Introduction

Episode-based, “bundled” payments have come to the forefront of the national discussion on combating rising health care costs. In the currently dominant, fee-for-service model for reimbursement, hospitals, physicians, and post-acute care providers file distinct claims and are paid separately for provided services even when they are related to a single episode of care. However, this approach to payment encourages fragmented care, with little incentive for resource stewardship, coordination or communication across multiple providers. In contrast, bundled payments seek to align the interests of providers by providing a fixed payment for all services provided during a single episode of care; this payment is distributed among all providers in a health care system involved with that patient, including hospitals and other facilities. Although not a new policy initiative, bundled payments have resurfaced in the current era of health care reform with its advocates arguing that it can curtail health care costs while simultaneously improving quality.

Cardiovascular care is the arena in which implementation of bundled payments are arguably most visible and may be most impactful. Many previous demonstrations of bundled payments have concentrated on cardiovascular conditions, and it is likely that future efforts will continue to do so with good reason. First, cardiovascular diseases are common, costly, and deadly,1 and therefore, important to national discussions for health care reform. Second, care for cardiovascular disease involves multiple providers from different disciplines (primary care, cardiology, cardiac surgery, anesthesiology, radiology). Lastly, cardiovascular patients receive care in multiple health care settings (e.g., hospital, outpatient primary care and subspecialty clinics, skilled nursing facility, etc.). Given all these factors, bundled payments have the potential to substantially improve care coordination and generate savings for cardiovascular care.

In the present article, we further explore bundled payment initiatives and their potential advantages and disadvantages, focusing our review on previous and current bundled payment programs for cardiovascular conditions. We end by discussing what implications these programs might have as health care reforms takes further shape in the coming years.

The Rationale Behind Bundled Payments

Under a typical bundled payment agreement, a health care provider receives a fixed, lump-sum payment to be divided at its discretion among the facilities and providers involved with a discrete episode of care for a given patient. The intent of the policy is to decrease health care spending while maintaining or improving quality of care. Previous studies illustrating large variation in health care costs associated with index hospitalization, physician services, readmissions, and post-acute care have highlighted the potential for cost savings with bundled payments.2–4

Providers (e.g., hospitals, physician groups, etc.) participating in bundled payments agree with payers on a target price for select clinical conditions, typically adjusted for episode severity. To set a target price, payers often look at overall variation and mean pricing in historical payments for all facets of an episode of care to establish a case rate. Payers then enter into negotiations with providers to set a target bundled price, sometimes 1–2% below the case rate or below projected spending growth. Under this model, a participating provider is incentivized to provide efficient care, reducing the number and cost of services contained in the bundle.

In typical bundled payment models, providers and payers share in savings and/or losses. When actual health care costs fall below the lump-sum payment, both parties keep a portion of the difference as additional profit. Conversely, the provider must provide extra services at a loss when health care costs exceed the lump-sum payment, though payers mitigate some of this loss. The potential for savings for payers lies in upfront discounted payments for episodes of care, as well as shared savings with providers when costs fall below the lump-sum payment. In this model for reimbursement, health care systems will be challenged to improve resource stewardship, cooperation and coordination among disparate medical services. Those health care systems that improve the most in these arenas have the greatest potential for savings.

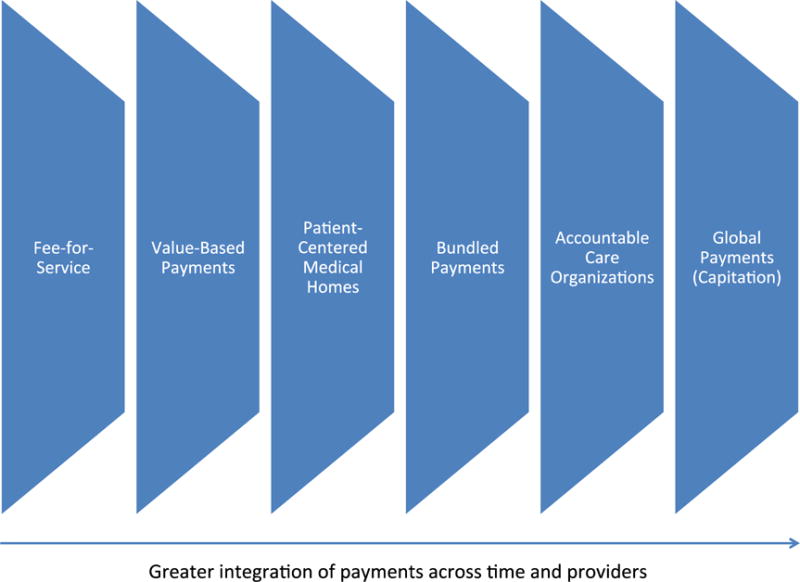

Bundled payments are a middle ground in the spectrum of health care payment models (Figure). On the one hand, they are a considerable shift from the traditional fee-for-service model, where providers are reimbursed separately for each distinct service provided. Yet importantly, bundled payments are not representative of global payments, or “capitation,” where a health care system is paid a lump-sum payment per attributed patient over a distinct time period, regardless of the number of distinct episodes of care. Additionally, global payments are intended to encompass care across multiple conditions that a patient may require while each individual episode of care is distinct and reimbursed separately in a bundled payment model. There are other alternative payment and delivery system reforms that fit between the extremes of fee-for-service and global payments on the spectrum of health care payment. These include value-based payments, where health systems or providers are given additional payments for high-quality care or levied financial penalties for poor quality care, and accountable care organizations where certain services or conditions may be covered in a capitated model, but other ancillary services may still be provided under fee-for-service.

Figure 1.

Spectrum of Health Care Payment Models and Delivery System Reforms Bundled payments represent a middle ground in between current fee-for-service model and global payments, or capitation.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Bundled Payments

There are many possible advantages of bundled payments over alternative payment models (Table 1). First, a lump-sum payment has the potential to discourage unnecessary care.5 In the traditional fee-for-service model, additional care translates to additional revenue, so physicians have little financial incentive to reduce unnecessary tests. Also, in the current fee-for-service model, there is no financial incentive to avoid complications or readmissions. In fact, hospitals with high complication rates historically have collected higher Medicare payments than hospitals with low complication rates.6 At the other extreme, bundled payments also have advantages over global payments given that there is no constraint on the number of episodes that can be reimbursed. For example, there is a strong disincentive in traditional capitation to care for patients with severe congestive heart failure who may require frequent hospitalizations. Health care systems received the same annual payment for that patient regardless of the number of hospitalizations they suffer in a year. In bundled payment agreements, the incentive to avoid these patients is mitigated, as each individual episode of care would be reimbursed. Finally, by introducing a single bundled cost, bundled payments also increase transparency and predictability of costs for patients and payers. Patients and payers may prefer this method of reimbursement, and thus hospitals that enter into bundled payment agreements may also benefit from expanded referral bases and increased market share due to preferred agreements.

Table 1.

Potential Advantages and Disadvantages of Bundled Payments

| Potential Advantages | Affected Party |

|---|---|

| Decrease health care costs | Payers |

| Improve care coordination | Patients |

| Discourage unnecessary care | Payers, Patients |

| Strong incentive to avoid complications and readmissions | Payers, Patients |

| No incentive to withhold necessary episodes of care (i.e., no constraint on number of episodes to be reimbursed, unlike global payments) | Providers, Patients |

| Increase transparency for costs of care | Payers, Patients |

| Expanded referral base and increased market share due to preferred agreements | Providers |

| Potential Disadvantages | |

| Difficulty defining discrete episodes of care for chronic conditions | Providers |

| Potential avoidance of necessary specialty care | Providers, Patients |

| May encourage unnecessary episodes of care | Payers, Patients |

| Many ways to “game” the system remain | Payers |

| Unclear accounting for value of academic endeavors (teaching, research) | Providers |

| Implementation challenges | Payers, Providers |

There are also potential disadvantages to moving from the current fee-for-service model towards bundled payments and these may affect stakeholders differently (Table 1). First, bundled payments are better suited for surgical procedures like coronary artery bypass grafting, in which there is a discrete beginning and end of an episode. However, the boundaries of where one episode ends and another begins are less clear for some chronic medical conditions, such as congestive heart failure. Second, though bundled payments may discourage unnecessary care, it is possible that the pendulum may swing too far in the opposite direction with their use. With bundled payments, health care systems may limit access to consultants or necessary services may be denied to patients for the sake of additional savings. Third, bundled payments do not discourage unnecessary episodes of care and patients would still be at risk for unwarranted hospitalizations and procedures as these would still be covered under this model.5

Other potential disadvantages to bundled payments are related to care of complex patients, many of whom are cared for at academic centers. Under any reimbursement model, there are always ways to “game” the system, and bundled payments are no different.7 Health care systems may still avoid “sick” patients in situations where they anticipate the bundled payment may not cover the expected health care costs or patients may also be “up-coded” to draw larger reimbursement. Another related concern is that providers may avoid coding complications of care that may require increased health care costs until the defined time period covered by a bundled payment agreement has expired (e.g. waiting to diagnose a sacral decubitus ulcer on postoperative day 31 when the bundled payment agreement covers care up until post-operative day 30). Finally, it also is possible that academic health centers may be disadvantaged by bundled payments. In addition to patient care, these centers prioritize research and teaching. Without consideration of this and special payments or other allowances to address this, academic centers may be negatively impacted by bundled payment agreements.

It is also important to consider major challenges in the implementation of bundled payments. In theory, there may be large savings with bundled payments, however, the details of how bundled payments will be executed must be carefully considered. Transitioning from the current payment paradigm will require significant activation energy. Engagement and agreement of all involved stakeholders may be difficult. There may be large administrative costs to determine target prices, and determination of which conditions to include may be fraught with challenges. Additionally, there will be challenges in getting physicians across multiple disciplines, hospitals, and other non-physician providers to mutually agree on distributing appropriate portions of the payment pie in an equitable manner.

Historical Development and Early Evidence

The very first step towards bundled payments was the development of Medicare’s Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) in the 1980s, which introduced Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) payments. DRG payments fundamentally changed how hospitals were reimbursed. Prior to 1983, hospitals were reimbursed retrospectively based on hospital costs incurred during a patient’s hospital stay along the fee-for-service model. With DRG payments, which are adjusted based on a patient’s diagnosis and comorbidities, hospitals were given a single prospective per-discharge payment that bundled all of a facility’s costs, including room and board, nursing, and costs associated with specialized care and ancillary services. Though hospital payments could be additionally adjusted by many other factors (e.g., teaching status, Disproportionate Share Hospital status, etc.), a large proportion of inpatient hospital care was now paid through one bundled payment. Other payers adopted a similar payment policy shortly thereafter and DRG payments are now the standard for facility payments for inpatient care. Implementation of the IPPS led to a slowing in the increase of Medicare spending.8–10 Hospital resource utilization, including length of stay also decreased following implementation of the IPPS.11 However, the measured quality of inpatient care was not changed; mortality and readmission rates remained either the same or decreased after implementation of the IPPS.9 Although the IPPS was a large step in bundling of medical services, it only focused on inpatient services. Payments for physicians, post-acute care, and readmissions were not included in this plan. While the IPPS was being implemented, there were rapid increases in the prevalence of outpatient surgery and the utilization of home health services.11 Additionally, outpatient hospital and post-acute care payments (services not bundled in the IPPS) grew with the implementation of the IPPS.11 Thus, the overall effect of the IPPS may be difficult to interpret, as the reduction in inpatient spending was accompanied by a shift and growth in outpatient care.

Cardiovascular conditions have played a special role in the genesis and development of bundled payments beyond inpatient hospital charges (Table 2). In 1984, soon after the introduction of the IPPS, the Texas Heart Institute developed CardioVascular Care Providers, Inc., bundling hospital and physician charges together for cardiovascular surgery.12 The plan was initially offered in 1984 to non-Medicare (<65-year-old) patients and was extended to Medicare patients who required coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in 1993. Detailed evaluations of the program have been limited, though the authors from the institution have claimed the plan was beneficial for patients, physicians, and providers.12 Patients received high-quality medical care with little or no out-of-pocket expense as well as increased access to care by decreasing the costs of medical care. Physicians were able to establish and expand patient referral bases and reduce overhead expenses due to streamlined billing processes. Payers experienced large savings for cardiovascular care and were better able to forecast costs for cardiovascular care.12

Table 2.

Current and Previous Bundled Payment Demonstrations

| Demonstration | Dates | Site | Enrollees | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CardioVascular Care Providers, Inc. | 1984 – present | Texas Heart Institute | Initially non-Medicare patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery, later expanded to all patients in 1993 | Payers experienced savings for cardiovascular care while providers were able to establish and expand patient referral bases. Patients benefited from high-quality medical care with little to no out-of-pocket expenses. Study limited to a single-center retrospective analysis |

| Medicare Participating Heart Bypass Center Demonstration | 1991 – 1996 | 7 Hospitals: 1. Saint Joseph’s Hospital, Atlanta, GA - 1991 2. St. Joseph Mercy Hospital, Ann Arbor, MI - 1991 3. The Ohio State University Hospitals, Columbus, OH – 1991 4. University Hospital, Boston, MA – 1991 5. St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital, Houston, TX – 1993 6. St. Vincent’s Hospital, Portland, OR – 1993 7. Methodist Hospital, Indianapolis, IN - 1993 |

Medicare patients undergoing CABG | Medicare spending in participating hospitals decreased by 10% over the 5 years of the demonstration. Three out of four hospitals decreased costs. Quality of care was maintained based on outcome measures. However, multiple challenges identified including large administrative burden to implementation and difficulty coordinating revenue sharing between hospitals and physicians |

| ProvenCare(SM) | 2006 – present | Geisinger Health Plan | At first, patients undergoing elective CABG Program has since expanded to multiple conditions including hip replacement, cataract surgery, PCI, bariatric surgery, and perinatal care |

Bundled payments implemented in coordination with evidence-based pay-for-performance program. Hospital charges decreased 5%. Adherence to evidence-based process measures increased from 59% to 100%. No changes in outcome measures. Study performed at highly-integrated healthcare delivery system with no control group. Results may not be generalizable to other healthcare settings. |

| Medicare Acute Care Episode (ACE) Demonstration | 2009 – 2012 | 5 Hospitals: 1. Hillcrest Medical Center, Tulsa, OK 2. Baptist Health System, San Antonio, TX 3. Oklahoma Heart Hospital, Oklahoma City, OK 4. Lovelace Health System, Albuquerque, NM 5. Exempla Saint Joseph Hospital, Denver, CO |

Medicare patients undergoing cardiovascular procedures and orthopedic joint replacements | Modest savings ($585) per episode for Medicare Part A and B expected payments. However, payments for post-acute care services (which are not included in bundled payment) increased, resulting in a net $319 in savings per episode. The largest savings were for orthopedic procedures. No aggregate effects on quality of care or patient outcomes. |

| PROMETHEUS Payment Model | 2006 – present | 3 initial sites: 1. Crozer Keyston Health System – Independence Blue Cross, PA 2. Employer’s Coalition on Health, Rockford, IL 3. Priority Health – Spectrum Health, Michigan Later, expanded to multiple other regional sites |

Patients being treated for one of 21 defined bundles ranging from chronic or acute medical conditions and procedures | Bundled payments implemented in coordination with pay-for-performance program and with allowance for care of complications. Initially, pilot sites encountered many difficulties executing bundled payment contracts citing multiple implementation challenges with bundle definitions, implementing quality measurement, determining accountability, and engaging providers More recently, PROMETHEUS payment pilots have been initiated multiple regional pilots with evaluations ongoing |

| Bundled Payments for Care Improvement | 2012 – present | National pilot program | Medicare patients treated for one of 48 eligible clinical conditions | Results are pending. |

In 1991, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) – now the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) – initiated the Medicare Participating Heart Bypass Center Demonstration.13 The demonstration was initially implemented in four hospitals, then expanded to include three additional hospitals in 1993, until the program’s termination in 1996. Medicare paid each of the participating hospitals a bundled payment for CABG. This bundled payment was meant to cover all inpatient and physician services as well as any costs related to readmissions. Hospitals and physicians were free to divide up the bundled payment any way they chose. Additionally, all participating hospitals were able to enter into private managed care contracts employing bundled payments for cardiac surgery.

To evaluate the demonstration, researchers compared participating hospitals with control hospitals from the same markets that were reimbursed in the traditional DRG per-case basis and where physicians were reimbursed using the fee-for-service model. Medicare spending in participating hospitals decreased by 10% over the 5 years of the demonstration.14 Eighty-six percent of the decrease was due to savings from bundled payments directly with 5% of the decrease related to lower post-discharge care expenses which were not bundled. Nine percent of savings were derived from shifts in market share from higher-cost non-demonstration hospitals to lower-cost demonstration hospitals. In terms of hospital costs derived from detailed hospital micro-cost information on each patient, three of the four original demonstration hospitals decreased costs between 18–40%. One hospital experienced increases in costs of 10–24% for the two DRGs covered under the demonstration, but for unclear reasons.

Of the four original demonstration hospitals, two facilities experiences significantly increased margins while the other two experienced a decrease, though the margins remained positive overall for all four facilities. In terms of physician payments, four major specialties all received fixed bundled payments regardless of services provided to different patients: the surgeon, the anesthesiologist, the cardiologist, and the radiologist. Other consulting physicians were paid their usual allowable Medicare fees out of designated funds that were a percentage holdback from these four specialties.

Examination of non-economic outcomes was less clear. There was a small, but significant, increase in the rate of complications for demonstration hospitals over the course of the demonstration. However, despite this increase in complications, mortality decreased significantly over the time course of the demonstration.14

There also were challenges to the demonstration identified using direct feedback from hospital managers, nurses, and physicians.14 Some consultants felt the quality of care was being compromised due to cutting back of consultant services. Additionally, most sites reported that they significantly underestimated the administrative burden required to implement the bundled payment system, including coordinating the revenue sharing between hospitals and physicians. Overall, results of the demonstration were mixed. Some hospitals were more successful than others. Hospital staff stated that aligning surgeon and hospital incentives to reduce costs was absolutely critical in changing practice patterns and improving department efficiency.

More Recent Bundled Payment Initiatives

Bundled payments have also been implemented with private insurers (Table 2). In 2006, the Geisinger Health Plan, a large non-profit integrated delivery system in Pennsylvania, implemented ProvenCare(SM).15 At the time, Geisinger had approximately 210,000 members in a total service area population of roughly 2.6 million. ProvenCare(SM) was implemented in three facilities for elective CABG and included a bundled payment for CABG that included preoperative evaluation and workup, all hospital and physician fees, post-acute care including cardiac rehabilitation, care for post-operative complications and readmissions within 90 days from surgery. The bundled payment was implemented in conjunction with an evidence-based, pay-for-performance program, which included introduction of 40 “best practice” components adopted from 20 clinical practice guidelines. The program attracted national attention in popular media and an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.16–18

Retrospective observational analysis of Geisinger’s three tertiary/quaternary medical centers compared 137 patients who underwent elective CABG in the year before implementation of ProvenCare(SM) to 117 patients who underwent elective CABG after implementation of the program.15 Hospital charges were found to decrease 5% among ProvenCare(SM) patients. There were no changes in post-operative length of stay, and modest, non-significant reductions in total length of stay (6.3 days before vs. 5.3 days after) and in 30-day readmissions (7.1% before vs. 6.0% after). Additionally, significantly more patients were discharged to home following surgery (81.0% before vs. 90.6% after, p<0.05). Importantly, adherence to the 40 “best practice” components increased from 59% to 100% following implementation of the program (p=0.001). This did not translate to any statistically significant changes in health outcomes (mortality, readmissions, complications), although the study had limited statistical power in this regard due to the sample size of the study. Importantly, it was reported that purchasers were highly receptive to bundled payments for CABG, citing a high valuation of financial predictability and aversion to open-ended risk and high-costs of postoperative complications and treatment failures.15

There were several limitations to this evaluation and its relevance for bundled payments. At the time of implementation, the Geisinger Health Plan was already a high-functioning, integrated healthcare delivery system with an electronic health record. This suggests that the health care system had both the resources to implement the program and perhaps more of a limited opportunity to demonstrate improvement. Additionally, the success behind ProvenCare may lie in the fact that Geisinger Health Plan functions as both a payer and an integrated provider system, allowing for easier alignment of incentives among the payer, hospitals, physicians, and post-acute care facilities. The program may have not led to the same successes in other health care settings. Further, ProvenCare was only applied to elective CABGs. Though ProvenCare was applied to 117 elective CABG patients over a 1-year period, in the same time period, there were an additional 290 non-elective CABGs performed that were excluded from the ProvenCare program.15 This limits the generalizability of their results. Applying the same program to other types of patients or other delivery models of care may not yield similar results. Additionally, the analysis did not have a control group of hospitals, thus it is difficult to discern whether the improvements seen in the program were an independent effect due to implementation of ProvenCare(SM), or whether there were existing secular trends. Finally, the bundled payment in ProvenCare(SM) was implemented concurrently with a pay-for-performance package. It is impossible to discern whether improvements were due to the bundled payments, the financial incentive to implement evidence-based practices, or the combination of the two together. Nonetheless, this pilot program demonstrated the possibility of decreased health care costs and resource utilization while simultaneously maintaining or improving the quality of care provided in a large health care system. The program has since expanded to percutaneous coronary intervention, bariatric surgery, and perinatal care.19

There are currently other bundled payment programs in progress (Table 2). In 2009, Medicare initiated another demonstration of bundled payments: the Medicare Acute Care Episode (ACE) Demonstration.20 The demonstration seeks to implement bundled payments for orthopedic joint replacements and cardiovascular procedures (CABG, valve replacement, pacemaker and defibrillator procedures, and angioplasty). The program provided a lump-sum payment for hospital and physician services accrued during an inpatient stay in five demonstration hospitals. Importantly, post-acute care services were not included in the demonstration. Initial results report modest savings with no appreciable differences in quality of care.21 Analysis comparing ACE demonstration hospitals with non-participating hospitals revealed an average savings of $585 per episode from combined Medicare Part A and B expected payments (facility and physician payments). However, payments for post-acute care services (which were not included in the bundle payment) increased. Therefore, the per-episode net savings was $319, for a total net savings of approximately $4 million across 12,501 cardiovascular and orthopedic procedures. The largest savings were for orthopedic procedures, while the smallest savings per episode was for PCI procedures ($71). Evaluation of 22 quality of care, resource utilization, and case mix measures did not reveal any aggregate effect.21 As a result of the modest success of the demonstration, some proponents have suggested expanding the program with inclusion of post-acute care services.22 Additionally, because hospitals were more successful in achieving savings for orthopedic procedures than for cardiac procedures, additional work may focus solely on the types of procedures that may benefit the most from this payment model.

In 2006, with funding from the Commonwealth Fund and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the PROMETHEUS (Provider Payment Reform for Outcomes, Margins, Evidence, Transparency, Hassle-reduction, Excellence, Understandability, and Sustainability) Payment model was initiated.23 The model, managed by the Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute (HCI3) seeks to develop a single bundled payment for all services related to care of a single condition based on “Evidence-informed Case Rates” (ECRs). PROMETHEUS Payment has developed ECRs, adjusted for patient severity and complexity for multiple acute, chronic, and inpatient conditions and procedures including acute myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure.24 Additionally, there is a pay-for-performance aspect to the program, with incentive payments for meeting specific quality metrics including provider collaboration. Also, there is an allowance calculated in the ECR for care of complications. This allowance for potentially avoidable complications is paid out either to cover the costs of caring for complications, or as a bonus to providers if complications are avoided. Thus, the largest profit margins exist for health care systems that provide high-quality care with low incidence of complications.

Multiple implementation challenges have been identified with PROMETHEUS Payment. The bundled payment model was initially piloted at few sites. However, these pilot sites had many difficulties executing bundled payment contracts between payers and providers.25 Other challenges include defining a specific “bundle,” defining the payment method, implementing quality measurement, determining accountability, engaging providers, and delivery redesign. More recently, spurred by renewed interest in bundled payments due to the Affordable Care Act, many regional pilot programs have initiated PROMETHEUS payments for a variety of conditions.26, 27 Further evaluations of the PROMETHEUS Payment Model in pilot programs are still ongoing, however HCI3 has identified full CEO engagement, commitment by payer and provider, clean and complete claims and eligibility data, electronic medical record systems, and a sense of urgency to achieve progress as “key ingredients” necessary for even beginning the process of implementation.

Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement

Perhaps the largest and most relevant ongoing program for providers is Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI), a program developed by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, which was created by the Affordable Care Act to test innovative payment and service delivery models.28 The program accepted applications from hospitals and other providers for the initiative in 2012. The initiative offered four different payment models that varied the type of services to be bundled together. Model 1 includes payments for the index hospitalization only; Model 2 is the most all-encompassing, bundling all services around an index hospitalization, including readmissions, physician services, and post-acute care; Model 3 includes only post-acute care payments; Model 4 includes facility and physician claims for the index hospitalization and readmissions paid prospectively. Model 2 is the most popular model to date, with participants selecting which services to include from up to 48 conditions, 15 of which are cardiovascular (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cardiovascular conditions included in Medicare’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement

| Condition |

|---|

| Stroke |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention |

| Pacemaker implant |

| Cardiac defibrillator implant |

| Pacemaker replacement or revision |

| Automatic implantable cardiac defibrillator generator or lead placement |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Acute myocardial infarction |

| Cardiac arrhythmia |

| Cardiac valve procedures |

| Other vascular surgery |

| Other major cardiovascular procedures |

| Medical peripheral vascular disorders |

| Atherosclerosis |

Although still underway, preliminary analysis of the demonstration has identified significant barriers to the program with most of the key results pending.29 Thus far, what we do know is that few hospitals have enrolled in BPCI (<5% of eligible acute care hospitals). Participating hospitals were more likely to be teaching hospitals, non-profit hospitals, and large hospitals. They were also more likely to be located in the Northeast. More than half of hospitals that chose to enroll in Model 2 of the BPCI also limited their participation to only one or two conditions out of the 48 eligible with lower extremity joint replacement the most common condition chosen, followed by many cardiac conditions including congestive heart failure, CABG, and acute myocardial infarction. Hospitals tended to choose conditions for which post-acute care and readmissions contributed a large portion to spending.

Summary of the Evidence Thus Far

Bundled payments initiatives thus far have demonstrated modest potential to curb health care costs without decreasing health care quality, and potentially even improving it. With varying degrees of success, previous demonstrations such as the Medicare Participating Heart Bypass Demonstration and Geisinger’s ProvenCare have shown savings for payers but these have been modest overall. Evidence regarding the quality of care has not demonstrated worsening care, and in fact, has shown improved performance in quality measures in some arenas. The example of Geisinger’s ProvenCare, where bundled payments were tied to pay-for-performance initiatives, is one example of improved quality measures. However, the evidence around the impact of bundled payments remains surprisingly limited. Few rigorous evaluations of bundled payment programs have been published, and those that have been published are retrospective analyses with limited control groups for comparison.

While evidence around the effects of bundled payments on outcomes remains limited, a recurring theme in bundled payment initiatives has been the challenges in program implementation. Recent attempts at implementing bundled payments for orthopedic conditions in California failed, due to administrative burden, state regulatory uncertainty, and disagreements about bundled definition and assumption of risk.30 Context and local environment have affected the success of many bundled payment programs. Geisinger’s ProvenCare may have achieved success due to the streamlined, integrated design of its unique health care system. Alignment of incentives may have been easier to achieve since Geisinger Health Plan is both the payer and provider. In contrast, the Medicare Participating Heart Bypass Demonstration highlighted the administrative challenges to implementation. Furthermore, the initial pilot sites for PROMETHEUS Payment Models have encountered multiple obstacles due to sorting the complex details associated with implementation. There may be significant differences in the readiness and capability of different hospitals and hospital systems to participate in bundling due to differences in integration and administrative leadership across the country.

Implications and Future Directions

Given this mixed picture of the evidence, it is important to place bundled payments in an appropriate context. On one hand, the future of bundled payments remains largely uncertain. The broader picture of healthcare payment reform following the Affordable Care Act has left many health care systems preparing for the possibility of numerous different and complex policy initiatives, including accountable care organizations, pay-for-performance and value based purchasing programs, and patient centered medical homes. Stakeholders may be hesitant to invest in bundled payments unless they are perceived to be a major initiative within the changing policy landscape. Also, it is clear that challenges to their implementation have not been adequately addressed in key circumstances. Even after the success of the Medicare Participating Heart Bypass Demonstration in the 1990s, for example, bundled payments did not receive greater attention until a decade later with Geisinger’s ProvenCare program.

However, it also is possible that big changes in the current health care landscape may be what ultimately push health care systems and payers toward bundled payment programs. The shift to electronic health records will allow for easier cooperation and coordination of care, streamlining the development of these programs across multiple providers. Another prevailing trend in cardiovascular care that may facilitate the implementation of bundled payments is the increasing merger of private physician groups into integrated hospital-physician practices. This will have effects for both accountable care organizations and bundled payment agreements. Additionally, the shift away from traditional academic departments into service lines and “heart teams,” integrating cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and anesthesiologists (as well as others) may facilitate the adoption of bundled payments. With improved collaboration from individuals traditionally separated in academic silos, the feasibility and ease of bundled payments may also improve. The introduction of transcatheter aortic valve replacement serves as a prominent example of improved cooperation among disparate medical providers.

If the implementation challenges highlighted in previous demonstrations can be overcome, bundled payments could significantly change patterns of care delivery for cardiovascular patients. Though bundled payment programs have been initiated for many different cardiovascular conditions, bundled payments have the potential for greatest savings for higher cost patients that require more coordination of care, such as those undergoing major procedures or with congestive heart failure and frequent annual hospitalizations.

Nevertheless, the future success (or lack thereof) of bundled payments will hinge on further rigorous evaluation of current ongoing pilot demonstrations. Thus far, cardiovascular procedures have been the focal point of many bundled payment projects. Whether the findings of these pilot projects can be generalizable to other cardiovascular conditions is unknown. Previous demonstrations have shown the potential for health care savings and improved quality, but they have also highlighted the challenges of implementation. Some of these implementation challenges may abate with time, and if they do, bundled payments are likely to play a growing role in the evolving landscape of health care payment reform.

Acknowledgments

Terry Shih is supported by grant from the National Institutes of Health (5T32HL07612309). Lena Chen is supported by a Career Development Grant Award (K08HS020671) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. This project is also supported by funding from the National Institute of Aging (Grant No. P01AG019783). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Government.

Footnotes

Journal Subject Codes: [100] Health policy and Outcomes Research

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller DC, Gust C, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer N, Skinner J, Birkmeyer JD. Large variations in medicare payments for surgery highlight savings potential from bundled payment programs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:2107–2115. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandra A, Dalton MA, Holmes J. Large increases in spending on postacute care in medicare point to the potential for cost savings in these settings. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:864–872. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mechanic R. Post-acute care–the next frontier for controlling medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:692–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller HD. From volume to value: Better ways to pay for health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:1418–1428. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eappen S, Lane BH, Rosenberg B, Lipsitz SA, Sadoff D, Matheson D, Berry WR, Lester M, Gawande AA. Relationship between occurrence of surgical complications and hospital finances. JAMA. 2013;309:1599–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Reforming the delivery system. 2008 Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/Jun08_EntireReport.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 8.Chulis GS. Assessing medicare’s prospective payment system for hospitals. Med Care Rev. 1991;48:167–206. doi: 10.1177/002570879104800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lave JR. The effect of the medicare prospective payment system. Ann Rev Pub Health. 1989;10:141–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.10.050189.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White C. Why did medicare spending growth slow down? Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:793–802. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feinglass J, Holloway JJ. The initial impact of the medicare prospective payment system on u.S. Health care: A review of the literature. Med Care Rev. 1991;48:91–115. doi: 10.1177/002570879104800104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edmonds C, Hallman GL. Cardiovascular care providers. A pioneer in bundled services, shared risk, and single payment. Tex Heart Inst J. 1995;22:72–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cromwell J, Dayhoff DA, Thoumaian AH. Cost savings and physician responses to global bundled payments for medicare heart bypass surgery. Health Care Financ Rev. 1997;19:41–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cromwell J, Dayhoff DA, McCall NT, Subramanian S, Freitas RC, Hart RJ, Caswell C, Stason W. Medicare Participating Heart Bypass Demonstration. Executive Summary. Final report. 1998 http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Demonstration-Projects/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/downloads/Medicare_Heart_Bypass_Executive_Summary.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 15.Casale AS, Paulus RA, Selna MJ, Doll MC, Bothe AE, Jr, McKinley KE, Berry SA, Davis DE, Gilfillan RJ, Hamory BH, Steele GD., Jr “ProvenCareSM”: A provider-driven pay-for-performance program for acute episodic cardiac surgical care. Ann Surg. 2007;246:613–621. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a996. discussion 621–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abelson R. In bid for better care, surgery with a warranty. New York Times. 2007 http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/17/business/17quality.html?_r=2&. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 17.Abrams L. Where surgery comes with a 90-day guarantee. The Atlantic. 2012 http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2012/09/where-surgery-comes-with-a-90-day-guarantee/262841/. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 18.Lee TH. Pay for performance, version 2.0? N Engl J Med. 2007;357:531–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geisinger. ProvenCare Portfolio. http://www.geisinger.org/provencare/portfolio.html. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Acute Care Episode Demonstration for orthopedic and cardiovascular surgery. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Demonstration-Projects/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/downloads/ACE_web_page.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 21.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Servces. Evaluation of the Medicare Acute Care Episode (ACE) demonstration. 2013 http://downloads.cms.gov/files/cmmi/ACE-EvaluationReport-Final-5-2-14.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 22.Calsyn M, Emanuel EJ. Controlling costs by expanding the medicare acute care episode demonstration. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1438–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Brantes F, Rosenthal MB, Painter M. Building a bridge from fragmentation to accountability–the prometheus payment model. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1033–1036. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0906121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.PROMETHEUS payment: On the frontlines of health care payment reform. 2010 http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2010/rwjf63464. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 25.Hussey PS, Ridgely MS, Rosenthal MB. The PROMETHEUS bundled payment experiment: Slow start shows problems in implementing new payment models. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:2116–2124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute. PROMETHEUS in time: Current status of implementations and analytic activities around the nation. http://www.hci3.org/content/prometheus-time-current-status-implementations-and-analytic-activities-around-nation. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 27.Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute. The progression of PROMETHEUS payment. http://www.hci3.org/sites/default/files/files/ThatWasThenThisIsNow-2011-11-10.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 28.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General information. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/. Accessed July 30, 2014.

- 29.Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Opportunities for savings in the bundled payments for care improvement initiative; Academy Health Annual Research Meeting; San Diego. June 9, 2014; http://www.academyhealth.org/files/2014/monday/tsai2.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridgely MS, de Vries D, Bozic KJ, Hussey PS. Bundled payment fails to gain a foothold in california: The experience of the IHA bundled payment demonstration. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1345–1352. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]