Abstract

As American medicine continues to undergo significant transformation, the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) is emerging as an interprofessional primary care model designed to deliver the right care for patients, by the right professional, at the right time, in the right setting, for the right cost. A review of local, state, regional and national initiatives to train professionals in delivering care within the PCMH model reveals some successes, but substantial challenges. Workforce policy recommendations designed to improve PCMH effectiveness and efficiency include 1) adoption of an expanded definition of primary care, 2) fundamental redesign of health professions education, 3) payment reform, 4) responsiveness to local needs assessments, and 5) systems improvement to emphasize quality, population health, and health disparities.

Key words: Health policy; Workforce; Patient-centered care; Medical education—financing and administration; Medical education—interprofessional training, faculty development, undergraduate and graduate training

INTRODUCTION

American medicine is undergoing a transformation driven by the need to improve population health outcomes, enhance the patient care experience, and manage the cost of care, referred to as the "Triple Aim.1 Evidence continues to accumulate on the benefits of primary care, including a reduction in avoidable hospitalizations.2,3 Ideally, patients who are engaged in the patient-centered medical home (PCMH), especially those most vulnerable, will experience reduced health risks and improved outcomes. About half of the states in the U.S. are implementing the PCMH for their Medicaid populations in an effort to improve outcomes while controlling health care costs, as these populations are often at highest risk for poor health status,4 particularly in light of evidence that demonstrates a decrease in racial and ethnic disparities with implementation of the PCMH.5

With the passage of the Affordable Care Act that includes provisions to stimulate the development of new delivery models to promote access to primary care services and achieve the Triple Aim1, it is imperative to review factors that may enhance or impede wider adoption of the PCMH. Building on a successful conference in 20096, the Society of General Internal Medicine, in collaboration with the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine and the Academic Pediatric Association, hosted a second conference in 2013 to identify relevant research and policy agendas as well as to assess what, if any, significant impact the PCMH transformation may have from both a clinical and economic perspective.7

One of six groups, the PCMH Workforce Workgroup, was charged with identifying workforce-related research areas that could either facilitate or prevent wider PCMH adoption. These areas include the number and appropriate ratio of professionals required to maximize team effectiveness in delivering high-value care, required individual and collaborative training, and an evaluative schema for both practitioners and trainees. Research outcomes should inform policies and program initiatives at federal, state, and local levels, and address priorities relevant to academic institutions and accrediting, licensing, and funding bodies. This manuscript emerged from the deliberations of the Workforce Workgroup, with input from participants at the national conference. Professional groups represented included physicians, physician assistants, and nurses, all of whom endorse the principles of the PCMH and interprofessional education.8–12

Discussions revealed unanimous agreement that, beyond mastering the skills relevant to interprofessional practice, clinicians practicing in PCMHs must effectively engage patients, families, and communities, incorporate strategies that reduce health disparities, and integrate behavioral health team members. Health information technology must be employed both as a vehicle for communication among care team members and patients, and as a means to enhance quality assessment and improvement.

FACILITATORS AND EARLY ADOPTERS

The Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice (P4) initiative (2007–2012), sponsored by the American Board of Family Medicine, the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors, and TransforMED, was designed to drive graduate medical education reform among 14 residency programs in order to prepare family physicians for PCMH practice.13–15 The National Demonstration Project, launched by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2006 in an effort to assess the comprehensive PCMH model and findings related to transformation process requirements, reported in 2010 that this evolution was a complex process requiring motivated and engaged practice members. Over time, this process should continue to emphasize core attributes of collaborative care within primary care and attention to mental and public health.16

The Veterans Health Administration (VA) is the largest organization to have engaged in training clinicians in a PCMH model that includes undergraduate, graduate, and post-graduate levels of an array of health professionals.17,18 Through the PCMH-like model known as the Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT), the VA has hired and trained clinicians in the skills needed to deliver health care in more than 900 ambulatory practices through interprofessional teams as part of its New Models of Care transformation initiative introduced in 2011. The VA’s five Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education develop and test innovative approaches to educating health professionals, including medical students, resident physicians, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, behavioral health clinicians, and physician assistants, to provide care through implementation of the PCMH model.

VA-based trainees of all involved professions have reported deriving value from learning about professional development and roles of other primary care professions; they have also noted greater satisfaction with the increased patient continuity provided by these programs as well as with the curriculum incorporating performance improvement.19 The five Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education may offer important insights into system-level and local issues through expansion of interprofessional primary care education. Given the scale of the VA facilities serving as training locations, particularly in internal medicine, the impacts on trainees and faculty involved in the PACT educational intervention process are likely to increase as the VA expands the use of improved academic models across the system.

DRIVERS OF EDUCATIONAL CHANGE

Other national initiatives designed to train health care professionals in the PCMH include the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education (THCGME) and the Title VII Primary Care Training and Enhancement (PCTE) and Training in General Dentistry, Pediatric Dentistry, and Public Health Dentistry grant programs that support physician, physician assistant, dentist, and dental hygienist training in medical home models. The THCGME is based on evidence that residency training influences physician practice choices, with greater retention of physicians in primary care following completion of training in these settings.20 THCGME funds flow directly to the residency program, which is generally located in community health centers and rural health clinics that have traditionally delivered care with PCMH features.21 As of 2014, 60 THCGME residencies supporting more than 550 resident full-time equivalent positions in 24 states have been funded,22 an investment that will be sacrificed if Congress does not re-authorize funding beyond 2015.

In response to recommendations of the Advisory Committee for Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry, re-authorization of the Title VII grant program under the Affordable Care Act created new funding priorities to encourage applicants to propose educational innovations that equip students, residents, and faculty with the knowledge and skills necessary for interprofessional practice in a PCMH.23 These grants have helped to drive educational transformation and implementation of the PCMH in academic health centers (AHCs).24 The Interprofessional Education Collaborative has published competencies for team-based care,11 and the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC, www.pcpcc.org)Education and Training Task Force has endorsed specific PCMH competencies.25

In addition to the THCGME and Title VII Primary Care Training and Enhancement grant programs, in 2012 the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) funded a contract to provide faculty development focused on the promotion of PCMH curricular advancement and to support collaboration among the three primary care certification boards (internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics) in creating a pilot interdisciplinary faculty development program. The program focused on teamwork, change management, leadership, population management, clinical microsystems, and competency assessment skills.

Some have observed that there is a “perfect storm” brewing on the horizon in health care, as reform is implemented on multiple levels, highlighted by the Triple Aim. Increasingly, the PCPCC, with membership comprising payers, professional organizations, and health care systems, is demanding a delivery system—and by extension, an educational system—to support the PCMH model. The Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) is encouraging innovation in primary care and accelerated development and testing of new payment and service delivery models. Many CMMI efforts are focused on primary care, including the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative, the Federally Qualified Health Center Advanced Primary Care Practice Demonstration (FQHC APCP), the Independence at Home Demonstration project, and the Multi-payer Advanced Primary Care Initiative. Other initiatives relevant to primary care include programs targeting low-income adult and child (Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program [CHIP]) populations for testing of incentives for prevention of chronic disease and for enhanced prenatal care.

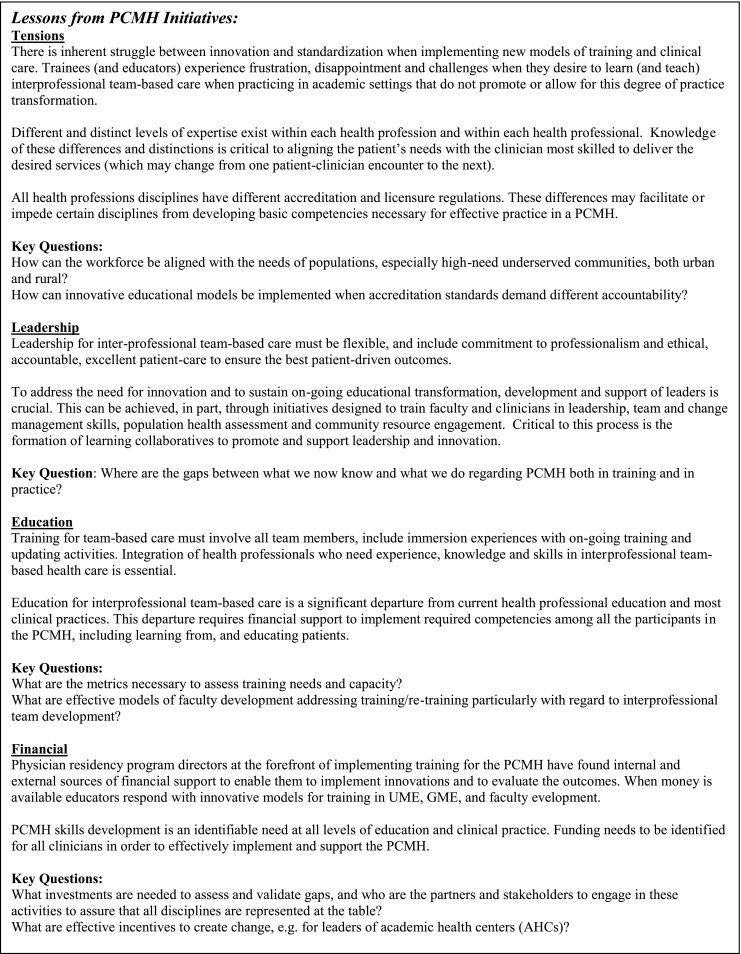

Lessons from early adopters, summarized in TextBox, point to the need for an aligned workforce through innovation, with standardization and acknowledgement of the various professional educational and accreditation requirements, population needs, knowledge gaps, and necessary metrics to assess training needs and capacity. Engagement of stakeholders and partners in identifying investments and incentives to facilitate continued workforce development is a key component that must be addressed.

BARRIERS TO PCMH ADOPTION

With few exceptions, AHCs—where training of most health professionals takes place—have historically not been early adopters of major systems innovations, particularly with respect to primary care. However, changes in payment incentives are leading AHCs to confront the shifting care delivery paradigms in order to achieve the Triple Aim. These efforts, stimulated by both federal and local incentives, include collaboration among organizations and institutions in focusing on adopting principles of the PCMH and team-based care in teaching practices that will affect learned skills of trainees. Emerging examples are found in multiple states, including California, Colorado, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Utah, where findings have been published. A major goal of these initiatives is to redesign both the work of primary care and the education of health professionals to encourage increasing numbers of clinicians to train in and practice primary care medicine.

However, even within these collaborative vanguards, simultaneous clinical supervision by faculty from multiple health professions, colleges, schools, or programs may be perceived as jeopardizing accreditation requirements and stretching limited resources. Many remain in an embryonic developmental stage. Barriers to educational reform include widely divergent professional accreditation and state licensing requirements, regulations that determine the scope of practice and clinical flexibility, and the practice patterns of licensed professionals. Those who are moving forward with implementation of PCMH training models using interprofessional teams are finding that while, leadership and team skills can be taught and assessed by any faculty member on these teams, discipline-specific skills, due to professional accreditation standards, generally require supervision by experienced, credentialed members of that discipline.

The Interprofessional Education Collaborative competencies for team-based care11 and the PCPCC-endorsed PCMH competencies25 help to define leadership and team skills. Endorsement of accreditation requirements or discipline-specific oversight to ensure the development of discipline-specific competencies, however, is well beyond the policy recommendations of these organizations, and thus there is a need to reconcile recommendations for training of health professionals with those for accreditation.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The PCMH Workforce Workgroup recommends policies in six areas and poses research-related questions (see TextBox); each area must include components that keep the focus on patients, families, and communities.

Conceptual

Implementation of primary care, defined by the Institute of Medicine in 1996 as “the provision of integrated accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community,”26 is a foundational element of health care infrastructure. The PCMH concept looks even beyond "family and community" to include population health, with attendant responsibilities such as quality assessment, reporting, and management. Physicians and other clinicians must function as members of teams to address patient and population needs; additional health professionals may include community health workers, behavioral health professionals, oral health professionals, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses, medical assistants, pharmacists, nutritionists, and others, in partnership with community organizations.

Education and Training

Fundamental redesign of health professional education will be necessary to prepare the interprofessional workforce with the essential competencies to work effectively in PCMH care settings. All health professionals will need to subordinate their parochial interests and, at the same time, achieve excellence in their discipline-specific knowledge and skills, as well as competence in skills essential for interprofessional team-based care. These newly defined competencies should be compatible with accreditation standards for each health discipline in order to facilitate transformation of training. Research on these competencies and their adoption in health professional education is sparse, but it is essential if the approach and principles are to be fully understood and implemented. Faculty development to ensure modeling of interprofessional care and education must be prioritized, along with development of appropriate competency assessments. Evaluations of both trainees and faculty should reinforce discipline-specific as well as team-based training with a focus on the patient, including measurable patient and population outcomes. Fundamental to all health professional education is knowledge and skills in cultural competence, health literacy, promotion of diversity, and reduction of health disparities.

Financing

Payment must be restructured to cover the costs of PCMH implementation, with expanded capacities and required infrastructure to enable distribution of responsibilities and services among team members. Experience to date suggests that interprofessional teamwork will involve specific personnel to ensure coordination and connectivity with communities. The goal of the payment system should be to incentivize and reward improved access to appropriate and timely care, reduce health disparities, and promote better health outcomes at lower overall cost.

Macro

Statewide, regional, and national initiatives should be developed to ensure a geographically distributed, diverse, values-driven interprofessional workforce equipped with leadership, communication, quality improvement, and population-oriented skills.

Local

Local population needs assessments should be conducted to determine how to optimize local adoption of effective services and ensure access. Needs assessments should seek to understand language and cultural barriers and community resources, including community health workers, knowledgeable patients, and family members, to maximize community engagement by combining primary care and public health approaches.

Systems Improvement

The workforce should be trained in a culture of continuous quality improvement and systems innovation. Systems must be designed to support the work of the primary care team through enhanced information technology and operations improvement. Practice-based data should capture appropriate health parameters and trainee, provider, and patient satisfaction, as well as expenditures and payments. Researchers should work alongside educators and clinicians as practice transformation occurs in order to evaluate population outcomes and costs. Population health should be a metric in assessing interprofessional education. The goals of training for the PCMH must be to improve access to high-quality, effective care that improves health, controls costs, and reduces disparities

Acknowledgments

This paper was developed from the 2013 Research Conference, hosted by the Society of General Internal Medicine, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine and the Academic Pediatric Association, and in partnership with the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality, the Veterans Health Administration, US Department of Veterans Affairs and the Commonwealth Fund.

Conflict of Interest

The authors each declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27:759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Physicians. How is a shortage of primary care physicians affecting the quality and cost of medical care? A comprehensive evidence review. 2008.

- 4.Takach M. About half of the states are implementing patient-centered medical homes for their medicaid populations. Health Aff. 2012;31:2432–2440. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beal AC, Doty MM, Hernandex SE, Shea KK, Davis K. Closing the Divide: How Medical Homes Promote Equity in Health Care: Results from The Commonwealth Fund 2006 Health Care Quality Survey. The Commonwealth Fund, June 2007.

- 6.Papers produced from the 2009 conference were published together in JGIM. JGIM 2010;25(6):581–634.

- 7.The conference was funded by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (#R13 HS21556). An executive committee was established, with representation from the three sponsoring organizations; an external advisory group included broad representation. The six working groups were as follows: workforce, payment reform, patient and family engagement, behavioral health, practice transformation, and health disparities. These topics were chosen after extensive discussion among the executive committee in consultation with the external advisory board.

- 8.AAFP, AAP, ACP, AOA. Joint Principles for the Medical Education of Physicians as Preparation for Practice in the PCMH, December 2010 http://www.acponline.org/running_practice/delivery_and_payment_models/pcmh/understanding/educ-joint-principles.pdf (accessed January 29, 2015)

- 9.Keahey D, Dickinson P, Hills K, Kaprielian V, Lohenry K, Marion G, et al. A STFM/PAEA Joint Position Statement Workgroup. Educating primary care teams for the future: family medicine and Physician assistant interprofessional education. communications. J Physician Assist Educ. 2012;23:33–41. doi: 10.1097/01367895-201223030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Organization of Nurse Practitioners Faculties. Nurse Practitioner Core Competencies. Amended 2012. https://nonpf.site-ym.com/?page=14 (accessed January 29, 2015)

- 11.The Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice May 2011. https://ipecollaborative.org/uploads/IP-Collaborative-Practice-Core-Competencies.pdf (accessed January 29, 2015)

- 12.Transforming Patient Care: Aligning Interprofessional Education with Clinical Practice Redesign, 2013 http://macyfoundation.org/docs/macy_pubs/TransformingPatientCare_ConferenceRec.pdf (accessed January 29, 2015)

- 13.Green LA, Pugno P, Fetter G, Jr, Jones SM. Preparing the personal physician for practice (P4): a national program testing innovations in family medicine residencies. J Amer Board Fam Med. 2007;20:329–331. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.04.070073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green LA, Jones SM, Fetter G, Pugno P. Preparing the personal physician for practice: changing family medicine residency training to enable new model practice. Acad Med. 2007;82:1220–1227. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318159d070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carney PA, Eiff PM, Green LA, Lindbloom E, Jones SE, Osborn J, et al. Preparing the personal physician for practice (P4): site-specific innovations, hypotheses, and measures at baseline. Fam Med. 2011;43:464–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stange KC, Stewart EE, Jaen CR. Summary of the national demonstration project and recommendations for the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:s80–s90. doi: 10.1370/afm.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein S. The Veterans Health Administration: Implementing patient-centered medical homes in the nation’s largest integrated delivery system. Commonwealth Fund pub. 1537. Sept. 2011. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/case-studies/2011/sep/va-medical-homes (accessed January 29, 2015)

- 18.Rosland A, Nelson K, Sun H, Dolan ED, Maynard C, Bryson C, et al. The patient-centered medical home in Veterans Health Administration. Amer J Managed Care. 2013;19(7):e263–e272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilman SC, Chokshi DA, Rugen KW, Bowen JL, Cox M. Connecting the dots: health professions education and delivery redesign. Acad Med. 2014;89:1113–1116. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds PP. The teaching community health center: an idea whose time has come. Acad Med. 2012;87:1648–1650. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318272cbc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen C, Chen F, Mullan F. Teaching health centers: a new paradigm in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87:1752–1756. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182720f4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teaching Health Center GME 2014 Grant Awards http://www.hrsa.gov/about/news/2014tables/teachinghealthcenters/ (accessed January 29, 2015)

- 23.Advisory Committee on Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry. The Redesign of Primary Care with Implications for Training. Eighth Annual Report 2010.

- 24.Klink KA, Joice SE, McDevitt SK. Impact of the affordable care act on grant-supported primary care faculty development. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):419–423. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00329.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative. http://www.pcpcc.org/content/primary-care-workforce-competencies (accessed September 4, 2014)

- 26.Institute of Medicine. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. 1996 http://www.nap.edu/nap/online (accessed January 29, 2015)