Abstract

Previous epidemiological studies investigating the association between tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer have yielded inconsistent results. Therefore, we aimed to assess this association by conducting a meta-analysis of all available studies. A search was conducted through Pubmed, Embase, Chinese Biomedical literature Database and China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database to identify relevant studies on tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer. A random-effects model was used to calculate the overall combined risk estimates. Six studies (4 case-control and 2 cohort studies), involving a total of 753 patients and 115,349 controls, were included in this meta-analysis. The overall combined odds ratio (OR) for tea consumption and gallbladder cancer was 0.67 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.40–1.12, P=0.13]. Similar results were obtained for the high or moderate tea consumption vs. the low/non-consumption groups. However, our meta-analysis identified a significant association between tea consumption and reduced gallbladder cancer risk in women (OR=0.46, 95% CI: 0.26–0.81, P=0.008), but not in men (OR=0.43, 95% CI: 0.12–1.59, P=0.21). Therefore, the results of the present meta-analysis suggest that, according to the currently available epidemiological studies, tea consumption may reduce the risk of gallbladder cancer in women, but not in men. Further epidemiological studies are required to determine the association between tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer.

Keywords: tea consumption, gallbladder carcinoma, meta-analysis, epidemiological studies

Introduction

Gallbladder cancer is a rare and highly fatal disease and is the most common malignant neoplasm of the extrahepatic biliary tract and the seventh most common gastrointestinal carcinoma (1). There were an estimated 10,310 cases of gallbladder cancer diagnosed in 2013 (2). Although gallbladder cancer remains an uncommon disease, it exhibits a high incidence in certain regions, such as Chile, where it is the most common cause of cancer-related mortality (3). We previously demonstrated the significance of lymph node metastasis (4). Although the etiology of the gallbladder cancer remains unknown, genetic, environmental and infectious factors, as well as the presence of gallstones, are considered to play important roles (5). The majority of the risk factors implicated in the development of gallbladder cancer are associated with inflammation (6).

Tea is one of the most popular beverages worldwide, second only to water, and is obtained from the steamed or pan-fried leaves of Camellia sinensis (7). Tea contains several polyphenols, known as catechins, such as epigallocatechin-3 gallate (EGCG), epigallocatechin (EGC) and epicatechin-3 gallate (ECG), which are considered to prevent the development of certain human diseases (8). Previous cellular and animal xenograft studies have reported that tea or its active components, EGCG, EGC and ECG, may possess antiproliferative, antimutagenic, antioxidant and antibacterial properties (9–13). In general, tea may prevent multifarious cancers at the cell and animal level. Tea was found to induce the apoptosis of gbc-sd human gallbladder carcinoma cells (14,15).

The results of epidemiological studies, such as cohort and case-control studies, investigating the association between tea consumption and gallbladder cancer risk over the last century, have been inconsistent. Certain studies reported that tea consumption significantly decreased the risk of gallbladder cancer, whereas others reported a non-significant negative correlation (16–21). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is currently no published meta-analysis investigating the association between tea consumption and gallbldder cancer risk.

The aim of the present study was to assess the association between tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer through conducting a meta-analysis of relevant case-control and cohort studies.

Materials and methods

Literature search

A literature search was conducted through Pubmed, Embase, Chinese Biomedical literature Database (CBM) and China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database (CNKI), to identify epidemiological studies investigating the association of tea consumption with gallbladder cancer risk. As regards the outcome, the articles were identified using the medical subject headings (mesh) terms ‘gallbladder neoplasm’ or ‘gallbladder carcinoma’ or ‘gallbladder cancer’ and ‘tea’ or ‘polyphenols’. As regards study design, the articles were identified using the mesh terms ‘case-control’ or ‘cohort’ or ‘prospective studies’. The reference lists of the retrieved articles were manually searched to identify potentially relevant publications. All the studies meeting the eligible criteria listed below were included in our meta-analysis.

Inclusion criteria

We reviewed the abstracts of all the identified studies. Further study selection was performed using the following inclusions: i) the exposure of interest was tea consumption; ii) the outcome of interest was gallbladder cancer; iii) the design of the study was cohort, case-control or prospective; and iv) the odds ratio (OR), relative risk or hazard ratio were reported.

The search only involved studies conducted on humans and the publication language was restricted to English and Chinese. If publications were duplicated or shared in more than one study using a different language, we selected the most recent edition and English.

Data extration

Two reviewers (G.W.Z. and J.H.) independently extracted data on the characteristics of the eligible studies retrieved from the databases according to the above mentioned selection criteria, using a standardized data extraction form. The following data were recorded: author name, study design, country, sample size, study period, exposure to tea consumption and study results. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus with a third author (Z.J.W.).

Statistical analyses

OR with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used as a common measure of the association between tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer across studies. For the purposes of the present analysis, tea consumption was coded as a three-level indicator variable, with non/low, moderate and high consumption (Table I). We investigated possible heterogeneity in the results across the studies using the Cochran's Q test. The I2 statistic, which is a quantitative measure of inconsistency across publications, was also used (22). Studies with an I2 statistic of 25–50, 50–75 and >75% were considered to exhibit low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively (22). The random-effects model was used when significant (moderate and high) heterogeneity was observed among studies (23). Potential publication bias was assessed by visually inspecting the Begg's funnel plots. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. All the statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager software, version 5.2 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Table I.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study (year) | Design | Study period | Country | No. of cases/controls | Low/non-consumption | Moderate consumption | High consumption | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nechuta et al (2012) | Cohort | 1996–2000 | China | 83/69,310 | Never | NR | Current | (16) |

| Yen et al (1987) | Case-control | 1975–1979 | USA | 67/272 | Never/occasionally/1–2 cups/day | 3–4 cups/day | ≥5 cups/day | (17) |

| Nagano et al (2001) | Cohort | 1979–1994 | Japan | 122/38,540 | 0–1 times/day | 2–4 times/day | ≥5 times/day | (18) |

| Zhang et al (2006) | Case-control | 1997–2001 | China | 368/902 | Never | M: <81,600 g lifetime; | M: >81,600 g lifetime; | (19) |

| F: <24,600 g lifetime | F: <24,600 g lifetime | |||||||

| Zatonski et al (1992) | Case-control | 1985–1988 | Poland | 72/184 | Never | <6,570 lifetime drinks | >6,570 lifetime drinks | (20) |

| La Vecchia et al (1992) | Case-control | 1983–1990 | Italy | 41/6,141 | No tea consumption | NR | Tea consumption | (21) |

NR, not reported; M, male; F, female.

Results

Identification of relevant studies

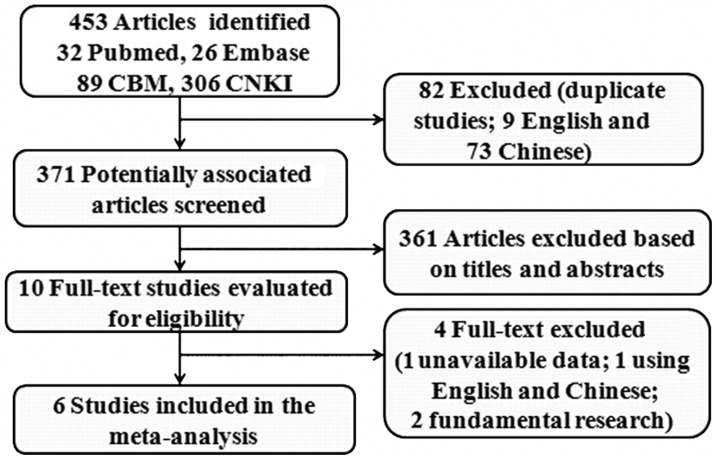

Our meta-analysis included a total of 6 studies [4 case-control (17,19–21) and 2 cohort studies (16,18)] published between 1987 and 2012. The literature search and selection process is summarized in Fig. 1. The four databases (Pubmed, Embase, CBM and CNKI) and the search through the bibliographies of relevant articles yielded 453 articles. A total of 82 articles were excluded due to being duplicate studies. The remaining 371 articles were reviewed; of these, the majority were excluded following title and abstract review (reviews, letters, or studies not relevant to our meta-analysis were excluded), leaving 10 studies for full-text review. A further 2 studies were excluded [one study with unavailable data for analysis (24) and one study published using English and Chinese (25)]. Following fundamental research exclusion of another 2 studies (14,15), a total of 6 studies were included in our present meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the literature search and study selection process.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 6 studies included in this meta-analysis are summarized in Table I. The case/control sample size of the studies ranged between 41/184 and 368/69,310. Among these studies, 1 study only enrolled a female population (16). The definition of tea consumption level (high/moderate vs. low/non-consumption) are also reported in Table I.

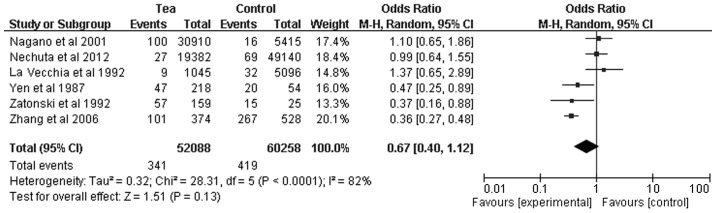

Tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer

A total of 6 studies were included in the meta-analysis investigating the association between tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer. Overall, no significant association was observed between tea consumption and gallbladder cancer risk (OR=0.67, 95% CI: 0.40–1.12, P=0.13) in a random-effects model. There was significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2=82%; P<0.0001) (Fig. 2). Subsequently, sensitivity analyses were conducted to identify the potential source of heterogeneity and to assess the effect of different exclusion criteria on the combined estimates. Exclusion of women from studies on tea and gallbladder cancer risk yielded similar results (OR=0.62, 95% CI: 0.35–1.10, P=0.10), with significant heterogeneity (I2=81%; P=0.0003) (16). Following exclusion of 3 studies with a small sample size, the pooled results were not affected (OR=1.09, 95% CI: 0.80–1.48, P=0.60) and no significant heterogeneity was observed among the remaining studies (I2=0%; P=0.76) (17,19,20).

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the risk estimates from case-control and cohort studies assessing the association between tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer. CI, confidence interval.

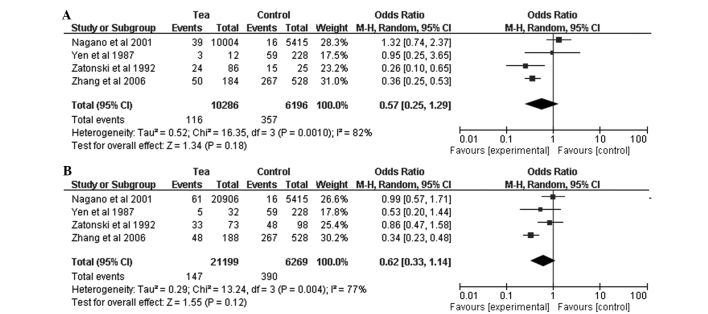

Levels of tea consumption and gallbladder cancer risk

We performed meta-analyses based on the level of tea consumption to investigate the effect of different tea consumption levels on gallbladder cancer risk. The results were relatively consistent and demonstrated that there was no significant difference bettween high/moderate vs. low/non-consumption in reducing the risk of gallbladder cancer (OR=0.57, 95% CI: 0.25–1.29, P=0.18; Fig. 3A; and OR=0.62, 95% CI: 0.33–1.14, P=0.12; Fig. 3B, respectively).

Figure 3.

(A) Forest plot showing the risk estimates for high vs. low/non-consumption of tea and the risk of gallbladder cancer. (B) Forest plot showing the risk estimates for moderate vs. low/non-consumption of tea and the risk of gallbladder cancer. CI, confidence interval.

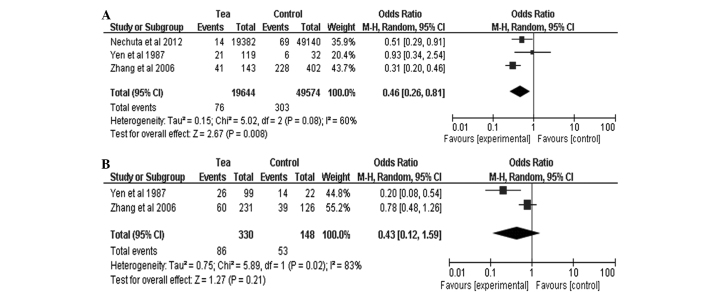

Comparison of women and men regarding tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer

When studies were divided by gender, there was a significant decrease in the risk of gallbladder cancer associated with tea consumption in women (OR=0.46, 95% CI: 0.26–0.81, P=0.008; Fig. 4A). However, no association between tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer was observed in men (OR=0.43, 95% CI: 0.12–1.59, P=0.21; Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

(A) Forest plot showing the risk estimates for tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer in women. (B) Forest plot showing the risk estimates for tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer in men. CI, confidence interval.

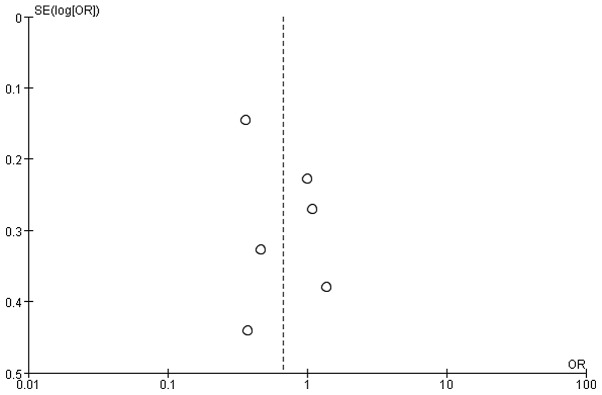

Publication bias

In our meta-analysis, the potential presence of publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of the Begg's funnel plots, which indicated that there was no significant publication bias (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of tea consumption and the the risk of gallbladder cancer. OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the association between tea consumption and gallbladder cancer. This meta-analysis of epidemiological studies (4 case-control and 2 cohort studies) investigating the association between tea and gallbladder cancer risk, demonstrated that tea consumption did not reduce the risk of gallbladder cancer. Similar results were obtained for high or moderate vs. low/non-consumption. However, our meta-analysis identified a significant association between tea consumption and reduced gallbladder cancer risk in women, but not in men. The combined estimates were robust across sensitivity analyses and exhibited no publication bias.

A number of studies conducted in vitro and in vivo reported that tea may protect against different types of cancer (26–31). Therefore, several clinical and epidemiological studies were conducted, which, however, yielded conflicting results regarding tea consumption and the risk of breast (32,33), lung (34) and renal cancer (35,36). In order to obtain more convincing results, certain meta-analyses were conducted for other types of cancer, which also yielded inconsistent results (37–40).

The results of the epidemiological studies on the association between tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer included in our meta-analysis were inconsistent: 2 studies reported that tea intake decreased the risk of gallbladder cancer (17,20), 3 studies reported opposing results (16,18,21) and 1 study reported that tea intake reduced the risk of gallbladder cancer in women, but not in men (19). Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis assessing the association between tea consumption and gallbladder cancer.

Our meta-analysis found that there was a significant association between tea consumption and reduced gallbladder cancer risk in women, but not in men. There may be a reasonable explanation for this finding: lifestyle factors, such as smoking and alcohol consumption may be responsible for the tea intake not reducing the risk of gallbladder cancer in men, due to the high prevalence of smoking and alcohol consumption among men (41,42), which may eliminate the protective effect of tea. Another possible explanation for the significant protective effect of tea in women may be relevant to the effects of tea on estrogen biosynthesis. Previous studies demonstrated that high levels of estrogens were consistently associated with a high risk of gallbladder cancer in women (43–45). Experimental data from animal and cell models suggested that tea may affect estrogen metabolism, although the detailed mechanisms underlying this effect remain unknown (46,47).

As is often the case with meta-analyses, ours had certain limitations. First, our analysis was based on 6 studies with widely variable sample sizes, which may be the origin of the heterogeneity of our meta-analysis. Although we performed a funnel plot for the outcomes, the limited number of studies makes it difficult to explain the result of publication bias. Second, certain detailed information could not be obtained, such as 2 studies that did not provide a precise record of gallbladder cancer cases (16,17), although gallbladder cancer is the most common malignant neoplasm of the extrahepatic biliary tract and accounts for the majority of extrahepatic biliary cancers (1); therefore, the studies were included in our meta-analysis. Moreover, there are several types of tea, including green, oolong and black tea, which may inhibit cancer development through different mechanisms. Therefore, our study results may not apply to all types of tea. Finally, missing and/or unpublished data may lead to bias.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis suggests that, according to the currently available epidemiological studies, tea consumption may reduce the risk of gallbladder cancer in women, but not in men. Due to the limitations of our study, further epidemiological studies are required to determine the association between tea consumption and the risk of gallbladder cancer.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81272373), the Key Project of Science and Technology Research Program of Fujian Province (no. 2009Y0024), the Key Project of Science Research of Fujian Medical University (no. 09ZD017) and the National Clinical Key Specialty Construction Project (General Surgery) of China.

References

- 1.Donohue JH, Stewart AK, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on carcinoma of the gallbladder, 1989–1995. Cancer. 1998;83:2618–2628. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981215)83:12<2618::AID-CNCR29>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. 2013 CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randi G, Malvezzi M, Levi F, et al. Epidemiology of biliary tract cancers: an update. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:146–159. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du Q, Jiang L, Wang XQ, Pan W, She FF, Chen YL. Establishment of and comparison between orthotopic xenograft and subcutaneous xenograft models of gallbladder carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:3747–3752. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.8.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wernberg JA, Lucarelli DD. Gallbladder cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2014;94:343–360. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albores-Saavedra J, Alcantra-Vazquez A, Cruz-Ortiz H, Herrera-Goepfert R. The precursor lesions of invasive gallbladder carcinoma Hyperplasia, atypical hyperplasia and carcinoma in situ. Cancer. 1980;45:919–927. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800301)45:5<919::AID-CNCR2820450514>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jankun J, Selman SH, Swiercz R, Skrzypczak-Jankun E. Why drinking green tea could prevent cancer. Nature. 1997;387:561. doi: 10.1038/42381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reto M, Figueira ME, Filipe HM, Almeida CM. Chemical composition of green tea (Camellia sinensis) infusions commercialized in Portugal. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2007;62:139–144. doi: 10.1007/s11130-007-0054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jochmann N, Baumann G, Stangl V. Green tea and cardiovascular disease: from molecular targets towards human health. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:758–765. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328314b68b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng S, Ding L, Zhen Y, et al. Progress in studies on the antimutagenicity and anticarcinogenicity of green tea epicatechins. Chin Med Sci J. 1991;6:233–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta S, Saha B, Giri AK. Comparative antimutagenic and anticlastogenic effects of green tea and black tea: a review. Mutat Res. 2002;512:37–65. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5742(02)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert JD, Elias RJ. The antioxidant and pro-oxidant activities of green tea polyphenols: a role in cancer prevention. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;501:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabrera C, Artacho R, Gimenez R. Beneficial effects of green tea - a review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006;25:79–99. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2006.10719518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lian CQ, Zhang J, Chen ZD. Changes of free calcium ion concentration and mitochondrial membrane potential during apoptosis of human gallbladder carcinoma GBC-SD cells induced by tea polyphenols. Chin J Biol. 2012;25:449–452. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lian CQ, Xia J, Gao Q, Zhang J. A study on apoptosis in human gallbladder carcinoma GBC-SD cells induced by tea polyphenols. Chin J Gerontol. 2012;32:2077–2080. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nechuta S, Shu XO, Li HL, et al. Prospective cohort study of tea consumption and risk of digestive system cancers: results from the Shanghai Women's Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:1056–1063. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.031419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yen S, Hsieh CC, MacMahon B. Extrahepatic bile duct cancer and smoking, beverage consumption, past medical history, and oral contraceptive use. Cancer. 1987;59:2112–2116. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870615)59:12<2112::AID-CNCR2820591226>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagano J, Kono S, Preston DL, Mabuchi K. A prospective study of green tea consumption and cancer incidence, Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Japan) Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:501–508. doi: 10.1023/A:1011297326696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang XH, Andreotti G, Gao YT, et al. Tea drinking and the risk of biliary tract cancers and biliary stones: a population-based case-control study in Shanghai, China. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:3089–3094. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zatonski WA, La Vecchia C, Przewozniak K, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB, Boyle P. Risk factors for gallbladder cancer: a Polish case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1992;51:707–711. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910510508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, D'Avanzo B, Boyle P. Tea consumption and cancer risk. Nutr Cancer. 1992;17:27–31. doi: 10.1080/01635589209514170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandey M, Shukla VK. Diet and gallbladder cancer: a case-control study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2002;11:365–368. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang XH, Gao YT, Rashid A, et al. Tea consumption and risk of biliary tract cancers and gallstone disease: a population-based case-control study in Shanghai, China. Chin J Oncol. 2005;27:667–671. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang CS, Maliakal P, Meng X. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by tea. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:25–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.082101.154309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen D, Daniel KG, Kuhn DJ, et al. Green tea and tea polyphenols in cancer prevention. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2618–2631. doi: 10.2741/1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huo C, Wan SB, Lam WH, et al. The challenge of developing green tea polyphenols as therapeutic agents. Inflammopharmacology. 2008;16:248–252. doi: 10.1007/s10787-008-8031-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adhami VM, Siddiqui IA, Sarfaraz S, et al. Effective prostate cancer chemopreventive intervention with green tea polyphenols in the TRAMP model depends on the stage of the disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1947–1953. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bettuzzi S, Rizzi F, Belloni L. Clinical relevance of the inhibitory effect of green tea catechins (GtCs) on prostate cancer progression in combination with molecular profiling of catechin-resistant tumors: an integrated view. Pol J Vet Sci. 2007;10:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scaltriti M, Belloni L, Caporali A, et al. Molecular classification of green tea catechin-sensitive and green tea catechin-resistant prostate cancer in the TRAMP mice model by quantitative real-time PCR gene profiling. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1047–1053. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inoue M, Tajima K, Mizutani M, et al. Regular consumption of green tea and the risk of breast cancer recurrence: follow-up study from the Hospital-based Epidemiologic Research Program at Aichi Cancer Center (HERPACC) Japan. Cancer Lett. 2001;167:175–182. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu AH, Yu MC, Tseng CC, Hankin J, Pike MC. Green tea and risk of breast cancer in Asian Americans. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:574–579. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arts IC, corp-author. A review of the epidemiological evidence on tea, flavonoids, and lung cancer. J Nutr. 2008;138:1561S–1566S. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.8.1561S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Stefani E, Fierro L, Mendilaharsu M, et al. Meat intake, ‘mate’ drinking and renal cell cancer in Uruguay: a case-control study. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:1239–1243. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu J, Mao Y, DesMeules M, Csizmadi I, Friedenreich C, Mery L. Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research Group: Total fluid and specific beverage intake and risk of renal cell carcinoma in Canada. Cancer Epidemiol. 2009;33:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong S, Chen Z, Yu X, et al. Tea consumption and leukemia risk: a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:5205–5212. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1675-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu ZH, Lin YW, Xu X, et al. No association between tea consumption and risk of renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:1691–1695. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.3.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin YW, Hu ZH, Wang X, et al. Tea consumption and prostate cancer: an updated meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:38. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myung SK, Bae WK, Oh SM, et al. Green tea consumption and risk of stomach cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:670–677. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan JM, Sun C, Butler LM. Tea and cancer prevention: epidemiological studies. Pharmacol Res. 2011;64:123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao YT, McLaughlin JK, Blot WJ, Ji BT, Dai Q, Fraumeni JF., Jr Reduced risk of esophageal cancer associated with green tea consumption. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:855–858. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.11.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandey M, Shukla VK. Lifestyle, parity, menstrual and reproductive factors and risk of gallbladder cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:269–272. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200308000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakagaki M, Nakayama F. Effect of female sex hormones on lithogenicity of bile. Jpn J Surg. 1982;12:13–18. doi: 10.1007/BF02469009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen A, Huminer D. The role of estrogen receptors in the development of gallstones and gallbladder cancer. Med Hypotheses. 1991;36:259–260. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(91)90145-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuruto-Niwa R, Inoue S, Ogawa S, Muramatsu M, Nozawa R. Effects of tea catechins on the ERE-regulated estrogenic activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:6355–6361. doi: 10.1021/jf0008487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagai M, Conney AH, Zhu BT. Strong inhibitory effects of common tea catechins and bioflavonoids on the O-methylation of catechol estrogens catalyzed by human liver cytosolic catechol-O-methyltransferase. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:497–504. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.5.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]