Abstract

Atrazine is an herbicide applied to agricultural crops and is indicated to be an endocrine disruptor. Atrazine is frequently found to contaminate potable water supplies above the maximum contaminant level of 3 µg/L as defined by the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency. The developmental origin of adult disease hypothesis suggests that toxicant exposure during development can increase the risk of certain diseases during adulthood. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying disease progression are still unknown. In this study, zebrafish embryos were exposed to 0, 0.3, 3, or 30 µg/L atrazine throughout embryogenesis. Larvae were then allowed to mature under normal laboratory conditions with no further chemical treatment until 7 days post fertilization (dpf) or adulthood and neurotransmitter analysis completed. No significant alterations in neurotransmitter levels was observed at 7 dpf or in adult males, but a significant decrease in 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) and serotonin turnover was seen in adult female brain tissue. Transcriptomic analysis was completed on adult female brain tissue to identify molecular pathways underlying the observed neurological alterations. Altered expression of 1853, 84, and 419 genes in the females exposed to 0.3, 3, or 30 µg/L atrazine during embryogenesis were identified, respectively. There was a high level of overlap between the biological processes and molecular pathways in which the altered genes were associated. Moreover, a subset of genes was down regulated throughout the serotonergic pathway. These results provide support of the developmental origins of neurological alterations observed in adult female zebrafish exposed to atrazine during embryogenesis.

Keywords: atrazine, development, developmental origins of health and disease, neurotransmitters, transcriptomics, zebrafish

1.0 INTRODUCTION

During embryonic development, organisms exhibit a high level of developmental plasticity allowing for alterations of the genetic landscape in response to the surrounding environment which can ultimately result in a broad range of adult phenotypes (Feuer et al. 2014). It is within these genetic and epigenetic alterations that an increased risk of developing diseases in adulthood occurs. This concept is commonly referred to as the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis. The DOHaD hypothesis came into view during the late 1980’s based upon a series of epidemiological studies which found an association between a reduction in fetal growth and the development of cardiovascular and metabolic disease in later life by Barker and colleges (Barker and Osmond, 1986; Barker et al. 1993). As research progressed, the number of diseases linked to a developmental origin has increased to include cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and obesity (Dolinoy and Jirtle, 2008). The understanding of the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms behind the development of these diseases is still under investigation. Also, it is within this developmental plasticity that increases the vulnerability of developing organisms to toxicant exposure such as endocrine disrupting chemicals.

Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are a group of chemicals that are diverse in structure. EDCs are found in many products such as plasticizers, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and personal care products and can therefore result in exposures in diverse populations (Diamanti-Kandarakis et al. 2009). Since exposure to EDCs encompasses a broad spectrum of the population, public concern focused on investigating the harmful effects of EDCs and their mechanisms of toxicity has increased. EDCs pose significant harm to human health due to their ability to disrupt multiple processes including mimicry of endogenous hormones, alterations of hormone homeostasis, and disruption of hormone synthesis, transport, and metabolism (Diamanti-Kandarakis et al. 2009). Evidence suggests that EDCs do not adhere to classic dose-response toxicological principles; rather they are part of the 'low dose hypothesis' due to their ability to disrupt hormonal homeostasis at low levels and do not always follow a dose response (Diamanti-Kandarakis et al. 2009). Concern about the effects of EDCs during vulnerable developmental periods and childhood has been investigated in animal model systems (Belloni et al. 2011; Davis et al. 2011; Weber et al. 2013) and literature examining the lasting effects of a developmental exposure to EDCs and their contribution to the development of adult disease is under investigation (Birnbaum and Fenton, 2003; Ma et al. 2010).

Atrazine (ATZ) (2-chloro-4-ethylamino-6-isopropylamino-1,3,5-triazine) is a common pre-emergent agricultural herbicide that is a reported endocrine disruptor and is indicated to be a potential carcinogen (Cooper et al. 2000; Freeman and Rayburn, 2005; Freeman et al. 2011; Wetzel et al. 1994). Atrazine has widespread use in the Midwest United States and is used to prevent broad leaf and grassy weeds in corn, sorghum grass, sugar cane, and wheat crops. Atrazine is commonly applied in the spring and summer months and has been shown to contaminate potable water supplies; often above the maximum contaminant level (MCL) set by the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of 3 µg/L (Ochoa-Acuña et al. 2009; Rohr and McCoy, 2010; U.S. EPA. 2002). Due to the persistence and mobility of atrazine in the environment its use was banned in European countries in 2004 (Fakhouri et al. 2010).

The adverse endocrine effects of atrazine caused by acute and chronic exposures during adulthood have been examined. Studies have implicated that atrazine disrupts the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis by decreasing the pre-ovulatory surge of luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and prolactin (PRL) (Cooper et al. 2000; Foradori et al. 2009). Disruption of these hormones can lead to early reproductive senescence and dysfunction. Although these studies have shown the disruptive effects of atrazine on the endocrine system, they are representative of an exposure during adulthood. Understanding the effects of a developmental atrazine exposure and the later in life impact is of key importance. Literature noting the effects of a developmental atrazine exposure on the adult female and male reproductive system has shown a delay in mammary gland development and alterations in estrous cycles in female rodents (Davis et al. 2011; Rayner et al. 2005) and a delay in puberty and reduced testosterone levels (Fraites et al. 2011).

Although it is a well-regarded hypothesis that atrazine works by alterations throughout the HPG and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axes (Fraites et al. 2009), understanding its effects on the central nervous system (CNS) is necessary in elucidating its mechanism of action due to its ability to readily cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) (Ross et al. 2009). Multiple studies have started to examine the effects of atrazine on the dopaminergic system caused by developmental and adulthood exposures (Coban and Filipov, 2007; Lin et al. 2013a; Rodriguez et al. 2013). However, the effect of atrazine on other monoamine neurotransmitters such as serotonin (5-HT), as well as its effects on the GABAergic system is still under investigation (Das et al. 2000; Rajkovic et al. 2011).

There are considerable strengths in using the zebrafish model to define mechanisms associated with developmental toxicant exposure and the developmental origins of adult health and disease including ex utero fertilization and embryonic development, rapid embryogenesis, and a relatively short life span. Paired with these biological strengths are the structural and functional homology of the zebrafish CNS to humans and the conserved genetic, molecular, and endocrine pathways making the zebrafish a powerful model to assess the later life alterations caused by an embryonic atrazine exposure (de Esch et al. 2012; Howe et al. 2013). There are a few recent studies that are now utilizing the zebrafish to examine the contributions of toxicant exposure to the DOHaD hypothesis. These studies include the effects of embryonic methyl mercury (MeHg) (Xu et al. 2012), as well as TCDD (Barker et al. 2013). These studies provide valuable data and support of not only the DOHaD but also for utilizing the zebrafish as a primary model for investigation.

To begin to identify if an embryonic atrazine exposure may alter neurotransmitter profiles later in life, in this study zebrafish were exposed to 0, 0.3, 3 or 30 µg/L atrazine during embryogenesis. These concentrations of atrazine are likely found in the environment in which the general population is exposed including pregnant women, their fetuses, and young children, the primary demographic which the DOHaD hypothesis targets. Following the exposure period, zebrafish were rinsed and allowed to mature in clean water under normal laboratory conditions. Neurotransmitter levels were measured at 7 days post fertilization (dpf) and in mature adults (9 mpf) and then the transcriptomic profile of adult female brain tissue was defined to identify genetic mechanisms underlying observed neurological alterations.

2.0 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Zebrafish husbandry and atrazine exposure

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) wild-type AB strain were housed in Z-Hab systems (Aquatic Habitats, Apopka, FL) on a 14:10 hour light:dark cycle. Water quality was maintained at 28°C, pH of 7.0–7.2, and conductivity range of 470–550 µS. Adult fish were bred in cages and embryos were collected and staged following established protocols (Peterson et al. 2011; Westerfield 2007). A stock solution of technical grade atrazine (98.1% purity) (CAS 1912-24-9; Chem Service, West Chester, PA) at a concentration of 10 mg/L was prepared near the solubility limit in water as previously described (Weber et al. 2013). Embryos were dosed with 0 (aquaria water only), 0.3, 3, or 30 µg/L atrazine from 1–3 dpf as previously described (Weber et al. 2013). After the exposure, larvae were rinsed with clean fish system water, housed in 4-liter tanks in the zebrafish systems and allowed to mature under normal growing conditions until 6–9 mpf. All protocols were approved by Purdue University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (A3231-01) with all fish treated humanely and with regard for alleviation of suffering.

2.2 High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection in larvae and adult zebrafish

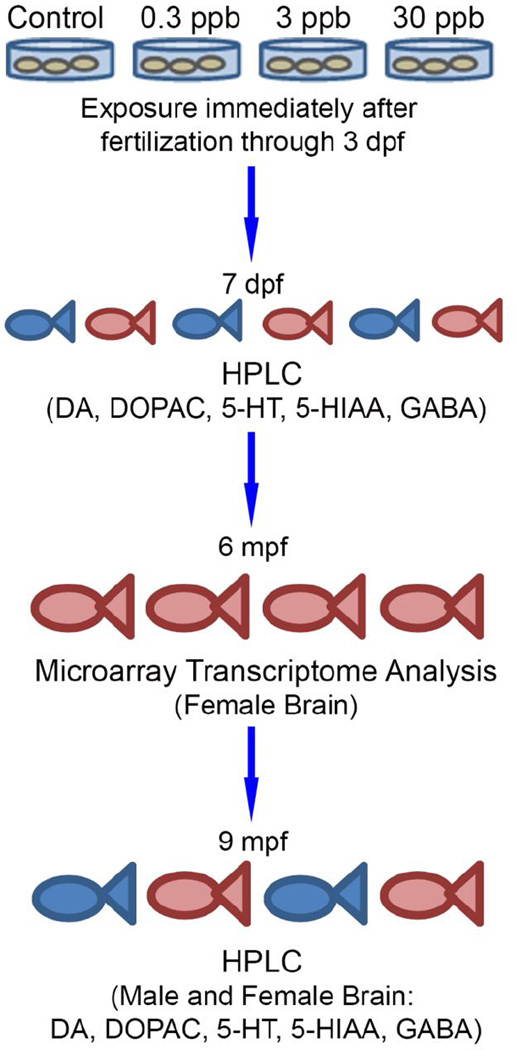

Neurotransmitter analysis on larvae and adult male and female brain tissue was conducted similar to previously reported (Wirbisky et al. 2014). For the neurotransmitter analysis at 7 dpf, 30 larvae per treatment were pooled for analysis (considered as one biological replicate) (Figure 1). For the adult neurotransmitter analysis, eight adult male and eight adult female zebrafish were collected from each treatment at 9 months post fertilization (mpf), anesthetized in MS-222 (4 mg/mL), and brain tissue dissected and submerged in 500 µL of 0.4M perchloric acid (HClO4). Samples were then sonicated (Power 40%, Pulse 2 seconds and stop for 1 second; Fisher Scientific, Model FB120, 120W) for 45 seconds per sample and centrifuged at 16,000 rcf for 35 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a 0.22 µM Spin-X tube (Bio-Rad) and centrifuged at 1,000 rcf for 15 minutes at 4°C. The lysate was stored at −80°C until HPLC analysis. For GABA detection, samples were combined with a derivatization agent (o-phthalaldehyde, methanol, and 2-mercaptoethanol) and injected at 4°C. The isocratic mobile phase consisted of disodium hydrogen phosphate anhydrous, water, 22% methanol, 3.5% acetonitrile, pH 6.75. Separation occurred at 40°C with a flow rate of 0.450 mL/min. The isocratic monoamine mobile phase (consisting of 0.08 M NaH2PO4, 10% methanol, 2% acetonitrile, 2.0 mM OSA, 0.025 mM EDTA, and 0.2 mM TEA, in 13 mΩ purified water, pH 2.4) was used for the detection of dopamine (DA), 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), serotonin (5-HT), and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA). Separation occurred at 32°C at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. HPLC analysis of DA, DOPAC, 5-HT, 5-HIAA, and GABA were analyzed on a Dionex UltiMate 3000 (ThermoScientific; Germering, Germany) system equipped with an autosampler and Coulochem III (ThermoScientific) electrochemical detector. The electrochemical potential of the detector was set at 550 and 250 mV for GABA and additional neurotransmitters, respectively with a conditioning cell at −150 mV. Samples were injected and separated on a reverse phase C18 column (150 × 3.2mm, 3.0 µm particle size, MD-150, Thermo Scientific, Bannockburn, IL). Neurotransmitter levels were quantified using a standard curve generated by high purity standards. Neurotransmitter amounts were reported as pg/zebrafish or pg/brain. Chromelon 7.0 software was used for data collection and analysis. Three biological replicates were completed (n=3) for larvae analysis. Eight biological replicates were completed (n=8) for adult brain tissue analysis with males and females analyzed separately. Neurotransmitter statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism6 statistical software. Data were analyzed for statistical differences with a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). A Tukeys post-hoc test was completed when a significant ANOVA was observed (α<0.05) to determine groups that were statistically different from each other.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the experimental design.

Following fertilization embryos were pooled to 50 embryos per sample and dosed with a control treatment or an atrazine treatment of 0.3, 3, or 30 ppb through 3 dpf. For larvae neurotransmitter analysis, embryos were dosed as described above and then allowed to grow under normal conditions until 7 dpf. 30 embryos were pooled per sample for analysis (considered as subsamples). Three biological replicates were included. For the adult microarray and neurotransmitter analysis, after the 3 dpf exposure period embryos were rinsed and allowed to mature under normal conditions until 5–6 or 9 mpf, respectively. Brain tissue was dissected and processed for microarray or HPLC analysis (n=3 for adult females for the microarray analysis and n=8 for the HPLC analysis in adult female and males).

2.3 Transcriptome microarray analysis of adult female brain tissue

Brains from three adult females (approximately 5–6 mpf), each from a different biological replicate (n = 3) were collected from each group exposed to an atrazine treatment (0, 0.3, 3, or 30 µg/L) during embryogenesis (1–3 dpf), homogenized in Trizol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated and converted to cDNA following established protocols (Peterson et al. 2011; Weber et al. 2013). Transcriptomic microarray analysis was conducted using the one-color hybridization strategy to compare gene expression profiles among the atrazine treatments with the zebrafish 12X135K expression platform (Roche NimbleGen, Madison, WI). This microarray is a multiplex format of 12 arrays each consisting of 135,000 60-mer probes interrogating 38,489 targets with three probes per target and is based on the Ensembl and UCSC Genome Databases. Following hybridization, arrays were washed and then scanned at 2 microns on a NimbleGen MS 200 Microarray Scanner (Roche NimbleGen, Madison, WI) at the Genomics and Bioinformatics Core Facility at Notre Dame University. Array image data was extracted using the NimbleScan software program (Roche NimbleGen, Madison, WI). Fluorescence signal intensities were normalized using quantile normalization (Bolstad et al. 2003) and gene calls generated using the Robust Multichip Average algorithm (Irizarry et al. 2003) following manufacturer recommendations. Array image data was analyzed as previously described (Freeman et al. 2014; Peterson et al. 2011; Weber et al. 2013). A robust and reproducible list of differentially expressed genes for each atrazine treatment using recommendations from the Microarray Quality Consortium (Guo et al. 2006; Shi et al. 2006) was first determined by genes consistently expressed using an ANOVA in SAS software (p<0.05) and substantially altered with a mean absolute log2 expression ratio of at least 0.585 (50% increase or decrease in expression). Each gene list was imported into Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) for gene ontology and molecular pathway analysis following similar parameters as described previously (Freeman et al. 2014; Peterson et al. 2011; Weber et al. 2013). Genes referred to in the results and discussion sections are represented as the human homologs of the genes identified to be altered by microarrays.

2.4 Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) confirmation of microarrays

qPCR was performed on a subset of selected genes altered in the gene expression array analysis (ABCD2, APLP2, RELN and PER3) using the BioRad iQ SYBR Green Supermix kit according to manufacturer’s recommendations. AVP was also assessed as a gene without significant expression alterations in the microarray experiment. Probes specific to target genes were designed using the Primer3 website (Table 1). qPCR was performed following similar methods as described previously (Freeman et al. 2014; Peterson et al. 2011; Weber et al. 2013) following MIQE guidelines (Bustin et al. 2009). Similar to as performed in previous studies in our laboratory (Peterson et al. 2011, 2013; Weber et al. 2013; Wirbisky et al. 2014), several genes were assessed to determine the best reference gene to be used for this data set (data not shown). β-actin was found to be the most consistent, not altered by atrazine exposure, and least variable for this analysis. qPCR was performed on the same samples as used in the microarray analysis. Experimental samples were run in triplicate (technical replicates) and gene expression was normalized to β-actin. Efficiency and specificity were checked with melting and dilution curve analysis and no-template controls. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS statistical software. Atrazine treatments and control treatment were analyzed for statistical differences with an ANOVA. A post-hoc least significant difference (LSD) test was completed when a significant ANOVA was observed (α<0.05).

Table 1.

Primers used in qPCR validation of microarray analysis.

| Seq ID | Gene Symbol |

Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| ENSDART00000082522 | ABCD2 | Forward: AACTGATGAAATGGCTCCTGAT Reverse: TCTGGTCGGTGAAGTAGGTCTT |

| BI672476 | APLP2 | Forward: CAAGTGACGTTCTTCTGGAGTG Reverse: TAGTCATCAGTCTGGTGCTGCT |

| ZV700S00003471 | RELN | Forward: TTCTACTGCCCCTACCAGAGAG Reverse: AATCTCGAGAAAACTCCAGACG |

| NM_131584 | PER3 | Forward: AATAGAGCCGAATGAGAAGCTG Reverse: TCTGTATCGGGTCTGTTTTCCT |

| NM_183346 | AVP | Forward: CCCATCAGACAGTGTATGTCGT Reverse: GACAGCTGCTCCTCTTCCAT |

| NM_181601 | β-ACTIN | Forward: CTAAAAACTGGAACGGTGAAGG Reverse: AGGCAAATAAGTTTCGGAACAA |

3.0 RESULTS

3.1 Neurotransmitter analysis of zebrafish larvae exposed to atrazine during embryogenesis

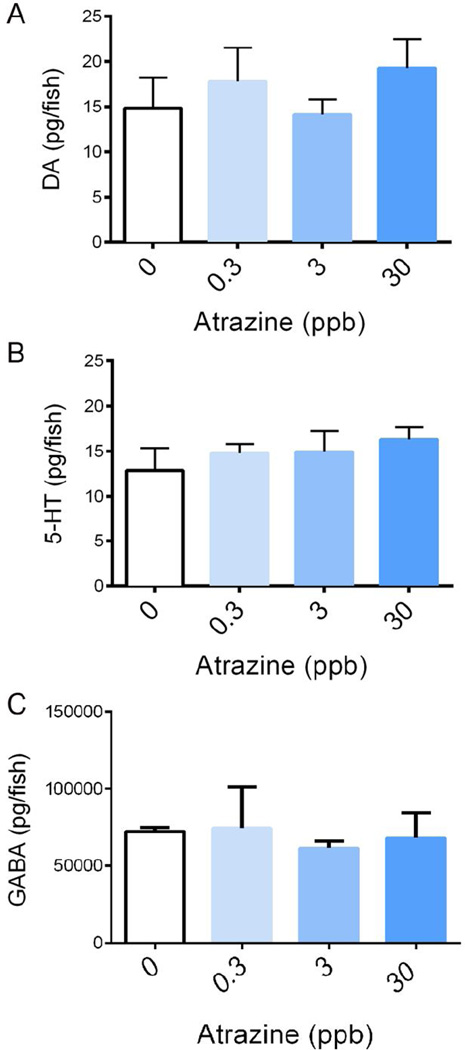

No statistical significance was found in any of the neurotransmitter levels at this developmental time point (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Neurotransmitter analysis of DA, 5-HT, and GABA in 7 dpf zebrafish larvae.

Zebrafish embryos were exposed to 0, 0.3, 3, or 30 ppb atrazine through embryogenesis. Following developmental exposure, embryos were allowed to mature under normal conditions until 7 dpf. No significant alterations occurred, as assessed by ANOVA in (A) DA (p=0.6297), (B) 5-HT (p=0.6601), or (C) GABA (p=0.7604) due to the embryonic atrazine exposure (n=3). Error bars indicate standard deviation.

3.2 Neurotransmitter analysis of dopamine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, and dopamine turnover in the adult female and male brain exposed to atrazine during embryogenesis

No statistical differences were found in any of the neurotransmitter levels in adult female (Figure 3A–C) or male brain tissue at 9 mpf (Figure 3D–F).

Figure 3. DA, DOPAC, and dopamine turnover levels in adult female and male brain tissue (9 mpf).

Zebrafish embryos were exposed to 0, 0.3, 3, or 30 ppb atrazine through embryogenesis. Following developmental exposure, embryos were allowed to mature under normal conditions until 9 mpf. Zebrafish were sexed and the brain was dissected for HPLC analysis. No significant alterations occurred, as assessed by ANOVA in (A) DA (p=0.3207), (B) DOPAC (p=0.4529), or (C) dopamine turnover for females (p=0.1357) or in males in (D) DA (p=0.2914), (E) DOPAC (p=0.6828), or (F) dopamine turnover (p=0.6934) due to an embryonic atrazine exposure (n=8). Error bars indicate standard deviation.

3.3 Neurotransmitter analysis of serotonin, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, and serotonin turnover in adult female and male brain exposed to atrazine during embryogenesis

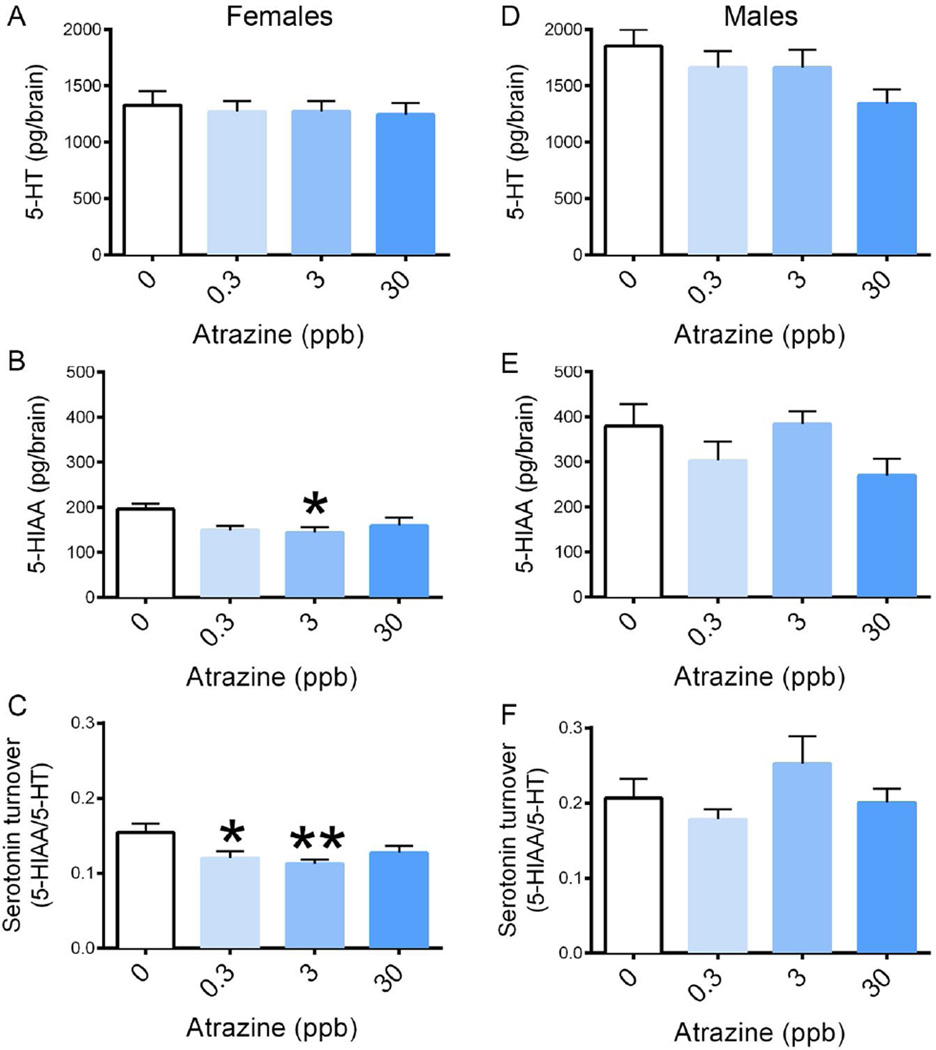

While no significant alterations were observed in 5-HT in the adult females exposed to atrazine during embryogenesis (Figure 4A), a significant reduction in 5-HIAA was observed in adult females exposed to 3 µg/L atrazine (Figure 4B, p=0.0448). In addition, an embryonic atrazine exposure also resulted in a reduction in serotonin turnover (5-HIAA/5-HT) in the 0.3 and 3 µg/L atrazine treatments in the adult female brain (Figure 4C, p=0.0182). No statistical significant alterations were observed in any of the neurotransmitter levels in the adult male brain male (Figure 4D–F).

Figure 4. 5-HT, 5-HIAA, and serotonin turnover levels in adult female and male brain tissue (9 mpf).

Zebrafish embryos were developmentally exposed to 0, 0.3, 3, or 30 ppb atrazine through embryogenesis and then allowed to mature under normal conditions until 9 mpf. Brain tissue was dissected and HPLC was performed. Results showed there was no significant alterations in (A) 5-HT due to any of the atrazine treatments in female brain tissue (p=0.9522). A significant decrease in (B) 5-HIAA at the 3 ppb atrazine treatment was observed (p=0.0448) along with a decrease in (C) serotonin turnover at 0.3 and 3 ppb atrazine (p=0.0182). No significant alterations occurred in (D) 5-HT (p=0.1192), (E) 5-HIAA (p=0.1287), or (F) serotonin turnover (p=0.2316) due to embryonic atrazine exposure in adult male brain tissue (n=8, *p<0.05, **p<0.02). Error bars indicate standard deviation.

3.4 Neurotransmitter analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid in the adult female and male brain tissue exposed to atrazine during embryogenesis

No statistical significant differences were found in GABA levels at any of the atrazine treatments in either sex (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Neurotransmitter analysis of GABA in 9 month old adult female and male brain tissue.

Zebrafish embryos were exposed to 0, 0.3, 3, or 30 ppb atrazine through embryogenesis. Following developmental exposure, embryos were allowed to mature under normal conditions until 9 mpf. Zebrafish were sexed and the brain was dissected for HPLC analysis. No significant alterations occurred, as assessed by ANOVA in GABA levels in (A) female (p=0.0794) or in (B) male brain tissue (p=0.8185) due to an embryonic atrazine exposure (n=8). Error bars indicate standard deviation.

3.5 Transcriptome microarray analysis of adult female brain tissue

Initial results revealed 2,711 probes significantly altered in the 0.3 µg/L group (Supplementary Table 1), while the 3 µg/L group had considerably fewer altered probes with 120 probes showing significant change (Supplementary Table 2). The 30 ppb group showed a larger response with 638 probes being significantly altered (Supplementary Table 3). After removal of redundant probes as well as probes that did not have well defined gene functions or information, there were expression alterations in 1,928 mapped genes in the 0.3 µg/L treatment group, 89 genes in the 3 µg/L group, and 435 genes in the 30 µg/L group. In the adult females exposed to 3 or 30 µg/L atrazine during embryogenesis, a majority of the observed genes were down-regulated with 89.2% of the genes in the 3 µg/L group showing a negative change and 74% negatively regulated in the 30 µg/L group. The 0.3 µg/L gene list was a mixture of up and down-regulated genes with 47% showing an increase in expression compared to 53% being negatively regulated. Of these differentially expressed genes, 39 were common among all three treatments (Table 2). The aforementioned gene numbers are the known human orthologs of the zebrafish genes found to be altered by microarrays and these human gene designations were used in subsequent gene enrichment analyses. Significantly altered gene lists for each of the treatment groups were uploaded into IPA for subsequent gene ontology analyses. The most enriched physiological and system development functions for the 0.3 µg/L treatment group were nervous system function and development defined as functions associated with the normal development and function of the cells, tissues and organs that make up the nervous system as well as functions specific to the nervous system; tissue development described as functions associated with the normal development and differentiation of tissues and the formation of tissue through the association of cells; and embryonic development and behavior defined as functions associated with the development and growth of embryos (Table 3). The 3 ppb group showed a similar response as pathways enriched for this treatment showed changes to genes involved in nervous system function and development and tissue development. In addition, organismal development pathways described as functions associated with the normal development, differentiation, and formation of organs and behavioral pathways defined as functions associated with the behavior of multicellular organisms, primarily humans, mice and rats were also enriched (Table 4). Pathways enriched in the 30 µg/L treatment group were identical to those found enriched in the 3 µg/L treatment group (Table 5). Moreover, in the top canonical pathways that were enriched in these respective treatments, circadian rhythm was shared between the 3 and 30 µg/L treatment groups with the PER1 and PER3 clock genes being changed in both treatments. In addition, these two genes were also changed in the 0.3 µg/L treatment and were down-regulated in all three treatments.

Table 2.

Overlap of genes significantly altered in adult female brain tissue from an embryonic exposure to atrazine in all three treatment groups.

| ABCD2 | Molecular Transport | Down |

| ADCY1 | Signal Transduction | Down |

| AIM1 | Unknown | Down |

| ANO3 | Molecular Transport | Down |

| APLP2 | Neurological Function | Down |

| CAMTA2 | Calmodulin-binding transcription factor | Down |

| CHD9 | Transcriptional Regulation | Down |

| CORIN | Peptide and Hormone Processing | Down |

| FAM120C | Unknown | Down |

| FRAS1 | Membrane Development | Down |

| GAD1 | Neurological Function | Down |

| GBP1 | Cellular Processes | Up |

| ITGAL | Cell Adhesion | Down |

| JAZF1 | Transcriptional Regulation | Down |

| KCTD15 | Organismal Development | Down |

| KIAA1737 | Unknown | Down |

| MEF2C | Transcriptional Regulation | Down |

| MLL4 | Chromatin modification | Up |

| MYCBP2 | Ubiquitin Ligase | Down |

| NCOR2 | Transcriptional Silencing | Down |

| NFIC | Transcriptional Regulation | Down |

| NRXN2 | Cell Adhesion and Receptor Activity | Down |

| PCLO | Synapse Function | Down |

| PDE10A | Signal Transduction | Down |

| PER1 | Circadian Rhythm | Down |

| PER3 | Circadian Rhythm | Down |

| PID1 | Protein Binding | Down |

| PLEKHO2 | Phospholipid Binding | Down |

| PSMB9 | Endopeptidase Protein | Up |

| RELN | Neurological Function | Down |

| SHANK3 | Scaffold Protein | Down |

| SOCS5 | Cell Growth | Down |

| THRA | Thyroid Hormone Regulation | Down |

| THSD7B | Membrane Function | Down |

| TIAM1 | Molecular Signaling | Down |

| TMEM72 | Membrane Function | Up |

| ZBTB47 | Transcriptional Regulation | Down |

| ZIC2 | Gene Expression | Up |

| ZNF729 | Regulation of Transcription | Up |

Table 3.

Gene enrichment in adult female brain tissue from an embryonic atrazine exposure of 0.3 ppb.

| NERVOUS SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTION | 1.25E-14 – 3.82E-03 | 389 |

| Axonogenesis | 2.60E-09 | 45 |

| Synaptic Transmission | 2.73E-09 | 73 |

| Neuritogenesis | 1.71E-11 | 96 |

| Memory | 3.19E-04 | 39 |

| TISSUE DEVELOPMENT | 1.71E-11 – 3.77E-03 | 312 |

| Development of Cerebral Cortex | 1.34E-06 | 30 |

| Plasticity of Synapse | 1.55E-04 | 23 |

| Formation of Embryonic Tissue | 1.77E-03 | 47 |

| Development of Pituitary Gland | 7.52E-04 | 11 |

| Formation of Dendrites | 3.62E-04 | 22 |

| EMBRYONIC DEVELOPMENT | 8.59E-10 – 3.17E-03 | 262 |

| Development of Body Axis | 3.35E-05 | 100 |

| Branching of Axons | 5.33E-05 | 17 |

| Development of Head | 4.52E-06 | 88 |

| Formation of Embryonic Tissue | 1.77E-03 | 47 |

| BEHAVIOR | 2.59E-12 – 2.49E-03 | 205 |

| Cognition | 1.84E-06 | 73 |

| Anxiety-like Behavior | 1.52E-05 | 13 |

| Learning | 1.78E-05 | 66 |

| Emotional Behavior | 5.13E-07 | 48 |

| Locomotion | 7.31E-09 | 64 |

Derived from the likelihood of observing the degree of enrichment in a gene set of a given size by chance alone.

Classified as being differentially expressed that relate to the specified function category; a gene may be present in more than one category.

Table 4.

Gene enrichment in adult female brain tissue from an embryonic atrazine exposure of 3 ppb.

| NERVOUS SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTION | 1.49E-06 – 1.35E-02 | 26 |

| Morphology of Nervous System | 1.82E-05 | 15 |

| Morphology of Brain | 1.36E-04 | 10 |

| Long-Term Potentiation | 1.01E-03 | 6 |

| TISSUE DEVELOPMENT | 1.49E-06 – 1.35E-02 | 24 |

| Development of Brain | 5.68E-04 | 9 |

| Development of Neurons | 1.49E-06 | 8 |

| Development of Forebrain | 5.03E-03 | 5 |

| ORGANISMAL DEVELOPMENT | 2.00E-05 – 1.1E-02 | 22 |

| Size of Body | 2.48E-03 | 12 |

| Development of Brain | 5.68E-04 | 9 |

| BEHAVIOR | 7.96E-05 – 1.35E-02 | 15 |

| Locomotion | 7.96E-05 | 8 |

| Behavior | 2.99E-04 | 14 |

| Circadian Rhythm | 5.83E-04 | 4 |

Derived from the likelihood of observing the degree of enrichment in a gene set of a given size by chance alone.

Classified as being differentially expressed that relate to the specified function category; a gene may be present in more than one category.

Table 5.

Gene enrichment in adult female brain tissue from an embryonic atrazine exposure of 30 ppb.

| NERVOUS SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTION | 2.34E-11 – 1.11E-02 | 112 |

| Coordination | 2.15E-06 | 18 |

| Differentiation of Neurons | 1.29E-05 | 25 |

| Neurotransmission | 2.81E-04 | 23 |

| Development of Central Nervous System | 7.62E-08 | 39 |

| TISSUE MORPHOLOGY | 9.07E-08 – 1.11E-02 | 116 |

| Abnormal Morphology of Embryonic | 8.55E-04 | 26 |

| Tissue | 9.58E-05 | 20 |

| Morphology of Neurons Abnormal Morphology of Extraembryonic Tissue | 8.55E-03 | 11 |

| ORGANISMAL DEVELOPMENT | 7.11E-10 – 1.12E-02 | 135 |

| Size of Animal | 4.84E-06 | 16 |

| Development of Body Axis | 1.55E-03 | 29 |

| Endothelial Cell Development | 4.16E-03 | 17 |

| Growth of Organism | 4.98E-03 | 24 |

| BEHAVIOR | 4.32E-08 – 8.95E-03 | 60 |

| Locomotion | 1.37E-05 | 21 |

| Behavior | 4.32E-08 | 54 |

| Cognition | 2.64E-03 | 20 |

| Learning | 6.28E-03 | 18 |

Derived from the likelihood of observing the degree of enrichment in a gene set of a given size by chance alone.

Classified as being differentially expressed that relate to the specified function category; a gene may be present in more than one category.

3.6 Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) confirmation of microarray data

A subset of genes found to be significantly altered by microarrays were independently confirmed by qPCR. We observed a high level of agreement between the genes found to be altered on the expression arrays and qPCR analysis (Table 6). We confirmed expression alterations in all three atrazine treatments for PER3, APLP2, and RELN (p=0.0005, 0.0008, 0.071, respectively). In addition, array confirmation of ABCD2 in the 0.3 and 30 µg/L atrazine treatment was observed (p=0.013). However, while the 3 µg/L treatment also showed a down regulation trend, this treatment was not significantly different from the control treatment group in the qPCR data. Expression of arginine vasopressin (AVP) was also included in this analysis as a gene without significant expression alterations in the microarray experiments and was confirmed not to be changed by atrazine exposure in the qPCR experiment (p=0.43).

Table 6.

qPCR comparison to microarray expression changes.

| Seq. ID | Gene Symbol |

Array – 0.3 ppba |

qPCR 0.3 ppba |

Array 3 ppb |

qPCR 3 ppb |

Array 30 ppb |

qPCR 30 ppb |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_131584 | PER3 | −0.90535* | −1.332* | −1.484* | −0.934* | −1.614* | −1.153* | p=0.0005 |

| ENSDART00000082522 | ABCD2 | −1.37128* | −1.6036* | −0.766* | −0.5206 | −0.916* | −0.6042* | p=0.013 |

| B1672476 | APLP2 | −1.45523* | −1.6655* | −1.100* | −1.4711* | −1.794* | −1.616* | p=0.0008 |

| ZV700S00003471 | RELN | −1.43029* | −1.9516* | −1.543* | −0.8271* | −1.896* | −0.6662* | p=0.0071 |

| NM_183346 | AVP | −0.531 | −1.7483 | −0.132 | 1.45994 | 0.263 | −0.0078 | p=0.43 |

Values are expressed as log2 expression of atrazine treatment over control (0 ppb).

Denotes treatment is significantly different from the control treatment (0 ppb) at p<0.05.

4.0 DISCUSSION

There are several studies in recent years investigating the impacts of atrazine exposure on human health with evidence suggesting weak correlations as well as several suggesting links to adverse health effects including adverse birth outcomes, endocrine disruption, and carcinogenesis (Cragin et al. 2011; Freeman et al. 2011; Rinsky et al. 2012). In addition to human studies, numerous animal studies aimed at identifying mode(s) of action through which atrazine exerts its effects have been completed. Considerable evidence points to effects on the hypothalamus-pituitary axis and the disruption of sex hormones (Cooper et al. 2000; Fraites et al. 2009; Foradori et al. 2009). In particular, several reports point to the disruption of LH release from the pituitary gland suggesting that atrazine may directly affect the pituitary gland. The endocrine system is a highly complex system that is composed of multiple glands that work alongside the CNS to regulate numerous processes including normal hormonal and reproductive function. Due to this in tandem relationship, understanding the neurotoxic effects of atrazine is necessary in elucidating its mechanisms of action due to its ability to readily cross the BBB (Ross et al. 2009).

The effects of atrazine on the dopaminergic system have been well studied both in vitro and in vivo. These studies have encompassed a wide array of doses and exposure periods. In vitro studies have shown that atrazine exposure disrupts DA homeostasis in catecholaminergic PC12 cells (Das et al. 2000), rat striatal slices (Filipov et al. 2007), and striatal synaptic vesicles (Hossain and Filipov, 2008), as well as the disruption of morphological differentiation of N27 dopaminergic cells (Lin et al. 2013b). In vivo studies thus far, show numerous treatments and exposure regimens which have provided a range of results. Studies investigating embryonic and or/developmental atrazine exposure are limited. One previous study examining the effects of gestational and lactational exposure found an increase in striatal DA and a decrease in dopamine turnover. No change was observed in DOPAC or in 5-HT (Lin et al. 2014b). These results are in partial agreement with our study in that we did not observe a change in 5-HT in our zebrafish larvae.

Studies aiming to address the effects of atrazine exposure in adult models are in greater abundance. A 10 day atrazine exposure at very high doses of 125 and 250 mg/kg reported an increase in DA in striatal tissue (Lin et al. 2013a). Utilizing an albino rat model, research showed that a dose of 100 mg/kg over a two-week period decreased DA and DOPAC in the striatum six days after dose completion. In addition, no significant alterations were found three months after dosing was completed (Rodriguez et al. 2013). These two studies provide conflicting data. However, it is necessary to identify the differences in dose, length and time period of exposure, and rat versus mouse models.

Identifying the later in life disruption of dopaminergic systems caused by atrazine during development or during the juvenile period is still ongoing. A study of juvenile rats that were dosed from post-natal day (PND) 22–62 found a decrease in DA levels in the striatum in males at 25 and 50 mg/kg one year after dosing was complete. Females also showed a decrease in striatal DA at 50 mg/kg one year after dosing (Li et al. 2014). Previous literature exposing juvenile male rats to atrazine caused a decrease in DA and DOPAC immediately following exposure, while neurotransmitter analysis at 8 and 48 days after completion of exposure caused no significant alterations in DA or DOPAC (Coban et al. 2007). Although these atrazine treatments encompassed a wide range of doses (5, 25, 125, and 250 mg/kg) and exposure periods these results are similar to those reported here. An additional study, identifying gestational and lactational exposure of atrazine on adult offspring also found results in agreement with the adult male findings in our study. Dams and offspring were exposed to 3 mg/L atrazine from GD 6 to PND 23. Striatal tissue revealed no significant alterations in DA, DOPAC, or dopamine turnover in adult male and female offspring. Also, perirhinal cortex tissue revealed no alterations in DA or DOPAC in adult male offspring; however, a significant decrease occurred in DOPAC in adult females (Lin et al., 2014b). Of interesting note, is the difference in DOPAC levels in female offspring.

In the current study, zebrafish were exposed through the end of embryogenesis (3 dpf), and then allowed to mature under normal conditions until 7 dpf or 9 mpf when analysis was completed. We did not observe any significant decreases in DA or identify a noticeable dose-response in the zebrafish larvae. Furthermore, results indicate that developmental low dose atrazine exposure of 0.3, 3, or 30 µg/L did not alter DA, DOPAC, or DA turnover in brain tissue of adult males. However, a decreasing dose-response in DA and DOPAC was noted, although not statistically significant. Furthermore, developmental atrazine exposure did not elicit significant alterations in DA, DOPAC, or dopamine turnover in adult female brain tissue. The lack of significance within the dopaminergic system following an embryonic atrazine exposure further supports the working hypothesis that atrazine exerts its adverse effects through the endocrine system by way of the HPG and HPA axes (Cooper et al. 2000; Foradori et al. 2009, 2013; Fraites et al. 2009).

The second monoamine neurotransmitter studied was 5-HT, its metabolite 5-HIAA, and serotonin turnover. Our results showed that atrazine exposure did not alter 5-HT in zebrafish larvae or in adult male brain tissue following developmental exposure. It was observed that the 3 µg/L treatment caused a slight increase in serotonin turnover; however, it was not statistically significant. Significant decreases were observed in 5-HIAA in adult female brain tissue at 3 µg/L as well as serotonin turnover at 0.3 and 3 µg/L atrazine. Literature addressing the effects of atrazine on 5-HT and its metabolites is limited with primary focus on male models. Currently, it has been shown that atrazine exposure of 125 and 250 mg/kg increased 5-HIAA and serotonin turnover in striatal tissue of adult male mice (Lin et al. 2013a). An additional study found that atrazine exposure of 100 mg/kg showed a decrease in 5-HIAA in the striatal tissue in the adult male rodent; however, after three months this decrease was no longer present (Rodriguez et al. 2013). Although these studies show that atrazine exposure increased 5-HIAA and serotonin turnover, it is of key importance to recognize that these animals were treated during adulthood. A previous study examining the effects of gestational and lactational exposure of atrazine revealed female offspring to have a significant decrease in 5-HT in the perirhinal cortex following an atrazine exposure of 3 mg/L (Lin et al., 2014b). Although our reduction occurred in 5-HIAA and in serotonin turnover, this previous study further supports the hypothesis that atrazine elicits an effect on the serotonergic system. The mechanisms behind the observed changes are still under investigation. One hypothesis is focused on the metabolism of the serotonin precursor, tryptophan. A recent study exposing male mice to 125 mg/kg of atrazine for 10 days found that the mice displayed a decreasing trend in tryptophan and an increasing trend in its metabolite indolepyruvate and the indolepyruvate/tryptophan ratio. This study indicates that short term atrazine exposure can increase the metabolism of tryptophan, therefore, explaining the previously described increase in 5-HIAA (Lin et al. 2013a). However, a decrease in tryptophan over time can result in a decrease in 5-HT and 5-HIAA synthesis (Biskup et al., 2012) providing a potential mechanism behind the observed decrease in 5-HIAA and serotonin turnover in adult female zebrafish in this study.

Our study is innovative in that it is the first to examine the later life effects of an embryonic low dose atrazine exposure on the serotonergic system. Observing the decreases in 5-HIAA and serotonin turnover, helps provide support that the mechanism of atrazine toxicity is endocrine based. It is known that 5-HT plays a role in the regulation of the HPA axis (Heisler et al. 2007). Once the HPA axis has been activated, the end result is the release of glucocorticoids by the adrenal cortex. One of the primary events in the HPA axis is the release of corticosterone (CORT). It has been shown that when 5-HT is increased, a corresponding increase in CORT occurs, while a decrease in 5-HT causes a decrease in CORT. It is hypothesized that this alteration in CORT is due to 5-HT stimulation of the corticotropin releasing neurons of the hypothalamus (Heisler et al. 2007). Although, we did not see significant alterations in 5-HT, our observed decreases in its metabolite and turnover implicate a potential sex specific neurotoxic effect that is linked to its endocrine disruptive properties. However, it should be noted that at this time we do not know if changes in the brain weight and/or size may also be occurring following atrazine exposure and will need to be addressed in a future study.

The last neurotransmitter that was analyzed was GABA. Results showed no significant alterations in GABA levels in larvae as well as female and male brain tissue in any of the atrazine treatments. The importance of observing the effects of atrazine on GABA is necessary due to its association with the HPG axis. GABAergic stimulation is known to decrease catecholamine availability as well as regulate gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) and LH release (Das et al. 2000). It has also been shown that atrazine binds to the GABAA receptor (Shafer et al. 1999). Therefore, a potential mechanism for the known reduction in GnRH and LH caused by atrazine could be exhibited through the GABAergic system. However, due to the complexity of atrazine effects on the CNS and endocrine systems, more research is needed in defining its potential effects on the GABAergic system.

Due to our observed effects of atrazine on the serotonin pathway in adult females that were exposed to atrazine during embryogenesis, transcriptomic profiles were assessed for genetic alterations that could be linked to our observed neurotransmitter alterations. Our laboratory has previously exposed zebrafish embryos to the same concentrations of atrazine and employed gene expression profiling in an effort to assess how the genomic landscape is immediately altered in response to an embryonic atrazine exposure.

Results from this study showed altered transcriptomic profiles associated with neuroendocrine and reproductive system development and function, cell cycle, and carcinogenesis (Weber et al. 2013). To our knowledge, no published studies have evaluated an embryonic exposure to atrazine and then subsequently assessed transcriptomic profiles later in life. In this study, we aimed to assess the genetic landscape associated with neurological function caused by embryonic atrazine exposure. Results showed a significant overlap in the physiological system development and function category which included nervous system development and function, tissue development, organismal development, and behavior between all three atrazine treatments. Due to our observed alterations in 5-HIAA and serotonin turnover, we assessed the enrichment of genes associated with the serotonergic pathway. Our transcriptomic profiles showed that an embryonic exposure to atrazine alters gene expression of several genes throughout the serotonergic pathway. These genes include GCH1, SPR, QDPR, TPH, MAO, VMAT, and the serotonin receptors HTR2C, HTR1A, and HTR4. These genes are necessary for the synthesis, transport, release, and metabolism of serotonin. Although our results indicate that atrazine does not directly alter serotonin levels, transcriptomic data provides support that an embryonic atrazine exposure leads to significant alterations in genes throughout the serotonergic pathway that are necessary for proper neurotransmitter function. RELN was also shown to be decreased across all atrazine treatments and plays an important role in neurotransmitter release and modulation of long-term potentiation (Peterson et al. 2011).

Alongside the serotonin system is the HPA axis; the body’s key stress response pathway. These two systems work in tandem and dysregulation of the HPA axis and serotonin system has been implicated in the pathology of anxiety-like disorders (Heisler et al. 2007). Transcriptomic results show genes associated with behaviors such as anxiety to be altered by the embryonic atrazine exposure. Embryonic atrazine exposure decreases the gene responsible for corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) which is needed for the downstream release of corticosterone. The decrease in CRH expression along with HTR2C and HTR1A which are key serotonin receptors within the CNS may play a role in the increase of anxiety-like behavior.

An additional behavioral category in which embryonic atrazine appears to affect is circadian rhythm. The circadian rhythm in animals is highly important in terms of overall health and reproduction and can be affected by serotonin. Our transcriptomic results have shown a decrease in PER1 and PER3 in all three atrazine treatments which are key regulators of circadian rhythm (Sanggaard et al. 2003).

5.0 Conclusions

In summary, we sought to identify a developmental origin associated with the adverse outcomes of an atrazine exposure. To examine this, our study was two-fold. First, our assessment of neurotransmitter levels (5-HT, 5-HIAA, 5-HIAA/5-HT, DA, DOPAC, DOPAC/DA, and GABA) at 7 dpf and at 9 mpf following an embryonic atrazine exposure resulted in alterations that were specific to females and the serotonergic system. To complement this data, a transcriptomic profile of adult female brain tissue was completed. Multiple genes associated with nervous system development and function, behavior, and tissue development were identified to be altered in all three atrazine treatments in adulthood following an embryonic atrazine exposure. Significant alterations in genes associated with serotonergic function and alterations in behavior were emphasized. The findings from this study provide support for a developmental origin of neurological alterations in adult females exposed to atrazine during embryogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Embryonic atrazine exposure does not alter neurotransmitter levels in larvae

Adult neurotransmitter alterations were female and serotonergic pathway specific

Genes associated with serotonergic pathway were altered in transcriptomic analysis

Findings support developmental origin of neurological alterations in adult females

Acknowledgements

The authors thank John Tan and the Genomic and Bioinformatics Core Facility at the University of Notre Dame for assistance in scanning the microarray.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [R15 ES019137 to J.L.F. and M.S. and R00 ES019879 to J.R.C].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Data: Supplementary data contain probe lists from each treatment group in the microarray analysis.

Contributor Information

Sara E. Wirbisky, Email: swirbisk@purdue.edu.

Gregory J. Weber, Email: gjweber@purdue.edu.

Maria S. Sepúlveda, Email: mssepulv@purdue.edu.

Changhe Xiao, Email: changhe@purdue.edu.

Jason R. Cannon, Email: cannonjr@purdue.edu.

Jennifer L. Freeman, Email: jfreema@purdue.edu.

REFERENCES

- Barker DJ, Godfrey KM, Gluckman PD, Harding JE, Owens JA, Robinson JS. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet. 1993;341:938–941. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91224-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Osmond C. Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Whales. Lancet. 1986;1:1077–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker TR, Peterson RE, Heideman W. Early dioxin exposure causes toxic effects in adult zebrafish. Toxicol Sci. 2013;135:241–250. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni V, Dessì-Fulgheri F, Zaccaroni M, Di Consiglio E, De Angelis G, Testai E, Santochirico M, Alleva E, Santucci D. Early exposure to low doses of atrazine affects behavior in juvenile and adult CD1 mice. Toxicology. 2011;279:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum LS, Fenton SE. Cancer and developmental exposure to endocrine disruptors. Environ. Health. Perspect. 2003;111:389–394. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskup CS, Sanchez CL, Arrant A, Van Swearingen AE, Kuhn C, Zepf FD. Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on brain serotonin function and concentrations of dopamine and norephinephrine in C57BL/6j and BALB-cJ mice. PloS One. 2012;7:e35916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM, Irizarry M, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oliogonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum information of publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coban A, Filipov NM. Dopaminergic toxicity associated with oral exposure to the herbicide atrazine in juvenile male C57BL/6 mice. J. Neurochem. 2007;100:1177–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RL, Stoker TE, Tyrey L, Goldman JM, McElroy WK. Atrazine disrupts the hypothalamic control of pituitary-ovarian function. Toxicol. Sci. 2000;53:297–307. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/53.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragin LA, Kesner JS, Bachand AM, Barr DB, Meadows JW, Krieg EF, Reif JS. Menstrual cycle characteristics and reproductive hormone levels in women exposed to atrazine in drinking water. Environ. Res. 2011;111:1293–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das PC, McElroy WK, Cooper RL. Differential modulation of catecholamines by chlorotriazine herbicides in pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells in vitro. Toxicol. Sci. 2000;56:324–331. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/56.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LK, Murr AS, Best DS, Fraites MJ, Zorrilla LM, Narotsky MG, Stoker TE, Goldman JM, Cooper RL. The effects of prenatal exposure to atrazine on pubertal and postnatal reproductive indices in the female rat. Reprod. Toxicol. 2011;32:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Esch C, Slieker R, Wolterbeek A, Woutersen R, De Groot D. Zebrafish as potential model for developmental neurotoxicity testing: A mini review. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2012;34:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, Zoeller RT, Gore AC. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocrine Reviews. 2009;30:293–342. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinoy D, Jirtle R. Environmental epigenomics in human health and disease. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2008;49:4–8. doi: 10.1002/em.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhouri WD, Nuñez JL, Trail F. Atrazine binds to the growth hormone-releasing hormone receptor and affects growth hormone gene expression. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1400–1405. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuer SK, Liu X, Donjacour A, Lin W, Simbulan RK, Giritharan G, Piane L, Kolahi K, Ameri K, Maltepe E, Rinaudo PF. Use of a mouse in vitro fertilization model to understand the developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis. Endocrinology. 2014;155:1956–1969. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipov NM, Stewart MA, Carr RL, Sistrunk SC. Dopaminergic toxicity of the herbicide atrazine in rat striatal slices. Toxicology. 2007;232:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foradori CD, Hinds LR, Hanneman WH, Legare ME, Clay CM, Handa RJ. Atrazine inhibits pulsatile luteinizing hormone release without altering pituitary sensitivity to a gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor agonist in female wistar rats. Biol. Reprod. 2009;81:40–45. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foradori CD, Zimmerman AD, Hinds LR, Zuloaga KL, Brechenridge CB, Handa RJ. Atrazine inhibits pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) release without alterting GnRH messenger RNA or protein levels in the female rat. Biol. Reprod. 2013;88:1–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.102277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraites MJ, Cooper RL, Buckalew A, Jayaraman S, Mills L, Laws S. Characterization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to atrazine and metabolites in the female rat. Toxicol. Sci. 2009;112:88–99. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraites MJ, Narotsky MG, Best DS, Stoker TE, Davis LK, Goldman JM, Hotchkiss MG, Klinefelter GR, Kamel A, Qian Y, Podhorniak L, Cooper RL. Gestational atrazine exposure: effects on male reproductive development and metabolic distribution in the dam, fetus, and neonate. Reprod. Tox. 2011;32:52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JL, Rayburn AL. Developmental impact of atrazine on metamorphing Xenopus laevis as revealed by nuclear analysis and morphology. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2005;24:1648–1653. doi: 10.1897/04-338r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JL, Weber GJ, Peterson SM, Nie LH. Embryonic ionizing radiation exposure results in expression alterations of genes associated with cardiovascular and neurological development, function, and disease and modified cardiovascular function in zebrafish. Front. Genet. 2014;268:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman LE, Rusiecki JA, Hoppin JA, Lubin JH, Koutros S, Andreotti G, Zahm SH, Hines CJ, Coble JB, Barone-Adesi F, Sloan J, Sandler DP, Blair A, Alavanja MC. Atrazine and cancer incidence among pesticide applicators in the agricultural health study (1994–2007) Environ. Health Perspect. 2011;119:1253–1259. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Lobenhofer EK, Wang C, Shippy R, Harris SC, Zhang L, Mei N, Chen T, Herman D, Goodsaid FM, Hurban P, Phillips KL, Xu J, Deng X, Sun YA, Tong W, Dragan YP, Shi L. Rat toxicogenomic study reveals analytical consistency across microarray platforms. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1162–1169. doi: 10.1038/nbt1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisler LK, Pronchuk N, Nonogaki K, Zhou L, Raber J, Tung L, Yeo G, O’Rahilly S, Colmers WF, Elmquist JK, Tecott LH. Serotonin activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis via serotonin 2C receptor stimulation. J. Neuroscience. 2007;27:6956–6964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2584-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M, Filipov NM. Alteration of dopamine uptake into rat striatal vesicles and synaptosomes caused by an in vitro exposure to atrazine and some of its metabolites. Toxicology. 2008;248:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe K, Clark MD, Torroja CF, Torrance J, Berthelot C, Muffato M, Collins JE, Humphray S, McLaren K, Matthews L, McLaren S, Sealy I, Caccamo M, Churcher C, Scott C, Barrett JC, Koch R, Rauch GJ, White S, Chow W, Kilian B, Quintais LT, Guerra-Assunção JA, Zhou Y, Gu Y, Yen J, Vogel JH, Eyre T, Redmond S, Banerjee R, Chi J, Fu B, Langley E, Maguire SF, Laird GK, Lloyd D, Kenyon E, Donaldson S, Sehra H, Almeida-King J, Loveland J, Trevanion S, Jones M, Quail M, Willey D, Hunt A, Burton J, Sims S, McLay K, Plumb B, Davis J, Clee C, Oliver K, Clark R, Riddle C, Elliot D, Threadgold G, Harden G, Ware D, Begum S, Mortimore B, Kerry G, Heath P, Phillimore B, Tracey A, Corby N, Dunn M, Johnson C, Wood J, Clark S, Pelan S, Griffiths G, Smith M, Glithero R, Howden P, Barker N, Lloyd C, Stevens C, Harley J, Holt K, Panagiotidis G, Lovell J, Beasley H, Henderson C, Gordon D, Auger K, Wright D, Collins J, Raisen C, Dyer L, Leung K, Robertson L, Ambridge K, Leongamornlert D, McGuire S, Gilderthorp R, Griffiths C, Manthravadi D, Nichol S, Barker G, Whitehead S, Kay M, Brown J, Murnane C, Gray E, Humphries M, Sycamore N, Barker D, Saunders D, Wallis J, Babbage A, Hammond S, Mashreghi-Mohammadi M, Barr L, Martin S, Wray P, Ellington A, Matthews N, Ellwood M, Woodmansey R, Clark G, Cooper J, Tromans A, Grafham D, Skuce C, Pandian R, Andrews R, Harrison E, Kimberley A, Garnett J, Fosker N, Hall R, Garner P, Kelly D, Bird C, Palmer S, Gehring I, Berger A, Dooley CM, Ersan-Ürün Z, Eser C, Geiger H, Geisler M, Karotki L, Kirn A, Konantz J, Konantz M, Oberländer M, Rudolph-Geiger S, Teucke M, Lanz C, Raddatz G, Osoegawa K, Zhu B, Rapp A, Widaa S, Langford C, Yang F, Schuster SC, Carter NP, Harrow J, Ning Z, Herrero J, Searle SM, Enright A, Geisler R, Plasterk RH, Lee C, Westerfield M, de Jong PJ, Zon LI, Postlethwait JH, Nüsslein-Volhard C, Hubbard TJ, Roest Crollius H, Rogers J, Stemple DL. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature. 2013;496:498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Ooi SL, Wu Z, Boeke JD. Use of mixture models in a microarray-based screening procedure for detecting differentially represented yeast mutant. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2003;2(1) doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1002. Article 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Dodd CA, Filipov NM. Short-term atrazine exposure causes behavioral deficits and disrupts monoaminergic systems in male C57BL/6 mice. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2013a;39:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Dodd CA, Filipov NM. Differentiation state-dependent effects of in vitro exposure to atrazine or its metabolite diaminochlorotriazine in a dopaminergic cell line. Life Sci. 2013b;92:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Roede JR, He C, Jones DP, Filipov N. Short term oral atrazine exposure alters the plasma metabolome of male C57BL/6 mice and disrupts α-linolenate, tryptophan, tyrosine and other major metabolic pathways. Toxicology. 2014a;326:130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Dodd CA, Xiao S, Krishna S, Ye X, Filipov NM. Gestational and lactational exposure to atrazine via the drinking water causes specific behavioral deficits an selectively alters monoaminergic systems in C57BL/6 mouse dams, juvenile and adult offspring. Toxicol Sci. 2014b;141:90–102. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Zhang P, Wang F, Yang J, Yang Z, Qin H. The relationship between early embryo development and tumourigenesis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010;14:2697–2701. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa-Acuña H, Frankenberger J, Hahn L, Carbajo C. Drinking-water herbicide exposure in Indiana and Prevalence of small-for-gestational-age and preterm delivery. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117:1619–1624. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson S, Zhang J, Weber GJ, Freeman JL. Global Gene Expression Analysis Reveals Dynamic and Developmental Stage–Dependent Enrichment of Lead-Induced Neurological Gene Alterations. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011;119:615–621. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson SM, Zhang J, Freeman JL. Developmental reelin expression and time point specific alterations from lead exposure in zebrafish. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2013;38:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkovic V, Djolai M, Matavulj M. Alterations in jejunal morphology and serotonin-containing enteroendocrine cells in peripubertal male rats associated with subchronic atrazine exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2011;74:2304–2309. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner JL, Enoch RR, Fenton SE. Adverse effects of prenatal exposure to atrazine during a critical period of mammary gland growth. Toxicol. Sci. 2005;87:255–266. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinsky JL, Hopenhayn C, Golla V, Browning S, Bush HM. Atrazine exposure in public drinking water and preterm birth. Public Health Rep. 2012;127:72–80. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez VM, Limón-Pacheco JH, Mendoza-Trejo MS, González-Gallardo A, Hernández-Plata I, Giordano M. Repeated exposure to the herbicide atrazine alters locomotor activity and the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system of the albino rat. Neurotoxicol. 2013;34:82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr JR, McCoy KA. A qualitative meta-analysis reveals consistent effects of atrazine on fresh water fish and amphibians. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118:20–32. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross MK, Jones TL, Filipov NM. Disposition of the herbicide 2-chloro-4-(ethylamino)-6-(isopropylamino)-s-triazine (Atrazine) and its major metabolites in mice: a liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis of urine, plasma, and tissue levels. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009;37:776–786. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.024927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanggaard KM, Hannibal J, Fahrenkrug J. Serotonin inhibits glutamate- but not PACAP induced per gene expression in the rat suprachiasmic nucleus at night. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;17:1245–1252. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer TJ, Ward TR, Meacham CA, Cooper RL. Effects of chlorotriazine herbicide, cyanazine, on GABAA receptors in cortical tissue from rat brain. Toxiocology. 1999;142:57–68. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(99)00133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Reid LH, Jones WD, Shippy R, Warrington JA, Baker SC, Collins PJ, de Longueville F, Kawasaki ES, Lee KY, Luo Y, Sun YA, Willey JC, Setterquist RA, Fischer GM, Tong W, Dragan YP, Dix DJ, Frueh FW, Goodsaid FM, Herman D, Jensen RV, Johnson CD, Lobenhofer EK, Puri RK, Schrf U, Thierry-Mieg J, Wang C, Wilson M, Wolber PK, Zhang L, Amur S, Bao W, Barbacioru CC, Lucas AB, Bertholet V, Boysen C, Bromley B, Brown D, Brunner A, Canales R, Cao XM, Cebula TA, Chen JJ, Cheng J, Chu TM, Chudin E, Corson J, Corton JC, Croner LJ, Davies C, Davison TS, Delenstarr G, Deng X, Dorris D, Eklund AC, Fan XH, Fang H, Fulmer-Smentek S, Fuscoe JC, Gallagher K, Ge W, Guo L, Guo X, Hager J, Haje PK, Han J, Han T, Harbottle HC, Harris SC, Hatchwell E, Hauser CA, Hester S, Hong H, Hurban P, Jackson SA, Ji H, Knight CR, Kuo WP, LeClerc JE, Levy S, Li QZ, Liu C, Liu Y, Lombardi MJ, Ma Y, Magnuson SR, Maqsodi B, McDaniel T, Mei N, Myklebost O, Ning B, Novoradovskaya N, Orr MS, Osborn TW, Papallo A, Patterson TA, Perkins RG, Peters EH, Peterson R, Philips KL, Pine PS, Pusztai L, Qian F, Ren H, Rosen M, Rosenzweig BA, Samaha RR, Schena M, Schroth GP, Shchegrova S, Smith DD, Staedtler F, Su Z, Sun H, Szallasi Z, Tezak Z, Thierry-Mieg D, Thompson KL, Tikhonova I, Turpaz Y, Vallanat B, Van C, Walker SJ, Wang SJ, Wang Y, Wolfinger R, Wong A, Wu J, Xiao C, Xie Q, Xu J, Yang W, Zhang L, Zhong S, Zong Y, Slikker W., Jr The MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) project shows inter- and intraplatform reproducibility of gene expression measurements. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1151–1161. doi: 10.1038/nbt1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA. EPA 816-F-02-013. Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2002. List of contaminants and their MCLs. [Google Scholar]

- Weber GJ, Sepulveda MS, Peterson SM, Lewis SL, Freeman JL. Transcriptome alterations following developmental atrazine exposure in zebrafish are associated with disruption of neuroendocrine and reproductive system function, cell cycle, and carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Sci. 2013;132:458–466. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. The zebrafish book: a guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Danio rerio) 5th ed. Eugene, Oregon: 2007. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel LT, Luempert LG, 3rd, Breckenridge CB, Tisdel MO, Stevens JT, Thakur AK, Extrom PJ, Eldridge JC. Chronic effects of atrazine on estrus and mammary tumor formation in female Sprague-Dawley and Fischer 344 rats. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. 1994;43:169–182. doi: 10.1080/15287399409531913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirbisky SE, Weber GJ, Lee J, Cannon JR, Freeman JL. Novel dose-dependent alterations in excitatory GABA during embryonic development associated with lead (Pb) neurotoxicity. Toxicol. Letters. 2014;229:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Lamb C, Smith M, Schaefer L, Carvan MJ, III, Weber DN. Developmental methylmercury exposure affects avoidance learning outcomes in adult zebrafish. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2012;4:85–91. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.