Abstract

Evidence suggests that over-expression of TWIST, an epithelial-mesenchymal transition inducer, might have a correlation with cancer progression and chemoresistance. However, its roles in radioresistance of cancer have rarely been reported. High TWIST expression was detected in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) and associated with poor prognosis. Thus, in the present study, we aimed to determine whether knockdown of TWIST can increase radiosensitivity of NPC cells. Chitosan-encapsulated TWIST-siRNA nanoparticles were constructed and used to silence TWIST expression in CNE2 cells. The cell viability and apoptosis as well as possible MAPKs pathways were assessed after irradiation treatment. The results showed that the nanoparticles successfully suppressed TWIST expression in CNE2 cells, and TWIST depletion significantly sensitized CNE2 cells to irradiation by inducing activation of ERK pathway but not JNK or p-38 pathways. The data suggested that TWIST depletion might be a promising approach sensitizing NPC cells to irradiation. Further investigations are needed to confirm the results.

Keywords: TWIST, RNA interference, nanoparticle, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, radioresistance, signaling pathways

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) is an epithelial malignant tumor originates from nasopharyngeal region, with high incidence in Southeast Asia and North Africa. Radiotherapy has been the effective primary mode of treatment for locoregional NPC for a period of time [1]. Nevertheless, despite great achievements in radiation technology, local recurrence, nodal and distant metastasis still occurs in a proportion of patients who undergo radiotherapy mostly due to the existence of radioresistance [2]. Hence, to find new methods for increasing the radiosensitivity of NPC cells to irradiation is warranted and gene therapy might be a promising approach.

Previously, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a key event of embryogenesis, plays fundamental roles in the differentiation of normal tissues and organs [3]. EMT may be inhibited for maintaining epithelial integrity and homeostasis in adult tissue and aberrant activation of EMT in epithelial tumors usually implies the malignant tendency of the disorders [4]. Thus, EMT has been regarded as a key process of cancer progression. Reports confirmed that EMT might be a critical event in invasion and metastasis for nasopharyngeal carcinoma [5,6]. Some molecules such as TWIST, Snail and Slug are thought to be inducers of EMT [7].

TWIST, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, has been detected to be over-expressed in a variety of carcinomas. Recent reports have shown that high expression of TWIST is associated with tumor aggressive of renal cell cancer [8], bladder cancer [9] and cervical cancer [10]. Besides, TWIST mediates Benzo(a)pyrene-enhanced malignant capacity of lung cancer cells [11] and act as a key factor promoting Kindlin-3-induced breast cancer metastasis possibly by inducing angiogenesis [12]. A recent meta-analysis revealed that elevated TWIST expression in cancers might indicate poor prognosis [13]. Thus, TWIST plays an important role in the genesis and progression of carcinomas, and targeting TWIST has been regarded as a promising treatment for cancers [14].

EMT has been indicated to have a correlation with radioresistance of cancer cells [15]. Nevertheless, with respect to TWIST, a number of studies have focused on its roles in chemoresistance of cancer cells to anti-cancer drugs [16,17]. To our knowledge, the roles of TWIST in radioresistance of cancer cells have scarcely been published in the open literature. Our recent study showed that over-expression of TWIST was detected in nasopharyngeal carcinoma [18], leading us to hypothesize that TWIST suppression might increase radiosensitivity of NPC cells to irradiation.

To test this hypothesis, in the present study we aimed to knock down TWIST expression in NPC cells in order to increase their sensitivity to irradiation by using RNA interference technique. Notably, poor stability of siRNA in culture and in vivo, and low cellular uptake markedly compromised the gene silencing effect [19]. To overcome the disadvantages, a number of virus vectors such as retrovirus, lentivirus and adenovirus have been explored for siRNA delivery [20]. Nevertheless, though the virus carriers achieved high transfection efficiency, the safety issues hampered their clinical application. Thus, a safe and efficient carrier for delivery of siRNA was required. In the present study, we used a promising non-viral vector, nanoparticle, for siRNA delivery. TWIST expression has been successfully silenced in cultured NPC cells and its roles in radiosensitivity of the cells were also assessed. Then, possible signaling mechanisms in this process were further investigated.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of Chitosan/pshRNA nanoparticles

TWIST siRNA contained in pSilencer™ 2.1-U6 neo plasmid vectors (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) were synthesized as described in our previous study [21]. In brief, the TWIST siRNA inserting sequence had sense and antisense sequences as follows: TWIST sense sequence: 5’-GATCCGCTGAGCAAGATTCAGACCTTCAAGAGAGGTCTGAATCTTGCTCAGCTTTTTTGGAAA-3’; antisense sequence: 5’-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAAGCTGAGCAAGATTCAGACCTCTCTTGAAGGTCTGAATCTTGCTCAGCG-3’. The unrelated nonspecific scrambled oligonucleotide was designed as control: sense: 5’-GATCCGTATTGCCTAGCATTACGTTTCAAGAGAACGTAATGCTAGGCAATACTTTTTTGGAAA-3’; antisense: 5’-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAA GTATTGCCTAGCATTACGTTCTCTTGAAACGTAATGCTAGGCAATACG-3’. Single strand sense and antisense sequences were annealed into oligonucleotide pairs containing terminal BamHI and HindIII restriction sites. As a result, TWIST siRNA vector and control siRNA vector were generated.

The generated plasmids were diluted with 5 mmol/L sodium sulfate solution to a concentration of 0.20 g/L, which were then heated at 55°C for 45 min. Likewise, a solution of Chitosan (CS) at a concentration of 0.02% was also heated at 55°C for 45 min. Next, these two solutions were combined and vortexed at maximal speed for 1 min at 25°C and then incubated for 1 h. The constructed nanoparticles were named as TWIST-CS/siRNA and control-CS/ siRNA, respectively. The morphological characteristics of nanoparticles were observed by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Cell culture and plasmid transfection

The human nasopharyngeal cell line, CNE2 cell line, was obtained from ATCC and conserved in our laboratory. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, HyClone, Logan, UT) containing 10% fetal bovine serum in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 3.0×105 cells/well, respectively. DMEM comprising 40 μl nanoparticle solution (1.5 ml) was added into the wells. After 6 h incubation, the medium was replaced by DMEM. Stably expressed clones were selected by using medium containing G418 (500 μg/ml) for 21 days. The stable transfectants were named CNE2-siTWIST and CNE2-siControl respectively.

Colony survival assay

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates (1000 cells/well) and they were treated with different doses of X-ray radiation. The radiation doses were 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 Gy, respectively, during which the dose efficiency was 300 cGy/min. The cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then they were maintained at 37°C for the formation of cell colonies. After an incubation period of 14 days, the colonies were fixed with methanol and stained with crystal violet. The colonies were visually counted with a cutoff value of 50 viable cells.

Cell viability assay

Cells were plated in 96-well plates (1×104 cells/well). MTT assays were used to assess cell viability. 200 μl sterile MTT dye (5 mg/ml, sigma, USA) was added. After 4 h incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, MTT medium mixture was removed and 200 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a multi-well spectrophotometer (Thermo Electron, Andover, USA).

Apoptosis analysis assay

Cells were plated on polylysine-coated slides and washed with twice PBS buffer and resuspended at a concentration of 1×105 cells/ml. Apoptosis was evaluated by using the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection kit (Beytime, China). 5 μl Annexin V-FITC was added after the addition of 195 μl binding buffer, and the cells were incubated for 10 min at 25°C. After the addition of 190 μl binding buffer, 10 μl propidium iodide (PI) were added and the cells were placed on ice in the dark. Then, the samples were analyzed by flow cytometry within 1 h.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR assay

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) and first strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg total RNA using Oligo d(T) primer (Invitrogen) and ReveTra Ace (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). PCR was done on the cDNA product using the following primers for TWIST: F: 5’-GGAGTCCGCAGTCTTACGAG-3’ and R: 5’-TCTGGAGGACCTGGTAGAGG-3’. for GAPDH: F: 5’-CAGTGCCAGCCTCGTCTCAT-3’ and R: 5’-AGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTTC-3’. Thermal cycler parameters included one cycle at 94°C for 0.5 min, and 30 cycles involving denaturation at 94°C for 30 s annealing at 58°C for 45 s and extension at 72°C for 60 s. Extension was performed for an additional 10 min after the completion of the indicated cycles. The bands were quantified by densitometric scanning of band intensities and normalized to the levels of GAPDH using Image-Pro Plus 5.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA).

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested, washed with ice-cold PBS, and lysed with RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris base pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 mM Na3VO4) supplemented with protease inhibitor. Proteins were running on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, USA). Blots were then incubated in fresh blocking solution with an appropriate dilution of primary antibody at 4°C for 24 h. the membranes were visualized by electrochemiluminescence.

The sources of antibodies were as follows: TWIST, GAPDH rabbit polyclonal (Abcam); p-JNK, JNK, ERK, p-ERK, p-38, p-p38, caspase-3 mouse monoclonal (Santa cruz).

The bands were visualized and quantified using Image-Pro Plus 5.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). The p-JNK, pERK, p-p38 band intensities were normalized to JNK, ERK, p-38 band intensities respectively and the intensities of TWIST and Caspase-3 were adjusted by the GAPDH band intensity.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean value ± SD. Differences between groups were analyzed with Analysis of Variances (ANOVA) or a t-test. The analyses were performed by utilizing SPSS for Windows version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Morphological characteristics of CS/siRNA nanoparticles

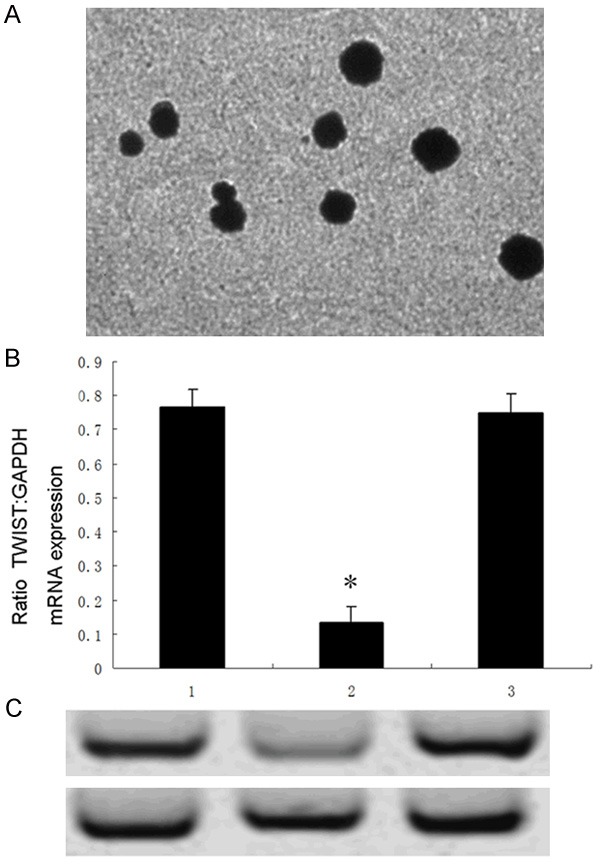

The nanoparticles of CS/siRNA plasmid were nearly 90-120 nm in size and approximately round shape with smooth surface, implying that the nanoparticles were successfully constructed (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Transmission electron microscopic image of CS/siRNA nanoparticles (A). Effects of nanoparticles on TWIST mRNA and protein expressions assessed by RT-PCR and western blot assays. Expression of TWIST mRNA (B) and protein (C) of CNE2-siTWIST cells were significantly lower than those of CNE2-nontransfection or CNE2-siControl cells, respectively (*P<0.01 vs 1 or 3). 1, CNE2-nontransfection; 2, CNE2-siTWIST; 3, CNE2-siControl.

Nanoparticle-mediated RNAi led to down-regulation of TWIST

To test whether nanoparticles could down-regulate TWIST expression in CNE2 cells, cells were divided into three groups, namely, CNE2-siTWIST, CNE2-siControl and CNE2-nontransfection, respectively. CNE2-siTWIST was transfected with TWIST-CS/siRNA vector, while CNE2-siControl was transfected with control-CS/siRNA vector. CNE2-nontransfection was not transfected with any vectors as a blank control. RT-PCR and western blot assays were used to detect mRNA and protein expression of TWIST.

As expected, expression levels of TWIST both mRNA and protein in CNE2-siTWIST cells were significantly lower than those in CNE2-siControl or CNE2-nontransfection cells analyzed by RT-PCR and immunoblotting respectively (Figure 1B, 1C), suggesting that nanoparticle-mediated RNAi might be an effective method for TWIST suppression in CNE2 cells.

TWIST suppression enhanced sensitivity of CNE2 cells to radiation

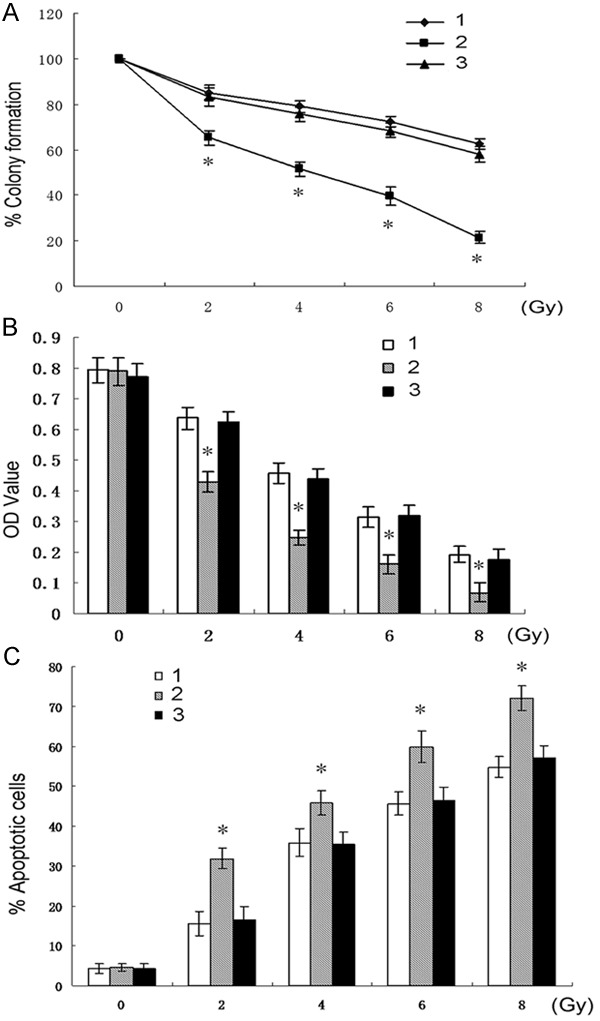

Colony survival assay is a good method for evaluation of radiosensitivity. We thus aimed to determine the effects of TWIST-silencing on the colony survival of CNE2 cells in presence of radiation. As shown in Figure 2A, TWIST-silenced cells, CNE2-siTWIST, presented low colony formation capacity compared with the other two control cells, respectively, indicating that TWIST-silencing increased CNE2 cell sensitivity in response to radiation.

A.

Colony survival curves of the three types of cells in presence of different doses of radiation (0-8 Gy), respectively. (*P<0.01 vs 1 or 3). Effects of radiation (0-8 Gy) on the three types of cells assessed by MTT (B) and apoptosis assays (C), respectively (*P<0.01 vs 1 or 3). 1, CNE2-nontransfection; 2, CNE2-siTWIST; 3, CNE2-siControl.

To further assess the roles of TWIST-silencing in radiosensitivity of NPC cells, the viability and apoptosis of CNE2 were determined in presence of irradiation. The results showed that knockdown of TWIST resulted in a significant decrease in cell viability and an increase in apoptosis of CNE2 cells in response to radiation in a dose-dependent manner compared with those of CNE2-siControl or CNE2-nontransfection cells, respectively (Figure 2B, 2C). Notably, without X rays (0 Gy), the results of MTT and apoptosis assays showed little difference among the three groups of cells, demonstrating that sole silence of TWIST slightly trigger spontaneous apoptosis of CNE2 cells. In the following research, we used 2 Gy for further experiments.

Knockdown of TWIST increased irradiation-induced CNE2 cell apoptosis possibly through activation of MAPK pathway

To learn possible underlying mechanisms by which TWIST suppression induces radiosensitivity of CNE2 cells, we conducted further experiments.

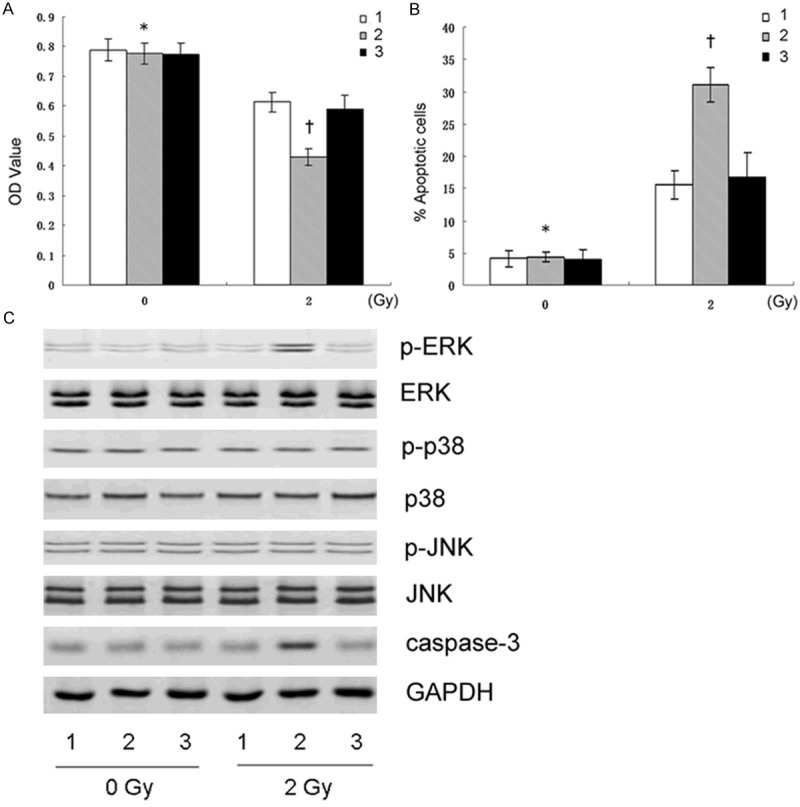

Cells were divided into two groups, both of which contained three types of cells respectively, namely, CNE2-nontransfection, CNE2-siTWIST, and CNE2-siControl cells. The two groups were exposed to 2 Gy (radiation group) and 0 Gy (control group) irradiation, respectively. Then the cell viability and apoptosis were analyzed by MTT and apoptosis assays (Figure 3A, 3B). Moreover, proteins of caspase-3 and MAPK pathways including JNK, p-JNK, ERK, p-ERK, p-38, and p-p38 were further assessed by western blot.

Figure 3.

The results of the three types of cells treated with 2 Gy X-rays or without irradiation. The cell viability and apoptosis assessed by MTT (A) and Flow cytometry (B) respectively (†P<0.01 vs 1 and 3; *P<0.01 vs †). (C) Expressions of the Caspase-3 and MAPK pathway-related proteins assessed by western blot. 1, CNE2-nontransfection; 2, CNE2-siTWIST; 3, CNE2-siControl.

The results showed that p-ERK expression was significantly elevated in CNE2-siTWIST cells in the radiation group, accordingly accompanied by increased cell apoptosis and decreased cell proliferation, as well as increased Casepase-3 expression (Figure 3C). The data revealed that the increased radiosensitivity of CNE2-siTWIST cells might have an association with activation of ERK pathway, rather than JNK or p-38 pathways.

ERK signaling pathway played partial roles in TWIST-silencing-induced apoptosis in response to irradiation

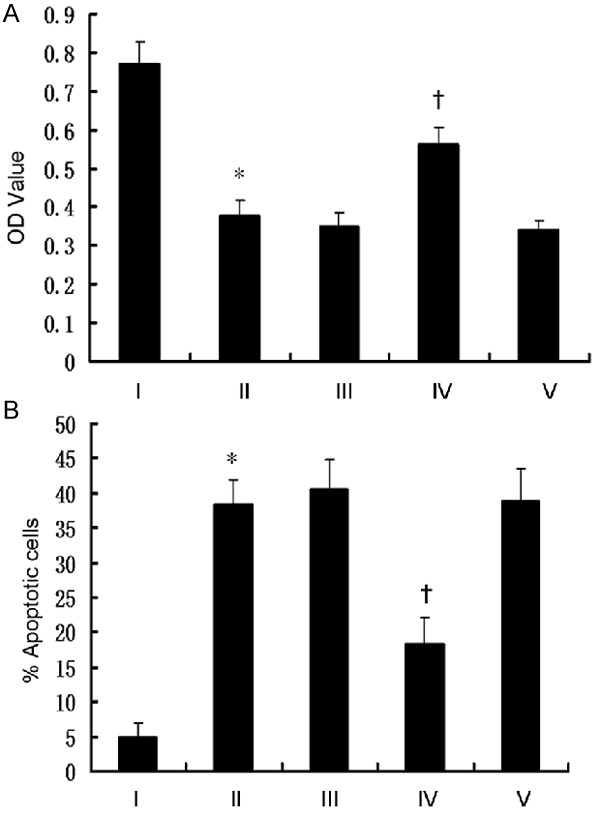

To further test the possible roles of MAPK pathways, CNE2-siTWIST cells were divided into five groups, and marked as I, II, III, IV, and V, respectively. Cells in group I was treated with DMEM and was not exposed to irradiation (0 Gy) as a control, whereas cells in the remaining four groups were treated with DMEM and exposed to 2 Gy X-rays, respectively. Nevertheless, cells in group III were pre-treated with 10 µM SP600125 (a specific JNK inhibitor), in group IV with 10 µM PD98059 (a specific ERK inhibitor), and in group V with 10 µM SB203580 (a specific p-38 inhibitor) for 2 h prior to X-ray exposure. Next, the cell viability and apoptosis were assessed.

The results showed that there is a decrease in cell apoptosis in group IV (ERK inhibitor), compared to group II, IV and V, respectively, confirming the involvement of ERK activation in sensitizing CNE2-siTWIST cells to irradiation. However, we also observed an increase in cell apoptosis in group IV, compared with that of group I (without radiation). The data showed that ERK pathway inhibition could only partly reduce CNE2-siTWIST cell apoptosis caused by radiation, suggesting this pathway as one of the signaling pathways during this period (Figure 4). However, in addition to this one, other unknown pathways might also play a role in this process.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the results of CNE2-siTWIST cells treated with DMEM (I), radiation (II), radiation + SP600125 (III), radiation + PD98059 (IV) and radiation + SB203580 (V). The cell viability (A) and apoptosis (B) were assessed (*P>0.05 vs III and V; †P<0.05 vs I and II).

Discussion

In the present study, we established Chitosan-encapsulated siRNA-TWIST vectors and successfully down-regulated TWIST expression in cultured NPC cells, thus increasing sensitivity of the cells to irradiation. Activation of ERK pathway might play an important role in this process.

In general, the silence effect of siRNA has been attenuated by the poor cellular internalization due to the negative surface charge of both nucleotide sequence and cell membranes [22]. In the present study, the siRNA plasmids were coated by positive-charge-featured Chitosan that is one of the abundant, renewable, nontoxic and biodegradable carbohydrate polymers because of its natural origin from the N-deacetylated derivative of chitin. Chitosan has thus been used as a potential drug-delivery carrier for cancer research [23]. The positive-charge features of Chitosan facilitate its interaction with negative-charged targets including tumor cell membrane, thus markedly increasing cellular uptake of siRNA vectors [24]. Moreover, the dual solubility in both lipid and aqueous phase of Chitosan expands considerably the range of its application [25]. Therefore, we used Chitosan as a non-toxic vector for nanoparticle construction. The results confirmed the effectiveness of gene silencing.

EMT phenotype has been thought to have a correlation with radioresistance of cancer cells [26]. However, the roles and mechanisms of TWIST in radioresistance have rarely been reported. Emerging evidence suggests possible involvement of some signaling pathways in irradiation-induced cancer cell apoptosis. MAPKs, mainly comprising ERK, p38MAPKs, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), are suggested to associate with resistance of cancer cells in response to radiation [27]. Huang et al. [28] reported the involvement of ERK pathway in glioma radioresistance. In a study about head and neck cancer [29], inhibition of p38 and ERK might increase sensitivity of cancer cells to irradiation. P38 activation was also indicated to correlate with radioresistance of breast cancer [30]. Conversely, in a recent study, P38 was not implicated in cellular viability after radiation exposure [31]. Thus, the above evidence suggested that the roles of MAPK pathways in radioresistance might differ in various cancer cells. In the present study, we only observed that activation of ERK might mediate radiation-induced apoptosis in TWIST-silenced NPC cells, while inhibition of ERK significantly attenuated this effect, indicating that activation of ERK might provide an apoptotic signal when TWIST expression was down-regulated and the radiation treatment was applied. Notably, inhibition of ERK could not completely reverse the effect, implying that ERK might only one of the major pathways in this process. In addition to ERK, other signaling pathways might also play critical roles in this issue. Nevertheless, the precise pathways are largely unknown and further studies are needed.

To our knowledge, our data provided the first insight into the roles and possible mechanisms of TWIST-silencing in the sensitivity of CNE2 cells to irradiation. The results suggest that TWIST depletion before irradiation might be a potential adjuvant treatment strategy for NPC. First, sole deletion of TWIST in CNE2 cells rarely resulted in spontaneous apoptosis. Second, the occurrence of radioresistance seriously leads to poor therapeutic effects of radiotherapy on NPC. Accordingly, high-dose of irradiation would be clinically applied and the side-effects of X-rays such as tumorigenicity and bone marrow depression might be increased. Moreover, the probability of local recurrence and metastasis might be elevated because of the treatment failure. However, third, TWIST depletion could significantly sensitize CNE2 cells to apoptosis caused by irradiation. Therefore, TWIST depletion is likely to be an effective and promising adjuvant treatment approach before conventional radiotherapy, which might lead to lower-dose radiation application and a reduction of side-effects.

Several limitations might be included in the present study. First, we only used CNE2, a well characterized NPC cell line, to determine the roles of TWIST-silencing in radioresistance. Future studies using other cell lines might increase power for the demonstration. Second, only a small proportion of signaling pathways underlying the enhancement of radiosensitivity were assessed. Nevertheless, other pathways that might be involved in this process need to be deeply determined in further investigations. Third, the present study concerned the roles of TWIST-silencing in vitro, while further in vivo investigations might strengthen the significance of this study. However, the data implicate TWIST as a potential target for sensitizing NPC cells to irradiation.

In conclusion, we successfully suppressed TWIST expression in CNE2 cells by using Chitosan-coated siRNA nanoparticles, leading to an increase in radiation-induced CNE2 cell apoptosis. Activation of ERK might play a critical role mediating the cell apoptosis. The data suggested that TWIST depletion might be a promising adjuvant treatment approach that might sensitize NPC cells to irradiation. Future investigations are needed to confirm the results.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81101145) and Special Foundation of China Postdoctoral Science (2012T50851).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Yoshizaki T, Ito M, Murono S, Wakisaka N, Kondo S, Endo K. Current understanding and management of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2012;39:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luftig M. Heavy LIFting: tumor promotion and radioresistance in NPC. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4999–5001. doi: 10.1172/JCI73416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schindeler A, Kolind M, Little DG. Cellular transitions and tissue engineering. Cell Reprogram. 2013;15:101–106. doi: 10.1089/cell.2012.0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinestel K, Eder S, Schrader AJ, Steinestel J. Clinical significance of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Clin Transl Med. 2014;3:17. doi: 10.1186/2001-1326-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo W, Li S, Peng B, Ye Y, Deng X, Yao K. Embryonic stem cells markers SOX2, OCT4 and Nanog expression and their correlations with epithelial-mesenchymal transition in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu HH, Zhu XY, Zhou MH, Cheng GY, Lou WH. Effect of WNT5A on epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its correlation with tumor invasion and metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7:488–491. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz VM, Vinas-Castells R, Garcia de Herreros A. Regulation of the protein stability of EMT transcription factors. Cell Adh Migr. 2014;8:418–428. doi: 10.4161/19336918.2014.969998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohba K, Miyata Y, Matsuo T, Asai A, Mitsunari K, Shida Y, Kanda S, Sakai H. High expression of Twist is associated with tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:3158–3165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao J, Dong D, Sun L, Zhang G. Prognostic significance of the epithelial-tomesenchymal transition markers e-cadherin, vimentin and twist in bladder cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2014;40:179–189. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2014.02.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang T, Li Y, Tuerhanjiang A, Wang W, Wu Z, Yuan M, Wang S. Correlation of Twist upregulation and senescence bypass during the progression and metastasis of cervical cancer. Front Med. 2014;8:106–112. doi: 10.1007/s11684-014-0307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Zhai W, Wang H, Xia X, Zhang C. Benzo(a)pyrene promotes A549 cell migration and invasion through up-regulating Twist. Arch Toxicol. 2014;89:451–8. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sossey-Alaoui K, Pluskota E, Davuluri G, Bialkowska K, Das M, Szpak D, Lindner DJ, Downs-Kelly E, Thompson CL, Plow EF. Kindlin-3 enhances breast cancer progression and metastasis by activating Twist-mediated angiogenesis. FASEB J. 2014;28:2260–2271. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-244004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang P, Hu P, Shen H, Yu J, Liu Q, Du J. Prognostic role of Twist or Snail in various carcinomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2014;44:1072–1094. doi: 10.1111/eci.12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan MA, Chen HC, Zhang D, Fu J. Twist: a molecular target in cancer therapeutics. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:2497–2506. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theys J, Jutten B, Habets R, Paesmans K, Groot AJ, Lambin P, Wouters BG, Lammering G, Vooijs M. E-Cadherin loss associated with EMT promotes radioresistance in human tumor cells. Radiother Oncol. 2011;99:392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Li L, Zeng J, Wu K, Zhou J, Guo P, Zhang D, Xue Y, Liang L, Wang X, Chang LS, He D. Twist confers chemoresistance to anthracyclines in bladder cancer through upregulating P-glycoprotein. Chemotherapy. 2012;58:264–272. doi: 10.1159/000341860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuti SV, Mor G, Li P, Yin G. TWIST and ovarian cancer stem cells: implications for chemoresistance and metastasis. Oncotarget. 2014;5:7260–7271. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhuo X, Chang A, Huang C, Yang L, Xiang Z, Zhou Y. Expression of TWIST, an inducer of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and its clinical significance. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:8862–8868. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higuchi Y, Kawakami S, Hashida M. Strategies for in vivo delivery of siRNAs: recent progress. BioDrugs. 2010;24:195–205. doi: 10.2165/11534450-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Couto LB, High KA. Viral vector-mediated RNA interference. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhuo WL, Wang Y, Zhuo XL, Zhang YS, Chen ZT. Short interfering RNA directed against TWIST, a novel zinc finger transcription factor, increases A549 cell sensitivity to cisplatin via MAPK/mitochondrial pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:1098–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schroeder A, Levins CG, Cortez C, Langer R, Anderson DG. Lipid-based nanotherapeutics for siRNA delivery. J Intern Med. 2010;267:9–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prabaharan M. Chitosan-based nanoparticles for tumor-targeted drug delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;72:1313–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katas H, Raja MA, Lam KL. Development of Chitosan Nanoparticles as a Stable Drug Delivery System for Protein/siRNA. Int J Biomater. 2013;2013:146320. doi: 10.1155/2013/146320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee DW, Lim C, Israelachvili JN, Hwang DS. Strong adhesion and cohesion of chitosan in aqueous solutions. Langmuir. 2013;29:14222–14229. doi: 10.1021/la403124u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marie-Egyptienne DT, Lohse I, Hill RP. Cancer stem cells, the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) and radioresistance: potential role of hypoxia. Cancer Lett. 2013;341:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang FR, Loke WK. Molecular mechanisms of low dose ionizing radiation-induced hormesis, adaptive responses, radioresistance, bystander effects, and genomic instability. Int J Radiat Biol. 2014:1–15. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2014.937510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang L, Li B, Tang S, Guo H, Li W, Huang X, Yan W, Zou F. Mitochondrial K Channels Control Glioma Radioresistance by Regulating ROS-Induced ERK Activation. Mol Neurobiol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8888-1. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laban S, Steinmeister L, Gleissner L, Grob TJ, Grenman R, Petersen C, Gal A, Knecht R, Dikomey E, Kriegs M. Sorafenib sensitizes head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells to ionizing radiation. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin F, Luo J, Gao W, Wu J, Shao Z, Wang Z, Meng J, Ou Z, Yang G. COX-2 promotes breast cancer cell radioresistance via p38/MAPK-mediated cellular anti-apoptosis and invasiveness. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:2817–2826. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0840-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de la Cruz-Morcillo MA, Garcia-Cano J, Arias-Gonzalez L, Garcia-Gil E, Artacho-Cordon F, Rios-Arrabal S, Valero ML, Cimas FJ, Serrano-Oviedo L, Villas MV, Romero-Fernandez J, Nunez MI, Sanchez-Prieto R. Abrogation of the p38 MAPK alpha signaling pathway does not promote radioresistance but its activity is required for 5-Fluorouracil-associated radiosensitivity. Cancer Lett. 2013;335:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]