For decades, cardiovascular risk attributed to lipids beyond low-density lipoprotein (LDL) has focused appropriately on high-density lipoprotein (HDL). Indubitable observational data show a consistent inverse relationship between baseline HDL-C concentrations and cardiovascular risk. Yet, fidelity as a prospective risk marker does not guaranty that an analyte either lies in a causal pathway for disease, or that its therapeutic manipulation will yield clinical benefits. Indeed, multiple strategies to raise HDL levels therapeutically have thus far failed to forestall events in clinical trials [e.g. currently available fibrates, niacin, and the investigated cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors]. We await eagerly with an open mind, however, results from the ongoing outcome trials with two additional CETP inhibitors. We also recognize that steady-state concentrations of HDL-C in plasma likely do not reflect the flux of HDL particles, their potential for mediating reverse cholesterol transport, and other putative functions of HDL subclasses. For example, a large body of in vitro and experimental animal studies indicates that HDL particles may have many beneficial actions beyond reverse cholesterol transport. These putative properties of HDL particles include anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, attributes not assessed by the simple laboratory measurement of HDL-C. These functional facets of HDL may provide novel targets for therapeutic manipulation in a more subtle fashion in the future. Yet, concordant with the data from clinical intervention trials showing lack of benefit (or even harm) with current approaches to pharmacological boosting of HDL-C, recent genetic studies have also cast doubt on HDL-C as a causal risk factor.1

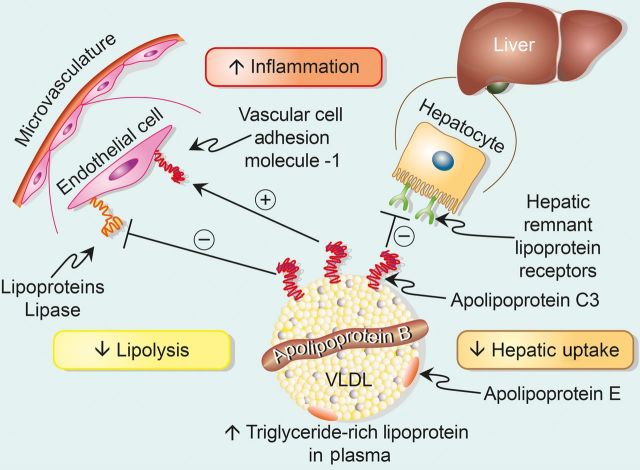

While HDL-C has stood in the spotlight, centre stage, triglycerides have tarried in the wings as a causal cardiovascular risk factor. Adjustment for HDL-C and for other potential confounders tends to attenuate or nullify the association between triglyceride concentration and prospective cardiovascular risk.2,3 HDL-C and triglyceride concentration in plasma tend to vary inversely, such that high levels of triglycerides associate with low levels of HDL, until recently the presumed causal partner in the pair (Figure 1). Curiously, we generally measure fasting triglycerides, although many spend most of their time in post-prandial in the state, bathing our arteries with triglyceride-rich lipoproteins.4 Yet, current data show that either fasting or fed triglyceride concentrations associate with cardiovascular events.5,6

Figure 1.

The high-density lipoprotein/triglyceride seesaw. High-density lipoprotein and triglycerides tend to vary inversely. Traditional thought has focused on the benefits of raising high-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein as a protective factor for atherosclerosis. Triglycerides have received less attention as a causal risk factor as adjustment for high-density lipoprotein attenuates its association with risk. The new clinical and genetic data described in this commentary indicate that triglycerides and specifically the apolipoprotein constituent of many triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, apolipoprotein C3, may actually lie in the causal pathway for atherosclerosis. Thus, contrary to common belief, the current data suggest that we should focus more on triglyceride-rich lipoproteins as a target for cardiovascular risk reduction.

Fasting or fed, perhaps adjusting triglycerides for HDL-C, instead of the other way around, has misled us. Have we have collectively chosen a seat on the wrong side of the HDL/triglyceride seesaw? (Figure 1). Recent genetic studies have occasioned a re-examination of triglycerides as a causal cardiovascular risk factor. Contemporary genetic analyses indicate that higher concentrations of triglyceride and remnant lipoproteins contribute directly to the pathogenesis of ischaemic heart disease.7,8 The cholesterol content of remnant particles rather than triglycerides themselves likely comprise the causal moiety contained in this lipoprotein class.9 The actual gene or genes responsible for this association have remained conjectural. One protein associated with triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, apolipoprotein C3 (APOC3), associates with cardiovascular risk. The study of the Amish population in Pennsylvania suggested that carriers of an inactive APOC3 gene have lower triglycerides and lower coronary artery calcium scores than unaffected individuals.10

Two independent large studies recently published in New England Journal of Medicine provide strong evidence for the causal role of APOC3 and triglycerides in atherosclerotic vascular disease.11,12 Exxon sequencing of large cohorts in the USA tracked four loss-of-function variants in APOC3. The individuals with such variants had lower triglyceride concentrations, and correspondingly lower risk of coronary heart disease in validation studies. A parallel study performed in Danish populations that screened for certain known mutations in APOC3 yielded a similar result, and showed that those with lifelong low levels of triglycerides due to these gene variants have fewer stroke as well as ischaemic heart disease events.

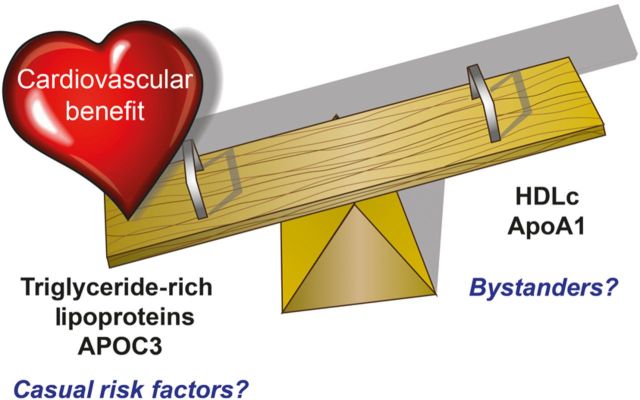

These results make sense mechanistically (Figure 2), as APOC3 can inhibit lipoprotein lipase (LPL), limiting the clearance of triglycerides from plasma (in part by interfering with LPL activation by APOCII) and impeding the clearance of atherogenic lipoproteins by the liver.13 APOC3 may also have direct proinflammatory effects, and/or impair some of the putative beneficial properties attributed to HDL particles.13,14 Indeed, HDL particles that bear APOC3 associate with increased rather than decreased risk for coronary heart disease.15 APOC3 can augment apoptosis of endothelial cells as well.16 The risk contribution determined from genetic analysis of APOC3 exceeds that estimated by observational studies, supporting the effects of lifelong alteration in this exposure and/or adverse effects of these apolipoprotein on vascular pathobiology not captured in the lipid values per se.8 The finding that remnant cholesterol, but not LDL cholesterol, associates with inflammation, as measured by C-reactive protein, also provides mechanistic support for triglyceride-rich lipoproteins as a trigger for atherothrombotic events.17

Figure 2.

Apolipoprotein C3 regulates triglyceride-rich lipoprotein concentrations and can promote inflammation. The figure depicts very low-density lipoprotein as a prototypical triglyceride-rich lipoprotein. The single equatorial apolipoprotein B moiety encircles the particle. Apolipoprotein constituents associated with a sub-population of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins include apolipoprotein E (a key ligand for the low-density lipoprotein receptor) and apolipoprotein C3, implicated in atherogenesis by a variety of observational, in vitro, and genetic studies as discussed. In particular, apolipoprotein C3 can inhibit lipoprotein lipase preventing the catabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and raise their steady-state concentration due to a decrease in lipolysis. Apolipoprotein C3 can also inhibit the uptake of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein particles by remnant lipoprotein receptors, for example expressed on the surface of the hepatocyte as depicted. This inhibition of peripheral uptake of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins will conspire with the reduced lipolysis to increase further the concentration of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in the plasma. In addition to these alterations in the metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, apolipoprotein C3 may have direct proinflammatory effects, for example the induction of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, an endothelial-leucocyte adhesion molecule implicated in recruitment of monocytes, the precursor of foam cells in the atherosclerotic plaque and contributors to ongoing inflammation implicated in plaque evolution and complication.

As individuals with the APOC3 loss-of-function mutations also had higher concentrations of plasma HDL, one cannot formally exclude that higher HDL contributed to the risk reduction observed in these two studies. Indeed, case reports of combined deficiency of apoliprototein AI (the major protein constituent of HDL particles) and APOC3 associated with premature atherosclerosis. Yet the preponderance of the current genetic evidence sways the seesaw surely to the triglyceride side.

These results have important implications for clinical practice. They should renew interest in triglycerides and APOC3 as therapeutic targets for cardiovascular risk reduction. These recent genetic studies show that a lifetime of lower exposure to APOC3 reduced cardiovascular risk. Whether therapeutic intervention on these targets might mitigate cardiovascular risk of patients with well-controlled LDL levels over a shorter time span will require rigorous clinical evaluation. These new, exciting, and concordant genetic studies in humans should stimulate this quest.

In the meantime, what should clinicians do to manage patients who present with hypertriglyceridemia?18 These new data regarding a causal role for triglycerides in increasing cardiovascular risk should prompt us today to redouble our efforts to reduce hypertriglyceridemia in our patients using non-pharmacological approaches. We should examine the medication list for agents that might raise triglyceride levels such as estrogens and retinoic acid products.18 We should consider whether alcohol consumption or thyroid disease contributes to dyslipidemia in individual patients. We should strive to achieve optimum control in diabetic patients. We can discourage excessive carbohydrate consumption in those with hypertriglyceridemia.

The tension twixt triglycerides and HDL told above provides one example of how modern genetic tools have begun to yield practical dividends for preventive and cardiovascular specialists. In another recent instance of note, the identification of proprotein convertase subtilysin kexin 9 (PCSK9) as a cause of autosomal-dominant hypercholesterolemia has led to the development of novel therapeutic agents in warp speed, and spawned a series of global trials currently evaluating their effectiveness in improving cardiovascular outcomes. In the case of triglycerides in general, and specifically APOC3, studies currently underway with omega-3 fatty acids and development of anti-sense oligonucleotides or siRNA that target APOC3 may yield practical applications of the inversion in emphasis described here. We stand on the threshold of an exciting era in cardiovascular disease when genetic insights can guide our practice, challenge our preconceptions, point to new mechanisms, and promise ultimately to usher in novel therapies to help our patients at risk.

Funding

P.L. is supported by funds from the National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute (R01 HL080472) and Leducq TransAtlantic Network of Excellence on Atherothrombosis Research.

Conflict of interest: P.L. is an unpaid consultant to AstraZeneca, Esperion Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, and Kowa Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M, Frikke-Schmidt R, Barbalic M, Jensen MK, Hindy G, Holm H, Ding EL, Johnson T, Schunkert H, Samani NJ, Clarke R, Hopewell JC, Thompson JF, Li M, Thorleifsson G, Newton-Cheh C, Musunuru K, Pirruccello JP, Saleheen D, Chen L, Stewart A, Schillert A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Thorgeirsson G, Anand S, Engert JC, Morgan T, Spertus J, Stoll M, Berger K, Martinelli N, Girelli D, McKeown PP, Patterson CC, Epstein SE, Devaney J, Burnett MS, Mooser V, Ripatti S, Surakka I, Nieminen MS, Sinisalo J, Lokki ML, Perola M, Havulinna A, de Faire U, Gigante B, Ingelsson E, Zeller T, Wild P, de Bakker PI, Klungel OH, Maitland-van der Zee AH, Peters BJ, de Boer A, Grobbee DE, Kamphuisen PW, Deneer VH, Elbers CC, Onland-Moret NC, Hofker MH, Wijmenga C, Verschuren WM, Boer JM, van der Schouw YT, Rasheed A, Frossard P, Demissie S, Willer C, Do R, Ordovas JM, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M, Mohlke KL, Daly MJ, Guiducci C, Burtt NP, Surti A, Gonzalez E, Purcell S, Gabriel S, Marrugat J, Peden J, Erdmann J, Diemert P, Willenborg C, Konig IR, Fischer M, Hengstenberg C, Ziegler A, Buysschaert I, Lambrechts D, Van de Werf F, Fox KA, El Mokhtari NE, Rubin D, Schrezenmeir J, Schreiber S, Schafer A, Danesh J, Blankenberg S, Roberts R, McPherson R, Watkins H, Hall AS, Overvad K, Rimm E, Boerwinkle E, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Cupples LA, Reilly MP, Melander O, Mannucci PM, Ardissino D, Siscovick D, Elosua R, Stefansson K, O'Donnell CJ, Salomaa V, Rader DJ, Peltonen L, Schwartz SM, Altshuler D, Kathiresan S. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a Mendelian randomisation study. Lancet 2012;380:572–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarwar N, Danesh J, Eiriksdottir G, Sigurdsson G, Wareham N, Bingham S, Boekholdt SM, Khaw KT, Gudnason V. Triglycerides and the risk of coronary heart disease: 10,158 incident cases among 262,525 participants in 29 Western prospective studies. Circulation 2007;115:450–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarwar N, Sandhu MS, Ricketts SL, Butterworth AS, Di Angelantonio E, Boekholdt SM, Ouwehand W, Watkins H, Samani NJ, Saleheen D, Lawlor D, Reilly MP, Hingorani AD, Talmud PJ, Danesh J. Triglyceride-mediated pathways and coronary disease: collaborative analysis of 101 studies. Lancet 2010;375:1634–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zilversmit DB. Atherogenic nature of triglycerides, postprandial lipidemia, and triglyceride-rich remnant lipoproteins. Clin Chem 1995;41:153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bansal S, Buring JE, Rifai N, Mora S, Sacks FM, Ridker PM. Fasting compared with nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in women. JAMA 2007;298:309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Schnohr P, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA 2007;298:299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, West AS, Grande P, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Genetically elevated non-fasting triglycerides and calculated remnant cholesterol as causal risk factors for myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1826–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varbo A, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG. Remnant cholesterol as a causal risk factor for ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordestgaard BG, Varbo A. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease. Lancet 2014;384:626–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollin TI, Damcott CM, Shen H, Ott SH, Shelton J, Horenstein RB, Post W, McLenithan JC, Bielak LF, Peyser PA, Mitchell BD, Miller M, O'Connell JR, Shuldiner AR. A null mutation in human APOC3 confers a favorable plasma lipid profile and apparent cardioprotection. Science 2008;322:1702–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3 and risk of ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med 2014;371:22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The TG and HDL Working Group of the Exome Sequencing Project NHL and Blood I. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3, triglycerides, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2014;371:32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sacks FM, Zheng C, Cohn JS. Complexities of plasma apolipoprotein C-III metabolism. J Lipid Res 2011;52:1067–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng C, Azcutia V, Aikawa E, Figueiredo JL, Croce K, Sonoki H, Sacks FM, Luscinskas FW, Aikawa M. Statins suppress apolipoprotein CIII-induced vascular endothelial cell activation and monocyte adhesion. Eur Heart J 2013;34:615–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen MK, Rimm EB, Furtado JD, Sacks FM. Apolipoprotein C-III as a potential modulator of the association between HDL-cholesterol and incident coronary heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2012;1:jah3-e000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riwanto M, Rohrer L, Roschitzki B, Besler C, Mocharla P, Mueller M, Perisa D, Heinrich K, Altwegg L, von Eckardstein A, Luscher TF, Landmesser U. Altered activation of endothelial anti- and proapoptotic pathways by high-density lipoprotein from patients with coronary artery disease: role of high-density lipoprotein-proteome remodeling. Circulation 2013;127:891–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varbo A, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated remnant cholesterol causes both low-grade inflammation and ischemic heart disease, whereas elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol causes ischemic heart disease without inflammation. Circulation 2013;128:1298–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, Nordestgaard BG, Kuivenhoven JA, Averna M, Borén J, Bruckert E, Catapano AL, Descamps OS, Hovingh GK, Humphries SE, Kovanen PT, Masana L, Pajukanta P, Parhofer KG, Raal FJ, Ray KK, Santos RD, Stalenhoef AFH, Stroes E, Taskinen M-R, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Watts GF, Wiklund O. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2013;2:655–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]