Abstract

Dengue virus is the causative agent of dengue virus fever. It infects about 400 million people per year and leads to about 21,000 deaths annually. There is available neither a fully successful vaccine nor a successful drug therapy. Some dengue virus serotypes undergo a temperature dependent conformational change from a “smooth” form at lower temperatures to a “bumpy” form at temperatures approaching 37°C, the human body temperature. The bumpy structure is less stable and is likely an intermediate in the formation of a fusogenic virus particle.

Introduction

Dengue virus (DENV), a mosquito-borne, positive-stranded RNA flavivirus, causes disease in about 400 million people worldwide every year, resulting in about 21,000 deaths [1] annually. There are five dengue virus serotypes, DENV1 to DENV5 [2]. Infection by any one serotype results in lifelong protection against the same serotype. However, a subsequent infection by another dengue virus serotype increases the risk of developing dengue hemorrhagic fever, a more severe disease [3]. Currently, there is available neither a licensed vaccine nor an anti-viral drug.

The 11-kb viral genome encodes an envelope (E) glycoprotein, a pre-membrane (prM) protein, a capsid protein and seven non-structural proteins. The E protein has four domains (DI, DII, DIII and the stem domain) that connect to a transmembrane region [4–6]. DI is the N-terminal domain positioned between DII and DIII. The conserved hydrophobic fusion loop is at the end of DII, distal to DIII. DIII has an lg-like domain, suggesting that it might be required for attachment to a cellular receptor. The E protein forms 90 dimers on the smooth surface of the mature virus [12**] with the fusion loop peptides buried under DI of neighboring E molecules. The prM protein consists of the N-terminal pr domain and the C-terminal M protein. The pr domain exists only in the immature structure and is cleaved off prior to maturation.

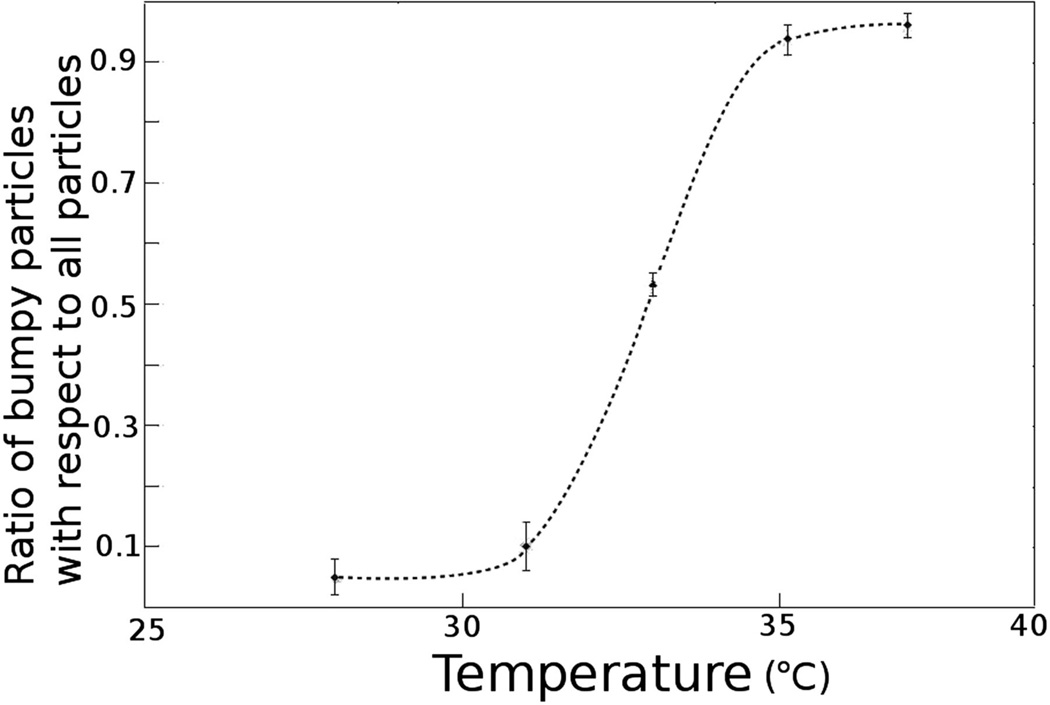

DENV undergoes several major conformational changes during its life cycle. In the endoplasmic reticulum of an infected cell, newly assembled immature DENV is icosahedral with a rough surface formed by 60 spikes, each of which is a quasi-trimer of E and prM proteins [7, 8]. The first conformational change occurs during maturation [8] in the acidic environment of the trans-Golgi network. The 60 (E:prM)3 trimeric spikes of the immature particle change to 90 (E2) dimers and expose the prM protein cleavage site. The Pr protein is cleaved from prM by furin to form a smooth, mature virion. The infectious virus can then enter a host cell by receptor mediated endocytosis. The second conformational change occurs during fusion with the endosomal membrane in the low pH environment of endosomes [9, 10] prior to cell entry. The acidic pH causes the 90 E protein dimers of the mature virus to disassociate and to re-associate as 60 “open” pre-fusion trimers on the viral surface [10]. The exposed fusion loop peptides on the tip of the pre-fusion trimers can insert themselves into the endosomal membrane to start the fusion process. The viral genome is then released into the cell cytoplasm. In addition to these changes, a temperature-dependent conformational transition of the DENV-2 virion can occur in which the “smooth” surface of the virus below about 33°C becomes “bumpy” at higher temperatures, such as within humans (Fig. 1) [11**, 12**].

Figure 1.

Transition of the smooth mature virus to a proposed fusion intermediate. (A) Cryo-EM image of DENV particles at 37°C. Most of the DENV particles have a bumpy conformation. Black arrows point to an occasional smooth particle. White arrows point to deformed particles with different sizes. Figure 1A reproduced from X. Zhang et al. [11**] Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110:6795–6799. (B) The structure of DENV at room temperature. (C) A structural intermediate similar to the bumpy structure at 37°C [11**]. (D) The proposed structure of DENV, according to Ferlenghi et al. [15]. Figure 1B-D reproduced from Kuhn et al. [13] Cell 2002, 108:717–725.

The rearrangement of E glycoprotein on the viral surface at high temperature

The three-dimensional structures of DENV were studied by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), combined with the earlier X-ray crystallographic structure of a homologous E glycoprotein dimer [4] to produce a pseudo-atomic resolution of the viral capsid [13]. This showed that the 90 E protein dimers (30 located on the icosahedral 2-fold axes and 60 in general positions) cover the whole viral membrane and form a “herringbone” configuration on the viral surface. These viral particles have a smooth surface and a diameter of about 500Å. The cryo-EM structure of these smooth surfaced mature DENV particles has now been extended to 3.5Å resolution [14].

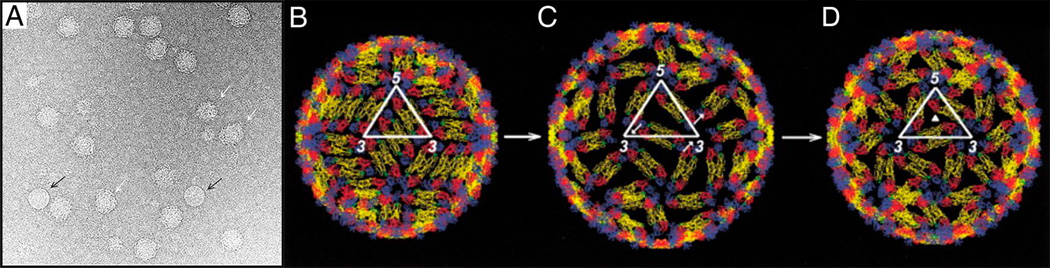

DENV particles undergo an irreversible conformational change from smooth to bumpy in a narrow 33 to 35°C temperature range (Fig. 2) [11**]. The bumpy structures of DENV2 16681 strain at 35°C [11**] and DENV2 New Guinea strain at 37°C [12**] have been reported. Both these studies showed that the bumpy viruses have a 10% larger diameter than the smooth virus and that the viral membrane is exposed especially near the icosahedral three-fold axes. The structure of the bumpy virus is similar to the predicted fusion intermediate between the smooth, room temperature, mature DENV structure and a fusogenic form of the virus (Fig 1) [11**, 15]. In these particles the E dimers in the general position of the herringbone pattern of the smooth particles are displaced radially outward relative to the dimers associated with the icosahedral two-fold axes. In addition, both types of dimers are slightly rotated relative to their position in the smooth low temperature structure. In New Guinea strain, the two E protein molecules in the dimer at the two-fold axes move in opposite directions perpendicular to the surface of the virus [12**]. As a result some epitopes that are hidden in the mature virus become exposed as demonstrated both by the structure itself and by the ability of DENV2 particles to bind certain antibodies only at elevated temperatures [10, 16]. The presence of some exposed membranes in the high temperature particles is to be expected because of their increased diameter compared with the low temperature smooth particles. Furthermore, the contacts between the E dimers are more limited, presumably reducing the stability of the bumpy virus structure. This contributes to the greater variation of structure between different bumpy particles as compared with the smooth particles, which in turn accounts for the much poorer final resolution achieved in the cryo-EM studies of bumpy particles [11**, 12**].

Figure 2.

Temperature titration. The ratio of bumpy particles to the total number of bumpy, smooth or deformed particles after incubating virus propagated at 28°C for 1 hr at different temperatures. The error was estimated by three different people counting the different kinds of particles. About 100 particles were counted at each temperature [11**]. Figure reproduced from X. Zhang et al. [11**] Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110:6795–6799.

Virus “breathing” versus temperature induced conformational change

Cryo-EM studies showed that anti-DENV monoclonal Fab fragments, such as E104 [10], and 1A1D-2 [16] can bind to and neutralize DENV2 only after the virus has been incubated at temperatures greater than 35°C for half an hour. However, these fragments cannot bind to smooth virus at room temperatures. It has been suggested that the virus is “breathing” [16] or oscillating between two conformations. Such “breathing” has been documented for the icosahedral picornaviruses that expose cleavage sites to proteases that are hidden in crystallographic structures of the virus [17]. Indeed, it would seem probable that most icosahedral viruses are subject to greater or lesser amounts of oscillatory “breathing”. The higher the temperature the greater would be the amplitude of the conformational changes sampled by the virus. Hence it was suggested that when dengue virus is heated to 35°C, the high temperature conformation would be captured by permanently jamming it “open” when an antibody binds to epitopes that were hidden in the low temperature conformation. However, heating the smooth low temperature virus in the absence of an antibody to 35°C produces an irreversible conformational change to the bumpy conformation. Once the smooth dengue virus has changed its conformation to being bumpy, it does not return to the smooth form when the temperature is subsequently lowered [11**]. Thus the virus structure cannot be oscillating between the smooth low temperature conformation and the bumpy high temperature conformation. Therefore, the high temperature bumpy conformation is not being sampled when the virus is “breathing” at a lower temperature. Similarly, the smooth low temperature conformation is not being sampled when the high temperature bumpy virus is “breathing”.

High temperature conformational change is strain dependent

The DENV16007 strain has a similar bumpy appearance at 37°C (unpublished results) as the abovementioned DENV2 strains. However, the DENV41086 strain did not have the conformational change at 37°C (unpublished results). In addition, the DENV1 PVP159 strain and the DENV4 SG/06K2270DK1/2005 strain did not exhibit conformational changes when incubated at 37°C [18]. The 4.1Å resolution cryo-EM electron density map of the DENV4 SG/06K2270DK1/2005 strain at room temperature [18] shows that there are more interdimeric contacts compared with the DENV2 New Guinea strain. In addition, DENV4 was shown to have higher thermal stability than other serotypes [19]. Thus, the DENV4 smooth structure might be more stable at 37°C than the DENV2 New Guinea strain, accounting for its lack of transition to a bumpy structure at higher temperatures.

The buried conserved fusion loop peptides of DENV1, DENV2 and DENV3 can be accessed by fusion loop-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) at 37°C. However, the fusion loop peptide of DENV4 did not become exposed to these MAbs until the incubation temperature was increased to 40°C [19]. Since DENV4 has higher thermal stability, the smooth-bumpy conformation transition might occur at a temperature higher than 37°C.

The strain dependent smooth-bumpy transition of DENVs indicates that different DENVs strains have different conformations when infecting humans. It will be necessary to consider this observation for the design of DENV vaccines.

The heterogeneity of bumpy DENV

As mentioned above, the interaction between E dimers is less in the bumpy particles than in the smooth particles [11**, 12**]. This might cause the bumpy particles to be less homogenous and to lack strict icosahedral symmetry. Thus the reconstruction of DENV2 16681 when incubated at 35°C achieved a resolution of only 35Å, although 515 particles had been carefully selected for their homogeneity from an initial 2500 boxed particle images [11**]. Similarly the reconstruction of DENV New Guinea strain when incubated at 37°C had been based on an initial set of 5681 bumpy particles. Nevertheless, in spite of the careful selection procedure, the correlation coefficient between the fitted coordinates and the density map dropped to less than 0.5 at resolutions better than 34Å.

Highlights.

Conformational change of dengue virus when heated to human body temperature.

The dengue virus high temperature conformational change is strain dependent.

The high temperature dengue virus structure is more variable than the low temperature structure.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Sheryl Kelly who helped in the preparation of the manuscript. Writing of this article was supported by NIH grant R01 AI076331 to MGR and Richard Kuhn as well as R01 AI077955 (to Michael S. Diamond, MGR, and Richard Kuhn).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Sankoh O, Myers MF, George DB, Jaenisch T, Wint GR, Simmons CP, Scott TW, Farrar JJ, Hay SI. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Normile D. Tropical medicine. Surprising new dengue virus throws a spanner in disease control efforts. Science. 2013;342:415. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6157.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halstead SB, O'Rourke EJ. Dengue viruses and mononuclear phagocytes. I. Infection enhancement by non-neutralizing antibody. J. Exp. Med. 1977;146:201–217. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.1.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rey FA, Heinz FX, Mandl C, Kunz C, Harrison SC. The envelope glycoprotein from tick-borne encephalitis virus at 2 Å resolution. Nature. 1995;375:291–298. doi: 10.1038/375291a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, Harrison SC. A ligand-binding pocket in the dengue virus envelope glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:6986–6991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832193100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Zhang W, Ogata S, Clements D, Strauss JH, Baker TS, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. Conformational changes of the flavivirus E glycoprotein. Structure. 2004;12:1607–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Lok SM, Yu IM, Zhang Y, Kuhn RJ, Chen J, Rossmann MG. The flavivirus precursor membrane-envelope protein complex, structure and maturation. Science. 2008;319:1830–1834. doi: 10.1126/science.1153263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu I-M, Zhang W, Holdaway HA, Li L, Kostyuchenko VA, Chipman PR, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG, Chen J. Structure of the immature dengue virus at low pH primes proteolytic maturation. Science. 2008;319:1834–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.1153264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stiasny K, Allison SL, Marchler-Bauer A, Kunz C, Heinz FX. Structural requirements for low-pH-induced rearrangements in the envelope glycoprotein of tick-borne encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 1996;70:8142–8147. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8142-8147.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Sheng J, Austin SK, Hoornweg TE, Smit JM, Kuhn RJ, Diamond MS, Rossmann MG. Structure of acidic pH dengue virus showing the fusogenic glycoprotein trimers. J. Virol. 2015;89:743–750. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02411-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang X, Sheng J, Plevka P, Kuhn RJ, Diamond MS, Rossmann MG. Dengue structure differs at the temperatures of its human and mosquito hosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:6795–6799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304300110. **An irreversible conformational change of dengue virus 2 strain 16681 was shown to occur at about 35°C when the viruses changes from having a “smooth” surface to a “bumpy” surface as the temperature increases. The 90 pairs of glycoprotein dimers on the low temperature smooth virus change to 60 trimeric bumps on the bumpy virus. The bumpy virus is expanded relative to the smooth conformation and has some exposed membrane. The bumpy structure is probably an intermediate in the formation of a fusogenic virus particle. The results suggested that the bumpy structure is required to infect humans. Therefore, this bumpy structure should be considered for vaccine design.

- 12. Fibriansah G, Ng TS, Kostyuchenko VA, Lee J, Lee S, Wang J, Lok SM. Structural changes in dengue virus when exposed to a temperature of 37°C. J. Virol. 2013;87:7585–7592. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00757-13. **A conformational change of dengue virus 2 New Guinea was found to occur when heated to 37°C. Four classes of dengue virus particles were observed at this temperature. The particles in the largest class had a rough surface and the glycoprotein shell was expanded exposing some viral membrane. This explains why some epitopes were hidden at a lower temperature but were accessible at higher physiological temperatures.

- 13.Kuhn RJ, Zhang W, Rossmann MG, Pletnev SV, Corver J, Lenches E, Jones CT, Mukhopadhyay S, Chipman PR, Strauss EG, Baker TS, Strauss JH. Structure of dengue virus, implications for flavivirus organization, maturation, and fusion. Cell. 2002;108:717–725. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00660-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Ge P, Yu X, Brannan JM, Bi G, Zhang Q, Schein S, Zhou ZH. Cryo-EM structure of the mature dengue virus at 3.5-Å resolution. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:105–110. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferlenghi I, Clarke M, Ruttan T, Allison SL, Schalich J, Heinz FX, Harrison SC, Rey FA, Fuller SD. Molecular organization of a recombinant subviral particle from tick-borne encephalitis virus. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lok SM, Kostyuchenko V, Nybakken GE, Holdaway HA, Battisti AJ, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Sedlak D, Fremont DH, Chipman PR, Roehrig JT, Diamond MS, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. Binding of a neutralizing antibody to dengue virus alters the arrangement of surface glycoproteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:312–317. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis JK, Bothner B, Smith TJ, Siuzdak G. Antiviral agent blocks breathing of the common cold virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U.S.A. 1998;95:6774–6778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kostyuchenko VA, Chew PL, Ng TS, Lok SM. Near-atomic resolution cryo-electron microscopic structure of dengue serotype 4 virus. J. Virol. 2014;88:477–482. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02641-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sukupolvi-Petty S, Brien JD, Austin SK, Shrestha B, Swayne S, Kahle K, Doranz BJ, Johnson S, Pierson TC, Fremont DH, Diamond MS. Functional analysis of antibodies against dengue virus type 4 reveals strain-dependent epitope exposure that impacts neutralization and protection. J. Virol. 2013;87:8826–8842. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01314-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]