Abstract

Introduction

Rosacea (including facial erythema) has a negative impact on psychological and emotional health. This survey aimed to assess the impact of facial erythema on subconscious perceptions and the initial reactions of others and how this affects attitudes in different settings. The survey also measured the impact of facial erythema on a person’s emotional and psychological wellbeing.

Methods

A total of 6831 participants from eight countries completed online computer-assisted web interviewing psychological assessments based on the implicit association test. Traditional questionnaires provided data on the impact of facial erythema and perceptions of people with rosacea from other participants.

Results

Facial erythema was strongly associated with poor health and negative personality traits with participants reporting negative impacts of rosacea emotionally, socially and in the workplace. Nearly 80% reported difficulty in controlling facial erythema but those with physician-diagnosed rosacea had significantly improved control versus those with undiagnosed rosacea (39% vs 20%, p < 0.05).

Conclusions

People with facial erythema have to manage their own psychological barriers to cope with the disease and deal with the prejudice and negative first impressions of others. Formal diagnosis, advice and treatment from a healthcare professional improve rosacea control.

Funding

Galderma.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0077-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Attitudes, Diagnosis, Emotional, Facial erythema, Perceptions, Psychological, Quality of life, Rosacea, Social, Skin

Introduction

Rosacea is a chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disease with a reported variable prevalence of 2.2%, 10% and 22% depending on the study population and setting [1–3]. It is commonly estimated to affect about one in 10 people in the general population [4, 5]. Common signs and symptoms include persistent facial erythema, flushing, telangiectasia, inflammatory papules and pustules, edema and eye symptoms [6, 7].

Facial erythema is commonly found among the four clinical subtypes of the condition (erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous and ocular manifestations) and for many is a prominent and visible hallmark of the condition [8]. The erythema associated with rosacea commonly takes a distinct, characteristic pattern affecting mainly the convexities of the face including cheeks, nose, chin and central forehead [8] but rosacea is generally underdiagnosed and often overlooked [2, 9].

A number of studies in the psychodermatological literature show that skin disorders have a negative impact on the psychological and emotional health of some of those affected [10]. These effects include depression, a decreased sense of body image and self-esteem, sexual and relationship difficulties and a general reduction in quality of life [11–14].

In addition to these psychosocial effects, people with visible dermatological conditions often face stigmatization with many claiming their difficulties arise from others’ reaction to their disease rather than the disease itself [15]. These reactions can have a profound psychological impact, sometimes to the point of being traumatic [10].

There is evidence that people hold negative implicit attitudes (attitudes that have not been modified in response to social desirability) toward people with visible skin conditions [16], potentially compounding negative self-perceptions [17].

Rosacea can be particularly troubling for self-perception as flare-ups can be triggered or exacerbated by emotional stress with the visible redness creating further distress. The condition has been associated with anxiety, avoidance of social settings and emotional suffering [9, 18]. A recent systematic review demonstrates that rosacea has a negative impact on health-related quality of life [19]. The impact of rosacea on quality of life is reflected in the substantial amount of money patients in the US are willing to pay to reduce their symptoms [20].

Primary Objective

The Face Values: Global Perceptions Survey aimed primarily to assess the impact of facial erythema associated with rosacea on the subconscious perceptions and initial reactions of others, including those affected by the condition. It assessed how these perceptions may affect their attitudes and choices about people with rosacea in relation to work, in relationships and in general social settings. This approach builds on a previous US study in people who had signs of mild to moderate papular/pustular rosacea and which highlighted consistent differences in attitudes toward those with rosacea versus images of people with clear skin (Kelton Research 2009, data on file).

Secondary Objective

The second aim of the survey was to measure the impact of facial erythema on emotional and psychological wellbeing and to better understand the personal experiences of living with facial erythema associated with rosacea.

Methods

This international survey consisted of self-completed questionnaires with 6831 participants aged 25–64 in eight countries (Germany, UK, Ireland, Sweden, Denmark, France, Italy and Mexico) recruited from established online general population research panels. There were a total of 93,275 potential people invited to participate in the survey. Of those, 13,325 responded and 1647 were screened out as being out of scope of the survey (i.e., being under 25 years or over 65 years old). 987 started but did not complete the survey (these data were not analyzed). 6831 completed the survey and 3861 were over quota.

Quotas were set by age, gender and geographic region to ensure reliable and accurate representation of the population from each country. A minimum of 1000 interviews were conducted in larger markets of Germany, France, Mexico and UK and 500 in those with smaller populations (Denmark, Ireland and Sweden). It was assumed that this number of interviews would ensure a minimum base of rosacea sufferers in each country. Margin of error was calculated at the 95% confidence interval level. The sample size provides a margin of error of ±1.57% at the global level, breaking down at between ±3.05% (France) and ±4.34% (Denmark) for each individual country.

All participants completed the questions using online computer-assisted web interviewing. This comprised a psychological assessment (Emotix©) based on the implicit association test designed to capture respondents’ attitudes and emotions to reduce response bias [21]. The Emotix assessment was followed by a standard online questionnaire adapted from the one used in previous research (Kelton Research 2009, data on file). The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into native language of each participating country: Danish (Denmark), French (France), German (Germany), Spanish (Mexico) and Swedish (Sweden). The UK and Ireland questionnaire was conducted in English. The terminology, question order and semantics of the questionnaire were reviewed by chartered psychometric psychologists. The final questionnaire was the final edit of the work of these specialists and was reviewed by Bryter, as independent market research consultants.

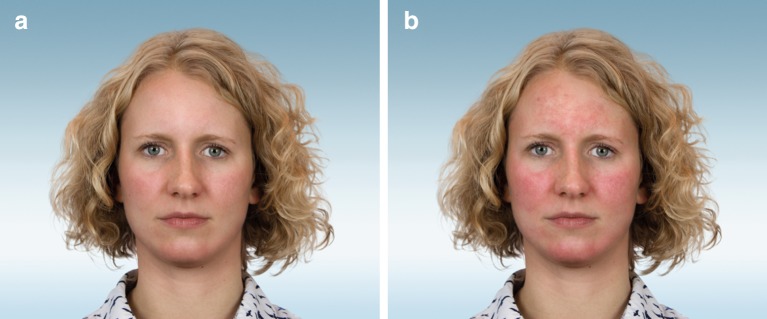

During the assessment, participants were shown images of people with and without facial erythema who were representative of their region (i.e., Northern Europe, Southern Europe, Latin America). The models used did not suffer from facial erythema but the images were digitally altered to portray the typical facial redness associated with rosacea (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Examples of images shown to respondents. a Northern European female image without facial erythema. b Northern European female image with facial erythema

For the Emotix assessment, participants were asked to associate or discard words shown next to each image (for example, ‘trustworthy’, ‘relaxed’, ‘healthy’, ‘tired’), with the speed of their response directly linked to their initial, subconscious perception of the face appearing on screen (Supplementary Appendix Figure 1). This yielded quantitative and qualitative data that could be analyzed and interpreted at different levels of complexity.

Following the Emotix test, participants also completed a traditional questionnaire to ascertain comparative attitudes toward further images of facial erythema associated with rosacea versus non-affected images (Supplementary Appendix Figure 2). In addition, all participants who self-reported facial erythema at screening were requested to answer a further set of questions about their views of living with the condition and how it impacts on various aspects of daily life including their emotional and psychological wellbeing. As facial erythema may have a range of causes, participants who self-reported they had rosacea had to fulfill the following criteria: experience facial redness or longer lasting redness (typically brought about by factors such as spicy foods, alcohol, temperature changes, stress, and/or nervousness in public situations), accompanied by facial hotness or warmth and/or facial dryness and/or facial soreness and stinging, at least once a week. Those whose facial redness had been diagnosed by a healthcare professional as an allergic reaction or skin condition (not rosacea) were excluded.

Emotix is a scientifically robust, reliable and valid method of obtaining individuals’ otherwise unconscious attitudes, beliefs and biases (implicit social cognitions) in a number of situations such as consumer and health behavior [22–24]. In particular, it highlights the difference between so-called system 1 decision making (fast, intuitive, subconscious and emotional) and system 2 decision making (slow, considered, vetted, socially acceptable and rational) [25].

The survey was conducted by Bryter, an independent international market research consultancy, between 31 October and 18 November 2013. Participants were recruited via online panels of consumers who had signed up to take part in a variety of market research surveys. These participants are normally incentivised in a number of ways by earning points that can go toward card reward schemes.

Bryter complies with the Market Research Society Code of Conduct as well as the British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association Legal and Ethical Guidelines and requirements for the reporting of adverse events. The Emotix studies were conducted under the ethical guidelines of the British Psychological Society.

All data were analyzed using univariate analysis. Significance tests used included the proportions comparison Z test and means comparison t test. Student’s t test was used to analyze Emotix data.

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Demographics

A total of 6831 participants were enrolled from eight countries (Table 1). Of these, 50% were male and 50% were female. Recruitment achieved a representative distribution of participants across age groups (age 25–34 years [26.5%], 35–44 [27.7%], 45–54 [24.5%], 55–64 [21.3%]).

Table 1.

Number of participants from each country, and those with self-reported rosacea or diagnosed by physician

| Country | Number of participants N = 6831 | Percentage with self-reported rosacea (including physician-diagnosed rosacea) (%) | Percentage with physician-diagnosed rosacea (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 1003 | 9 | 1 |

| UK | 1006 | 15 | 2 |

| Ireland | 550 | 15 | 1 |

| Sweden | 750 | 9 | 1 |

| Denmark | 501 | 10 | 1 |

| France | 1013 | 15 | 3 |

| Italy | 1006 | 12 | 1 |

| Mexico | 1002 | 8 | 1 |

From the 6831 participants, the prevalence of self-reported rosacea in the survey was 12%, and within the range of earlier prevalence estimates [1–3]. However, approximately only one in 10 of these self-reported participants had received a definitive rosacea diagnosis by a family doctor or a dermatologist. Facial erythema associated with rosacea was more prominent in the UK, France and Ireland (15% of participants) compared to Germany and Sweden (9%) or Mexico (8%). In addition, women (15%) were more likely to identify symptoms than men (8%).

Perceptions of People with Facial Erythema Associated with Rosacea

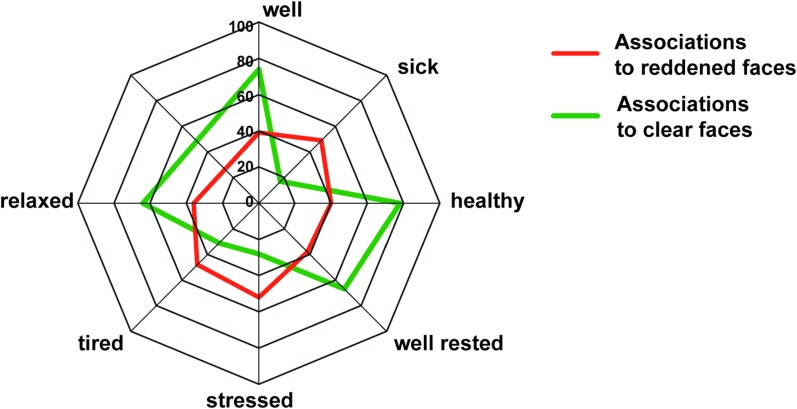

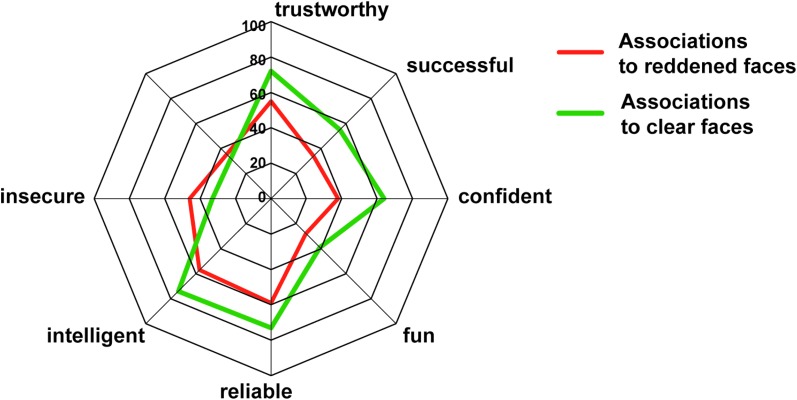

The intuitive (subconscious) word association strength of health-related words and personality-related words showed statistically significant differences when faces with erythema or no erythema were compared (Figs. 2, 3). Clear faces were strongly related to positive health and personality traits whereas facial redness was strongly associated with poor health and negative personality traits. The domains with the greatest magnitude of difference were ‘relaxed’, ‘healthy’ and ‘well’, implying that people with red faces are much more likely to be perceived as less relaxed, less healthy and less well.

Fig. 2.

A comparison of the strength of intuitive responses of health-related words associated with both clear and red facial images. A score nearer to 100 indicates a very strong intuitive association between the word and the face—while a score of 0 indicates no association. The differences in the strength of these associations between the faces are all statistically significant (p < 0.05)

Fig. 3.

A comparison of the strength of intuitive responses of personality-related words associated with both clear and red facial images. A score nearer to 100 indicates a very strong intuitive association between the word and the face—while a score of 0 indicates no association. The differences in the strength of these associations between the faces are all statistically significant (p < 0.05)

These findings were consistent across the different nationalities; however, there were significant gender differences in five of the eight countries with females being more critical than their male counterparts.

These negative first impressions of faces with erythema were reflected in participants’ views on the person’s work and social life (Table 2). The views of sufferers and non-sufferers were found to be highly similar.

Table 2.

Participants’ views on images of people with or without facial erythema

| Image with facial erythema (%) | Image without facial erythema (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance of skin was the first thing I noticed* | 77 | 24 |

| I am likely to be friends with this person* | 58 | 71 |

| I think the person has a managerial/professional job* | 43 | 61 |

| I am likely to hire this person for a job* | 70 | 85 |

| I think it is likely this person is married or dating* | 77 | 87 |

| I think that skincare is the thing they most need to change* | 60 | 12 |

* p < 0.05

Personal Experience of Rosacea

In general, those with facial erythema were not satisfied with the appearance of their skin and felt they were judged unfairly by others (Table 3). Nearly a third of these felt that improved skin appearance would positively affect people’s first impressions of them. Over 60% agreed that their condition was embarrassing, particularly when flare-ups occur in professional situations like business meetings or job interviews.

Table 3.

Participants’ perceptions of self-image

| Participants with facial erythema (%) | Participants with no facial erythema (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Satisfied with appearance of skin* | 29 | 63 |

| Agree they are judged unfairly in people’s first impression* | 81 | 70 |

| Feel improved skin appearance would improve people’s first impressions of them* | 28 | 16 |

* p < 0.05

Two-thirds of those with facial erythema have felt an impact socially, with 36% reporting feeling uncomfortable meeting new people. Over half felt it had affected their relationships and personal life, with nearly a third feeling uncomfortable when dating. A total of 77% of subjects with facial erythema associated with rosacea reported that the appearance of their skin had an emotional impact ranging from embarrassment (46%) to feeling sad/depressed (22%).

Nearly half of participants had experienced direct reactions from other people about their facial erythema, with 15% being told they drink too much, 15% being labeled with having acne and 26% having different skincare routines being recommended to them.

Control of Rosacea Symptoms

Nearly 80% of all participants with facial erythema reported that it was difficult to control and unpredictable, but those with physician-diagnosed rosacea were almost twice as likely to have it under control through lifestyle changes and medication than those with undiagnosed rosacea (39% vs. 20%, p < 0.05). These people were significantly more likely to try a range of approaches to treat the symptoms of rosacea including taking prescription medicines (52% vs. 3%, p < 0.05), lifestyle changes (47% vs. 24%, p < 0.05), and using makeup to cover the erythema (55% vs. 35%, p < 0.05). In terms of motivation, 90% of those with physician-diagnosed rosacea self-reported that they were highly or somewhat motivated to deal with their facial redness versus 68% of those with undiagnosed rosacea (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The survey confirms the challenges of living with rosacea. Those suffering with dermatological conditions often experience high levels of self-consciousness, decreased quality of life and self-esteem and also face potentially negative first impressions and judgements of others. They must learn to cope with the challenges of living with an appearance that deviates from the norm, managing their own reactions to their condition and dealing with the reactions of those around them as well.

To complicate things further, rosacea can stay undiagnosed for a long time. Many people are unaware that their symptoms are caused by a medical condition and therefore are less likely to seek medical advice, remaining unaware of available therapies for many years. The survey highlighted that approximately only one in 10 people with self-reported rosacea had received a medical diagnosis. A delay in medical diagnosis results in the physical symptoms of the condition remaining unaddressed and the psychosocial impact unrecognized. However, importantly those who had been formally diagnosed were almost twice as likely to have their symptoms under control. This compounds the need for better education and access to professional advice to improve support and outcomes for those with facial erythema. These outcomes may also suggest that awareness of the condition is low and that facial erythema is an under-recognized symptom of rosacea. In addition, previously ineffective treatment options may have led to fewer doctor-determined diagnoses due to therapeutic inadequacy.

Previous studies show that those with rosacea are often affected by emotional disturbance and social stigma, and many report depression, anxiety, embarrassment and lowered self-esteem [9, 18]. Our research confirmed these findings that the facial erythema associated with rosacea can be a worrying and distressing condition. People with this condition were less happy with their skin appearance, suffered emotionally, socially, at work and in their relationships as a result of their condition compared to those without facial erythema.

The Emotix findings showed that people with facial erythema are judged more negatively on first impressions and thought of as less trustworthy, less reliable and less confident, purely on the appearance of their skin. Negative first impressions were also reflected in negative views on their work potential and social life. Previous authors have noted that rosacea can be a socially stigmatizing condition as people with facial erythema already have to cope with the common misconception that this is due to excessive alcohol consumption [6].

Existing psychological literature highlights the influence of visual information on our subsequent judgement of others. The brain uses first impressions about people to simplify decisions about our immediate safety. As we respond predominantly to visual stimuli it is easy to understand why the brain then attaches significant initial importance to visual cues from our environment. Engaging in quick evaluations of our visual environment enables us to respond quicker to threat and opportunity, which is vital for survival [26]. In this respect, we are particularly sensitive to detecting negative stimuli, or abnormal and unexpected features as these can signal risk/threat [27]. The images of facial redness of rosacea in this survey were most likely processed as unexpected or abnormal (and therefore a threat), triggering alarm and negative attitudes in participants.

Another key psychological factor is the ‘halo effect’ whereby a significant feature of a person (such as how they look) influences subsequent evaluations of their other characteristics (such as personality, intelligence, honesty, etc.). Originally used in educational psychology, this theory of cognitive bias has also found application in the impact of attractiveness on overall character traits [28]. In essence, it implies that ‘what is beautiful is good’—whereas facial erythema is perceived as not normal, not as attractive and negatively impacts other characteristics as seen in the results of the survey (where the photos indicating reddened faces were perceived as being less intelligent, etc.). However, the research also showed that once facial erythema is managed, often as a consequence of a professional diagnosis, those with rosacea feel better and more in control of their condition.

The survey has strengths, including the robust and reliable psychological assessments (which were able to take into account individual variance in response times affected by age and other factors) and the large numbers of participants from different countries and ethnicities with a wide spread of ages. The survey may have had limitations due to sourcing participants via online panels which necessitates internet access.

However, given that rosacea is a condition with widespread impact across a range of age groups, there is much to recommend the online approach. The quotas set in the design of the research allowed for careful management of those recruited to ensure adequate coverage for each country, and the online approach enabled the survey to reach a wide, diverse, representative audience. For the personal experiences section, participants had to fulfill screening criteria to exclude those with facial erythema that is unlikely to be associated with rosacea.

Conclusion

This survey shows that first impressions are a powerful driver of perception. People suffering with facial erythema associated with rosacea not only have to manage their own psychological barriers to cope with the disease but also deal with the prejudice and perceptions of others. Facial erythema tends to generate a negative first impression and has a negative impact on people both personally and professionally. The results highlight the need to treat those with facial erythema of rosacea from both a physiological and psychosocial perspective—treating not only the physical symptoms, but also the person experiencing the symptoms.

In addition, people with rosacea need to take steps to manage the triggers of their condition more effectively. The survey clearly shows that one of these steps is to receive a formal medical diagnosis of their condition as they are significantly more likely to have the condition under control. This highlights the importance of consulting a healthcare professional who can offer advice and appropriate treatment where necessary.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. The market research was performed by Bryter, an independent market research consultancy. The Emotix test was developed by Innovation Bubble. The research was commissioned by Galderma with an unrestricted medical education grant. Galderma funded sponsorship and article processing charges for this study including medical writing assistance and editing by Jeremy Bray, independent medical writer, with support from Ogilvy Healthworld.

Conflict of interest

Prof. Dr. Thomas Dirschka, Member of advisory boards: Almirall, Biofrontera, Galderma, Meda; Speaker: Almirall, Biofrontera, Galderma, Leo, Meda, Janssen Cilag.

Prof. Dr. Giuseppe Micali, Advisor: Pfizer, Abbvie, Eli Lilly, Bayer, Mundipharma, Galderma, Meda; Speaker: Galderma.

Dr. Linda Papadopoulos, Speaker: Galderma.

Dr. Jerry Tan, Advisor: Cipher, Galderma, Valeant; Consultant: Galderma; Speaker: Cipher, Galderma, Valeant; Investigator: Cipher, Dermira, Galderma.

Dr. Alison Layton, Advisor: Galderma, GSK-Stiefel, Meda; Speaker: Galderma, MEDA, GSK-Stiefel; Consultant: Galderma, L’Oréal; Investigator: Galderma, Leo, Valeant.

Dr. Simon Moore, Fees to implement Emotix research element of study (Innovation Bubble): Galderma.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Schaefer J, Rustenbach SJ, Zimmer L, Augustin M. Prevalence of skin diseases in a cohort of 48,665 employees in Germany. Dermatology. 2008;217:169–172. doi: 10.1159/000136656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg M, Liden S. An epidemiological study of rosacea. Acta Derm Venereol 1989;69(5): 419–23. [PubMed]

- 3.Abram K, Silm H, Oona M. Prevalence of rosacea in an Estonian working population using a standard classification. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:269–273. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culp B, Scheinfeld N. Rosacea: a review. Pharm Ther. 2009;34:38–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallen RS, Gooderham M. Rosacea: update on management and emerging therapies. Skin Therapy Lett 2012;17:1–4. [PubMed]

- 6.Powell FC. Rosacea. New Engl J Med 2005;352:793–803. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Huynh TT. Burden of disease: the psychological impact of rosacea on a patient’s quality of life. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6:348–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard grading system for rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:907–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blount BW, Pelletier AL. Rosacea: a common, yet commonly overlooked, condition. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:435–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker C, Papadopoulos L. Psychodermatology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dungey RK, Busselmeir TJ. Medical and psychosocial aspects of psoriasis. Health Soc Work. 1982;7:140–147. doi: 10.1093/hsw/7.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obermeyer A. Psychoses and disorders of the skin: psychocutaneous medicine. Illinois: Thomas Publishing; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porter JR, Beuf AH, Lerner A, Nordlund J. Response to cosmetic disfigurement: patients with vitiligo. Cutis. 1987;39:493–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papadopoulos L, Bor R. Psychological approaches to dermatology. Leicester: BPS; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB, Jr, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:400–407. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70112-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grandfield TA, Thompson AR, Turpin G. An attitudinal study of responses to a range of dermatological conditions using the implicit association test. J Health Psychol. 2005;10:821–829. doi: 10.1177/1359105305057316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson A. Psychosocial impact of skin conditions. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;8:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su D, Drummond PD. Blushing propensity and psychological distress in people with rosacea. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2012;19:488–495. doi: 10.1002/cpp.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Linden M, van Rappard D, Daams J, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with cutaneous rosacea: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:395–400. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JLK. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:1464–1480. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunel FF, Tietje BC, Greenwald AG. Is the implicit association test a valid and valuable measure of implicit consumer social cognition? J Consum Psychol. 2004;14:385–404. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp1404_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper LA, Roter D, Carson K, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:979–987. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown I. Nurses’ attitudes towards adult sufferers who are obese: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53:221–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan: London; 2011. ISBN 978-1-4299-6935-2.

- 26.Knoferlea P, Crocker MW, Scheepers C, Pickering MJ. The influence of the immediate visual context on incremental thematic role-assignment: evidence from eye-movements in depicted events. Cognition. 2005;95:95–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen JT, Smith NK, Cacioppo JT. Negative information weighs more heavily on the brain: the negativity bias in evaluative categorizations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:887–900. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nisbett RE, DeCamp Wilson T. The halo effect: evidence for unconscious alteration of judgements. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1977;35:250–256. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.35.4.250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.