Abstract

In Caenorhabditis elegans, males have one X chromosome and hermaphrodites have two. Emerging evidence indicates that the male X is transcriptionally more active than autosomes to balance the single X to two sets of autosomes. Because upregulation is not limited to males, hermaphrodites need to strike back and downregulate expression from the two X chromosomes to balance gene expression in their genome. Hermaphrodite-specific downregulation involves binding of the dosage compensation complex to both Xs. Advances in recent years revealed that the action of the dosage compensation complex results in compaction of the X chromosomes, changes in the distribution of histone modifications, and ultimately limiting RNA Polymerase II loading to achieve chromosome-wide gene repression.

Introduction

Dosage compensation balances the gene expression of the X and autosomes while equalizing sex chromosome-linked gene expression levels between the sexes. Recent genomic analyses of gene expression uncovered evidence for the presence of dosage compensation in some organisms and evidence for the absence, or incomplete nature, of dosage compensation in others [1]. The three mechanistically best understood examples of chromosome-wide dosage compensation include the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, and mammals (especially mice and humans).

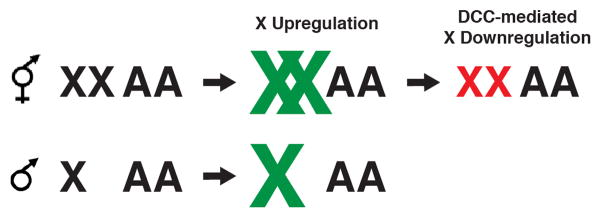

In Caenorhabditis elegans, males have one X chromosome, and hermaphrodites have two. The ratio of X chromosomes to autosomes (X:A ratio), regulates both sexual fate and dosage compensation through a complex molecular chromosome counting mechanism [2]. Dosage compensation in this organism is believed to involve two mechanisms. First, upregulation of the X chromosome balances X-linked gene expression levels to autosomes in males [3,4]. However, unlike in the fruit fly, where upregulation is limited to males, in C. elegans the X chromosomes appear to be upregulated also in hermaphrodites. This upregulation leads to overexpression of the Xs, necessitating the second mechanism: downregulation of both X chromosomes by a factor of two [5] (Figure 1). Research in the past few years focused on elucidating the mechanism of the hermaphrodite-specific X-downregulation, mediated by the dosage compensation complex (DCC). However, some studies also provided hints as to the mechanism of X-upregulation.

Figure 1. Regulation of the X chromosomes in Caenorhabditis elegans.

Although the mechanism of upregulation is not known, it is believed that the X chromosomes in C. elegans are transcriptionally more active than the autosomes (green X chromosomes). X-upregulation balances the single X to two sets of autosomes in males, but creates X overexpression in hermaphrodites. A second, and better understood, mechanism then downregulates both X chromosomes by half, to restore genomic balance in hermaphrodites (red X chromosomes).

The dosage compensation complex

The DCC binds along the length of both hermaphrodite X chromosomes to downregulate gene expression [5]. Most components of the DCC were originally identified in genetic screens for sex-specific phenotypes [6–12]. Since X-repression is hermaphrodite-specific, but X-upregulation is thought to occur in both sexes, by design, these screens would identify components of the DCC, but not the X-upregulation machinery. Additional subunits were identified by nature of their biochemical interaction with known DCC components [13,14].

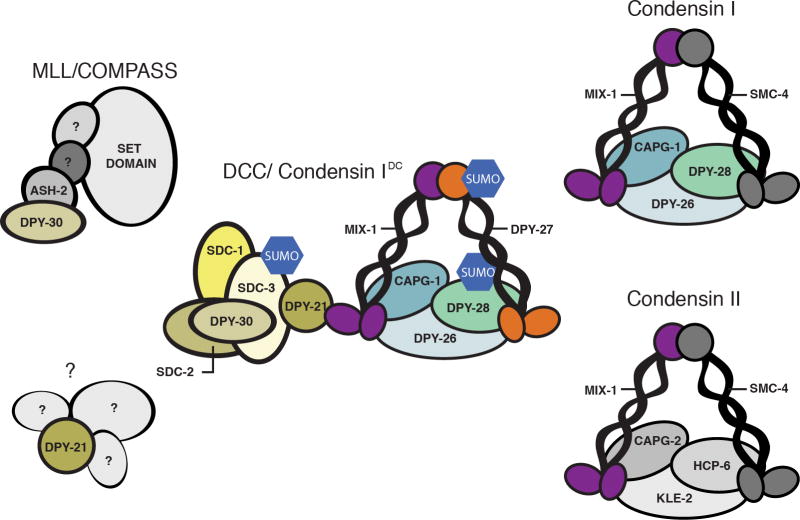

The DCC contains a five-subunit condensin complex, condensin IDC [13–18], and five associated proteins [19–23] (Figure 2). Condensin complexes function to compact and segregate chromosomes during mitosis and meiosis [24]. Condensin IDC appears to be a bona fide condensin. In fact it shares several subunits with mitotic condensins (Figure 2) [13,17]. Yet it differs from canonical condensins in both chromosome-specificity and cell cycle specificity of function [13,17]. Additional non-condensin DCC members, notably SDC-2, DPY-30, and SDC-3, dictate chromosome specificity of DCC binding [19,21,22]. Some additional DCC members also function outside dosage compensation. DPY-30 functions as part of the histone methyltransferase complex COMPASS/MLL [22], and DPY-21 regulates growth and metabolism downstream of TOR complex 2 both in the context of the DCC and independently of it [*25] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The dosage compensation complex (DCC).

The DCC consists of a five subunit condensin complex, as well as at least five additional subunits. Several of its subunits are also members of other complexes and perform DCC-independent functions as well. Condensin IDC shares four of its five subunits with condensin I, and one subunit with condensin II. Several DCC subunits need to be sumoylated. In case of dual function subunits, such as DPY-28, the protein is only sumoylated when part of the DCC. DPY-30, in addition to interacting with several DCC members, is also part of the COMPASS/MLL histone methyltransferase complex. DPY-21 has both DCC-dependent and DCC-independent functions, although the context of its DCC-independent function is not known.

Robust X-chromosome specific binding of the DCC also requires sumoylation of several subunits, SDC-3, DPY-27 and DPY-28 [*26]. DPY-28 also functions in the context of condensin I, but it is only sumoylated when part of the DCC (Figure 2). Depletion of SUMO reduced X chromosome binding of condensin IDC, but not binding of SDC-2 and DPY-30, indicating that sumoylation is needed for stable interaction between X targeting proteins and other DCC members, rather than initial X recognition [*26]. Interestingly, SUMO depletion also leads to the appearance of novel DCC binding sites on autosomes [*26], suggesting that while SUMO may be required to restrict DCC binding to the X chromosome. This latter interpretation is similar to a previous finding, where restriction of DCC binding to the X chromosome required the histone variant HTZ-1 [27]. Whether DCC restriction to the X is through sumoylation of a DCC subunit or some other protein is not known.

DCC-mediated changes in chromatin structure and compaction

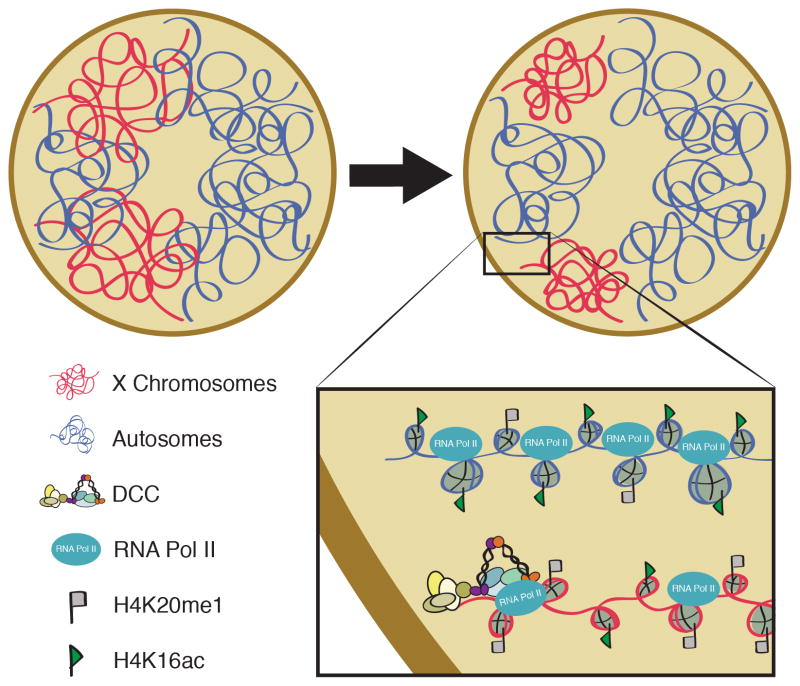

The similarity of condensin IDC to mitotic condensin suggests that repression of the X chromosome may be mediated by a mechanism similar to mitotic chromosome condensation. Although this was suggested decades ago [15], experimental evidence only emerged recently. Chromosome volume measurements demonstrated that the DCC compacts the X chromosomes (Figure 3) [**28]. While the X chromosome represents 18% of the genome in hermaphrodites, physically it occupies only about 10% of the nuclear volume. When the DCC is not present, the X decompacts to its expected size. These results are consistent with the general idea that more compact chromatin represses transcription.

Figure 3. Summary of DCC-mediated changes in chromatin and chromosome compaction.

As a result of DCC function, the X chromosomes (shown in red) in hermaphrodites compact to take up a smaller portion of the nucleus than what would be predicted by DNA content. Compaction is accompanied by enrichment of H4K20me1 (gray flags) and depletion of H4K16ac (green flags). These changes are consistent with a mechanism related to mitotic chromosome condensation.

The DCC modifies the X chromatin at the level of nucleosome structure as well. Interestingly, the modifications acquired by the dosage compensated X mirror changes that occur at mitosis. The dosage compensated X is enriched for monomethylation of H4 lysine 20 (H4K20me1) [*29,*30] and is depleted of H4 lysine 16 acetylation (H4K16Ac) compared to autosomes [*30] (Figure 3). These changes are also seen on mitotic chromosomes [31–33]. X-chromosome enrichment of H4K20me1 requires not only the activity of the DCC, but also the activities of SET-1 (homolog of H4K20 monomethylase Pr-Set7) and SET-4 (homolog of H4K20 di-and trimethylase Suv4-20h1/h2) [*29,*30]. In mammals, levels of both Pr-Set7 and H4K20me1 increase in G2, remain high in mitosis, then decline in G1, suggesting that this modification functions in mitosis [31,32]. Two condensin II subunits can directly bind to an H4 tail peptide monomethylated at K20, suggesting a role for this modification in condensin II loading [34]. Thus, a link between condensin and H4K20me1 is suggested both in mitosis and in dosage compensation, although in mitosis H4K20me1 is proposed to recruit condensin (II), while in dosage compensation, a condensin I-like complex is required for the X-enrichment of H4K20me1.

Interestingly, dosage compensation appears disrupted both in set-1 mutants (which lack H4K20me1) and in set-4 mutants (which have higher than normal level of H4K20me1 evenly distributed across the nucleus) [*25,30]. These results suggest that it is not H4K20me1 per se that is required for dosage compensation, but rather a difference in H4K20me1 levels between the X and the autosomes. This interpretation is also consistent with earlier gene expression studies which showed that defects in DCC activity lead to an increase in X-linked gene expression and a decrease in autosomal gene expression [35]. These observations evoke a balancing act between the X and the autosomes, rather than a regulatory process limited to the X chromosomes.

Enrichment of H4K20me1 on the X chromosomes can be achieved by a DCC-dependent increase in SET-1 activity or reduction SET-4 activity on the X, or a combination of both. These different models make different predictions as to the changes in global H4K20me1 levels in DCC mutants. Two studies that addressed this question obtained conflicting results [*25,*29], and therefore the question of how the DCC influences SET-1 and SET-4 activities remains open. Another unexplored possibility is that an H4K20 demethylase activity [34] also contributes to the process.

H4K20me1 antagonizes H4K16ac [36]. It is therefore not surprising that H4K16ac is depleted on dosage compensated X chromosomes [*30]. This depletion depends not only on the DCC and the histone deacetylase SIR-2.1, but also on the activities of SET-1 and SET-4. Thus, H4K20me1 levels do in fact influence H4K16ac levels in the context of dosage compensation. However, the reverse is not true; changes in H4K16ac do not result in perturbation of the X-enrichment of H4K20me1, suggesting that H4K20me1 acts upstream of H4K16ac [*30]. Both enrichment of H4K20me1 and depletion of H4K16ac appear to contribute to compaction of the dosage compensated X chromosomes, since the X appears decompacted in set-1, set-4 and sir-2.1 mutants [**28]. However, while set-1 and set-4 depletion is sufficient to rescue males that inappropriately activate the DCC (and consequently die of insufficient X chromosome expression), sir-2.1 is not [*30], indicating that the gene expression changes caused by the lack of set-1 or set-4 are more significant than the changes caused by lack of sir-2.1. One possible explanation is that low levels of H4K16ac may be a consequence, rather than a cause, of differences in gene expression. In addition, H4K20me1 influences other aspects of chromosome dynamics. For example, L3MBTL1 was shown to drive chromatin compaction via interactions with H4K20me1 [37].

DCC-mediated changes in transcription

Repression by the DCC ultimately leads to a decrease in X-linked transcript levels [9]. In dosage compensation mutants, the increase in X-linked mRNA levels is accompanied by a decrease in autosome-linked mRNA levels [35]. Consistent with that, ChIP-chip experiments in these mutants revealed an increased level of RNA Polymerase II (Pol II) occupancy on X-linked [22]. To determine which step in transcription is regulated, a recent study mapped transcriptionally engaged Pol II using global run-on sequencing (GRO-seq) and defined transcription start sites using a modified form of GRO-seq to enrich for RNAs with a 5’-cap (GRO-cap) [**38]. GRO-seq revealed a uniform increase in transcriptionally engaged Pol II along the gene bodies of X-linked genes in dosage compensation mutants, suggesting that dosage compensation restricts either recruitment or initiation of Pol II. An increase in hypophosphorylated (uninitiated) Pol II at transcription start sites further suggested that the predominant step of regulation is recruitment [**38] (Figure 3).

Evidence for X-upregulation

Ohno argued in 1967 that the X chromosome in monogametic males needs to be upregulated to create a genomic balance between the X and autosomes [39]. It was not until decades later that experimental evidence emerged to support this hypothesis in C. elegans [3,4]. These studies showed that the average gene expression level from the single male X appears comparable to the average gene expression level from autosomes. A recent study found evidence both for and against X-upregulation in three additional nematode species [*40]. When they limited analysis to highly expressed genes (to exclude germline-repressed genes), all chromosomes, including the X, showed comparable levels of gene expression in both males and females/hermaphrodites, supporting the X-upregulation hypothesis. However, analysis of a limited number of one-to-one orthologs located on the X in one species and on an autosome in another indicated that the autosomal ortholog is expressed at a higher level, arguing against X-upregulation [*40]. Perhaps X-upregulation is not complete and is limited to a subset of X-linked genes.

The GRO-seq studies described above confirmed that the X chromosomes in DCC mutant hermaphrodites are more transcriptionally active than the autosomes [**38]. In wild type hermaphrodites, levels of transcriptionally engaged Pol II on the X chromosomes (postulated to be subjected to both upregulation and downregulation) are equivalent to levels on autosomes. Furthermore, in dosage compensation mutant hermaphrodites, levels of engaged Pol II on the X (subject to upregulation only) are elevated compared to autosomes [**38]. Males were not analyzed in this study.

Consistent with X-upregulation in males, chromosome volume measurements suggest that the male X is unexpectedly decondensed [**28]. The model summarized in Fig. 1 predicts that the volume of the single male X should be half of the two Xs in DCC mutant hermaphrodites. However, measurements showed that the male X occupies an even larger area of the nucleus, suggesting that the males X is different from the Xs in DCC mutant hermaphrodites [**28]. One possibility is that DCC depletions were incomplete in this study, leading to less than maximal decondensation in hermaphrodites. However, levels of decondensation were remarkably consistent between different DCC depletions and mutants, arguing against this possibility [**28]. A similar difference between the male X and the DCC-depleted hermaphrodite X was also observed with respect to H4K16ac levels [*30]. While wild type hermaphrodite X chromosomes are depleted of H4K16ac, DCC mutant hermaphrodite X chromosomes are enriched for this modification, as observed by fluorescent microscopy. High levels of H4K16ac are consistent with an upregulated state. However, this enrichment was not observed on the male X chromosome [*30]. An alternative possibility is that DCC activity is not the only difference between male and hermaphrodite X chromosomes, and additional sex- or karyotype-specific disparities exist, perhaps regulated by a feedback loop between sex determination and dosage compensation [6,41–43].

The onset of dosage compensation

Establishment of dosage compensation is a multistep process. Interestingly, there is no evidence of X-upregulation temporarily preceeding X-downregulation, and thus representing a “first” step prior to the “second” downregulation step. In fact, the X in early embryos, both male and hermaphrodite, appears underacetylated (suggesting that it is hypotranscribed) compared to autosomes [*44]. The X chromosome is enriched for genes which are not turned on until the 40–60 cell stage in development [45], the same time when the DCC assembles on the X chromosomes [21]. Thus, there does not appear to be a time in wild type hermaphrodite development when the X is hypertranscribed and needs to be downregulated. Instead, the two processes may be initiated simultaneously. Consistently, the X in male embryos appear to transition from a hypoacetylated state to a presumably hypertranscribed state at about this time in development, although the exact timing is hard to pinpoint without better molecular markers [*44].

The time window in which dosage compensation initiates [21]is also coincides with the onset of gastrulation [46]. Prior to this stage, embryonic blastomeres can be forced to adapt alternate cell fates by expression of a developmental regulator, but after this transition they cannot [47–52]. Timing of this transition from plasticity to differentiation is under the control of the Polycomb-like complex made up of MES-2, MES-3 and MES-6 [53]. In mes mutants, both the transition from plasticity to differentiation [53] and the onset of dosage compensation are delayed [*44]. The onset of dosage compensation is linked to differentiation in mammals as well [54], indicating that this link might be universal.

Another similarity between the various dosage compensation systems is the stepwise nature of the appearance of the different chromatin features associated with dosage compensation. In C. elegans, the DCC assembles on the X chromosomes at about the 30-cell stage [21], but H4K20me1 enrichment does not appear until much later, around the comma stage [*29,*44]. By this time, the C. elegans embryo consists of about 600 cells, and most cells have stopped cycling [46]. What exactly triggers the timing of DCC localization and the timing of H4K20me1 accumulation on X remains to be determined.

Using temperature sensitive alleles of DCC components, the critical window of DCC action was defined as a 4–5 hour time window centered around the comma stage [11]—significantly, the time window when DCC mediated chromatin marks are being established [*29,*44]. The observation that temperature shifts after this time period have less of an effect on viability suggests that once dosage compensation is established, the DCC becomes dispensable. However, recent studies established postembryonic roles for the DCC in the regulation of dauer arrest [*55], indicating that DCC-mediated regulation of X-linked genes continues to be important for normal development post-embryogenesis.

Conclusions and future directions

Despite recent advances, many questions remain. It is not known how the described changes in chromatin structure influence RNA Pol II activity. Additionally, the severity of chromatin changes does not correlate with the severity of dosage compensation defects in the various mutants [*30], indicating that the DCC likely contributes to dosage compensation in other ways. It is interesting to note that condensin II subunits in Drosophila and mammalian cells were found to colocalize with other architectural proteins at boundaries of topologically associating domains (TADs), suggesting that these proteins may cooperate in shaping the interphase genome at the level of TAD organization [56]. In C. elegans interphase nuclei, condensin II sites showed a significant overlap with condensin IDC sites on the X chromosomes [57], raising the possibility that condensing IDC and condensin II might cooperate in shaping the interphase structure of the dosage compensated X chromosome.

The main question of how DCC-mediated changes in the structure of the X chromosomes lead to changes in RNA Polymerase recruitment remains unresolved. DCC binding to a gene is neither necessary, nor sufficient, for transcriptional regulation. DCC binding correlates with Pol II occupancy, but does not predict dosage compensation status [35,**38]. These results suggest that the DCC is not directly regulating bound genes, but rather is acting at a distance. The rules of which genes are to be regulated and which ones are not remain to be deciphered.

Acknowledgments

Research in our laboratory is funded by the National Institute of Health (grant GM079533) to G.C. The authors would like to thank Martha Snyder for critical reading of the manuscript, and members of the Csankovszki laboratory for discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Alyssa C. Lau, Email: aclau@umich.edu.

Györgyi Csankovszki, Email: gyorgyi@umich.edu.

References

- 1.Mank JE. Sex chromosome dosage compensation: definitely not for everyone. Trends Genet. 2013;29:677–683. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farboud B, Nix P, Jow MM, Gladden JM, Meyer BJ. Molecular antagonism between X-chromosome and autosome signals determines nematode sex. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1159–1178. doi: 10.1101/gad.217026.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng X, Hiatt JB, Nguyen DK, Ercan S, Sturgill D, Hillier LW, Schlesinger F, Davis CA, Reinke VJ, Gingeras TR, et al. Evidence for compensatory upregulation of expressed X-linked genes in mammals, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ng.948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta V, Parisi M, Sturgill D, Nuttall R, Doctolero M, Dudko OK, Malley JD, Eastman PS, Oliver B. Global analysis of X-chromosome dosage compensation. J Biol. 2006;5:3. doi: 10.1186/jbiol30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer BJ. Targeting X chromosomes for repression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLong L, Plenefisch JD, Klein RD, Meyer BJ. Feedback control of sex determination by dosage compensation revealed through Caenorhabditis elegans sdc-3 mutations. Genetics. 1993;133:875–896. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.4.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodgkin J. X chromosome dosage and gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans: Two unusual dumpy genes. Mol Gen Genet. 1983;192:452–458. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu DR, Meyer BJ. The dpy-30 gene encodes an essential component of the Caenorhabditis elegans dosage compensation machinery. Genetics. 1994;137:999–1018. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.4.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer BJ, Casson LP. Caenorhabditis elegans compensates for the difference in X chromosome dosage between the sexes by regulating transcript levels. Cell. 1986;47:871–881. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nusbaum C, Meyer BJ. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene sdc-2 controls sex determination and dosage compensation in XX animals. Genetics. 1989;122:579–593. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.3.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plenefisch JD, DeLong L, Meyer BJ. Genes that implement the hermaphrodite mode of dosage compensation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1989;121:57–76. doi: 10.1093/genetics/121.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villeneuve AM, Meyer BJ. sdc-1: a link between sex determination and dosage compensation in C. elegans. Cell. 1987;48:25–37. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90352-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Csankovszki G, Collette K, Spahl K, Carey J, Snyder M, Petty E, Patel U, Tabuchi T, Liu H, McLeod I, et al. Three distinct condensin complexes control C. elegans chromosome dynamics. Curr Biol. 2009;19:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieb JD, Albrecht MR, Chuang PT, Meyer BJ. MIX-1: an essential component of the C. elegans mitotic machinery executes X chromosome dosage compensation. Cell. 1998;92:265–277. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80920-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chuang PT, Albertson DG, Meyer BJ. DPY-27:a chromosome condensation protein homolog that regulates C. elegans dosage compensation through association with the X chromosome. Cell. 1994;79:459–474. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieb JD, Capowski EE, Meneely P, Meyer BJ. DPY-26, a link between dosage compensation and meiotic chromosome segregation in the nematode. Science. 1996;274:1732–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mets DG, Meyer BJ. Condensins regulate meiotic DNA break distribution, thus crossover frequency, by controlling chromosome structure. Cell. 2009;139:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai CJ, Mets DG, Albrecht MR, Nix P, Chan A, Meyer BJ. Meiotic crossover number and distribution are regulated by a dosage compensation protein that resembles a condensin subunit. Genes Dev. 2008;22:194–211. doi: 10.1101/gad.1618508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu DS, Dawes HE, Lieb JD, Chan RC, Kuo AF, Meyer BJ. A molecular link between gene-specific and chromosome-wide transcriptional repression. Genes Dev. 2002;16:796–805. doi: 10.1101/gad.972702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis TL, Meyer BJ. SDC-3 coordinates the assembly of a dosage compensation complex on the nematode X chromosome. Development. 1997;124:1019–1031. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.5.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawes HE, Berlin DS, Lapidus DM, Nusbaum C, Davis TL, Meyer BJ. Dosage compensation proteins targeted to X chromosomes by a determinant of hermaphrodite fate. Science. 1999;284:1800–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pferdehirt RR, Kruesi WS, Meyer BJ. An MLL/COMPASS subunit functions in the C. elegans dosage compensation complex to target X chromosomes for transcriptional regulation of gene expression. Genes Dev. 2011;25:499–515. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yonker SA, Meyer BJ. Recruitment of C. elegans dosage compensation proteins for gene-specific versus chromosome-wide repression. Development. 2003;130:6519–6532. doi: 10.1242/dev.00886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirano T. Condensins: universal organizers of chromosomes with diverse functions. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1659–1678. doi: 10.1101/gad.194746.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *25.Webster CM, Wu L, Douglas D, Soukas AA. A non-canonical role for the C. elegans dosage compensation complex in growth and metabolic regulation downstream of TOR complex 2. Development. 2013;140:3601–3612. doi: 10.1242/dev.094292. In addition to characterizing the biological significance of DCC function in a specific context, this paper also provided independent evidence for the imporatnce of SET-4. The study also demonstrated that DPY-21, a DCC member, regulates this process in males, independent of other DCC members. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *26.Pferdehirt RR, Meyer BJ. SUMOylation is essential for sex-specific assembly and function of the Caenorhabditis elegans dosage compensation complex on X chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E3810–3819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315793110. This is the first study that addresses posttranslational modifications of the DCC. The results support the hypothesis that sumoylation of several DCC subunits helps assemble the complex on the X chromosome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petty EL, Collette KS, Cohen AJ, Snyder MJ, Csankovszki G. Restricting dosage compensation complex binding to the X chromosomes by H2A. Z/HTZ-1. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **28.Lau AC, Nabeshima K, Csankovszki G. The C. elegans dosage compensation complex mediates interphase X chromosome compaction. Epigenetics and Chromatin. (in press). This study tested a long-standing hypothesis that the DCC induced compaction of the X chromosomes. The results demonstrate that the volume occupied by DCC-bound X chromosomes is in fact smaller than predicted by DNA content, strengthening the link between dosage compensation and mitotic chromosome compaction. [Google Scholar]

- *29.Vielle A, Lang J, Dong Y, Ercan S, Kotwaliwale C, Rechtsteiner A, Appert A, Chen QB, Dose A, Egelhofer T, et al. H4K20me1 contributes to downregulation of X-linked genes for C. elegans dosage compensation. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002933. Together with [*30], this study demonstrated that DCC function results in an enrichment of H4K20me1 on the X chromosomes. The authors propose that this mitosis-linked histone modification contributes to X repression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *30.Wells MB, Snyder MJ, Custer LM, Csankovszki G. Caenorhabditis elegans dosage compensation regulates histone H4 chromatin state on X chromosomes. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:1710–1719. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06546-11. Together with [*29], this study demonstrated that DCC function leads to enrichment of H4K20me1 on the X, They further showed that as a result, H4K16ac is depleted. These modifications are thought to contribute to, or result from, DCC-mediated repression. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oda H, Okamoto I, Murphy N, Chu J, Price SM, Shen MM, Torres-Padilla ME, Heard E, Reinberg D. Monomethylation of histone H4-lysine 20 is involved in chromosome structure and stability and is essential for mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2278–2295. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01768-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rice JC, Nishioka K, Sarma K, Steward R, Reinberg D, Allis CD. Mitotic-specific methylation of histone H4 Lys 20 follows increased PR-Set7 expression and its localization to mitotic chromosomes. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2225–2230. doi: 10.1101/gad.1014902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkins BJ, Rall NA, Ostwal Y, Kruitwagen T, Hiragami-Hamada K, Winkler M, Barral Y, Fischle W, Neumann H. A cascade of histone modifications induces chromatin condensation in mitosis. Science. 2014;343:77–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1244508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu W, Tanasa B, Tyurina OV, Zhou TY, Gassmann R, Liu WT, Ohgi KA, Benner C, Garcia-Bassets I, Aggarwal AK, et al. PHF8 mediates histone H4 lysine 20 demethylation events involved in cell cycle progression. Nature. 2010;466:508–512. doi: 10.1038/nature09272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jans J, Gladden JM, Ralston EJ, Pickle CS, Michel AH, Pferdehirt RR, Eisen MB, Meyer BJ. A condensin-like dosage compensation complex acts at a distance to control expression throughout the genome. Genes Dev. 2009;23:602–618. doi: 10.1101/gad.1751109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishioka K, Rice JC, Sarma K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Werner J, Wang Y, Chuikov S, Valenzuela P, Tempst P, Steward R, et al. PR-Set7 is a nucleosome-specific methyltransferase that modifies lysine 20 of histone H4 and is associated with silent chromatin. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00548-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trojer P, Li G, Sims RJ, 3rd, Vaquero A, Kalakonda N, Boccuni P, Lee D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Nimer SD, et al. L3MBTL1, a histone-methylation-dependent chromatin lock. Cell. 2007;129:915–928. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **38.Kruesi WS, Core LJ, Waters CT, Lis JT, Meyer BJ. Condensin controls recruitment of RNA polymerase II to achieve nematode X-chromosome dosage compensation. Elife. 2013;2:e00808. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00808. Due to the poor annotation of transcription starts sites in C. elegans (as a consequence of trans-splicing), studying transcription initiation has been hard. This study used GRO-cap to map transcription start sites and used this information, together with GRO-seq data, to determine that the most likely step of regulation is RNA Polymerase II recruitment to transcription start sites. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohno S. Sex chromosomes and sex-linked genes. Vol. 1. Berlin: Spinger; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- *40.Albritton SE, Kranz AL, Rao P, Kramer M, Dieterich C, Ercan S. Sex-Biased Gene Expression and Evolution of the X Chromosome in Nematodes. Genetics. 2014;197:865–883. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.163311. RNA-seq analysis of several nematode species provided evidence both for and against X-upregulation. The study also looked at how the dosage imbalance between XO and XX individuals contributes to shaping the gene content of the X chromosomes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berkseth M, Ikegami K, Arur S, Lieb JD, Zarkower D. TRA-1 ChIP-seq reveals regulators of sexual differentiation and multilevel feedback in nematode sex determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16033–16038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312087110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hargitai B, Kutnyanszky V, Blauwkamp TA, Stetak A, Csankovszki G, Takacs-Vellai K, Vellai T. xol-1, the master sex-switch gene in C. elegans, is a transcriptional target of the terminal sex-determining factor TRA-1. Development. 2009;136:3881–3887. doi: 10.1242/dev.034637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hodgkin J. Exploring the envelope. Systematic alteration in the sex-determination system of the nematode caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2002;162:767–780. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.2.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *44.Custer LM, Snyder MJ, Flegel K, Csankovszki G. The onset of C. elegans dosage compensation is linked to the loss of developmental plasticity. Dev Biol. 2014;385:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.11.001. This study looked at how the onset of dosage compensation is regulated by analyzing the timing of DCC-mediated chromatin changes. There is no evidence for an “initial” upregulation step followed by a “second” downregulation step. Rather, the two processes may occur simultaneously. In addition, the onset of dosage compensation appears to be linked to the loss of developmental plasticity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baugh LR, Hill AA, Slonim DK, Brown EL, Hunter CP. Composition and dynamics of the Caenorhabditis elegans early embryonic transcriptome. Development. 2003;130:889–900. doi: 10.1242/dev.00302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukushige T, Krause M. The myogenic potency of HLH-1 reveals widespread developmental plasticity in early C. elegans embryos. Development. 2005;132:1795–1805. doi: 10.1242/dev.01774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilleard JS, McGhee JD. Activation of hypodermal differentiation in the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo by GATA transcription factors ELT-1 and ELT-3. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2533–2544. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2533-2544.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horner MA, Quintin S, Domeier ME, Kimble J, Labouesse M, Mango SE. pha-4, an HNF-3 homolog, specifies pharyngeal organ identity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1947–1952. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joshi PM, Riddle MR, Djabrayan NJ, Rothman JH. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for stem cell biology. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:1539–1554. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quintin S, Michaux G, McMahon L, Gansmuller A, Labouesse M. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene lin-26 can trigger epithelial differentiation without conferring tissue specificity. Dev Biol. 2001;235:410–421. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu J, Fukushige T, McGhee JD, Rothman JH. Reprogramming of early embryonic blastomeres into endodermal progenitors by a Caenorhabditis elegans GATA factor. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3809–3814. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuzyuk T, Fakhouri TH, Kiefer J, Mango SE. The polycomb complex protein mes-2/E(z) promotes the transition from developmental plasticity to differentiation in C. elegans embryos. Dev Cell. 2009;16:699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Navarro P, Chambers I, Karwacki-Neisius V, Chureau C, Morey C, Rougeulle C, Avner P. Molecular coupling of Xist regulation and pluripotency. Science. 2008;321:1693–1695. doi: 10.1126/science.1160952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *55.Dumas KJ, Delaney CE, Flibotte S, Moerman DG, Csankovszki G, Hu PJ. Unexpected role for dosage compensation in the control of dauer arrest, insulin-like signaling, and FoxO transcription factor activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2013;194:619–629. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.149948. Earlier studies established that the crucial time window for DCC function is around the comma stage in embryogenesis. This study demonstrated a specific postembryonic role for the DCC in regulating dauer arrest. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Bortle K, Nichols MH, Li L, Ong CT, Takenaka N, Qin ZS, Corces VG. Insulator function and topological domain border strength scale with architectural protein occupancy. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R82. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-5-r82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kranz AL, Jiao CY, Winterkorn LH, Albritton SE, Kramer M, Ercan S. Genome-wide analysis of condensin binding in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R112. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]