Abstract

Study Design

A cross-sectional, descriptive study.

Purpose

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between kyphosis and lordosis measured by using a flexible ruler and musculoskeletal pain in students of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

Overview of Literature

The spine supports the body during different activities by maintaining appropriate body alignment and posture. Normal alignment of the spine depends on its structural, muscular, bony, and articular performance.

Methods

Two hundred forty-one students participated in this study. A single examiner evaluated the angles of lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis by using a flexible ruler. To determine the severity and frequency of pain in low-back and inter-scapular regions, a tailor-made questionnaire with visual analog scale was used. Finally, using the Kendall correlation coefficient, the data were statistically analyzed.

Results

The mean value of lumbar lordosis was 34.46°±12.61° in female students and 22.46°±9.9° in male students. The mean value of lumbar lordosis significantly differed between female and male students (p<0.001). However, there was no difference in the level of the thoracic curve (p=0.288). Relationship between kyphosis measured by using a flexible ruler and inter-scapular pain in male and female students was not significant (p=0.946). However, the relationship between lumbar lordosis and low back pain was statistically significant (p=0.006). Also, no significant relationship was observed between abnormal kyphosis and frequency of inter-scapular pain, and between lumbar lordosis and low back pain.

Conclusions

Lumbar lordosis contributes to low back pain. The causes of musculoskeletal pain could be muscle imbalance and muscle and ligament strain.

Keywords: Kyphosis, Lordosis, Pain

Introduction

Spine with a lateral S-shaped curve is an important component of the body skeleton. This structure supports the body during different activities by maintaining appropriate body alignment and posture [1,2].

Normal alignment of the spine depends on its structural, muscular, bony, and articular performance; therefore, weakness of the spinal muscles can lead to static and dynamic imbalances of the body which are generally called positional abnormalities [2]. Skeletal abnormalities result from lack of motion and inappropriate movement patterns, which have undesirable effects on the psychological, social, and physiological function [3].

Hyperkyphosis or postural round back is a common spinal deformity with a prevalence of 15.3% in Western societies [3] and 13.2% in Iranian high school students [4]. Congenital anomalies, neuro-muscular disorders, Scheuermann disease, and positional difficulties play an important role in causing thoracic kyphosis. Increasing the arch of the thoracic spine known as kyphosis along with the shortening of the thoracic muscles and weakness of the respiratory muscles affect the pulmonary system by decreasing the thoracic volume and lung volume [5].

Thoracic pain is one of the common conditions found in all of the societies and nowadays its prevalence is increasing following a decrease in mobility, an increase in weight of the trunk, inappropriate positioning of the spine during daily activities, and increasing use of computers [6]. Physical activities, extensor exercises, and constant control of kyphosis by orthopedic surgeons are the examples of related treatments [7]. If kyphosis is progressive, a brace needs to be applied [8]. In that case, ongoing assessment of kyphosis is essential to control the thoracic curve and to evaluate the outcomes of the treatment.

Lumbar lordosis is the ventral curvature of the spine formed by wedging of the lumbar vertebrae and intervertebral discs [9]. Several studies have indicated the clinical and functional importance of lumbar lordosis [10]. Lumbar lordosis is a key component in maintaining the sagittal balance. According to some studies as lordosis increases, thoracic kyphosis also increases; however, some studies have indicated that an increase in lordosis is accompanied by a decrease in kyphosis [11,12]. The abnormal lumbar curvature can lead to imbalance in the standing position [2].

Medical examinations have shown that lumbar pain rarely has pathophysiological causes [13]. Pain intensifies at night following muscular weakness and in the morning and decreases after daily activities [14].

Assessment of kyphosis is usually performed via lateral radiography of the spine imposed on an X-ray [15]. Continuous radiography is expensive and also potentially life-threatening [16]; hence, researchers have attempted to perform this assessment via non-invasive techniques [15].

The use of a flexible ruler as a means of non-invasive measurement of kyphosis and lordosis is cheap and accessible with a simple application [16]. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to evaluate the kyphosis and lordosis angles by using a flexible ruler and their relationship with pain severity and frequency in male and female students.

Materials and Methods

In this observational, cross-sectional, descriptive study, 241 (157 females and 84 males) students of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences were enrolled.

Sample size was calculated based on the number of newly entered students to the above mentioned university (650 female students, 350 male students) and the population ratio (p) of 68% from previous studies. The present study was ethically approved by the related committee of Hamadan University of medical sciences. All participants took part in the study with full awareness and voluntarily. Students who had experienced rheumatologic or neurological pain and orthopedic diseases such as idiopathic scoliosis and difference in leg length discrepancy were excluded [1]. A pain questionnaire was used to examine the severity and frequency of the lumbar and inter-scapular pain. Pain severity was assessed via a visual numerical scale from 0 to 10.

Pain frequency was measured as follows: never or rarely (perceived pain, once a month or less), sometimes (perceived pain, twice or three times a month), and often (perceived pain, once to three times a week or more) [1].

A flexible ruler was used to examine the thoracic and lumbar curvature. Validity and reliability studies for the flexible ruler and non-radiographic method have been performed previously [17].

The amount of lordosis and kyphosis was measured three times by a single examiner using a flexible ruler and the average value was reported. Also, the inter-observer correlation coefficient was 0.87 with a measurement error of 0.006.

To assess the curvatures by using a flexible ruler, participants were asked to stand in the normal anatomical position with the examiner standing at the back. First lumbar (L1) and second sacral (S2) vertebrae were considered as markers for evaluating the lumbar curvature. In order to identify S2, the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) was marked. The midpoint between the two PSISs, according to Gray's Anatomy, was considered as the spinous process of the S2.

To identify L1, the examiner pressed the lower back above the iliac crest in order to move the soft tissue laterally where the two thumbs reach horizontally together on the L4 spinous process. By counting up the vertebrae, the L1 spinous process was identified. Then, the flexible ruler was placed on L1 and S2 while a hand pressed on it to eliminate the gap between the ruler and the skin. The ruler was put on a sheet and the lumbar curve was drawn afterwards [18].

Measurement of the thoracic curvature was performed in a similar manner to that of the lumbar curvature. The only difference was that C7 and the junction of T12 and L1 were marked in order to measure the thoracic curvature [19]. The thoracic curve was drawn by using a flexible ruler. Two ends of the curve reached together, and a L line was drawn whose midline vertically reached the middle of the curve through the h line. The lengths of h and L lines were calculated and the aforementioned angle was obtained. The line was drawn from the side of the ruler which touched the skin.

| θ=4 arc tan 2 h/L |

Using descriptive statistics, mean values of kyphotic and lordotic angles and their prevalence based on gender were reported.

Because of the misfit of the data to normal hypothesis, non-parametric tests such as the Mann-Whitney U test and non-parametric correlation tests of Gamma and Kendall were applied. Data processing was carried out via SPSS ver. 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

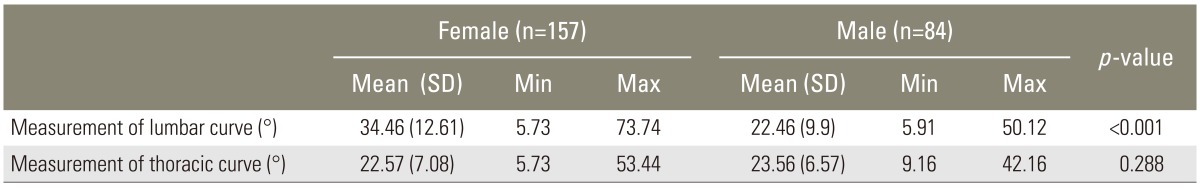

Mean values of lordotic and kyphotic angles are shown in Table 1. Mean value of the lumbar arch was 34.46°±12.61° and 22.46°±9.9° in female students and male students, respectively. Lumbar lordosis showed a significant difference between the two student groups (p<0.001), while there was no difference in the thoracic curvature (p=0.288) (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of the mean of lordotic and kyphotic angles in females and males.

SD, standard deviation; Min, minimum; Max, maximum.

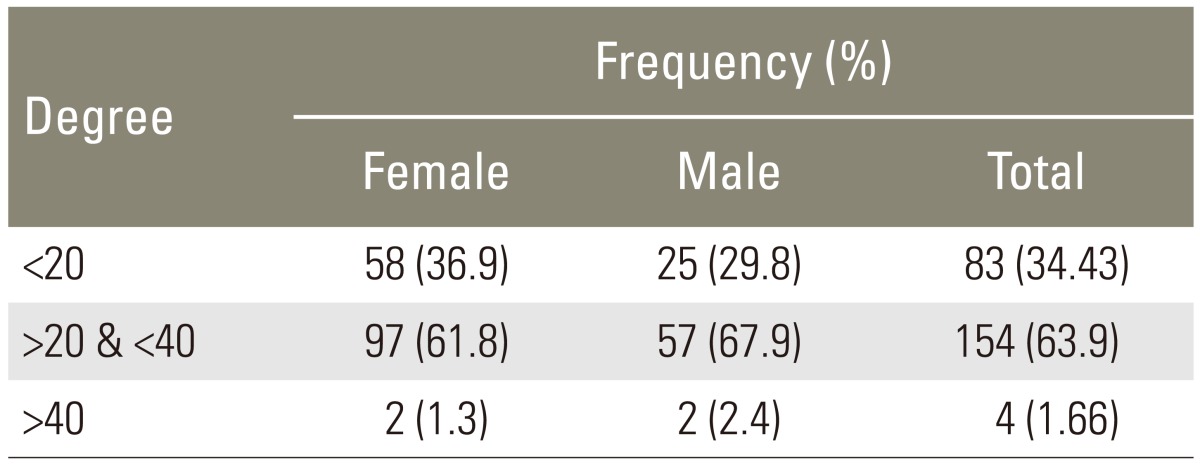

Table 2 indicates the prevalence of kyphosis according to gender and angles of <20, >20 & <40, and >40. In brief, 36.9% and 67.9% kyphotic angles of <20, 16.8% and 67.9% kyphotic angles of >20 & <40, and 1.3% and 2.4% kyphotic angles of >40, were identified in female students and male students, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of the kyphosis according to the gender (°).

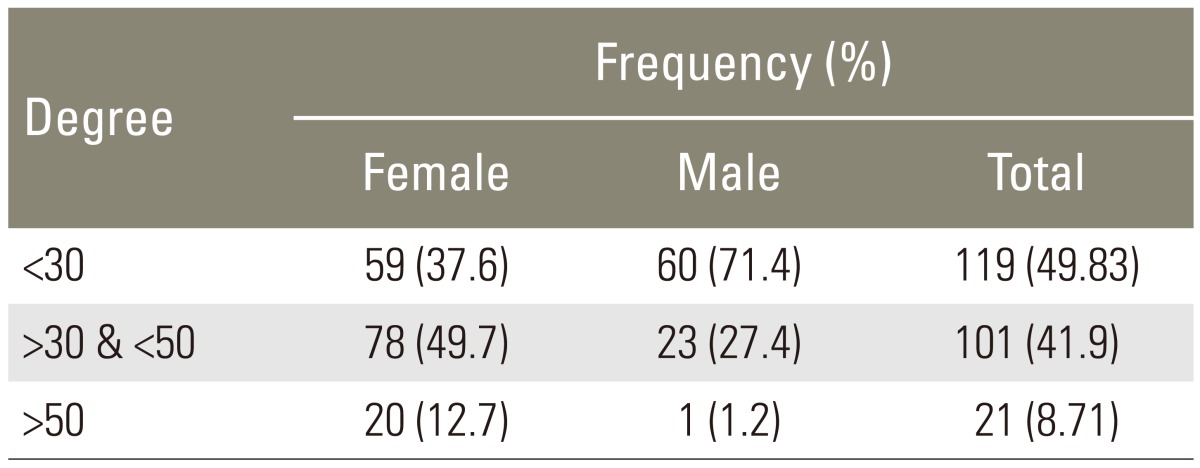

Prevalence of lordosis based on gender and angles classified as <30, >30 & <50, and >50 is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Prevalence of the lordosis according to the gender (°).

In brief, 37.6% and 71.4 % <30 lordosis, 49.7% and 27.4% >30 & <50 lordosis, and 12.7% and 1.2% >50 lordosis, were found in female students and male students, respectively (Table 3).

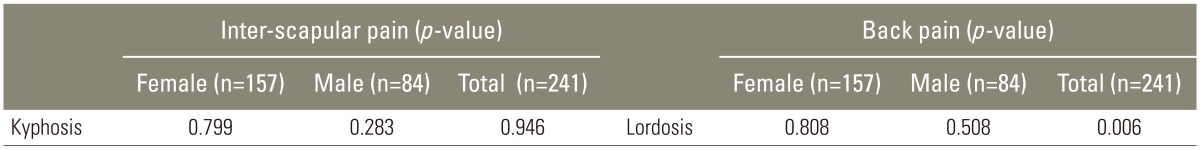

Table 4 indicates the relationship between kyphosis and interscapular pain severity in male students, female students, and both, as well as the relationship between lordosis and lumbar pain severity.

Table 4. Results of Kendall correlation test for investigating the relationship of kyphasis and lordosis with lumbar and inter-scapular pain in the whole sample.

No significant relationship was observed between kyphosis measured by using a flexible ruler and inter-scapular pain in both student groups (p=0.946), whereas the relationship between lordosis and lumbar pain severity in the whole study sample was significant (p=0.006).

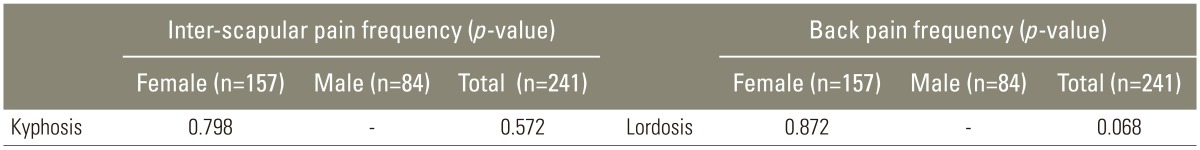

There was no relationship between kyphosis and inter-scapular pain frequency in male students and female students and also in the whole study sample (p=0.068) (Table 5).

Table 5. Results of the Kendall correlation test for investigating the relationship of kyphosis and lordosis with frequency of the lumber and inter-scapular pain in the whole sample.

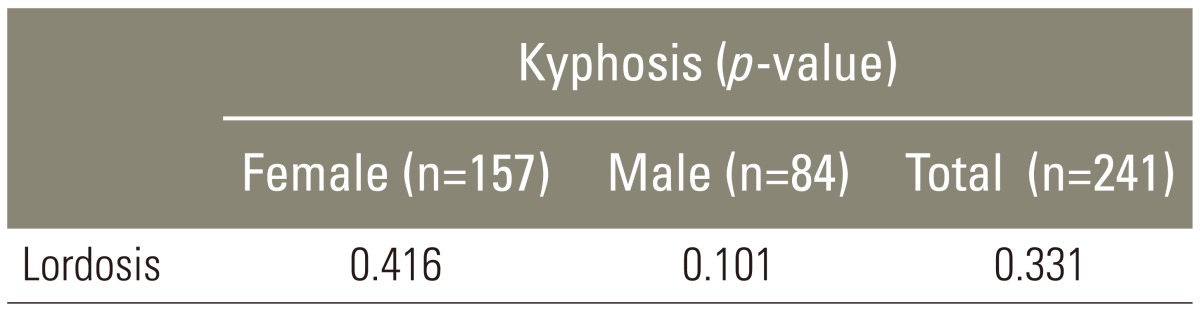

No significant relationship was found between kyphosis and lordosis in the whole study sample based on gender (p=0.331, Table 6).

Table 6. Results of the Kendall correlation test for investigating the relationship of kyphosis and lordosis.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to investigate the prevalence of kyphosis and lordosis by using a flexible ruler and also of musculoskeletal pain and their relationship with pain severity and frequency in male and female students of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

According to the results, the mean values of lordosis and kyphosis were 34.46°±12.61° and 22.57°±7.08° in female students and 22.46°±9.9° and 23.56°±6.57° in male students, respectively.

Many studies have proved the validity and reliability of using flexicurve in comparison with radiographic data. A systematic review of validity and reliability of the non-radiographic method showed high to very high levels of reliability of the Flexicurve. This study suggested that flexicurve is an easy to use, hand-held tool, and it could replace radiography in evaluating lumbar lordosis [17]. However, with respect to cervical lordosis, there are some studies that showed that the flexicurve sagittal skin contour measurement has poor concurrent validity compared to radiographic measurements [20]. It seems that postural or X-ray positioning and radiographic analysis lead to appearance of confounding variables, which affects the results. Also, obesity, muscular development, previous trauma, and biomechanical complexities of the cervical spine could result in some differences in the measurement of surface contour compared to lateral radiographs [20]. According to previous research, the flexicurve kyphosis angle provides strong validity and reliability. Furthermore, it is inexpensive and can be easily used by the entry-level research staff, requires short measurement time, and does not expose the patients to high radiation risk. It seems that the use of this measurement method for detection of spine abnormalities and examination of the posture in healthy subjects is quite beneficial [21].

On the other hand, postural age-related changes include a forward head, rounded shoulders, increased thoracic kyphosis, decreased lumbar lordosis, and flexed hips and knees [22]. With age, a progressive change occurs in the kyphotic angle in both genders [23]. However, there are limited evidences to illustrate the causes of age-related lumbar lordosis, and further research is required to determine the influence of age on lordosis [22]. Therefore, in the present study, as all participants were young (aged between 19 to 21 years), we did not aim to evaluate the effect of age on the amount of kyphosis and lordosis.

Lumbar lordosis showed a significant difference between both genders (p<0.001); however, no difference was seen in the thoracic curve (p=0.288). In other words, the mean value of lordosis was higher in female students than in male students. The mean value of kyphosis was higher in male students than in female students, although this difference was not significant.

Altogether, the lumbar curve was greater in female students compared to male students in this study. Although some studies showed that lumbar lordosis is not different between females and males [24], results of the present study support the finding that lumbar curve is greater in females than in males [22].

The prevalence of abnormal kyphosis was 2.4% and 1.2% in male students and female students, respectively. Therefore, abnormal kyphosis was more common in male students compared with female students. Abnormal lordosis was more common in female students than in male students (12.7% in female students and 1.2% in male students).The prevalence of kyphosis and lordosis beyond the normal range in students of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences was 1.66% and 8.71%, respectively.

There was no significant relationship between kyphosis and inter-scapular pain in male students and female students and the whole study sample; while, they were significantly related in the study by Griegel-Morris et al. [1]. This difference in the result was most likely due to the different methods of measurement. In the present study, kyphosis was measured by using a flexible ruler which is more valid and subtle than observational assessment which could consider kyphosis of 20°-40° as an abnormality.

A significant relationship was observed between lumbar pain and lordosis in the whole study sample, although it was not significant according to gender. Therefore, it could be said that gender had no effect on the relationship between pain and severity of the abnormalities, which was probably due to the homogeneity of male and female students with respect to abnormality and pain. Several factors are involved in causing low back pain such as disc degeneration, muscle stretch, age, and occupation [25]. Clinical observations indicate the role of postural anomalies in low back pain [13]. In this study, lordosis in the students was significantly related to low back pain, and this finding corresponded with that in the study by McKenzie [26] which showed that low back pain occurred as a result of long and inaccurate over-stretching of the soft tissue in an abnormal posture. That is, as the extensor muscles become overloaded during lordosis, low back pain may emerge.

There was no significant relationship between the abnormality and pain frequency, which corresponded with the results of the study carried out in younger and older adults [1].

Since cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spinal regions are biomechanically related, any change in each arch might be due to the postural alteration in other arches [27]. In the present study, the relationship between lordosis and kyphosis was not significant. Perhaps, increasing the sample size could help in demonstrating a significant relationship between lordosis and kyphosis.

Conclusions

According to the results, lordosis may play a key role in low back pain, which might result from muscular imbalance and overstretching of the muscles and ligaments. Low back pain may also be caused by psychological factors, which usually cannot be controlled by the researcher in most studies. It could be concluded that through a simple examination of the spine, such abnormalities can be identified as well as chronic spinal pain can be prevented.

Findings of this study indicate the importance of postural evaluation in youth, in which chronic pain is rarely related to other diseases, and hence, the pain could be considered to occur as a result of inappropriate posture and can be managed by performing corrective exercises.

Involvement of a team of professionals in occupational therapy, physical therapy, ergonomics, and orthopedic surgery is recommended in order to provide information to individuals about the anatomy and biomechanics of the spine, risk factors that contribute to abnormalities, accurate positions for sitting, standing, lying, carrying objects, and using instruments, and performing exercises to strengthen the weak muscles and correct the abnormal posture, known as back school program for musculoskeletal pain.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Griegel-Morris P, Larson K, Mueller-Klaus K, Oatis CA. Incidence of common postural abnormalities in the cervical, shoulder, and thoracic regions and their association with pain in two age groups of healthy subjects. Phys Ther. 1992;72:425–431. doi: 10.1093/ptj/72.6.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG, Rodgers MM, Romani WA. Muscles: testing and function with posture and pain. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nitzschke E, Hildenbrand M. Epidemiology of kyphosis in school children. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1990;128:477–481. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1039600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afshari F, Salari F. Prevalence of vertebral deformities among high school students in Tehran. Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herring JA, Tachdjian MO Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children. Tachdjian's pediatric orthopaedics: from the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liebenson C. Rehabilitation of the spine: a practitioner's manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise foundations and techniques foundations. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moe JH, Lonstein JE. Moe's textbook of scoliosis and other spinal deformities. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaz G, Roussouly P, Berthonnaud E, Dimnet J. Sagittal morphology and equilibrium of pelvis and spine. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:80–87. doi: 10.1007/s005860000224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang JS, Lee SH, Min JH, Maeng DH. Influence of lumbar lordosis restoration on thoracic curve and sagittal position in lumbar degenerative kyphosis patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:280–284. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318191e792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roussouly P, Nnadi C. Sagittal plane deformity: an overview of interpretation and management. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1824–1836. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1476-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwab F, Patel A, Ungar B, Farcy JP, Lafage V. Adult spinal deformity-postoperative standing imbalance: how much can you tolerate? An overview of key parameters in assessing alignment and planning corrective surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:2224–2231. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ee6bd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.During J, Goudfrooij H, Keessen W, Beeker TW, Crowe A. Toward standards for posture. Postural characteristics of the lower back system in normal and pathologic conditions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1985;10:83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franklin ME, Conner-Kerr T. An analysis of posture and back pain in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28:133–138. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.3.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leroux MA, Zabjek K, Simard G, Badeaux J, Coillard C, Rivard CH. A noninvasive anthropometric technique for measuring kyphosis and lordosis: an application for idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:1689–1694. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lovell FW, Rothstein JM, Personius WJ. Reliability of clinical measurements of lumbar lordosis taken with a flexible rule. Phys Ther. 1989;69:96–105. doi: 10.1093/ptj/69.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrett E, McCreesh K, Lewis J. Reliability and validity of non-radiographic methods of thoracic kyphosis measurement: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2014;19:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magee DJ. Orthopedic physical assessment. Princeton: Recording for the Blind & Dyslexic; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Post RB, Leferink VJ. Spinal mobility: sagittal range of motion measured with the SpinalMouse, a new non-invasive device. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:187–192. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0641-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison DE, Haas JW, Cailliet R, Harrison DD, Holland B, Janik TJ. Concurrent validity of flexicurve instrument measurements: sagittal skin contour of the cervical spine compared with lateral cervical radiographic measurements. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:597–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinman MR. Comparison of thoracic kyphosis and postural stiffness in younger and older women. Spine J. 2004;4:413–417. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Been E, Kalichman L. Lumbar lordosis. Spine J. 2014;14:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.07.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyle JJ, Milne N, Singer KP. Influence of age on cervicothoracic spinal curvature: an ex vivo radiographic survey. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2002;17:361–367. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(02)00030-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson RP, McManus AC. Radiographic analysis of sagittal plane alignment and balance in standing volunteers and patients with low back pain matched for age, sex, and size: a prospective controlled clinical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:1611–1618. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199407001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christie HJ, Kumar S, Warren SA. Postural aberrations in low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:218–224. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKenzie R. The cervical and thoracic spine: mechanical diagnosis and therapy. Waikanae: Spinal Publications (N.Z.) Ltd; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau KT, Cheung KY, Chan KB, Chan MH, Lo KY, Chiu TT. Relationships between sagittal postures of thoracic and cervical spine, presence of neck pain, neck pain severity and disability. Man Ther. 2010;15:457–462. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]