Abstract

Aim

Gallbladder cancer is an aggressive malignancy usually diagnosed at late stage. The molecular genetics of this cancer is heterogeneous and not well established. Mutation profiling of gallbladder cancer was performed through massarray technology with an aim to identify molecular markers involved in the tumor pathogenesis that can be helpful as markers for early diagnosis and targets for therapy.

Materials and Methods

Forty nine cases of gallbladder cancer were screened through Sequenom Massarray technology for 390 mutations across 30 genes in formalin fixed paraffin embedded archived tissues and the results of mutation profiling was correlated with tumor characteristics. Mutations were observed in 9 of 49 cases across four genes - TP53 (four cases), CTNNB1 (two cases), PIK3CA (two cases), and KRAS (one case). Six of these cases were well differentiated but of eight of them belonged to stage II to IV disease. Six cases had associated gallstones.

Conclusion

The mutation frequency found in gallbladder cancer is comparable to the data available in literature. Identification of PIK3CA and KRAS mutations would help in formulating more efficacious targeted approach for management. Studies with large number of cases would help in exploring more targets and better classification of these cancers at genetic level.

Introduction

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is one of the most aggressive malignancies with an extremely poor prognosis. Surgical resection remains the only chance of cure but is possible in only a small percentage of patients with GBC. The 5-year survival rate for cancers confined to gallbladder is 32% and for advanced stage cancers is 10%. [1],[2] The limited efficacy of cytotoxic therapy for advanced biliary tract and gallbladder cancers emphasizes the urgent need for novel and more effective medical treatment options.

A combination of predisposing factors makes GBC a unique tumor and offers potential for understanding cancer pathogenesis. These factors include ethnicity, genetic predisposition, geographic location, female gender, chronic inflammation, and congenital developmental abnormalities. Epidemiologic studies have indicated a very strong association of this cancer with gender, ethnicity, and geographic distribution.

To date there has been little translational research in this disease, and GBC is still an ‘orphan’ cancer throughout the world. Several factors have contributed to our poor understanding of GBC include rarity in the western world, availability of very few cell lines, no reliable animal models, very few well-maintained registries and lower rates of resectability (which translates into reduced availability of tumor tissue for characterization).

Accurate diagnosis is important for both determining prognosis and effective treatment modality. Newer therapeutic agents are being developed for treating cancer which is changing the cancer management practice. Cancer-specific signaling pathways are being extensively explored and this has introduced the concept of targeted therapy representing an important approach in clinical cancer therapy. Somatic mutations occurring in intracellular signaling pathways cause aberrant activation of the signaling molecules. These mutations have transformed the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Different subtypes of cancer harbor specific gene mutations that act as invaluable markers for disease diagnosis and prognosis. Many of the mutated proteins also represent targets for novel therapeutic agents that are more specific, more efficacious, and less toxic than broad-based chemotherapeutic regimens. Identification of the relevant molecular subtypes requires high-throughput technologies of which mass spectrometry-based panel of multiplexed assays (Sequenom MassARRAY) is one of them. The Sequenom Massarray system is a sensitive and rapid medium throughput platform for mutation profiling in solid tumors, capable of screening hundreds of mutations simultaneously through the use of mass spectroscopy. [3]

The poor prognosis and high incidence of GBC in North India necessitates a closer look at the molecular changes for evolving an effective early diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic strategy. There is a very scarce literature in India regarding the expression of different genes in GBC. Uncovering patterns of genetic change within GBC is critical to improving therapy as well as gaining insight into disease biology. A better understanding of molecular and genetic profiling of GBC is likely to be of predictive and prognostic value.

Materials and Methods

Forty nine retrospective cases of GBC were identified for the study. The hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides were reviewed for tumor type, histological grade, depth of infiltration, lymph node, and distant metastasis and associated xanthogranulomatous inflammation. Paraffin blocks of representative sections with more than 70% tumor content were selected for DNA extraction using a Qiagen kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was amplified and screened for mutations across a panel of 30 genes [Table 1].

Table 1.

Genes screened for mutations by mass array

| Genes | Genes |

|---|---|

| ABL | GNAQ |

| AKT1 | HRAS |

| AKT2 | KIT |

| AKT3 | JAK2 |

| BRAF | KRAS |

| CDK | MAP2K1 |

| CTNNB1 (b-catenin) | MAP2K2 |

| EGFR | MET |

| ERBB2 (HER2) | NRAS |

| FBX4 | PDGFRA |

| FBXW7 | PIK3CA |

| FGFR1 | PTPN11 |

| FGFR2 | RET |

| FGFR3 | SOS1 |

| FLT3 | TP53 |

Mutation screening

Mutation screening was performed using a panel of 324 assays in which 390 mutations in 30 genes were analyzed on a MassARRAY platform (Sequenom, San Diego, CA). This solid tumor panel includes all of the assays that are part of the commercially available OncoCarta v01 panel (Sequenom), as well as 136 custom-designed assays that are now also commercially available (OncoCarta v02, Sequenom). Assay Designer 3.1 software (Sequenom) was used to design assay multiplexes targeting mutations in known cancer genes, and assays were performed using Type- PLEX (Sequenom) chemistry. Initial PCR reactions were set up with an EpMotion 5075 liquid handler (Eppendorf), and used 10 ng DNA per multiplex in a total volume of 5 μl, with 100 nmol/L primers, 2 mmol/L MgCl2, 500 mmol/L dNTPs, and 0.1 units Taq polymerase. Amplification included one cycle of 94°C for 4 min, followed by 45 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and one final cycle of 72°C for 3 min. Unincorporated nucleotides were inactivated by addition of 0.3 U shrimp alkaline phosphatase and incubation at 37°C for 40 min, followed by heat inactivation of shrimp alkaline phosphatase at 85°C for 5 min. Single base primer extension reactions were performed with 0.625 to 1.25 mol/L extension primer and 1.35 units TypePLEX thermo sequenase DNA polymerase. Extension cycling included one cycle of 94°C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 94°C for 5 s, five cycles of 52°C for 5 s and 80°C for 5 s, followed by one cycle of 72°C for 3 min. Extension products were purified by incubation for 30 min with an ion exchange resin (SpectroCLEAN, Sequenom), and approximately 10 nl of purified product was spotted onto SpectroChip II matrices. A Bruker matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometer (MassARRAY Compact, Sequenom) was used to resolve extension products. MassARRAY Typer Analyzer software (Sequenom) was used for automated data analysis, accompanied by visual inspection of extension products.

For each sample analyzed, the mass spectrometry profiles for all 36 multiplexes were manually reviewed and the results were read as wild-type, ‘low confidence’ for mutation (peak area between 10% and 20% of wild-type), or ‘high confidence’ for mutation (peak area 20% of wild-type). In cases with a low confidence result, Sanger sequencing was performed and the mutation was only called when confirmed by this secondary test.

DNA sequencing

Sanger sequencing was performed using an ABI 3130 sequencer.

Results

The age range was between 32 to 90 years with a mean of 58.1 years. Male to female ratio was 1:2.8 (37 females and 13 males). Histological examination showed 46 cases of adenocarcinoma, two cases of adenosquamous carcinoma and one case of squamous cell carcinoma. Thirty four of these were well differentiated, eight cases were moderately differentiated, seven cases were poorly differentiated and one case was undifferentiated. Lymph node metastasis was seen in 20 cases and peritoneal metastasis was seen in one case in the peritoneum which was a poorly differentiated carcinoma. Gallstones were present in 29 (58%) cases and xanthogranulomatous inflammation was seen in eight cases (16%).

Nine cases of GBC showed mutation in four of thirty genes (CTNNB1, KRAS, p53, and PIK3CA). Four cases showed mutation for p53, two cases each for CTNNB1 and PIK3CA and one case showed mutation in KRAS [Table 2], [Figure 1]. No mutation was detected in 40 cases of GBC. Five of nine cases which showed mutation were females and four were males. Five of nine cases with mutation were of grade I, one of grade II and rest three were grade III tumors with stage ranging between stages II to IV. Three cases had associated cholelithiasis and none had xanthogranulomatous inflammation. The follow-up was available in six cases with maximum survival of 43 months and three cases were lost to follow-up. Relations of mutations in GBC with tumor characteristics are given in [Table 3]. {Figure 1}{Table 1}{Table 2}{Table 3}

Table 2.

Mutations detected in gallbladder cancer

| Gene mutated | Exon | Genotype | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTNNB1 | 3 | T41A | Mass Array |

| CTNNB1 | 3 | S45F | Mass Array |

| KRAS | 1 | G12S | Mass Array |

| PIK3CA | 9 | H1047R | Mass Array |

| PIK3CA | 9 | E545K | Mass Array |

| TP53 | 5 | R175H | Mass Array |

| TP53 | 8 | R273C | Sequence |

| TP53 | 8 | D281G | Mass Array |

| TP53 | 8 | R273C | Mass Array |

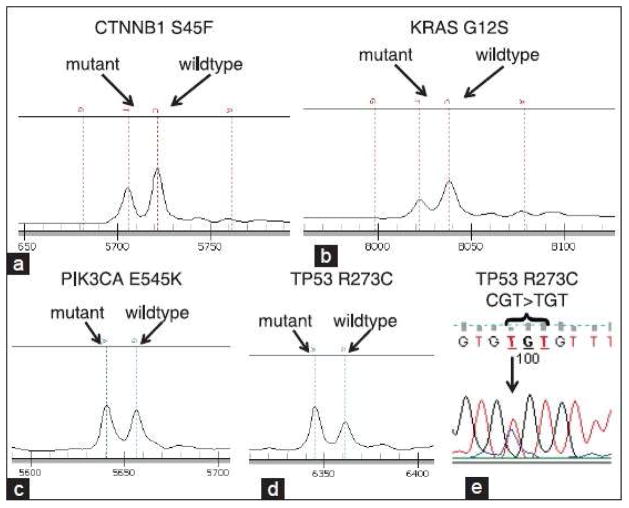

Figure 1.

Mutation detection by MassARRAY and Sanger sequencing. Primer extension products were detected by mass spectrometry, including (a) CTNNB1 S45F, (b) KRAS G12S, (c) PIK3CA E545K, and (d) TP53 R273C. The positions of primer extension products with wildtype and mutant alleles are indicated. (e) Sanger sequence detection of the TP53 R273 mutation depicted in (d)

Table 3.

Correlation of genotype with tumor characteristics

| S No. | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | Case 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | CTNNB1 | CTNNB1 | KRAS | PIK3CA | PIK3CA | TP53 | TP53 | TP53 | TP53 |

| Exon | 3 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Genotype | T41A | S45F | G12S | H1047R | E545K | R175H | R273C | D281G | R273C |

| Age/Sex | 35/M | 43/F | 68/M | 65/F | 61/M | 58/F | 53/F | 76/M | 44/F |

| Tumor type | AC | AC | AC | AC | AC | AC | Papillary AC | Papillary AC | AC |

| Tumor grade | G1 | G2 | G3 | G1 | G1 | G3 | G1 | G1 | G3 |

| T-stage | T2 | T2 | T2 | T3 | T3 | T3 | T2 | T2 | T3 |

| LN metastasis | Present | Present | Absent | Absent | Present | Present | Absent | Present | Present |

| PNI | Absent | Absent | Absent | Present | Absent | Present | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| LVI | Present | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Distant metastasis | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Gallstones | Absent | Absent | Absent | Present | Absent | Absent | Absent | Present | Present |

| Overall stage | IIIB | IIIB | II | IIIA | IIIB | IVB | II | IIIB | IIIB |

| Survival | 30 M | 43 M | 5 M | 5 M | 23 M | 17 M | 11 M | 32 M | 4 M |

AC: Adenocarcinoma; G-grade; LN: Lymph node; PNI: Perineural invasion; LVI: Lymphovascular invasion

Discussion

Cancer genetics of solid malignancies is a continuously expanding and evolving field and is being applied in decision making for management of various solid tumors. A number of established oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes which include KRAS, PIK3CA, MAPK, CTNNB1, TP53, KIT, and PDGFRA have been studied in various cancers like colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer and gastrointestinal stromal tumors, etc. The frequency of mutation of these common genes in GBC is not well established, but is important for increasing our understanding of the disease biology, and possibly for predicting drug sensitivity or resistance.

In the panel of 30 genes examined in this study mutations were only detected in four genes (18%) amongst the GBC studied [Table 2]. Deshpande et al. studied mutation profiling of biliary tract cancers across 24 genes and found two genes (NRAS and PIK3CA) to be mutated in their 18.8% of GBC. [4]

TP53 was mutated in 8% (four cases) of GBC in this study and seen in well to poorly differentiated and papillary adenocarcinoma. This is in contrast to the study by Kim et al. who found 35.7% of their GBC to have TP53 mutation; however, they used different technique (single stranded conformational polymorphism). [5] Rashid et al. found TP53 mutation in 27.6% cases of GBC and all the cases were histologically either adenocarcinoma or papillary adenocarcinoma which was similar to the results of this study. [6]

Mutations in PIK3CA were found in two cases (4%) in GBC in this study of whom both were well differentiated. The PIK3CA mutations were seen in exon 9 in both cases. The PIK3CA mutations occur commonly in exon 9 and 20 which are the commonest hot spots. Deshpande et al. showed PIK3CA mutation in 4 (12.5%) of 32 cases of GBC in their study. [4] Riener et al. had similar results as ours and found 4% of PIK3CA mutation in GBC in their study. [7] High rates of PIK3CA mutations have been found in colorectal, hepatocellular, endometrial, and breast cancers. [4]

Mutations in CTNNB1 were found in another two cases (4%) in GBC in this study with one in well differentiated and other in moderately carcinoma. Rashid et al. found CTNNB1 mutation in 9% of GBC in their study. [8] Yanagisawa et al. found CTNNB1 mutation in 4.8% of GBC in contrast to 62.5% of gallbladder adenoma and suggested the adenoma-carcinoma sequence to be a minor pathway in gallbladder carcinogenesis as opposed to colorectal carcinogenesis. [9]

KRAS mutations in biliary tract cancer have been found commonly in the setting of anomalous junction of pancreatic and biliary ducts. KRAS mutation in exon 1 was found in one case in the present study. There is wide variation in KRAS mutation in GBC ranging from 3% to 36% in different studies. [5],[6],[10],[11] Deshpande et al. did not find any KRAS mutation in their study; however, they found NRAS mutation in their two cases (6.3%) of GBC. [4]

The MassARRAY approach of mutation profiling has yielded some preliminary data in the molecular characterization of GBC genetics. The mutations detected in GBC in this study have been found in the well-known oncogenes that are seen in a number of gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal cancers and their frequency is comparable with the data in literature for some of the genes. Mutations in PIK3CA and KRAS are clinically relevant because of the ongoing clinical development of PI3 kinase and MEK inhibitors, respectively. The next approach would be to do exome sequencing or whole genome sequencing with the application of next generation sequencing. This would help in providing further insight in the pathogenesis of GBC and to identify various prognostic markers and therapeutic targets in future.

Conclusions

Mutation profiling of solid tumors has become critical in the era of targeted therapy. GBC is one of most aggressive malignancy which has a very poor cure rate even after surgery. In this study we found PIK3CA mutations in 4% and KRAS mutations in 2% of GBC. In addition, CTNNB1 and TP53 mutations were present in 4% and 18% of GBC, respectively. The mutation frequency found in GBC in the present study is comparable to the data available in literature. The identification of PIK3CA and KRAS mutations in GBC would help in formulating a more efficacious targeted approach for management. Studies with large number of cases with application of next generation sequencing would help in exploring more targets and better classification of these cancers at genetic level.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by UICC fellowship to Dr. Niraj Kumari.

References

- 1.Abi-Rached B, Neugut AI. Diagnostic and management issues in gallbladder carcinoma. Oncology (Williston Park) 1995;9:19–24. discussion 24, 27, 30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henson DE, Albores-Saavedra J, Corle D. Carcinoma of the gallbladder. Histologic types, stage of disease, grade, and survival rates. Cancer. 1992;70:1493–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920915)70:6<1493::aid-cncr2820700608>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beadling C, Heinrich MC, Warrick A, Forbes EM, Nelson D, Justusson E, et al. Multiplex mutation screening by mass spectrometry evaluation of 820 cases from a personalized cancer medicine registry. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13:504–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deshpande V, Nduaguba A, Zimmerman SM, Kehoe SM, Macconaill LE, Lauwers GY, et al. Mutational profiling reveals PIK3CA mutations in gallbladder carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YT, Kim J, Jang YH, Lee WJ, Ryu JK, Park YK, et al. Genetic alterations in gallbladder adenoma, dysplasia and carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2001;169:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00562-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rashid A, Ueki T, Gao YT, Houlihan PS, Wallace C, Wang BS, et al. K-ras mutation, p53 overexpression, and microsatellite instability in biliary tract cancers: A population-based study in China. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3156–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riener MO, Bawohl M, Clavien PA, Jochum W. Rare PIK3CA hotspot mutations in carcinomas of the biliary tract. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:363–7. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rashid A, Gao YT, Bhakta S, Shen MC, Wang BS, Deng J, et al. Beta-catenin mutations in biliary tract cancers: A population-based study in China. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3406–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanagisawa N, Mikami T, Saegusa M, Okayasu I. More frequent beta-catenin exon 3 mutations in gallbladder adenomas than in carcinomas indicate different lineages. Cancer Res. 2001;61:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanada K, Tsuchida A, Iwao T, Eguchi N, Sasaki T, Morinaka K, et al. Gene mutations of K-ras in gallbladder mucosae and gallbladder carcinoma with an anomalous junction of the pancreaticobiliary duct. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1638–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe H, Date K, Itoi T, Matsubayashi H, Yokoyama N, Yamano M, et al. Histological and genetic changes in malignant transformation of gallbladder adenoma. Ann Oncol. 1999;10(Suppl 4):136–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]