Abstract

Type I interferons (IFNs) were long considered to be the sole IFN species produced by virus-infected cells until the discovery of type III IFNs (IFNλs), decades later. Like type I IFNs, type III IFNs are induced by and protect against viral infections, leading to the initial conclusion that the two IFN species are identical in regulation and biological functions. However, the two systems differ in the tissue expression of their receptor, resulting in different roles in vivo. The unique nature of IFNλs has been further demonstrated by recent studies revealing differences in the regulation of type I and III IFN expression, and how these proteins elicit specific cellular responses. This review focuses on the distinctive features of type III IFNs in antiviral innate immunity.

Introduction

Interferons are secreted proteins that are defined by their ability to confer resistance to viral infections. Historically type I IFNs were thought to be the only species produced by non-lymphoid cells in response to viral infections, and able to activate innate and adaptive immunity. However, many different examples of antiviral signaling occurring in a type I IFN-independent manner have been described [1–6]. The specific mechanisms that govern these processes are unclear but could be explained, at least in part, by the actions of type III IFNs [7,8]. The type III IFN family is composed of three genes: IFNλ1(IL29), IFNλ2 (Il28A) and IFNλ3 (IL28B). A fourth member, IFNλ4, was identified more recently and is a poorly understood frameshift variant of IIL28B that predicts Hepatitis C virus clearance and response to IFN therapies [9]. In humans, IFNλ1 is the most prominent and best studied species, but it is a pseudogene in mice [10]. Type III IFNs signal through the IFNλ receptor (IFNλR) which is composed of two chains: IL28Rα, a unique subunit, and IL10Rβ, shared with cytokines of the IL10 family. Like the type I IFN receptor (IFNAR), binding of the IFNλR results in the activation of JAK/STAT signaling, expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) and induction of an antiviral state. However, unlike IFNAR, which is expressed on virtually all cell types, IL28Rα is only expressed on specific tissues such as epithelia. Initial reports have focused on the similar activities of type I and III IFNs, but recent work has revealed unique properties of IFNλs and have established them as the primary regulators of antiviral immunity at mucosal surfaces, especially in the intestine [11]. This review focuses on the fundamental differences between type I and III IFN biology.

IFNλR signaling

Similar to type I and II IFNs, ligation of the IFNλR leads to the activation of kinases of the JAK family and phosphorylation of several members of the STAT family of transcription factors [7,12,13]. Once phosphorylated, STAT1 and 2 associate with a third protein called IRF9 to form a transcription complex termed IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3). ISGF3 translocates to the nucleus to induce the expression of ISGs [14]. The IL10Rβ chain is shared with cytokines of the IL10 family and signals via Tyk2, leading to the speculation that Tyk2 mediates IFNλ signaling. Original studies on the IL28Rα carried out prior to the identification of IFNλs concluded that JAK1, but not JAK2, mediate IFNλ signaling [12]. However, it was recently shown in a more physiological context that JAK2 is indeed phosphorylated by type III IFNs [15,16]. In addition, inhibitor and RNAi studies have shown that JAK2 is necessary for STAT1 phosphorylation in response to IFNλs, and that JAK2 mediates antiviral signaling in cells that only produce type III IFNs [15]. In these studies, JAK1 was confirmed as a mediator of IFNλ signaling, but further work is needed to determine whether Tyk2 is involved in this pathway. Therefore, type I and III IFNs appear to signal via different JAK/STAT pathways, but no unique ISG among the 300 produced by IFNλ has been identified [13,17,18].

Type III IFN targets and biological activities

Recent studies have revealed important differences in the biological functions of type I and III IFNs. These differences primarily stem from the fact that all cells respond to type I IFNs, while only a small subset responds to type III. This functional tissue–specificity is due to the expression of the IL28Rα subunit, which is only expressed on epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal, intestinal and reproductive tracts and some immune cells [11,19,20]. Consequently, type III IFNs are not able to able to confer protection against systemic virus infections. Rather, these IFN are most effective at controlling viral infections at mucosal surfaces [21–23]. Evidence supporting this idea comes from recent work comparing the relative importance of the IFNAR and IFNλR in the control of rotavirus, an RNA virus that primarily infects intestinal epithelial cells. Whereas IFNAR-deficient mice controlled viral replication in the intestine, IL28Rα-deficient intestinal epithelial cells could not mount an effective IFN response and were unable to control rotavirus infection. Furthermore, systemic treatment of infected animals with IFNλ, but not IFNβ, repressed rotavirus infection in the intestine [22]. In vitro studies of human intestinal epithelial cells support the idea that type III IFN induction and responsiveness are key aspects of the biology of these cells. For example, the differentiation state of intestinal epithelial cells dictates the quality of the IFN response, with increasing IFNλ produced as cells polarize [15], suggesting that epithelial cell biology is intimately linked with the type III IFN system.

Regulation of type III IFN expression

Type I and III IFNs are produced following recognition of viral ligands, most prominently nucleic acids, by a wide range of pattern recognition receptors. On endosomes, viral nucleic acids are recognized by Toll-like receptor (TLR) 3, 7/8 and 9. cGAS, STING and RIG-I like receptors (RLRs) perform the same functions in the cytosol. TLR ligands induce type III IFNs concomitantly with type I, but the pathways activated are unknown [24–27]. Similarly type III IFNs are induced by, and protect against DNA viruses [28–30], but the precise mechanisms driving these processes have yet to be studied. Type III IFN expression in response to RNA viruses is best understood, and involves RLRs, MAVS and TBK1, like type I IFNs [15,31–33]. However, the subcellular localization of MAVS determines which IFN species is produced. MAVS is an adapter of the RLR pathway that was first identified as being localized on mitochondria [34] and was later shown to also localize to peroxisomes [1] and mitochondrial-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes [35]. From peroxisomes, MAVS is able to induce ISGs and control viral infections independently of type I IFNs [1]. Indeed, transgenic cell lines preferentially expressing MAVS on peroxisomes only induced type III IFNs in response to a variety of intracellular ligands [15]. In addition, the function and abundance of peroxisomes and mitochondria determines the quality of the IFN response. Increasing peroxisomal abundance or inhibiting mitochondrial function favors the expression of type III over type I IFNs. This observation could reflect what happens physiologically in epithelia. Indeed, polarization of epithelial cells increases peroxisome abundance and type III IFN responses to viral infections, while the number of mitochondria and type I IFN expression are unaffected [15].

Type I and III IFNs are also differentially regulated at the transcriptional level. IFNβ, the prototypical type I IFN, is induced by the combined actions of the transcription factors AP-1, interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 3 and IRF7 and NFκB. The binding sites for each set of transcription factors are localized in close proximity to each other and IFNβ expression requires the co-operative binding of all activators in a complex termed the enhanceosome [36,37]. The IFNλ1 promoter contains binding sites for the same sets of transcription factors. However, only IRF3, 7 and NFκB are required for type III IFN induction [15,33,38]. In fact, MAP kinases that activate AP-1 are not required for type III IFN production in response to RNA viruses, demonstrating that AP-1 is dispensable in the IFNλ1 pathway [15].

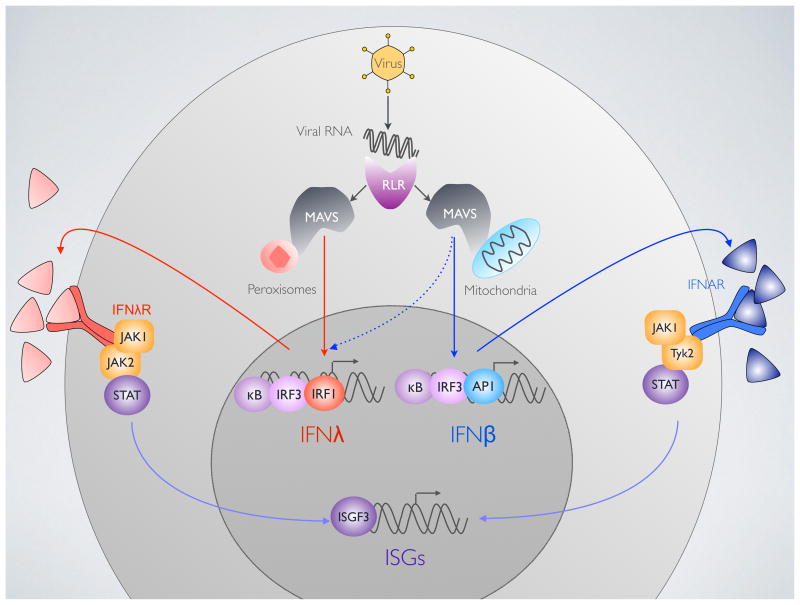

Both IFN families also contain binding sites for IRF1, the first IRF identified. Although first reports concluded that IRF1 bound the IFNβ promoter, IRF1 KO mice and cells are unimpaired in their ability to induce type I IFN expression [39]. However, IRF1 is known to be important in antiviral defense, and was thought to act in an interferon-independent manner [1,2]. Recent studies have confirmed that IRF1 does not induce IFNβ [15], but does instead control type III IFN expression in response to RNA viruses [15,40,41]. In addition, while IFNβ regulation requires all components of the enhanceosome, it appears that type III IFNs can be induced through the independent action of IRFs and NFκB [42]. This finding has important implications: first, the limited number of transcription factors it requires explains the very high inducibility of type III IFNs. Also, if NFκB and IRFs can independently induce type III IFNs, one can predict that this pathway is less susceptible to be successfully targeted by pathogens. These findings define unique pathways for the induction of each IFN family: IRF3/7 and NFκB are activated by both mitochondrial and peroxisomal MAVS to mediate the expression of both IFN classes. However, MAVS on peroxisomes activates IRF1 to only regulate type III IFNs while MAVS on mitochondria can activate MAP kinases to induce type I IFNs (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Signaling upstream and downstream of type III interferons (IFNs).

MAVS on peroxisomes mediates type III IFN (IFNλ) signaling downstream of viral RNA detection by RIG-I like receptors (RLRs). IFNλ is expressed by IRF1, IRF3 and NFκB. Type I IFN (IFNβ) is induced by the combined action of IRF3, NFκB and AP-1, downstream of peroxisomal MAVS.

Ligation of the type I IFN receptor (IFNAR) activates JAK1 and Tyk2 to induce ISG expression through ISGF3. The type III IFN receptor (IFNλR) probably requires JAK1 and JAK2 to activate STAT phosphorylation.

Simple tools to study type III IFNs in mouse systems

Most studies on type III IFNs have been carried out in human systems as the tools to study mouse IFNλs are lacking. As type I and III IFNs differ in their ability to activate JAK2 [15,16], immunoblotting against phosphorylated JAK2 can report type III IFN signaling in a given experimental system. In parallel, JAK2 RNAi, knockout and/or inhibition with pharmacological inhibitors such as AG490 or 1,2,3,4,5,6-Hexabromocyclohexane [43] will specifically block type III IFN signaling without affecting type I [15].

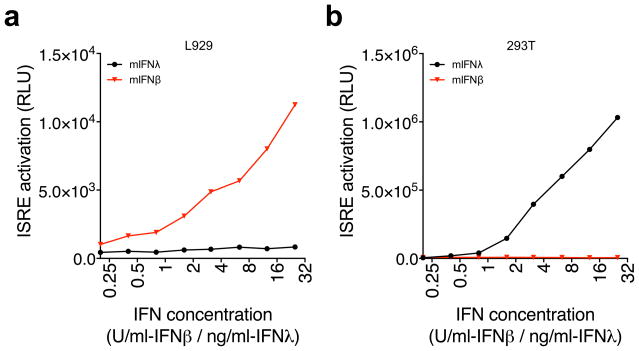

As a complementary method, we have developed a very simple bioassay that enables the quick and distinct detection of mouse type I and III IFNs. Our system utilizes human 293T and mouse L929 cells that express luciferase under the control of an ISRE promoter, the sequence activated by type I and III IFNs. L929 readily respond to mouse IFNβ in a dose-dependent manner but they do not respond to IFNλ2 (Fig. 2a). Therefore, these cells can be used to detect IFNβ without detecting IFNλ. To selectively detect IFNλ we took advantage of the fact that IFNβ cannot signal across species while IFNλs do (Fig. 2b). Therefore human 293T-ISRE cells can be used to specifically detect mouse type III IFNs, without detecting type I. These bioassays are simple and inexpensive, and are very efficient at detecting specific IFN species.

Figure 2.

Bioassays to specifically detect IFNβ and IFNλ in mouse cells. L929 cells do not respond to mouse IFNλ2 but enable the detection of increasing concentrations of mouse IFNβ (a). As IFNλs are able to signal across species but IFNβ is not, human 293T cells are able to detect mouse IFNλ2 but not IFNβ. Units are in μg/ml (IFNλ2) or in units/ml (IFNβ).

Conclusions

Recent studies have revealed that the transcriptional regulation of type I and III IFNs are fundamentally different, and that the cellular signaling pathways that drives expression of each subtype can also differ. But perhaps the most fundamental difference between the two systems is their physiological functions in vivo, with type III IFNs being the main drivers of antiviral immunity at mucosal surfaces. This tissue-restricted function of type III IFNs has implications in IFN-mediated therapies. PEGylated IFNα has long been used to treat chronic viral infections such as Hepatitis B/C, which infects hepatocytes. However, this treatment is associated with side effects that limit its use. As human hepatocytes express IFNλR but most cells in the body do not, IFNλ clinical trials have been very promising in both effectiveness and limitation of side effects [44]. The innate immune system is often described as the first line of defense against pathogens. Among this first line of defense, the first soldiers exposed to pathogens are epithelial cells that constitute the barrier between us and the outside world. The fundamental role of type III IFNs in this tissue therefore makes them an essential weapon in our arsenal against pathogens.

Highlights.

Type III interferons are antiviral factors that are expressed in response to numerous viral infections.

Type III interferons are most critical for controlling viral infections at mucosal surfaces.

Unlike Type I interferons, Type III interferons induce JAK2-dependent innate immune responses.

RIG-I like Receptor signal transduction from peroxisomes specifically induces the expression of Type III interferons via IRF1.

Acknowledgments

J.C.K. is supported by NIH grants AI093589, AI072955, AI113141-01, and an unrestricted gift from Mead Johnson & Company. Dr. Kagan holds an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. C.O. is supported by a Fellowship from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dixit E, Boulant S, Zhang Y, Lee ASY, Odendall C, Shum B, Hacohen N, Chen ZJ, Whelan SP, Fransen M, et al. Peroxisomes are signaling platforms for antiviral innate immunity. Cell. 2010;141:668–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stirnweiss A, Ksienzyk A, Klages K, Rand U, Grashoff M, Hauser H, Kroger A. IFN Regulatory Factor-1 Bypasses IFN-Mediated Antiviral Effects through Viperin Gene Induction. The Journal of Immunology. 2010;184:5179–5185. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pulit-Penaloza JA, Scherbik SV, Brinton MA. Type 1 IFN-independent activation of a subset of interferon stimulated genes in West Nile virus Eg101-infected mouse cells. Virology. 2012;425:82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noyce RS, Collins SE, Mossman KL. Identification of a novel pathway essential for the immediate-early, interferon-independent antiviral response to enveloped virions. The Journal of Virology. 2006;80:226–235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.226-235.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noyce RS, Taylor K, Ciechonska M, Collins SE, Duncan R, Mossman KL. Membrane perturbation elicits an IRF3-dependent, interferon-independent antiviral response. Journal of Virology. 2011;85:10926–10931. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00862-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peltier DC, Lazear HM, Farmer JR, Diamond MS, Miller DJ. Neurotropic arboviruses induce interferon regulatory factor 3-mediated neuronal responses that are cytoprotective, interferon independent, and inhibited by Western equine encephalitis virus capsid. Journal of Virology. 2013;87:1821–1833. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02858-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7**.Kotenko SV, Gallagher G, Baurin VV, Lewis-Antes A, Shen M, Shah NK, Langer JA, Sheikh F, Dickensheets H, Donnelly RP. IFN-lambdas mediate antiviral protection through a distinct class II cytokine receptor complex. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:69–77. doi: 10.1038/ni875. In this paper, the type III IFN receptor is defined as being composed of IFN28Rα and IL10Rβ, and its ligands are shown to be IFNλs1-3, also known as IL29, IL28A and IL28B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8**.Sheppard P, Kindsvogel W, Xu W, Henderson K, Schlutsmeyer S, Whitmore TE, Kuestner R, Garrigues U, Birks C, Roraback J, et al. IL-28, IL-29 and their class II cytokine receptor IL-28R. Nat Immunol. 2002;4:63–68. doi: 10.1038/ni873. In this paper IL29, Il28A and IL28B are shown to be induced in response to viral infections, and to exhibit similar activities as type I IFNs. The IFNλ receptor is shown to be a dimer of IL10Rβ and IL28Rα. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prokunina-Olsson L, Muchmore B, Tang W, Pfeiffer RM, Park H, Dickensheets H, Hergott D, Porter-Gill P, Mumy A, Kohaar I, et al. A variant upstream of IFNL3 (IL28B) creating a new interferon gene IFNL4 is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nat Genet. 2013;45:164–171. doi: 10.1038/ng.2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasfar A, Lewis-Antes A, Smirnov SV, Anantha S, Abushahba W, Tian B, Reuhl K, Dicken-sheets H, Sheikh F, Donnelly RP, et al. Characterization of the mouse IFN-lambda ligand-receptor system: IFN-lambdas exhibit antitumor activity against B16 melanoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4468–4477. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11**.Sommereyns C, Paul S, Staeheli P, Michiels T. IFN-Lambda (IFN-λ) Is Expressed in a Tissue-Dependent Fashion and Primarily Acts on Epithelial Cells In Vivo. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4:e1000017. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000017. The IFNλR is primarily expressed in epithelia, and the IFNλ system is shown to be primarily important for antiviral defenses at mucosal surfaces. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumoutier L, Lejeune D, Hor S, Fickenscher H, Renauld J-C. Cloning of a new type II cytokine receptor activating signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)1, STAT2 and STAT3. Biochem J. 2003;370:391–396. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13*.Dumoutier L, Tounsi A, Michiels T, Sommereyns C, Kotenko SV, Renauld J-C. Role of the interleukin (IL)-28 receptor tyrosine residues for antiviral and antiproliferative activity of IL-29/interferon-lambda 1: similarities with type I interferon signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32269–32274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404789200. This paper, published shortly after references 7 and 8 studies the IFNλR without identifying IFNλs as being its ligand. Chimeras of the IL28Rα (called LICR2 in this study) cytoplasmic domain and the IL10R ecto domain were used to study signaling by the IL28Rα. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BRG, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. HOW CELLS RESPOND TO INTERFERONS. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15**.Odendall C, Dixit E, Stavru F, Bierne H, Franz KM, Durbin AF, Boulant S, Gehrke L, Cossart P, Kagan JC. Diverse intracellular pathogens activate type III interferon expression from peroxisomes. Nat Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ni.2915. This study describes the differential regulation of type I and III IFNs by the RIG-I/MAVS pathway. JAK2 is shown to be activated by type III but not type I IFNs. MAP kinases are shown to be dispensable for type III IFN signaling, while IRF1 regulates type III but not type I IFN expression. MAVS localized on peroxisomes is shown to only induce type III IFNs. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16*.Lee S-J, Kim W-J, Moon S-K. Role of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway in mediating inter-leukin-28A-induced migration of UMUC-3 cells. Int J Mol Med. 2012 doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2012.1064. IL28A is shown to induce JAK2 phosphorylation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diegelmann J, Beigel F, Zitzmann K, Kaul A, Goke B, Auernhammer CJ, Bartenschlager R, Diepolder HM, Brand S. Comparative analysis of the lambda-interferons IL-28A and IL-29 regarding their transcriptome and their antiviral properties against hepatitis C virus. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doyle SE, Schreckhise H, Khuu-Duong K, Henderson K, Rosler R, Storey H, Yao L, Liu H, Barahmand-pour F, Sivakumar P, et al. Interleukin-29 uses a type 1 interferon-like program to promote antiviral responses in human hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2006;44:896–906. doi: 10.1002/hep.21312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Z, Hamming OJ, Ank N, Paludan SR, Nielsen AL, Hartmann R. Type III Interferon (IFN) Induces a Type I IFN-Like Response in a Restricted Subset of Cells through Signaling Pathways Involving both the Jak-STAT Pathway and the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases. The Journal of Virology. 2007;81:7749–7758. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02438-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mordstein M, Neugebauer E, Ditt V, Jessen B, Rieger T, Falcone V, Sorgeloos F, Ehl S, Mayer D, Kochs G, et al. Lambda Interferon Renders Epithelial Cells of the Respiratory and Gastrointestinal Tracts Resistant to Viral Infections. Journal of Virology. 2010;84:5670–5677. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00272-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okabayashi T, Kojima T, Masaki T, Yokota S. Type-III interferon, not type-I, is the predominant interferon induced by respiratory viruses in nasal epithelial cells. Virus research. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.07.011. [no volume] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22**.Pott J, Mahlakõiv T, Mordstein M, Duerr CU, Michiels T, Stockinger S, Staeheli P, Hornef MW. IFN-lambda determines the intestinal epithelial antiviral host defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2011;108:7944–7949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100552108. Mice deficient for type I (IFNAR) or the IFNλR are compared for their ability to resist rotavirus infection. IFNλR but not IFNAR mice are shown to be deficient in ISG expression, control of virus replication in epithelia and limitation of intestinal epithelial cell damage. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jewell NA, Cline T, Mertz SE, Smirnov SV, Flano E, Schindler C, Grieves JL, Durbin RK, Kotenko SV, Durbin JE. Interferon-{lambda} is the predominant interferon induced by influenza A virus infection in vivo. Journal of Virology. 2010 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01703-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makela SM, Osterlund P, Julkunen I. TLR ligands induce synergistic interferon-β and interferon-λ1 gene expression in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Molecular immunology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.10.005. [no volume] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siren J, Pirhonen J, Julkunen I, Matikainen S. IFN-alpha regulates TLR-dependent gene expression of IFN-alpha, IFN-beta, IL-28, and IL-29. J Immunol. 2005;174:1932–1937. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coccia EM, Severa M, Giacomini E, Monneron D, Remoli ME, Julkunen I, Cella M, Lande R, Uzé G. Viral infection and Toll-like receptor agonists induce a differential expression of type I and lambda interferons in human plasmacytoid and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:796–805. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27*.Ank N, Iversen M, Bartholdy C. An important role for type III interferon (IFN-λ/IL-28) in TLR-induced antiviral activity. The Journal of …. 2008 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2474. [no volume]. This paper shows that type III IFNs are produced by most cells in response to TLR ligands and viruses, but that only plasmacytoid dendritic cells and epithelial cells are able to respond to IFNλ. This study also describes IL28Rα KO mice. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sui H, Zhou M, Chen Q, Lane HC, Imamichi T. siRNA enhances DNA-mediated interferon lambda-1 response through crosstalk between RIG-I and IFI16 signalling pathway. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42:583–598. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Hu S, Zhou L, Ye L, Wang X, Ho J, Ho WZ. Interferon lambda inhibits herpes simplex virus type I infection of human astrocytes and neurons. Glia. 2011 doi: 10.1002/glia.21076. [no volume] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melchjorsen J, Siren J, Julkunen I, Paludan SR, Matikainen S. Induction of cytokine expression by herpes simplex virus in human monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells is dependent on virus replication and is counteracted by ICP27 targeting NF-kappaB and IRF-3. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1099–1108. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okamoto M, Oshiumi H, Azuma M, Kato N, Matsumoto M, Seya T. IPS-1 is essential for type III IFN production by hepatocytes and dendritic cells in response to hepatitis C virus infection. The Journal of Immunology. 2014;192:2770–2777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onoguchi K, Yoneyama M, Takemura A, Akira S, Taniguchi T, Namiki H, Fujita T. Viral infections activate types I and III interferon genes through a common mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7576–7581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osterlund P, Veckman V, Siren J, Klucher KM, Hiscott J, Matikainen S, Julkunen I. Gene Expression and Antiviral Activity of Alpha/Beta Interferons and Interleukin-29 in Virus-Infected Human Myeloid Dendritic Cells. The Journal of Virology. 2005;79:9608–9617. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9608-9617.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seth RB, Sun L, Ea C-K, Chen ZJ. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell. 2005;122:669–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horner SM, Liu HM, Park HS, Briley J, Gale M. Mitochondrial-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) form innate immune synapses and are targeted by hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2011;108:14590–14595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110133108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thanos D, Maniatis T. Virus induction of human IFNβ gene expression requires the assembly of an enhanceosome. Cell. 1995;83:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panne D. The enhanceosome. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Onoguchi K, Yoneyama M, Fujita T. Retinoic acid-inducible gene-I-like receptors. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:27–31. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reis LFHRGSMACW. Mice devoid of interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) show normal expression of type I interferon genes. EMBO J. 1994;13:4798. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ueki IF, Min-Oo G, Kalinowski A, Ballon-Landa E, Lanier LL, Nadel JA, Koff JL. Respiratory virus-induced EGFR activation suppresses IRF1-dependent interferon λ and antiviral defense in airway epithelium. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2013;210:1929–1936. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siegel R, Eskdale J, Gallagher G. Regulation of IFN-λ1 promoter activity (IFN-λ1/IL-29) in human airway epithelial cells. 2011. [no volume] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomson SJP, Goh FG, Banks H, Krausgruber T, Kotenko SV, Foxwell BMJ, Udalova IA. The role of transposable elements in the regulation of IFN-lambda1 gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2009;106:11564–11569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904477106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandberg EM, Ma X, He K, Frank SJ, Ostrov DA, Sayeski PP. Identification of 1,2,3,4,5,6-Hexabromocyclohexane as a Small Molecule Inhibitor of Jak2 Tyrosine Kinase Auto-phophorylation. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2526–2533. doi: 10.1021/jm049470k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller D, Klucher K, Freeman J. Interferon lambda as a potential new therapeutic for hepatitis C. Annals of the New …. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05241.x. [no volume] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]