Abstract

Lymphocytes have demonstrated complex molecular responses to induced stress by ionizing radiation. Many of these reactions are mediated through modifications in gene expressions, including the genes involved in apoptosis. The primary aim of this study was to assess the effects of low doses of ionizing radiation on the apoptotic genes, expression levels. The secondary goal was to estimate the time-effect on the modified gene expression caused by low doses of ionizing radiation. Mononuclear cells in culture were exposed to various dose values ranged from 20 to 100 mGy by gamma rays from a Cobalt-60 source. Samples were taken for gene expression analysis at hours 4, 24, 48, 72, and 168 following to exposure. Expression level of two apoptotic genes; BAX (pro-apoptotic) and Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic) were examined by relative quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), at different time intervals. Radio-sensitivity of peripheral blood mononucleated cells (PBMCs) was measured by the Bcl-2/BAX ratio (as a predictive marker for radio-sensitivity). The non-parametric two independent samples Mann–Whitney U-test were performed to compare means of gene expression. The results of this study revealed that low doses of gamma radiation can induce early down-regulation of the BAX gene of freshly isolated human PBMCs; however, these changes were restored to near normal levels after 168 hours. In most cases, expression of the Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic gene was up-regulated. Four hours following to exposure to low doses of gamma radiation, apoptotic gene expression is modified, this is manifested as adaptive response. Modification of these gene expressions seems to be a principle pathway in the early radioresistance response. In our study, we found that these changes were temporary and faded completely within a week.

Keywords: Apoptosis, deoxyribose nucleic acid damage, gene expression, ionizing radiation

Introduction

Nowadays human beings are exposed to various sources of ionizing radiation. The level of radiation exposure from environmental and man-made sources (particularly occupational exposure) is measured by various personal dosimeters such as thermoluminescent dosimeter (TLDs), films, and other devices or methods. However, physical dosimeters are not capable to assess unplanned or accidental exposures from occupational, therapeutic or environmental sources. In such circumstances, quantification of biological changes at cellular or molecular levels in the living media may be more appropriate techniques. It is generally believed that deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is the main target when ionizing radiation interactions occur within cells. Thus, principal cell injuries following interactions of ionizing radiation can be attributed to the DNA damages.[1] Cells’ response following DNA damage include cell cycle arrest,[2] DNA repair,[3] and programmed cell death (apoptosis)[4,5] Ionizing-radiation–induced apoptosis involves the B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family and is mediated by extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. The latter is the principal cause of apoptosis,[6] and the Bcl–2 family proteins are the most important component of this pathway.[7] Pro-apoptotic members of Bcl–2 family proteins, such as Bcl-2–associated X protein (BAX) induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization to cause cytochrome-c release, whereas anti-apoptotic members such as Bcl-2 work as protectors of the outer membrane and preserve its integrity by opposing BAX function.[8] These cellular endpoints are considered as biological markers of radio-sensitivity by some researchers. Most of these reactions are mediated through modifications in gene expression, to prevent the conversion of abnormal DNA structures into inheritable mutations, and minimize survival of cells with irreparable damage.[9,10] However, the available data are not consistent and molecular responses to low doses of radiation are poorly characterized.[11] In recent years, variation of gene expression level has been suggested as a biological indicator of ionizing radiation exposure level.[12,13,14,15] In some studies, performed on lymphocytes suggest gene expression level are time-dependent.[16] A good knowledge of post-irradiation history of a biomarker would help to assess absorbed dose, regardless of the elapsed time between exposure and sampling. In vitro studies, mostly have been carried out on peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL), and the elapsed time between irradiation and gene expression assessment varies from 15 minutes to 72 hours.[17]

However, human health risks from exposure to low doses of ionizing radiation remains completely vague, and is the subject of intense debates. In the present study, we have used PBLs to investigate the effect of elapsed time on the modification of gene expression level up to one week following to low doses of ionizing radiation.

Materials and Methods

Blood sampling and lymphocyte culture

Fifty milliliter whole blood samples were collected in individual tubes containing Ethylene Diamine Tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) from male volunteers. PBMCs were separated by Ficoll (Cedarlane) according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. The mononuclear cell layer was removed and washed in Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS). The cells were counted and re-suspended in a 10 ml culture medium, including RPMI 1640 (Gibco) containing 20% FBS (Biosera), 1% of 200 mM L-glutamine (Biosera), 100 Iu/ml penicillin, 0.1 μg/ml Streptomycin. Cells were transferred to four 25 cm3 flasks (Spl) in a final cell concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml.

Gamma irradiation

Dosimetry study was performed with Farmer-type 0.6 cm3 ionization chamber with a Farmer 2581 electrometer. Each sample was divided into four flasks. Three flasks were exposed to a Co-60 (Phoenix Theratron) source at SSD = 80 cm and 13.7 mGy/min. A lead attenuator was used to reduce the output dose rate of the source. This arrangement made it possible to deliver 20, 50, and 100 mGy to a selected flask in a practical time interval. The fourth flask containing the sham control group did not receive any radiation, which was treated exactly similar to the other three flasks. One percent PhytoHaemAgglutinin (PHA) (Gibco) was added to the culture medium following to irradiation, and all irradiated and control samples were incubated at 37oC with 5% Co2 for 1 week as suggested by Falt et al.[18]

RNA preparation

To study patterns of apoptotic genes’ expression in human peripheral blood, lymphocytes were collected for ribonucleic acid (RNA) isolation from cultures 4 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours, 72 hours, and 168 hours following irradiation. The results are expected to help understanding early and delayed apoptotic response to ionizing radiation.

Approximately 3 × 106 lymphocytes were taken for the subsequent isolation of RNA using the TriPure reagent (Roche Applied Science, Germany). The lymphocyte pellets were transferred into 750 μl TriPure reagent. Each sample was incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature and then 150 μl Chloroform (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to it. After vigorous manual shaking for a further 15 seconds, all samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. To separate the solution into three phases, the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 minutes at 4oC. The colorless upper aqueous phase was transferred to a new centrifuge tube and 350 μl Isopropanol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to it, then samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes to allow the RNA precipitate to form. The solution was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 minutes at 4oC. The supernatant was discarded, and the RNA pellets were washed with 75% Ethanol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), air-dried, and then resuspended in 20 μL DiEthylPyroCarbonate (DEPC)-treated RNase-free water.

cDNA synthesis

Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed in a total volume of 20 μl, containing 200 U of M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase, 4 μl of 5 × Reaction Buffer, 20 U of Ribolock™ RNase inhibitor, 2 μl of Deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate (final 1 mM), 1 μl of oligo (dt) 18 primer (0.5 μg), and 1 μg of total RNA. The prepared template with the control Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) RNA and GAPDH control primers (1.3 kb) were used as a positive control, and no negative template control was prepared with total reagent for the reverse transcription reaction, except for the RNA template. cDNA was synthesized according to the manufacturer recommendations (RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, Fermentas). Each cDNA was amplified by control polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction using primers for the GAPDH according to the manufacturer protocol (Prime Taq DNA polymerase, Genet Bio, South Korea). Five microliter of PCR product was loaded on 1% agarose gel and a distinct 496 bp was observed after Ethidium Bromide staining.

Gene expression analyses by real-time PCR

Real-time RT-PCR reactions were carried out in a MicroAmp™ Fast Optical 48-well reaction plate with Optical Adhesive Film (Applied Biosystems) as duplicates in a total volume of 15 μl, containing cDNA (1.5 μl), forward and reverse primers (300 nM), SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (7.5 μl) and ROX™ Reference Dye II (0.3 μl) (Takara, Japan) and dH2O 5.1 μl. Gene expression assessments were performed on a StepOne (48-well) Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The samples were thermally cycled under the following conditions: First holds at 95°C for 60 seconds, followed by cycling at 95°C for 10 seconds (for 40 cycles) and finally 60°C for 30 seconds. After each run, the result was analyzed automatically once, with Step One software v. 2.1 (Applied Biosystems). The relative standard curve method was applied for cDNA quantification. This approach gives rise to a highly accurate quantitative results (quantity of an unknown sample is acquired from interpolation of the standard curves. The curve produced from the same samples for each plate)[19] The quantity of the target genes was normalized by quantity of Beta-2 Microglobulin (β2M) as the endogenous control gene (β2M was used as the housekeeping or “stably expressed” gene). To obtain final relative quantity (RQ); the normalized quantity of the treated samples were compared with the normalized quantity of the control sample. Primers were purchased from Metabion (Martinsried, Germany). Primer sequences were: β2M forward 5’- GTA TGC CTG CCG TGT GAA C-3’, reverse 5’- AAC CTC CAT GAT GCT GCT TAC-3’; Bcl-2 forward 5’- TAC TTA AAA AAT ACA ACA TCA CAG-3’, reverse 5’- GGA ACA CTT GAT TCT GGT G-3’; BAX forward 5’- GCT TCA GGG TTT CAT CCA G-3’, reverse 5’- GGC GGC AAT CAT CCT CTG-3’.

Results

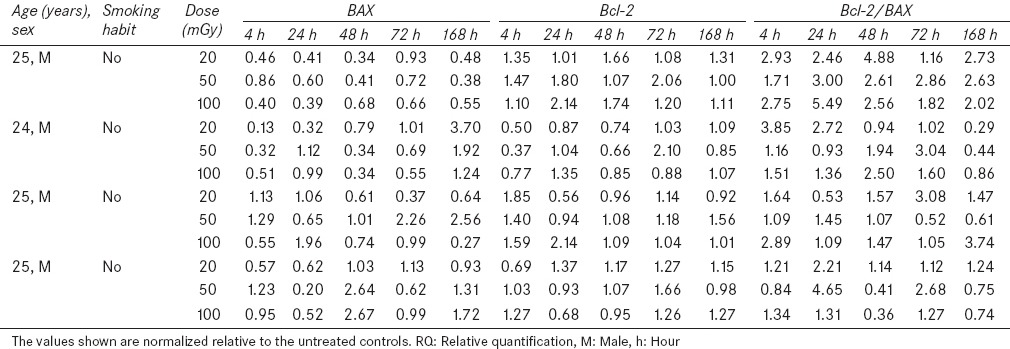

Human whole blood samples were collected from four healthy volunteers, without any history of radiation therapy and they received no medication during this study [Table 1]. Relative quantitative RT-PCR method was employed to compare gene expression levels of treated and control groups. The results were expressed as the means and standard errors of the means (S.E.). All data were analyzed by Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 11.5 software. Mann–Whitney U-test was performed to compare average of gene expression level for irradiated and control groups, a P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

Characterization of donors, gene expression level (RQ) and Bcl-2/BAX ratio

Effects of low-dose gamma radiation on Bcl-2 and BAX genes

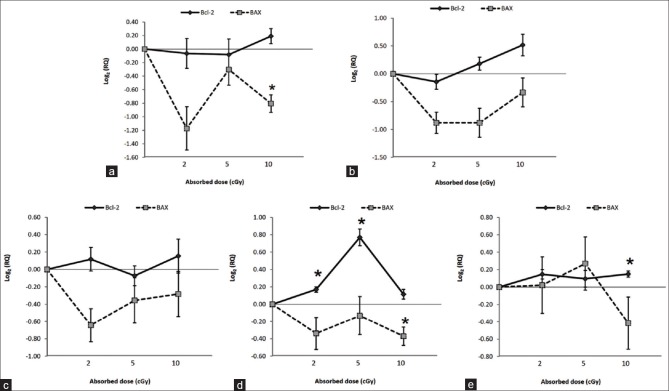

The results indicate that when lymphocytes are exposed to 20, 50, and 100 mGy of gamma radiation; down-regulation is induced for BAX pro-apoptotic gene 4 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours following irradiation [Figure 1a–d]. Expression of Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic gene was found to be up-regulated at doses as low as 20 mGy after 48 hours, 72 hours, and 168 hours following irradiation [Figure 1c–e]. The results also show that the Bcl-2 expression was induced by 50 mGy at 24 hours [Figure 1b], 72 hours [Figure 1d], and 168 hours [Figure 1e] following irradiation. In addition, up-regulation of Bcl-2 expression was induced by 100 mGy at 4 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours, 72 hours, and 168 hours after irradiation [Figure 1a–e].

Figure 1.

Effect of Gamma radiation of 0–100 mGy on BAX and Bcl-2 expression in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. (a) 4 h (b) 24 h (c) 48 h (d) 72 h (e) 168 h post-irradiation. Each point represents mean value for the four blood samples. Gene expression data are given in terms of the base 2 logarithm of the ratio; positive and negative values represent increased and decreased expression level, respectively. *represents statistically significant difference from controls at P<0.05 and Error bars show standard deviation

Effect of elapsed time on Bcl-2 and BAX gene expression following exposure

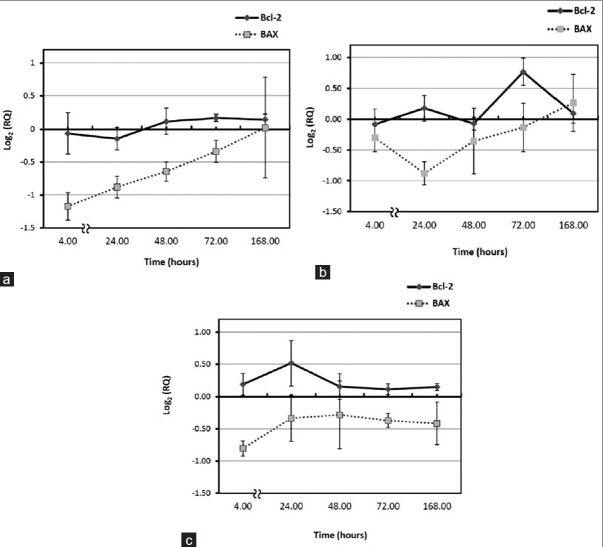

In this study, the effect of elapsed time following exposure was also examined. Early down-regulation of BAX gene expression induced by 20, 50, and 100 mGy, 4 hours following irradiation is shown in Figure 2a–c. This phenomenon was terminated 168 hours after delivery of 20 and 50 mGy. Maximum reduction in BAX gene expression was observed 4 hours following to 20 and 100 mGy [Figure 2a and b], similar result was observed 24 hours after 50 mGy [Figure 2c]. Low doses of gamma gave rise to up-regulation of Bcl-2 expression. The highest increase was noticed at 72 hours following to 50 mGy [Figure 2b], this was also true for delivery of 100 mGy at 24 hours after irradiation [Figure 2c].

Figure 2.

Effect of elapsed time on relative quantification (RQ) after irradiation to (a) 20 mGy, (b) 50 mGy, and (c) 100 mGy. Gene expression results are presented in terms of the base-2 logarithm of the RQ; positive and negative values represent increased and decreased gene expression level, respectively. Each point represents the mean of four individual experiments and error bars show the S.E

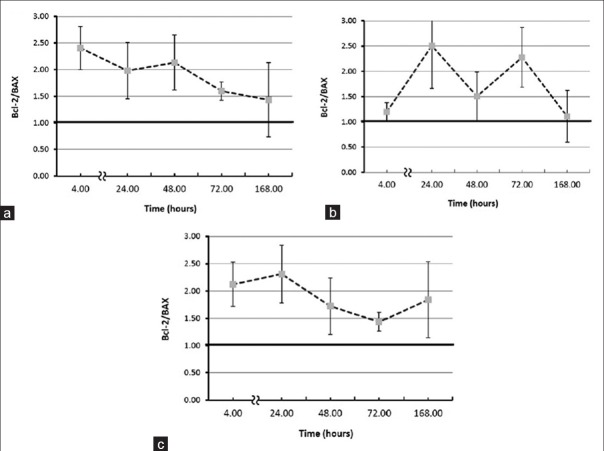

Low-dose irradiation alters radio-sensitivity

The Bcl-2/BAX ratio has been introduced as a predictive marker for therapeutic response to radiotherapy and radio-sensitivity.[20,21,22] Particularly, the high ratio is considered as a crucial factor of cell resistance to apoptosis. This means that the sensitive cells are characterized by low Bcl-2/BAX ratio and resistant cells by high ratio.[23] In other words, low doses of gamma radiation reduces radio-sensitivity of human peripheral blood lymphocytes. This is shown in Figure 3 (a-c). Maximum rise in the Bcl-2/BAX ratio was observed 4 hours following to 20 and 100 mGy. Nevertheless, this phenomenon changed course and was almost eliminated 168 hours after 20 mGy gamma irradiation. However, this result may reflect the inter-individual variability between the donors [Table 1].

Figure 3.

Effect of elapsed time on Bcl-2/BAX ratio (a) 20 mGy, (b) 50 mGy, and (c) 100 mGy post-irradiation. Each point represents the mean of four individual experiments and error bars show the S.E

Conclusion

Bcl-2 family proteins control the cell response to radiation and regulate apoptosis.[24,25] Anti-apoptotic members of Bcl-2–family proteins are Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, Bcl-w, Mcl-1, Bfl1/A-1, and Bcl-B. Also, some pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2-family proteins are BAX, Bak, and Bok.[26] The intrinsic pathway of apoptosis by adjusting the release of mitochondrial proteins, including cytochrome-c (cyt. c) controls the occurrence of apoptosis.

The maximal induction appeared between 2–3 hours post-exposure for BAX in the human myeloid leukemia cell line ML-1 that was irradiated at approximately 51 mGy/min (total doses of 20–500 mGy of gamma rays), then rapidly declined to near control levels within 24 hours.[27] While our study demonstrated that the expression peak of BAX is decreased at lower dose rates (13.7 mGy/min) (total doses of 20 and 100 mGy) at 4 hours post-exposure, also for 50 mGy at 24 hours post-exposure. On the other hand, a significant decrease in the expression level of BAX was observed in human PBMCs 4 hours post-exposure to 100 mGy. Although these changes faded with elapsed time, but a significant reduction in the expression level of the BAX gene was still noticed 72 hours following to 100 mGy dose.

In previous studies, the induction kinetics of apoptosis in vitro indicated that a maximum is reached approximately 72 hours after irradiation;[28] in another study, a significant induction of apoptosis in T-cells was observed 44 hours after delivery of 300 mGy.[29]

BAX as a pro-apoptotic member of Bcl-2–family proteins, induces mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, to cause cytochrome-c release and the occurrence of apoptosis.[30] These results show that low doses of ionizing radiation lead to reduction of mitochondrial cytochrome-c release and prevent apoptosis. However, in already studies, the lowest dose level at which the radiation-induced apoptosis frequency was still significantly above control was 50 mGy.[28,31]

Some studies have demonstrated down-regulation of Bcl-2 expression and up-regulation of BAX expression following high doses of ionizing radiation.[32] However, the result of this study indicates that the expression of BAX was found to be down-regulated at low doses of ionizing radiation, and Bcl-2 was up-regulated by 20 mGy at 48 hours, 72 hours, and 168 hours, by 50 mGy at 24 hours, and also by 100 mGy, until a week after irradiation. Bcl-2 works as a protector of the outer membrane and preserves its integrity by opposing BAX.[30] Bcl-2 expression is appreciably increased 72 hours following irradiation to 20 and 50 mGy, same effect is observed 168 hours after PBL samples is irradiated by 100 mGy (P < 0.05). Furthermore, there were no more statistically significant difference between BAX and Bcl-2 expression levels of irradiated and control samples. On the other hand, over expression of the Bcl-2 protein has been reported for many types of human cancers, including leukemia, lymphoma, and carcinoma.[33]

The Bcl-2/BAX ratio was significantly increased 4 and 72 hours following irradiation 20 mGy, and 4 hours, 24 hours, and 72 hours following irradiation 100 mGy (P < 0.05).

The results of the present study have shown that low doses of gamma radiation can increase the Bcl-2/BAX ratio. This means that, although high doses of gamma radiation can cause apoptosis, the observed increase of the Bcl-2/BAX ratio is an indication that low doses of gamma radiation cause reduction of lymphocyte radio-sensitivity. Several researchers assessed cell radio-sensitivity by examining the level of apoptosis, they realized that it depends not only on dose value, but also on post-exposure elapsed time.[29,34] Some studies have suggested time-dependent expression,[16] particularly in the first 5 hours and a return to the base-line within 20 hours.[35] But, in our study, these changes remained for a much long time and gradually faded over a week. Although, biological responses to low-dose ionizing radiation are exhibited in several ways, adaptive response is considered one of them.[36] Induction of radio-adaptive response by low-level ionizing radiation was previously reported for protection against radiation induced chromosomal aberrations in human lymphocytes.[37] Our results could support the hypothesis that the radioresistance effects of low dose exposure may be due to the up-regulated expression of Bcl-2 genes that may provide a survival advantage. Although other cellular radio-protection mechanisms may be involved, such as alterations in the levels of some cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins, DNA repair, and other processes. There are some limitations in this study, the main one being the interindividual variability between the donors. It has to be emphasized that the results presented in this article are preliminary results of an ongoing research work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the office of vice president for research of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences for funding this work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Roos WP, Kaina B. DNA damage-induced cell death by apoptosis. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:440–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khanna KK, Jackson SP. DNA double-strand breaks: Signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nat Genet. 2001;27:247–54. doi: 10.1038/85798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins AR, Ferguson LR. DNA repair as a biomarker. Mutat Res. 2012;736:2–4. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valerie K, Yacoub A, Hagan MP, Curiel DT, Fisher PB, Grant S, et al. Radiation-induced cell signaling: Inside-out and outside-in. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:789–801. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dainiak N, Schreyer SK, Albanese J. The search for mRNA biomarkers: Global quantification of transcriptional and translational responses to ionising radiation. BJR Suppl. 2005;27:114–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown JM, Wilson G. Apoptosis genes and resistance to cancer therapy: What does the experimental and clinical data tell us? Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:477–90. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.5.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed JC, Pellecchia M. Apoptosis-based therapies for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2005;106:408–18. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furlong H, Mothersill C, Lyng FM, Howe O. Apoptosis is signalled early by low doses of ionizing radiation in a radiation-induced bystander effect. Mutat Res. 2013;741:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin J, Li L. Molecular anatomy of the DNA damage and replication checkpoints. Radiat Res. 2003;159:139–48. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0139:maotdd]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang C, Kang C, Wang P, Cao Y, Lv Z, Yu S, et al. MicroRNA-221 and-222 regulate radiation sensitivity by targeting the PTEN pathway. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80:240–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pernot E, Hall J, Baatout S, Benotmane MA, Blanchardon E, Bouffler S, et al. Ionizing radiation biomarkers for potential use in epidemiological studies. Mutat Rest. 2012;751:258–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turtoi A, Brown I, Oskamp D, Schneeweiss FH. Early gene expression in human lymphocytes after gamma-irradiation-a genetic pattern with potential for biodosimetry. Int J Radiat Biol. 2008;84:375–87. doi: 10.1080/09553000802029886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grace MB, McLeland CB, Blakely WF. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR assay of GADD45 gene expression changes as a biomarker for radiation biodosimetry. Int J Radiat Biol. 2002;78:1011–21. doi: 10.1080/09553000210158056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amundson SA, Fornace AJ., Jr Gene expression profiles for monitoring radiation exposure. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2001;97:11–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Templin T, Paul S, Amundson SA, Young EF, Barker CA, Wolden SL, et al. Radiation-induced micro-RNA expression changes in peripheral blood cells of radiotherapy patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80:549–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anglin EJ, Salisbury C, Bailey S, Hor M, Macardle P, Fenech M, et al. Sorted cell microarrays as platforms for high-content informational bioassays. Lab Chip. 2010;10:3413–21. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00185f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy L, Gruel G, Vaurijoux A. Cell response to ionising radiation analysed by gene expression patterns. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2009;45:272–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falt S, Holmberg K, Lambert B, Wennborg A. Long-term global gene expression patterns in irradiated human lymphocytes. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1837–45. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Squassina A, Congiu D, Manconi F, Manchia M, Chillotti C, Lampus S, et al. The PDLIM5 gene and lithium prophylaxis: An association and gene expression analysis in Sardinian patients with bipolar disorder. Pharmacol Res. 2008;57:369–73. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhuo E, He J, Wei T, Zhu W, Meng H, Li Y, et al. Down-regulation of GnT-V enhances nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell CNE-2 radiosensitivity in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Biophs Res Commun. 2012;424:554–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lövey J, Nie D, Tóvári J, Kenessey I, Tímár J, Kandouz M, et al. Radiosensitivity of human prostate cancer cells can be modulated by inhibition of 12-lipoxygenase. Cancer Lett. 2013;335:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scopa CD, Vagianos C, Kardamakis D, Kourelis TG, Kalofonos HP, Tsamandas AC. bcl-2/BAX ratio as a predictive marker for therapeutic response to radiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer. Appl Immunohisto Mol Morphol. 2001;9:329–34. doi: 10.1097/00129039-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raisova M, Hossini AM, Eberle J, Riebeling C, Wieder T, Sturm I, et al. The BAX/Bcl-2 ratio determines the susceptibility of human melanoma cells to CD95/Fas-mediated apoptosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:333–40. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reed JC. Bcl-2 family proteins. Oncogene. 1998;17:3225–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reed JC. Bcl-2–family proteins and hematologic malignancies: History and future prospects. Blood. 2008;111:3322–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-078162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang MH, Reynolds CP. Bcl-2 inhibitors: Targeting mitochondrial apoptotic pathways in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1126–32. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amundson SA, Do KT, Fornace AJ., Jr Induction of stress genes by low doses of gamma rays. Radiat Res. 1999;152:225–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boreham DR, Gale KL, Maves SR, Walker JA, Morrison DP. Radiation-induced apoptosis in human lymphocytes: Potential as a biological dosimeter. Health Phys. 1996;71:685–91. doi: 10.1097/00004032-199611000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkins RC, Wilkinson D, Maharaj HP, Bellier PV, Cybulski MB, McLean JR. Differential apoptotic response to ionizing radiation in subpopulations of human white blood cells. Mutat Res. 2002;513:27–36. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(01)00290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korsmeyer SJ, Wei MC, Saito M, Weiler S, Oh K, Schlesinger P. Pro-apoptotic cascade activates BID, which oligomerizes BAK or BAX into pores that result in the release of cytochrome c. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:1166–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menz R, Andres R, Larsson B, Ozsahin M, Trott K, Crompton NE. Biological dosimetry: The potential use of radiation-induced apoptosis in human T-lymphocytes. Radiat Environ Biophs. 1997;36:175–81. doi: 10.1007/s004110050069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harima Y, Harima K, Shikata N, Oka A, Ohnishi T, Tanaka Y. BAX and Bcl-2 expressions predict response to radiotherapy in human cervical cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1998;124:503–10. doi: 10.1007/s004320050206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cimmino A, Calin GA, Fabbri M, Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Shimizu M, et al. miR-15 and miR-16 induce apoptosis by targeting BCL2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13944–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506654102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkins RC, Kutzner BC, Truong M, McLean JR. The effect of the ratio of CD4+to CD8+T-cells on radiation-induced apoptosis in human lymphocyte subpopulations. Int J Radiat Biol. 2002;78:681–8. doi: 10.1080/09553000210144475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fenech M. Current status, new frontiers and challenges in radiation biodosimetry using cytogenetic, transcriptomic and proteomic technologies. Radiat Meas. 2011;46:737–41. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren R, He M, Dong C, Xie Y, Ye S, Yuan D, et al. Dose response of micronuclei induced by combination radiatison of α-particles and g-rays in human lymphoblast cells. Mutat Res. 2013;741-742:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolff S. The adaptive response in radiobiology: Evolving insights and implications. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:277–83. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106s1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]