Abstract

Noninvasive in vivo quantitation of boron is necessary for obtaining pharmacokinetic data on candidate boronated delivery agents developed for boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT). Such data, in turn, would facilitate the optimization of the temporal sequence of boronated drug infusion and neutron irradiation. Current approaches to obtaining such pharmacokinetic data include: positron emission tomography employing F-18 labeled boronated delivery agents (e.g., p-boronophenylalanine), ex vivo neutron activation analysis of blood (and very occasionally tissue) samples, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques. In general, NMR approaches have been hindered by very poor signal to noise achieved due to the large quadrupole moments of B-10 and B-11 and (in the case of B-10) very low gyromagnetic ratio, combined with low physiological concentrations of these isotopes under clinical conditions. This preliminary study examines the feasibility of proton NMR spectroscopy for such applications. We have utilized proton NMR spectroscopy to investigate the detectability of p-boronophenylalanine fructose (BPA-f) at typical physiological concentrations encountered in BNCT. BPA-f is one of the two boron delivery agents currently undergoing clinical phase-I/II trials in the U.S., Japan, and Europe. This study includes high-resolution 1H spectroscopic characterization of BPA-f to identify useful spectral features for purposes of detection and quantification. The study examines potential interferences, demonstrates a linear NMR signal response with concentration, and presents BPA NMR spectra in ex vivo blood samples and in vivo brain tissues.

Keywords: proton NMR, BPA, BNCT, boron, pharmacokinetics

I. INTRODUCTION

Boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) is an experimental treatment method for cancer in which B-10 labeled substances, such as 1,boronophenylalanine fructose (1, BPA-f) or sodium borocaptate (BSH), are intravenously infused and the local area of tumor exposed to thermal or epithermal neutron irradiation.1 The success of the BNCT treatment is predicated on sufficient amounts of the B-10 label being incorporated into tumor or its afferent microvasculature concomitantly with lower amounts being incorporated into normal tissues and blood. The alpha and lithium-7 particles released upon neutron capture by B-10 have a very short range (approximately 5–10μ), a high linear energy transfer (LET), and an oxygen enhancement ratio (OER) close to unity. The first of these nuclear properties ensures that most of the radiation dose is confined within the B-10 containing cells; the second and third render the biological response relatively insensitive to temporal delivery factors and to the cellular oxygenation state. Thus, with the proper fluence of neutrons delivered to the target tissues the radiation dose to tumor cells should be adequate to cause cytotoxicity while that to normal tissues should be within their tolerance range.

To optimize the delivery of BNCT, it is very useful to be able to measure the concentration of B-10 (or its carrier molecule) during and following its intravenous infusion.2 Currently, our protocol involves periodic central venous blood sampling followed by ex vivo assay of B-10 concentration by prompt-gamma neutron activation analysis (PGNAA).3,4 This method, although highly accurate, is invasive and does not provide corresponding B-10 concentration kinetics in normal brain and brain tumor. The use of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) as a potential noninvasive technique for studying the pharmacokinetics of boronated delivery agents in BNCT has previously been proposed.5–8 The studies cited have attempted to directly measure the concentrations of boron in biological tissues. Although naturally occurring boron is isotopically composed of approximately 20% B-10 and 80% B-11, the boron that is employed for actual BNCT studies is, typically, >98% isotopically enriched in B-10. B-10 has a nuclear magnetic spin of 3 and a gyromagnetic ratio of 4.6 MHz/T. Its large quadrupole moment produces such large line broadening in NMR that B-10, with a relative NMR sensitivity of 0.02 compared to 1H, has to be detected by nonconventional NMR techniques.5 The proton–boron double-resonance measurement requires dual radiofrequencies (rf) channel operation, sophisticated acquisition scheme, and parameter control as well as potentially high rf power deposition resulting from the massive signal averages at very short repetition time.5 These factors hinder the potential clinical application of the double-resonance technique. B-11, on the other hand, has a spin of 3/2 and a gyromagnetic ratio of 13.7 MHz/T. Although the line-broadening phenomenon is still problematic for the satellite transitions between ±3/2→±1/2, the measurement of the boronated delivery agents BSH and BPA (containing naturally occurring boron) has been successfully demonstrated at the upper end of the typical range of physiological concentrations by observing the central transition −1/2→+1/2. If the measurement of boron as reported were to be made using the same delivery agents that are actually employed for BNCT therapy (i.e., >98% isotopically enriched in B-10), the method would have insufficient sensitivity to be useful.

We have taken a different approach to this problem. Rather than attempting to detect boron, we have explored the possibility of employing proton NMR to detect the protons associated with the B-10 carrier molecule BPA which contains aromatic and other protons (Fig. 1). Based on experimental preparation, we have identified a specific proton NMR signature produced by BPA and examined potential interferences from other biomolecules. As a preliminary test, we examined this signal in whole blood samples and in vivo brain tissues of patients undergoing BNCT. The present communication describes our preliminary investigation.

Fig. 1.

Molecular structure of p-boronophenylalanine (BPA).

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. Materials used

1. BPA/D2O phantom

To determine all proton spectral features of BPA and the correlation between the NMR measurement and concentration, several samples of BPA at various concentrations were prepared. B-10-enriched BPA (Boron Biologicals, Inc., Raleigh, NC) was dissolved in deuterium oxide (D2O) at concentrations of 0.3, 0.8, 2.3, 3.1, 4.7, and 9.3 mM. When complete dissolution of the BPA proved difficult to achieve, Na2CO3 was added to adjust the pH to approximately 9 and thereby promote full dissolution.

2. BPA-f phantom

Since fructose forms a complex with BPA which has a higher solubility than BPA, BPA fructose is typically used for patient infusions. To evaluate the effect of fructose on the proton spectrum of BPA, we acquired spectra from fructose and BPA-fructose complex. A BPA-fructose (BPA-f) phantom was prepared by dissolving 145 mM BPA with equal molar concentration of D-fructose (assay >99%, Fluka Chemie AG, Switzerland) in H2O.

3. Tyrosine

Tyrosine is a likely metabolite of BPA in the event of the B-10 interacting with the neutron and transforming into Li-7 and the aromatic ring remaining intact in BNCT. In order to understand any potential interference from its presence, we have obtained its NMR spectra to compare with that of BPA. A tyrosine (HPLC grade, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis) aqueous phantom was made by dissolving ~3×103 μg/ml in 5% acetic acid aqueous solution, corresponding to the tyrosine concentration of ~16 mM.

4. Brain metabolite phantom

To examine the visibility of BPA in the presence of typical brain metabolites, 12 mM each of NAA, creatine, lactic acid, myoinositol, and 1.6 mM of BPA were dissolved in H2O. The concentration of NAA was consistent with reported typical values while those of lactic acid and myoinositol are probably somewhat higher.9 No additional pH adjustments were needed for the complete dissolution of BPA.

5. Human blood sample

To test the feasibility of observing the BPA NMR signature in biological material, human blood samples (approximately 2 ml each) were collected from patients undergoing BNCT using a Vacutainer with a sterile interior, containing 0.050 ml 15% EDTA solution (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), prior to and 60 min following a 250 mg/kg BPA-f intravenous infusion. Prior to NMR measurements the boron content of the blood samples was measured by prompt-gamma neutron activation analysis and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES),3,4 and determined to be 34±2 μg B-10/ml blood.

6. In vivo brain tissue

Informed consent was obtained from two patients with intracranial melanoma metastases having completed their BNCT 6–8 h post the BPA-f infusion. The boron content of the blood samples at the time of magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) measurements was determined to be 10±2 μg B-10/ml by PGNAA, through which the tumor concentration of BPA was estimated to be about 35 μg/ml.

B. NMR measurements

1. Aqueous phantoms

For the water-based phantoms containing BPA and/or fructose with or without brain metabolites, proton NMR spectra were acquired using a 360 MHz (8.4 T) vertical bore spectrometer (Bruker Instruments, Billerica, MA) and a 5 mm probe. Data were collected from approximately 0.3 ml aliquots of each sample contained in a 5 mm NMR tube. Water suppression was performed using a 400 ms radiofrequency pulse centered at water resonance frequency prior to a 4 μs (approximately 15°) pulse for free-induction decay (FID) collections. Other acquisition parameters were: 32 averages; repetition time (TR): 2s; spectral size: 1024; and spectral width: 3.6 kHz. Data processing included apodization (6 Hz Gaussian broadening), zero filling, Fourier transformation, and manual zero-order phasing.

2. Human blood sample

The proton NMR spectra were acquired from approximately 0.3 ml aliquots of the patient whole blood samples in 5 mm NMR tubes using a water presuppression spin-echo technique. Spin echo instead of FID was used in order to suppress broader background signals primarily due to the presence of macromolecules and reduce the base-line distortion. A 200 ms rf pulse was used to presuppress the water resonance and the spin echo was generated by a pair of 4 μs rf pulses with echo time (TE) of 6 ms, TR 2 s, 64 averages, spectral size 1024, and spectral width 3.6 kHz, and the same spectral processing as described above.

3. In vivo brain tissues

The proton spectra of the brain tumor and normal brain regions were acquired using a STEAM sequence in conjunction with water presaturation on a 1.5 T whole body MR scanner with a standard head coil (Vision, Siemens Med. Sys. AG, Erlangen, Germany). Acquisition parameters were TE 30 ms, voxel size 2×1.7×1.6 cm3, TR 1.5 s, and 128 averages for a total acquisition time of 3.3 min/spectrum.

III. RESULTS

As shown in Fig. 1, BPA contains two types of magnetically equivalent aromatic protons, Ha and Hb, leading to two distinct resonances at 7.1 and 7.4 ppm, referenced to the proton resonance frequency of sodium 3-(trimethylsilyl)propanesulfonate (TMS), in the BPA NMR spectrum [Fig. 2(a)]. The other observed proton resonances can be attributed to protons marked Hc-e. The –CH– protons resonate at 3.4 ppm and the benzylic –CH2– protons at 2.9 and 2.7 ppm. Residual of the water resonance appears at ~4.7 ppm and a weak signal at 4.1 ppm may be related to NH2.

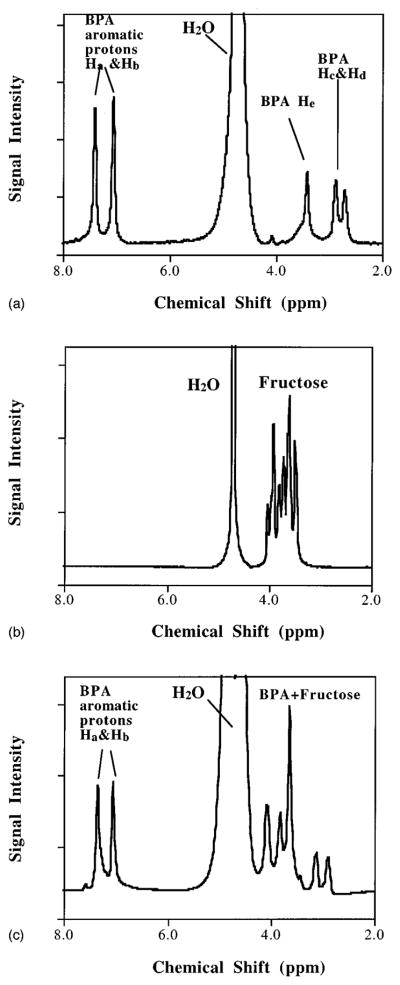

Fig. 2.

(a) A proton NMR spectrum of 31 μg BPA/g D2O (corresponding to 3.1 mM) solution. (b) Proton spectrum of 12 mM fructose D2O solution. (c) Proton spectrum of BPA-fructose aqueous solution.

Figure 2(b) shows the NMR spectrum of fructose in D2O. Proton resonances of fructose spread between approximately 4.1 and 3.4 ppm, overlapping the BPA–CH– resonances. Residual of the water resonance appears at ~4.7 ppm. Figure 2(c) shows the proton NMR spectrum of BPA-f in H2O. The proton spectrum shows BPA proton resonance peaks at 7.1–7.4 and at 2–3 ppm without interference from fructose, and at 3–4 ppm in superposition with fructose proton resonance. This is consistent with the superposition of individual spectral features observed in Figs. 2(a) and 2(b).

Figure 3 shows the results of the incremental BPA concentration experiment. The integration of the aromatic doublet NMR proton resonance signals correlated excellently (r2=0.997) with the known (i.e., independently measured by PGNAA) BPA concentrations in the range of 0.3–10 mM. Tiss and Tum represent the range of typical BPA concentrations observed in normal tissues and tumors, respectively.10,11 Integrated signals were normalized to that of 0.3 mM BPA and 1 mM BPA corresponds to 10 ppm B-10.

Fig. 3.

Integration of the peak areas of the BPA aromatic doublet Ha and Hb (7.1 and 7.4 ppm) vs BPA concentration.

Figure 4 shows the molecular structure of tyrosine, a likely BPA metabolite when B-10 transforms into Li-7 and the aromatic ring remains intact during BNCT. Figure 4(b) shows a proton spectrum of the tyrosine aqueous solution. As expected from the intact aromatic ring, we observe the doublet feature downfield from the water resonance. However, the exact chemical shifts are slightly different from those of BPA. The aromatic peaks can be located at 6.7 and 7.0 ppm (compared to 7.1 and 7.4 ppm for BPA), probably due to more electron shielding from –OH compared to –B(OH)2 in BPA. Also –CH– is shifted from 3.4 to 3.9 ppm and –CH2 appears at 2.9 and 3.1 ppm, respectively. This indicates that proton NMR can potentially distinguish BPA from tyrosine, a possible interfering metabolite, if present at comparable concentrations. Although the –CH– and –CH2– can potentially be used to distinguish BPA from tyrosine in a high-resolution NMR spectrum, those signals are probably obscured by in vivo metabolite signals.

Fig. 4.

(a) Molecular structure of tyrosine. The molecule contains two types of magnetic-equivalent aromatic protons, the same as in BPA, leading to the distinctive aromatic resonances downfield from the water resonance (b). (b) A proton NMR spectrum of the tyrosine aqueous solution. Aromatic protons are at 6.7 and 7.0 ppm. –CH– at 3.9 ppm and –CH2– at 3.0 and 2.9 ppm.

Figure 5 shows the NMR resonance spectrum acquired from the brain metabolite phantom. The aromatic doublet due to BPA is clearly visible at 7.1–7.4 ppm. Although NMR resonance signals from the brain metabolites (most likely from the –NH– groups) can be seen at 6.6 and 8.0 ppm, there is no overlap with the aromatic proton resonance from BPA. However, the BPA NMR spectral characteristics between 4.1 and 2.7 ppm are totally obscured by signals from the brain metabolites. Integration of the BPA aromatic proton peak area in comparison with three NAA protons (1.95 ppm, just out of range in Fig. 5) indicated that the BPA concentration was about 1.7±0.3 mM, which is consistent with the concentration of BPA relative to other brain metabolites in the preparation.

Fig. 5.

Proton spectrum of BPA in a phantom of BPA+brain metabolites. Note the NAA CH3 signal (1.95 ppm) is just out of range in this figure.

Figure 6 shows portions of the proton spectra of the patient whole blood pre- and post- and BPA-f infusion in the frequency range of 6–9.6 ppm. In the chemical shift range of 1–4.5 ppm, the spectral window was filled with multiple signals from various metabolites, lipids, and macromolecules. Comparing pre- and post-BPA-f infusion blood spectra, in the spectral window of approximately 6–8 ppm, only the BPA aromatic doublet appears in the postinfusion spectrum at 7.0–7.3 ppm with no apparent interfering signals in the preinfusion spectrum. The aromatic doublet has a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of approximately 4:1 for a boron concentration of 34 μg B-10/g, corresponding to 3.4 mM BPA concentration.

Fig. 6.

Proton spectra of whole blood samples from a BNCT patient pre-BPA-f infusion (a) and post-BPA-f infusion (b).

Figure 7 shows one of the typical proton spectra acquired from a 2×1.7×1.6 cm3 voxel placed over the left frontal melanoma metastasis (a) and normal tissue (b) in a BNCT patient’s brain on a 1.5 T clinical NMR scanner. The spectrum [Fig. 7(a)] clearly shows the aromatic doublet at 7.2–7.5 ppm (SNR ~2:1) in the tumor even 8 h post the BPA-f infusion with only 3 min signal averages over a tissue sampling volume of 5.4 cm3. The BPA aromatic signals in the normal brain tissues were too weak to be positively identified.

Fig. 7.

Portion of the proton spectra of brain tissue of a melanoma patient underwent BNCT over the tumor region (a) and normal tissue region (b). The aromatic signals are clearly identified at the tumor region while the aromatic signals were too weak to be positively identified in the normal tissue.

IV. DISCUSSION

For in vivo detection of exogenously administered agents by NMR it is desirable that the spectral features of these agents be sufficiently strong for detection with reasonable numbers of signal averages and not be obscured by native or endogenous spectral features. Although one can identify several characteristic resonances in the proton spectrum of BPA in the range of 2.7–7.4 ppm, the aromatic doublet at 7.1 and 7.4 ppm have been specifically identified as being well suited for NMR quantitation of BPA in vivo due to a lack of interference from other endogenous and exogenous sources, as well as immunity from interference from the water suppression process. Small differences in spectral line positions (on the order of 0.03–0.05 ppm) observed in the NMR spectra obtained from BPA in D2O, BPA fructose, and the BPA brain metabolite phantom, may actually reflect the small variations in chemical environments as BPA forms complexes with fructose or components of brain metabolites.12 The other BPA NMR signals between 2 and 4 ppm are essentially obscured by natively present brain metabolite signals9,13–15 and by the fructose complex introduced with the BPA (see Figs. 2–5). The spectrum obtained from the BPA-brain metabolite phantom demonstrates that in addition to BPA aromatic protons there are signals, probably –NH–, in the region of 6.5–8.0 ppm. This observation is consistent with previous reports. The signals are most likely due to exchangeable protons and can be severely attenuated due to saturation transfer from water magnetization.13,14 Our data obtained from the blood samples of the BNCT study patients confirm that these aromatic signals are not subject to interference under usual experimental conditions. The amount of tyrosine or other aromatic species, if present, are below the detectable level [Fig. 6(a)]. The separation of this doublet structure from the rest of the NMR spectrum makes it amenable to selective excitation, which would be of particular significance if biodistribution of BPA were to be measured in the future by means of spectroscopic imaging techniques.

The measurements at 8.4 T indicated that the aromatic doublet was a useful spectral signature for BPA detection and it was tested in whole blood samples (see Fig. 6). Detection of BPA in vivo at 1.5 T (the field strength of most clinical imagers) about 8 h post BPA-f infusion confirmed that single voxel MRS can potentially be used to measured BPA in vivo at the clinical dose for BNCT patients. Typically, BPA uptake in tumor is 3–4 fold higher than in blood.10,11 The 1 mM of B-10 in the blood sample suggests that the concomitant BPA concentration in tumor is about 3.5 mM at the time of the MRS scanning. The peak concentration of BPA in tumor during or shortly after the BPA-f infusion may reach as high as 10 mM since its concentration in blood could reach 3.4 mM in clinical BNCT. Therefore, the SNR for a 3 min signal average should be much better than 2:1 observed in this preliminary study if the measurement were conducted during and shortly post BPA-f infusion, the time window one is interested in clinical BNCT, on a 1.5 T clinical imager over a voxel of 8 cm3 in tumor.

Recently, aromatic proton signals have also been utilized for in vivo detection of orally administered phenylalanine in the brain of phenylketonuria (PKU) patients at a dose (100 mg/kg) much lower than BPA used in BNCT.16–20 Despite the similarity in chemical structures of phenylalanine and boronophenylalanine (BPA), the selective tissue/tumor uptake and agent dosage as well as administration schemes are very different between phenylalanine in PKU studies and BPA and BNCT. First, the tumor uptake of BPA is about 3.5 times higher than normal tissue and blood while phenylalanine uptake in normal tissue is much lower than its blood concentration. Second, the BPA dosage is used at ~300 mg/kg via i.v. in BNCT, about three times higher than phenylalanine used orally in PKU. These differences suggest that in vivo observation of BPA in tumor do not have to use a voxel as large as 78 cm3 referred in the PKU studies.16 The results of the PKU studies suggest that in vivo existing phenylalanine and tyrosine are unlikely to give background interference to BPA observation in BNCT, and that because of the higher BPA dose and higher uptake in tumor, proton NMR of BPA should be practically useful for quantitative measurement in clinical BNCT.

The much higher gyromagnetic ratio of 1H than of B-10 or B-11 greatly increases the BPA spectral signal intensity, and hence, its NMR detectability in vivo. Moreover, as mentioned previously, B-10 and B-11 are not readily amenable to NMR measurement in the context of BNCT since in clinical BNCT 98% of boron is B-10-enriched boron (with a very low gyromagnetic ratio) while B-11, despite its higher gyromagnetic ratio, is only present in physiologically minute concentrations as the result of the B-10 enrichment.

BNCT has become a potentially useful treatment modality for malignant brain tumors. In addition to the development of more suitable boron delivery agents, a major challenge in BNCT has been to optimize the dose distribution by temporal targeting approaches, namely, neutron irradiation at the best time window during the pharmacokinetic wash-in and wash-out of the boron delivery agent. Currently, with the exception of positron emission tomography (PET) scanning employing specially formulated F-18 labeled BPA fructose, there is no practical and noninvasive method for measuring temporal boron concentration variations in blood, normal brain, and brain tumor unless specially “reverse-enriched” boron delivery agents are employed—in which case B-11 NMR is also a feasible approach. Proton NMR measurement of BPA may have advantages over the PET, B-10 proton double resonance, and B-11 NMR techniques in that it does not involve any ionizing radiation, does not require complicated double-resonance experimental operations, and does not require “reverse enrichment” of the boronated delivery agent. Additionally, the measurement of pharmacokinetic distributions is of importance for improved radiation dosimetry for BNCT.

V. SUMMARY

In this preliminary study the feasibility of using proton NMR to measure BPA concentrations in BNCT applications has been demonstrated. It has been shown that BPA produces a proton NMR signature between 7.1–7.4 and 2–4 ppm, and that the 7.1–7.4 ppm aromatic proton signals are useful for BPA in vivo measurements. With the success of the present investigation, the next stage of this project will be to optimize the NMR acquisition procedures in human subjects using a 1.5 T clinical MR scanner. Our preliminary results indicate that proton NMR is likely to be a useful technique for noninvasive BPA measurement in clinical BNCT.

Acknowledgments

C.Z. was supported in part by a grant from the Whitaker Foundation (G-96-004), P.V.P by a grant-in-aid from the American Heart Association and NIH (RO1 DK53221), and R.G.Z. by a grant from DOE (DE-FG02-96ER62193). The authors greatly appreciate the comments on this work from Dr. R. Edelman, Dr. J. Ingwall, and Dr. R. V. Mulkern. The authors thank Dr. N. Adnani for stimulating discussion and providing the brain metabolite phantoms. C.Z. acknowledges beneficial discussions and/or technical support from Dr. T. Sano, Dr. M. Palmer, Dr. D. Burstein, D. J. Suojanen, Dr. C. Yam and Dr. M. Zhang, and A. Bashir, S. Gladstone, and S. Kiger, during the course of this work.

References

- 1.Wazer DE, Zamenhof RG, Harling OK, Madoc-Jones H. Boron neutron capture therapy. In: Mauch PM, Loeffler JS, editors. Radiation Oncology: Technology and Biology. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barth RF, Soloway AH, Fairchild RG, Brugger RM. Boron neutron capture therapy for cancer. Cancer (NY) 1992;70:2995–3007. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921215)70:12<2995::aid-cncr2820701243>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley J, Harling OK. Boron-10 analyses using prompt gamma neutron activation analysis and ICP-AES. Trans Am Nucl Soc. 1996;75:31–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harling OK, Chabeuf JM, Lambert F, Yasuda G. A prompt gamma neutron activation analysis facility using a diffracted beam. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B. 1993;83:557–562. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendel P, Zilberstein J, Salomon Y. In vivo detection of a boron–neutron-capture agent in melanoma by proton observed 1H-10B double resonance. Magn Reson Med. 1994;32:170–174. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bendel P, Frantz A, Zilberstein J, Kabalka GW, Salomon Y. Boron-11 NMR of boro captate: relaxation and in vivo detection in melanoma-bearing mice. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39:439–447. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradshaw KM, Hadley JR, Buswell H, Hendee SP, McAllister L, Heilbrun MP, Fults DW, III, Schweizer MP. B11 MRI studies of BSH pharmacokinetics in high-grade human brain tumors. In: Larsson B, Crawford J, Weinreich R, editors. Advances in Neutron Capture Therapy Volume II, Chemistry and Biology, Proceedings of the Seventh International Symposium on Neutron Capture Therapy for Cancer. Vol. 2. Elsevier; Zurich, Switzerland: 1996. pp. 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang PP, Schweizer MP, Bradshaw KM, Bauer WF. 11B nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the interaction of borocapture sodium with serum albumin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;49:625–632. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)00529-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cady EB. Quantitative combined phosphorus and proton PRESS of the brains of newborn human infants. Magn Reson Med. 1995;33:557–563. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coderre JA, Chanana AD, Joel DD, Elowitz EH, Micca PL, Nawrocky MM, Chadha M, Gebbers JO, Shady M, Peress NS, Slatkin DN. Biodistribution of boronophenylalanine in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: Boron concentration correlates with tumor cellularity. Radiat Res. 1998;149:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elowitz EH, Bergland RM, Coderre JA, Joel DD, Chadha M, Chanana AD. Biodistribution of p-boronophenylalanine in patients with glioblastoma multiforme for use in boron neutron capture therapy. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:463–468. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199803000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mori Y, Suzuki A, Yoshino K, Kakihana H. Complex formation of p-boronophenylalanine with some monosaccharides. Pigment Cell Res. 1989;2:273–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1989.tb00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori S, Eleff SM, Pilatus U, Mori N, van Zijl P. Proton NMR spectroscopy of solvent-saturable resonances: A new approach to study pH effects in situ. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40:36–42. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu J, Chen W, Barger GR, Evelhoch J. In vivo proton MRS of human brain in the aromatic region. presented at the ISMRM; Vancouver. 1997; (unpublished) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreis R, Ernst T, Ross BD. Development for the human brain: In vivo quantification of metabolite and water content with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30:424–437. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreis R, Pietz J, Penzien J, Herschkowitz N, Boesch C. Identification and quantitation of phenylalanine in the brain of patients with phenylketonuria by means of localized in vivo 1H MRS. J Magn Reson, Ser B. 1995;107:242–251. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novotny EJ, Avison M, Herschkowitz N, Petroff O, Prichard J, Seashore M, Rothman D. In vivo measurement of phenylalanine in human brain by proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Pediatr Res. 1995;37:244–249. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199502000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pietz J, Kreis R, Schmidt H, Meyding-Lamade U, Rupp A, Boesch C. Phenylketonuria: Findings at MR imaging and localized in vivo H-1 MR spectroscopy of the brain in patients with early treatment. Radiology. 1996;201:413–420. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.2.8888233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moller H, Weglage J, Wiedermann D, Ullrich K. Blood–brain barrier phenylalanine transport and individual vulnerability in phenylketonuria. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1184–1191. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moller H, Vermathen P, Ullrich K, Weglage J, Koch H, Peters P. In vivo NMR spectroscopy in patients with phenylketonuria: Changes of cerebral phenylalanine levels under dietary treatment. Neuropediatrics. 1995;26:199–202. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]