Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To estimate the prevalence of urinary tract infection in infants and children with bronchiolitis.

METHODS:

A retrospective cross-sectional study involving patients zero to 24 months of age who were hospitalized with acute bronchiolitis was conducted.

RESULTS:

A total of 835 paediatric patients with acute bronchiolitis were admitted to the paediatric ward between January 2010 and December 2012. The mean (± SD) age at diagnosis was 3.47±2.99 months. There were 325 (39%) girls and 510 (61%) boys. For the purpose of data analysis, the patient population was divided into three groups: group 1 included children hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis; group 2 included children hospitalized with clinical bronchiolitis with no virus detected; and group 3 included children hospitalized with clinical bronchiolitis due to a respiratory virus other than RSV. Results revealed that urinary tract infection was present in 10% of patients, and was most common in group 3 (13.4%) followed by group 2 (9.7%), and was least common in group 1 (6%) (P=0.030).

CONCLUSIONS:

The possibility of a urinary tract infection should be considered in a febrile child with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis, particularly if the trigger is a respiratory virus other than RSV.

Keywords: Bronchiolitis, Infection, Urine

Abstract

OBJECTIF :

Évaluer la prévalence d’infections urinaires chez les nourrissons atteints de bronchiolite.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont effectué une étude transversale rétrospective auprès de patients de zéro à 24 mois hospitalisés en raison d’une bronchiolite aiguë.

RÉSULTATS :

Au total, 835 patients d’âge pédiatrique atteints de bronchiolite aiguë ont été hospitalisés dans l’aile pédiatrique entre janvier 2010 et décembre 2012. D’un âge moyen (± ÉT) de 3,47±2,99 mois au diagnostic, ils étaient répartis entre 325 filles (39 %) et 510 garçons (61 %). Pour les besoins de l’analyse de données, la population de patients était divisée entre trois groupes : le groupe 1 se composait de nourrissons hospitalisés en raison d’une bronchiolite à virus syncytial respiratoire (VRS), le groupe 2, de nourrissons hospitalisés en raison d’une bronchiolite clinique sans qu’un virus soit décelé et le groupe 3, de nourrissons hospitalisés en raison d’une bronchiolite clinique causée par un autre virus respiratoire que le VRS. Les résultats ont révélé une infection urinaire chez 10 % des patients, plus courante dans le groupe 3 (13,4 %), puis le groupe 2 (9,7 %), et moins courante dans le groupe 1 (6 %) (P=0,030).

CONCLUSIONS :

Il faut envisager la possibilité d’infection urinaire chez un nourrisson fébrile atteint d’une bronchiolite diagnostiquée, particulièrement si elle est déclenchée par un autre virus respiratoire que le VRS.

Viral bronchiolitis is the most common source of lower respiratory tract infection in infants, constituting almost 20% of all-cause infant hospitalizations (1,2). The disease is most common in the fall and winter months, with peak incidence occurring in children between two and six months of age (3,4).

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) defines bronchiolitis as “a constellation of clinical symptoms and signs including a viral upper respiratory prodrome followed by increased respiratory effort and wheezing in children less than two years of age” (5).

Adjuvant serious bacterial infection (SBI) in children with acute bronchiolitis is always a concern expressed by clinicians (6). It has been reported that the incidence of acute bronchiolitis coexisting with SBI is low, with the majority being urinary tract infections (1% to 7.5%) (6–11). Meanwhile, the overall prevalence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in the general paediatric population is nearly 7% among infants and children two to 24 months of age, and approximately 8% in children two to 19 years of age (12). An accurate initial diagnosis of UTI is important because young infants are at risk for renal scarring and concomitant bacteremia (11).

The AAP Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection suggested that to optimize the diagnosis of UTI, “clinicians should require both urinalysis results that suggest infection (pyuria and/or bacteriuria) and the presence of ≥50,000 colony-forming units (CFUs) per millilitre of a uropathogen cultured from a urine specimen obtained through catheterization or suprapubic aspirate” (13). The finding of ≥10 white blood cells (WBCs) per microlitre in an uncentrifuged urine sample has been reported to be a sensitive indicator of UTI (13,14). The sensitivity and specificity of pyuria for the diagnosis of UTI in children are 73% and 81%, respectively. Moreover, expert opinions state that the absence of pyuria does not rule out the diagnosis of UTI, specifically in infants <2 months of age (14).

The majority of studies investigating bronchiolitis have concentrated on respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) disease and its associated risk factors (3,15,16). However, trends in hospitalization rates, epidemiology or disease severity of bronchiolitis caused by other viruses remain to be fully defined and investigated.

The aims of the present study were to estimate the prevalence of UTI in infants and children with bronchiolitis, and to evaluate the effect of demographic and clinical characteristics and viral etiology on the prevalence rates of UTI.

METHODS

A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted at Hamad Medical Corporation (Doha, Qatar), the only tertiary medical institution in the State of Qatar. Patients zero to 24 months of age hospitalized with acute bronchiolitis between January 2010 and December 2012 were included in the present study. The patient population was identified by an advanced search of the institution’s medical records database using the specific International Classification of Diseases – Ninth Revision code for bronchiolitis. The search was refined to include only patients ≤2 years of age. All infants and young children with urinary tract abnormalities and those with rectal temperatures ≤38°C (100°F) (17) were subsequently excluded.

The following data were collected: age at diagnosis; gestational age; sex; urine microscopy and urine culture results; and respiratory virus real-time polymerase chain reaction (RVRT-PCR) results.

RVRT-PCR for common respiratory viral antigens was performed by collecting a small amount of fluid/mucous from nasal secretion. The molecular biology laboratory in the authors’ hospital conducts an identification panel for every requested nasal secretion sample for the following viruses: influenza virus A and B, parainfluenza virus types 1–4, coronavirus, rhinovirus, bocavirus, enterovirus, parechovirus, human metapneumovirus, adenovirus, novel coronavirus and pandemic influenza A H1N1.

For the purpose of data analysis, the patient population, regardless of the urine culture results, was divided into three groups: group 1 included children hospitalized with RSV bronchiolitis; group 2 included children hospitalized with clinical bronchiolitis with no virus detected; and group 3 included children hospitalized with clinical bronchiolitis due to a respiratory virus other than RSV.

The diagnosis of bronchiolitis was based on the AAP definition (5). The AAP guidelines are followed in the authors’ institution, and participants met the criteria of bronchiolitis as documented in the patients’ charts.

Urine cultures are routinely performed in febrile infants with bronchiolitis in the authors’ emergency department before admission to the paediatric ward. Only catheter urine samples were included to decrease the risk of contaminated urine. Significant pyuria was considered to be ≥10 WBC/μL in uncentrifuged urine samples, based on evidence-based literature (13,14).

Urine culture results were monitored for two days until their completion, and UTI was diagnosed if there were >100,000 colonies of a single organism per millilitre (≥100×106 CFU/L) and significant pyuria. The authors’ institutional laboratory only reports growth of urine culture in the following categories: 103 to 104 CFU/mL, 104 to 105 CFU/mL and >105 CFU/mL (≥100×106 CFU/L). Antibiotic treatment was started for all children with positive urine cultures.

Approval for the study was obtained from Hamad Medical Corporation – Ethics Committee (Ref # 13139/13).

Statistical analysis

Qualitative and quantitative data values were expressed as frequency and percentage, and mean ± SD with median and range. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and all other clinical characteristics of the participants. The primary outcome variable (the prevalence of UTI in infants and children with bronchiolitis) was estimated and presented with 95% CI. Associations between ≥2 qualitative variables were analyzed using the χ2 test. For small cell frequencies, the χ2 test with continuity correction factor or Fisher’s exact test was applied. For quantitative variables, means between two and >2 independent groups were analyzed using unpaired t tests and one-way ANOVAs. When an overall group difference was found to be statistically significant, pair-wise comparisons were made using the Bonferroni multiple comparison test. The results were presented with the associated 95% CI. The Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were applied for non-normal or skewed data. Relationships between two quantitative variables were examined using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis were applied to assess the associations of various potential predictors and covariates, such as sex, age at diagnosis, gestational age and RSV RVRT-PCR, with the outcome variable (ie, UTI). Results of the logistic regression analyses are presented as ORs and 95% CIs. Pictorial presentations of the key results were produced using appropriate statistical graphs. A two-sided P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 (IBM Corporation, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 857 patients ≤2 years of age were identified in the medical records. Fifteen patients with hydronephrosis were excluded, as were seven patients with other congenital anomalies of the urinary tract including renal agenesis and duplicating collecting system. A total of 835 patients met the initial inclusion criteria for clinical bronchiolitis with no urinary tract abnormalities. All children were febrile in the emergency department according to documentation in the patients’ charts. The mean age at diagnosis was 3.47±2.99 months. The sample included 325 (39%) girls and 510 (61%) boys. The mean gestational age was 37.01±3.37 weeks (range 25 to 42 weeks), with 142 (17.1%) born before 35 weeks’ gestation. RVRT-PCR testing was obtained in 92% (n=769) of cases. RVRT-PCR was not conducted on 66 patients for the following reasons: parents refusal; technical flaws when obtaining the sample; or because the laboratory does not process RVRT-PCR samples on the weekends. RSV was identified in 352 (45.7%) patients; respiratory viruses other than RSV were found in 275 (35.7%) patients and 142 (18.4%) were tested but had no viruses detected. Non-RSV viruses included rhinovirus (n=85 [31%]), parainfluenza virus type 4 (n=40 [14%]), adenovirus (n=40 [14%]), HMPV (n=27 [10%]), bocavirus (n=27 [10%]), coronavirus (n=20 [7%]), parainfluenza virus type 1 (n=9 [3.4%]), parainfluenza virus type 2 (n=9 [3.4%]), parainfluenza virus type 3 (n=9 [3.4%]) and H1N1 (n=9 [3.4%]).

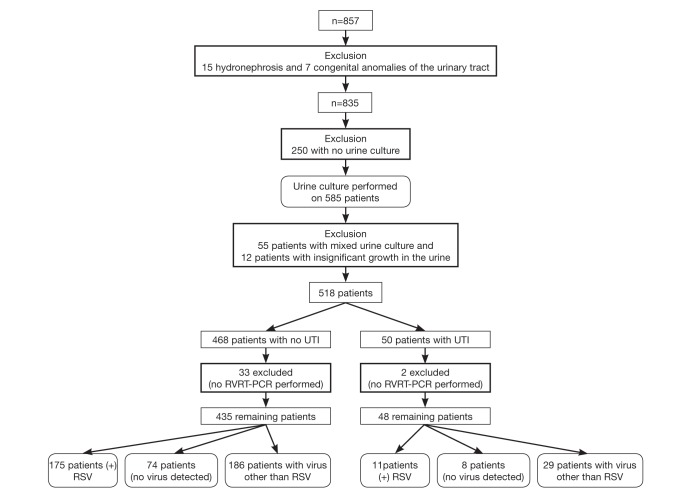

Of the 835 patients, catheterization was not conducted on 250 patients, either due to parents’ refusal or technical flaws when obtaining the sample. An additional 55 patients were excluded because the urine culture revealed mixed growth, and 12 patients were excluded because the urine sample grew ≤105 CFU/mL (≤100×106 CFU/L). For the remaining 518 patients, 468 (288 boys and 180 girls) had negative urine cultures and 50 (23 boys and 27 girls) had positive urine cultures, and significant pyuria. Two of the 50 patients who had a UTI were excluded because RVRT-PCR was not conducted (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Patients with bronchiolitis and urinary tract infection (UTI). RSV Respiratory syncytial virus; RVRT-PCR Respiratory virus real-time polymerase chain reaction

The mean age of group 3 (non-RSV viruses) at diagnosis was significantly higher (4.17±3.86 months) compared with group 1 (RSV) (3.43±3.63 months) and group 2 (no virus detected) (2.95±2.36 months), respectively (P=0.002). In contrast, the gestational age was found to be significantly higher among group 1 participants (37.64±2.58 weeks) compared with group 2 (36.38±3.65 weeks) and group 3 (36.22±4.11 weeks), respectively (P=0.006).

The overall prevalence of UTI in all groups was 10% (48 of 483) of cases (95% CI 7.6% to 12.9%). The prevalence of UTI was significantly higher in group 3 (29 of 215 [13.4%]) compared with group 1 (11 of 186 [6%]) and group 2 (eight of 82 [9.7%]); P=0.030.

A significantly higher prevalence of UTI was observed in girls compared with boys (13.5% [95% CI 9.5% to 18.8%] versus 7.4% [95% CI 5.1% to 10.9%]; P=0.023). Age at diagnosis >2 months was significantly associated with a higher prevalence of UTI compared with age ≤2 months (14.1% [95% CI 10.2% to 19.1%] versus 6.4% [95% CI 4.1% to 10.1%]; P=0.005).

Logistic regression analysis testing for each predictive variable and its association with UTI was conducted and the results presented as ORs and associated 95% CIs. Being female (OR 1.94 [95% CI 1.09 to 3.49]); P=0.025), older age at diagnosis (OR 2.41 [95% CI 1.29 to 4.51]; P=0.006) and in group 3 (OR= 2.57 [95% CI 1.25 to 5.28]; P=0.010) were significantly associated with an increased risk for UTI. In multivariable logistic regression analysis controlling for all potential covariates, such as sex, age at diagnosis, gestational age and RVRT-PCR, older age at diagnosis (adjusted OR 3.65 [95% CI 1.58 to 8.42]; P=0.002) remained significantly associated with UTI.

DISCUSSION

The present study found that UTIs were present in 10% of children zero to 24 months of age hospitalized with acute bronchiolitis. UTIs were most common in children with a confirmed diagnosis of bronchiolitis caused by a virus other than RSV followed by bronchiolitis caused by an unidentified agent; UTIs were least common in children with bronchiolitis caused by RSV.

In a systematic review, Ralston et al (6) outlined the risk for occult SBI in young febrile infants presenting with either “proven RSV infection” or “clinical bronchiolitis”. Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria. Of the 11 studies (7–10,18–24), five were prospective (8,19,21–22,24) and six were retrospective (7,9,10,18,20,23). The population included infants <90 days of age. In nine studies (7–10,18,19,21,22,24), all of the included participants were febrile (≥38°C) and in two studies the percentage of febrile infants was 72.5% to 75% (20,23). A random-effects meta-analysis of UTI rates was conducted. Subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the effects of the study setting (inpatient versus emergency department), study design (prospective versus retrospective) and inclusion criteria (“proven RSV infection” or “clinical bronchiolitis”) on the percentage of UTIs in the included studies. The authors concluded that the average rate of UTIs in infants in the 11 studies was 3.3% (95% CI 1.9% to 5.7%). The overall average rate of UTI in group 1 of the present study (proven RSV) was comparable with the upper limit result of the study conducted by Raslton et al (6) (6% versus 5.7%). However, the overall incidence of UTI in all cases of bronchiolitis in our study was higher (10%). Moreover, the age of the populations of all the studies summarized by Ralston et al (6) was younger compared with our participants (<90 days versus 3.47±2.99 months). We believe that the age difference and the percentage of febrile children may have played a role in the difference in UTI rates between the meta-analysis study conducted by Ralston et al (6) and our investigation.

Other authors have investigated the effect of respiratory viruses other than RSV on the risk of acquiring SBI, including UTI. For example, Rittichier et al (25) reported that febrile infants with enterovirus had a coexisting rate of SBI of 6.6%, with the majority being UTIs. Meanwhile, Smitherman et al (26) studied the risk of SBI in febrile infants with documented influenza infections in 705 febrile infants. The study concluded that bacteremia was present in 0.6% and UTI in 1.8% of infants with influenza virus infections, compared with a 4.2% rate of bacteremia and 9.9% rate of UTI in the infants who tested negative for the influenza virus.

The suggested mechanism by which influenza can lead to bacterial infection is viral destruction of respiratory epithelium, then immunosuppression followed by bacterial adhesion, resulting in secondary bacterial invasion (27). However, the mechanism by which a virus can induce UTIs are not yet known.

The present study has some limitations. For instance, RVRTPCR is not 100% sensitive (28); therefore, we may not have identified all respiratory viruses triggering bronchiolitis. In addition, we only included urine cultures ≥100,000 CFU/mL (100×106 CFU/L); thus, we may have underestimated the rate of UTI in children whose urine sample grew 50×106 CFU/L to 100×106 CFU/L. Moreover, despite implementing the strict definition of UTI and the aseptic techniques used to obtain the urine samples, we could not rule out the unlikely possibility that children with contaminated urine or asymptomatic bacteriuria could have been labelled as having UTI. Furthermore, there is a possibility that some of the infants could have been already on antibiotics before coming to the emergency department and, therefore, were not diagnosed although they may have had a UTI. Because the present study was retrospective, possible causes of error, bias and confounding could not be completely documented and addressed. The lack of a control group without bronchiolitis limits the ability to detect and observe meaningful differences in UTI between bronchiolitis and nonbronchiolitis groups. A larger prospective study is needed to address the above limitations and demonstrate generalizability of the findings in this area.

CONCLUSION

The possibility of a UTI should be considered in a febrile child with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis, particularly if the trigger is a respiratory virus other than RSV.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Medical Research Center at Hamad Medical Corporation in Qatar for the ethical approval to conduct this study.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding this work.

FUNDING SOURCE: No funds were provided to conduct the study. However, the Medical Research Center at Hamad Medical Corporation provided funds (US$ 6,850) to cover publication fees as well as abstract presentation if required.

CONTRIBUTORS’ STATEMENT: Mohamed A Hendaus: Dr Hendaus conceptualized and designed the study, assisted in data collection, analyzed the data, drafted the initial manuscript, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Ahmed H Al-Hammadi: Dr Al-Hammadi assisted in conceptualizing and designing the study, revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Mohamed S Khalifa: Dr Khalifa assisted in designing and collecting the data, assisted in reference search and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Eshan Muneer: Dr Muneer assisted in designing and collecting the data, assisted in reference search and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Prem Chandra: Dr Chandra assisted in data analysis and in writing the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Dr Hendaus wrote the first draft of the manuscript and no honorarium, grant, or other form of payment was given to anyone to produce the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yorita KL, Holman RC, Sejvar JJ, Steiner CA, Schonberger LB. Infectious disease hospitalizations among infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2008;121:244–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:588–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shay DK, Holman RC, Newman RD, Liu LL, Stout JW, Anderson LJ. Bronchiolitis-associated hospitalizations among US children, 1980–1996. JAMA. 1999;282:1440–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansbach JM, Pelletier AJ, Camargo CA., Jr US outpatient office visits for bronchiolitis, 1993–2004. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:304–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Pediatrics, Subcommittee on Diagnosis and Management of Bronchiolitis Pediatrics. 2006;118:1774–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ralston S, Hill V, Waters A. Occult serious bacterial infection in infants younger than 60 to 90 days with bronchiolitis: A systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:951–6. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melendez E, Harper MB. Utility of sepsis evaluation in infants 90 days of age or younger with fever and clinical bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:1053–6. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000101296.68993.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine DA, Platt SL, Dayan PS, et al. Multicenter RSV-SBI Study Group of the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics Risk of serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants with respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1728–34. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purcell K, Fergie J. Concurrent serious bacterial infections in 2396 infants and children hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infections. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:322–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Titus MO, Wright SW. Prevalence of serious bacterial infections in febrile infants with respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics. 2003;112:282–4. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zorc JJ, Levine DA, Platt SL, et al. Multicenter RSV-SBI Study Group of the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical and demographic factors associated with urinary tract infection in young febrile infants. Pediatrics. 2005;116:644–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaikh N, Morone NE, Bost JE, Farrell MH. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in childhood: A meta-analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:302–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31815e4122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Pediatrics, Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Roberts KB. Urinary tract infection: Clincal practice guideline for diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics. 2011;128:595–610. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson JL, Finlay JC, Lang ME, Bortolussi R, Canadian Paediatric Society. Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee. Community Paediatrics Committee Urinary tract infections in infants and children: Diagnosis and management. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19:315–25. doi: 10.1093/pch/19.6.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leader S, Kohlhase K. Respiratory syncytial virus-coded pediatric hospitalizations, 1997 to 1999. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:629–32. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200207000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leader S, Kohlhase K. Recent trends in severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) among US infants, 1997 to 2000. J Pediatr. 2003;143(5 Suppl):S127–S132. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00510-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canadian Paediatric Society Community Paediatrics Committee Temperature measurement in paediatrics <www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/temperature-measurement>(Accessed January 1, 2014)

- 18.Oray-Schrom P, Phoenix C, St Martin D, Amoateng-Adjepong Y. Sepsis workup in febrile infants 0–90 days of age with respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19:314–9. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000092576.40174.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byington CL, Enriquez FR, Hoff C, et al. Serious bacterial infections in febrile infants 1 to 90 days old with and without viral infections. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1662–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antonow JA, Hansen K, McKinstry CA, Byington CL. Sepsis evaluations in hospitalized infants with bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:231–6. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199803000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bilavsky E, Shouval DS, Yarden-Bilavsky H, Fisch N, Ashkenazi S, Amir J. A prospective study of the risk for serious bacterial infections in hospitalized febrile infants with or without bronchiolitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:269–70. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31815e85b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuppermann N, Bank DE, Walton EA, Senac MO, Jr, McCaslin I. Risks for bacteremia and urinary tract infections in young febrile children with bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:1207–14. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170490033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liebelt EL, Qi K, Harvey K. Diagnostic testing for serious bacterial infections in infants aged 90 days or younger with bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:525–30. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luginbuhl LM, Newman TB, Pantell RH, Finch SA, Wasserman RC. Office-based treatment and outcomes for febrile infants with clinically diagnosed bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2008;122:947–54. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rittichier KR, Bryan PA, Bassett KE, et al. Diagnosis and outcomes of enterovirus infections in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:546–50. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000164810.60080.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smitherman HF, Caviness AC, Macias CG. Retrospective review of serious bacterial infections in infants who are 0 to 36 months of age and have influenza A infection. Pediatrics. 2005;115:710–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peltola VT, McCullers JA. Respiratory viruses predisposing to bacterial infections: Role of neuraminidase. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S87–S97. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000108197.81270.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng J, Ma Z, Huang W, et al. Respiratory virus multiplex RT-PCR assay sensitivities and influence factors in hospitalized children with lower respiratory tract infections. Virol Sin. 2013;28:97–102. doi: 10.1007/s12250-013-3312-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]