Abstract

Current perspective holds that the generation of secondary signaling mediators from nitrite (NO2−) requires acidification to nitrous acid (HNO2) or metal catalysis. Herein, the use of stable isotope-labeled NO2− and LC-MS/MS analysis of products revealed that NO2− also participates in fatty acid nitration and thiol S-nitrosation at neutral pH. These reactions occur in the absence of metal centers and are stimulated by nitric oxide (•NO) autoxidation via symmetrical dinitrogen trioxide (nitrous anhydride, symN2O3) formation. While theoretical models have predicted physiological symN2O3 formation, its generation is now demonstrated in aqueous reaction systems, cell models and in viv, with the concerted reactions of •NO and NO2− shown to be critical for symN2O3 formation. These results reveal new mechanisms underlying the NO2− propagation of •NO signaling and the regulation of both biomolecule function and signaling network activity via NO2−-dependent nitrosation and nitration reactions.

The signaling responses and chemical reactions induced by nitric oxide (•NO) during both physiological and metabolically-stressed conditions affirm that, in addition to the activation of guanylate cyclase-dependent cGMP production, non cGMP-dependent reactions contribute to •NO regulation of biomolecule structure and function. In this regard, the S-nitrosation of protein thiols by •NO can modulate protein function and downstream metabolic responses including vascular homeostasis, ion transport, cytoskeletal function and mitochondrial respiration 1. The mechanisms responsible for S-nitrosothiol formation remain controversial and can include membrane-catalyzed •NO autoxidation, •NO reaction with heme centers, formation of dinitrosyl iron complexes, •NO reaction with thiyl radicals and thiols followed by one-electron oxidation, and thiol reaction with dinitrogen trioxide (nitrous anhydride, N2O3) 2-6. The biological relevance of S-nitrosothiol formation in general, and S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) in particular, is supported by studies showing that alterations in the activity of a class III alcohol dehydrogenase, an enzyme that also metabolizes nitrosothiols, modulates the nitrosothiol proteome and physiological responses of murine models 7,8.

Many of the reactions that yield nitrosating intermediates also produce the nitrating species nitrogen dioxide (•NO2). The nitration of protein tyrosine and tryptophan residues by •NO2 may influence signaling networks but, unlike S-nitrosation, protein nitration is an irreversible and typically toxic post-translational protein modification (PTM) that occurs in concert with additional amino acid oxidation reactions 9. In contrast, unsaturated fatty acids and guanine nucleotides are also nitrated by •NO2 to yield electrophilic nitroalkene derivatives that react with nucleophilic cysteine and histidine residues of proteins. In vitro and in vivo studies support that the patterns of PTMs induced by “soft” nitroalkene electrophiles are not toxic and serve to link enzyme and transcriptional regulatory protein function with metabolic and inflammatory status 10-12. For example, conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) is a physiological target of nitration, giving rise to nitro-conjugated linoleic acid (NO2-CLA) regioisomers that are detectable in the urine and plasma of healthy humans at nM concentrations 13,14. The levels of cell and tissue nitroalkenes are modulated by diet and oxidative inflammatory reactions involving •NO or nitrite (NO2−) 13,15,16.

Besides its dietary origin, NO2− is also a product of •NO autoxidation (reactions 1-4). In fact, •NO autoxidation is typically monitored by either measuring NO2− formation or the oxidation of fluorescent and chromogenic probes 4,17,18.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

While these techniques accurately reflect reaction kinetics, none are capable of assessing whether NO2− reacts with nitrogen oxides derived from •NO autoxidation. Herein, isotopic labeling and LC/MS-MS analyses showed that both in chemical reaction systems and activated macrophages, 15N-nitrite (15NO2−) reacts with species generated during •NO autoxidation at physiological pH to yield the unsaturated fatty acid nitration product 15NO2-CLA. Furthermore, we demonstrated that 15NO2− also promotes GSH nitrosation, yielding 15N-labeled GSNO (GS15NO). These observations motivated additional study, as current paradigms hold that either an acidic environment capable of protonation of NO2− to HNO2 (pKa 3.46) or electron transfer reactions between NO2− 2and metal centers are required for the generation of secondary reactive species from NO2−. More specifically, HNO2 dismutation yields •NO plus •NO2 and, depending on their redox potential, metal centers can either oxidize NO2− to •NO2 or catalyze the formation of •NO and N2O3 via NO2− reduction or reductive nitrosylation 16,19-21. The observations reported herein are unprecedented, in that we showed that NO2− participates in concerted nitration and nitrosation reactions at neutral pH in the absence of metal catalysis. We demonstrated that these reactions are stimulated by •NO autoxidation via the formation of the symmetrical isomer of N2O3 (ONONO, symN2O3). Additionally, by using both cell-based and murine models of inflammation, we provide evidence that symN2O3 is a physiologically-relevant signaling intermediate.

RESULTS

•NO mediates NO2−-dependent CLA nitration by macrophages

Conjugated linoleic acid is a preferential substrate for nitration in mice and in humans during both inflammatory conditions and digestive acidification. This is due to the unique reactivity of •NO2 with the external flanking carbons of the conjugated diene moiety, which is more reactive than bis-allylic fatty acids by a factor of 104–105 13. Activation of the murine macrophage-like cell line RAW 264.7 induced CLA nitration (Figure 1a). The addition of 15NO2− led to a dose-dependent increase in 15NO2-CLA and a concomitant decrease in 14NO2-CLA, indicating that NO2− is a significant source of •NO2 and that there is a competition between •NO-derived •14NO2 and 15NO2−-derived •15NO2 for CLA nitration. In these experiments, endogenous 14•NO was the only source of both 14•NO2 and 14NO2−. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) generation of •NO with 1400W abrogated both 14NO2-CLA and 15NO2-CLA formation, which was restored by the addition of the •NO donor deta-NONOate (Figure 1b-c). This indicated that •NO is required for cellular NO2−-dependent CLA nitration.

Figure 1. 15NO2− incorporation into NO2-CLA is dependent on •NO production by activated RAW264.7 cells.

a, CLA (50 μM) nitration by RAW264.7 cells activated with LPS and IFNγ for 24 h in the presence or absence of 15NO2−. Under these conditions, all 14•NO2 and 14NO2− is derived from endogenous 14•NO. *, # p<0.0001 versus 0 μM 15NO2− for 14NO2-CLA and 15NO2-CLA respectively. b, NO2-CLA formation by activated RAW264.7 cells in the presence of 1400W (100 μM). *, # p<0.0001 versus corresponding non-1400W treatments (in panel a) for 14NO2-CLA and 15NO2-CLA respectively. c, CLA nitration by 1400W-treated activated cells in the presence of deta-NONOate (200 μM). *,# p < 0.0001 versus corresponding 1400W alone treatment (in panel b). For all panels, data are mean ± SD (n=4) and two-way ANOVA plus Bonferroni's multiple comparison were used to test statistical significance.

CLA nitration by •NO and NO2− does not require cells

The oxidation of NO to •2 NO2 in vivo is typically viewed to be catalyzed by metal centers (e.g., ferryl-heme complexes) or low pH conditions, with neither reaction including a role for •NO 20,22,23. We next evaluated whether other cellular components, beyond iNOS-derived •NO, were required for NO2−-mediated CLA nitration. Incubation of CLA with the •NO-donor mahma-NONOate (MNO) in the absence of cells gave significant extents of 14NO2-CLA formation (Figure 2a), consistent with •NO2 generation from the reaction between •NO and dissolved O2 17. Analogous to data in Figure 1a, addition of 15NO2− dose-dependently decreased extents of 14NO2-CLA formation and increased 15NO2-CLA generation (Figure 2b-f). No CLA nitration occurred in the absence of •NO or when an aerobically-decayed •NO donor was added as a control, supporting that •NO2 generation via HNO2 disproportionation was negligible under these conditions (Figure 2g and Supplementary Results, Supplementary Fig. 1a). Similarly, we confirmed the absence of adventitious metal catalysis by treating our buffers with two different chelation strategies without affecting the yields of CLA nitration (Supplementary Figure 2). Although the individual rates of 14NO2-CLA and 15NO2-CLA formation were inversely modulated by 15NO2− (Supplementary Fig. 3a), the global rate and the total yield of NO2-CLA formation were only marginally affected (Figure 2g and Supplementary Fig. 3b).

Figure 2. 15NO2− participates in CLA nitration in the absence of cellular components.

Representative LCMS/MS traces for 14NO2-CLA (a) and 15NO2-CLA (b) detection. c-f, Kinetic traces of 14NO2-CLA and 15NO2-CLA formation from 25 μM MNO and 20 μM CLA in the absence (c) or presence of 20 μM (d), 200 μM (e) and 2 mM (f) 15NO2−. Data are representative traces generated by combining time-staggered replicate reactions (n=4). g, Total yields of NO -CLA formation versus 15NO2− concentration. Data are mean ± SD (n=4), * p < 0.05 versus 0 mM 15NO2− as determined by one way ANOVA and Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. No NO -CLA formation was detected from 2 mM 15NO2− in the absence of MNO.

Nitrite participates in •NO-dependent S-nitrosation

Nitric oxide autoxidation yields •NO2 which, in the presence of •NO, supports the generation of N2O3. Within this context, thiol nitrosation occurs either by direct reaction with N2O3 or via •NO2-dependent thiyl radical formation, followed by addition of •NO 17,24. Addition of 15NO2− to a system consisting of •NO, O2 and GSH not only supported the formation of GS14NO, but also dose-dependently yielded GS15NO (Figure 3a-f). No thiol nitrosation occurred in the absence of •NO, again ruling out HNO2 formation and dismutation in thiol nitrosation (Figures 3g and Supplementary Fig. 1b). Similar to CLA nitration, 15NO2− addition led to a dose-dependent increase in GS15NO, with no effect on net nitrosothiol yield (Figure 3g and Supplementary Fig. 4a-c). While NO2− nitrosates thiols and amines under acidic conditions, NO2−-dependent nitrosation reactions at neutral pH have only been previously detected upon metal center catalysis that often requires hypoxic conditions 23,25-27.

Figure 3. 15NO2− mediates glutathione nitrosation in the presence of •NO.

a-b, Representative LCMS/MS traces for GS14NO (a) and GS15NO (b) formation. c-f, Traces showing GS14NO and GS15NO formation from 2.5 μM MNO and 20 μM GSH in the absence (c) or presence of 20 μM (d), 200 μM (e) and 2 mM (f) 15NO2−. Traces are representative and reflect time-staggered replicate reactions (n=4). g, Total GSNO yields versus 15NO2− concentration. Data are mean ± SD (n=4), no statistical differences were found as determined by one way ANOVA. No GSNO was formed from 2 mM 15NO2− in the absence of MNO.

•NO2is needed for NO2−-mediated nitration and nitrosation

Decreasing O2 concentration (pO2 ≤ 10mmHg) and addition of the •NO2 scavenger potassium ferrocyanide (K4Fe(CN)6, k = 2×106 M−1s−1 17) inhibited both 14NO2-CLA and 15NO2-CLA production (Supplementary Fig. 5a-b). Similarly, these same conditions also inhibited the formation of GS14NO and GS15NO (Supplementary Fig. 5c-d), supporting a role for •NO2 in NO2−-dependent nitration and nitrosation reactions during •NO autoxidation.

Double isotope labeling reveals scrambling of NO2− atoms

The observation that 15N from 15NO2− was incorporated into both NO2-CLA and GSNO suggested that 15NO2− is oxidized by one electron to 15•NO2 during •NO autoxidation and that 15NO2− also supports the formation of 15N-containing nitrosating species. These observations motivated the hypothesis that 15NO2− reacts with •NO-derived nitrogen oxides to yield symN2O3 (2, Figure 4a). Unlike the asymmetrical isomer (asymN2O3, 1, Figure 4a), the nitrogen atoms in symN2O3 are bonded to a central oxygen via two equivalent bonds that will homolyze with identical probability. Alternative homolysis of these N-O bonds in 14•NO/15NO2−-derived symN2O3 would yield either 15•NO2 or 15•NO (2b and 2d, Figure 4a), thus providing a mechanism for explaining the incorporation of 15NO2−-derived 15N into both 15NO2-CLA and GS15 NO. In order to test this hypothesis, we utilized 15N- and 18O-labeled nitrite (15N18O2−) to differentiate between atoms coming from •NO autoxidation (14N, 16O) and those contributed exclusively by NO2−. This labeling strategy also reveals specifically symN2O3-derived atoms that yield mixed 14N/18O and 15N/16O isotopologues, such as 14N16O18O-containing •NO2 (2c, Figure 5a). Importantly, the different •NO2 and •NO isotopologues generated by symN2O3 homolysis can subsequently recombine with other •NO2 and •NO molecules giving rise to further isotopic scrambling and the formation of new isotopologues such as 15N18O16O2−, 15N16O16O- and 14N18O18O-containing •NO2, as well as 14N18O- and 15N16O-containing •NO.

Figure 4. NO2− incorporation into NO2-CLA and GSNO is associated with symN2O3 formation.

a, Scheme illustrating the asymmetrical (1) and symmetrical (2) conformations of N2O3. Arrows indicate alternative bond cleavage patterns. Whereas asymN2O3 homolysis produces a unique set of products (1a, 1b), alternative cleavage of the O-N-O bonds in symN2O3 can be evidenced by isotopic labeling (blue and red represent 14N and 16O respectively, dark blue and green are 15N and 18O). b, Distribution of NO2-CLA isotopologues versus 15N18O2− concentration in the presence of 25 μM MNO and 20 μM CLA. c, Isotopic GSNO distribution versus 15N18O2− in the presence of 2.5 μM MNO and 20 μM GSH. Data for panels b and c are mean ± SD (n=4). Error bars are not distinguishable as they overlap with data points.

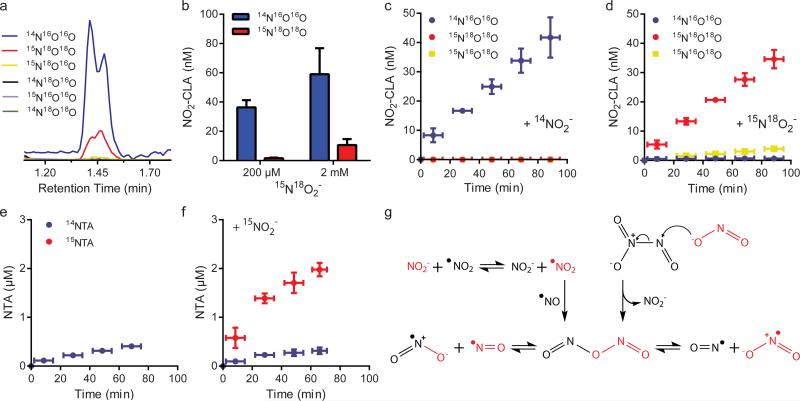

Figure 5. NO2− incorporation into nitrating and nitrosating equivalents requires reaction with • NO-derived species.

a, LC-MS/MS trace showing the formation of 14NO2-CLA and 15N18O2-CLA from CLA (20 μM) nitration by pure •NO gas in the presence of 2 mM 15N18O2−. b, NO2-CLA yields obtained from CLA nitration by •NO gas and 15N18O2−. Data are means ± SD (n=3). c-d, NO2-CLA formation from the reaction between 50 μM NOBF and either 14NO2− (c) or 15N18O2− (d) in acetonitrile. Data are mean ± SD (n=4), with no NO2-CLA formation observed in the absence of nitrite. e-f, NTA formation from the reaction between 20 μM DAN and 50 μM NOBF4 in the absence (e) or presence (f) of 20 μM 15NO2− 2in acetonitrile. Data are means ± SD (n=4). g, Proposed mechanisms for NO2− incorporation into nitrating and nitrosating species via symN2O3 formation.

15N18O2-derived atoms were incorporated into NO2-CLA primarily as mixed isotopologues at low 15N18O2− concentrations (14N18O16O-CLA and 15N18O16O-CLA), but became more extensively incorporated to form 15N18O2-CLA when the concentration of 15N18O2− was increased (Figure 4b). Similar results were obtained when we added 15N18O2− to GSH in the presence of •NO and O2, with lower 15N18O2− concentrations yielding mixed GSNO isotopologues and higher concentrations supporting more extensive formation of GS15N18O (Figure 4c). While •NO concentration had a minor effect on the relative yields of NO2-CLA isotopologues, 15N18O2− incorporation into GSNO was favored at higher •NO concentrations, consistent with a predominant role for N2O3-mediated nitrosation under these conditions (Supplementary Fig. 6) 3.

N2O3 participates in NO2−-mediated nitration reactions

The preceding results indicated that NO2− incorporation into NO2-CLA and GSNO involved symN2O3. To assess whether N2O3 formation is required for NO2− incorporation into NO2-CLA, we evaluated direct CLA nitration by •NO2 gas and 15N18O2− in the absence of •NO. While •NO2 mediated substantial NO2-CLA formation, only a minor fraction of the products incorporated 15N18O2−-derived atoms and no mixed isotopologues were detected (Figure 5a-b). Comparison of the relative yields of NO2−- derived NO2-CLA in the presence (Figure 2e-f) or absence of •NO (Figure 5b), indicated that the role of •NO in NO2−-dependent nitration extends beyond •NO2 formation. Additionally, we ruled out a potential role for NO2+ in CLA nitration under our experimental conditions by using nitronium tetrafluoroborate NO2BF4 as a nitrating agent (Supplementary Fig. 7). These results are consistent with previous reports indicating that NO2+ is an extremely short-lived species in aqueous solution due to preferential reaction with OH− to generate NO3− 28,29.

Next, we utilized nitrosonium tetrafluoroborate (NOBF4) as a •NO-independent source of nitrosating equivalents (NO+) in organic solvent to test the possibility that NO2−-derived N2O3 formation supports the incorporation of NO2− atoms into NO2-CLA. While NOBF4 failed to induce CLA nitration per se, the further addition of 14NO2− led to substantial 14NO2-CLA formation (Figure 5c). Also, addition of 15N18O2− to NOBF4 resulted not only in 15N18O2-CLA generation but also yielded the mixed isotopologue 15N16O18O-CLA, consistent with symN2O3 formation upon NO2− nitrosation (Figure 5d). Further support for the formation of symN2O3 from the reaction between NO2− and NOBF4 was obtained by following 2,3-diaminonaphtalene (DAN) nitrosation to 2,3-naphtotriazole (NTA). We utilized DAN in lieu of GSH due to the poor solubility of GSH in non-aqueous solvents. As expected, NOBF4 mediated only 14NTA formation in the absence of 15NO2− (Figure 5e). Addition of 15NO2− to NOBF4 significantly increased 15NTA yields, consistent with the notion that NO2− nitrosation led to symN2O3 formation (Figure 5f). Figure 5g shows alternative mechanisms for symN2O3 formation from NO2−.

NO2−-derived symN2O3 is generated during inflammation

To test whether symN2O3 formation occurs in vivo, we induced inflammation in mice by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of LPS, followed by i.p. administration of CLA (2.5 mg) +/− 15N18O2− 18 h later. This model caused an extensive influx of inflammatory monocytes and neutrophils which, together with a minor dendritic cell population, promoted increased generation of iNOS-derived secondary reactive species in the peritoneal cavity (Supplementary Fig. 8). Importantly, the doses of 15N18O2− utilized for these experiments (20 and 200 nmol) were well within the range of concentrations that are protective in animal models of ischemia and reperfusion injury 30. Furthermore, analysis of NO2− levels at the time of peritoneal lavage showed that exogenously-added 15N18O2− represented less than 10 % of the total endogenous concentration of this anion (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, both 14N16O2-CLA and 15N18O2−-derived isotopologues were detected (Figure 6a-c). The dose-dependent formation of 15N18O16O, 14N18O16O and 15N16O16O-containing NO2- CLA isotopologues recapitulated the in vitro responses (Figure 4b and S4c), indicating that biologically generated •NO and •NO2 promote 15N18O2− incorporation into symN2O3 in vivo (Figure 6b-c and e-f). The atomic composition of each individual species was unequivocally confirmed by high resolution hybrid FT-MS (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 2). A drop in peritoneal pH during inflammation could potentially affect nitration by symN2O3. In this regard, inflammation results in a slight pH decrease in the peritoneal cavity, with values changing from 7.41 to 7.29 in humans, 7.32 to 7.19 in cats, and remaining unaltered in dogs (no data available for rodents) 31,32. In this regard, we observed a decrease in the yield of in vitro CLA nitration resulting from •NO autoxidation in the presence of 15N18O2− at pH values below 7.0. Importantly, the distribution of NO2-CLA isotopologues was not affected across the pH interval, suggesting no direct effect of pH on symN2O3 formation (Supplementary Fig. 10). Finally, we recapitulated these results using the short half-life (less than 2 s) •NO donor proli- NONOate, affirming that the decrease in NO2-CLA formation observed at lower pH was not due to changes in the rate of •NO release.

Figure 6. Inflammatory conditions promote NO2−-dependent symN2O3 generation in vivo.

a-c, Total concentrations and relative isotopic distributions of NO2-CLA generated during peritoneal inflammation. Points represent measurements from individual animals with mean ± SD indicated by the lines. Mice were injected i.p. with 20 μg LPS and 18 h later received a second injection containing 2.5 mg CLA plus 0 (a), 20 (b) or 200 (c) nmol 15N18O2−. d-f, Representative LC-MS/MS traces of NO2-CLA isotopologue formation after administration of 0 (d), 20 (e) and 200 (f) nmol 15N18O2−. 14N18O16O-containing NO2-CLA levels were <0.5% of total and were not included in the isotopic distributions (a-c), 14N18O18O-containing NO2-CLA was not detected.

DISCUSSION

Nitrite, firmly established as a metastable physiologic •NO reserve, is also a source of nitrosating and nitrating intermediates that expand the scope of mechanisms and secondary mediators that can transduce cell signaling events mediated by redox reactions 33,34. In accordance with this concept, 15NO2− addition to activated macrophages induced 15NO-CLA formation in a dose-dependent manner. The relative contributions of different cell compartments to fatty acid nitration have not been characterized, as many of the reactive species involved in this process, -including both the substrate CLA and the resulting NO2-CLA, are readily diffusible and membrane permeable. However, the observed yields and kinetic profiles of CLA nitration by activated macrophages suggested that the free fatty acid, rather than esterified species, was the substrate for NO2-CLA formation under the present conditions. Importantly, inhibition of •NO synthesis abrogated both 14NO2-CLA and 15NO2-CLA generation, revealing an essential role for •NO in CLA nitration by 15NO2−. While the acidification of NO2− (pKa 3.46) in compartments such as the stomach, mitochondrial intermembrane space or phagolysosomes, favors the generation of HNO2 and secondary species, current perspective holds that NO2−-mediated nitration and nitrosation reactions at neutral pH is otherwise the consequence of metal catalysis 16,19-21,23,25. Herein, we report the novel concept that NO2− participates in •NO autoxidation-mediated nitration and nitrosation reactions at neutral pH in the absence of cellular constituents and adventitious metals.

The incorporation of 15N into both NO2-CLA and GSNO during •NO autoxidation indicated that 15NO2− not only generates a nitrating species, but also forms either 15•NO or a species capable of direct 15N-nitroso transfer. A potential explanation involves the initial oxidation of 15NO2− to 15•NO2, followed by reaction with 14•NO to generate 15N14N-containing N2O3. The most commonly-cited structure for N2O3 entails an asymmetrical conformation with nitrosyl and nitryl moieties connected by a weak N-N bond 35. However, homolytic scission of this bond would regenerate 14•NO and 15•NO2, and direct N2O3 reaction with a thiol would mediate 14N-nitroso transfer via concerted nucleophilic substitution. These latter reactions did not explain the formation of GS15NO from 15NO2−. While asymN2O3 is the most stable candidate intermediate structure, alternative N2O3 conformations have been detected in low-temperature matrices and liquid xenon 36-38, including a symmetrical species in which two equivalent nitroso groups are connected to a central oxygen via identical N-O bonds. The stochastic cleavage of the internal N-O bonds in symN2O3 generated from 15•NO2 and 14•NO, would lead to random distribution of the 15N-atom. In other words, symmetrical 14N,15N N2O3 is equally able to generate 14•NO or 15•NO, thus accounting for 15NO2−-derived GS15NO formation.

Symmetrical N2O3 is only marginally less stable than the asymmetrical isomer 37-41. It has been predicted that symN2O3 represents a proportion of total N2O3 under physiological conditions, and symN2O3 has been proposed as an obligatory intermediate in the generation of asymN2O3 5,42. Herein, the aqueous neutral pH reactions of 15N18O2− yielded not only purely •NO (14N/16O) and 15N18O2−-derived products, but also mixed 14N/18O and 15N/16O isotopologues (Figure 4). This indicated that the reaction between NO2− and species generated during •NO autoxidation entails more than a mere electron exchange and rather point at the formation of a covalent intermediate involving •NO- and NO2−-derived atoms. Furthermore, the distribution of GSNO and NO2-CLA isotopologues supported that NO2− is a precursor for symN2O3 formation during •NO autoxidation. Consistent with the canonical mechanism for •NO autoxidation (Reactions 1-4), lower O2 tensions and K4Fe(CN)6 supplementation decreased yields of both •NO- and 15NO2−-derived NO2CLA and GSNO, indicating •NO2 as an intermediate in these reactions 24,43. It is possible that •NO autoxidation does not yield “free” •NO2, but rather produces an unidentified NOx intermediate capable of both oxidizing K4Fe(CN)6 and nitrosating thiols 18,44. The present report, showing NO2-CLA formation during •NO autoxidation, implicates •NO2 as the proximal nitrating species but does not exclude the possibility that symN2O3 could also directly mediate CLA nitration 45.

Two mechanisms can be envisaged by which NO2− gives rise to symN2O3; either NO2− oxidation to •NO2 followed by reaction with •NO or a direct nucleophilic substitution (Figure 5g). Either mechanism is consistent with the observed dose-dependent increase in isotopic incorporation of 15NO2− where net product yields are similar (Figures 2 and 3). The formation of 15N18O2-CLA (Figure 5a-b) indicated that 14•NO2 gas oxidizes 15N18O2− to 15•N18O2 46. However, the lower relative yields of 15N18O2-CLA obtained using •14NO2 gas versus •14NO/O2 indicated that •NO promotes NO2− incorporation into NO2-CLA to a greater extent than when electron self-exchange occurs between NO2− and •NO2 gas. A role for nitrosodioxyl radical (ONOO•) generated during •NO autoxidation in NO2− oxidation to •NO2 is unlikely, as this reaction is thermodynamically unfavorable (•NO2/NO2− E° = +1.04 V vs. NHE and ONOO•/ONOO- E° = +0.511 V vs. NHE 46-49). An additional mechanism for NO2− incorporation into N2O3 involves a substitution reaction in which a nucleophilic atom in NO2− attacks the nitroso moiety in •NO/O2-derived N2O3. The conformation of the resulting N2O3 could be either asymmetrical or symmetrical, depending on whether the nucleophilic attack is mediated by nitrogen or oxygen atoms, respectively.

To further assess the role of N2O3 in the formation of nitration and nitrosation products, we used NOBF4 as a •NO-independent source of nitrosating equivalents. While this reaction system departs from biological conditions, it adds perspective to the concept of N2O3 generation occurring via NO2− nitrosation. No NO2-CLA was formed from NOBF4 alone, however addition of 15N18O2− yielded not only 15N18O2-CLA but also the mixed 15N16O18O isotopologue, supporting that •NO2 was formed secondary to NO2− nitrosation (Figure 5d). Additionally, while NOBF4 was sufficient to induce 14NTA formation, 15NO2− addition led to 15NTA production, consistent with the formation of an intermediate species capable of 15N-nitroso transfer. In aggregate, these results indicated that 15NO2− nitrosation generates a symN2O3 intermediate that can mediate the incorporation of 15N into both nitrated and nitrosated products.

Inflammatory responses are associated with increased production of reactive species capable of mediating oxidation, nitration and nitrosation reactions 50. To test whether these species can induce symN2O3 formation from NO2− in a biological milieu, we analyzed CLA nitration products during acute inflammation in a murine model of peritonitis. There was significant CLA nitration induced by endogenously-generated •NO2, as indicated by the detection of 14N16O NO2-CLA in peritoneal lavage (Figure 6). Notably, the administration of 15N18O2− revealed dose-dependent generation of not only 15N18O18O-CLA, but also the scrambled isotopologues 15N18O16O-, 14N18O16O- and 15N16O16O-CLA. This indicated that endogenouslygenerated reactive species mediate NO2− incorporation into symN2O3 in vivo. Importantly, whereas different metal-dependent and -independent nitration mechanisms might be simultaneously operative in vivo, data from metal-free reaction systems indicated that NO2− -derived symN2O3 formation does not require either metal centers or additional cell-derived components.

The discovery that NO2− supports the generation of both electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkenes and nitrosothiols in vivo provides new perspective for understanding the broad array of cell signaling and physiological responses that can be instigated by NO2− 13,33. The present in vitro and in vivo evidence also reveals a novel role for NO2− in the concerted generation of nitrating and nitrosating intermediates via the formation and stochastic homolysis of symN2O3.

ONLINE METHODS

Materials

9,11-Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA, 90%) was obtained from Nu-Check Prep, Inc (Elysian, MN, USA). 15N16O2 (98%) and 15N18O2 (15N, 98%; 18O, 90%) sodium nitrite were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA, USA). 1400W, deta-NONOate and mahma-NONOate (MNO) were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). 13C18-nitro-oleic acid was synthesized in house 51. Chemical characterization of the 13C18-nitro-oleic acid batch utilized herein was not different from previously published reports 51. All other chemicals were of analytical grade and were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Animals were housed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). All procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval # 14084265).

CLA nitration by RAW264.7 cells

Cells were maintained in DMEM (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) plus 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco-Life Technologies, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37 °C, 95 % air and 5 % CO2. Cells were treated with 50 μM CLA, 100 ng/mL LPS and 200 U/mL IFNγ, and incubated with or without 100 μM 1400W plus or minus 200 μM deta-NONOate in DMEM plus 1 % FBS. Media was collected at 24 h, spiked with internal standard (10 pmoles), and NO2-CLA extracted using C18 SPE columns (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as described previously 14.

Nitration and nitrosation reactions

CLA, 2,3-diaminonaphtalene (DAN) or glutathione (GSH), (20 μM) were incubated with MNO (25 μM for nitration and 2.5 μM for nitrosation reactions respectively) and NO2− (0 - 2 mM) in the presence or absence of K4Fe(CN)6 (1 mM) in 20 mM BisTris pH 7.0 containing 100 μM DTPA. Experiments using NOBF4 were performed in acetonitrile to prevent reagent hydrolysis. Reactions were started by quick addition of a reaction mixture to 2 mL vials containing 10 μL of a 200x MNO stock solution. Vials were filled to capacity to eliminate headspace, sealed and immediately placed in an HPLC autosampler at 25 °C. Kinetic profiles were obtained by repeated injection of the reaction mixtures in a LCMS/MS system. For experiments in which Proli-NONOate was used, 10 μL of a 200x stock was added to sealed vials filled to capacity using a Hamilton syringe. Quantification of NO2-CLA, S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) and 2,3-naphtotriazole (NTA) was performed using calibration curves prepared from either synthetic or commercially-available standards. 13C-nitro-oleic acid, 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid (PIPES) and caffeine were utilized as internal standards for NO2-CLA, GSNO and NTA quantification respectively. Low-oxygen experiments were performed in a hypoxic chamber (COY Lab Products, Grass Lake, MI, USA).

CLA nitration with •NO2gas

CLA (20 μM) and 15N18O2− (200 μM, 2 mM) in 20 mM BisTris buffer pH 7.0 containing 100 μM DTPA were exposed to humidified •NO2 gas (10.4 ±0.2 ppm in air, less than 0.1 ppm •NO) for 30 min at 160 mL/min under constant stirring in the dark. NO2-CLA formation was measured by LC-MS/MS.

Peritoneal inflammation model

Male C57BL/6J mice, aged 10-12 weeks, were injected intraperitoneally with 20 μg LPS (6×104 endotoxin units) dissolved in a saline plus Freund's incomplete adjuvant (1:1) vehicle. Freund's incomplete adjuvant was utilized in conjunction with LPS to create an emulsion and induce localized, sustained inflammation in the peritoneum. This response relies on toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activation by LPS, an approach that was preferred over the more general and painful inflammation caused by the inactivated M. tuberculosis present in the complete adjuvant. Mice were rested overnight and subsequently treated with 2.5 mg CLA plus 0-200 nmol Na15N18O2− in a phosphate buffered saline (PBS)/polyethylene glycol-400 vehicle 18 h post-LPS challenge. Mice were killed 1 h later and peritoneal lavage performed using PBS containing 2 mM EDTA. Lavagate was centrifuged and the cell-free supernatant extracted by C18 solid phase extraction (SPE) columns to enrich fatty acids and remove salts, followed by nitrated fatty acid purification with aminopropyl SPE columns. Briefly, C18 eluates were dried and resuspended in hexane:methyl tert-butyl ether:acetic acid (100:3:0.3) and loaded into hexane- equilibrated aminoproyl SPE columns. Non-polar complex lipids were removed with chloroform:isopropanol (2:1) followed by free fatty acid elution with diethyl ether:acetic acid (196:4). Nitrated fatty acids in the polar lipid fraction were measured by LC-MS/MS as described below.

Peritoneal NO2− measurement

Total NO2− levels were determined in peritoneal lavages by ozone-based I3− reductive chemiluminescence as described 52. To differentiate exogenous 15N- versus endogenous 14N-containing nitrite, DAN diazotization to either 14NTA or 15NTA was determined by LC-MS/MS. Briefly, peritoneal lavagate dilutions were reacted with 30 μM DAN under acidic conditions for 10 min followed by alkalinization by sodium hydroxide addition to stop the reaction and LC-MS/MS analysis.

Analysis of peritoneal cell populations

Cell subpopulations in the peritoneal lavage were identified by flow cytometry analysis via staining with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against the following antigens: Ly-6G, MHC II, CD11c, F4/80, CD11b, CD86 (eBioscience). For iNOS expression analysis, cells were fixed and permeabilized with Fix/Perm Buffer (BD Biosciences) and stained with mouse anti-iNOS (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and PE-anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab). Samples were acquired using a LSRII flow cytometer (BD) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

LC-MS/MS analysis

Nitrated fatty acid samples from in vitro experiments were resolved by C18 reverse-phase chromatography (Gemini 2 × 20 mm, 3 μm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) using 10 mM ammonium acetate/acetonitrile mobile phase system. Samples were loaded at 35 % acetonitrile at 0.75 mL/min, maintained for 0.2 min and the organic phase was increased to 90 % over 2 min. The column was then washed with 100 % acetonitrile for 1.2 min and reequilibrated at 35 % for an additional 0.8 min. Nitrated fatty acids extracted from cell media and peritoneal lavage were resolved with an analytical C18 Luna column (2 × 100 mm, 5 μm particle size; Phenomenex) at a 0.65 ml/min flow rate and an acetonitrile/water mobile phase system in the presence of 0.1 % acetic acid. Samples were loaded at 35 % acetonitrile/acetic acid for 1 min, followed by a linear increase in the organic phase to 90 % over 8 min. The column was then washed with 100 % acetonitrile/acetic acid for 3 min and re-equilibrated at 35 % for 3 min. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed using either an API 5000 or an API Qtrap 4000 (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA) in the negative ion mode using the following settings: source temperature 650 °C, curtain gas: 50, ionization spray voltage: -4500, GS1: 55, GS2: 50, declustering potential: −70 V, entrance potential: −4 V, collision energy: −35 V and collision cell exit potential: −5 V. The following MRM transitions were used for NO2-CLA detection: 14N16O2 (324.2/46), 15N16O2 (325.2/47), 14N16O18O (326.2/48), 15N16O18O (327.2/49), 14N18O18O (328.2/50), 15N18O18O (329.2/51), and 13C18 NO2-OA (344.2/46). For GSNO measurements, samples were loaded in a Hypercarb column (2.1 × 100 mm, 5 μm, Thermo Scientific) at 5 % acetonitrile using the same mobile phase as above; organic phase percentage was maintained for 0.3 min and then increased to 70 % within 2.2 min. The column was washed with 100% acetonitrile for 0.7 min and then re-equilibrated for 0.7 min. MS analysis was performed in the positive ion mode at 550 °C, curtain gas 40, IS voltage 5500, GS1: 50, GS2: 50, DP: 40 V, EP: 9 V, CE: 13V and CXP: 9 V. For the internal standard, DP was 110 V, EP 10 V, CE 37 V and CXP 13 V. GSNO was detected using the following transitions: 14N16O (337.3/307.3), 15N16O (338.3/307.3), 14N18O (339.3/307.3), 15N18O (340.3/307.3) and PIPES (303.2/152.2). Finally for DAN nitrosation reactions, samples were loaded on a Gemini C18 column at 5 % acetonitrile/95 % 10 mM ammonium acetate. The organic phase was held constant for 0.3 min and then increased to 75 % over the next 2.3 min. The column was washed with 100 % organic phase for 0.7 min and then re-equilibrated for 0.7 min. NTA was measured in the positive ion mode at 650 °C, curtain gas: 40, IS voltage: 5500, GS1: 55, GS2: 50, DP: 70 V, EP: 5 V, CE: 35 V and CXP: 5 V. For the internal standard DP was set at 80 V, EP at 10 V and CE at 27 V. MRM transitions were: 14NTA (170.1/115.1), 15NTA (171.1/115.1) and caffeine (195.3/138.1).

High resolution mass spectrometric characterization of inflammation-derived NO2-CLAisotopologues

Analytes of interest were characterized in both collision-induced dissociation (CID) and high collision energy dissociation (HCD) modes using an LTQ Velos Orbitrap (Velos Orbitrap, Thermo Scientific) equipped with a HESI II electrospray source. The following parameters were used: source temperature 450 °C, capillary temperature 360 °C, sheath gas flow 20, auxiliary gas flow 15, sweep gas flow 3, Ion spray voltage 4 kV, S-lens RF level 41 (%). The instrument FT-mode was calibrated using the manufacturer's recommended calibration solution with the addition of malic acid as a low m/z calibration point in the negative ion mode. For MS/MS analysis of isotopologues, a window of 8 amu was selected for fragmentation, as isolation of individual isotopologues would not provide the necessary discrimination in the ion trap needed for these experiments. MS/MS analysis was performed at 60,000 resolution where discrimination of individual isotopologues (15N, 13C and 18O) was achieved.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA. USA) version 6.05 by one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni multiple comparison test as indicated in the figure legends. P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH grants R01-HL058115, R01-HL64937, P30-DK072506, P01-HL103455 (BAF), R01-AT006822 (FJS) and AHA #14GRNT20170024 (FJS). We thank Drs. Mark T Gladwin, Jesus Tejero, Ana Maria Ferreira and Beatriz Alvarez for helpful discussions and Dr. Tim Sparwasser for expert assistance with flow cytometry experiments.

Abbreviations

- 1400W

N-[[3-(aminomethyl)phenyl]methyl]-ethanimidamide, dihydrochloride

- BisTris

2,2-bis(hydroxymethyl)-2,2′,2″-nitrilotriethanol

- 13C18-nitro-oleic acid

10-nitro-octadec-9-enoic acid

- CLA

(9Z,11E)-octadecadienoic acid

- DAN

2,3-diaminonaphtalene

- Deta-NONOate

2,2′-(Hydroxynitrosohydrazino)bis-ethanamine

- DTPA

diethylene-triaminepentaacetic acid

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- GSNO

S-nitroso-L-glutathione

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- LC-MS/MS

high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry

- LPS

lipopolysaccharyde

- MNO

mahma-NONOate, (Z)-1-[N-methyl-N-[6-(N-methylammoniohexyl)amino]]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- NO2-CLA

conjugated nitro-linoleic acid, mixture of positional isomers of 9- and 12-nitrooctadeca-9,11-dienoic acid

- •NO2

nitrogen dioxide

- •NO

nitrogen monoxide

- NOBF4

nitrosonium tetrafluoroborate

- NO2BF4

nitronium tetrafluoroborate

- HNO2

nitrous acid

- NTA

2,3-naphtotriazole

- PIPES

1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid

- Proli-NONOate

1-[(2-carboxylato)pyrrolidin-1-yl]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate

- SPE

solid phase extraction

- TLR4

toll-like receptor 4

Footnotes

Author contributions: DAV designed, performed and analyzed experiments, as well as wrote the manuscript. LM designed, performed and analyzed cell-based experiments. SRS performed high resolution LC-MS/MS experiments and contributed to overall LC-MS/MS method development. EMP designed and performed •NO2 gas experiments. MF developed extraction methods for in vivo experiments. GFS contributed to data interpretation. JRL designed experiments, contributed to data interpretation and provided critical insight into manuscript content. BAF contributed to the overall concept, experimental design and manuscript preparation. FJS designed experiments, contributed to data analysis and interpretation as well as manuscript writing.

Competing Financial Interests Statement: BAF and FJS acknowledge financial interest in Complexa, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maron BA, Tang SS, Loscalzo J. S-nitrosothiols and the S-nitrosoproteome of the cardiovascular system. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:270–287. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosworth CA, Toledo JC, Jr., Zmijewski JW, Li Q, Lancaster JR., Jr. Dinitrosyliron complexes and the mechanism(s) of cellular protein nitrosothiol formation from nitric oxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4671–4676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710416106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lancaster JR., Jr. Protein cysteine thiol nitrosation: maker or marker of reactive nitrogen species-induced nonerythroid cellular signaling? Nitric Oxide. 2008;19:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moller MN, et al. Membrane “lens” effect: focusing the formation of reactive nitrogen oxides from the *NO/O2 reaction. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:709–714. doi: 10.1021/tx700010h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nedospasov AA. Is N2O3 the main nitrosating intermediate in aerated nitric oxide (NO) solutions in vivo? If so, where, when, and which one? J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2002;16:109–120. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broniowska KA, Keszler A, Basu S, Kim-Shapiro DB, Hogg N. Cytochrome c-mediated formation of S-nitrosothiol in cells. Biochem J. 2012;442:191–197. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster MW, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster MW, et al. Proteomic characterization of the cellular response to nitrosative stress mediated by s-nitrosoglutathione reductase inhibition. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:2480–2491. doi: 10.1021/pr201180m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Souza JM, Peluffo G, Radi R. Protein tyrosine nitration--functional alteration or just a biomarker? Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akaike T, Nishida M, Fujii S. Regulation of redox signalling by an electrophilic cyclic nucleotide. J Biochem. 2013;153:131–138. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delmastro-Greenwood M, Freeman BA, Wendell SG. Redox-dependent anti-inflammatory signaling actions of unsaturated Fatty acids. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:79–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schopfer FJ, Cipollina C, Freeman BA. Formation and signaling actions of electrophilic lipids. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5997–6021. doi: 10.1021/cr200131e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonacci G, et al. Conjugated linoleic acid is a preferential substrate for fatty acid nitration. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:44071–44082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salvatore SR, et al. Characterization and quantification of endogenous fatty acid nitroalkene metabolites in human urine. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:1998–2009. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M037804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charles RL, et al. Protection from hypertension in mice by the Mediterranean diet is mediated by nitro fatty acid inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8167–8172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402965111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E. Biology of nitrogen oxides in the gastrointestinal tract. Gut. 2013;62:616–629. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein S, Czapski G. Kinetics of Nitric-Oxide Autoxidation in Aqueous-Solution in the Absence and Presence of Various Reductants - the Nature of the Oxidizing Intermediates. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:12078–12084. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wink DA, Darbyshire JF, Nims RW, Saavedra JE, Ford PC. Reactions of the bioregulatory agent nitric oxide in oxygenated aqueous media: determination of the kinetics for oxidation and nitrosation by intermediates generated in the NO/O2 reaction. Chem Res Toxicol. 1993;6:23–27. doi: 10.1021/tx00031a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Faassen EE, et al. Nitrite as regulator of hypoxic signaling in mammalian physiology. Med Res Rev. 2009;29:683–741. doi: 10.1002/med.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Vliet A, Eiserich JP, Halliwell B, Cross CE. Formation of reactive nitrogen species during peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of nitrite. A potential additional mechanism of nitric oxide-dependent toxicity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7617–7625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford PC. Reactions of NO and nitrite with heme models and proteins. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:6226–6239. doi: 10.1021/ic902073z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castro L, Eiserich JP, Sweeney S, Radi R, Freeman BA. Cytochrome c: a catalyst and target of nitrite-hydrogen peroxide-dependent protein nitration. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;421:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.d'Ischia M, Napolitano A, Manini P, Panzella L. Secondary targets of nitrite-derived reactive nitrogen species: nitrosation/nitration pathways, antioxidant defense mechanisms and toxicological implications. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:2071–2092. doi: 10.1021/tx2003118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein S, Czapski G. Mechanism of the Nitrosation of Thiols and Amines by Oxygenated•NO Solutions: the Nature of the Nitrosating Intermediates. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3419–3425. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basu S, et al. Catalytic generation of N2O3 by the concerted nitrite reductase and anhydrase activity of hemoglobin. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:785–794. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandez BO, Ford PC. Nitrite catalyzes ferriheme protein reductive nitrosylation. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10510–10511. doi: 10.1021/ja036693b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tejero J, et al. Low NO concentration dependence of reductive nitrosylation reaction of hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18262–18274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.298927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beckman JS, et al. Kinetics of superoxide dismutase- and iron-catalyzed nitration of phenolics by peroxynitrite. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:438–445. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90432-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ischiropoulos H, et al. Peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration catalyzed by superoxide dismutase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:431–437. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90431-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duranski MR, et al. Cytoprotective effects of nitrite during in vivo ischemia-reperfusion of the heart and liver. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1232–1240. doi: 10.1172/JCI22493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonczynski JJ, Ludwig LL, Barton LJ, Loar A, Peterson ME. Comparison of peritoneal fluid and peripheral blood pH, bicarbonate, glucose, and lactate concentration as a diagnostic tool for septic peritonitis in dogs and cats. Vet Surg. 2003;32:161–166. doi: 10.1053/jvet.2003.50005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sennesael JJ, De Smedt GC, Van der Niepen P, Verbeelen DL. The impact of peritonitis on peritoneal and systemic acid-base status of patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 1994;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vitturi DA, Patel RP. Current perspectives and challenges in understanding the role of nitrite as an integral player in nitric oxide biology and therapy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kansanen E, Jyrkkanen HK, Levonen AL. Activation of stress signaling pathways by electrophilic oxidized and nitrated lipids. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:973–982. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horakh J, Borrmann H, Simon A. Phase-Relationships in the N2O3/N2O4 System and Crystal-Structures of N2O3. Chem Eur J. 1995;1:389–393. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fateley WG, Bent HA, Crawford B. Infrared Spectra of the Frozen Oxides of Nitrogen. J Chem Phys. 1959;31:204–217. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holland RF, Maier WB. Infrared absorption spectra of nitrogen oxides in liquid xenon. Isomerization of N2O3 a). J Chem Phys. 1983;78:2928–2941. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varetti EL, Pimentel GC. Isomeric Forms of Dinitrogen Trioxide in a Nitrogen Matrix. J Chem Phys. 1971;55:3813–3821. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw AW, Vosper AJ. Dinitrogen trioxide. Part IX. Stability of dinitrogen trioxide in solution. J Chem Soc A. 1971:1592. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jubert AH, Varetti EL, Villar HO, Castro EA. A theoretical study of the relative stability of the isomeric forms of N2O3. Theor Chim Acta. 1984;64:313–316. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun Z, Liu YD, Lv CL, Zhong RG. Theoretical investigation of the isomerization of N2O3 and the N-nitrosation of dimethylamine by asym-N2O3, sym-N2O3, and trans–cis N2O3 isomers. J Mol Struct (Theochem) 2009;908:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zakharov II, Zakharova OI. Nitrosonium Nitrite Isomer of N2O3: Quantum-Chemical Data. J Struct Chem. 2009;50:212–218. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pryor WA, Lightsey JW, Church DF. Reaction of nitrogen dioxide with alkenes and polyunsaturated fatty acids: addition and hydrogen-abstraction mechanisms. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6685–6692. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wink DA, et al. Reaction kinetics for nitrosation of cysteine and glutathione in aerobic nitric oxide solutions at neutral pH. Insights into the fate and physiological effects of intermediates generated in the NO/O2 reaction. Chem Res Toxicol. 1994;7:519–525. doi: 10.1021/tx00040a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wink DA, Ford PC. Nitric Oxide Reactions Important to Biological Systems: A Survey of Some Kinetics Investigations. Methods. 1995;7:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huie RE. The reaction kinetics of NO2(.). Toxicology. 1994;89:193–216. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(94)90098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galliker B, Kissner R, Nauser T, Koppenol WH. Intermediates in the autoxidation of nitrogen monoxide. Chemistry. 2009;15:6161–6168. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amatore C, et al. Characterization of the electrochemical oxidation of peroxynitrite: Relevance to oxidative stress bursts measured at the single cell level. Chem Eur J. 2001;7:4171–4179. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20011001)7:19<4171::aid-chem4171>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koppenol WH. Nitrosation, thiols, and hemoglobin: energetics and kinetics. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:5637–5641. doi: 10.1021/ic202561f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Gelhaus SL, Schopfer FJ. Nitrated fatty acids: synthesis and measurement. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;59:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lang JD, Jr., et al. Inhaled NO accelerates restoration of liver function in adults following orthotopic liver transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2583–2591. doi: 10.1172/JCI31892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.