Abstract

BACKGROUND

Financial incentives promote many health behaviors, but effective ways to deliver health incentives remain uncertain.

METHODS

We randomly assigned CVS Caremark employees and their relatives and friends to one of four incentive programs or to usual care for smoking cessation. Two of the incentive programs targeted individuals, and two targeted groups of six participants. One of the individual-oriented programs and one of the group-oriented programs entailed rewards of approximately $800 for smoking cessation; the others entailed refundable deposits of $150 plus $650 in reward payments for successful participants. Usual care included informational resources and free smoking-cessation aids.

RESULTS

Overall, 2538 participants were enrolled. Of those assigned to reward-based programs, 90.0% accepted the assignment, as compared with 13.7% of those assigned to deposit-based programs (P<0.001). In intention-to-treat analyses, rates of sustained abstinence from smoking through 6 months were higher with each of the four incentive programs (range, 9.4 to 16.0%) than with usual care (6.0%) (P<0.05 for all comparisons); the superiority of reward-based programs was sustained through 12 months. Group-oriented and individual-oriented programs were associated with similar 6-month abstinence rates (13.7% and 12.1%, respectively; P = 0.29). Reward-based programs were associated with higher abstinence rates than deposit-based programs (15.7% vs. 10.2%, P<0.001). However, in instrumental-variable analyses that accounted for differential acceptance, the rate of abstinence at 6 months was 13.2 percentage points (95% confidence interval, 3.1 to 22.8) higher in the deposit-based programs than in the reward-based programs among the estimated 13.7% of the participants who would accept participation in either type of program.

CONCLUSIONS

Reward-based programs were much more commonly accepted than deposit-based programs, leading to higher rates of sustained abstinence from smoking. Group-oriented incentive programs were no more effective than individual-oriented programs. (Funded by the National Institutes of Health and CVS Caremark; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01526265.)

Financial incentives have been shown to promote a variety of health behaviors.1–8 For example, in a randomized, clinical trial involving 878 General Electric employees, a bundle of incentives worth $750 for smoking cessation nearly tripled quit rates, from 5.0% to 14.7%,8 and led to a program adapted by General Electric for its U.S. employees.9 Although incentive programs are increasingly used by governments, employers, and insurers to motivate changes in health behavior,10,11 their design is usually based on the traditional economic assumption that the size of the incentive determines its effectiveness. In contrast, behavioral economic theory suggests that incentives of similar size may have very different effects depending on how they are designed.12

For example, deposit or “commitment” contracts, whereby participants put some of their own money at risk and recoup it if they are successful in changing their behavior, have been used in a variety of online and employer-based behavioral-change programs. Because people are typically more motivated to avoid losses than to seek gains,13 deposit contracts should be more successful than reward programs. However, the need to make deposits may deter people from participating, and the overall effectiveness of deposit and reward programs has not been compared.14,15

Furthermore, incentives that target groups may be more effective than incentives that target individuals because people are strongly motivated by social comparisons.16–18 Collaborative incentives, whereby payments to successful group members increase with the overall success of the group, may add dimensions of interpersonal accountability and teamwork.19 Competitive designs, such as pari-mutuel schemes in which money deposited by group members who do not change their behavior gets distributed to group members who do, may amplify peoples’ aversions to loss by highlighting the regret they may feel if others benefit from their failure to change.20,21

We therefore evaluated incentive programs for smoking cessation that are based on rewards or deposit contracts and that are delivered at the individual or group level, comparing the interventions on three measures: acceptance, defined as the proportion of people who accept the incentive program when offered; overall effectiveness, assessed as the proportion of people offered each program who stop smoking; and efficacy, assessed as the proportion of people who stop smoking if they accept a given incentive program.

METHODS

TRIAL DESIGN

We conducted a five-group randomized, controlled trial comparing usual care with four incentive programs aimed at promoting sustained abstinence from smoking. The protocol (available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org) was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania. The first author vouches for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol.

STUDY POPULATION

We used a multifaceted recruitment scheme (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org) to enroll CVS Caremark employees or their relatives and friends across the United States. Eligible participants were at least 18 years of age, reported smoking at least 5 cigarettes per day, had Internet access, and indicated an interest in learning about ways to stop smoking. Recruitment occurred from February 2012 through October 2012. Using the Way to Health Web-based research portal created for this and other studies,22 participants opened an account, electronically signed the informed-consent document, and completed a baseline questionnaire. Participants were told that they would be paid for completing questionnaires and submitting samples to confirm smoking abstinence and that the study tested different ways of providing financial incentives to promote cessation. To dissuade nonsmokers from enrolling, we also informed potential participants that we would randomly screen for baseline smoking.

After randomization, participants learned the details of their assigned intervention, were asked to accept or decline their intervention, and chose a target quit date between 1 and 90 days after enrollment. We then selected a random sample of 5% of these enrolled participants to undergo baseline cotinine screening and offered $100 for completing a cotinine assay.

RANDOMIZATION AND INTERVENTIONS

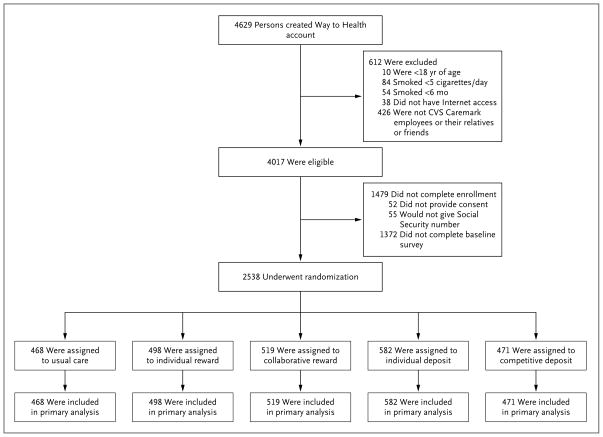

Participants were randomly assigned on an individual basis to one of five groups (Fig. 1). Randomization was stratified according to two dichotomous variables: whether participants had full health care benefits through CVS Caremark and whether their annual household income was at least $60,000 (the CVS Caremark workforce median) or less than $60,000. We developed an adaptive randomization algorithm23–26 that updated the assignment probabilities to the five groups after every third enrolled participant. Updated probabilities reflected the inverse of the proportion of participants assigned to that group who accepted the intervention, relative to total acceptance across groups.26 This approach balances recruitment of accepting participants across groups by increasing the odds of randomization to interventions that previous participants declined.

Figure 1.

Assessment for Eligibility and Randomization.

All the participants were offered usual care, consisting of information about local smoking-cessation resources, cessation guides produced by the American Cancer Society, and, for the 41% of the participants receiving health benefits through CVS Caremark, free access to a behavioral-modification program and nicotine-replacement therapy. Participants assigned to the two individual-incentive groups were also eligible to receive $200 if they had biochemically confirmed abstinence at each of three times: 14 days, 30 days, and 6 months after their target quit dates. Participants would get an additional $200 bonus at 6 months, for a total of $800 (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). In the individual-deposit group, this sum included a $150 deposit that would be refunded to participants who quit smoking.

In the collaborative-reward and competitive-deposit groups, cohorts of six smokers each were formed on a rolling basis, linking participants who selected quit dates nearest each other. In the collaborative-reward group, payments to successful group members at each time point increased with increasing group success rates, from $100 per time point if one participant quit to $600 per time point per participant if all six quit. We sought to foster collaboration among participants with the use of a Web-based chat room through which they could communicate throughout the study.

In the competitive-deposit group, $150 deposits from each of six group members, plus a $450 matching reward per member ($3,600 total), was redistributed among members who quit at each time point. For example, if only two participants in a group quit at 14 days but returned to smoking by 30 days, those two participants would receive $600 each at 14 days, and there would be no further payouts to the members of that group. Members of competitive cohorts received accurate but anonymous descriptions of their competitors to make vivid the possibility that others might benefit from their own lack of change21 without enabling participants to undermine a competitor’s efforts.

Participants in the group-incentive groups were also given a $200 bonus if they sustained abstinence through 6 months. Thus, the four interventions differed in how incentives would accrue and be disbursed (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix), but the payment schedule and bonus were identical, and on the basis of anticipated success rates, we estimated that each intervention carried an expected value of $800.

OUTCOMES

The primary outcome was sustained abstinence from smoking for 6 months after the target quit date.27 Achievement of sustained abstinence required that submitted saliva samples had a cotinine concentration of less than 10 ng per milliliter28 at 14 days, 30 days, and 6 months. For users of nicotine-replacement therapy, a urinary sample with an anabasine concentration of less than 3 ng per milliliter was considered to show sustained abstinence.29 Participants who did not submit samples were coded as actively smoking. Secondary outcomes included the initial quit rate at 14 days, sustained abstinence for 30 days, and sustained abstinence through 12 months (i.e., 6 months after the final incentive disbursement).

Incentive acceptance rates reflected the proportion of participants assigned to that incentive who agreed to the contract. In the two groups requiring deposits, we considered participants to have accepted the intervention if they made $150 deposits by credit or debit card within 60 days after enrollment or before their selected quit date, whichever came first. Consenting participants who declined their assigned program remained in their assigned group for intention-to-treat analyses and were treated identically to those in the usual-care group.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We specified three analyses corresponding to the aims of the study. First, we used logistic regression to compare acceptance of the interventions, adjusting for the two variables according to which the randomization was stratified.30 Second, we conducted intention-to-treat analyses using logistic regression to compare the effectiveness of incentive programs among all randomly assigned participants. Third, we compared the efficacy of the interventions. We first conducted traditional per-protocol analyses, comparing groups of participants who accepted different interventions. However, because such analyses are subject to selection biases,31 our primary approach to measure efficacy modeled the randomization group as an instrumental variable32,33 in analyses of the complier average treatment effect.34–36 These analyses, described in detail in the Supplementary Appendix, used data on all randomly assigned participants to estimate treatment effects for participants who would have accepted each intervention.

We estimated that a sample of 2185 participants would provide 80% power to detect absolute differences of at least 7.5 percentage points in the rate of sustained abstinence between any one of the three novel incentive programs and the individual-reward program. Details of this calculation are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

RESULTS

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

Overall, 2538 participants were enrolled. The demographic and smoking-related characteristics of the participants were balanced across the five study groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (Intention-to-Treat Population).*

| Characteristic | Usual Care (N = 468) | Individual Reward (N = 498) | Collaborative Reward (N = 519) | Individual Deposit (N = 582) | Competitive Deposit (N = 471) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age — yr | |||||

| Median | 34 | 32 | 32 | 33 | 33 |

| Interquartile range | 26–47 | 25–46 | 25–45 | 25–48 | 25–45 |

| Female sex — no. (%) | 300 (64) | 312 (63) | 322 (62) | 367 (63) | 293 (62) |

| Race — no. (%)† | |||||

| White | 365 (78) | 409 (82) | 387 (75) | 452 (78) | 376 (80) |

| Black | 43 (9) | 44 (9) | 58 (11) | 54 (9) | 49 (10) |

| Other | 60 (13) | 45 (9) | 74 (14) | 76 (13) | 46 (10) |

| Years of education‡ | |||||

| Median | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Interquartile range | 12–14 | 12–14 | 12–15 | 12–15 | 12–15 |

| Annual household income — no. (%) | |||||

| <$60,000 | 346 (74) | 375 (75) | 382 (74) | 403 (69) | 358 (76) |

| ≥$60,000 | 122 (26) | 123 (25) | 137 (26) | 179 (31) | 113 (24) |

| Health insurance — no. (%)§ | |||||

| CVS Caremark employee | |||||

| Enrolled in CVS Caremark health care plan | 152 (32) | 174 (35) | 177 (34) | 213 (37) | 168 (36) |

| Not enrolled in CVS Caremark health care plan | 139 (30) | 136 (27) | 151 (29) | 180 (31) | 146 (31) |

| Relative or friend of CVS Caremark employee | |||||

| Enrolled in CVS Caremark health care plan | 36 (8) | 33 (7) | 26 (5) | 29 (5) | 36 (8) |

| Not enrolled in CVS Caremark health care plan | 141 (30) | 155 (31) | 165 (32) | 160 (27) | 121 (26) |

| Smoking history | |||||

| No. of cigarettes smoked per day | |||||

| Median | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Interquartile range | 10–20 | 10–20 | 9–20 | 10–20 | 10–20 |

| Duration of regular smoking — yr | |||||

| Median | 15 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 14 |

| Interquartile range | 6–26 | 6–25 | 6–25 | 6–25 | 7–25 |

| Age at first smoking — yr | |||||

| Median | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| Interquartile range | 15–19 | 15–19 | 15–19 | 15–19 | 15–19 |

| Level of nicotine dependence — no. (%)¶ | |||||

| Low | 101 (22) | 111 (22) | 118 (23) | 122 (21) | 95 (20) |

| Low to moderate | 148 (32) | 155 (31) | 152 (29) | 185 (32) | 141 (30) |

| Moderate | 194 (41) | 210 (42) | 229 (44) | 251 (43) | 215 (46) |

| High | 25 (5) | 22 (4) | 20 (4) | 24 (4) | 20 (4) |

| Stage of change — no. (%)|| | |||||

| Preparation | 300 (64) | 312 (63) | 327 (63) | 372 (64) | 312 (66) |

| Contemplation | 168 (36) | 186 (37) | 192 (37) | 210 (36) | 158 (34) |

| Successfully quit for a 24-hr period in past year — no. (%) | 300 (64) | 307 (62) | 328 (63) | 361 (62) | 294 (62) |

| Ever used NRT or assistance to quit smoking — no. (%) | 340 (73) | 384 (77) | 384 (74) | 421 (72) | 350 (74) |

| Currently using other methods to quit smoking — no. (%)** | 65 (14) | 51 (10) | 71 (14) | 73 (13) | 47 (10) |

The intention-to-treat population includes all participants who underwent randomization to the five study groups. There were no significant differences between the study groups in any of the baseline characteristics listed (P>0.05). NRT denotes nicotine-replacement therapy.

Race was self-reported.

Years of education range from grade 1 to 17, with 17 representing “at least some graduate school” and 13 to 16 representing 1 to 4 years of college.

The CVS Caremark health care plan includes free access to a behavioral-modification program and NRT.

The level of dependence is based on the score on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence. Scores range from 1 to 10, with higher scores indicating a more intense physical dependence on nicotine. Low dependence corresponds to a score of 1 or 2, low-to-moderate dependence a score of 3 or 4, moderate dependence a score of 5 to 7, and high dependence a score of 8 to 10.

The participants were asked, “Are you seriously thinking of quitting smoking?” and were given three options to select: yes, within the next 30 days (preparation stage); yes, within the next 6 months (contemplation stage); or no, not thinking of quitting (precontemplation stage). The values for contemplation stage include 10 participants in the precontemplation stage: 2 participants in the usual-care group, 2 participants in the individual-reward group, 2 participants in the collaborative-reward group, 3 participants in the individual-deposit group, and 1 participant in the competitive-deposit group. Data were missing for 1 participant in the competitive-deposit group.

Participant is currently using NRT, behavioral therapy, prescription medication, or other method to quit smoking.

ACCEPTANCE OF INTERVENTIONS

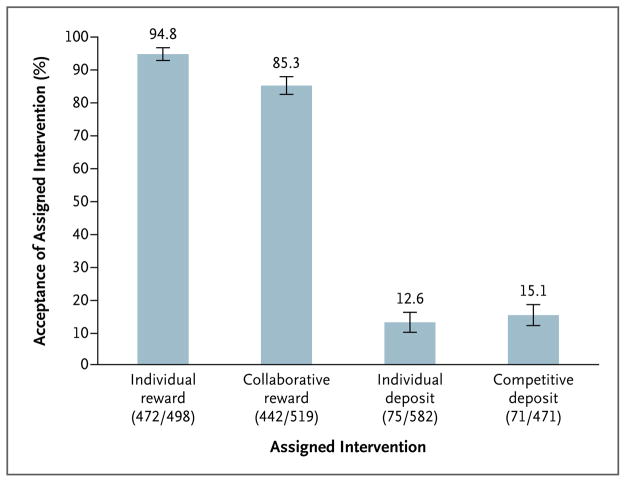

Of 2070 participants assigned to one of the four intervention groups, 1060 (51.2%) accepted that intervention. Participants were much more likely to accept the two reward-based incentive programs (combined acceptance rate, 90.0%) than the two deposit-based programs (combined acceptance rate, 13.7%) (P<0.001) (Fig. 2). Participants were similarly likely to accept the individual incentives (combined acceptance rate, 50.6%) and the group incentives (combined acceptance rate, 51.9%) (P=0.55).

Figure 2. Acceptance Rates of Financial-Incentive Structures.

Acceptance rates were adjusted for two stratifying variables30: whether participants received their health insurance through CVS Caremark and whether their annual household income was at least $60,000 or less than $60,000. I bars denote 95% confidence intervals. In parentheses, the numerator indicates the number of participants accepting each intervention, and the denominator indicates the number of participants assigned to each intervention. The usual-care group is not shown, because there was no option to decline usual care.

EFFECTIVENESS AND COSTS OF INTERVENTIONS

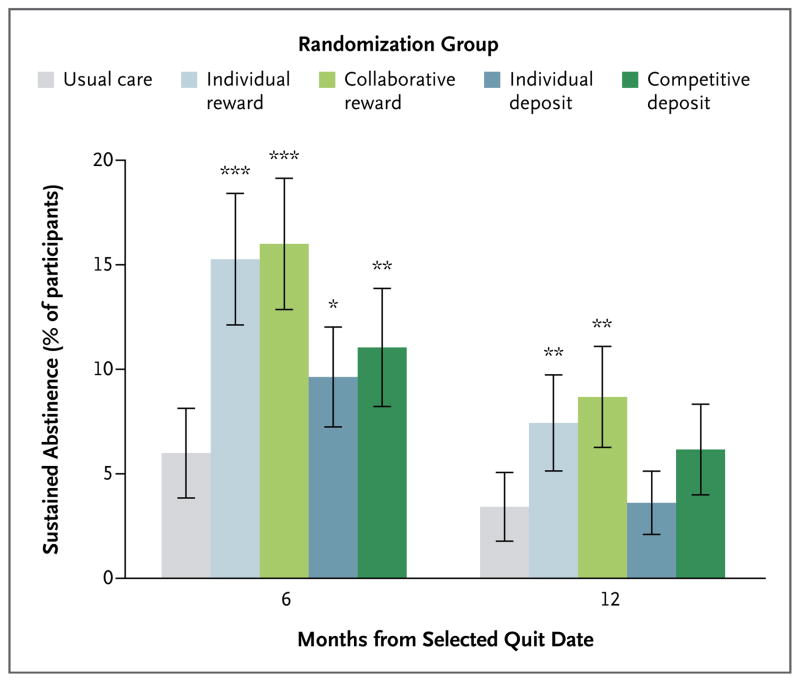

Median payouts to participants who stopped smoking in the four incentive groups were similar (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). In intention-to-treat analyses, all four programs yielded greater rates of sustained abstinence from smoking through 6 months (range, 9.4 to 16.0%) than did usual care (6.0%) (P<0.05 for all comparisons) (Fig. 3, and Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). At 12 months (6 months after the cessation of incentives), roughly half the participants who were abstinent through 6 months in all groups submitted negative cotinine assays, and only the reward-based incentive programs remained superior to usual care (Fig. 3). The proportion of self-reported quitters who submitted a cotinine sample was lower at 12 months than at 30 days or 6 months in all groups (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). In secondary analyses of self-reported abstinence at 12 months, relapsed smoking was much less common than in analyses requiring biochemical confirmation, and all incentive groups remained superior to usual care (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Figure 3. Rates of Sustained Abstinence from Smoking at 6 and 12 Months after Target Quit Date.

The primary outcome was sustained abstinence through 6 months. Asterisks indicate P values (* for P<0.05, ** for P<0.01, and *** for P<0.001) for the comparison of the four intervention groups to usual care, with adjustment for the two stratifying variables30: whether participants received their health insurance through CVS Caremark and whether their annual household income was at least $60,000 or less than $60,000. I bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

At 6 months, the proportion of participants with sustained abstinence was greater with reward-based incentives (15.7%) than with deposit-based incentives (10.2%) (P<0.001) (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix) and was similar between participants assigned to individual-incentive programs and those assigned to group-incentive programs (12.1% vs. 13.7%, P = 0.29) (Table S5 in the Supplementary Appendix). Participants with access to free pharmacologic cessation aids through their CVS Caremark benefits did not have higher abstinence rates than participants without such benefits (Table S6 in the Supplementary Appendix). Total costs spent per participant who had sustained abstinence were lower in the deposit-based groups than in the reward-based groups (Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

EFFICACY OF INTERVENTIONS

Given the similar effectiveness of individual rewards and collaborative rewards and of individual deposits and competitive deposits, we grouped the reward-based incentives as well as the deposit-based incentives for efficacy analyses. In standard per-protocol analyses, 52.3% of those who accepted deposits versus 17.1% of those who accepted rewards had sustained abstinence through 6 months (P<0.001), and similarly large differences were observed at all time points (Table S7 in the Supplementary Appendix). In analyses of the complier average treatment effect, which adjust for the selection effects inherent in per-protocol analyses, the rate of abstinence at 6 months was 13.2 percentage points (95% confidence interval, 3.1 to 22.8) higher in the deposit-based programs than in the reward-based programs among the 13.7% of smokers who would accept either type of incentive (Table 2). According to this approach, deposits were superior to rewards even if we assumed that participants who would accept deposits had up to 12.5 times greater underlying propensities to stop smoking than participants who would accept rewards only.

Table 2.

Analysis of the Complier Average Treatment Effect of Sustained Abstinence from Smoking at 6 Months.*

| Comparison of Efficacy | Absolute Difference in Rate of Sustained Abstinence percentage points (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Reward-based incentives vs. usual care among participants who would accept reward incentive | 10.7 (6.8 to 14.7) |

| Deposit-based incentives vs. usual care among participants who would accept deposit incentive | 30.8 (11.0 to 50.6) |

| Deposit-based incentives† vs. reward-based incentives among participants who would accept either type of incentive, with the assumption that the underlying odds of quitting among participants who would accept deposits are greater than the odds of quitting among participants who would only accept rewards by a factor of | |

| 2.71, the lower boundary of the 95% CI of the best estimate | 25.8 (16.2 to 34.8) |

| 9.36, the best estimate | 13.2 (3.1 to 22.8) |

| 23.12, the upper boundary of the 95% CI of the best estimate | 6.4 (−5.7 to 17.4) |

A detailed explanation of this analysis is provided in the Supplementary Appendix. In brief, this method uses the randomization group as an instrumental variable, thereby providing estimates of the efficacy of interventions among people who accept them. Unlike traditional per-protocol analyses, this approach uses data on all randomly assigned participants and adjusts estimates of efficacy for the selection biases that may arise if participants’ decisions to accept or decline their assigned interventions are related to their underlying odds of smoking cessation.34–36 This analysis assumes that participants who would accept deposits would have also accepted rewards if rewards had instead been offered. Estimates are on the additive scale; thus, absolute risk differences are shown with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The efficacy of deposit contracts is statistically superior to the efficacy of rewards as long as the underlying odds of quitting among participants who accept deposits are no more than 12.5 times greater than the odds of quitting among participants who would only accept rewards.

ANALYSES ACCOUNTING FOR ENROLLMENT OF POTENTIAL NONSMOKERS

Among 150 participants asked to submit a cotinine assay at baseline to confirm smoking status, 9 (6.0%) submitted negative assays and 21 (14.0%) did not return assays. These rates were similar across groups (Table S8 in the Supplementary Appendix), and sensitivity analyses adjusting for the possibility that up to 20% of the participants were not smokers revealed nearly identical estimates of effectiveness (Table S9 in the Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

More than 50 years after the release of the first Surgeon General’s report on the harmful effects of smoking, national policies, behavioral programs, and pharmacologic approaches have helped reduce smoking rates in the United States.37 However, the need for new approaches is clear because smoking remains the leading cause of preventable illness and death.38,39

In this large randomized trial across the United States, we found that four different incentive programs with expected values of $800 were each effective in promoting sustained abstinence from smoking. Perhaps the most important finding is that incentive programs that required people to deposit $150 of their own money were less effective overall than reward-based programs of similar value because few people accepted such deposit programs. This was true despite the $650 reward offered to deposit-arm participants in addition to the return of their original $150 deposits. However, analyses that account for the different acceptance rates of the interventions showed that deposit-based incentives were substantially more efficacious than reward-based incentives among people who would have accepted either. The robustness of this result to reasonably large potential selection effects suggests that incentives that build on participants’ loss aversion13 may meaningfully change behavior.

Second, we found that group-oriented reward programs were not significantly more effective than individual-oriented programs. The results of this large trial are therefore consistent with those of small randomized, controlled trials of incentives for weight loss in which group-oriented payments, as compared with individual-oriented payments, produced small early benefits that were not sustained over time.19,22

Finally, the finding that individual rewards of $800, as compared with usual care, nearly tripled the rate of smoking cessation among CVS Caremark employees and their friends and family confirms and extends the generalizability of our finding from a previous trial involving General Electric employees.8 In addition to the public health effects of such smoking reductions, these findings are important for employers. Because employing a smoker is estimated to cost $5,816 more each year than employing a non-smoker,40 even an $800 payment borne entirely by employers and paid only to those who quit would be highly cost-saving.

This study has limitations. First, the low rate of acceptance of the deposit programs required protocol modifications to restrict the proportions of participants who would be randomly assigned to those groups. Implementing these limitations preserved balance in participant characteristics across groups and preserved power for all effectiveness analyses but limited the precision of analyses comparing the efficacy of reward and deposit groups. Second, only 41% of the participants had access to free pharmacologic and behavioral cessation aids through their employee benefits. However, smoking-cessation rates were not higher among those with access to such aids, a finding that suggests that the superiority of incentives would hold in populations with universal access. Third, in all trial groups, nearly half the smokers who quit at the end of the intervention at 6 months did not document sustained abstinence through 12 months. This suggests similar durability of financial incentives to nicotine-replacement therapy and bupropion, for which relapse after completion of treatment has also occurred in roughly 50% of the participants.41,42 Secondary analyses suggest that the true relapse rates in our trial may have been lower, given the reduction in submission of any samples at 12 months across groups (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix).

This study also has several strengths. In addition to comparing financial incentives for smoking cessation in a large number of participants, the trial measured the specific contributions of acceptance and efficacy of the interventions to their overall effectiveness. This trial also compared multiple incentive programs with design features based on behavioral economic theory, including repeated payments to reinforce target behaviors,43 bonus payments at the end of the intervention to offset smokers’ tendencies to discount the importance of future events,44,45 and the provision of ongoing feedback regarding participants’ accrued gains and losses contingent on their self-reported smoking status to maximize the effect of regret aversion.20,21 Finally, this trial randomly selected participants for screening cotinine tests to prevent nonsmokers from enrolling. The robustness of our findings in analyses accounting for potential participation of nonsmokers provides strong evidence regarding the effectiveness of incentives.

In summary, this trial shows that among several financial-incentive programs for smoking cessation, rewards for smoking cessation are more effective overall than are deposit-based contracts owing to their much higher rate of acceptance. In addition, the efficacy of deposit-based contracts among those who use them and the cost-effectiveness of such contracts for employers suggest that future innovations in employee benefit design should seek to establish the effectiveness of smoking-cessation programs requiring deposits smaller than the $150 used in this trial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA159932, to Dr. Halpern), a grant from the National Institute on Aging (RC2 AG036592, to Drs. Asch and Volpp), and CVS Caremark.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg FE, Donham R, Badger GJ. Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:568–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane RL, Johnson PE, Town RJ, Butler M. A structured review of the effect of economic incentives on consumers’ preventive behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:327–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volpp KG, John LK, Troxel AB, Norton L, Fassbender J, Loewenstein G. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2631–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volpp KG, Loewenstein G, Troxel AB, et al. A test of financial incentives to improve warfarin adherence. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:272. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giuffrida A, Torgerson DJ. Should we pay the patient? Review of financial incentives to enhance patient compliance. BMJ. 1997;315:703–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7110.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutherland K, Christianson JB, Leatherman S. Impact of targeted financial incentives on personal health behavior: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(Suppl):36S–78S. doi: 10.1177/1077558708324235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volpp KG, Galvin R. Reward-based incentives for smoking cessation: how a carrot became a stick. JAMA. 2014;311:909–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strickland S. Does it work to pay people to live healthier lives? BMJ. 2014;348:g2458. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Towers Watson National Business Group on Health. Employer survey on purchasing value in health care. 2014 ( http://www.towerswatson.com/en-US/Insights/IC-Types/Survey-Research-Results/2014/05/full-report-towers-watson-nbgh-2013-2014-employer-survey-on-purchasing-value-in-health-care)

- 12.Volpp KG, Pauly MV, Loewenstein G, Bangsberg D. P4P4P: an agenda for research on pay-for-performance for patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:206–14. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263–91. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halpern SD, Asch DA, Volpp KG. Commitment contracts as a way to health. BMJ. 2012;344:e522. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers T, Milkman KL, Volpp KG. Commitment devices: using initiatives to change behavior. JAMA. 2014;311:2065–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2249–58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watts DJ, Strogatz SH. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature. 1998;393:440–2. doi: 10.1038/30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul-Ebhonhimhen V, Avenell A. A systematic review of the effectiveness of group versus individual treatments for adult obesity. Obes Facts. 2009;2:17–24. doi: 10.1159/000186144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeffery RW, Gerber WM, Rosenthal BS, Lindquist RA. Monetary contracts in weight control: effectiveness of group and individual contracts of varying size. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:242–8. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connolly T, Butler DU. Regret in economic and psychological theories of choice. J Behav Decis Mak. 2006;19:148–58. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoelzl E, Loewenstein G. Wearing out your shoes to prevent someone else from stepping into them: anticipated regret and social takeover in sequential decisions. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2005;98:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kullgren JT, Troxel AB, Loewenstein G, et al. Individual-versus group-based financial incentives for weight loss: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:505–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu FF, Zhang LX, He XM. Efficient randomized-adaptive designs. Ann Statist. 2009;37:2543–60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dragalin V. Adaptive designs: terminology and classification. Drug Inf J. 2006;40:425–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown CH, Ten Have TR, Jo B, et al. Adaptive designs for randomized trials in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.French B, Small DS, Novak J, et al. Preference-adaptive randomization in comparative effectiveness studies. Trials. 2015;16:99. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0592-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benowitz NL, Ahijevch K, Hall S, et al. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:149–59. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacob P, III, Hatsukami D, Severson H, Hall S, Yu L, Benowitz NL. Anabasine and anatabine as biomarkers for tobacco use during nicotine replacement therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1668–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahan BC, Morris TP. Improper analysis of trials randomised using stratified blocks or minimisation. Stat Med. 2012;31:328–40. doi: 10.1002/sim.4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sommer A, Zeger SL. On estimating efficacy from clinical trials. Stat Med. 1991;10:45–52. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newhouse JP, McClellan M. Econometrics in outcomes research: the use of instrumental variables. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:17–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Angrist JD, Imbens GW, Rubin DB. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91:444–55. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sussman JB, Hayward RA. An IV for the RCT: using instrumental variables to adjust for treatment contamination in randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c2073. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng J, Small D. Bounds on causal effects in three-arm trials with noncompliance. J R Stat Soc B. 2006;68:815–36. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng J, Small D, Tan Z, Ten Have T. Efficient nonparametric estimation of causal effects in randomized trials with noncompliance. Biometrika. 2009;96:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 37.The health consequences of smoking — 50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. ( http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rostron BL, Chang CM, Pechacek TF. Estimation of cigarette smoking-attributable morbidity in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1922–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):e1000058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berman M, Crane R, Seiber E, Munur M. Estimating the cost of a smoking employee. Tob Control. 2014;23:428–33. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, et al. A controlled trial of sustained-release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:685–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnoll RA, Patterson F, Wileyto EP, et al. Effectiveness of extended-duration transdermal nicotine therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:144–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-3-201002020-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes, and they will come: contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:250–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schotter A, Weigelt K. Behavioral consequences of corporate incentives and long-term bonuses — an experimental study. Manage Sci. 1992;38:1280–98. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Epstein LH, Cuevas J, Rodgers K, Wileyto EP. Does delay discounting play an etiological role in smoking or is it a consequence of smoking? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.