Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the oncological efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) as first-line molecular-targeted therapy for Japanese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) in a routine clinical setting. This study included a total of 271 consecutive Japanese patients with TKI-naive mRCC, including 172 patients who received sorafenib and 99 who received sunitinib for ≥2 months as a first-line molecular-targeted agent. The prognostic outcomes of these patients were retrospectively assessed. During the observation period (median, 19 months), 126 patients (46.5%) succumbed to the disease and the median overall survival (OS) for the entire cohort was 33.1 months. The univariate analysis identified the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) classification, C-reactive protein (CRP) level, lymph node metastasis, bone metastasis, liver metastasis, histological subtype and sarcomatoid characteristics as significant predictors of OS. Of these factors, only the MSKCC classification, CRP level and liver metastasis were found to be independently associated with OS in the multivariate analysis. Furthermore, there were significant differences in OS according to the positivity for these 3 independent risk factors (i.e., negative for all factors vs. positive for a single factor vs. positive for 2 or 3 factors). These findings suggest that the introduction of TKIs as first-line molecular-targeted agents resulted in favorable cancer control outcomes in Japanese mRCC patients and that the prognosis of these patients may be stratified by 3 potential parameters, including the MSKCC classification, CRP level and liver metastasis.

Keywords: renal cell carcinoma, tyrosine kinase inhibitor, sorafenib, sunitinib, overall survival

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is characterized by a highly resistant phenotype to conventional non-surgical therapeutic modalities; therefore, immunotherapy with cytokines was the previous mainstay of treatment for metastatic RCC (mRCC), although only limited disease control was achieved with this treatment, with a median overall survival (OS) of ~1 year (1). However, novel molecular-targeted agents have been developed based on intensive research of the molecular mechanisms underlying the progression of RCC and the recent introduction of these agents has revolutionized the therapeutic strategy against mRCC (2).

Of the several types of molecular-targeted agents, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which mainly ACT BY inactivating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-related pathways, are considered to exhibit powerful antitumor activities against mRCC, based on the outcomes of pivotal randomized clinical trials (3–6). Therefore, TKIs currently play a central role in the treatment of patients with mRCC, particularly as first-line standard of care (7). Furthermore, the excellent antitumor activities of TKIs against mRCC were confirmed by various studies evaluating these agents in routine clinical settings (8–12). For example, Gore et al (8) reported the efficacy and safety profile of sunitinib in a global expanded-access trial for patients with mRCC, with results similar to those of phase III clinical trials. Considering these findings, it may be crucial to assess the detailed prognostic effect of TKIs introduced as first-line agents against mRCC in order to provide optimal patient counseling, risk-directed therapy and clinical trial design in the era of molecular-targeted therapy.

Three types of TKIs are applicable for patients with TKI-naive RCC in Japan (13); sorafenib and sunitinib were approved in 2008 and have been widely recognized as efficacious systemic agents for the treatment of mRCC, while pazopanib became available in 2014. However, there have been no studies including a comparatively large number of Japanese patients treated with TKIs as first-line therapy for mRCC. Considering these findings, we retrospectively reviewed our experience with the use of TKIs as first-line molecular-targeted agents in a total of 271 consecutive Japanese mRCC patients in a routine clinical setting and analyzed the oncological outcomes in order to identify prognostic factors in this cohort of patients.

Patients and methods

Patients

This study included a total of 271 consecutive Japanese patients with TKI-naive mRCC who were treated with either sorafenib or sunitinib as first-line molecular-targeted therapy for ≥2 months between April, 2008 and September, 2013 in a routine clinical setting at our institutions. Of these 271 patients, 26 were not treated by radical nephrectomy, but underwent needle biopsies of either the primary or metastatic tumor to determine the histological subtype; therefore, all the included patients were pathologically diagnosed with primary RCC. Prior to participation in this study, informed consent was obtained from each patient and the study design was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of our institutions.

TKI administration

In this series, all the patients initially received either 400 mg of sorafenib twice daily with a continuous dosing schedule, or 50 mg of sunitinib once daily in repeated 6-week cycles (4 weeks on, followed by 2 weeks off). Treatment with TKIs was continued until disease progression or the development of intolerable adverse events (AEs). As a rule, TKI dose modification was conducted in cases with treatment-related GRADE ≥3 AEs as follows: the dose of sorafenib was reduced from 800 to 400 mg once daily, followed by additional dose reduction to a single 400 mg dose every other day, while the dose reduction of sunitinib was from 50 to 37.5 mg once daily and then to 25 mg once daily. Informed consent was obtained prior to treatment modification for all the patients.

Evaluation

As baseline evaluations, the clinicopathological examination, performance status (PS) and risk classification were assessed based on the union for international cancer control TNM classification system, Karnofsky PS scale and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) risk classification (14), respectively. Prior to the initiation of TKI treatment, radiological evaluation of all the patients was conducted by computed tomography (CT) SCANs of the brain, chest and abdomen and radionuclide bone scan. As a rule, tumor measurements were performed by CT prior TO and every 12 weeks following TKI introduction. The response to treatment and the severity of the AEs were analyzed by the treating physician based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.0 and the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed using Statview 5.0 software (Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA) and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. The OS rates were calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method and the differences were determined by the log-rank test. The prognostic significance of certain factors was assessed using the Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Results

Patient characteristics

The detailed baseline characteristics of the 271 patients included in this study are summarized in Table I. Of these 271 patients, 172 (63.5%) and 99 (36.5%) were treated with sorafenib and sunitinib, respectively. The tumor response to TKIs in the 271 patients was as follows: 3 (1.1%), 47 (17.3%) and 182 (67.2%) patients exhibited a complete response (CR), partial response (PR) and stable disease, respectively, for ≥6 weeks; however, the remaining 39 patients (14.4%) exhibited progressive disease. Therefore, the objective response and clinical benefit rates on TKI treatment were 18.4 and 85.6%, respectively (data not shown).

Table I.

Patient characteristics according to overall survival.

| Overall survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total (n=271) | Deceased (n=126) | Alive (n=145) | P-value |

| Age, years (%) | 0.40 | |||

| ≤65 | 126(46.5) | 62(49.2) | 64(44.1) | |

| >65 | 145(53.5) | 64(50.8) | 81(55.9) | |

| Gender(%) | 0.22 | |||

| Male | 215(79.3) | 104(82.5) | 111(76.6) | |

| Female | 56(20.7) | 22(17.5) | 34(23.4) | |

| Prior immunotherapy(%) | 0.79 | |||

| Yes | 172(63.5) | 81(64.3) | 91(62.8) | |

| No | 99(36.5) | 45(35.7) | 54(37.2) | |

| MSKCC classification(%) | <0.001 | |||

| Favorable or intermediate | 227(83.8) | 92(83.0) | 135(93.1) | |

| Poor | 44(16.2) | 34(27.0) | 10(6.9) | |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dl(%) | <0.001 | |||

| ≥1.0 | 187(69.0) | 61(48.4) | 126(86.9) | |

| <1.0 | 84(31.0) | 65(51.6) | 19(13.1) | |

| Metastatic organ(%) | ||||

| Lung | 177(65.3) | 83(65.9) | 94(64.8) | 0.85 |

| Lymph node | 69(25.5) | 43(34.1) | 26(17.9) | 0.0023 |

| Bone | 55(20.3) | 32(25.4) | 23(15.9) | 0.052 |

| Liver | 31(11.4) | 25(19.8) | 6(4.1) | <0.001 |

| Brain | 21(7.7) | 13(10.3) | 8(5.5) | 0.14 |

| Histological subtype(%) | 0.17 | |||

| Clear cell carcinoma | 231(85.2) | 103(81.7) | 128(88.3) | |

| Other | 40(14.8) | 23(18.3) | 17(11.7) | |

| Sarcomatoid characteristics(%) | 0.58 | |||

| Yes | 32(11.8) | 24(19.0) | 8(5.5) | |

| No | 239(88.2) | 102(81.0) | 137(94.5) | |

MSKCC, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

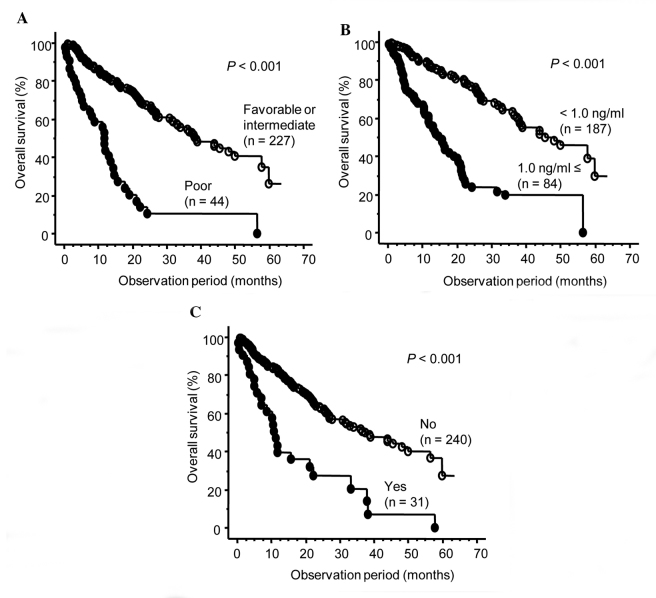

Overall survival

During the observation period of this study (median, 19 months; range, 2–64 months), 126 patients (46.5%) succumbed to the disease. As shown in Fig. 1, the median OS in this series was 33.1 months and the 1- and 3-year OS rates were 77.3 and 48.8%, respectively. Table I shows the distribution of several parameters according to the OS. The clinicopathological characteristics that were significantly correlated with poor OS included a poor-prognosis group based on MSKCC classification, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, presence of lymph node metastasis and presence of liver metastasis.

Figure 1.

Overall survival of the 271 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received tyrosine kinase inhibitors as first-line molecular-targeted therapy.

Uni- and multivariate analyses of the association between various factors and overall survival

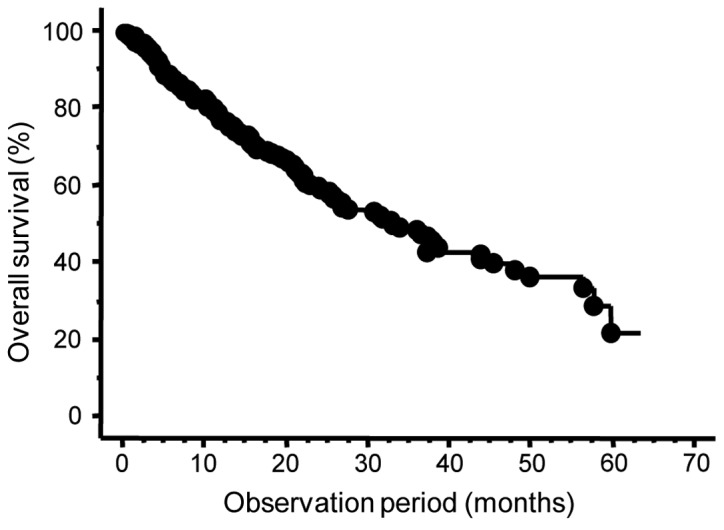

The effect of several clinicopathological factors on the OS in these 271 patients was analyzed by uni- and multivariate analyses using the Cox proportional hazards regression model (Table II). the univariate analysis identified prior nephrectomy, MSKCC classification, CRP level, lymph node, bone and liver metastases, histological subtype and sarcomatoid characteristics as significant predictors of OS. Furthermore, of these 7 factors, only MSKCC classification, CRP level and liver metastasis were found to be independently associated with OS in the multivariate analysis. The OS curves according to these independent OS predictors are presented in Fig. 2. There were significant differences in OS with respect to all 3 factors.

Table II.

Uni- and multivariate analyses of association between various factors and overall survival in 271 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who were treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | Hazard ratio | P-value | Hazard ratio | P-value |

| Age, years (<60 vs. ≥60) | 1.02 | 0.92 | – | – |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 1.47 | 0.15 | – | – |

| Prior immunotherapy (yes vs. no) | 1.37 | 0.10 | – | – |

| MSKCC classification (poor vs. favorable or intermediate) | 4.31 | <0.001 | 1.73 | 0.038 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dl (≥1.0 vs. <1.0) | 3.69 | <0.001 | 2.80 | <0.001 |

| Lung metastasis (yes vs. no) | 1.16 | 0.45 | – | – |

| Lymph node metastasis (yes vs. no) | 1.59 | 0.014 | 1.12 | 0.57 |

| Bone metastasis (yes vs. no) | 1.67 | 0.026 | 1.14 | 0.51 |

| Liver metastasis (yes vs. no) | 3.08 | <0.001 | 2.37 | 0.0030 |

| Brain metastasis (yes vs. no) | 1.09 | 0.78 | – | – |

| Histological subtype (clear cell carcinoma vs. others) | 1.66 | 0.030 | 1.04 | 0.88 |

| Sarcomatoid characteristics (yes vs. no) | 2.45 | <0.001 | 1.55 | 0.082 |

MSKCC, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Figure 2.

Overall survival of the 271 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received tyrosine kinase inhibitors as first-line molecular-targeted therapy according to (A) the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center classification, (B) C-reactive protein level and (C) liver metastasis.

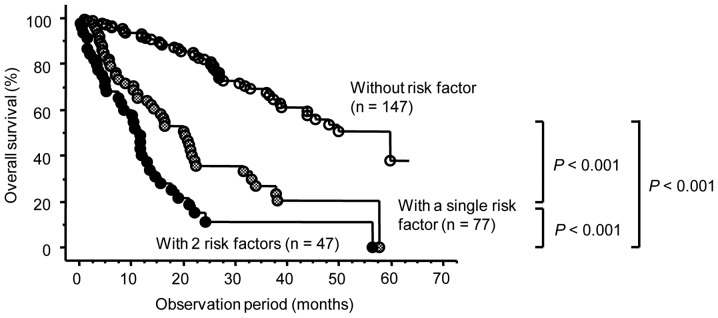

To more accurately predict OS in this patient cohort, we classified the 271 patients into 3 groups based on positivity for the 3 independent risk factors for OS identified by the multivariate analysis. Overall, 46 of the 147 patients (31.3%) who were negative for all 3 risk factors, 45 of the 77 patients (58.3%) who were positive for a single risk factor and 35 of the 47 patients (74.5%) who were positive for 2 or 3 risk factors succumbed to the disease. As shown in Fig. 3, there were significant differences in OS among these 3 groups.

Figure 3.

Overall survival (OS) of the 271 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received tyrosine kinase inhibitors as first-line molecular-targeted therapy according to the number of independent risk factors for OS, including the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center classification, C-reactive protein level and liver metastasis.

Discussion

As a result of the pivotal randomized phase III clinical trials, TKIs are currently considered as a new reference standard of care for the first-line treatment of mRCC, excluding patients classified into the poor-prognosis group. For example, sorafenib achieved significantly longer progression-free survival (PFS) compared TO placebo in patients with TKI-naive mRCC following failure of one systemic therapy, the majority of whom had received cytokine-based treatment (3). Similarly, sunitinib exhibited efficacy superior to that of interferon-α (IFN-α) as first-line therapy for mRCC, with a median PFS of 11 vs. 5 months, respectively (4). Furthermore, the therapeutic efficacy of TKIs observed in clinical trials was subsequently confirmed in several studies targeting mRCC patients treated with TKIs in routine clinical practice (8–12). To date, however, there have not been any data from a large number of Japanese patients with mRCC treated with TKIs as first-line molecular-targeted therapy; therefore, we retrospectively investigated the oncological outcomes in a total of 271 patients who received either sorafenib or sunitinib for TKI-naive mRCC.

In this series, a total of 50 patients were classified as exhibiting CR or PR, resulting in an objective response rate of 18.4%. This outcome may be explained as follows: This study included a larger proportion of patients receiving sorafenib, which is characterized by a significantly lower response rate compared to that of sunitinib; in addition, it is generally difficult to achieve a response rate to TKIs in a routine clinical setting superior to that in a clinical trial, due to the presence of a certain proportion of patients with unfavorable characteristics in the general MRCC patient population, who do not meet the inclusion criteria for clinical trials (15). In fact, the response rates to sorafenib and sunitinib were reported to be 9.8 and 30.7%, respectively, in phase III clinical trials (3,4), while expanded-access trials reported response rates to sorafenib and sunitinib of 4.0 and 17.4%, respectively (8,10). In addition, the median OS of this series was 33.1 months, which is also very favorable, even when compared to the OS reported in a clinical trial (28.4 months) as well as an expanded-access study (18.4 months) in patients receiving sunitinib (4,10). Collectively, these findings strongly suggest the usefulness of first-line TKI therapy in Japanese patients without prior treatment with a molecular-targeted agent.

It is of interest to identify factors associated with the prognosis of Japanese mRCC patients treated with TKIs as the first-line molecular-targeted therapy in an actual clinical setting. In this series, of the 7 significant predictors of OS identified by univariate analysis, the MSKCC classification, CRP level and liver metastasis were found to be independently correlated with OS. The prognostic significance of these parameters has already been reported in several previous studies (11,13–17). The common findings regarding prognostic indicators across various studies suggest the significant effect of the underlying biology of mRCC on disease control, even in the era of molecular-targeted therapy.

Another point of interest is to develop a system that allows a more precise assessment of the prognostic risk in individual patients with mRCC receiving TKIs as first-line molecular-targeted therapy, since such a tool would be useful for counseling patients and planning therapeutic options and follow-up schedule. To date, the most widely used system is the MSKCC classification model that may facilitate prognostic individualization in mRCC patients who have received systemic therapy (14); however, despite being validated in the era of molecular-targeted therapy (18), this model was developed based on data from patients treated with IFN-α in a clinical trial. To overcome such possible limitations of the MSKCC classification, Heng et al (11) presented a novel model to assess the prognosis of TKI-naive mRCC patients treated with VEGF-targeted agents in routine clinical practice. In this series, we evaluated the ability to predict the prognosis of mRCC patients following TKI introduction by combining 3 independent risk factors identified in this study (i.e., MSKCC classification, CRP level and liver metastasis) and demonstrated that it is possible to stratify OS according to the positivity for these factors. However, to draw a definitive conclusion regarding the significance of our model, it requires prospective validation based on data from a larger patient sample.

Although it was not a major objective of this study to compare the treatment efficacy between the sorafenib and sunitinib groups, this assessment may help guide decisions on the therapeutic strategy for patients with TKI-naive mRCC. It is currently hypothesized that the majority of Japanese mRCC patients, who are classified into a favorable or an intermediate risk group, are initially treated with sunitinib. Until recently, however, sorafenib and sunitinib tended to be separately administered to mRCC patients with comparatively favorable and unfavorable characteristics, respectively (19), due to several background factors in Japan as follows: Even after the introduction of molecular-targeted agents, immunotherapy was still likely to be administered to mRCC patients, particularly to those classified into the favorable risk group and due to the delayed approval of temsirolimus, a suitable agent for patients classified into the poor-prognosis group (20), this category of patients was preferably treated with sunitinib. Although this trend appeared to be marked in this study as well, there was no significant difference in the OS between the sorafenib and sunitinib groups and the OS in the sunitinib group with unfavorable characteristics, such as elevated CRP level, appeared to be superior to that in the sorafenib group (data not shown). Considering these findings, it is highly recommended to administer sunitinib as a first-line systemic agent to the majority of mRCC patients, apart from those in the poor-prognosis group.

There were several limitations to this study. First, although this series may include the largest number of Japanese mRCC patients who received TKIs as first-line molecular-targeted agents, this was a retrospective study conducted in a routine clinical setting; therefore, the findings of this study require confirmation in an external cohort. Second, as described above, the indication for the administration of either sorafenib or sunitinib was not determined according to strictly established criteria, which may have affected the findings of this study. Third, it may be necessary to re-analyze the outcomes of first-line TKI therapy after the accumulation of data from patients who received pazopanib, a recently approved TKI with a potential activity against systemic therapy-naive RCC. Finally, this study focused on prognostic issues; however, the usefulness of each agent should be evaluated more comprehensively considering other characteristics, such as those associated with AEs, quality of life and health economy.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically assess the oncological outcome with TKIs introduced as first-line molecular-targeted agents for Japanese patients with mRCC and the outcomes presented in this study appear to be encouraging with respect to cancer control by TKIs for Japanese mRCC patients based on real-world clinical practice. Furthermore, the OS of Japanese mRCC patients receiving TKIs as first-line molecular targeted therapy may be precisely stratified according to the positivity for independent prognostic risk factors identified by multivariate analysis, including the MSKCC classification, CRP level and liver metastasis. Accordingly, these findings strongly suggest the utility of TKIs in the majority of systemic therapy-naive mRCC patients; however, it is necessary to perform an external validation study to draw definitive conclusions regarding the issues presented in this study.

References

- 1.Parton M, Gore M, Eisen T. Role of cytokine therapy in 2006 and beyond for metastatic renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5584–5592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Figlin R, Sternberg C, Wood CG. Novel agents and approaches for advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2012;188:707–715. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.04.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1931–1939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61613-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:722–731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patard JJ, Pignot G, Escudier B, et al. ICUD-EAU International Consultation on Kidney Cancer 2010: treatment of metastatic disease. Eur Urol. 2011;60:684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gore ME, Szczylik C, Porta C, et al. Safety and efficacy of sunitinib for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: an expanded-access trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:757–763. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harshman LC, Xie W, Bjarnason GA, et al. Conditional survival of patients with metastatic renal-cell carcinoma treated with VEGF-targeted therapy: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:927–935. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70285-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck J, Procopio G, Bajetta E, et al. Final results of the European Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Sorafenib (EU-ARCCS) expanded-access study: a large open-label study in diverse community settings. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1812–1823. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5794–5799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choueiri TK, Duh MS, Clement J, et al. Angiogenesis inhibitor therapies for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: effectiveness, safety and treatment patterns in clinical practice-based on medical chart review. BJU Int. 2010;105:1247–1254. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyake H, Miyazaki A, Harada K, et al. Assessment of efficacy, safety and quality of life of 110 patients treated with sunitinib as first-line therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: experience in real-world clinical practice in Japan. Med Oncol. 2014;31:978. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0978-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, et al. Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:289–296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ainsworth NL, Lee JS, Eisen T. Impact of anti-angiogenic treatments on metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:1793–1805. doi: 10.1586/era.09.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.You D, Jeong IG, Ahn JH, et al. The value of cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the era of targeted therapy. J Urol. 2011;185:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beuselinck B, Vano YA, Oudard S, et al. Prognostic impact of baseline serum C-reactive protein in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) treated with sunitinib. BJU Int. 2014;114:81–89. doi: 10.1111/bju.12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon WA, Cho IC, Yu A, et al. Validation of the MSKCC and Heng risk criteria models for predicting survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4397–4404. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyake H, Kusuda Y, Harada K, et al. Third-line sunitinib following sequential use of cytokine therapy and sorafenib in Japanese patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18:81–86. doi: 10.1007/s10147-011-0347-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]