Abstract

Tibetans do not exhibit increased hemoglobin concentration at high altitude. We describe a high-frequency missense mutation in the EGLN1 gene, which encodes prolyl hydroxylase 2 (PHD2), that contributes to this adaptive response. We show that a variant in EGLN1, c.[12C>G; 380G>C], contributes functionally to the Tibetan high-altitude phenotype. PHD2 triggers the degradation of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), which mediate many physiological responses to hypoxia, including erythropoiesis. The PHD2 p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] variant exhibits a lower Km value for oxygen, suggesting that it promotes increased HIF degradation under hypoxic conditions. Whereas hypoxia stimulates the proliferation of wild-type erythroid progenitors, the proliferation of progenitors with the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] mutation in EGLN1 is significantly impaired under hypoxic culture conditions. We show that the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] mutation originated ~8,000 years ago on the same haplotype previously associated with adaptation to high altitude. The c.[12C>G; 380G>C] mutation abrogates hypoxia-induced and HIF-mediated augmentation of erythropoiesis, which provides a molecular mechanism for the observed protection of Tibetans from polycythemia at high altitude.

High-altitude populations have developed genetic adaptations that permit their survival in extremely hypoxic environments. In most non-adapted individuals, exposure to high-altitude hypoxia leads to an elevation of hematocrit levels and an increased number of erythrocytes (polycythemia). In contrast, the majority of Tibetan highlanders maintain hematocrit levels comparable to those for populations living at sea level1. Although increased hemoglobin concentration might be considered to be a beneficial adaptation to hypoxia, excessive erythrocytosis results in high blood viscosity, which impairs tissue blood flow and oxygen delivery2,3. Several studies have reported evidence for positive natural selection at the EGLN1 and EPAS1 loci, both of which are associated with the HIF pathway4–6. EGLN1 encodes HIF prolyl 4-hydroxylase 2 (PHD2), and EPAS1 encodes the HIF-2α subunit. Mutations or dysregulation of these genes or their products has been reported to be associated with anemia and polycythemia2,3. In addition, variation at the EGLN1 locus is associated with protection against polycythemia in Tibetan highlanders4,7,8, and SNPs at the EPAS1 locus are associated with hemoglobin levels in Tibetans5,6.

HIFs are transcription factors that function as master regulators of oxygen homeostasis. They are composed of a hypoxia-inducible α subunit and a constitutively expressed β subunit. The α subunit has three different isoforms; HIF-1α, HIF-2α (encoded by EPAS1) and HIF-3α (refs. 8–10). The HIF-1α subunit is ubiquitously expressed, whereas HIF-2α and HIF-3α have tissue-specific patterns of expression. HIF-1 was discovered as a result of studies on erythropoietin (EPO)11, the key hormone that stimulates erythroid progenitors and regulates the production of erythrocytes; however, it was later found that EPO production is primarily regulated by HIF-2α (refs. 12,13). In the presence of oxygen, HIF α subunits are hydroxylated by PHD2, which generates a binding site for the von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) protein and results in their polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation10. Thus, PHD2 and VHL are the major oxygen-dependent negative regulators of HIFs. HIFs can also augment erythropoiesis by EPO-independent mechanism(s) that are yet to be elucidated13,14 and can regulate the uptake of iron that is required for hemoglobin synthesis13.

We report a missense variant of the EGLN1 gene, c.12C>G, that is in almost complete linkage disequilibrium (LD) with a previously reported missense variant in this gene, c.380G>C. Both c.12C>G and c.380G>C are observed almost exclusively on a haplotype we previously identified as a strong candidate for conferring Tibetan high-altitude adaptation on the basis of tests of extended haplotype homozygosity (iHS and XPEHH) and association with protection from polycythemia4. Kinetic studies of recombinant p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 and functional assessment of native erythroid progenitors homozygous for the variant encoding p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 demonstrate that the variant protein has increased hydroxylase activity under hypoxic conditions. We demonstrate that this variant contributes to the molecular and cellular basis of Tibetan adaptation to high altitude by blunting the erythropoietic response to hypoxia.

RESULTS

Genomic screening for adaptive mutations in Tibetans

We first screened for sequence variants in candidate genes. Twenty-six Tibetans living in Virginia and Utah (designated hereafter as US Tibetans) were recruited for our studies. The ancestral composition of the local Tibetans is depicted in Table 1, and that of 121 Asian (Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Mongolian and Filipino) and European control subjects is shown in Supplementary Table 1. In earlier studies, variant alleles of EGLN1 (NCBI RefSeq NG_015865), EPAS1 (NCBI RefSeq NG_016000) and PPARA (NCBI RefSeq NG_012204) were significantly associated with lower hemoglobin concentrations in Tibetan highlanders4–6. Genomic DNA sequencing of the exons, exon-intron boundaries and promoter region of PPARA15 did not identify any sequence variants in four Tibetans. No sequence variants in EPAS1 were identified in the 16 exons and exon-intron boundaries of genomic DNA from 2 Tibetans with the EPAS1 haplotype previously reported to be under positive selection. Initially, exon sequencing of EGLN1 in Tibetan genomic DNA identified 2 missense mutations in cis in exon 1: 22 genomic DNA samples had a new c.12C>G variant (NM_022051), and all 26 samples (at the time of the original evaluation)7 had a known but unvalidated SNP, rs12097901 (c.380G>C; NM_022051). The minor allele frequency for the c.380G>C variant was reported to be 20% in the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 1 sample in 2011.

Table 1.

Genotyping results for EGLN1 exon 1 mutations in 26 Us tibetans

| Sample | Sex | Age (years) | Region | p.Asp4Glu | p.Cys127Ser |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TU01 | F | 35 | U-Tsang | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU02 | F | 36 | Mixed | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU03 | M | 31 | Kham | Heterozygous | Heterozygous |

| TU04 | M | 61 | Mixed | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU05 | M | 44 | Kham | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU06 | M | 34 | U-Tsang | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU07 | M | 38 | U-Tsang | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU08 | M | ND | U-Tsang | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU09 | M | ND | Mixed | Wild type | Heterozygous |

| TU10 | F | ND | Mixed | Heterozygous | Heterozygous |

| TU11 | F | 46 | Kham | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU12 | M | 46 | Mixed | Wild type | Heterozygous |

| TU13 | M | 46 | Mixed | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU14 | M | 38 | Kham | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU15 | M | 53 | Kham | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU16 | F | 24 | U-Tsang | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU17 | M | 30 | Kham | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU18 | M | 36 | U-Tsang | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU19 | F | 43 | U-Tsang | Wild type | Homozygous |

| TU20 | M | 39 | U-Tsang | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU21 | M | 41 | Kham | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU22 | M | 40 | U-Tsang | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU23 | F | 41 | U-Tsang | Wild type | Heterozygous |

| TU24 | M | 41 | Kham | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU25 | F | 36 | U-Tsang | Homozygous | Homozygous |

| TU26 | F | 38 | U-Tsang | Homozygous | Homozygous |

Individuals of Tibetan ancestry are generally divided into three known major subgroups: U-Tsang, Kham and Amdo. M, male; F, female; ND, no data.

Frequency of the EGLN1 variants

We then determined the frequency of the c.12C>G and c.380G>C EGLN1 alleles in Tibetans and non-Tibetans (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). The c.380G>C variant was found in all 26 US Tibetan DNA samples and occurred in non-Tibetan controls at a frequency of ~20%, which is consistent with the 1000 Genomes Project estimate. By comparison, the frequency of the c.12C>G variant was 85% in local Tibetans (20 homozygotes, 2 heterozygotes and 4 wild type) but only 0.8% in 242 non-Tibetans (occurring in 1 Mongolian subject and 1 Japanese subject, both of whom were heterozygous). This variant was submitted to the NCBI dbSNP database as ss538786686/rs186996510. More recently, we studied an additional 26 Tibetans living in Himachal Pradesh in northern India. We also collaborated with the Research Center for High-Altitude Medicine of Qinghai University in China, and the following subjects living on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau agreed to participate in our studies: 13 subjects from the provincial capital of Xining and 26 subjects from Huashixia township (Zorgenrawa in Tibetan), Madoi county in Qinghai province. In subjects from these expanded Tibetan cohorts (n = 65) and US Tibetans (n = 26), the frequency of the c.12C>G variant was 88% (n = 91; 46 homozygotes, 34 heterozygotes and 11 wild type; Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). With the exception of one apparent intragenic crossover (Supplementary Table 2, subject MG08), the c.12C>G allele was always observed on a haplotype containing the c.380G>C allele. Although we are not able to determine the level of population structure and/or admixture in each Tibetan cohort examined, we suspect that these factors underlie the differences observed between local and other Tibetans with respect to the frequency of c.12C>G homozygosity. Our recent analyses of regional Tibetan populations identify clustering of geographically separate groups within Tibet in addition to distinct differences in the amount of genetic admixture16.

Positive selection of the EGLN1 variants

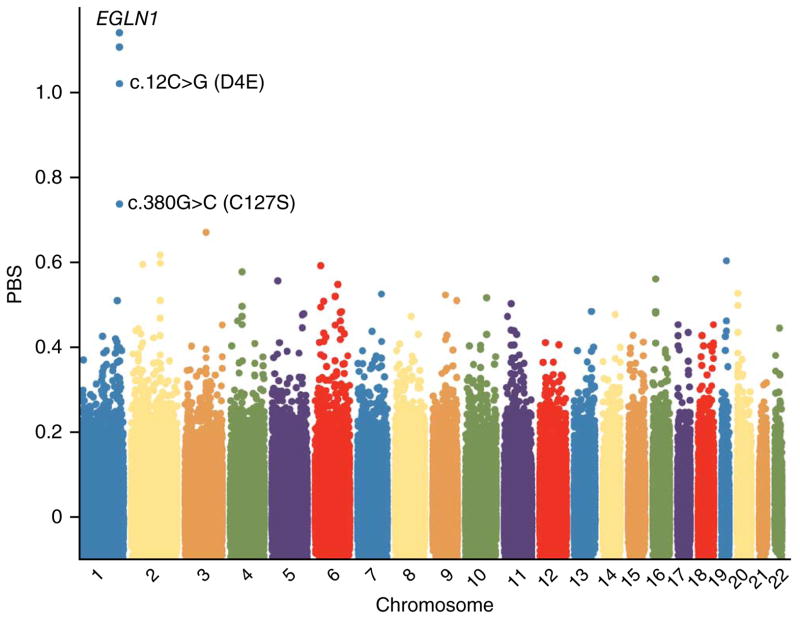

To search for genomic evidence of positive selection for the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] compound allele of EGLN1, we genotyped >900,000 SNPs in 17 US Tibetan samples using the Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix). We identified two pairs of Tibetans as close relatives (TU02 and TU04; TU05 and TU08) and excluded one of the related individuals from each pair from all subsequent analyses (Online Methods). Principal-components and ADMIXTURE analyses indicated that the ancestries of the current Tibetan samples were similar to those of the Tibetan population in which the selection signal at the EGLN1 locus was identified (Supplementary Fig. 1). Next, we estimated the population branch statistic (PBS), which compares pairwise estimates of population differentiation (FST) among three populations to detect sites that are highly divergent in the population of interest6. When comparing Europeans, Mongolians and Tibetans, the PBS for the c.12C>G variant of EGLN1 was 1.02, which was the fifth most extreme value that we observed (empirical P value = 9 × 10−6) (Fig. 1). The four SNPs with more extreme PBS values (rs12063614, rs12563076, rs11122250 and rs6541261) were also located at the EGLN1 locus (Fig. 1) but did not cause amino acid changes in PHD2. Using population-based phasing on 16 US Tibetans, we estimated that the major allele for each of these 4 SNPs was present on 25 of the 26 chromosome copies (of a total of 32) that carried the c.12C>G variant. Thus, the elevated PBS values of these SNPs are likely the result of genetic hitchhiking with the c.12C>G mutation.

Figure 1.

Genome-wide allele frequency differentiation between Tibetans, Mongolians and Europeans. To measure genome-wide differentiation in allele frequency between Tibetans and Mongolians, we calculated the PBS for the c.12C>G and c.380G>C variants in EGLN1 for each Affymetrix SNP. We included all unrelated Tibetan, Mongolian and European individuals in the analysis for whom we had Affymetrix 6.0, c.12C>G and c.380G>C genotype data. The final set included 16 Tibetans, 11 Mongolians and 14 Europeans. The PBS for c.12C>G was 1.02 (empirical P value = 9 × 10−6). The four SNPs with PBS greater than 1.02 were all located in the EGLN1 region.

Age of the EGLN1 variant

On the basis of high-density SNP data from 16 unrelated US Tibetans, we estimated the age of the c.12C>G mutation in EGLN1 by measuring the decay of LD surrounding the mutation using a previously described approach17. The maximum-likelihood estimate for the age of the c.12C>G mutation was 8,000 years, on the basis of a 25-year generation time (95% confidence interval (CI) = 5,100–11,900 years; Supplementary Table 4). Because the c.380G>C allele was present at intermediate frequency in several non-Tibetan populations, the more recent c.12C>G mutation probably arose on a chromosome that contained the c.380G>C mutation. The relatively young estimated age and high frequency of this Tibetan-specific variant are consistent with a rapid increase in allele frequency due to strong positive natural selection.

Kinetic analyses and in cellulo experiments

To characterize the functional properties of the selected Tibetan p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 double mutant and the p.Asp4Glu and p.Cys127Ser single mutants in the context of high-altitude adaptation, we performed kinetic analyses of recombinant proteins under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. The p.Asp4Glu and p.Cys127Ser single-mutant and p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] double-mutant enzymes were expressed as recombinant proteins in insect cells and were affinity purified. The mutant enzymes migrated similarly to wild-type PHD2 on SDS-PAGE and showed no signs of degradation (Supplementary Fig. 2). The Km and Vmax values for DLD19, a 19-residue synthetic peptide encompassing the HIF-1α C-terminal hydroxylation site, were identical in all mutants to the values for the wild-type enzyme (Table 2). The Km value was also assessed for a more natural substrate, the HIF-2α O2-dependent degradation domain (ODDD), a 250-aminoacid recombinant polypeptide encompassing both the N- and C-terminal prolyl hydroxylation sites of HIF-2α. For p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2, the Km was 100 nM, which is slightly higher than the 70 nM seen for wild-type PHD2 (P < 0.05; Table 2). However, the Vmax of p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 for the HIF-2α ODDD was 30% greater than that for wild-type PHD2 (P < 0.005; Table 2), most likely reflecting compensation for a possible minor difference in hydroxylation due to the slightly higher Km value of the mutant.

Table 2.

Kinetic values for the PHD2 p.Asp4Glu and p.cys127ser mutants

| Enzyme | DLD19

|

HIF-2α ODDD

|

2-oxoglutarate

|

O2

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (μM) | Vmax (%) | n | Km (nM) | Vmax (%) | n | Km (μM) | Vmax (%) | n | Km (μM) | Vmax (%) | n | |

| Wild-type PHD2 | 13 ± 3 | 100 | 3 | 70 ± 20 | 100 | 5 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 100 | 4 | 150 ± 50 | 100 | 8 |

| p.Asp4Glu PHD2 | 11 ± 2 | 90 | 3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 150 ± 30 | 100 | 4 | ||

| p.Cys127Ser PHD2 | 14 ± 3 | 105 | 3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 160 ± 50 | 110 | 4 | ||

| p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 | 14 ± 1 | 100 | 3 | 100 ± 40* | 130** | 5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 80 | 4 | 110 ± 30* | 100 | 8 |

Values are mean ± s.d. Vmax values are expressed relative to the Vmax value obtained for wild-type PHD2.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.005, Student’s two-tailed t test. n is the number of assays conducted. ND, not determined.

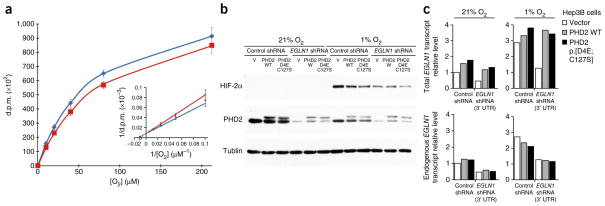

Next, we performed kinetic analyses of the two other cosubstrates of PHD2, 2-oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) and oxygen18. The Km and Vmax values of p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 for 2-oxoglutarate were determined using DLD19 as a substrate and were identical to those for the wild-type enzyme (Table 2). The Km and Vmax values of the p.Asp4Glu and p.Cys127Ser PHD2 single mutants for O2 were determined using the HIF-2α ODDD as a substrate and were identical to those of the wild-type enzyme (Table 2). However, the Km value of p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 for O2 was 110 μM, which is ~30% lower than the value of 150 μM for wild-type PHD2 (P < 0.05; Fig. 2a and Table 2), whereas the Vmax value was identical to that for the wild-type enzyme (Table 2). The Km values of the p.Asp4Glu and p.Cys127Ser single mutants for O2 were also significantly higher than that for the p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] double mutant (P = 0.05 and P < 0.05, respectively; Table 2), suggesting an epistatic interaction between the two mutations. Thus, the p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] protein is capable of more efficiently hydroxylating HIF α subunits at lower oxygen tensions than wild-type PHD2.

Figure 2.

The p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 mutant shows gain of function under hypoxia. (a) The Km value for O2 for the p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 mutant is lower than that for wild-type PHD2. Shown is the effect of O2 concentration on the reaction velocity of wild-type PHD2 (red line) and the p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] mutant (blue line), using the HIF-2α ODDD as a substrate. The inset shows the corresponding double-reciprocal plot. The data presented are the average ± s.e.m. of eight independent assays comparing wild-type PHD2 and the p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] mutant in the same assay. Data from independent assays were normalized relative to the disintegrations per minute (d.p.m.) obtained with wild-type PHD2 at an O2 concentration of 212 μM. (b) Decreased HIF-2α accumulation in hypoxic cells expressing p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 in knockdown-rescue experiments. Shown is a representative immunoblot analysis of Hep3B cells expressing Venus fluorescent protein (V), wild-type (WT) PHD2 or p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2. Cells were stably coinfected with an shRNA targeting the 3′ UTR of endogenous EGLN1 (not present in the rescue constructs) or a negative control shRNA and were grown in the presence of 21% or 1% O2 for 12 h. Decreased HIF-2α levels in cells expressing the p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] variant were observed in three independent experiments. The electrophoretic mobility of the exogenous PHD2 protein was slightly decreased owing to the presence of the Flag epitope. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (c) RT-PCR demonstrates knockdown of endogenous EGLN1 in Hep3B cells by the EGLN1-targeted shRNA and equal levels of transgene transcripts in cells expressing the transgenes for wild-type and p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2. Shown are representative data from three independent experiments.

We then asked whether the lower Km of the p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] variant for oxygen resulted in alterations in HIF-2α stabilization. Hep3B hepatoma cells were infected with a lentivirus expressing a Venus fluorescent protein as a negative control, wild-type PHD2 or the PHD2 p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] variant. To directly compare wild-type PHD2 and the p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] mutant, endogenous PHD2 was knocked down using a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting the 3′ UTR of EGLN1, which was lacking in the cDNAs used to express exogenous PHD2. After antibiotic selection for stably transduced cells, we cultured the cells in 21% or 1% O2 for 12 h and quantified HIF-2α levels by protein blotting. Cells expressing the p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] variant had decreased HIF-2α protein levels under hypoxic conditions when compared to cells expressing wild-type PHD2 (Fig. 2b). A similar trend was noted for HIF-1α, but the effect was less consistent. Knockdown of endogenous EGLN1 and equal transgene expression were confirmed to rule out differences due to dissimilar PHD2 expression levels (Fig. 2c). These data suggest that the p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] variant is more active in downregulating HIF α subunits under hypoxic conditions.

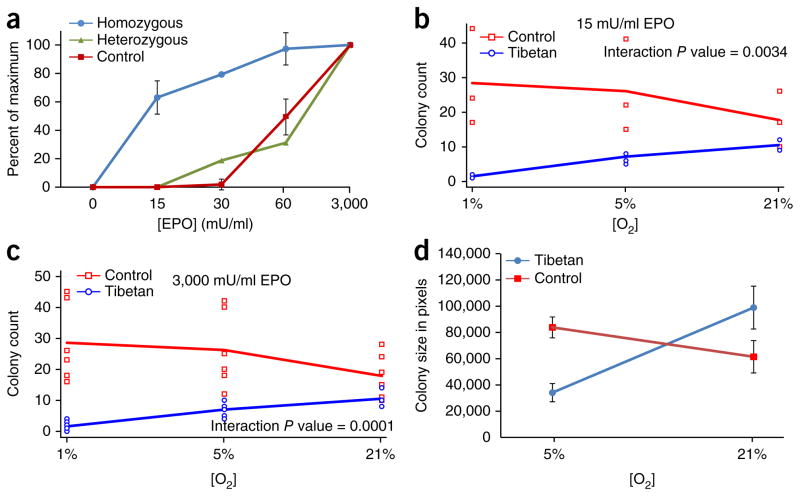

In vitro analysis of erythropoiesis by BFU-E assay

HIFs directly stimulate erythropoiesis3,19, in addition to and independently of the augmentation of circulating EPO. Peripheral blood contains early erythroid progenitors, which form erythroid colonies in vitro (burst-forming units–erythroid, BFU-Es) when cultured in methylcellulose in the presence of EPO. BFU-Es were isolated from the peripheral blood of three US Tibetans and ten control subjects. Progenitors from two Tibetans who were homozygous for the variant encoding p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 were hypersensitive to EPO in comparison to progenitors from the ten controls, whereas progenitor cells from the US Tibetan who was heterozygous for the variant encoding p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 had decreased EPO sensitivity in comparison to BFU-Es homozygous for the variant encoding p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] PHD2 (Fig. 3a). Hypersensitivity to EPO is a feature found in inherited disorders associated with increased HIF activity3,19. Indeed, HIF-regulated gene expression was increased in normoxic cultures of erythroid colonies from Tibetans homozygous for the variant encoding p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, analysis of erythropoiesis at ambient oxygen concentration does not reflect physiological hypoxia in the bone marrow, which is further accentuated by hypoxia at high altitudes. Thus, erythropoiesis was then reevaluated in vitro in a controlled hypoxic environment.

Figure 3.

Erythroid colony (BFU-E) assays. Erythroid colonies were enumerated after stimulation with various concentrations of EPO. (a) BFU-Es homozygous for the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] variant in EGLN1 are hypersensitive to EPO under normoxia. BFU-E colony assays in Tibetans homozygous (n = 2 biological replicates) or heterozygous (n = 1) for the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] variant in comparison to normal controls (n = 10) at different EPO concentrations. Values are normalized to the number of BFU-Es grown at ambient oxygen tension at 3,000 mU/ml EPO, which was expressed as 100%. Designated error bars in controls and for cells homozygous for c.[12C>G; 380G>C] represent ±s.d. (b) Sensitivity of BFU-Es to low EPO concentration (15 mU/ml). Hypersensitive BFU-Es from Tibetans with the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] variant (n = 6) lose their hypersensitivity to EPO as the oxygen tension decreases to 5% and fail to form colonies at 1% O2, whereas control colonies (n = 3) become hypersensitive to EPO with increasing hypoxia. (c) Colony growth of progenitor cells from a Tibetan with the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] mutation and controls at 3,000 mU/ml EPO. Tibetan BFU-E colonies with the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] mutation have decreased colony formation with ambient O2 levels and 5% O2, and they fail to grow at 1% O2. In contrast, BFU-Es from control subjects (n = 3) form more colonies as the oxygen tension decreases. (d) Size of erythroid colonies increases in BFU-Es from controls but decreases for progenitor cells from a Tibetan with the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] mutation. Average BFU-E colony size represented in pixels (y axis) is greater in BFU-E colonies from the control subject under hypoxia (5% O2), whereas, in the Tibetan subject with the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] mutation, hypoxia decreases BFU-E colony size. Error bars in Tibetans and controls represent ±s.d. (Fig. 3a is an independent experiment performed with different individuals and at a different time than the experiments in Fig. 3b–d, which consist of 6 biological replicates (5 Tibetans homozygous and 1 Tibetan heterozygous for c.[12C>G; 380G>C]) together with 3 controls.)

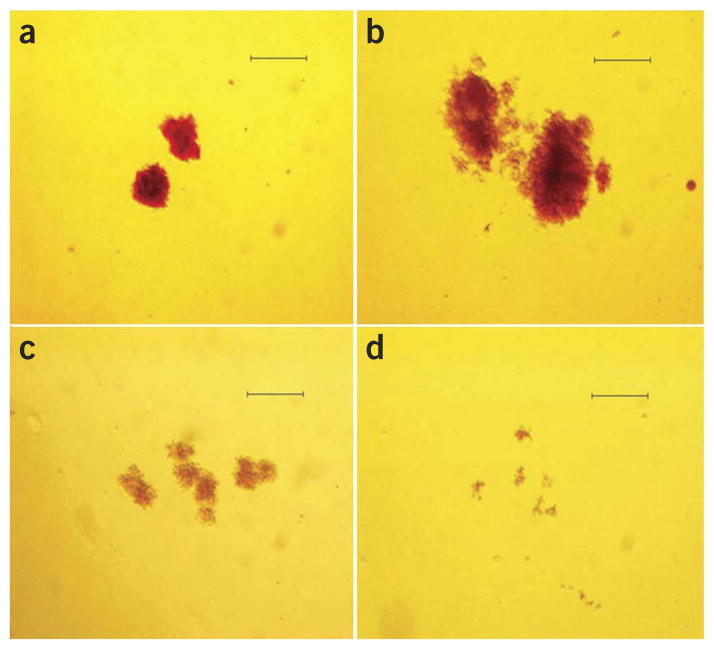

Normal erythroid progenitors had exaggerated growth, increased hemoglobinization and increased sensitivity to EPO when incubated under hypoxic conditions (1% or 5% O2; Fig. 3b–d), as previously reported20,21. However, concomitantly tested erythroid progenitors from six Tibetans (five subjects homozygous for the variant encoding p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] and one subject heterozygous for the variant encoding p.Asp4Glu; cells homozygous for the variant encoding p.Cys127Ser did not grow at all at 1% O2 (Fig. 4) and, at 5% O2, their proliferation and hypersensitivity to EPO were decreased (Fig. 3b,c). Additionally, the mean size of the BFU-Es from controls increased under hypoxic conditions, whereas the mean size (P = 0.0017) and hemoglobinization of the BFU-Es from homozygotes for the variant encoding p.[Asp4Glu; Cys127Ser] were decreased (Figs. 3d and 4).

Figure 4.

Hypoxia increases the proliferation of control BFU-E colonies but decreases that of colonies with the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] mutation in EGLN1. BFU-Es were grown in 3,000 mU/ml EPO, and all images were acquired at 40× magnification (scale bars, 1 mm). (a,b) Representative colonies from a control (wild type) subject and (c,d) a Tibetan subject homozygous for the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] mutation. Note the larger colony sizes for the control BFU-E colonies under hypoxia (5% O2) (b) relative to ambient oxygen tension (a). BFU-Es with the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] mutation exhibit smaller colony sizes under normoxia (c) in comparison to control cells (a), and the colonies are paler than the controls, reflecting the decreased hemoglobinization with the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] erythroid progenitors in comparison to the controls. (d) The decrease in colony size and hemoglobinization for Tibetan BFU-Es with the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] mutation is even more pronounced under 5% O2 (in comparison to b).

DISCUSSION

We report a new missense mutation in EGLN1, c.12C>G, that coexists in cis in c.[12C>G; 380G>C] with the previously reported c.380G>C EGLN1 variant and is present in the majority of Tibetans (SNP ss538786686/rs186996510)7. The c.12C>G mutation originated ~8,000 years ago, most likely on a haplotype with the c.380G>C mutation. The c.12C>G variant was not reported in an analysis of 50 Tibetan exomes6, likely owing to the high GC content in this region. Similarly, this region of exon 1 of EGLN1 could not be successfully sequenced in 54 high-coverage whole genomes from the Complete Genomics Diversity Panel22. Therefore, this region appears to have particularly poor coverage in next-generation sequence data, which explains why the c.12C>G variant escaped detection in previous studies.

The association of SNPs at the EGLN1 locus with high-altitude adaptation (absence of polycythemia) was reported previously in Tibetans4, as well as in Andeans23, and loss-of-function EGLN1 mutations are associated with dominantly inherited congenital polycythemia24–28. Furthermore, two SNPs in the first intron of EGLN1, rs479200 and rs480902, differ substantially in frequency between samples from highland and lowland populations in India and are associated with increased risk of high-altitude pulmonary edema in the latter29.

The catalytic domain of PHD2 starts at residue 181 and extends through the end of the 426-residue polypeptide. Several missense mutations affecting the catalytic domain and mutations that lead to a truncated protein lacking the catalytic domain have been reported previously to be linked to familial polycythemia22–28. The high-altitude Tibetan variant c.[12C>G; 380G>C] in EGLN1 enhances the catalytic activity of PHD2 under hypoxic conditions; however, it does not affect the catalytic domain. The currently available three-dimensional structure of PHD2 only contains the catalytic domain; therefore, modeling of the p.Asp4Glu and p.Cys127Ser alterations is not feasible. However, our data suggest that the Tibetan c.[12C>G; 380G>C] variant alters oxygen binding and perhaps also HIF-2α substrate binding to PHD2 and, under hypoxia, is a gain-of-function mutation of PHD2, the principal negative regulator of HIFs.

When we demonstrated that the EGLN1 haplotype in Tibetans is associated with protection from polycythemia4, we hypothesized that this haplotype might be associated with an EGLN1 gain-of-function mutation resulting in decreased HIF activity and, possibly, decreased EPO levels and blunted erythropoiesis. However, our initial functional assessment of erythroid progenitors bearing the homozygous haplotype found that, under normoxia, it is associated with augmented rather than decreased erythropoiesis (Fig. 3a). This feature is found in inherited disorders associated with increased HIF levels, as first reported for Chuvash polycythemia, which is caused by a missense mutation in VHL encoding a p.Arg200Trp alteration that reduces binding to hydroxylated HIF α subunits and thus increases HIF-1 and HIF-2 levels30. Missense mutations in EGLN1 (ref. 31) and EPAS1 (ref. 32) interfere with the hydroxylation and degradation of HIF-2α by PHD2 and are also associated with polycythemia in humans. Similarly, a study of erythropoiesis in Hif1a−/− mice demonstrated that HIF-1 stimulates erythropoiesis through a mechanism that is independent of EPO14. The molecular basis for the normoxic augmentation of erythropoiesis that we observed in individuals who express the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] variant remains to be determined and might be explained by co-selected haplotypes at other loci, such as EPAS1.

The erythroid progenitor cells from six Tibetans homozygous for c.[12C>G; 380G>C] in EGLN1 had decreased proliferation, EPO sensitivity, colony size and hemoglobinization when incubated at 5% O2 and did not grow at all at 1% O2. In striking contrast, control erythroid progenitors had exaggerated growth and increased EPO sensitivity, colony size and hemoglobinization under hypoxic conditions (1% or 5% O2; Figs. 3a–d and 4), as previously reported20,21.

Tibetan high-altitude adaptation is not determined by a single gene but by multiple evolved genetic adaptations acting in concert33. These mutations may have different effects on the regulation of erythropoiesis, as well as on metabolism, which is another major target of HIF regulation34. In aggregate, the data we present here support the key role of the c.[12C>G; 380G>C] variant in EGLN1 as a major molecular mechanism by which Tibetans are protected from developing polycythemia at high altitude. Further studies are warranted to determine whether these alleles also alter other pathological responses to high-altitude hypoxia, such as pulmonary hypertension. A more complete understanding of the genetic basis for adaptation to high altitude may lead to new approaches for the treatment of common causes of mortality, such as ischemic cardiovascular disease, in which hypoxia has a major pathophysiological role.

ONLINE METHODS

Subjects

Twenty-six Tibetans residing in Virginia and Utah (referred to as US Tibetans) were recruited for the study. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Utah Regulatory Knowledge and Clinical Research Ethics Committee in the United States, from the Sheri-Kashmir Institute of Medical Science Ethics Committee in India and from the Quinghai University Institutional Ethics Committee in China; informed consent was obtained from all participants. Of the 26 US Tibetans, 11 originate in U-Tsang, 8 originated in Khamba, 1 originated in Amdo and 6 were of mixed Tibetan ancestry; none of the 26 subjects had any known chronic illness or history of smoking. DNA from healthy Salt Lake City volunteers was complemented by anonymous DNA from the Sorensen Molecular Genealogy Foundation (SMGF) and the Baylor College of Medicine Department of Genetics (BCMDG) population database, serving as controls. These controls constituted DNA from 74 European Americans, 14 subjects of mixed Asian ancestry (Korean, Japanese and Filipino) from Salt Lake City, 11 anonymous Mongolians4,35, 6 Japanese and 16 Han Chinese (SMGF and BCMDG). Additional information on subject recruitment is given in the Supplementary Note.

Sample preparation

Peripheral blood was collected using acid citrate buffer (ACD) tubes, and plasma, mononuclear cells, granulocytes and platelets were separated and archived for future use with the Histopaque density gradient method (Sigma-Aldrich). Nucleic acids were extracted from granulocytes and mononuclear cells using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center), and, for some samples only, genomic DNA was isolated using the PureGene DNA purification kit (Qiagen). Mononuclear cells from subjects were used for evaluation of the sensitivity of erythroid progenitors to EPO (BFU-E assays; see below), and five BFU-E colonies were pooled from each individual separately and used for RNA isolation.

Genomic analyses

In general, for the initial screening of the PPARA and EGLN1 genes, four representative samples were used and two representative samples were used for EPAS1. The sequences for the promoter region of the PPARA gene15 and the exons and intron-exon boundaries of the PPARA, EPAS1 and EGLN1 genes were obtained from NCBI GenBank via the NCBI website; the corresponding sequences were amplified using the primers and conditions listed in Supplementary Table 5 and were sequenced in both directions. PCR was carried out using Phusion High-Fidelity Master Mix (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol.

Analysis of EGLN1 exon 1

Exon 1 of EGLN1 spans 4,047 bp, and the distal 891-nt region encodes the N terminus of the PHD2 protein. This region of exon 1 is GC rich (70%) with multiple repeats, and amplification was performed using forward primers flanking the coding region of exon 1 (Supplementary Table 5) with PreMix G from the FailSafe PCR System (Epicentre). The 1,025-bp amplicon generated by PCR was then purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen) and sequenced in both directions.

SNP genotyping

We genotyped 16 local Tibetans using the Affymetrix 6.0 SNP array (>900,000 SNPs) and performed genotype calling using the Affymetrix Genotyping Console 3.1 (Affymetrix). The genotypes used for analyses included all autosomes (no sex chromosomes or mitochondrial DNA). We augmented these samples with the HapMap CHB and JPT (Chinese and Japanese) populations (International HapMap Consortium, 2007) and with 31 Tibetan individuals and 25 Buryat Mongolian individuals who we previously genotyped4,35. The sample of 25 Mongolian individuals included the 11 individuals genotyped for the c.12C>G and c.380G>C variants in EGLN1. We performed principal-components and AMIXTURE analyses (Supplementary Fig. 1) as previously described36, excluding related individuals. Using the tool Estimation of Recent Shared Ancestry (ERSA)37, we determined that 2 of the 18 local Tibetans were close relatives and excluded 1 of the related individuals from all subsequent analyses. We calculated PBS in the 16 local Tibetans and 11 Mongolians and 14 Europeans for c.12C>G and c.380G>C in EGLN1 and for all Affymetrix SNPs with a call rate of at least 95% in each sample. We used the Beagle software package38 to estimate phase in the 16 local Tibetans. We then estimated the age of the c.12C>G mutation from the decay of LD in the local Tibetans, according to the methods described17,39.

Reverse-transcription and real-time PCR

A portion (1 μg) of RNA was treated with DNase I to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. The integrity of the RNA was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and by an optical density at 260/280 nm of 2.0 ± 0.2 as measure by NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA was then reverse transcribed using SuperScript VILO (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Hydrolysis probes were acquired from Applied Biosystems (Life Technologies) and are listed in Supplementary Table 5. The amount of each target mRNA was normalized using HPRT1 and GAPDH mRNA for granulocytes, whereas RPLP0 and TFRC mRNA were used for normalization of the erythroid progenitor colonies, on the basis of the eight reference genes used to validate normalization for blood and erythroid progenitors in using geNorm Plus (Biogazelle) (data not shown). Amplification reactions were carried out using the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) with 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s followed by 60 °C for 1 min. To assess reaction specificity, analyses were also carried out without reverse transcriptase or template, with both serving as negative controls.

Quantitative RT-PCR data and statistical analysis

The Livak method with REST 2009 software (Qiagen) was employed to analyze the generated data set using at least two reference genes. The data presented represent the mean and s.d. of at least two separate experiments performed in duplicate. Differences between control and Tibetan samples were analyzed using the Student’s t test, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Expression, purification and kinetic analyses of p.Asp4Glu, p.Cys127Ser and p.[Asp4Glu;Cys127Ser] PHD2

The mutations encoding p.Asp4Glu and p.Cys127Ser were introduced into human EGLN1 cDNA in a baculovirus vector40 with a sequence encoding a C-terminal Flag-His tag using the primer pairs listed in Supplementary Table 5 and the QuikChange site- directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The resulting recombinant vectors were sequenced for the correct mutations. The vectors were cotransfected into Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells (Invitrogen) with BaculoGold DNA (Pharmingen) by calcium phosphate transfection, and the recombinant baculoviruses generated were amplified. Mutant and wild-type PHD2 proteins were expressed in H5 insect cells (Invitrogen) cultured in suspension in Sf900IISFM serum-free medium (Invitrogen) and were purified to near homogeneity with anti-Flag M2 affinity material, as described40. Kinetic analyses of the PHD2 mutants in comparison to wild-type enzyme were performed by an assay measuring the hydroxylation-coupled stoichiometric release of 14C-labeled CO2 from 2-oxo[1-14C]glutarate in a reaction volume of 0.250 ml (ref. 18). Equal amounts of freshly purified wild-type and mutant enzyme were used as catalysts. The Km and Vmax values for the mutant enzymes relative to wild-type enzyme for a synthetic peptide DLDLEMPAYIPMDDDFQL (DLD19) and HIF-2αODDD produced and purified in Escherichia coli41 were determined by varying the concentration of the substrate while keeping the concentrations of the cosubstrates constant. The Km and Vmax values for oxygen were determined by varying the oxygen concentration in a hypoxia workstation (InVivo2 400, Ruskinn Technology) and keeping the concentration of the substrate (HIF-2αODDD) and those of the other cosubstrates constant. The Km values for 2-oxoglutarate were determined under normoxia by varying the concentration of 2-oxoglutarate while keeping those of the substrate (DLD19) and the other cosubstrates constant. Statistical analyses comparing the Km and Vmax values for each mutant PHD2 with the values for wild-type enzyme were performed using the Student’s two-tailed t test.

EGLN1 shRNA knockdown and rescue assays

EGLN1 cDNA (wild-type and variant) was subcloned into pLenti-Ubcp-Flag-HA-gateway-PGK-HYG expression vector using Gateway technology (Life Technologies), and constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Hep3B cells (American Type Culture Collection; tested negative for mycoplasma) were infected with lentiviruses encoding Venus fluorescent protein or the PHD2 constructs. After selection in 200 μg/ml hygromycin, cells were infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA or EGLN1 shRNA (TRCN0000001042, Broad Institute TRC shRNA library) and were selected in 2 μg/ml puromycin. Cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 200 μg/ml hygromycin, 2 μg/ml puromycin and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in the presence of 21% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. For hypoxia experiments, cells were grown instead in 1% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cell extracts were prepared on ice with 1× lysis buffer (50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) supplemented with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Roche Applied Science), resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked in TBST with 5% nonfat milk and probed with monoclonal antibody to HIF-2α (1:1,000 dilution; generated in house), monoclonal antibody to PHD2 (1:1,000 dilution; D31E11, Cell Signaling Technology) and monoclonal antibody to tubulin (1:10,000 dilution; T5168, Sigma-Aldrich). Bound proteins were detected with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Pierce) and SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce). Total (endogenous and transgene-expressed) EGLN1 transcript levels were quantified using the primers described in Supplementary Table 5.

Analysis of erythroid progenitors: BFU-E sensitivity assays

Erythroid colonies (BFU-Es) were grown from peripheral blood mononuclear cells for 14 d in the presence of different concentrations of EPO (Stemcell Technologies)42. Briefly, mononuclear cells from peripheral blood were isolated with Histopaque 1077 (Sigma-Aldrich) and cultured at a final density of 6 × 105 cells/ml in Methocult H-4531 medium (Stemcell Technologies) in 35-mm Petri dishes in duplicate. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 21% O2 for normoxic conditions. Culture under reduced oxygen tension was achieved using a modular incubator chamber (Billups Rothenberg), which was flushed for 10 min with a gas mixture of 5% O2, 5% CO2 and 90% N2 or 1% O2, 5% CO2 and 94% N2, sealed and placed at 37 °C in a conventional cell incubator. After 14 d of culture, colonies from plates with different EPO concentrations were counted and compared with the controls, as previously described42. In addition, each colony was imaged in an identical setting using a Stereomicroscope Stemi 2000-C (Carl Zeiss Microscopy) connected to an Olympus DP Digital camera (Olympus Imaging America) at a fixed magnification (40×). Digital images of every colony were analyzed using a pixel count algorithm provided in ImageScope software (Aperio) to calculate the area occupied by each individual colony (pixel count) as a measure of colony size. Colonies were individually collected, and RNA was extracted for expression studies. For colony growth in 15 mU and 3,000 mU concentrations of EPO, data were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA to compare colony counts by group at different oxygen concentrations and assess interaction effects (oxygen-by-group interactions). The PROC MIXED procedure (a component of the SAS System) was used to generate these mixed models. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, Version 9.3 of the SAS System (2012 SAS Institute).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

P.K. is supported by Academy of Finland grants 120156, 140765 and 218129, the S. Juselius Foundation, the Finnish Cultural Foundation and the Finnish Cancer Organizations. B.O. is supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Mentored Career Development Award HL119355-01. J.X. is supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (HG005846). G.R.-L. is supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (grant 2012CB518200) and by the Program of International Science and Technology Cooperation of China (grant 2011DFA32720). S.S. is supported by US NIH grant P01CA108671. T.S.S. is supported by the US NIH T32 Postdoctoral Fellowship HL098062. L.B.J. is supported by the University of Utah Seed Grant Program for studies of hypoxic adaptation. G.L.S. is supported by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Cell Engineering. J.T.P. is supported by US NIH grant P01CA108671, a Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award and the University of Utah Seed Grant Program for studies of hypoxic adaptation.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

F.R.L. screened and discovered the PHD2 alteration, designed the experiment, performed expression studies and data analysis, and drafted and edited the manuscript. M.M. and P.K. performed the kinetic studies and wrote and edited the manuscript. C.H., J.X., T.S.S. and L.B.J. analyzed array data, characterized and estimated the origin of the variants and edited the manuscript. P.A.K. and G.R.-L. hosted F.R.L., T.T. and J.T.P. in their countries, assisted with the recruitment of subjects in India and China, and obtained necessary local regulatory and institutional review board documents. T.W. helped organize and assisted with the collection and phenotyping of samples from the Tibetan plateau. P.G. helped organize collection and assisted in the preparation and extraction of DNA in India. S.S. performed the erythroid colony assays, interpreted their results and edited the manuscript. M.E.S. performed the quantification of mean size and hemoglobinization of BFU-Es. A.W. designed and performed the statistical analysis of changes in BFU-E hypersensitivity to EPO. V.G. and D.A.M. critically revised the concept, contributed to the intellectual content and design, and gave final approval of the manuscript. G.L.S. critically revised the concept, contributed to the intellectual content and wrote the manuscript. B.O., W.G.K., E.L. and T.M.K. performed the knockdown study and edited the manuscript. J.T.P. conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote and edited the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

URLs. 1000 Genome Phase I: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?rs=12097901.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Beall CM. Two routes to functional adaptation: Tibetan and Andean high-altitude natives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104 (suppl 1):8655–8660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701985104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prchal JT. Production of Erythrocytes. McGraw Hill; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prchal JT. Secondary Polycythemia (Erythrocytosis) McGraw Hill; New York: 2010. pp. 823–839. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simonson TS, et al. Genetic evidence for high-altitude adaptation in Tibet. Science. 2010;329:72–75. doi: 10.1126/science.1189406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beall CM, et al. Natural selection on EPAS1 (HIF2α) associated with low hemoglobin concentration in Tibetan highlanders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11459–11464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002443107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yi X, et al. Sequencing of 50 human exomes reveals adaptation to high altitude. Science. 2010;329:75–78. doi: 10.1126/science.1190371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenzo FR, et al. Novel PHD2 mutation associated with Tibetan genetic adaptation to high altitude hypoxia. ASH 52nd Annual Meeting; Orlando, FL: ASH; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian H, McKnight SL, Russell DW. Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes Dev. 1997;11:72–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang GL, Semenza GL. Characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and regulation of DNA binding activity by hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21513–21518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prabhakar NR, Semenza GL. Adaptive and maladaptive cardiorespiratory responses to continuous and intermittent hypoxia mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors 1 and 2. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:967–1003. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang GL, Semenza GL. General involvement of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in transcriptional response to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4304–4308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapitsinou PP, et al. Hepatic HIF-2 regulates erythropoietic responses to hypoxia in renal anemia. Blood. 2010;116:3039–3048. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon D, Ponka P, Prchal JT. Hypoxia. 5 Hypoxia and hematopoiesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C1215–C1222. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00044.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon D, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 deficiency results in dysregulated erythropoiesis signaling and iron homeostasis in mouse development. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25703–25711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pineda Torra I, Jamshidi Y, Flavell DM, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Characterization of the human PPARα promoter: identification of a functional nuclear receptor response element. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1013–1028. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.5.0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xing J, et al. Genomic analysis of natural selection and phenotypic variation in high-altitude mongolians. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huff CD, et al. Crohn’s disease and genetic hitchhiking at IBD5. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:101–111. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirsilä M, Koivunen P, Gunzler V, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J. Characterization of the human prolyl 4-hydroxylases that modify the hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30772–30780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ang SO, et al. Disruption of oxygen homeostasis underlies congenital Chuvash polycythemia. Nat Genet. 2002;32:614–621. doi: 10.1038/ng1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loeffler M, Herkenrath P, Wichmann HE, Lord BI, Murphy MJ., Jr The kinetics of hematopoietic stem cells during and after hypoxia A model analysis. Blut. 1984;49:427–439. doi: 10.1007/BF00320485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cipolleschi MG, et al. Severe hypoxia enhances the formation of erythroid bursts from human cord blood cells and the maintenance of BFU-E in vitro. Exp Hematol. 1997;25:1187–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drmanac R, et al. Human genome sequencing using unchained base reads on self-assembling DNA nanoarrays. Science. 2010;327:78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1181498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bigham AW, et al. Identifying positive selection candidate loci for high-altitude adaptation in Andean populations. Hum Genomics. 2009;4:79–90. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-2-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albiero E, et al. Isolated erythrocytosis: study of 67 patients and identification of three novel germline mutations in the prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 (PHD2) gene. Haematologica. 2012;97:123–127. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.039545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albiero E, et al. Analysis of the oxygen sensing pathway genes in familial chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms and identification of a novel EGLN1 germline mutation. Br J Haematol. 2011;153:405–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ladroue C, et al. Distinct deregulation of the hypoxia inducible factor by PHD2 mutants identified in germline DNA of patients with polycythemia. Haematologica. 2012;97:9–14. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.044644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Percy MJ, et al. Two new mutations in the HIF2A gene associated with erythrocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:439–442. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Percy MJ, et al. A family with erythrocytosis establishes a role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:654–659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aggarwal S, et al. EGLN1 involvement in high-altitude adaptation revealed through genetic analysis of extreme constitution types defined in Ayurveda. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18961–18966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006108107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ang SO, et al. Endemic polycythemia in Russia: mutation in the VHL gene. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2002;28:57–62. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2002.0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Percy MJ, et al. A novel erythrocytosis-associated PHD2 mutation suggests the location of a HIF binding groove. Blood. 2007;110:2193–2196. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-084434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Percy MJ. Familial erythrocytosis arising from a gain-of-function mutation in the HIF2A gene of the oxygen sensing pathway. Ulster Med J. 2008;77:86–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simonson TS, McClain DA, Jorde LB, Prchal JT. Genetic determinants of Tibetan high-altitude adaptation. Hum Genet. 2012;131:527–533. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ge RL, et al. Metabolic insight into mechanisms of high-altitude adaptation in Tibetans. Mol Genet Metab. 2012;106:244–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xing J, et al. Toward a more uniform sampling of human genetic diversity: a survey of worldwide populations by high-density genotyping. Genomics. 2010;96:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xing J, et al. Fine-scaled human genetic structure revealed by SNP microarrays. Genome Res. 2009;19:815–825. doi: 10.1101/gr.085589.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huff CD, et al. Maximum-likelihood estimation of recent shared ancestry (ERSA) Genome Res. 2011;21:768–774. doi: 10.1101/gr.115972.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Browning SR, Browning BL. Rapid and accurate haplotype phasing and missing-data inference for whole-genome association studies by use of localized haplotype clustering. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1084–1097. doi: 10.1086/521987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstein DB, Schlotterer C. Microsatellites: Evolution and Applications; Estimating the Age of Mutations Using Variation at Linked Markers. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirsilä M, et al. Effect of desferrioxamine and metals on the hydroxylases in the oxygen sensing pathway. FASEB J. 2005;19:1308–1310. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3399fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koivunen P, Hirsila M, Kivirikko KI, Myllyharju J. The length of peptide substrates has a marked effect on hydroxylation by the hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl 4-hydroxylases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28712–28720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604628200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swierczek SI, et al. Methylation of AR locus does not always reflect X chromosome inactivation state. Blood. 2012;119:e100–e109. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-390351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.