Abstract

Background

Faunal resources have played an extensive range of roles in human life from the initial days of recorded history. In addition to their importance, animals have been acknowledged in religion, art, music and literature and several other different cultural manifestations of mankind. Human beings are acquainted with use of animals for foodstuff, cloth, medicine, etc. since ancient times. Huge work has been carried out on ethnobotany and traditional medicine. Animal and their products are also holding medicinal properties that can be exploited for the benefit of human beings like plants. In Tanzania, many tribal communities are spread all over the country and these people are still totally depended on local customary medicinal system for their health care. In the world Tanzania is gifted with wide range of floral and faunal biodiversity. The use of traditional medicine from animals by Sukuma ethnic group of Busega district is the aim of the present study.

Method

In order to collect the information on ethnozoological use about animal and their products predominant among this tribe in Busega district, a study was carried out from August 2012, to July 2013. Data were collected through semi-structured questionnaire and open interview with 180 (118 male and 62 females) selected people. The people from whom the data were collected comprise old age community members, traditional health practicener, fishermen and cultural officers. The name of animal and other ethnozoological information were documented. Pictures and discussion were also recorded with the help of camera and voice recorder.

Result

A total of 42 various animal species were used in nearly 30 different medicinal purposes including STD, stoppage of bleeding, reproductive disorders, asthma, weakness, tuberculosis, cough, paralysis and wound and for other religious beliefs. It has been noticed that animal used by Sukuma tribe, comprise of seventeen mammals, seven birds, four reptiles, eight arthropods and two mollusks. Some of the protected species were also used as important medicinal resources. We also found that cough, tuberculosis, asthma and other respiratory diseases are the utmost cited disease, as such, a number of traditional medicines are available for the treatment.

Conclusions

The present work indicates that 42 animal species were being used to treat nearly 30 different ailments and results show that ethnozoological practices are an important alternative medicinal practice by the Sukuma tribe living in Bungesa district. The present study also indicates the very rich ethnozoological knowledge of these people in relation to traditional medicine. So there is a critical need to properly document to keep a record of the ethnozoological information. We hope that the information generated in this study will be useful for further research in the field of ethnozoology, ethnopharmacology and conservation approach.

Keywods: Ethnozoology, Traditional Medicine, Medicinal animals, Tanzania

Background

Faunal resources have played a wide range of roles in human life from the earliest days of recorded history. Human beings are familiar with use of animals and plants for food, cloth, medicine, etc. since ancient times [1,2]. The study of relationship between the human societies and the animal resources around them deals under Ethnozoology [3]. Since prehistoric time’s animals, their parts, and products have created part of the inventory of medicinal substances used in numerous cultures [4]. The world health organization estimates that most of the world’s population relies primarily on animal and plant based medicines [5]. Of the 252 indispensible chemicals that have been selected by the World Health Organization, 8.7% derived from animals [6]. In Brazil, Alves et al. reported the medicinal use of 283 animal species for the treatment of various ailments [7]. In Bahia state, in the northeast of Brazil, over 180 medicinal animals have been recorded in traditional health care practices [8]. In Traditional Chinese Medicine more than 1500 animal species have been recorded to be some medicinal use [9]. Alves and Rosa recorded the use of 97 animal species as traditional medicine in urban areas of NE and N Brazil [10]. Lev and Amar conducted a survey in the selected markets of Israel and found 20 animal species, which products were sold as traditional drugs [11]. Tamang people of Nepal identify the 11 animal species for used in zootherapeutic purposes [12]. Alves and Rosa in the North and north- east regions of Brazil carried out a survey in fishing communities and recorded 138 animal species, used as traditional medicine [13]. Alves et al. also reported nearly 165 reptile’s species were used in traditional folk medicine around the world [14]. Alves conducted a review study in Northeast Brazil and lists 250 animal species for the treatment of diverse ailments [15]. Lev and Amar conducted a study in the selected markets in the kingdom of Jordan and identified 30 animal species, and their products were retailed as traditional medications [16]. In India use of traditional medicine are documented in works like Ayurveda and Charaka Samhita. A number of animals are mentioned in Ayurvedic system, which includes 41 Mammals, 41 Aves, 16 Reptiles, 21 Fishes and 24 Insects [17]. Different ethnic group and tribal people use animals and their products for healing practices of human ailments in present times in India [18]. In Hindu religion people used the various products obtained from the cow viz. milk, urine, dung, curd and ghee since ancient times [19].

Tanzania is gifted with immense faunal and floral biodiversity, because of the thrilling variation in geographical and climatic condition prevailing in the country. In Tanzania, traditional medicine has existed even before colonial times. It used to play a vital role in the doctrine of chiefdoms that existed during pre-colonial era. Colonialists, with their intension to rule Africa had to find a way to discourage all sort of activities which would have provided an opportunity for developing Africans [20]. In Tanzania, different tribal communities are dispersed all over the country, people of these communities are extremely knowledgeable about the animals and their medicinal value, and they also deliver extensive information about the use of animals and their by-products as medicine. Most of the tribal people are totally dependent on local traditional medicinal system for their health care because they are living in very remote areas where hospital and other modern medicinal facilities are not available and even negligible, so they use their traditional knowledge for medicinal purpose and this knowledge is passed through oral communication from generation to generation. It is estimated that more than 80% of the rural population in Tanzania depends on the traditional medicine [21].

A lot of work has been done on utilization of plants and their products as traditional and allopathic medicine in the world. Like plants, animal and their products also keep medicinal properties [22]. Most ethnobiological studies conducted in Tanzania have focused on traditional knowledge of plants and less in animals [23,24]. A little work has been done in Ethnozoology in Tanzania and particularly no work is documented in Sukuma tribe and there is a definite scarcity of ethnobiological knowledge when it comes to animal products. The present study briefly reports an ethnomedicinal/traditional medicinal study among Sukuma tribe in Bugusa district in Tanzania.

Methods

The study area

The intended study was carried out in Busega District at Simiyu region. The Busega district is one of five districts in Simiyu Region of Tanzania, namely, Meatu, Itilima, Bariadi, Maswa and Busega. Busega district is located on the northwestern part of Simiyu Region and shares borders with Magu districts in west, Bariadi districts in south, The southeastern part is covered by the Serengeti game reserve and Bunda district. In north side it bordered with Lake Victoria. As a result, many community members utilize both aquatic and terrestrial organisms as a source of medicine.

Busega district is located between latitude 20 10’ and 20 50’ South and between longitude 330 and 340 East. The district headquarter is in Nyashimo town. The district is divided into thirteen (13) wards and fifty four (54) villages as per Tanzania Population and Housing Census 2012 [25]. Busega district is Tropical in nature with sun overhead of equator on March and October. Temperature is tropical and range between 25°C and 30°C with average annual temperature of 27°C. There are two wet seasons, the long rains from mid-March to early June, during which the precipitation is between 700 mm to 1000 mm and averages 800 mm per annum and short rains from October to December, during which the rainfall is between 400 mm to 500 mm [26]. Figure 1: Map of the study area.

Figure 1.

Map of Simiyu region showing all district under the region including District Busega (Wilaya ya Busega).

The Sukuma tribe

The Sukuma are a patrilineal society; the role of the women being to take care of their husbands and children while men are overseer of the family [27,28]. Young people marry only when they are ready to carry the responsibilities marriage entails. They are initiated into adulthood in a ceremony known as “lhane”. The Sukuma do not practice circumcision as part of initiation, but organize a separate ceremony. The young people involved in “lhane” have to be prepared well. Respected elders of the community tutor the initiates on their roles and responsibilities in the family and the whole community. The initiates have to think, act and participate as adults in all rituals. After “lhane” the initiates are considered adults and cannot be asked to deliver messages anywhere as this is a job for non-initiates [28].

The Sukuma are believed to being very superstitious, and most will seek aid from the “Bafumu”, “Balaguzi” and “Basomboji” locally used to refer as medicine men, diviners and sooth sayers, respectively. The Basukuma have many stories based on their beliefs on death and sufferings. Traditional healers believe that fate is determined by “Shing’wengwe” and “Shishieg’we”, that is ogres and spirits. The ogres are usually shown as being half human, half demon, or as terrible monsters [28]. The economic condition of the Sukuma people is not good. Agriculture, animal husbandry; poultry forming and laboring are source of income. Educational level is also found very low. The life of the people are full of traditions and social customs from birth to death owning to outdated customs, not attuned to remain competitive in the current economic scenario of privatization [Figures 2, 3, 4, 5].

Figure 2.

Sukuma lady doing traditional prayer.

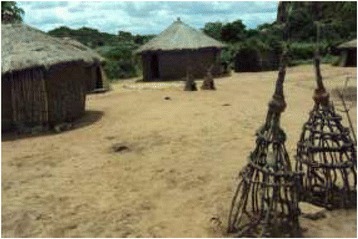

Figure 3.

Ancestral shrines in a rural Sukuma healer’s compound.

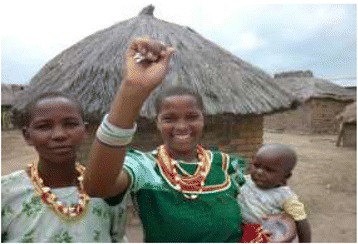

Figure 4.

Sukuma lady with her children and traditional house.

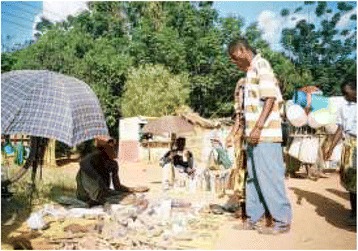

Figure 5.

Traditional healers selling medicines in local market.

Procedures

In order to obtain ethnozoological information about animal and their products used in traditional medicine, a study was conducted from August 2012 to July 2013 in the Busega district of Simiyu region, Tanzania. The ethnomedicinal data (local name of animals, mode of preparation and administration) were collected through semi-structured questionnaire (in their local language mainly Kiswahili, with the help of local mediator), interview and group discussion with selected people of the tribe. The selection of informants was based on their experience, recognition as expert and knowledge old aged person concerning traditional medicine. A total of 180 (118 male and 62 female) people were selected to collect ethnozoological information, these information were collected from local traditional healers, farmers, fisherman and cultural officer. We interviewed 98 (55%) informants within age group 55 and above, followed by 42 informants (23%) with 45 to 54 age group and 40 (22%) with 35–44 years age group.

They were inquired, about the illnesses cured by animal based medicines and the manner in which the medicines were prepared and administered. They were also requested thorough information about mode of preparation and blending of animal products used as ingredients and whether they use animal in the healing practice, since this type of information indicate how a given medicine can be therapeutically effective in term of the right ingredients, the proper dose and the right length of medication. The name of animals and other related information to this study were documented. Some pictures of Sukuma people at their local place and in their life style in study area were taken.

As stated by them, their traditional ethnozoological acquaintance was mainly attained through parental heritage and experience about medicinal value of animal to heal their families or themselves. The scientific name and species of animals were identified using relevant and standard literature [29,30].

Data analysis

For the data analysis, fidelity level (FL) calculated that demonstrates the percentage of respondents claiming the use of a certain animal species for the same illnesses, was calculated for the most frequently reported diseases or ailments as:

Where Np is the number of respondents that claim a use of a species to treat a specific disease, and N is the number of respondents that use the animals as a medicine to treat any given disease [31]. The range of fidelity level (FL) is from 1% to 100%. High use value (close to 100%) show that this particular animal species are used by large number of people while a low value show that the respondents disagree on that spices to be used in the treatment of ailments.

Result and discussion

The present study revealed the traditional medicinal knowledge of treating many types of ailments using different animal and their products by the local Sukuma people inhabitants of Simuyu region, Tanzania. Many old generation people were found to lack formal education, but they have acquaintance about use of local faunal and floral resources for traditional medicinal and other purposes [12], Sukuma people are one of them [Table 1].

Table 1.

Knowledge of animal resource use among Sukuma Tribe of Busega District

| Scientific name | Common name (E) | Local name (S) | Vernacu lar name | Parts used | Traditional Uses | Mode of Preparation | Dosage | Resp onde nt | Use value | Conserv ation status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammals | ||||||||||

| Eudorcas thomsonii (Gunther, 1884) | Thomson’s Gazelle | Nyamela | mbushi | Heart Skin Tail | Treat: asthma, Pneumonia Make drums | Dry, grind pour hot water | Inhale the smoke 1/day*4 days | 145 | 0.80 | Status: NT Trend: D |

| Chase away insect | Mount flesh skin container | |||||||||

| Tail is being dried and used | ||||||||||

| Hippopotamu s amphibious (Linnaeus, 1778) | Hippopotamus | Kiboko | ngubho | Blood | Boost CD4 for HIV patient | Blood dried for 3 days | 3 spoons/day* | 88 | 0.48 | Status: VU |

| 30 days | Trend: D | |||||||||

| Equus quagga (Boddaert, 1785) | Plains Zebra | Pundamilia | ndolo | Hooves | Treat: glands | Burn, grind, mix with water | 2 cup/day*7 days | 122 | 0.68 | Status: LC |

| Trend: S | ||||||||||

| Atherurus africanus (Gray, 1842) | Porcupine | Nungunungu | Nungu | Spines | Treat: abscess | Rub ashes in abscess | 2/day *2 days | 129 | 0.72 | Status: LC Trend: U |

| Crocuta crocuta (Erxleben, 1777) | Spotted Hyena | Fisi | Mbiti | Meat Skin and Feaces | Treat :TB | Eat dry meat Cham | 3 pieces/day*3 days. | 142 | 0.79 | Status: LC |

| For protection | Tie on waist | Trend: D | ||||||||

| Ovis aries (Linnaeus, 1778) | red Maasai sheep | Kondoo | Ng’oro | Fat | Treat: burn | Extract tail fat | Rub everyday | 105 | 0.58 | Status: NA |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Diceros bicornis (Linnaeus, 1778) | Black Rhinoceros | Faru | Mhela | Horn | Treat: asthma, gastritis; TB | Paste the horn mix with hot | 2/ day* 30 days | 96 | 0.53 | Status: CR |

| Trend: I | ||||||||||

| Phataginus tricuspis (Rafinesque, 1821) | African Pangolin | Kakakuona | Murhuka ge | Scales | Goodluck | Make charms. | Tie on hand | 154 | 0.85 | Status: NT |

| Trend: D | ||||||||||

| Atelerix albiventris (Wagner, 1841) | Four-toed Hedgehog | Kalunguyeye | Kilungu miyo | Skin; spines | Stop blood discharge via nostril | Burn; inhale its smoke | Time of suffering | 103 | 0.57 | Status: LC |

| Trend: S | ||||||||||

| Loxodonta Africana (Blumenbach, 1797) | African Elephant | Tembo | Mhole | Skin | Treat: hepatitis | Burn; get ashes | 3 spoon/day*7 days | 2 | .17 | Status: VU |

| Trend: I | ||||||||||

| Mungos mungo (Gmelin, 1788) | Banded Mongoose | Nguchiro | Ng’ara | Nail | Treat: cough | Grind and smell | 2/day | 5 | .13 | Status: LC |

| Trend: S | ||||||||||

| Procavia capensis (Pallas, 1766) | Rock Hyrax | Pimbi | Membe | Urine | Treat: Syphilis | Collect hyrax urinated soil; mix water; filter soil and then drink | 1 cup/day*7 days | 4 | .3 | Status: LC |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769) | Brown Rat | Panya | Kitakilan zela | Whole animal | Protection of thieves | Dry the dead rat. and. | embed on farms center | 48 | .82 | Status: LC |

| Trend: S | ||||||||||

| Kerivoula Africana (Gray, 1842) | Tanzanian Woolly Bat | Popo | Tunge | Whole animal | Treat : pneumonia | Burn and inhale the smoke | 1/day*3 days | 7 | .37 | Status: EN |

| Trend: D | ||||||||||

| Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1778) | Lion | Simba | Shamba | Adipose tissue Skin | Treat ear pus For protection | Rub fat on the ears Make charm | 1/day *4 days Tie on neck | 11 | .62 | Status: VU |

| Trend: D | ||||||||||

| Phacochoeru s africanus (Gmelin, 1788) | Warthog | Ngiri | Ngere | Tusks | Treat stomach ulcers | Grind, mix with hot water | 2 cup/day *7 days | 2 | .28 | Status: LC |

| Trend: S | ||||||||||

| Lepus capensis (Linnaeus, 1778) | Cape Hare | Sungura | Sayayi | Fur | For wound healing | Take the fur burn it and | Rub ashes in the wound. | 8 | .48 | Status: LC. |

| Trend: D | ||||||||||

| Insect | ||||||||||

| Aglais urticae (Linnaeus, 1778) | Butterfly | Kipepeo | Parapapu | Wings | Treat: chest pain. | Grind; Swallow powder | 3/day*5 days. | 5 | .25 | Status: NA |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Lasius niger (Linnaeus, 1778) | Black ants | Chungu | Sungwa | Whole organism. | To become intelligent and leader | Take the fore ant, grind and rub on head | 1/day*3 days | 29 | .72 | Status: |

| LC Trend: S | ||||||||||

| Butastur rufipennis (Sundevall, 1851) | Grasshopper Buzzard | Panzi | Ng’umbe | Whole organism | Treat: stomachache; heartbeat | Burn, grind it into powdery form. | Rub 2/day*3 days | 54 | .86 | S tatus: LC |

| Trend: D | ||||||||||

| Apis mellifera (Linnaeus, 1778) | Honey bee | Nyuki | Nzoke | Honey | Treat: burn | Rub the burn | 2/day*3 days | 38 | .76 | Status: NA |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Beetle | Kalilila | Kombam wiko | Whole organism | Call a person to come back home | Burn beetle and call the name of a person. | 3/day*3 days | 48 | .82 | Status: NA | |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Chilopoda | ||||||||||

| Scutigera coleoptrata (Linnaeus, 1778) | Millipede | Tandu | Whole | Treat Dandruff | Burn and swallow the ashes. | 1/day*3 days | 45 | .25 | Status: NA | |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Arachnida | ||||||||||

| Araneus spp (Clerck, 1757) | Spider | Buibui | Spider web | Stop bleeding. | Apply direct on fresh wound. | Once/ day | 99 | .55 | Status: LC | |

| Trend: S | ||||||||||

| Diplopoda | ||||||||||

| Trigoniulus corallines (Gervais, 1847) | Millipede | Jongoo | Igongoli | Whole body | Treat dandruff | Press plasma fluid and swallow | 2/day*2 days | 2 | .51 | Status: NA |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Reptiles | ||||||||||

| Naja siamensis (Laurenti, 1768) | Cobra | Cobra | Kipele | Skin | Treat: burns fractured bone | Powder the skin, mixed with water | Rub 2/day*3 days | 129 | .72 | Status: VU |

| Trend: D | ||||||||||

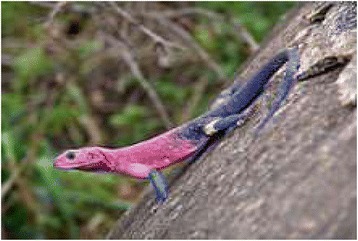

| Agama mwanzae (Loveridge, 1923) | Flat-headed Rock Agama | Mjusi | Madhore | Bile | Treat dysentery. | Drink flesh bile | 1 spoon/day*3 days | 8 | .43 | Status: LC |

| Trend:S | ||||||||||

| Python regius (Shaw, 1802) | Royal Python | Chatu | Nsato | Feaces | Treat back pain | Mix with little water | Rub on back 2/day*3 | 23 | .68 | Status: LC |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Crocodylus niloticus (Laurenti, 1768) | Nile Crocodile | Mamba | Ng’wina | Skin | Treat TB: gastritis. | Burn and swallow the ashes | 2/day*7 days | 78 | 0.43 | Status: LC |

| Trend: S | ||||||||||

| Aves | ||||||||||

| Baleara reguloum (Bennett, 1834) | Grey Crowned crane | Korongo | Izunya | blood | Treat stomach ulcers | Drink flesh blood | 3/day*2 days | 117 | 0.65 | Status: EN |

| Trend: D | ||||||||||

| Aquila rapax (Temminck, 1828) | Tawny Eagle | Tai | Mbeshi | Feathers | Treat chest pain. | Burn and inhale the smoke | 15 minutes/day*3 days | 108 | 0.60 | Status: LC |

| Trend: S | ||||||||||

| Gallus domesticus (Linnaeus, 1778) | chicken | Kuku | Ng’oko | Fat Egg white | Nasal congestion. Treat: dysentery | Rub the fat in the nasal Drink egg white | 3/day*3 days Twice a day | 145 | 0.81 | Status: NA |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Threskiornis aethiopicus (Latham, 1790) | African Sacred Ibis | Nyangenyang e | Nzela | Blood | Treat: rheumatism | Drink flesh blood | 1/2 cup/day*7 days | 59 | 0.32 | Status: LC |

| Trend: D | ||||||||||

| Ceryle rudis (Linnaeus, 1778) | Pied Kingfisher | Ndobhelendo bhele | Fat | Treat: back pain | Massaged on the back | 2/day*4 days | 142 | 0.79 | Status: NT | |

| Trend: D | ||||||||||

| Dendropicos stierlingi (Reichenow, 1901) | Stierling's Woodpecker | Fulubeji | Intestinal fecal content | Treat: diarrhea | mix hot water with fecal content | 2 cup/day*3 days | 45 | 0.25 | Status: NT | |

| Trend: S | ||||||||||

| Anas indica (Linnaeus, 1778) | Duck | Bata | Mbata | Fat | Treat: Pneumonia, Chest pain | Wormed and massaged on the chest | 3/day*3 days | 92 | 0.51 | Status: NA |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Fish | ||||||||||

| Mormyrus kannume (Forsskal, 1758) | Elephant snout fish | Domodomo | Shironge | Whole organism | Treat: hookworms; removal poisonous | Burn, grind, mix with hot water | 1 cup/day*3 days. | 169 | 0.94 | Status: LC |

| Trend: D | ||||||||||

| Lates niloticus (Linnaeus, 1778) | Nile Perch | Sangara | Mbuta | Gills | Treat: abdominal cramp | Pound and mix with water | 1 cup/day*7 days | 85 | 0.47 | Status: LC Trend: U |

| Oreochromis variabilis (Boulenger, 1906) | Victoria tilapia | Sato | Sato | Scales | Treat: cough | Burn and swallow the ashes | Regularly. | 145 | 0.81 | Status: CR |

| Trend: D | ||||||||||

| Octopus vulgaris (Cuvier, 1797) | Common octopus | Pweza | Naghala | Tail | Treat: Urinary retention | Burn and swallow its ashes | 2/day*3 days | 25 | 0.13 | Status: NA |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Gastropod | ||||||||||

| Snail (O.F. Muller, 1774) | Achatina fulica | Konokono | Nonga | Shell | Treat: leg pain; make chain | Burn, grind, mix with water | Rub 2/day .*3 days | 132 | 0.73 | Status: NA, |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

| Oligochaeta | ||||||||||

| Lumbricus terrestris (Linnaeus, 1778) | Earthworm | Mnyoo | Whole | Treat impotence | Dry; paste mix with hot water | 2 spoon/day *7 days | 99 | 0.55 | Status: NA | |

| Trend: U | ||||||||||

LC = Least Concern, NT = Near Threatened, VU = Vulnerable, EN = Endangered, CR = critically endangered, NA = Not Assessed, I = Increasing, D = Decreasing, S = Stable, U = Unknown, * = Times, E = English, S = Swahili.

The Table 1 shows that, Sukuma people of Busega district were using 42 animal species for the treatment of over 30 different kinds of illnesses. The animal species used as traditional medicine by these people comprise of seventeen mammals, seven birds, four reptiles, eight arthropods and two mollusks species. Highest number of animal belonged to mammalian taxonomic group (n = 17, 41%), birds (n = 7, 17%), reptiles (n = 4, 9.5%), fishes (n = 4, 9.5%) and arthropods (n = 8, 19%) respectively. Sukuma people use these animal and their products for the treatment of more than 30 types of different illnesses including asthma, paralysis, cough, fever, cold, STD, wound healing etc. These animals were used as whole or byproducts of these animals like milk, blood, organ, flesh, tooth, urine, honey, feather etc. for the treatment of various illnesses and used in the preparations of traditional medicine [Figures 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13].

Figure 6.

Threskiornis aethiopicus.

Figure 7.

Butastur rufipennis.

Figure 8.

Agama Mwanzae.

Figure 9.

Trigoniulus corallines.

Figure 10.

Skin of Panthera leo.

Figure 11.

Dried Mormyrus kannume.

Figure 12.

Achatina Fulica Shell.

Figure 13.

Dried Asterias sp.

Fidelity levels (FL) demonstrate the percentage of respondents claiming the use of a certain animals for curing of the illness. The uses of animals that are generally known by the Sukuma respondents have higher fidelity level is shown in Table 1.

Table: 1 also shows that cough, Tuberculosis, asthma, and other respiratory diseases are most frequently quoted disease among Sukuma people, as such, a number of traditional medicine are available for the treatment of such diseases, many animal byproducts were used like flesh of gazelle, horn of rhino, nail of mungos, and honey are some of them. Another important aspect of the present study that needs to be mentioned is that the Sukuma people also use some endangered, vulnerable and near threatened animal species as medicinal resources. A total of 42 identified animal species, of which 12 (28.57%) are included in the IUCN Red Data list [32]. It is important to mention here that species such as Tanzanian woolly bat, grey crowned crane, are listed as endangered while Black rhino and Victoria tilapia are listed as critically endangered and hippopotamus, African elephant, Simba (Panthera leo), Cobra (Naja siamensis) are listed as vulnerable in IUCN Red Data list. These tribal people have scarce knowledge, many irrational belief and myths associated with customs that cause harm to animal life. Thus these traditional medicine and animals byproducts should be tested for their appropriate medicinal components, if cited animal species among these people, byproducts of these animals, were used in the treatment of various illnesses.

Sukuma people also use one animal product with other animal products or plant derivatives to found indefensible, the people should be aware about the endangered and protected animal species and their importance in biodiversity. Consequently, the socio-ecological system has to be strengthened through sustainable management and conservation of biodiversity [33] [Table 2].

Table 2.

Conservation status of animal utilized in traditional medicine

| IUCN red list category 2013 | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Least concern | 20 | 47.62 |

| Near threatened | 04 | 9.52 |

| Vulnerable | 04 | 9.52 |

| Endangered | 02 | 4.76 |

| Critically endangered | 02 | 4.76 |

Main threats of conservations in Tanzania includes overexploitation of natural resources due to poverty, rapid human population growths, weak wildlife policy and legislations, habitat alterations as well as inadequate funding. Poaching or illegal off take of wildlife resources has gone continuously regardless of wildlife conservation laws. However, traditional hunters in Tanzania have not been serious threat to wildlife. Wildlife populations are threatened by commercial poaching in which animal are used in bush meat trade and traditional medicine [34]. Despite medicinal purpose, Sukuma people also use animal resources for other purpose in their daily life. The Sukuma people use slough (molted skin of various animals) to decorate their traditional houses and this type of decoration are also reported in many other tribes living in other parts of Tanzania [Figures 14, 15, 16, 17].

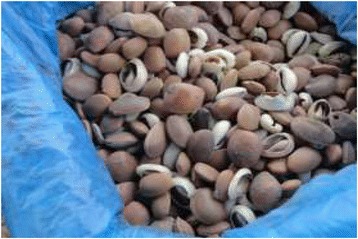

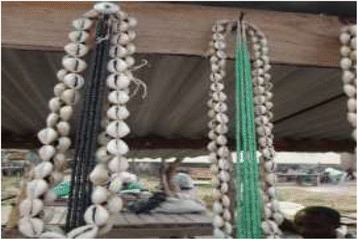

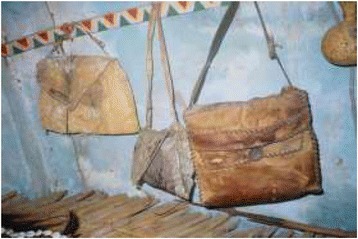

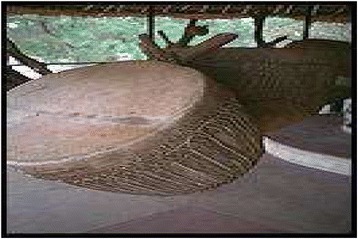

Figure 14.

Different products obtained from animal resources among Sukuma Tribes.

Figure 15.

Different products obtained from animal resources among Sukuma Tribes.

Figure 16.

Different products obtained from animal resources among Sukuma Tribes.

Figure 17.

Different products obtained from animal resources among Sukuma Tribes.

Conclusion

The current study shows that forty two animals were found to be used among Sukuma tribe of Busega district. Twelve animal species are officially considered as threatened species by IUCN red list (2012) were found among the set of faunistic resources prescribed as medicines at the time of this research. The latter author noted that Sukuma healers who are also diviners are more likely to use both wild and domesticated animals in their diagnoses. Moreover mammals, reptiles, birds, fish, and amphibians have been used in the field of traditional medicine for different purposes. However, mammals seem to be used much (40.50%) compare to other group among Sukuma tribe, followed by aves (16.7%). Amphibians are not commonly used in Sukuma society.

The present study also shows that the Sukuma people have very rich folklore and traditional knowledge in the utilization of different animal. So there is an urgent need to properly document to keep a record of the ethnomedicinal data of animal products and their medicinal uses. More studies are prerequisite for scientific validation to endorse medicinal value of such products and to include this knowledge in policies of conservation and management of animal resources. We hope that the present information will be helpful in further research in the field of ethnozoology, ethnopharmacology and biodiversity conservation viewpoint.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to the Head and Dean of Biological sciences for providing all facilities and reinforcements during the study. We are also highly grateful to all the respondents who shared their traditional ethnozoological knowledge and permitted us to take pictures. Without their involvement, this study would have been impossible.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors had significant intellectual contribution towards the design of the field study, data collection, data analysis and write-up of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Rajeev Vats, Email: Vatsr71@gmail.com.

Simion Thomas, Email: thomassimion17@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Alves RRN. Relationships between fauna and people and the role of ethnozoology in animal conservation. Ethnobiol Conserv. 2012;1(2):1–69. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Judith H: Information Resources on Human-Animal Relationships Past and Present. AWIC (Animal Welfare Information Center). Resource Series No. 30 2005

- 3.Lohani U, Rajbhandari K, Shakuntala K. Need for systematic ethnozoological studies in the conservation of ancient knowledge system of Nepal - a review. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2008;7(4):634–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lev E. Traditional healing with animals (zootherapy): medieval to present-day Levantine practice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;85:107–18. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00377-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO/IUCN/WWF: Guidelines on Conservation of Medicinal Plants. Switzerland 1993.

- 6.Marques JGW. Fauna medicinal: recurso do ambiente ou ameaça à biodiversidade? Mutum. 1997;1(1):4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alves RRN, Rosa IL, Santana GG. The q in Brazil. Bio Sci. 2007;57(11):949–55. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa-Neto EM. Implications and applications of folk zootherapy in the state of Bahia. Northeastern Brazil Sustain Dev. 2004;12(3):161–74. doi: 10.1002/sd.234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.China National Corporation of Traditional and Herbal Medicine . Materia medica commonly used in China Beijing. China Beijing: Science Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alves RRN, Rosa IL. Zootherapy goes to town: The use of animal-based remedies in urban areas of NE and N Brazil. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113:541–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lev E, Amar Z. Ethnophrmacological survey of traditional drugs sold in Israel at the end of the 20th century. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;72:191–205. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamang G. An ethnozoological study of the Tamang people. Our Nat. 2003;1:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alves RRN, Rosa IL. Zootherapeutic practices among fishing communities in North and Northeast Brazil: a comparison. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;111:82–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alves RRN, Vieira WL, Santana GG. Reptiles used in traditional folk medicine: conservation implications. Biodivers Conserv. 2008;17(1):2037–49. doi: 10.1007/s10531-007-9305-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alves RRN. Fauna used in popular medicine in Northeast Brazil. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2009;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lev E, Amar Z. Ethnophrmacological survey of traditional drugs sold in the kingdom of Jordan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;82:131–45. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tripathy BB. Drabya Guna Kalpa Druma, Orissa (Vols. I & II). Publ. D.P. Tripathy, Bellaguntha (Ganjam District), 5 1995

- 18.DP Jaroli DP, Mahawar MM, Vyas N. An ethnozoological study in the adjoining areas of Mount Abu wildlife sanctuary. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6(6):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simoons FJ. The purification rule of the five products of the cow in Hinduism. Ecol Food Nutr. 1974;3:21–34. doi: 10.1080/03670244.1974.9990358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mbwambo ZH, Mahunnah RA, Kayombo EJ. Traditional health practitioner and the scientist: bridging the gap in contemporary health research in Tanzania. Tanzania Health Res Bull. 2007;9(2):115–120. doi: 10.4314/thrb.v9i2.14313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002-05, WHO/EDM/TRM2002.1, 2002, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland

- 22.Oudhia P. Traditional knowledge about medicinal insects, mites and spiders in Chhattisgarh. India: Insect Environment; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kisangau DP, Lyaruu HVM, Hosea KM, Joseph CC. Use of traditional medicines in the management of HIV/AIDS opportunistic infections in Tanzania: a case in the Bukoba rural district. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clack TAR. Culture, History and Identity: Landscapes of Inhabitation in the Mount Kilimanjaro Area, Tanzania. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.United Republic of Tanzania (URT) Traditional and Alternative Medicine Act No. 23 of 2002, United Republic of Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: Government Printer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Rwetabula JF, Smedt RM, Mwanuzi F. Submitted and presented at The 1st International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA January 23-26th. 2004. Transport of micro pollutants and phosphates in the Simiyu River (tributary of Lake Victoria), Tanzania; p. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cory H. Sukuma law and custom. London: Oxford University Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birley MH. Resource Management in Sukumaland, Tanzania, Africa. J Int Afr Inst. 1982;52:1–30. doi: 10.2307/1159139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali S. The book of Indian Birds. Bombay: Bombay: Natural History Society; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prater SH. The Book of Indian Animals. Bombay: Bombay Natural History Society; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexiades MN. Selected Guidelines for Ethnobotanical Research: A Field Manual. 1996. p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 32.The IUCN Red List of Threatened species. 2009, http://www.iucnredlist.org

- 33.Kakati LN, Bendang A, Doulo V. Indigenous knowledge of zootherapeutic use of vertebrate origin by the Ao Tribe of Nagaland. J Hum Ecol. 2006;19(3):163–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Severre EM. Conservation of wildlife outside core wildlife protected areas in the new millennium, millennium conference. Mweka, Tanzania: College of African Wildlife Management; 2000. [Google Scholar]