Abstract

The rapid identification of antimicrobial resistance is essential for effective treatment of highly resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Whole-genome sequencing provides comprehensive data on resistance mutations and strain typing for monitoring transmission, but unlike for conventional molecular tests, this has previously been achievable only from cultures of M. tuberculosis. Here we describe a method utilizing biotinylated RNA baits designed specifically for M. tuberculosis DNA to capture full M. tuberculosis genomes directly from infected sputum samples, allowing whole-genome sequencing without the requirement of culture. This was carried out on 24 smear-positive sputum samples, collected from the United Kingdom and Lithuania where a matched culture sample was available, and 2 samples that had failed to grow in culture. M. tuberculosis sequencing data were obtained directly from all 24 smear-positive culture-positive sputa, of which 20 were of high quality (>20× depth and >90% of the genome covered). Results were compared with those of conventional molecular and culture-based methods, and high levels of concordance between phenotypical resistance and predicted resistance based on genotype were observed. High-quality sequence data were obtained from one smear-positive culture-negative case. This study demonstrated for the first time the successful and accurate sequencing of M. tuberculosis genomes directly from uncultured sputa. Identification of known resistance mutations within a week of sample receipt offers the prospect for personalized rather than empirical treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis, including the use of antimicrobial-sparing regimens, leading to improved outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

The global incidence of multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), and totally drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) has risen over the last decade (1), making it increasingly important to rapidly and accurately detect resistance. The gold standard for antimicrobial resistance testing relies on bacterial culture, which can take upwards of several weeks for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Molecular tests, such as the Xpert (MTB/RIF) and line probe assays, which can be used directly on sputum have improved identification of MDR M. tuberculosis but are able to identify only limited numbers of specific resistance mutations (2, 3).

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of bacterial genomes allows simultaneous identification of all known resistance mutations as well as markers with which transmission can be monitored (4). WGS of M. tuberculosis provides resolution superior to that of other current methods such as spoligotyping and mycobacterial interspersed repetitive-unit–variable-number tandem-repeat (MIRU-VNTR) analysis for strain genotyping (5), and its usefulness in defining outbreaks has been demonstrated previously (6–9). Currently, however, WGS of M. tuberculosis requires prior bacterial enrichment by culturing and most outbreak studies have therefore been retrospective (6–8). Recently, WGS of M. tuberculosis has been achieved from a 3-day-old mycobacterial growth indicator tube (MGIT) culture, thus reducing the time from sample receipt to resistance testing to less than a week (10). However, with the mean time to a positive MGIT culture being 14 days (11, 12), most WGS results are not available for more than 2 weeks, which is too long a delay before starting therapy. Moreover, the extent to which even limited culture perturbs the original sample composition remains unknown, especially in cases where a patient is suffering from infection with multiple strains, a common occurrence in developing countries, where it has been observed in up to 19% of cases (13). As described here, we utilized the oligonucleotide enrichment technology SureSelectXT (Agilent) method to obtain the first M. tuberculosis genome sequences directly from both smear-positive and smear-negative sputum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

A total of 58 routine diagnostic samples from the United Kingdom and Lithuania, including 24 smear-positive sputum specimens from pulmonary TB patients and 24 matching cultures (grown on Middlebrook 7H11 plates from the relevant sputum specimens; see below) and 10 sputum samples from patients who had previously been diagnosed with TB and which failed to grow in culture, were analyzed. Further details can be found in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Sputum was visually scored at 1+ to 3+ for acid-fast bacilli (AFB). Sequencing and subsequent analysis were processed in a blind manner with respect to smear and resistance results.

Bacteriological methods.

Prior to treatment, all sputum specimens were kept frozen at −20°C. Bacteriological culture samples were processed as follows. Samples were decontaminated using N-acetyl-l-cysteine/NAOH (1% NaOH final concentration) and resuspended after centrifugation in 2 ml phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). Subsequently, 0.1 ml of the suspension was used for inoculation onto Middlebrook 7H11 media, while the remaining suspension was used for extraction of the genomic DNA directly from sputum (see below). Plates were incubated at 37°C for at least 4 weeks or until visible growth was obtained.

DNA extraction from sputum.

The bacterial suspension used for inoculation was repelleted by centrifugation at 16,000 × g. Supernatants were decanted, and pelleted cells were resuspended in 0.3 ml Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer and transferred to sterile 2-ml screw-cap tubes containing ∼250 μl of 0.1-mm-diameter glass beads (Becton Dickinson). Microorganisms were heat killed at 80°C for 50 min and then frozen at −20°C; after thawing, the tubes were subjected to vortex mixing for 3 min and centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 × g. The supernatant was transferred to a clean 2-ml tube for subsequent DNA purification using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue DNA extraction kit (Qiagen) per the manufacturer's instruction. Genome copy numbers in the sputum samples were determined using an Artus M. tuberculosis RG PCR kit (Qiagen), per the manufacturer's instructions.

DNA extraction from cultures.

Two loopfuls of M. tuberculosis growth from Middlebrook 7H11 plates were transferred into 2-ml screw-cap tubes containing ∼250 μl of 0.1-mm-diameter glass beads (Becton Dickinson) and 0.3 ml of TE buffer. Subsequent processing and genomic DNA extraction and purification were done as described for the sputum samples.

Resistance profiling.

All isolates were tested for susceptibility to first-line drugs rifampin (RIF), isoniazid (INH), ethambutol (EMB), pyrazinamide (PZA), and streptomycin (STR). Isolates resistant to at least RIF and INH (i.e., representing multidrug-resistant TB [MDR-TB]) were additionally tested for susceptibility to kanamycin (KAN), amikacin (Amk), ofloxacin (OFL), capreomycin (CAP), ethionamide (ETH), prothionamide (PTH), and par-aminosalicylate sodium (PAS).

Drug susceptibility testing (DST) was carried out on an automated liquid medium-based system, Bactec MGIT960 (Becton Dickinson), using standard drug concentrations (in micrograms per milliliter) as follows: for STR, 1.0; for INH, 0.1; for RIF, 1.0; for EMB, 5.0; for PZA, 100.0; for OFL, 2.0; for Amk, 1.0; for CAP, 2.5; for KAN, 5.0; for ETH, 5.0; for PTH, 2.5; and for PAS, 4.0 (14).

Spoligotyping.

Spoligotyping was carried out as described previously using membranes with immobilized oligonucleotide probes (Ocimum Biosolutions) (15). For identification of genetic families and lineages, 43-digit binary spoligotyping codes were entered into the MIRU-VNTRplus database (www.miru-vntrplus.org) and families identified using a similarity search algorithm.

SureSelectXT target enrichment: RNA bait design.

Examples of 120-mer RNA baits spanning the length of the positive strand of the H37Rv M. tuberculosis reference genome (AL123456.3) (16) were designed using an in-house Perl script developed by the PATHSEEK consortium. The specificity of the bait was verified by BLASTn searches against the Human Genomic Plus Transcript database. The custom-designed M. tuberculosis bait library was uploaded to SureDesign and synthesized by Agilent Technologies.

SureSelectXT target enrichment: library preparation, hybridization, and Illumina sequencing.

Prior to processing, M. tuberculosis DNA samples were quantified and carrier human genomic DNA (Promega) was added to obtain a total of 3 μg of DNA input for library preparation. All DNA samples were sheared four times for 60 s each time using a Covaris S2 ultrasonicator (duty cycle, 10%; intensity setting, 4; 200 cycles per burst using frequency sweeping). The samples were then subjected to library preparation using a SureSelectXT target enrichment system for the Illumina paired-end sequencing library protocol (V1.4.1, September 2012). Prior to hybridization, eight cycles of precapture PCR were used, and ∼750 ng of amplified product was included in each hybridization (24 h, 65°C). A total of 16 cycles of postcapture PCR were performed with indexing primers. The resulting library was run on a MiSeq sequencer (Illumina) using a 600-bp reagent kit, typically in pools of 8 or 10; some sputum smear-positive 1+ samples were run in smaller pools to increase coverage. Base calling and sample demultiplexing were generated per the standard method on the MiSeq machine, producing paired FASTQ files for each sample. The raw sequencing data have been deposited on the European Nucleotide archive (upon acceptance of publication). An overview of the process is presented in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

Sequence analysis.

The samples were analyzed using a reference-based mapping approach implemented in CLC Genomics Workbench (v. 7.5). Prior to mapping, the reads were trimmed to remove low-quality sequence at the end of reads or adaptor contamination. The reads were mapped against the H37Rv genome (AL123456.3) using default parameters with the addition of a similarity threshold to remove non-M. tuberculosis reads, according to which any reads where at least 90% of the length did not match the reference by at least 90% were discarded. This was required to remove non-M. tuberculosis reads. Duplicate reads were then removed from the mapped reads, and the average depth of coverage was calculated. The percentage of on-target reads (%OTR) was calculated by counting the number of reads that were successfully mapped to H37Rv. Any reads that did not map were assumed to be off-target reads (i.e., not representative of M. tuberculosis).

Bases were called using VarScan (v 2.3.7) (17), applying high-stringency parameters, including a minimum depth of 4 reads, a minimum average quality value of 20, a P value cutoff of 99e-02, and an absence of heterozygosity at a level greater than 10%. A consensus sequence was generated where only called bases were considered, and any bases which failed quality thresholds were called as “N.” To build the phylogeny, any variants which were identified in insertion sequence (IS) elements or the PE and PPE gene families were excluded, as these regions are recognized to be prone to false-positive single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calls (8). The remaining positions (representing 92% of the genome) were then used to build a maximum likelihood tree using RAxML v 8.0.0 (18) with 100 bootstrap replicates.

Genome coverage was calculated by dividing the number of high-quality bases successfully called (per the VarScan details above) by the reference genome (H37Rv) size. “Depth of coverage” refers to the number of reads supporting a position.

Calling genotypic resistance.

Potential drug susceptibility-associated variants were detected using a custom Perl script, and positions were identified in a curated drug resistance database (http://pathogenseq.lshtm.ac.uk/rapiddrdata) (unpublished data) from bam and bcf files (19). Variants were considered if they were supported by at least 2 forward and reverse reads and had P values of at least 0.05 for strand bias and 0.001 for read-end bias, base-quality bias, and mapping-quality bias as calculated by bcftools (19). A sample was called as genotypically resistant if it had a mutation in over 10% of reads. Any mutations identified in the rRNA genes were inspected manually to exclude any that might have been the result of off-target enrichment of these highly conserved regions. Those that were found on reads that formed distinct haplotypes, where variants were found in close association with other variants on multiple reads, were excluded, as they likely belonged to non-M. tuberculosis species.

The analysis was also carried out independently on a customized version of the CLC Genomics Workbench (Qiagen-AAR), which facilitates a fully automated pipeline, including the steps of trimming, mapping to a reference, removal of duplicate mapped reads, variant calling, and cross-referencing with the resistance database (described above). Variants called using the automated workflow (using the Low Frequency Variant Detector, CLC Genomic Workbench) were considered significant if the average quality was above 30, the frequency was greater than 10%, and the forward and reverse read balance was above 0.35. Variants were inspected manually for possible contamination. The runtime using a standard laptop (Macbook Pro) was on average 1 h per sample. The resistance genotypes called were in agreement with those identified using the workflow described above.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The raw sequencing data have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive under project accession no. PRJEB9206.

RESULTS

Successful enrichment directly from sputum in both smear-positive and smear-negative tuberculosis cases.

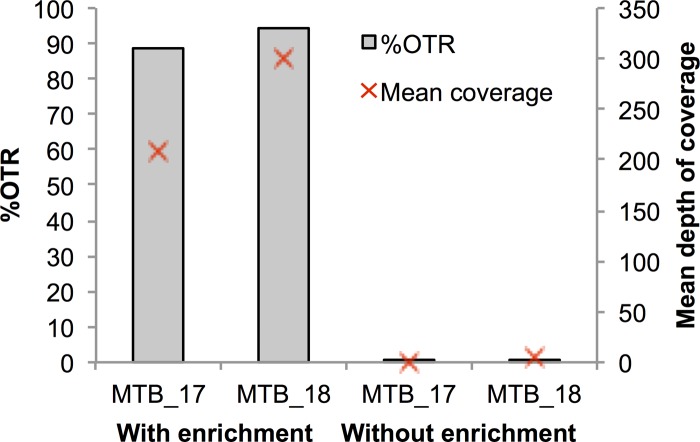

To assess the potential benefits of enrichment strategies for WGS of clinical M. tuberculosis, we compared the percentages of on-target reads (%OTR), as defined in Materials and Methods, and the mean sequencing depths for two sputum samples, each processed with and without enrichment. The average %OTR value for M. tuberculosis sequenced directly (without enrichment) from sputum was 0.3%, with 4.6× sequencing depth, compared to the results seen with enrichment, which generated a %OTR of 82%, with a mean sequencing depth of 200× (Fig. 1). Although cultured M. tuberculosis sequenced well with and without enrichment, the former gave a greater mean read depth (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Even coverage across the genome was obtained, with no bias observed for particular regions or genes (see Fig. S3).

FIG 1.

Mean coverage and percentage of on-target reads (OTR) in sequencing from sputum with and without enrichment for two samples.

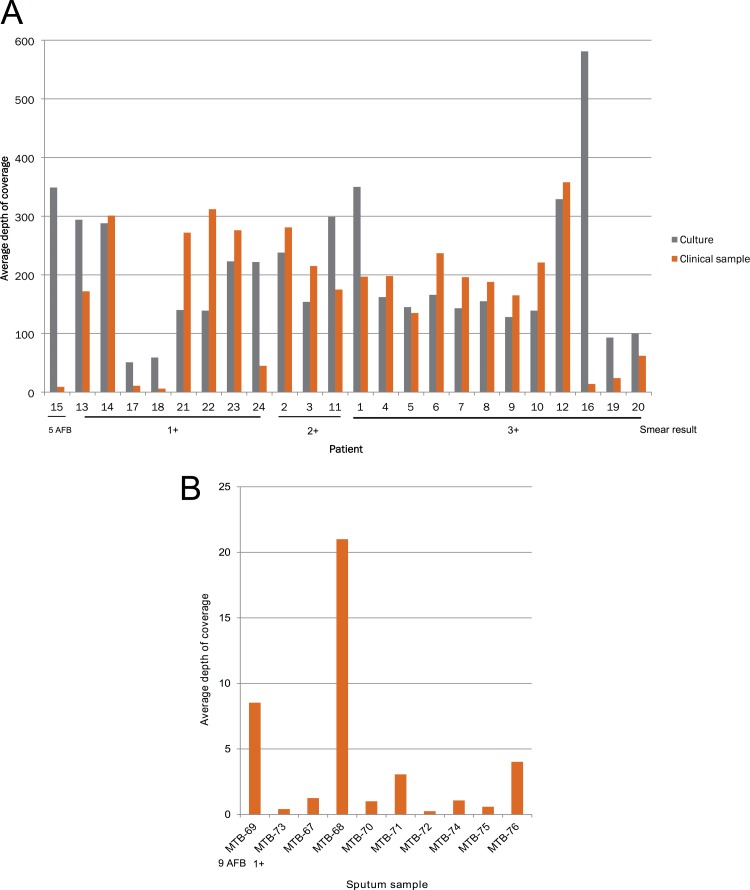

Over 98% of the M. tuberculosis genome was recovered from 20 of 24 (83%) smear-positive, culture-positive sputa. Fully complete genomes are not achievable for M. tuberculosis using short-read sequencing technology, due to the difficulties presented by repetitive regions and the PE and PPE genes (8, 20). Similar levels of genome coverage and sequencing depth were also obtained from the nonenriched matched cultures (Fig. 2). The depths of coverage obtained for four sputum samples were poor (for MTB-41, 9×; for MTB-42, 14×; for MTB-43, 6×; and for MTB-44, 11×), resulting in genome coverage of less than 90%. In the case of MTB-43 and MTB-44, which had inputs of 1 and <1 genome copies per μl, respectively (these values are out of the range of reliable standards as measured by real-time PCR), this was likely due to a low pathogen load.

FIG 2.

(A) Depth of coverage obtained for smear-positive samples from sputum and culture. (B) Depth of coverage for sputum sequence from smear-positive samples which failed to grow. The level of smear positivity is shown, with the remaining samples being smear negative.

In addition, we were able to enrich and sequence M. tuberculosis from two smear-positive but culture-negative sputum samples (MTB-69 and MTB-73), successfully recovering sequence data from the former with a sequence depth of 8.5× (Fig. 2). We also attempted to sequence eight culture-negative, smear-negative sputum samples, which were obtained from previously diagnosed patients (MTB-67 and -72 and MTB-74 and -76). Surprisingly, for two of these samples, MTB-68 and MTB-76, we obtained high-quality M. tuberculosis sequence data, with average depths of coverage of 9× and 22×, respectively (Fig. 2). For five of the samples, we detected low numbers of M. tuberculosis reads (<1× depth of coverage), which might represent a very low load or residual DNA from dead bacilli. No full-length M. tuberculosis reads were detected in the final sample (MTB-72).

Concordance between genotypes obtained from matched pairs of culture and sputum samples.

Using the high-quality variable sites called, we constructed a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree. Six samples, with less than 90% genome and SNP position coverage, had an unusual phylogenetic positioning, close to nodes on the tree (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), a pattern consistent with a lack of informative sites. With these samples excluded, the resulting robust phylogeny revealed that, for all of the matched pairs, identical or near-identical genomes were obtained from culture and sputa (see Fig. S5).

Concordance between resistance phenotype and genotype.

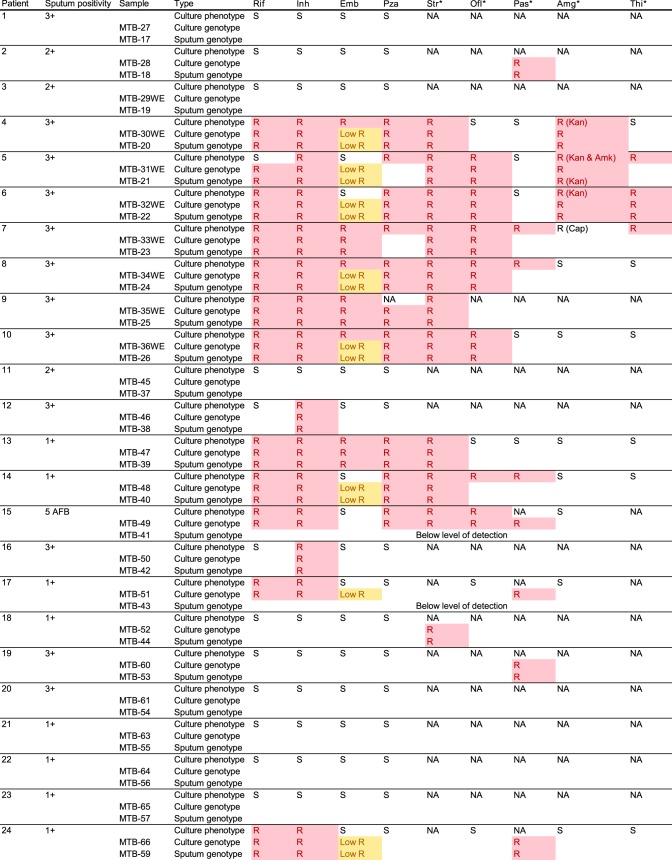

For the 24 matched pairs, we sought to identify the genetic resistance determinants which could explain their antibiotic susceptibility profile. Predicted resistance mutations were 100% concordant between the sequences obtained from culture and those obtained from sputa (Fig. 3), with the exception of the low-coverage samples (MTB-41, MTB-42, MTB-43, and MTB-44) for which we were unable to confidently call variants at many of the targeted loci.

FIG 3.

Resistance phenotype and genotype of matched pairs. R, a mutation exists at a level of greater than 10%. Low R, a mutation in codon 306 of the embB gene which is thought to confer low-level resistance to ethambutol. NA, not applicable, as phenotype was not tested. Rif, rifampin; Inh, isoniazid; Emb, ethambutol; Pza, pyrazinamide; Str, streptomycin; Ofl, ofloxacin (fluoroquinolones); Pas, para-aminosalicylic acid; Amg, aminoglycosides; Thi, thionamides. The asterisks indicate second-line antibiotics.

The predicted resistance genotype agreed well with the phenotypic resistance profiles, with a possible resistance-conferring mutation being detected in 88% (59/67) of phenotypically resistant cases and no known resistance mutation in 94% (72/77) of sensitive cases. Two phenotypically pyrazinamide-resistant isolates (collected from patients 7 and 14), both belonging to the Ural lineage, were identified as having a large (8.64-kb) chromosomal deletion resulting in the removal of the pncA gene, the activator of the prodrug pyrazinamide, plus 10 surrounding genes (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material).

Four samples were phenotypically ethambutol sensitive but had a mutation in codon 306 of the embB gene. This mutation has been observed to cause both low-level and high-level resistance to ethambutol and so may lead to a borderline phenotype (21, 22). The isolate from patient 15 was phenotypically ethambutol sensitive but had a Q497R mutation in the embB gene, which has previously been associated with sensitivity both in clinical isolates (23) and through the construction of isogenic mutants (24), and so was discounted. Similarly, the isolate from patient 2 was phenotypically sensitive to isoniazid but had a G269S mutation in the kasA gene, which has also previously been found in sensitive isolates (25). The isolate from patient 5 was also phenotypically sensitive to rifampin, notwithstanding the presence of a L452P (codon 533 in E. coli) mutation in the rpoB gene. This mutation has also been associated with both high and low levels of rifampin resistance in the literature (26). A M. tuberculosis strain isolated from this patient in the past had been found to be rifampin resistant, suggesting either that this mutation results in a borderline phenotype or, alternatively, that a mixture of rifampin-resistant and -sensitive strains could have been present in this patient, although this was not detected in the sequencing data obtained from either the sputum or culture. The remaining eight samples were phenotypically resistant, with an absence of any described or speculative causative genetic mutations. Five of these were phenotypically resistant to second-line drugs for which the genetic basis of resistance is less well understood. These discrepancies highlight that the current limitation on our ability to detect resistance via WGS is not the detection itself but is rather the lack of data on the genetic correlates of resistance.

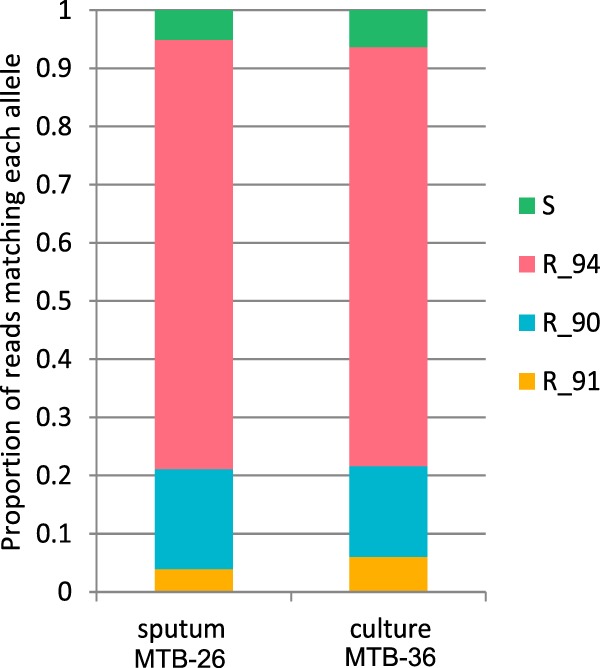

Any alleles detected at a low (<10%) level were excluded from this analysis due to the potential problem of carryover on the sequencing platform which has been previously described (27). Further work will be required to quantify the validity of these mutations or to assess their clinical significance. In the majority of cases, resistance alleles had reached fixation or near-fixation in both culture and sputum samples, as they were found in 98% to 100% of the reads. In patient 10, however, significant heterozygosity was detected, with more than one allele being detected at a level of greater than 10% at a single position. A mixture of three different resistance alleles and one sensitive allele was detected within a single codon of the gyrA gene (Fig. 4). Remarkably, almost identical proportions were detected in the corresponding culture sample.

FIG 4.

Heteroresistance in gyrA in patient 10. R, resistant allele with suffix indicating codon position; S, absence of resistant allele.

DISCUSSION

Whole-genome sequencing of bacteria has been shown to provide comprehensive data on antimicrobial resistance which could be used to inform antimicrobial prescribing. However, current methods which rely on culturing the organism prior to sequencing are slow and so are of limited use in patient management. As a result, initial antimicrobial prescribing for resistant M. tuberculosis strains remains largely empirical in the early phase of treatment. Currently, MDR M. tuberculosis can be detected rapidly on the Xpert MTB/RIF system, but a rapid test for extensively drug-resistant (XDR) cases is unavailable. As Xpert (MTB/RIF) focuses only on rpoB (RIF), mutations resulting in unusual resistance patterns where strains are rifampin sensitive but show other resistance, such as the isoniazid-resistant, rifampin-sensitive case included in this study, are missed. Here, we describe the recovery and sequencing of near-complete genomes directly from 81% (21/26) of smear-positive sputa, including those staining for low (+1) numbers of acid-fast bacilli (AFB), within a time scale (up to 96 h) that could allow personalized antimicrobial treatment for both sensitive and resistant cases, including XDR TB.

M. tuberculosis is particularly appropriate for the use of diagnostic WGS with enrichment, as, unlike the majority of pathogenic organisms, M. tuberculosis has a well-characterized clonal nature, with relatively low levels of sequence variation, and does not undergo recombination or horizontal transfer (28); thus, a stable set of oligonucleotide baits can be created and sequence data can be mapped against a reference genome. We have demonstrated that enrichment of M. tuberculosis provides sequencing data that match the quality and quantity of data obtained via sequencing from culture. Moreover, we were able to recover high-quality M. tuberculosis sequencing data from one smear-positive case and one smear-negative case, both from patients who had received anti-TB therapy and whose isolates has failed to grow in culture. However, it is difficult to interpret these cases without further clinical information. Smear-positive culture-negative cases are most commonly thought to be due to the ongoing persistence of dead bacilli in sputum samples (29). For this reason, previously treated cases are currently not recommended for use on PCR-based diagnostic systems, such as Xpert, that cannot distinguish between dead or live bacilli. Further investigation will be required to assess the suitability of targeted enrichment in the context of different clinical scenarios. There were four smear-positive, culture-positive cases where less-optimal data were obtained from sputa, although we envisage that sequencing of such low-titer samples could be improved through further optimization or increased sequencing depth. It is worth noting that these samples were deemed failures based on commonly used SNP calling thresholds employed by others in the field. Further work will be required to robustly establish parameters that are sufficient for clinical use and interpretation, particularly in considering low-frequency variants.

Sequencing directly from the clinical sample may reduce any possible biases associated with culture. The overall presence of heteroresistance in this study was low (one patient), with most resistance-conferring mutations observed to be close to fixation; i.e., the entire sampled population was resistant. However, mixed infections have been observed to be much more prevalent, especially in HIV-positive patients, in settings of endemicity (14, 30–32). The detection of these heteroresistant cases not only is important for our understanding of how resistance evolves but could have an impact on clinical management (33). Further studies are required to explore any bias on genetic diversity that may be introduced by culture, particularly in the context of mixed-strain infections.

A disadvantage of the approach presented here is that it is relatively expensive, currently costing approximately $350 per sample in our laboratory. It also requires skills and machinery currently not available in most microbiological laboratories. An alternative and cheaper rapid sequencing-based approach would be to perform deep sequencing of total DNA from sputum samples without enrichment. The authors of a recent study found they could recover M. tuberculosis reads from eight smear- and culture-positive samples (34). However, in agreement with our study, they obtained a very low (<1×) depth of coverage in the absence of enrichment, so the usefulness of this approach is likely to be limited to detection and it is unlikely to provide the detailed genotype and resistance information that is presented here in a high-throughput manner.

In summary, we have demonstrated whole M. tuberculosis genome sequencing directly from smear-positive, culture-positive sputa within a clinically relevant time frame that would enable proactive patient management. The quality of sequence data allowed us to accurately call mutations that are known to be associated with resistance to first- and second-line drugs. Furthermore, excluding the need for culture affords new opportunities for biological insights into the evolution of M. tuberculosis antimicrobial resistance and within-patient evolution.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PATHSEEK is funded by the European Union’s Seventh Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no. 304875. Part of this work was funded by the EU FP7 PANNET grant no. 223681.

We acknowledge Edita Pimkina (Vilnius University Hospital Santariskiu Klinikos) for the collection and processing of samples from Lithuania. We are grateful to Poul Liboriussen and Jens Johansen (Qiagen-AAR) for contributions to development of the customized and automated pipeline based on the CLC Genomic Workbench. J. Breuer is supported by the UCL/UCLH and J. Brown by the UCL/GOSH Biomedical resource centers. J. Brown is funded by an NIHR training fellowship. We acknowledge infrastructure support from the UCL MRC Centre for Molecular Medical Virology. We thank all members of the PATHSEEK consortium for their input.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

A. C. Brown, J. Holdstock, D. T. Houniet, J. Z. M. Chan, M. B. McAndrew, and G. Speight are or were employed by Oxford Gene Technology and have received salary and funding from that company, and K. Einer-Jensen is employed by Qiagen-AAR and receives salary and funding from that company.

The manuscript was written by J. M. Bryant, A. C. Brown, and J. Breuer with input from all authors. Bioinformatic analysis and pipeline development were carried out by J. M. Bryant, J. Holdstock, D. T. Houniet, A. C. Brown, J. Z. M. Chan, and K. Einer-Jensen. Samples were supplied and processed by F. Drobniewski, C. Rosmarin, M. Melzer, T. D. McHugh, V. Nikolayevskyy, A. Broda, R. J. Shorten, M. J. Stone, H. Tutill, and J. Brown. Enrichment and sequencing were carried out by A. C. Brown and J. Z. M. Chan. A. C. Brown, D. P. Depledge, and M. T. Christiansen and members of the PATHSEEK Consortium contributed to protocol optimization. The study was coordinated by R. Williams. The study was conceived and initiated by the PATHSEEK Consortium Study Group and managed by J. Breuer, M. B. McAndrew, and G. Speight.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00486-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gandhi NR, Nunn P, Dheda K, Schaaf HS, Zignol M, van Soolingen D, Jensen P, Bayona J. 2010. Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: a threat to global control of tuberculosis. Lancet 375:1830–1843. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weyer K, Mirzayev F, Migliori GB, Van Gemert W, D'Ambrosio L, Zignol M, Floyd K, Centis R, Cirillo DM, Tortoli E, Gilpin C, de Dieu Iragena J, Falzon D, Raviglione M. 2013. Rapid molecular TB diagnosis: evidence, policy making and global implementation of Xpert MTB/RIF. Eur Respir J 42:252–271. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00157212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drobniewski F, Nikolayevskyy V, Maxeiner H, Balabanova Y, Casali N, Kontsevaya I, Ignatyeva O. 2013. Rapid diagnostics of tuberculosis and drug resistance in the industrialized world: clinical and public health benefits and barriers to implementation. BMC Med 11:190. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casali N, Nikolayevskyy V, Balabanova Y, Harris SR, Ignatyeva O, Kontsevaya I, Corander J, Bryant J, Parkhill J, Nejentsev S, Horstmann RD, Brown T, Drobniewski F. 2014. Evolution and transmission of drug-resistant tuberculosis in a Russian population. Nat Genet 46:279–286. doi: 10.1038/ng.2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comas I, Homolka S, Niemann S, Gagneux S. 2009. Genotyping of genetically monomorphic bacteria: DNA sequencing in Mycobacterium tuberculosis highlights the limitations of current methodologies. PLoS One 4:e7815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardy JL, Johnston JC, Ho Sui SJ, Cook VJ, Shah L, Brodkin E, Rempel S, Moore R, Zhao Y, Holt R, Varhol R, Birol I, Lem M, Sharma MK, Elwood K, Jones SJ, Brinkman FS, Brunham RC, Tang P. 2011. Whole-genome sequencing and social-network analysis of a tuberculosis outbreak. N Engl J Med 364:730–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker TM, Ip CL, Harrell RH, Evans JT, Kapatai G, Dedicoat MJ, Eyre DW, Wilson DJ, Hawkey PM, Crook DW, Parkhill J, Harris D, Walker AS, Bowden R, Monk P, Smith EG, Peto TE. 2013. Whole-genome sequencing to delineate Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreaks: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 13:137–146. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70277-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roetzer A, Diel R, Kohl TA, Ruckert C, Nubel U, Blom J, Wirth T, Jaenicke S, Schuback S, Rusch-Gerdes S, Supply P, Kalinowski J, Niemann S. 2013. Whole genome sequencing versus traditional genotyping for investigation of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreak: a longitudinal molecular epidemiological study. PLoS Med 10:e1001387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smit PW, Vasankari T, Aaltonen H, Haanperä M, Casali N, Marttila H, Marttila J, Ojanen P, Ruohola A, Ruutu P, Drobniewski F, Lyytikäinen O, Soini H. 2015. Enhanced tuberculosis outbreak investigation using whole genome sequencing and IGRA. Eur Respir J 45:276–279. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00125914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Köser CU, Bryant JM, Becq J, Torok ME, Ellington MJ, Marti-Renom MA, Carmichael AJ, Parkhill J, Smith GP, Peacock SJ. 2013. Whole-genome sequencing for rapid susceptibility testing of M. tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 369:290–292. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1215305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fadzilah MN, Ng KP, Ngeow YF. 2009. The manual MGIT system for the detection of M. tuberculosis in respiratory specimens: an experience in the University Malaya Medical Centre. Malays J Pathol 31:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chihota VN, Grant AD, Fielding K, Ndibongo B, van Zyl A, Muirhead D, Churchyard GJ. 2010. Liquid vs. solid culture for tuberculosis: performance and cost in a resource-constrained setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 14:1024–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warren RM, Victor TC, Streicher EM, Richardson M, Beyers N, Gey van Pittius NC, van Helden PD. 2004. Patients with active tuberculosis often have different strains in the same sputum specimen. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 169:610–614. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200305-714OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krüüner A, Yates MD, Drobniewski FA. 2006. Evaluation of MGIT 960-based antimicrobial testing and determination of critical concentrations of first- and second-line antimicrobial drugs with drug-resistant clinical strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 44:811–818. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.811-818.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamerbeek J, Schouls L, Kolk A, van Agterveld M, van Soolingen D, Kuijper S, Bunschoten A, Molhuizen H, Shaw R, Goyal M, van Embden J. 1997. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol 35:907–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE III, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, Wilson RK. 2012. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res 22:568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stamatakis A. 2006. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryant JM, Schurch AC, van Deutekom H, Harris SR, de Beer JL, de Jager V, Kremer K, van Hijum SA, Siezen RJ, Borgdorff M, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, van Soolingen D. 2013. Inferring patient to patient transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from whole genome sequencing data. BMC Infect Dis 13:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plinke C, Walter K, Aly S, Ehlers S, Niemann S. 2011. Mycobacterium tuberculosis embB codon 306 mutations confer moderately increased resistance to ethambutol in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:2891–2896. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00007-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sreevatsan S, Stockbauer KE, Pan X, Kreiswirth BN, Moghazeh SL, Jacobs WR Jr, Telenti A, Musser JM. 1997. Ethambutol resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: critical role of embB mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:1677–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakuła Z, Napiórkowska A, Bielecki J, Augustynowicz-Kopeć E, Zwolska Z, Jagielski T. 2013. Mutations in the embB gene and their association with ethambutol resistance in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates from Poland. Biomed Res Int 2013:167954. doi: 10.1155/2013/167954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safi H, Fleischmann RD, Peterson SN, Jones MB, Jarrahi B, Alland D. 2010. Allelic exchange and mutant selection demonstrate that common clinical embCAB gene mutations only modestly increase resistance to ethambutol in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:103–108. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01288-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hazbón MH, Brimacombe M, Bobadilla del Valle M, Cavatore M, Guerrero MI, Varma-Basil M, Billman-Jacobe H, Lavender C, Fyfe J, García-García L, León CI, Bose M, Chaves F, Murray M, Eisenach KD, Sifuentes-Osornio J, Cave MD, Ponce de León A, Alland D. 2006. Population genetics study of isoniazid resistance mutations and evolution of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2640–2649. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00112-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavusoglu C, Karaca-Derici Y, Bilgic A. 2004. In-vitro activity of rifabutin against rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates with known rpoB mutations. Clin Microbiol Infect 10:662–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson MC, Morrison HG, Benjamino J, Grim SL, Graf J. 2014. Analysis, optimization and verification of Illumina-generated 16S rRNA gene amplicon surveys. PLoS One 9:e94249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Achtman M. 2008. Evolution, population structure, and phylogeography of genetically monomorphic bacterial pathogens. Annu Rev Microbiol 62:53–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Moamary MS, Black W, Bessuille E, Elwood RK, Vedal S. 1999. The significance of the persistent presence of acid-fast bacilli in sputum smears in pulmonary tuberculosis. Chest 116:726–731. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.3.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Zhao B, Huang H, Zhu Y, Peng J, Dai G, Jiang G, Liu L, Zhao Y, Jin Q. 2013. Co-occurrence of amikacin-resistant and -susceptible Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in clinical samples from Beijing, China. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1537–1542. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolani MP, D'souza DT, Mistry NF. 2012. Drug resistance mutations and heteroresistance detected using the GenoType MTBDRplus assay and their implication for treatment outcomes in patients from Mumbai, India. BMC Infect Dis 12:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cullen MM, Sam NE, Kanduma EG, McHugh TD, Gillespie SH. 2006. Direct detection of heteroresistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis using molecular techniques. J Med Microbiol 55:1157–1158. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falagas ME, Makris GC, Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK. 2008. Heteroresistance: a concern of increasing clinical significance? Clin Microbiol Infect 14:101–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doughty EL, Sergeant MJ, Adetifa I, Antonio M, Pallen MJ. 2014. Culture-independent detection and characterisation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. africanum in sputum samples using shotgun metagenomics on a benchtop sequencer. PeerJ 2:e585. doi: 10.7717/peerj.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.