Key Points

CMV reactivation fundamentally resets posttransplant CD8 reconstitution, resulting in massive expansion of CMV-specific CD8 Tem.

CMV reactivation is associated with defects in the underlying TCRβ immune repertoire.

Abstract

Although cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation has long been implicated in posttransplant immune dysfunction, the molecular mechanisms that drive this phenomenon remain undetermined. To address this, we combined multiparameter flow cytometric analysis and T-cell subpopulation sorting with high-throughput sequencing of the T-cell repertoire, to produce a thorough evaluation of the impact of CMV reactivation on T-cell reconstitution after unrelated-donor hematopoietic stem cell transplant. We observed that CMV reactivation drove a >50-fold specific expansion of Granzyme Bhigh/CD28low/CD57high/CD8+ effector memory T cells (Tem) and resulted in a linked contraction of all naive T cells, including CD31+/CD4+ putative thymic emigrants. T-cell receptor β (TCRβ) deep sequencing revealed a striking contraction of CD8+ Tem diversity due to CMV-specific clonal expansions in reactivating patients. In addition to querying the topography of the expanding CMV-specific T-cell clones, deep sequencing allowed us, for the first time, to exhaustively evaluate the underlying TCR repertoire. Our results reveal new evidence for significant defects in the underlying CD8 Tem TCR repertoire in patients who reactivate CMV, providing the first molecular evidence that, in addition to driving expansion of virus-specific cells, CMV reactivation has a detrimental impact on the integrity and heterogeneity of the rest of the T-cell repertoire. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT01012492.

Introduction

One of the major obstacles associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) is the fact that this treatment, although curative for many diseases, is associated with significant toxicity and resultant transplant-related mortality (TRM).1-4 TRM takes on many forms, but is often related to dysfunctional immune reconstitution after HSCT. The extent to which cytomegalovirus (CMV) influences posttransplant immune dysfunction has been the subject of intense interest,1,5-9 with several studies documenting the increased risk of TRM based on CMV serostatus, infection, and expansion of CMV-tetramer–positive cells.10-22 However, although the phenomenology of CMV’s impact on TRM is well documented, the causative molecular immunologic mechanisms remain unknown. To address these questions, we have undertaken a detailed assessment of immunologic reconstitution after HSCT using new deep-sequencing technologies that have allowed us to investigate this issue at a level of molecular detail not previously possible. We present evidence that, in a cohort of patients undergoing unrelated-donor transplantation, CMV reactivation is capable of resetting CD8 T-cell homeostasis, resulting in the clonal expansion of CMV-specific CD8 effector memory T cells (Tem). Importantly, T-cell receptor β (TCRβ) deep-sequencing analysis allowed us, for the first time, to look beyond the clonal expansions, and to evaluate the remainder of the TCR repertoire and, thereby, to assess the impact of CMV reactivation on the integrity of the repertoire as a whole. This analysis has revealed that CMV reactivation was associated with the development of defects in the underlying Tem TCR repertoire, providing the strongest molecular evidence to date linking CMV reactivation and quantitative immune dysregulation after HSCT.

Methods

Study design

Seventeen patients underwent prospective, calendar-based clinical and immune monitoring after enrollment on 2 contemporaneous clinical trials: (1) The Bone Marrow Immune Monitoring Protocol and (2) The Abatacept Feasibility Study. Both studies were institutional review board–approved and conducted between 2010 and 2013, as previously described.23 Patient and transplant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients were analyzed prospectively for CMV reactivation by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and those that reactivated CMV (>300 copies per mL whole blood) were treated with antiviral therapy according to institutional standards. All patients reactivating CMV developed viremia that was responsive to either valganciclovir or ganciclovir. No patient developed CMV disease. In addition to patient analyses, 10 healthy adult controls also underwent single time-point immune analysis and 7 healthy adult controls underwent TCRβ repertoire analysis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and clinical outcomes

| UPN | Recip. age, y | Donor age, y | Sex, M/F | Disease, status | HLA typing | Prep. reg. | GVHD prop. reg. | Graft source | CMV status, D/R | CMV react., Y/N | Grade II-IV aGVHD to day +100, Y/N (day) | Grade III-IV aGVHD to day +100, Y/N (day) | Late aGVHD (day) | Systemic aGVHD Tx | Mild cGVHD, Y/N | Mod/ Sev cGVHD, Y/N | Systemic cGVHD Tx through day 365 | Non-CMV infections | Relapse Y/N, day post-Tx | Alive day 365 post-Tx, Y/N (day of death) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001-001 | 46 | 24 | M | AML, CR2 | A: 01/03; B: 08/52 | Cw: 1202*/0701; DRB1: 0301/0404* Recip. Cw: 1216 | Bu/ Cy | CNI/ MTX/ AB | PBSC | +/+ | Y | N | N | Y (220) | Steroids | N | N | N | Bacteremia | N | Y |

| 001-002 | 61 | 20 | F | AML, CR1 | A: 02/68; B: 18*/27* Recip. B: 08 | Cw: 0701/0704; DRB1: 1104/1501 | Flu/ Mel | CNI/ MTX/ AB | PBSC | −/− | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Short-course steroids | None | N | Y |

| 001-004 | 74 | 33 | F | AML, CR2 | A: 03/68; B: 07/18 | Cw: 0701*/0702; DRB1: 1401/1501* Recip. Cw: 0501 | Flu/ Mel | CNI/ MTX/ AB | PBSC | −/+ | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Bacteremia, parainflu. | Y, day +98 | N (121) |

| 001-005 | 59 | 19 | F | MDS → AML | A: 01/29; B: 08/44 | Cw: 0701/1601; DRB1: 0301/0701 | Flu/ Mel | CNI/ MTX/ AB | PBSC | −/− | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Steroids, siro. | Rhinovirus | N | Y |

| 001-006 | 43 | 21 | M | Biphen. Ph+ leukemia, CR1 | A: 03/11; B: 07/35 | Cw: 0401/0702; DRB1: 0101/1501 | TBI/ Cy | CNI/ MTX/ AB | PBSC | −/+ | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Steroids, cyclo. | None | N | Y |

| 001-007 | 46 | 45 | M | ALL, CR1 | A: 01/24*; B: 08/18* Recip. A: 26 | Cw: 0701/1203; DRB1: 0701/1104 | TBI/ Cy | CNI/ MTX/ AB | PBSC | +/+ | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | None | Y, day +121 | N (147) |

| 001-008 | 39 | 36 | M | AML, CR1 | A: 24/32; B: 27/40 | C: 0102/0202; DRB1: 0101/1601 | Bu/ Cy | CNI/ MTX/ AB | PBSC | +/+ | Y | Y (84) | Y | N | Steroids | N | Y | Steroids, ritux. | None | N | Y |

| 001-009 | 40 | 27 | M | CML, EMD | A: 02/24*; B: 14/45* Recip. A: 68 | Cw: 0802/1601; DRB1: 1001/1303 | Bu/ Cy | CNI/ MTX/ AB | PBSC | −/+ | Y | N, did develop grade I skin (49) | N | N | Steroids | N | Y | Steroids, cyclo., MMF | None | N | Y |

| 002-001 | 22 | 27 | F | ALL, CR3 | A: 02/68; B: 40/51 | Cw: 0304/1402; DRB1: 0401/1101 | TBI/ Cy | CNI/ MTX/ AB | BM | +/+ | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | None | N | Y |

| 002-002 | 17 | 30 | F | ALL, IF | A: 02/03; B: 07/39 | Cw: 0701/0702; DRB1: 1401*/1303* Recip. DRB1: 1001 | TBI/ Cy | CNI/ MTX/ AB | BM | −/+ | Y | Y (29) | N | N | Steroids | N | Y | Steroids, cyclo. | Cellulitis, BK virus, LPD | N | Y |

| 003-001 | 30 | 40 | M | ALL, PIF | A: 02/02; B: 07/49 | Cw: 0701/0702; DRB1: 0401/0405 | Bu/ Cy | CNI/ MTX | PBSC | −/+ | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y, day +562 | Y |

| 003-002 | 35 | 45 | F | MF | A: 23/30*; B: 07/78* Recip. A: 33 | Cw: 0702/1601; DRB1: 0701/0901 | Bu/ Cy | CNI/ MTX | PBSC | +/− | Y | Y (48) | N | N | Steroids | N | Y | Steroids, tacro. | N | N | Y |

| 003-003 | 66 | 19 | M | MDS | A: 02; B: 15/44 | Cw: 0304/0501; DRB1: 0401 | Flu/ Mel | CNI/ MTX | PBSC | +/+ | N | Y (35) | Y (35) | N | Steroids inflix. | N | N | N | Y | N | Y |

| 003-004 | 48 | 25 | F | CP CML, TKI R/I | A: 01/29; B: 08/44 | Cw: 0501*/0701; DRB1: 0301/1201* Recip. Cw: 0102 | Bu/ Cy | CNI/ MTX | PBSC | +/− | N | Y (11) | Y (11) | N/A | Steroids inflix. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N | N (46) |

| 003-005 | 64 | 19 | F | ALL, CR2 | A: 02; B: 07/18 | Cw: 0501/0702; DRB1: 0301/1501 | TBI/ Cy | CNI/ MTX | PBSC | +/− | Y | N | N | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N | N (80) |

| 003-006 | 41 | 55 | M | MDS | A: 02/03; B: 44*/40* Recip. B: 39 | Cw: 0304/0501; DRB1: 0403/1302 | Bu/ Cy/ ATG | CNI/ MTX | PBSC | +/− | N | Y (44) | Y (44) | N | Steroids inflix. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N | N (95) |

| 004-001 | 12 | 29 | M | ALL, CR1 | A: 02/11; B: 15/44 | Cw: 0304/1601; DRB1: 0401/0701 | TBI/ Cy/ VP16 | CNI/ MTX | BM | −/+ | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y |

AB, abatacept; aGVHD, acute GVHD; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; Biphen., biphenotypic; BM, bone marrow; Bu, busulfan; cGVHD, chronic GVHD; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; CP, chronic phase; CR, complete remission; Cy, cyclophosphamide; cyclo., cyclosporine; D/R, donor/recipient; EMD, extramedullary disease; F, female; Flu, fludarabine; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; IF, induction failure; inflix., infliximab; LPD, lymphoproliferative disease; M, male; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; Mel, melphalan; MF, myelofibrosis; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; Mod/Sev, moderate/severe; MTX, methotrexate; N, no; N/A, not applicable; parainflu., parainfluenza; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome positive; PIF, primary induction failure; Prep. reg., preparative regimen; prop. reg., prophylaxis regimen; react., reactivation; Recip., recipient; R/I, resistant/intolerant; ritux., rituximab; siro., sirolimus; tacro., tacrolimus; TBI, total body irradiation; TKI, receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor; Tx, treatment; UPN, unidentified patient number; VP16, etoposide; Y, yes.

Human studies ethics statement

The patients and controls described in this manuscript were enrolled in clinical trials that were conducted according to the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki, and which were approved by the institutional review boards. Written informed consent was received from all participants.

Immunologic analysis

Patients underwent longitudinal multiparameter flow cytometric analysis of immune reconstitution, CMV functional response, tetramer analysis, and flow cytometric sorting of CD8+ naive T cells (Tnaive), Tem, and Tetramer+ cells as described in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site) and supplemental Tables 1-2.

TCRβ receptor diversity analysis by deep sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted and quantified (Qiagen) from unsorted peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and from sorted CD8+ Tnaive, Tem, and CMV-tetramer+ cells; TCRβ chain sequencing was performed at Adaptive Biotechnologies using the ImmunoSEQ platform24-26 with primers specific for all 54 known expressed Vβ regions and all 13 Jβ regions. TCRβ deep-sequencing depth was sufficient to achieve at least fivefold coverage of every original template, sufficient to prevent sampling effects.25 An average of 3.3 × 106 ± 3.4 × 105 reads were generated for the PBMC, Tnaive, and Tem samples (supplemental Table 3).

Bioinformatic analysis was performed on the sequencing data using the ImmunoSEQ platform, which included a determination of: the number and sequence of each of the productive unique Vβ and Jβ genes identified within each sample, the degree of clone sharing between samples, and the identity of the shared clones. In addition, clonality and TCRβ repertoire hole analysis was performed as described in detail in the supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

To identify predictors of high CD8+ Tem status, 2 statistical tests were used: for binary variables, we calculated the nonparametric Kendall τ-b statistic using the cor.test function in R (http://www.R-project.org/). For the 2 continuous variables (recipient age and donor age), we carried out Spearman rank correlation, also using R. Additional statistical analyses were calculated with the Mann-Whitney t test with 95% confidence intervals, using GraphPad Inc software, Prism version 5.0.

Results

Patient characteristics and statistical analysis

This study was based upon prospective, calendar-based clinical and immune monitoring of HSCT recipients enrolled on 2 contemporaneous clinical trials (Table 1). All patients received myeloablative pretransplant conditioning and unmanipulated unrelated-donor allografts.23 Immune reconstitution was monitored in detail in all patients on-study, and revealed an extremely wide variability in the pace and character of their immune reconstitution, for which the heterogeneity was most prominent in the CD8+ Tem compartment, with over 200-fold variability in the first year posttransplant (Figure 1A). To determine the factors that were contributing to this variability, we performed univariate analysis of the following patient characteristics and posttransplant complications (Table 2): patient sex, age, donor age, degree of donor/recipient HLA matching, relapse, posttransplant GVHD prophylaxis regimen (cyclosporine/methotrexate vs cyclosporine/methotrexate/abatacept),23 grade II-IV aGVHD, moderate-severe cGVHD, infections (including respiratory viruses and bacterial infections), and CMV reactivation. Univariate analysis with the Kendall τ-b test (for binary variables) or with the Spearman rank test (for continuous variables) was used to determine which variables were positively correlated with elevated CD8+ Tem counts. This analysis identified only CMV reactivation as predictive of day +365 CD8+ Tem count (P = .009 for CMV reactivation, P = not significant for all other parameters, Table 2). Of note, none of the clinical variables listed in Table 2 were predictive of total CD3+, CD4+, or CD8+ T-cell counts (not shown). Although this study was not sufficiently large to build a full multivariate model, we did perform partial least squares (PLS) discriminant analysis to determine the primary predictors of high CD8 Tem counts,27 and this analysis also identified CMV reactivation as the primary driver of CD8 Tem expansion (not shown).

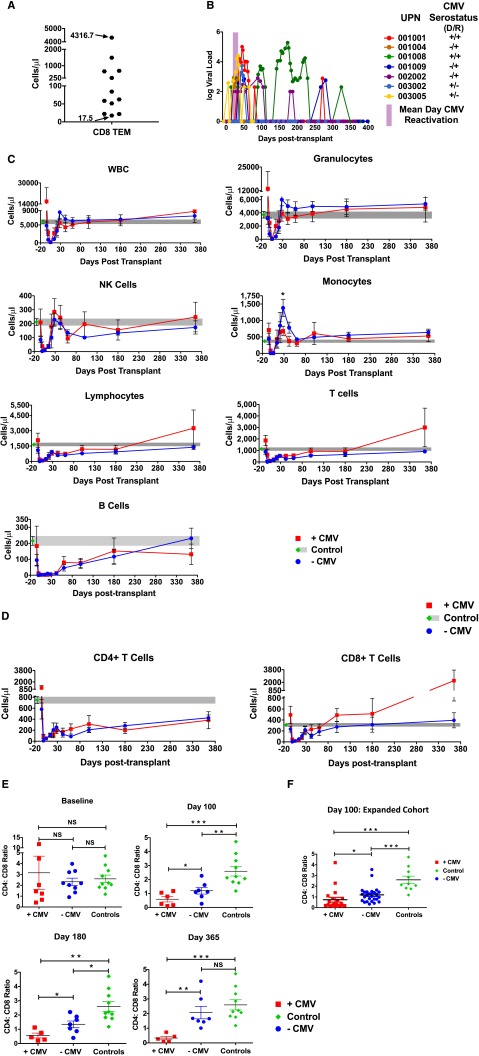

Figure 1.

Viral reactivation and T-cell reconstitution in CMV-reactivating and nonreactivating patients. (A) CD8+ Tem counts at day +365 posttransplant. (B) CMV viral load measured longitudinally. Each CMV-reactivating patient is shown as a unique colored line. Donor/recipient (D/R) pretransplant CMV serostatus is also indicated. Also shown is the mean day of CMV reactivation (±standard error of the mean [SEM]), depicted as a purple bar. (C) Longitudinal analysis of WBC, granulocytes, NK cells, monocytes, lymphocytes, total T cells, and total B cells posttransplant. Data are mean ± SEM in +CMV patients (red traces, n = 7), −CMV patients (blue traces, n = 10), and healthy controls (green diamond longitudinally extended as gray area, n = 10). *P ≤ .05; Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (D) Longitudinal analysis of absolute numbers ± SEM of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell reconstitution (+CMV [n = 7] and −CMV [n = 10]). Also shown are the means ± SEM of 10 healthy controls (green diamond extended longitudinally as gray area). (E) Analysis of CD4:CD8 ratio at baseline and days 100, 180, and 365 posttransplant as mean ± SEM in +CMV, −CMV, and healthy controls (green diamond). *P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01; ***P ≤ .001; NS, nonsignificant, Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (F) Analysis of CD4:CD8 ratio at day 100 of an extended cohort of 46 HSCT patients: +CMV (n = 26) and −CMV (n = 20).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of contributors to day +365 CD8+ Tem counts

| Possible contributors to the day 365 CD8 Tem count | P value |

|---|---|

| CMV reactivation (Y/N) | .009 |

| Sex (M/F) | .24 |

| Moderate/severe cGVHD (Y/N) | .82 |

| Grade II-IV aGVHD to day +100 (Y/N) | .87 |

| Relapse (Y/N) | .92 |

| Posttransplant immunosuppression + abatacept (Y/N) | .87 |

| Non-CMV infections (Y/N) | .43 |

| Recipient age | .89 |

| Donor age | .1 |

| 8/8 vs 7/8 HLA match | .19 |

CMV reactivation kinetics

Figure 1B shows the kinetics of CMV reactivation in the +CMV cohort. The remaining patients (−CMV) did not demonstrate any CMV reactivation during the 1-year period of follow-up. As shown in the figure (purple bar), the mean day of first CMV reactivation in the +CMV cohort was 28 ± 4 days.

CMV reactivation resets CD8 Tem homeostasis

Although CMV reactivation did not impact the reconstitution kinetics of total white blood cells (WBCs), granulocytes, monocytes, total natural killer (NK) cells, lymphocytes, total T cells, B cells (Figure 1C), or total CD4+ T cells (Figure 1D), CMV reactivation was associated with significant expansion of CD8+ T cells, with a total CD8+ T-cell count at 1 year posttransplant that was more than fivefold higher in the +CMV compared with –CMV cohort (Figure 1D). Indeed, as shown in Figure 1E, the canonical inversion of the CD4:CD8 ratio occurred exclusively in CMV reactivating patients, with an increasingly inverted ratio observed in the +CMV cohort throughout the first year posttransplant, whereas –CMV patients progressively normalized this ratio. The inversion of the CD4:CD8 ratio in CMV-reactivating patients was validated in a larger cohort of 46 patients who underwent unrelated donor HSCT at Emory University and who received CD4 and CD8 T-cell counts at day +100 as a part of their clinical care (Figure 1F).

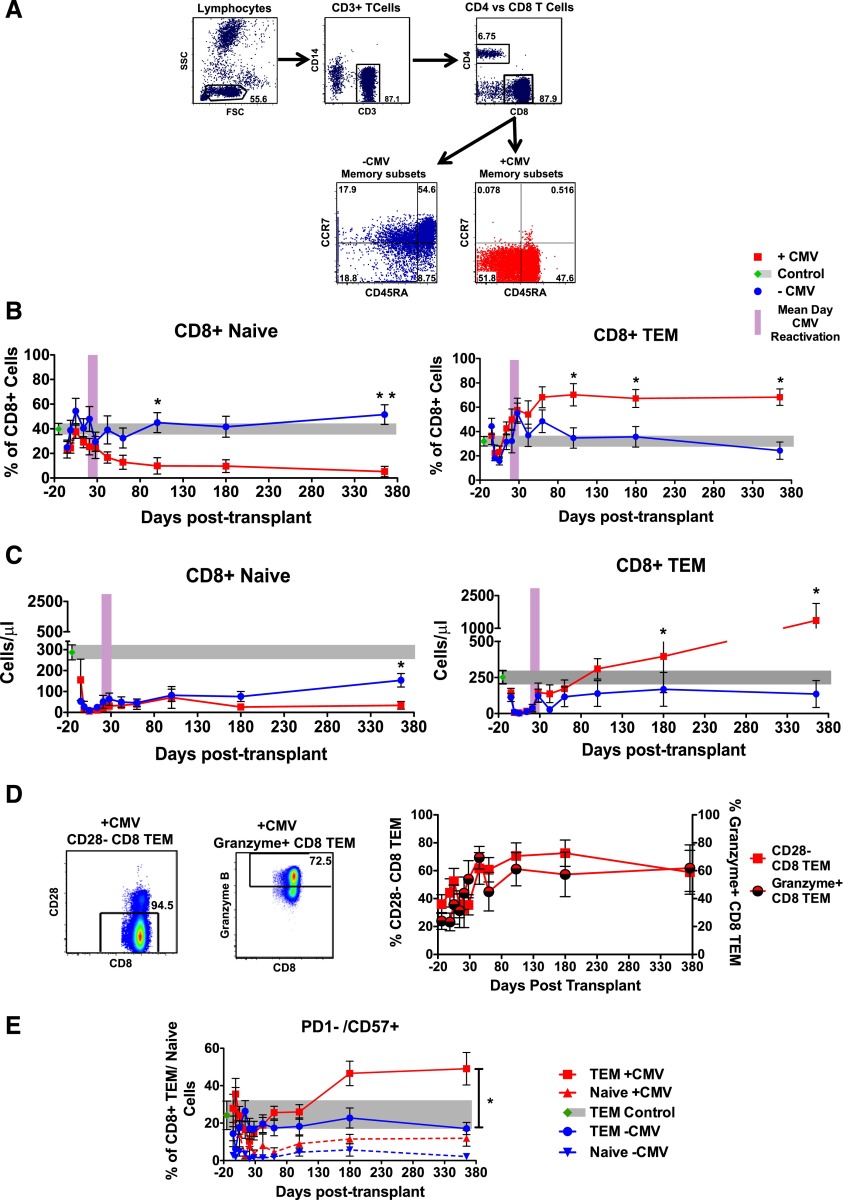

Figure 2A-C demonstrates that the reconstitution of total CD8+ T cells in the +CMV cohort was driven by a massive expansion of CD8+ Tem and, unexpectedly, with a contraction of CD8+ Tnaive. As shown in the figure, the reciprocal expansion/contraction of these 2 CD8 subpopulations occurred both in their relative proportions (Figure 2B) and in their absolute numbers (Figure 2C). This resulted in an average of >10-fold more CD8+ Tem in the +CMV cohort at day +365 compared with the −CMV cohort (P = .03) and fivefold fewer CD8+ Tnaive in the +CMV cohort at day +365 compared with the −CMV cohort (P = .02 at day +365). Importantly, as shown in Figure 2B, the inflection point of the CD8+ Tem expansion and the concomitant CD8+ Tnaive contraction closely correlated with the mean time to initial CMV reactivation (28 ± 4 days; purple bar). Indeed, as shown in this figure, the reconstitution of CD8 Tem was indistinguishable between the 2 cohorts prior to day +28, with the resetting of CD8 T-cell subpopulation homeostasis occurring in concert with the mean time to first CMV reactivation. The expanding CD8+ Tem in the +CMV cohort expressed many of the canonical markers of viral-reactive effector memory cells, including loss of CD28, gain of Granzyme B (Figure 2D), and expression of CD57 (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Longitudinal analysis of CD8 naive and memory T-cell subpopulation reconstitution in +CMV and −CMV patients. (A) Representative flow cytometry analysis of memory subset marker expression in CD8+ T cells. Cells were gated as follows: lymphocytes were identified by FSC and SSC, CD14−CD3+ T lymphocytes were identified, further distinguished into CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, and analyzed for their expression of CCR7 and CD45RA memory markers. Tnaive were identified as CCR7+/CD45RA+, TCM: CCR7+/CD45RA−, TEM: CCR7−/CD45RA−, TEMRA: CCR7−/CD45RA+. (B-C) Longitudinal analysis of CD8+ naive and Tem subsets depicted in percentage frequency (B) or absolute cell numbers (C). Data are mean ± SEM in +CMV patients (n = 7), −CMV patients (n = 10), and healthy controls (n = 10). Also shown is the mean day of CMV reactivation (±SEM), depicted as a purple bar. (D) Left, Representative flow cytometry analysis at day +365 shows CD28 expression (left panel) and Granzyme B expression (right panel) on CD8+ Tem. Right, Longitudinal analysis of mean ± SEM CD28−CD8+ Tem (left y-axis) and Granzyme B+CD8+ Tem (right y-axis). (E) Longitudinal analysis of PD-1−/CD57+CD8+ Tem (solid lines) and naive T cells (dotted lines) of +CMV (n = 7), −CMV (n = 10) patients, and healthy controls. All data are mean ± SEM. *P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01 Wilcoxon rank-sum test. CCR, C-C chemokine receptor; FSC, forward scatter; SSC, side scatter; TCM, central memory T cells; TEMRA, effector memory-RA T cells.

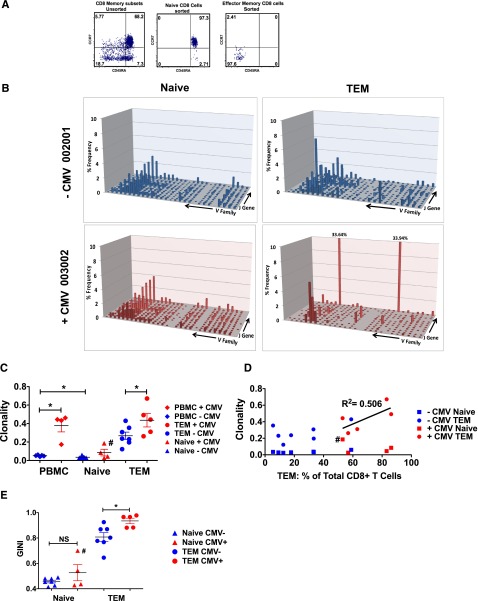

CMV reactivation drives antigen-specific T-cell clonal expansion

To determine whether the massive expansion of CD8 Tem in +CMV patients was due to viral reactivation, we first determined whether these T cells were derived from T-cell clonal expansions (TCEs).28,29 To accomplish this, we used TCRβ deep sequencing, and compared the clonality of T cells purified from +CMV and −CMV patients. Given the dichotomous effect that CMV reactivation had on the size of CD8+ T naive vs CD8+ Tem subpopulations (Figure 2B-C), it was critical to examine the TCR repertoire and clonality of purified naive and Tem subsets individually (Figure 3A), rather than determining the repertoire in unfractionated T cells, as has been previously performed.30-32 As shown in Figure 3, TCR deep-sequence analysis of the purified Tnaive and Tem samples enabled us to develop novel insights into the impact of CMV reactivation on posttransplant TCR repertoire dynamics. Thus, as shown in the representative TCR landscape (Figure 3B) and in Figure 3C-E, the clonality of the TCR repertoire of each sample was calculated using both normalized Shannon entropy number33 and Gini coefficients.34 This analysis confirmed that CMV reactivation was accompanied by a striking contraction of the TCR repertoire diversity in the CD8+ Tem population, which was directly linked to the global expansion of the Tem compartment: thus, as shown in Figure 3D, a linear relationship was observed between the CD8 Tem clonality and the percentage of Tem for the +CMV cohort. Taken together, these data provide strong evidence for TCEs in the +CMV cohort.

Figure 3.

Contraction of Tem TCR diversity but not Tnaive TCR diversity in CMV-reactivating patients. (A) Representative flow cytometry analysis illustrates the purity of CD8+ Tnaive and CD8+ Tem cells before (left plot) and after (middle and right plots) cell sorting. (B) Shown are representative graphs of the CD8+ naive (left column) and CD8+ Tem (right column) TCR landscape (showing frequencies of V and J gene combinations detected through deep sequencing) from 1 −CMV (blue) and 1 +CMV (red) patient. (C) Clonality of PBMC, CD8+ Tnaive, and CD8+ Tem are shown for −CMV and +CMV patients as measured by the inverse of the normalized Shannon entropy number. All data are mean ± SEM. *P ≤ .05; Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (D) The clonality of Tnaive and Tem CD8+ cells for each patient is compared with the percentage of Tem CD8+ cells detected via flow cytometry in each patient. Linear regression (R2 = 0.506) shows a correlation between expansion of Tem and increased Tem clonality in +CMV patients (red). No such relationship could be detected in −CMV patients (blue). (E) TCR diversity of CD8+ Tnaive and CD8+ Tem are shown for −CMV and +CMV patients as measured by the Gini coefficient.44 All data are mean ± SEM. *P ≤ .05; Wilcoxon rank-sum test. #Sorting purity of Tnaive from patient 001-008 could not be confirmed due to low yield.

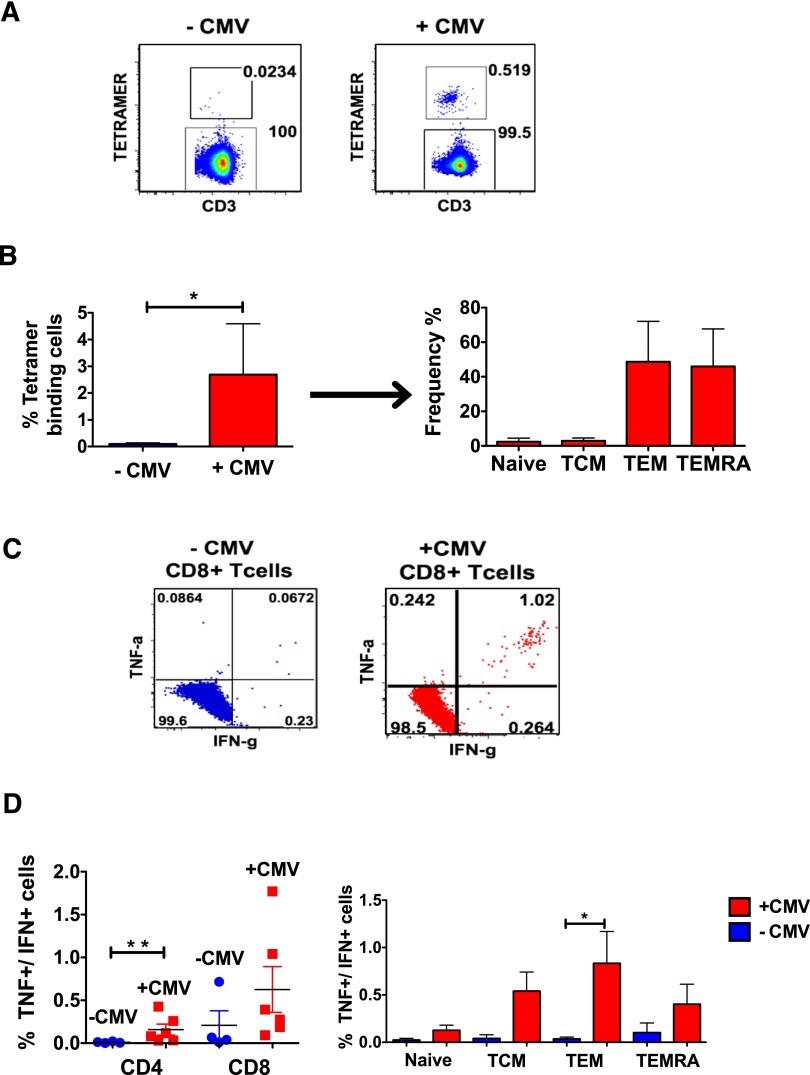

Having established that +CMV patients developed TCEs posttransplant, we then used 3 assays of increasing sensitivity to probe the degree to which CMV-specific T cells accounted for these TCEs: first, we enumerated CMV-tetramer+ cells in both the +CMV and −CMV cohorts (Figure 4A-B). Second, we measured the proportion of polyfunctional (interferon γ [IFNγ] + tumor necrosis factor [TNF]) CMV-peptide–responsive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after transplant35 in each cohort (Figure 4C-D). These 2 assays demonstrated that CMV-reactivating patients possessed significantly more CMV-specific and CMV-responsive T cells compared with nonreactivating patients.

Figure 4.

Analysis of CMV-specific CD8+ T cells using peptide stimulation and tetramer binding. (A) Patients who were positive for HLA-A2, -B7, or -B8 were analyzed for the frequency with which they bound to appropriate CMV-specific tetramers. Representative flow cytometry analysis is shown for −CMV (left) and +CMV (right) patients. Cells were gated as follows: lymphocytes were identified in a FSC/SSC plot, out of these, singlets were isolated. From these, CD14−/CD20−/CD3+ T cells were identified and further gated on CD8+ T cells, which were analyzed for their binding to matching tetramers. (B) Left, bar graph illustrating the frequency of tetramer-binding cells from −CMV (blue) and +CMV (red) patients. Right graph, Tetramer+ cells from +CMV patients were further separated into their respective memory subsets. (C) Representative flow cytometry analysis from −CMV and +CMV patients of intracellular cytokine expression after stimulation with CMV-specific peptides. CD8+ T cells were gated as described in Figure 2A and then analyzed for the production of IFNγ and TNF. (D) Frequency of IFNγ+/TNF+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of +CMV (n = 6) and −CMV (n = 4) patients (left). Also the frequency of IFNγ+/TNF+ CD8 T cells in each of the 4 memory subsets is shown for +CMV and −CMV patients (right). *P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01 Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

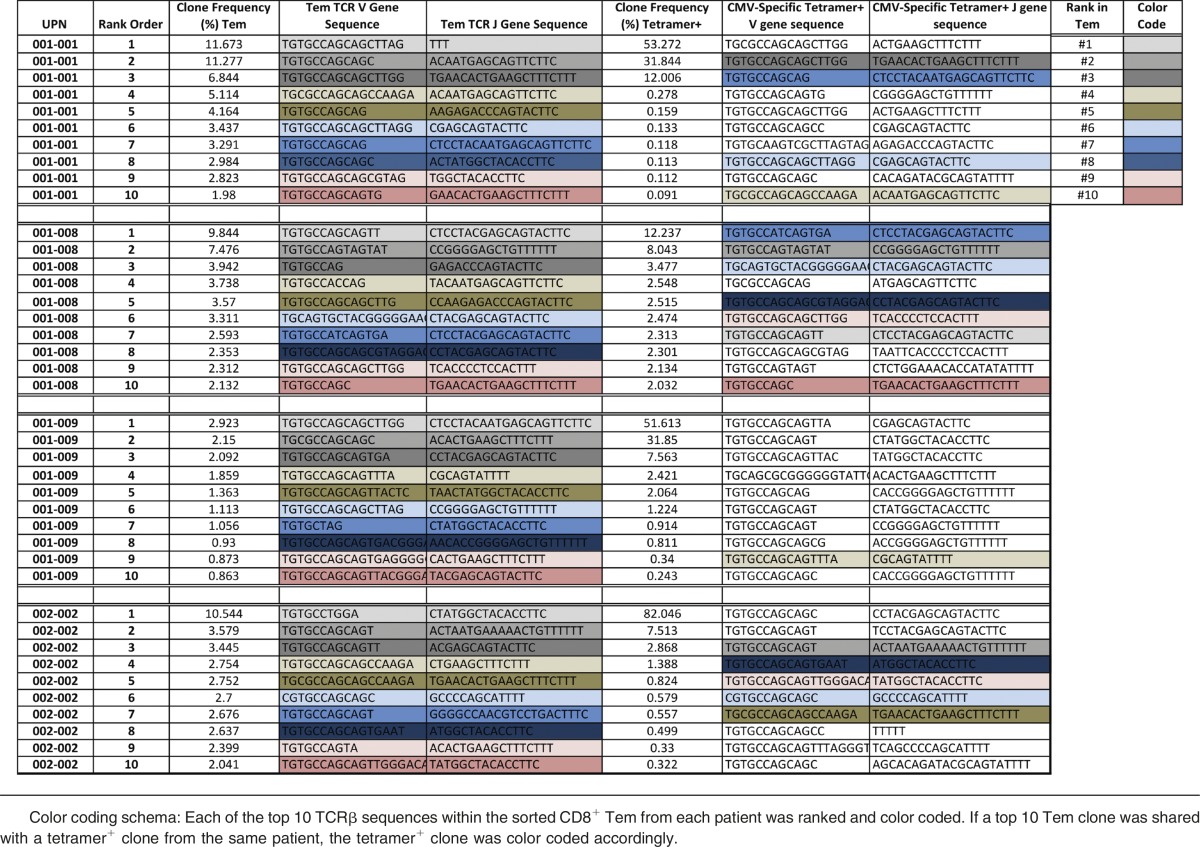

To most rigorously define the degree to which Tem clonal expansion was driven by CMV-specific T cells, we performed a tetramer-specific sorting experiment, followed by high-throughput TCRβ repertoire sequencing of these highly purified CMV-specific populations (supplemental Table 4; Figure 5A-B). Tetramer+ cells were sorted from day +365 samples from 4 CMV-reactivating patients (no cells were available from 1 patient): 001-001 (B*08 tetramer), 001-008 (A*24 tetramer), 0001-009 (A*02 tetramer), and 002-002 (A*02 + B*07 tetramers) (supplemental Table 4; supplemental Table 2). The analysis demonstrated that although each patient expanded a highly unique set of CMV-specific T-cell clones (with little clone sharing between patients) for each individual patient, there was an extremely high degree of overlap between the expanded Tem and tetramer+ clones (Figure 5A). Moreover, as shown in Figure 5B, enrichment for the Tetramer+ TCRβ clones in the most highly expanded Tem clones occurred. To further delineate this overlap, we mapped the 10 most highly expanded Tem clones onto the 10 most highly expanded tetramer+ clones (Table 3). This analysis also documented high clone sharing, which is perhaps best illustrated for patient 001-008, in which 7 of the 10 most highly expanded Tem TCRβ clones were also tetramer+. Taken together, these data provide strong molecular evidence that the expansion of CD8+ Tem in +CMV patients was driven by the clonal expansion of CMV-specific T cells. Moreover, the TCRβ sequences of the expanded and shared Tem and Tetramer+ T-cell clones from each patient (Table 3), identified 17 novel TCRβ sequences for which this study provides new evidence for linked functional expansion and CMV specificity. Although these clones likely represent only a portion of the entire CMV-specific repertoire,36,37 to our knowledge, this comparative TCRβ deep-sequencing data constitutes the first quantitative molecular link between posttransplant CD8 Tem reconstitution and CMV-specific T cells, and strongly supports a model of oligoclonal T-cell expansion in the setting of CMV reactivation.

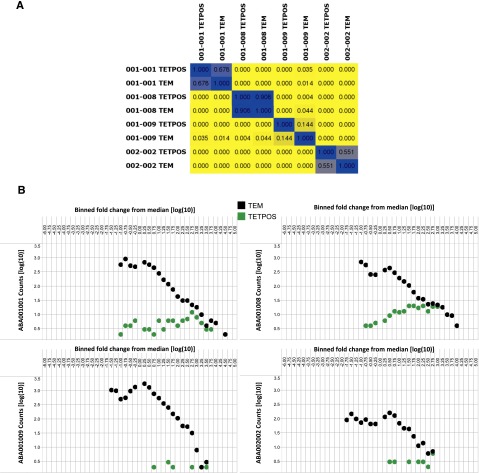

Figure 5.

Inter- and intrapatient evaluation of shared TCRβ clones between purified Tem and tetramer+ cells. (A) Color-coded pairwise TCRβ clone sharing between samples. Colors range from yellow (indicates no sharing) to blue (indicates 100% sequence sharing). This matrix depicts the degree of clone sharing between all identified TCRβ sequences in the sorted Tem and tetramer+ cells. (B) Enrichment of Tetramer+ cells in the clonally expanded Tem. Shown are dot plots for 4 +CMV patients which depict the binned frequencies for each of the TCR clones in the sorted CD8+ Tem (“TEM”; black) and sorted tetramer+ cells (“TETPOS”; green). These graphs depict the change in frequencies of productive clones, each compared with a sample-specific median frequency value. Bins represent 0.25 log(10) intervals, with binned data reported using a log10 scale. Tem clones are shown as black circles and the Tetramer+ clones are shown as green circles.

Table 3.

Rank order list of highly clonal TCR sequences from CD8+ Tem and CMV tetramer+CD8+ T cells after CMV reactivation

CMV reactivation is associated with holes in the underlying TCR repertoire, despite the CMV-specific TCEs

Although previously available technologies were able to document the impact of CMV reactivation on the clonality of the T-cell repertoire,38,39 these methods (including flow cytometry–based V-J tracking and spectratyping) are not sensitive or specific enough to interrogate the TCR landscape that underlies the highly clonally expanded CMV-specific T-cell clones. In the current study, we were able to intensively probe, for the first time, the impact of CMV reactivation on the CD8 Tem TCR landscape in toto and, specifically, to determine whether CMV reactivation was associated with specific deficits or “holes” in the repertoire. To test this hypothesis, we first created 2 reference V-J family distributions: (1) a reference repertoire derived from unique CD8 Tnaive clones of 7 healthy adults between the ages of 26 and 57 years (supplemental Table 5) which was termed the VJr and (2) a reference derived from naive CD8 T cells of the transplanted patients at day +365 (which was termed the VJr-transplant). The rationale for the choice of Tnaive to create the VJrs was that a healthy adult Tnaive repertoire would be expected to be the most representative of the breadth of V-J fractions (rather than deriving the VJr from memory subsets, which, even in normal individuals, would be expected to display skewing for selected V-J fractions given previous antigen experience). To estimate the number of holes in the Tem compartment of each patient, we subtracted the V-J family distribution for each of the patient-specific query repertoires (VJq, see supplemental Methods) from either the VJr or the VJr-transplant. This exposed deficiencies in the former relative to each reference, and holes were deemed to exist in V-J families where such deficiencies exceeded the mean for VJr. Hole analysis was confined to the Tem compartment (instead of the Tnaive) because it was only in the CD8 Tem that TCEs occurred (Figures 3 and 5; Table 3) and, thus, it was in this compartment that the issue of holes was most relevant. As shown in Figure 6A-D, CMV reactivation was associated with a compromised CD8 Tem TCR repertoire, in which the TCR repertoire of +CMV patients demonstrated significantly more holes than were present in −CMV patients.

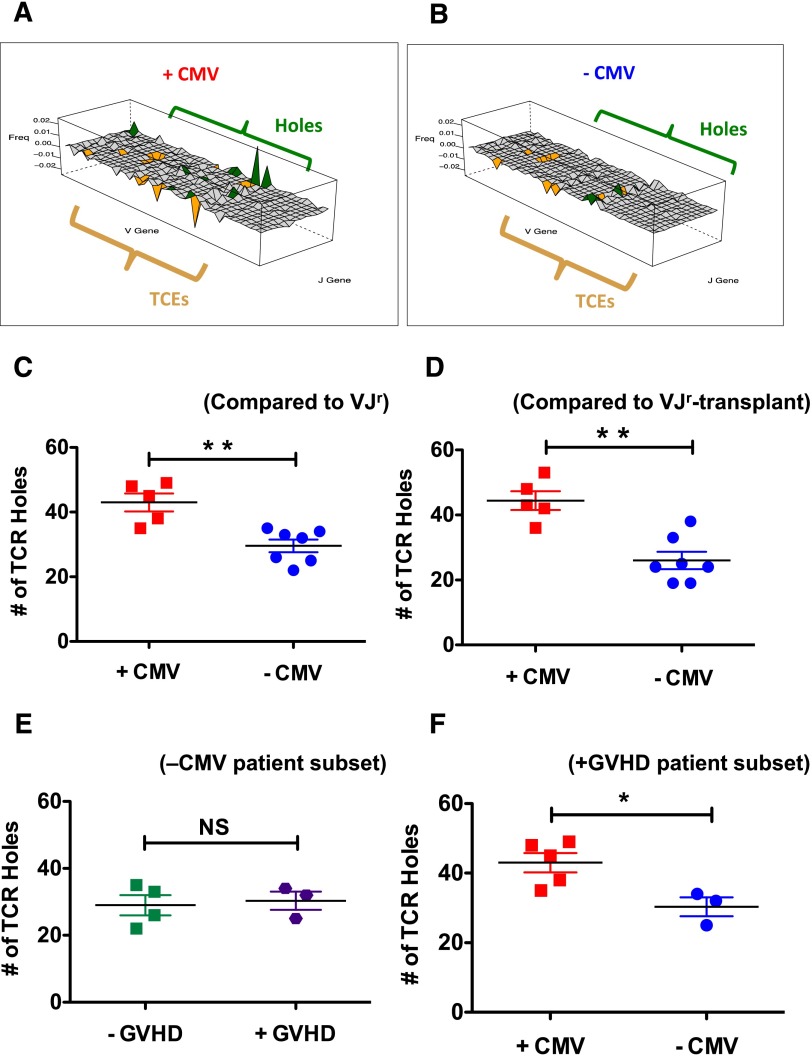

Figure 6.

Impact of CMV reactivation on CD8 Tem TCR repertoire holes. (A-B) For panels A-B, V, and J genes are represented along the x-y axes, whereas the difference in the V-J–specific proportions of unique clones are represented along the z-axis and labeled “Freq.” TCE and holes analysis was performed as described in “Methods.” Panels A and B depict wireframe 3-dimensional graphs (created using the Lattice graphics package in R) for 2 representative patients (001-008, panel A and 001-005, panel B). Both TCEs and holes in the TCR repertoire are depicted in these graphs, with V-J families in orange depicting TCEs and those in green depicting holes. Those families shown in light gray are already sparse in the VJr and thus were not evaluated for holes. (C) Summary analysis showing the mean number of holes in the CD8 Tem from the +CMV (red squares) and −CMV (blue circles) patients using the VJr. **P < .01. (D) Summary analysis showing the mean number of holes in the CD8 Tem from the +CMV (red) and −CMV (blue) patients using the VJr-transplant. **P < .01. (E) Analysis of the number of holes in −CMV patients that either did not develop GVHD (green squares, left) or did develop GVHD (purple hexagons, right) compared with the VJr. P = 1.0. (F) Analysis of the number of holes in +GVHD patients that either did reactivate CMV (red squares) or did not reactivate CMV (blue circles) compared with the VJr. *P < .05.

To investigate the potential confounding contribution of GVHD to holes in the repertoire, 2 additional analyses were performed. First, as shown in Figure 6E, −CMV patients were divided into those that did not develop significant aGVHD or cGVHD (patients 001-002, 002-001, 003-001, 004-001) and those that did develop significant GVHD (patients 001-005, 001-006, 003-003). As shown in the figure, this analysis documented no difference in the number of holes in −CMV patients based on GVHD status. Second, as shown in Figure 6F, we compared the number of holes in the subset of patients who all developed significant aGVHD or cGVHD, based on their CMV status, comparing +GVHD/+CMV patients (001-001, 001-008, 001-009, 002-002, 003-002) to +GVHD/−CMV patients (001-005, 001-006, 003-003). As shown in the figure, this subset analysis recapitulated the results in Figure 6C-D, documenting more holes in the +CMV/+GVHD patients compared with the −CMV/+GVHD patients. This constitutes the first exhaustive analysis of the underlying TCR repertoire after CMV reactivation, and provides the strongest evidence to date for significant molecular immune compromise in these patients.

CMV reactivation is associated with reduced Tnaive and thymic output after transplant

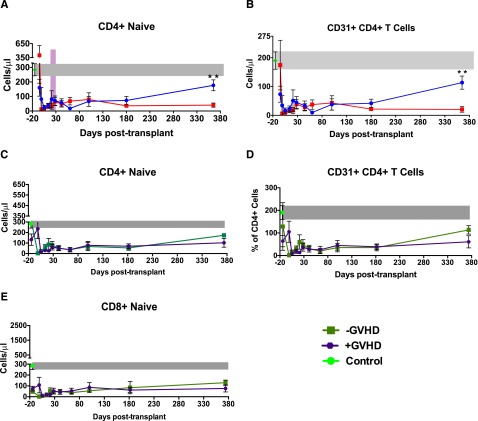

Given the observed defects in the TCR repertoire in the setting of CMV reactivation, we queried our data set to investigate whether a connection existed between reactivation and naive T-cell reconstitution as well as thymic output. We found that although patients reactivating CMV demonstrated specific expansion of CD8 Tem (Figure 2B-C), they demonstrated a global contraction of both CD4 and CD8 Tnaive (Figures 2B and 7A). In addition, as shown in Figure 7B, these patients demonstrated a progressive loss of CD31+CD4+ Tnaive, a subpopulation that has been previously shown to be enriched in new thymic emigrants.40,41 These results are consistent with thymic compromise in CMV-reactivating patients, an observation that has previously been shown in humanized murine models.42,43 Although Figures 2B and 7A-B document the impact of CMV reactivation on Tnaive reconstitution, when patients were dichotomized by the presence or absence of GVHD, no such correlation with Tnaive reconstitution was observed (Figure 7C-E).

Figure 7.

Impact of CMV reactivation and GVHD on the reconstitution of CD4+ Tnaive and CD31+ recent thymic emigrants. (A) Longitudinal analysis of the reconstitution of CD4+ Tnaive. Data are mean ± SEM in +CMV patients (n = 7), −CMV patients (n = 10), and healthy controls (n = 10). Also shown is the mean day of CMV reactivation (±SEM), depicted as a purple bar. (B) Longitudinal analysis of the reconstitution of CD31+/CD4+ recent thymic emigrants. Data are mean ± SEM in +CMV (n = 7), −CMV patients (n = 10), and healthy controls (n = 10). *P ≤ .05; **P ≤ .01; NS, nonsignificant; Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (C) Longitudinal analysis of the reconstitution of CD4+ Tnaive dichotomized based on GVHD status. Data are mean ± SEM in +GVHD patients (purple circles, n = 10), −GVHD patients (green squares, n = 7), and healthy controls (green circle and gray bar, n = 10). (D) Longitudinal analysis of the reconstitution of CD31+/CD4+ recent thymic emigrants dichotomized based on GVHD status. Data are mean ± SEM in +GVHD patients (purple circles, n = 10), −GVHD patients (green squares n = 7), and healthy controls (green circle and gray bar, n = 7). (E) Longitudinal analysis of the reconstitution of naive CD8+ T cells dichotomized based on GVHD status. Data are mean ± SEM in +GVHD patients (purple circles, n = 10), −GVHD patients (green squares, n = 7), and healthy controls (green circle and gray bar, n = 10).

Discussion

We have performed an analysis of the impact of CMV reactivation on posttransplant immune reconstitution at an unprecedented level of cellular and molecular detail. Given that immune reconstitution must occur de novo in HSCT patients, and that these patients are at high risk for CMV reactivation, studying this patient population with the tools of multiparameter flow cytometry, cell sorting, tetramer-based cell purification, and TCRβ deep sequencing provides a rigorous time-collapsed experiment on the impact of CMV on global immune phenotype and function. Moreover, the ability to correlate changes in T-cell composition and reconstitution with the inflection point of viral reactivation in these patients further strengthens the mechanistic links that can be made between CMV reactivation and immune homeostasis. Although other reactivating viruses (eg, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus) were not studied, and may also impact immune reconstitution, these experiments provided quantitative molecular evidence for CMV-specific T-cell clonal expansion and, importantly, for the development of holes in in the underlying T-cell repertoire in the setting of CMV reactivation.

In this study, 17 patients underwent detailed longitudinal immune analysis, which included both phenotypic and functional assays, as well as exhaustive TCRβ deep sequencing of sorted Tem, Tnaive, and Tetramer+ cells. In addition, 10 healthy controls were used as a comparator group for the longitudinal flow cytometric analysis and an additional 7 healthy controls were used to create the reference TCRβ repertoire. Although the number of transplanted patients that were exhaustively analyzed in this study is still relatively small, several factors strengthen the conclusions that we have been able to draw: first, each of the patients underwent detailed longitudinal analysis, with 10 time points analyzed per patient (Figures 1-2). This provided significant intrapatient controls for the longitudinal evaluation, and allowed a detailed correlation of changes in T-cell reconstitution with the inflection point of CMV reactivation. Second, a larger cohort of 46 patients, who underwent standard day 100 CD4 and CD8 counts at our institution, were also evaluated for CD4:CD8 ratio (Figure 1F), and confirmed the results that were obtained with the 17 exhaustively analyzed patients. Given the pivotal importance of the expansion of CD8 T cells to the results in this study, this external validation was of critical importance. Finally, the depth of the analysis that we performed on the patients enrolled provided a great deal of statistical power: high statistical significance was obtained for the flow cytometric as well as the deep-sequencing results where a mean of >3 million reads per sample was obtained. Together, these support the high fidelity of the data set used in the current analysis.

Our results support a model wherein CMV reactivation can drive posttransplant T-cell reconstitution. Indeed, several of the traditional hallmarks of T-cell reconstitution, often attributed to post-HSCT immune reconstitution per se,44-51 occurred exclusively in those patients that reactivated CMV. These included the inversion of the CD4:CD8 T-cell ratio, as well as the enhanced expression of the terminal differentiation marker CD5752-55 on CD8+ T cells in the +CMV cohort.

TCRβ deep sequencing enabled measurement of the impact of posttransplant CMV reactivation on immune reconstitution at a level of detail unavailable with previous technologies. This included the identification of T-cell clonal expansions in the setting of CMV reactivation, as has been previously documented.32,56 Importantly and unique to the current study, the linkage of CD8 Tem deep sequencing with CMV Tetramer+ deep sequencing provided incontrovertible evidence that the (often extreme) expansion of CD8 Tem (Figure 2B-C) in the setting of CMV reactivation was due to patient-specific CMV-directed clones (Figure 5A-B), rather than to nonspecific global expansion of Tem.

Although the analysis of the TCEs provided several novel insights into the impact of CMV on immune reconstitution posttransplant, perhaps the most important insights concerned the TCR repertoire that lied “underneath” the clonal expansions. Thus, detailed molecular analysis of this repertoire in toto has been previously unattainable, given technical limitations of TCR spectratyping or targeted sequencing. However, the deep-sequencing techniques applied in this study have allowed us to evaluate in detail the structure of the entire TCR repertoire and the impact of CMV reactivation on this structure. Given the documented existence of CD8 Tem TCEs in the setting of CMV reactivation, 2 mutually exclusive scenarios with respect to the remainder of the TCR repertoire were possible: In the first scenario, TCEs exist, but do not alter the topology of the underlying repertoire, implying intact T-cell immunity despite clonal expansions. In the second, TCEs exist concomitant with defects in the underlying reservoir: this scenario predicts defects in T-cell immunity. As shown in Figure 6, in the current study, we were able to measure, for the first time, the impact of CMV-specific TCEs on the underlying CD8 Tem immune reservoir and find that there were significantly more holes in the Tem reservoir of CMV-reactivating patients than in those that did not reactivate virus. This provides the first molecular link between CMV reactivation and a detrimental impact on subsequent protective immunity in transplant patients.

The underlying cause of the defects in the TCR repertoire in +CMV HSCT patients remains unknown, but 2 possible hypotheses have been considered. In the first, the TCEs caused by CMV reactivation result in competition for T-cell “space” in a scenario in which there is a zero-sum game for the number of T-cell clones that can exist in any individual.57 Although this scenario is possible, 3 lines of evidence suggest that it is unlikely. First, mouse models have shown that the number of CD8 Tem in the mammalian host adapts according to immunologic experience.58 Second, holes in the repertoire were not observed in aging CMV-seropositive individuals (R.M., Paul Lindau, C.D., Jeanne DaGloria, Heidi Utsugi, Edus H. Warren, Stanley R. Riddell, Karen W. Makar, Cameron J. Turtle, H.S.R., manuscript submitted April 2015), providing evidence that TCEs alone do not necessitate defects in the repertoire. Finally, CMV-reactivating transplant patients demonstrated significant growth in their total CD8+ and CD8 Tem compartment (Figures 1D and 2C), suggesting a large capacity for CD8 expansion in these patients.

The second hypothesis concerns the health of the thymus in CMV-reactivating patients, and suggests that thymic damage may result in defects in T-cell immunity. Indeed, one of the unexpected observations made in the present study was that, although CMV reactivation drove a specific expansion of CD8+ Tem cells, it was associated with a global contraction of both CD4 and CD8 Tnaive, accompanied by significantly fewer CD31+CD4+ putative recent thymic emigrants.40,41 Although the addition of T-cell receptor excision circles (TREC) analysis59,60 (which was not feasible given sample constraints in the current study) would strengthen this data set, the flow cytometric observations suggest that a defect in thymopoiesis may have been linked to CMV reactivation and to the CMV-driven expansion of CD8+ Tem. Indeed, there is supportive precedent in the literature for this, as previous studies have documented that CMV can infect thymic epithelium and that activated and effector T cells can directly infiltrate and damage the thymus.43,61-63 Moreover, a previous study of young adults, thymectomized as children, showed that the combination of the lack of thymic function and CMV infection lead to dramatic changes in T-cell homeostasis.55 These data suggest the novel hypothesis that CMV-associated thymic damage may be one of the contributory mechanisms for the immune compromise that accompanies CMV reactivation after transplant.

In determining the impact of CMV reactivation on posttransplant immune reconstitution, it is critical to also consider the potential impact that GVHD can make on thymic and immune dysfunction, given the fact that GVHD and CMV reactivation are often linked. Indeed, previous studies often59,60 but not always64,65 have documented decreased TRECs in patients that have developed cGVHD. In the current study, we have documented that (1) +CMV patients had more CD8 Tem repertoire holes than −CMV patients (Figure 6A-D); (2) when a subanalysis of only patients that developed GVHD was performed, there were more holes in the CD8 Tem in the +CMV/+GVHD patients compared with the −CMV/+GVHD patients (Figure 6F); (3) in contrast, there was no increase in holes when −CMV/−GVHD patients were compared with −CMV/+GVHD patients (Figure 6E); and (4) when flow cytometric analysis of Tnaive reconstitution was dichotomized on the basis of CMV reactivation, defective reconstitution in CMV-reactivating patients was apparent (Figures 2B-C and 7A-B), but these differences were not observed when patients were dichotomized based on GVHD (Figure 7C-E). It is important to note, however, that our study was not sufficiently powered to perform the final subanalysis, to specifically determine whether patients that experienced both CMV reactivation and GVHD (often linked together) displayed more repertoire defects than patients who had reactivated CMV but had not developed GVHD. Given the evidence in the current study for CMV-induced TCEs and holes in the CD8 Tem reservoir, and previous data supporting the impact of GVHD on thymic dysfunction,59,60 we believe that it is possible that there could be a combinatorial effect of both GVHD and CMV reactivation, such that patients that experience both complications would demonstrate the most severe defects in protective immunity. This represents a critical area for future analysis with a larger patient cohort.

This study has provided convincing molecular evidence that CMV is a major driver of CD8+ Tem expansion posttransplant, and for a linked appearance of defects in the CD8 Tem TCRβ repertoire amid contraction of the Tnaive compartment. The implications of this study are provocative, given newly available agents being tested for primary CMV prophylaxis during HSCT.15 Our results predict that preventing CMV reactivation will profoundly impact immune reconstitution after transplant, and that although quantitative CD8 reconstitution may be slower with CMV prophylaxis, qualitative T-cell reconstitution should be significantly improved.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Stan Riddell (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) and Dr Louis Picker (Oregon National Primate Research Center) for helpful discussions about the data.

This work was supported by the Katz Foundation, the CURE Childhood Cancer Foundation, a Food and Drug Administration grant FD004099 (L.S.K.), the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants R01 CA72669 and P01 CA 065493 (B.R.B.), and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant R01 AI081918 (B.R.B.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.S. performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; R.M., A.D.K., B.R.B., A.K.M., and H.S.R. analyzed data and wrote the paper; B.W., K.F., C.D., and J.R. analyzed data; D.T.K. performed the clinical trial and performed experiments; L.S., J. A. Cheeseman, J. A. Conger, and A. Garrett performed experiments; A. Grizzle performed the clinical trial; J.T.H., A.L., M.Q., H.J.K., and E.K.W. performed the clinical trial and wrote the paper; and L.S.K. conceived the study, performed the clinical trial, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.S.R. owns stock and receives consulting fees from Adaptive Biotechnologies. K.F. and C.D. are employees of Adaptive Biotechnologies with salary and stock options. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affliation for Linda Stempora, Jennifer A. Cheeseman, and Allan D. Kirk is Department of Surgery, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham NC.

Correspondence: Leslie S. Kean, Ben Towne Center for Childhood Cancer Research, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, WA 98101; e-mail: leslie.kean@seattlechildrens.org.

References

- 1.Guerrero A, Riddell SR, Storek J, et al. Cytomegalovirus viral load and virus-specific immune reconstitution after peripheral blood stem cell versus bone marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(1):66-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Jordan CT, Roback JD. Separating antiviral and GVHD activities of donor T cells prior to bone marrow transplantation. Immunol Res. 2004;29(1-3):209–218. doi: 10.1385/IR:29:1-3:209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Servais S, Lengline E, Porcher R, et al. Long term immune reconstitution and infection burden after mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(4):507-517. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Small TN, Cowan MJ. Immunization of hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients against vaccine-preventable diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7(2):193–203. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abu-Khader A, Krause S. Rapid monitoring of immune reconstitution after allogeneic stem cell transplantation—a comparison of different assays for the detection of cytomegalovirus-specific T cells. Eur J Haematol. 2013;91(6):534–545. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown JA, Stevenson K, Kim HT, et al. Clearance of CMV viremia and survival after double umbilical cord blood transplantation in adults depends on reconstitution of thymopoiesis. Blood. 2010;115(20):4111–4119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-244145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunse CE, Borchers S, Varanasi PR, et al. Impaired functionality of antiviral T cells in G-CSF mobilized stem cell donors: implications for the selection of CTL donor. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e77925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGoldrick SM, Bleakley ME, Guerrero A, et al. Cytomegalovirus-specific T cells are primed early after cord blood transplant but fail to control virus in vivo. Blood. 2013;121(14):2796–2803. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-453720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torelli GF, Lucarelli B, Iori AP, et al. The immune reconstitution after an allogeneic stem cell transplant correlates with the risk of graft-versus-host disease and cytomegalovirus infection. Leuk Res. 2011;35(8):1124–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boeckh M, Nichols WG. The impact of cytomegalovirus serostatus of donor and recipient before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the era of antiviral prophylaxis and preemptive therapy. Blood. 2004;103(6):2003–2008. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boeckh M, Nichols WG, Papanicolaou G, Rubin R, Wingard JR, Zaia J. Cytomegalovirus in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: Current status, known challenges, and future strategies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9(9):543-558. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Green ML, Leisenring W, Stachel D, et al. Efficacy of a viral load-based, risk-adapted, preemptive treatment strategy for prevention of cytomegalovirus disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(11):1687-1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Marty FM, Bryar J, Browne SK, et al. Sirolimus-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis protects against cytomegalovirus reactivation after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a cohort analysis. Blood. 2007;110(2):490–500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marty FM, Ljungman P, Papanicolaou GA, et al. Maribavir 1263-300 Clinical Study Group. Maribavir prophylaxis for prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in recipients of allogeneic stem-cell transplants: a phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(4):284–292. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marty FM, Winston DJ, Rowley SD, et al. CMX001-201 Clinical Study Group. CMX001 to prevent cytomegalovirus disease in hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(13):1227–1236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boeckh M. Complications, diagnosis, management, and prevention of CMV infections: current and future. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:305-309. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Ljungman P, Hakki M, Boeckh M. Cytomegalovirus in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24(2):319–337. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green ML, Leisenring WM, Xie H, et al. CMV reactivation after allogeneic HCT and relapse risk: evidence for early protection in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;122(7):1316–1324. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-487074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gratama JW, Boeckh M, Nakamura R, et al. Immune monitoring with iTAg MHC Tetramers for prediction of recurrent or persistent cytomegalovirus infection or disease in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: a prospective multicenter study. Blood. 2010;116(10):1655–1662. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-273508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozdemir E, St John LS, Gillespie G, et al. Cytomegalovirus reactivation following allogeneic stem cell transplantation is associated with the presence of dysfunctional antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2002;100(10):3690–3697. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gratama JW, Brooimans RA, van der Holt B, et al. Monitoring cytomegalovirus IE-1 and pp65-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses after allogeneic stem cell transplantation may identify patients at risk for recurrent CMV reactivations. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2008;74(4):211–220. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gratama JW, van Esser JW, Lamers CH, et al. Tetramer-based quantification of cytomegalovirus (CMV)-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in T-cell-depleted stem cell grafts and after transplantation may identify patients at risk for progressive CMV infection. Blood. 2001;98(5):1358–1364. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koura DT, Horan JT, Langston AA, et al. In vivo T cell costimulation blockade with abatacept for acute graft-versus-host disease prevention: a first-in-disease trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(11):1638-1649. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Carlson CS, Emerson RO, Sherwood AM, et al. Using synthetic templates to design an unbiased multiplex PCR assay. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2680. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robins HS, Campregher PV, Srivastava SK, et al. Comprehensive assessment of T-cell receptor beta-chain diversity in alphabeta T cells. Blood. 2009;114(19):4099–4107. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-217604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robins HS, Srivastava SK, Campregher PV, et al. Overlap and effective size of the human CD8+ T cell receptor repertoire. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(47):47ra64. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lê Cao KA, Boitard S, Besse P. Sparse PLS discriminant analysis: biologically relevant feature selection and graphical displays for multiclass problems. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan N, Shariff N, Cobbold M, et al. Cytomegalovirus seropositivity drives the CD8 T cell repertoire toward greater clonality in healthy elderly individuals. J Immunol. 2002;169(4):1984–1992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadrup SR, Strindhall J, Køllgaard T, et al. Longitudinal studies of clonally expanded CD8 T cells reveal a repertoire shrinkage predicting mortality and an increased number of dysfunctional cytomegalovirus-specific T cells in the very elderly. J Immunol. 2006;176(4):2645–2653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verfuerth S, Peggs K, Vyas P, Barnett L, O’Reilly RJ, Mackinnon S. Longitudinal monitoring of immune reconstitution by CDR3 size spectratyping after T-cell-depleted allogeneic bone marrow transplant and the effect of donor lymphocyte infusions on T-cell repertoire. Blood. 2000;95(12):3990–3995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu CJ, Chillemi A, Alyea EP, et al. Reconstitution of T-cell receptor repertoire diversity following T-cell depleted allogeneic bone marrow transplantation is related to hematopoietic chimerism. Blood. 2000;95(1):352–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Heijst JW, Ceberio I, Lipuma LB, et al. Quantitative assessment of T cell repertoire recovery after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nat Med. 2013;19(3):372–377. doi: 10.1038/nm.3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ekström M. Quantifying spatial patterns of landscapes. Ambio. 2003;32(8):573–576. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-32.8.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gastwirth JL. The estimation of the Lorenz curve and Gini index. Rev Econ Stat. 1972:306–316. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komanduri KV, Donahoe SM, Moretto WJ, et al. Direct measurement of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to CMV in HIV-1-infected subjects. Virology. 2001;279(2):459–470. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lacey SF, Villacres MC, La Rosa C, et al. Relative dominance of HLA-B*07 restricted CD8+ T-lymphocyte immune responses to human cytomegalovirus pp65 in persons sharing HLA-A*02 and HLA-B*07 alleles. Hum Immunol. 2003;64(4):440–452. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(03)00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bihl F, Frahm N, Di Giammarino L, et al. Impact of HLA-B alleles, epitope binding affinity, functional avidity, and viral coinfection on the immunodominance of virus-specific CTL responses. J Immunol. 2006;176(7):4094–4101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knight A, Madrigal AJ, Grace S, et al. The role of Vδ2-negative γδ T cells during cytomegalovirus reactivation in recipients of allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;116(12):2164–2172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-255166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weekes MP, Wills MR, Sissons JG, Carmichael AJ. Long-term stable expanded human CD4+ T cell clones specific for human cytomegalovirus are distributed in both CD45RAhigh and CD45ROhigh populations. J Immunol. 2004;173(9):5843–5851. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Junge S, Kloeckener-Gruissem B, Zufferey R, et al. Correlation between recent thymic emigrants and CD31+ (PECAM-1) CD4+ T cells in normal individuals during aging and in lymphopenic children. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(11):3270–3280. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimmig S, Przybylski GK, Schmidt CA, et al. Two subsets of naive T helper cells with distinct T cell receptor excision circle content in human adult peripheral blood. J Exp Med. 2002;195(6):789–794. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komanduri KV, St John LS, de Lima M, et al. Delayed immune reconstitution after cord blood transplantation is characterized by impaired thymopoiesis and late memory T-cell skewing. Blood. 2007;110(13):4543–4551. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Numazaki K, DeStephano L, Wong I, Goldman H, Spira B, Wainberg MA. Replication of cytomegalovirus in human thymic epithelial cells. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl) 1989;178(2):89–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00203304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis CC, Marti LC, Sempowski GD, Jeyaraj DA, Szabolcs P. Interleukin-7 permits Th1/Tc1 maturation and promotes ex vivo expansion of cord blood T cells: a critical step toward adoptive immunotherapy after cord blood transplantation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(13):5249–5258. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thiant S, Labalette M, Trauet J, et al. Plasma levels of IL-7 and IL-15 after reduced intensity conditioned allo-SCT and relationship to acute GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46(10):1374–1381. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Velden AM, Claessen AM, van Velzen-Blad H, et al. Vaccination responses and lymphocyte subsets after autologous stem cell transplantation. Vaccine. 2007;25(51):8512–8517. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Komatsuda M. Changes of lymphocyte subsets in leukemia patients who received allogenic bone marrow transplantation. Acta Med Okayama. 1991;45(4):257–265. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roberts MM, To LB, Gillis D, et al. Immune reconstitution following peripheral blood stem cell transplantation, autologous bone marrow transplantation and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1993;12(5):469–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hebib NC, Déas O, Rouleau M, et al. Peripheral blood T cells generated after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: lower levels of bcl-2 protein and enhanced sensitivity to spontaneous and CD95-mediated apoptosis in vitro. Abrogation of the apoptotic phenotype coincides with the recovery of normal naive/primed T-cell profiles. Blood. 1999;94(5):1803–1813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maury S, Mary JY, Rabian C, et al. Prolonged immune deficiency following allogeneic stem cell transplantation: risk factors and complications in adult patients. Br J Haematol. 2001;115(3):630–641. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pavletic ZS, Joshi SS, Pirruccello SJ, et al. Lymphocyte reconstitution after allogeneic blood stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21(1):33–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gorochov G, Debré P, Leblond V, Sadat-Sowti B, Sigaux F, Autran B. Oligoclonal expansion of CD8+ CD57+ T cells with restricted T-cell receptor beta chain variability after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1994;83(2):587–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horiuchi T, Hirokawa M, Kawabata Y, et al. Identification of the T cell clones expanding within both CD8(+)CD28(+) and CD8(+)CD28(-) T cell subsets in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic cell grafts and its implication in post-transplant skewing of T cell receptor repertoire. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27(7):731–739. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mollet L, Fautrel B, Leblond V, et al. Leukemic CD3+ LGL share functional properties with their CD8+ CD57+ cell counterpart expanded after BMT. Leukemia. 1999;13(2):230–240. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sauce D, Larsen M, Fastenackels S, et al. Evidence of premature immune aging in patients thymectomized during early childhood. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(10):3070–3078. doi: 10.1172/JCI39269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB, et al. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med. 2005;202(5):673–685. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mekker A, Tchang VS, Haeberli L, Oxenius A, Trkola A, Karrer U. Immune senescence: relative contributions of age and cytomegalovirus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(8):e1002850. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vezys V, Yates A, Casey KA, et al. Memory CD8 T-cell compartment grows in size with immunological experience. Nature. 2009;457(7226):196–199. doi: 10.1038/nature07486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lewin SR, Heller G, Zhang L, et al. Direct evidence for new T-cell generation by patients after either T-cell-depleted or unmodified allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantations. Blood. 2002;100(6):2235–2242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weinberg K, Blazar BR, Wagner JE, et al. Factors affecting thymic function after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;97(5):1458–1466. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Agus DB, Surh CD, Sprent J. Reentry of T cells to the adult thymus is restricted to activated T cells. J Exp Med. 1991;173(5):1039–1046. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.5.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krenger W, Holländer GA. The immunopathology of thymic GVHD. Semin Immunopathol. 2008;30(4):439–456. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mocarski ES, Bonyhadi M, Salimi S, McCune JM, Kaneshima H. Human cytomegalovirus in a SCID-hu mouse: thymic epithelial cells are prominent targets of viral replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(1):104–108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Storek J, Joseph A, Dawson MA, Douek DC, Storer B, Maloney DG. Factors influencing T-lymphopoiesis after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73(7):1154–1158. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200204150-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Storek J, Joseph A, Espino G, et al. Immunity of patients surviving 20 to 30 years after allogeneic or syngeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2001;98(13):3505–3512. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]