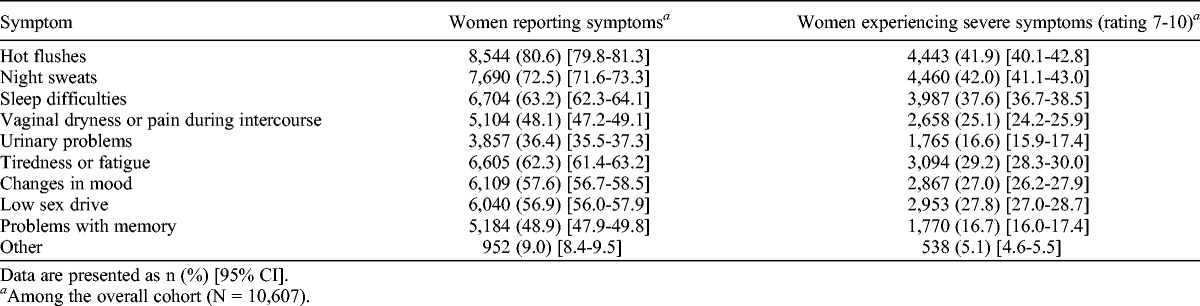

Prevalence and severity of menopausal symptoms

When women were asked about symptoms they had experienced during the menopausal transition (Table 1), most reported hot flushes (80.6%; 8,544 of 10,607) and night sweats (72.5%; 7,690 of 10,607). Severe (≥7) symptoms were reported by almost three quarters (73.5%; 7,795 of 10,607) of women, with the most severe being night sweats (42.0%; 4,460 of 10,607), hot flushes (41.9%; 4,443 of 10,607), sleep difficulties (37.6%; 3,987 of 10,607), and tiredness/fatigue (29.2%; 3,094 of 10,607). Only 1.9% (197 of 10,607) of women reported no symptoms at all.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of menopausal symptoms and severity

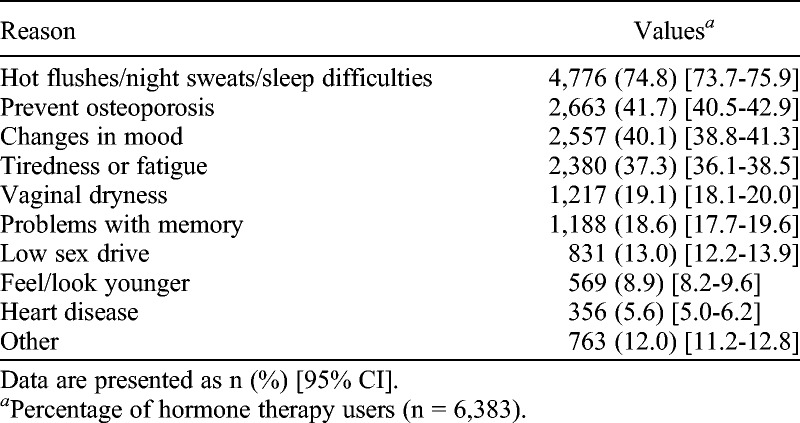

HT use

Overall, 60.2% (6,383 of 10,607) of women reported ever use of HT, of whom 12.3% (1,300 of 10,607) reported that they were still using it at the time of completion of the MMS survey. Of those reporting ever use of HT, 74.8% (4,776 of 6,383) took HT because they experienced hot flushes, night sweats, and sleep difficulties (Table 2). Changes in mood (40.1%; 2,557 of 6,383) and tiredness (37.3%; 2,380 of 6,383) were the other reported indications. Although 41.7% (2,663 of 6,383) included prevention of osteoporosis as a reason for having taken HT, only 3.0% (190 of 6,383) reported it as the sole indication. Most women (71.8%; 4,585 of 6,383) used it for multiple reasons. About 83.7% (5,342 of 6,383) of HT users found it to be helpful.

TABLE 2.

Reasons for taking/having taken hormone therapy

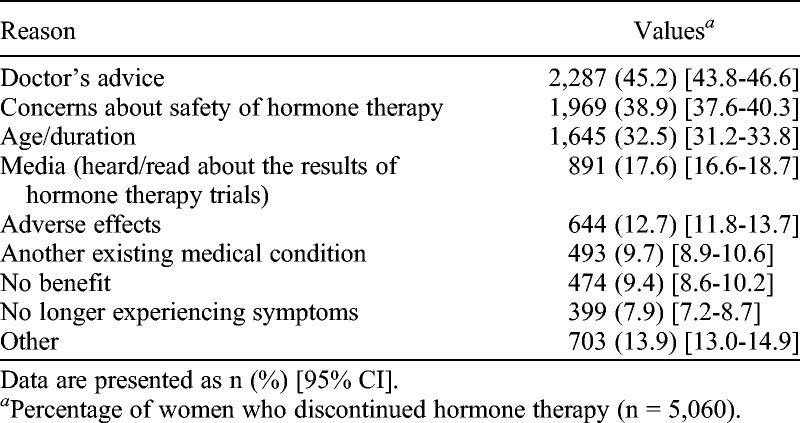

In total, 79.3% (5,060 of 6,383) of HT ever users reported that they had discontinued use. Specifically, 37.5% (2,396 of 6,383) of those younger than 60 years had discontinued use. Over three-quarters (76.7%, 3,883 of 5,060) had discontinued HT because of concerns regarding its safety: doctor’s advice, 45.2% (2,287 of 5,060); personal safety concerns, 38.9% (1,969 of 5,060); or media coverage of HT trials, 17.6% (891 of 5,060; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Reasons for stopping hormone therapy

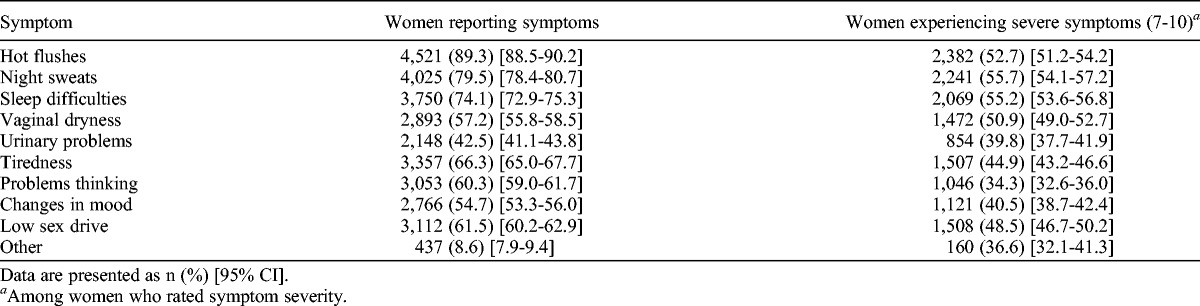

Upon discontinuation of HT, symptoms recurred in 93.1% (4,712 of 5,060) of women, with more than two thirds (67.9%; 3,437 of 5,060) of women reporting severe (≥7) symptoms. The most commonly reported symptoms continued to be hot flushes (89.3%; 4,521 of 5,060), night sweats (79.5%; 4,025 of 5,060), and sleep difficulties (74.1%; 3,750 of 5,060; Table 4). Of the women who discontinued HT, 70.2% were aware that symptoms may recur.

TABLE 4.

Symptoms reported by women stopping hormone therapy

CAMs for relief of VMS in women discontinuing HT

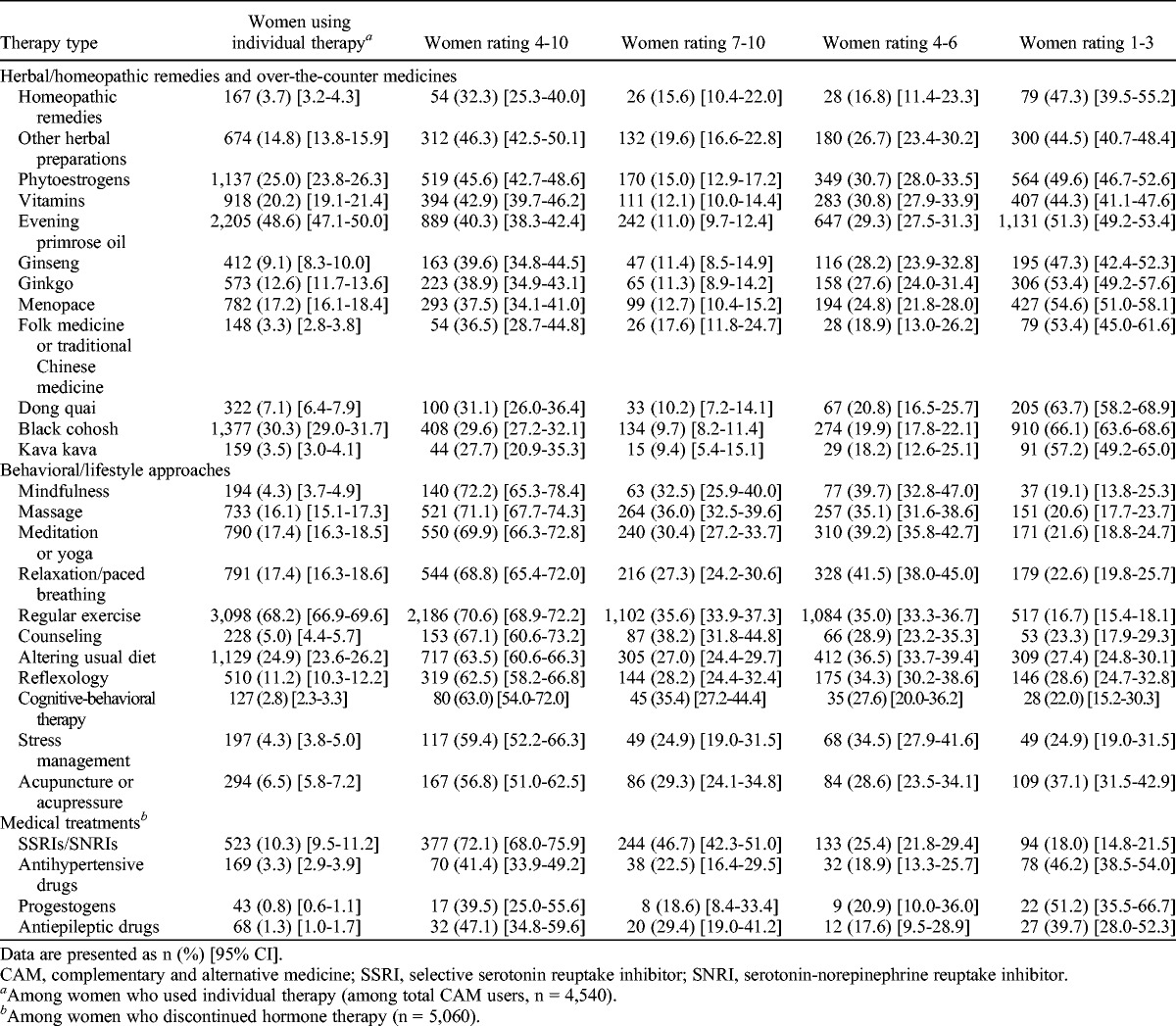

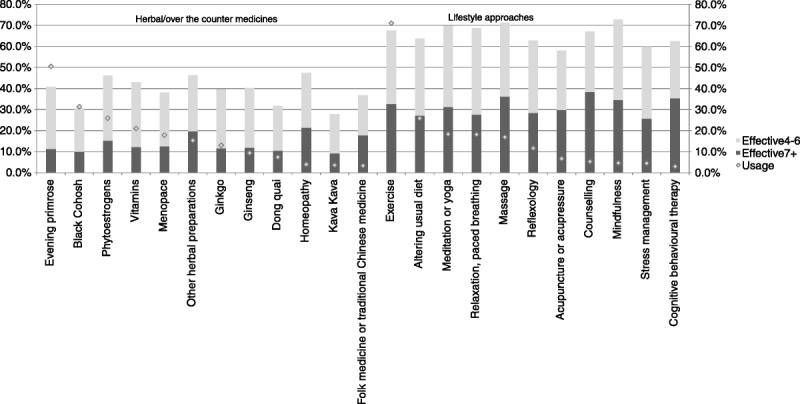

Overall, 42.8% (4,540 of 10,607) of women used CAMs. Of those who had discontinued HT, 89.7% (4,540 of 5,060) reported that they had used one or more CAMs. Use of individual CAMs ranged widely (Fig.), with regular exercise being most commonly used for relief of VMS (68.2%; 3,098 of 4,540; Table 5). Evening primrose oil was the only other option used by half of the women (48.6%; 2,205 of 4,540). Herbal/homeopathic remedies were used by 69.1% (3,495 of 5,060) of the women. Black cohosh (30.3%; 1,377 of 4,540) and phytoestrogens (25.0%; 1,137 of 4,540) were the other two commonly used remedies. Although 72.7% (3,727 of 5,060) used a behavioral/lifestyle approach, usage was low (13.9%; 629 of 4,540) if exercise was excluded. The other main approaches were diet alteration (24.9%; 1,129 of 4,540), meditation/yoga (17.4%; 790 of 4,540), and relaxation/paced breathing (17.4%; 790 of 4,540). Only 17.9% (813 of 4,540) used herbal/homeopathic remedies exclusively, and 23.0% (1,045 of 4,540) used only behavioral/lifestyle approaches.

TABLE 5.

Use and perceived effectiveness of CAMs (herbal/homeopathic remedies and over-the-counter medicines or behavioral/lifestyle approaches) or medical treatments in menopausal symptom relief by women who have stopped using hormone therapy

FIG.

Use and perceived efficacy of complementary and alternative medicine in menopausal symptom relief.

We further assessed whether patterns of CAM use differed by age by subdividing the cohort into two groups: women younger than the median age of 59.8 years and women older than 59.8 years. Women who were older than 59.8 years at survey completion reported higher use of all CAMs, except for Menopace (Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MENO/A112).

Use of multiple CAM therapies

Overall, 58.6% of women used up to three CAM therapies, with 22.0% (999 of 4,540) using one CAM therapy, 18.9% (883 of 4,540) using two CAM therapies, and 58.5% (2,658 of 4,540) using three or more CAM therapies (Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MENO/A111). The latter included 39.0% (1,362 of 3,492) using three or more herbal remedies and 29.5% (1,100 of 3,727) using three or more lifestyle approaches.

Self-reported effectiveness

All behavioral/lifestyle approaches were rated to be effective by at least half of the women (rating ≥4; Table 5), with more than two thirds of those who had used mindfulness (72.2%; 140 of 194), massage (71.1%; 521 of 733), meditation/yoga (69.9%; 550 of 790), relaxation (68.8%; 544 of 791), regular exercise (70.6%; 2,186 of 3,098), or counseling (67.1%; 153 of 228) reporting it to be effective in relieving VMS. In contrast, all herbal/homeopathic remedies were rated effective by less than half of the women who used them. Of these, the highest ratings were for other herbal preparations (46.3%; 312 of 674), phytoestrogens (45.6%; 519 of 1,137), and vitamins (42.9%; 394 of 918). About 40.3% (889 of 2,205) of women using evening primrose oil and 29.6% (408 of 1,377) of women using black cohosh reported them to be useful.

Recommend use of CAMs to other women

Of those who used CAM remedies, few would recommend their use to other women. The most recommended CAMs were phytoestrogens (16.5%; 188 of 1,137) and evening primrose oil (11.0%; 242 of 2,205), followed by black cohosh (8.0%; 110 of 1,377; data not shown).

Medical treatments for relieving VMS in women discontinuing HT

Women were also asked whether they had used any other medical treatments (SSRIs, SNRIs, antihypertensive drugs, progestogens, or antiepileptic drugs). Overall, 13.8% (697 of 5,060) of women used one or more medical treatments for relief of VMS; SSRIs, in particular, were used by 10.3% (523 of 5,060), of whom almost three quarters (72.1%; 377 of 523) found them helpful.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is, to date, the largest study of CAM use in women who have discontinued HT. We are aware of only one other study (based on data from 563 women) that specifically explored CAM use in this population.17 Our 2008-2009 cross-sectional survey of more than 10,000 British postmenopausal women aged 54 to 65 years showed that most (93.1%) of the women who discontinued HT experienced recurrence of symptoms, with three out of four women reporting severe (rating ≥7) symptoms. About 89.7% used CAMs, with most opting for herbal/homeopathic remedies. Importantly, although behavioral/lifestyle approaches, excluding exercise, were used by only 13.9% of women, these were reported to be more effective than herbal/homeopathic remedies. More than two thirds of those who had used mindfulness, massage, meditation/yoga, relaxation, and counseling reported them to be effective (score ≥4), compared with less than half of the women using herbal/homeopathic remedies. In keeping with this, few women would recommend use of herbal/homeopathic remedies to others for relief of menopausal symptoms. The data suggest a disconnect between women’s use of herbal/lifestyle CAMs and women’s perceptions of their effectiveness after having used them.

In our study, 60% of women reported ever use of HT, similar to the 47.2% reported in the Million Women Study.18 Most women had used it for multiple reasons, with hot flushes/night sweats (74.8%) being the leading indication. Most (84%) found it helpful for relief of menopausal symptoms, but most (80%) discontinued use, including 37% of women younger than 60 years. The main reasons were doctor’s advice, safety concerns, and having heard/read about the results of HT trials. Recently, a Norwegian study also reported on reasons for stopping HT, with 30% of women discontinuing use because of fear of adverse events,19 similar to the 39% of women in our study reporting this as the main reason. Three out of four women were aware that their symptoms would recur, and over 90% reported recurrence of symptoms upon discontinuing HT, as also reported by the Norwegian study.19 Until June 2013, guidelines on HT use had recommended that women use HT for the shortest time possible. Despite guidelines now approving the use of HT for VMS up to age 60 years,20 the impact of the original negative publicity is likely to be long-lasting.

The overall prevalence of CAM use in 2008-2009 (42.8%) in this study is comparable to that (48%) reported on in a meta-analysis in a recent systematic review of CAM surveys.21 Small differences may be attributable to overrepresentation of US women in the latter and inclusion of studies before the publication of the WHI results in 2002.

Herbal medicine (black cohosh, donq quai, and evening primrose), soy/phytoestrogens (including red clover), relaxation, and yoga were the most commonly used CAMs for menopausal symptom relief in the recent systematic review.21 Half of the women surveyed reported use of herbal remedies, with evening primrose oil (48.6%), black cohosh (30.3%), and phytoestrogens (25.0%) being most commonly used. However, these were deemed effective (scores ≥4) in relieving symptoms by less than half of the women surveyed. Despite a third of the women using black cohosh, more than two thirds reported minimal effectiveness. Although many used herbal/homeopathic remedies, few (phytoestrogens, 16.5%; evening primrose oil, 11.0%; black cohosh, 8.0%) would recommend these to other women.

Interestingly, nearly three quarters of the women reported use of exercise as the approach of choice, with symptom relief in 70%. The other lifestyle approaches, although used by fewer women, were perceived as more effective than herbal remedies. Interestingly, RCTs have not confirmed exercise to be effective in alleviating VMS15,22 but have reported that it may improve sleep and depression in postmenopausal women.14 Mindfulness has been shown to reduce distress and bother from VMS compared with a wait-list control in an RCT.23 Furthermore, a recent prospective cohort study of 6,040 women comparing two diet methods found Mediterranean-style diet to be associated with fewer VMS.24 The treatments women reported to be most effective (scores ≥7) were counseling (38%), massage (36%), and CBT (35%), consistent with previous findings suggesting that psychoeducational interventions alleviate VMS.25 A recent RCT showed that CBT significantly reduces problem ratings associated with VMS and the frequency of night sweats26 and that CBT can be delivered with little health professional time.27 Furthermore, CBT, whether delivered in a group or in self-help format, is effective in reducing the impact of VMS.28

In our study, few women used medical treatments other than HT to relieve their VMS, with only 10% having used SSRIs/SNRIs and with less than 5% having used antihypertensive drugs, progestogen, or antiepileptic drugs. SSRIs have consistently been reported, although with lower efficacy than HT, to reduce the frequency and severity of VMS in RCTs.29-31 Seventy-two percent of women in our survey also reported SSRIs to be effective, with almost half reporting them to be very effective (scores ≥7). Many women use CAMs to alleviate menopausal symptoms, as there is a perception that CAMs are safer and more “natural” than HT. A recent review indicated that 55% of women using CAMs did not disclose this to their medical practitioner21 even though potentially life-threatening adverse events, such as hepatitis and liver failure, have been reported with use of black cohosh.32

Many women seek over-the-counter CAMs for menopausal symptom relief. The discrepancy between women’s choice of strategies, their perceptions of outcomes, and the current evidence suggests that they would benefit from evidence-based information about the efficacy of these interventions. An earlier US survey of 413 women also suggested that women do not feel sufficiently informed to make decisions regarding CAM options for alleviating menopausal symptoms.33 A UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance on the effectiveness of menopausal treatments, which is scheduled to be published in 2015, is therefore most timely.

The main strengths of this study are its size, generalizability (postmenopausal women from the general population across England, Wales, and Northern Ireland), and the survey period 2008-2009, after the main WHI results9 but before data reanalysis.34 We add to previous UK surveys that reported CAM use between 2001 and 2006. As all women had previously used HT, we believe that the efficacy of HT provided them a useful reference for evaluating the effectiveness of CAMs in relieving VMS. We also asked women which CAMs they would recommend to other women, which we thought was a good indicator of their overall experience with CAM use. Our study is in keeping with most other studies that focused on relief of vasomotor menopausal symptoms, which women find the most distressing. There is currently a lack of evidence for management strategies for menopausal symptoms in women who have discontinued HT, and our study may provide useful guidance/information regarding the use of alternative therapies for symptom relief. As Espen Gjelsvik et al19 indicated, despite experiencing significant VMS, women tend to prefer to live without HT, suggesting that women are still concerned about the safety and adverse events associated with HT use.

Limitations include the cross-sectional design of the study and the possibility that the women who took part in the MMS survey may have been more likely to have severe menopausal symptoms and therefore more likely to try various treatment modalities. In keeping with all previous surveys, there is inherent bias related to self-selection. There is a possibility of recall bias. In addition, it is probable that women who had troublesome (>7) symptoms were more likely to have completed the survey. However, the prevalence of self-reported severe symptoms (73.5%) in our study is in keeping with previous reports.35 Our questionnaire did not collect data on exact formulation, dose, adverse events related to CAM use, or concurrent use of multiple CAM treatments. The survey included an exhaustive list of CAM therapies. There may be newer therapies for VMS relief that women may have tried since. The participants were mainly white; therefore, we are unable to report on use among other ethnic groups. We did not examine the relationship between HT/CAM use and variables such as education, income, and smoking, which have previously been shown to influence a woman’s decision-making regarding uptake of these therapies.

CONCLUSIONS

Although more women use over-the-counter medicines, they report behavioral/lifestyle approaches to be more effective in alleviating VMS. This suggests the need for more readily available evidence-based information to support women’s decision-making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to the women throughout the UK who participated in the trial and to the entire medical, nursing, and administrative staff who worked on the UKCTOCS.

Footnotes

M.S.H. and U.M. contributed equally to this work.

U.M., A.G.-M., M.S.H., L.F., and A.L. were involved in study design and concept. U.M., A.G.-M., C.K., and C.G. performed the literature search, drafted the manuscript, and prepared the tables. U.M., A.G.-M., and M.B. performed statistical analysis. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version. U.M. is the guarantor.

The funding source or sponsor had no role in data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The researchers are independent of the funders.

Funding/support: The trial was core-funded by the Medical Research Council, Cancer Research UK, and the Department of Health (with additional support from the Eve Appeal, Special Trustees of Bart’s and the London, and Special Trustees of University College London Hospitals) and supported by researchers at the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Center.

Clinical trial registration: ISRCTN22488978.

Financial disclosure/conflicts of interest: I.J. has a consultancy arrangement with Becton Dickinson in the fields of tumor markers and ovarian cancer. U.M. has financial interest, through University College London Business and Abcodia Ltd, in the third-party exploitation of clinical trials biobanks, which have been developed through research at University College London. None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest, relationships, or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Website (www.menopause.org).

REFERENCES

- 1. Mishra GD, Kuh D. Health symptoms during midlife in relation to menopausal transition: British prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012; 344: e402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Palacios S, Henderson VW, Siseles N, Tan D, Villaseca P. Age of menopause and impact of climacteric symptoms by geographical region. Climacteric 2010; 13: 419- 428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moilanen J, Aalto AM, Hemminki E, Aro AR, Raitanen J, Luoto R. Prevalence of menopause symptoms and their association with lifestyle among Finnish middle-aged women. Maturitas 2010; 67: 368- 374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Politi MC, Schleinitz MD, Col NF. Revisiting the duration of vasomotor symptoms of menopause: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23: 1507- 1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daly E, Gray A, Barlow D, McPherson K, Roche M, Vessey M. Measuring the impact of menopausal symptoms on quality of life. BMJ 1993; 307: 836- 840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maclennan AH, Broadbent JL, Lester S, Moore V. Oral oestrogen and combined oestrogen/progestogen therapy versus placebo for hot flushes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; CD002978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Welton AJ, Vickers MR, Kim J, et al. Health related quality of life after combined hormone replacement therapy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008; 337: a1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Menon U, Burnell M, Sharma A, et al. Decline in use of hormone therapy among postmenopausal women in the United Kingdom. Menopause 2007; 14(pt 1): 462- 467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 321- 333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borrelli F, Ernst E. Alternative and complementary therapies for the menopause. Maturitas 2010; 66: 333- 343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine at the National Institutes of Health. Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? Available at: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/ Accessed July 3, 2014.

- 12. Leach MJ, Moore V. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga spp.) for menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 9: CD007244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ryan A, et al. Recruitment to multicentre trials—lessons from UKCTOCS: descriptive study. BMJ 2008; 337: a2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sternfeld B, Guthrie KA, Ensrud KE, et al. Efficacy of exercise for menopausal symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Menopause 2014; 21: 330- 338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Daley A, Stokes-Lampard H, MacArthur C. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; CD006108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hunter MS, Gentry-Maharaj A, Ryan A, et al. Prevalence, frequency and problem rating of hot flushes persist in older postmenopausal women: impact of age, body mass index, hysterectomy, hormone therapy use, lifestyle and mood in a cross-sectional cohort study of 10,418 British women aged 54-65. BJOG 2012; 119: 40- 50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kupferer EM, Dormire SL, Becker H. Complementary and alternative medicine use for vasomotor symptoms among women who have discontinued hormone therapy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2009; 38: 50- 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Million Women Study Collaborative Group. The Million Women Study: design and characteristics of the study population. The Million Women Study Collaborative Group. Breast Cancer Res 1999; 1: 73- 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Espen Gjelsvik B, Straand J, Hunskaar S, Dalen I, Rosvold EO. Use and discontinued use of menopausal hormone therapy by healthy women in Norway: the Hordaland Women’s Cohort study. Menopause 2014; 21: 459- 468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Panay N, Hamoda H, Arya R, Savvas M. The 2013 British Menopause Society & Women’s Health Concern recommendations on hormone replacement therapy. Menopause Int 2013; 19: 59- 68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Posadzki P, Lee MS, Moon TW, Choi TY, Park TY, Ernst E. Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by menopausal women: a systematic review of surveys. Maturitas 2013; 75: 34- 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reed SD, Guthrie KA, Newton KM, et al. Menopausal quality of life: RCT of yoga, exercise, and ω-3 supplements. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014; 210: 244.e1- 244.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carmody JF, Crawford S, Salmoirago-Blotcher E, Leung K, Churchill L, Olendzki N. Mindfulness training for coping with hot flashes: results of a randomized trial. Menopause 2011; 18: 611- 620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Herber-Gast GC, Mishra GD. Fruit, Mediterranean-style, and high-fat and -sugar diets are associated with the risk of night sweats and hot flushes in midlife: results from a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 2013; 97: 1092- 1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tremblay A, Sheeran L, Aranda SK. Psychoeducational interventions to alleviate hot flashes: a systematic review. Menopause 2008; 15: 193- 202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ayers B, Smith M, Hellier J, Mann E, Hunter MS. Effectiveness of group and self-help cognitive behavior therapy in reducing problematic menopausal hot flushes and night sweats (MENOS 2): a randomized controlled trial. Menopause 2012; 19: 749- 759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stefanopoulou E, Hunter MS. Telephone-guided Self-Help Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for menopausal symptoms. Maturitas 2014; 77: 73- 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Norton S, Chilcot J, Hunter MS. Cognitive-behavior therapy for menopausal symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats): moderators and mediators of treatment effects. Menopause 2014; 21: 574- 578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barton DL, LaVasseur BI, Sloan JA, et al. Phase III, placebo-controlled trial of three doses of citalopram for the treatment of hot flashes: NCCTG trial N05C9. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 3278- 3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2006; 295: 2057- 2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med 2013: 1- 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joy D, Joy J, Duane P. Black cohosh: a cause of abnormal postmenopausal liver function tests. Climacteric 2008;11:84-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Armitage GD, Suter E, Verhoef MJ, Bockmuehl C, Bobey M. Women’s needs for CAM information to manage menopausal symptoms. Climacteric 2007; 10: 215- 224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2013; 310: 1353- 1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Keenan NL, Mark S, Fugh-Berman A, Browne D, Kaczmarczyk J, Hunter C. Severity of menopausal symptoms and use of both conventional and complementary/alternative therapies. Menopause 2003; 10: 507- 515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.