Abstract

Background

Induction of labour is the artificial initiation of labour in a pregnant woman after the age of fetal viability but without any objective evidence of active phase labour and with intact fetal membranes. The need for induction of labour may arise due to a problem in the mother, her fetus or both, and the procedure may be carried out at or before term. Obstetricians have long known that for this to be successful, it is important that the uterine cervix (the neck of the womb) has favourable characteristics in terms of readiness to go into the labour state.

Objectives

To compare Bishop score with any other method for assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening in women admitted for induction of labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (31 March 2015) and reference lists of retrieved studies to identify randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Selection criteria

All RCTs comparing Bishop score with any other methods of pre‐induction cervical assessment in women admitted for induction of labour. Cluster‐RCTs were eligible for inclusion but none were identified. Quasi‐RCTs and studies using a cross‐over design were not eligible for inclusion. Studies published in abstract form were eligible for inclusion if they provided sufficient information.

Comparisons could include the following. 1. Bishop score versus transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS). 2. Bishop score versus Insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐1 (IGFBP‐1). 3. Bishop score versus vaginal fetal fibronectin (fFN). However, we only identified data for a comparison of Bishop score versus TVUS.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the trials for inclusion, extracted the data and assessed trial quality. Data were checked for accuracy.

Main results

We included two trials that recruited a total of 234 women. The overall risk of bias was low for the two studies. Both studies compared Bishop score withTVUS.

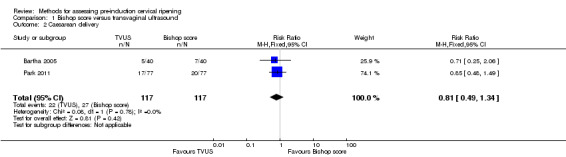

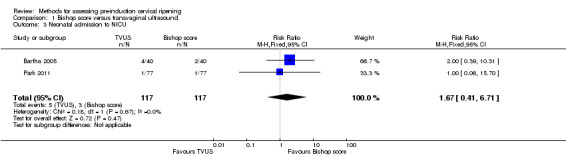

The two included studies did not show any clear difference between the Bishop score and TVUS groups for the following main outcomes: vaginal birth (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.25, moderate quality evidence), caesarean delivery (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.34, moderate quality evidence), neonatal admission into neonatal intensive care unit (RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.41 to 6.71, moderate quality evidence). Both studies only provided median data in relation to induction‐delivery interval and reported no clear difference between the Bishop and TVUS groups. Perinatal mortality was not reported in the included studies.

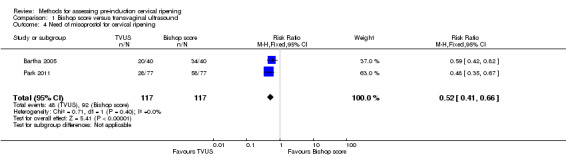

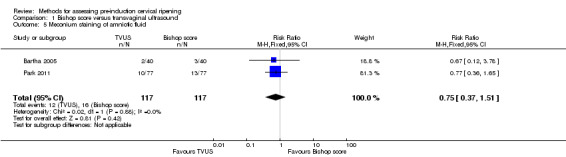

For the review's secondary outcomes, the need for misoprostol for cervical ripening was more frequent in the TVUS group compared to the Bishop score group (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.66, two studies, 234 women, moderate quality evidence). In contrast, there were no clear differences between the Bishop scope and TVUS groups in terms of meconium staining of the amniotic fluid, fetal heart rate abnormality in labour, and Apgar score less than seven. Only one trial reported median data on the induction‐delivery interval and induction to active phase interval, the trialist reported no difference between the Bishop group and the TVUS group for this outcome. Neither of the included studies reported on uterine rupture.

Authors' conclusions

Moderate quality evidence from two small RCTs involving 234 women that compared two different methods for assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening (Bishop score and TVUS) did not demonstrate superiority of one method over the other in terms of the main outcomes assessed in this review. We did not identify any data relating to perinatal mortality. Whilst use of TVUS was associated with an increased need for misoprostol for cervical ripening, both methods could be complementary.

The choice of a particular method of assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening may differ depending on the environment and need where one is practicing since some methods (i.e. TVUS) may not be readily available and affordable in resource‐poor settings where the sequelae of labour and its management is prevalent.

The evidence in this review is based on two studies that enrolled a small number of women and there is insufficient evidence to support the use of TVUS over the standard digital vaginal assessment in pre‐induction cervical ripening. Further adequately powered RCTs involving TVUS and the Bishop score and including other methods of pre‐induction cervical ripening assessment are warranted. Such studies need to address uterine rupture, perinatal mortality, optimal cut‐off value of the cervical length and Bishop score to classify women as having favourable or unfavourable cervices and cost should be included as an outcome.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Cervical Ripening; Labor, Induced; Cervix Uteri; Cervix Uteri/diagnostic imaging; Cervix Uteri/physiology; Cesarean Section; Delivery, Obstetric; Hospitalization; Intensive Care Units, Neonatal; Misoprostol; Oxytocics; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Ultrasonography

Plain language summary

Methods for assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening, the ability of the cervix to open in response to spontaneous uterine contractions

In this review, researchers from The Cochrane Collaboration examined a comparison between the Bishop score and any other method for checking pre‐induction cervical ripening in women admitted for induction of labour. The Bishop score is the traditional method of determining the readiness of the cervix to open (dilate) before labour induction. It also assesses the position, softening and shortening of the cervix, and the location of the presenting part of the baby. After searching for relevant trials up to 31 March 2015, we included two randomised controlled trials that recruited 234 pregnant women.

What are the methods for pre‐induction softening of the neck of womb and why is it important to soften the neck of womb before induction of labour?

Induction of labour is the non‐natural process of starting labour in a pregnant woman after the age the baby is more likely to survive following delivery, when there is no clear evidence of serious onset of labour and the membranes covering the baby are unruptured. Induction of labour may be needed because of a problem in the mother, or her baby or both, and is carried out at or before the ninth (last) month of pregnancy. Obstetricians (specialist caring for pregnant women) have long known that for this to be successful, it is important that the uterine cervix (the neck of the womb) has the favourable characteristics that make it ready to go into the labour. The delivery method and total duration of labour are affected by many factors and cervical readiness (ripeness) is just one of these.

What the research says

Moderate quality evidence was available from the two included studies which compared the Bishop score with transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) (ultrasound done through the vagina). The studies were considered to be at a low risk of bias. The need for misoprostol (a drug) for softening the cervix (cervical ripening) was more common in the TVUS arm. No clear difference was seen between the two methods in terms of vaginal birth, caesarean delivery, admission of the newborn into the neonatal intensive care unit, meconium staining of the amniotic fluid, abnormal heart beat of the baby within the womb whilst the mother was in labour and Apgar score less than seven (difficulty of the baby establishing life and other life movements on its own immediately after childbirth). None of the included studies reported on tears of the womb or death of the baby just before, during or immediately after childbirth. We did not find any studies that compared Bishop score with any other methods such as the presence of vaginal fetal fibronectin or insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐1.

Authors conclusions

Although the overall quality of evidence is moderate, there is no difference in outcomes between the two methods (Bishop score and TVUS) apart from the increased need of misoprostol in the TVUS group. Both methods could be useful to each other, or complementary as the Bishop score does not need any special equipment and uses digital examination which is required to induce labour (to insert a cervical ripening agent, rupture the membranes or separate them from the cervix) but TVUS can give additional information that may affect the course and management of the labour. The choice of a particular method may differ depending on the environment and need since TVUS requires training and may not be readily available and affordable in resource‐poor countries.

Future research The two included studies involved a small number of women and further studies are needed. Such studies should include outcomes such as rupture of the womb, perinatal mortality, most appropriate cut‐off value for the cervical length and Bishop score to classify women as having ripe or unripe cervices, and cost.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Bishop score compared with transvaginal ultrasound for assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening.

| Bishop score compared with transvaginal ultrasound for assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with singleton cephalic fetuses undergoing assessment for pre‐induction cervical ripening. Settings: hospital labour ward. Intervention: Bishop score. Comparison: transvaginal ultrasound. | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Transvaginal ultrasound | Bishop score | |||||

| Vaginal birth | 701 per 1000 | 736 per 1000 (645 to 841) | RR 1.05 (0.92 to 1.2) | 234 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Caesarean delivery | 231 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (115 to 312) | RR 0.82 (0.5 to 1.35) | 234 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Neonatal admission to NICU | 26 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 (11 to 175) | RR 1.67 (0.41 to 6.83) | 234 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Need of misoprostol for cervical ripening | 786 per 1000 | 417 per 1000 (330 to 527) | RR 0.53 (0.42 to 0.67) | 234 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Meconium staining of amniotic fluid | 137 per 1000 | 103 per 1000 (51 to 206) | RR 0.75 (0.37 to 1.51) | 234 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Apgar score at 5 minutes less than 7 | 17 per 1000 | 11 per 1000 (1 to 85) | RR 0.62 (0.08 to 4.99) | 234 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Fetal heart rate abnormality in labour | 39 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (8 to 187) | RR 1 (0.21 to 4.8) | 154 (1) | See comment2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The total number of events is less than 300

2 Grade assessment was not done for this outcome because only one trial reported it.

Background

Induction of labour is the artificial initiation of labour in a pregnant woman after the age of fetal viability but without any objective evidence of active phase labour and with intact fetal membranes (Lawani 2014). This procedure is increasingly being carried out in obstetric units for varying indications (Baacke 2006; Crane 2006). The need for induction of labour may arise due to a problem in the mother, her fetus or both, and the procedure may be carried out at or before term. Obstetricians have long known that for this to be successful, it is important that the uterine cervix (the neck of the womb) has favourable characteristics in terms of readiness to go into the labour state (Baacke 2006; Edwards 2000). However, some other factors may also affect the success of labour induction (Hou 2012). The definition of failed induction of labour has controversies surrounding it (Rouse 2011), but the risks are clear. Because of the risks of failed induction of labour, a variety of maternal and fetal factors as well as screening tests have been suggested to predict labour induction success (Crane 2006). These include certain maternal factors such as parity (the number of times a woman has delivered), height, weight, body mass index (BMI), maternal age, Bishop score and its individual components, fetal factors such as birthweight and gestational age, transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) assessment of the cervix, and biochemical markers including fetal fibronectin (fFN) and insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐1 (IGFBP‐1).

Description of the condition

During pregnancy, the cervix is a solid and closed organ. As the pregnancy advances towards the time of labour, the cervix undergoes some stages of remodelling in readiness for delivery (Timmons 2010). The first phase of the remodelling is the stage of softening which involves a decline in the tissue tensile strength and this may start in the first trimester (the first 13 weeks of pregnancy). This first stage is usually slow but progressive and requires the progesterone‐rich environment to take place. In the weeks preceding spontaneous labour and delivery, the next stage of cervical ripening commences (Timmons 2010; Word 2007). It is only after the cervix has ripened that it can dilate in response to spontaneous uterine contractions. The process of cervical ripening is a complex one that is associated with an increase in the concentration of the hydrophilic (water attracting) glycosaminoglycans and non collagenous proteins (Leppert 1995; Word 2007). This phase of cervical remodelling is therefore very important as this is what gives the cervix the ability to dilate (open up) in response to uterine contractions of labour. It is not very clear what the role of chemicals such as prostaglandins is in the natural ripening process but it is known that administration of prostaglandins or their analogues will lead to ripening of the cervix in a woman with an unripe cervix. Some studies have also shown that the histological features of a naturally ripened cervix are similar to that induced by exogenous prostaglandins (Rath 1993; Uldbjerg 1983; Word 2007). Although induction of labour is an artificial procedure, it tries to, as much as possible, to mimic the physiological process. Therefore, to expect a successful induction of labour, care should be taken to determine if the cervix is ripe. For the unripe cervix, certain agents should be used to ripen the cervix in order to optimise the success of labour induction.

Description of the intervention

Several methods have been used to assess the ripeness of the cervix prior to labour induction and newer methods are being sought. The traditional method is the cervical scoring system described by Bishop, known as the Bishop score (Bishop 1964). This system assesses the position, consistency, effacement (shortening of the cervix), dilatation of the maternal cervix, as well as the station of the fetal presenting part. The maximum score here is 13 and studies have shown that women with a score of nine or more were more likely to have successful labour induction (Baacke 2006). In his modification, Burnett discovered that women with a score of at least six achieved vaginal birth within six hours in 90% of the time, whereas, the course of labour was unpredictable in women with a score less than six (Baacke 2006; Burnett 1966). Some other studies have also considered a score of six or more as favourable for labour induction (Eggebo 2009). Although Bishop described his method to predict the success of labour induction in parous women with cephalic presentation, the system is used today for every proposed induction of labour (Baacke 2006). This original scoring system is simple to perform but several questions have arisen concerning its ability to objectively assess cervical ripening prior to labour induction and so several modifications of the system have been proposed (Baacke 2006; Burnett 1966; Eggebo 2009; Goldberg 1997; Keepanasseril 2012). Some studies have even shown that it is a poor predictor of the outcome of labour (Hendrix 1998). This has led researchers into searching for alternative methods that may be more objective.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) assessment of the cervix was subsequently introduced to assess pre‐induction cervical ripening (Keepanasseril 2007; Pandis 2001; Rane 2004; Rane 2005; Yang 2004). TVUS is able to measure objectively the cervical length, internal os diameter and the posterior angle. This method has been used to predict preterm delivery (Goldberg 1997) and has found a place in the assessment of pre‐induction cervical ripening (Crane 2006). Studies have compared the performance of the Bishop score and TVUS cervical assessment in the prediction of the outcome of labour induction and have given mixed results (Crane 2006; Eggebo 2009; Yang 2004). In some studies, TVUS cervical assessment proved superior to the Bishop score (Pandis 2001; Rane 2004), while in others superiority was not demonstrated (Rozenberg 2000; Rozenberg 2005).

Some chemicals related to pregnancy have also been studied for predicting the success of labour induction. Fetal fibronectin (fFN) is a glycoprotein that is found in the amniotic fluid and choriodecidual interface in high concentrations but leaks into the vaginal secretion prior to the onset of spontaneous labour (Baacke 2006; Mouw 1998; Roman 2004). In his study, Ahner et al noted that women who tested positive to fFN in their vaginal secretion were more likely to deliver within 24 hours (Ahner 1995). The same study also showed that women with both a low Bishop score and negative fFN test had the highest risk of prolonged labour and operative deliveries. Another study has compared the Bishop score and fFN testing and concluded that their performances were similar (Blanch 1996). Ekman et al also documented that a positive vaginal fFN correlated well with cervical ripeness but recommended a quantitative study to determine the threshold value that can be a cut‐off point for ripeness (Ekman 1995). Another chemical that has been evaluated is Insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐1 (IGFBP‐1). It exists in different parts of the body as isoforms depending on its phosphorylation status. The amniotic fluid contains mainly the non phosphorylated isoform while the decidual tissues contain the phosphorylated isoform (Martina 1997; Westwood 1994). Nuutila and his group have evaluated IGFBP‐1 to see if its presence in cervical secretion reflects the ripeness of the cervix (Nuutila 1999).

How the intervention might work

The physiologic cervical ripening that predates spontaneous uterine contractions is associated with effacement, opening of the internal cervical os (dilatation) and softening of the cervix (consistency). To be able to assign a Bishop score, a vaginal examination is performed to assess the state of the cervix in terms of its consistency, dilatation, position and effacement as well as the station of the fetal presenting part. Scores are assigned to each parameter and the total score becomes the Bishop score. The higher the score, the more the cervix is ripe and therefore, successful induction of labour is expected. Harrison et al did show that up to 87% of women with a Bishop score of at least seven will deliver within nine hours, whereas only 44% of those with score of four or less will deliver within the same time frame (Harrison 1977). It may be difficult to fully assess the cervical length especially when the internal os is closed as the finger may not reach the part of the cervix beyond the vaginal fornices (Crane 2006). TVUS is able to measure the cervical length and cervical funnelling (representing dilatation), which are changes associated with cervical ripening (Baacke 2006). TVUS is also able to measure the posterior cervical angle and studies have shown that a value of more than 90 degrees predicts successful vaginal birth (Eggebo 2009; Rane 2004). In another study, cervical length assessment by TVUS predicted successful induction of labour (Yang 2004).

Fetal fibronectin exists in the choriodecidual space and the amniotic fluid and its production increases with advancing gestational age. Uterine activity leads to its leakage into the cervico‐vaginal secretion even with an intact fetal membrane (Mouw 1998; Ojutiku 2002). It has been suggested that this leakage precedes the onset of labour by about two weeks and may represent the later stages of physiological events before the onset of labour (Garite 1996). Therefore, its detection in the cervico‐vaginal secretion may suggest imminent labour. Ahner et al did show that women with intact fetal membrane undergoing induction of labour were more likely to deliver within 24 hours if they had positive fFN (Ahner 1995). IGFBP‐1 exists as the phosphorylated isoform in the choridecidual space and leaks into the cervix and vagina with increasing choriodecidual activity (Martina 1997; Westwood 1994). Its role in the prediction of preterm birth has been assessed by different authors. One study assessed it among symptomatic women and documented a positive predictive and negative predictive values of 24% and 86% respectively for delivery before 37 weeks (Cooper 2012). in another study, the positive and negative predictive value for preterm delivery before 35 weeks were 47% and 93% respectively (Elizur 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

Obstetricians, over the years, have known that the pre‐induction cervical status is an important determinant of the outcome of induction of labour. Despite the different modifications, the Bishop score remains the most popular way of assessing the cervix for ripeness but its objectivity and ability to predict vaginal delivery have been contested (Baacke 2006). Currently, there is no strong evidence to suggest the most dependable method for assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening since different studies give inconsistent findings (Pandis 2001; Park 2007; Rane 2003;Tan 2007). If such evidence becomes available, clinicians will be guided appropriately in order to optimise the outcome of labour induction.

Objectives

To compare different methods of pre‐induction cervical assessment for women admitted for induction of labour.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised control trials that compared Bishop score with any other methods of pre‐induction cervical assessment in women admitted for induction of labour. We planned to include cluster‐randomised trials but our search did not find any. Quasi‐RCTs and studies using a cross‐over design were not eligible for inclusion. We found one relevant abstract but it did not contain sufficient information for data extraction. We contacted the trial authors for further details but they did not respond so we excluded the study.

Types of participants

Pregnant women with live singleton foetuses in cephalic presentation admitted for induction of labour at term.

Types of interventions

Trials comparing Bishop score with any one or more other methods of assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening (e.g. transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS), insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐1 (IGFBP‐1) and vaginal fetal fibronectin (fFN)).

Bishop score versus TVUS.

Bishop score versus IGFBP‐1.

Bishop score versus vaginal fFN.

The two trials included compared Bishop score and TVUS.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Induction‐delivery interval.

Vaginal birth.

Caesarean delivery.

Neonatal admission into neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Perinatal mortality.

Secondary outcomes

Interval from induction to active phase labour.

Need for other cervical ripening agent.

Meconium staining of the amniotic fluid.

Fetal heart rate abnormality in labour.

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes.

Uterine rupture.

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (31 March 2015).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We also reviewed citations and references from identified studies for relevant publications as well as contacted experts, trialists and authors for unpublished and ongoing trials.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection and analysis was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed the eligibility and methodological quality of all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy, without consideration of trial results. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, consulted a third author.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently applied the inclusion criteria to potentially relevant trials with a pre‐designed and validated data extraction form. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or by consulting a third author. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked them for accuracy. When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we contacted authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor. We did not find any cluster‐randomised trials.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we described the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we described the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

For each included study, we described the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

For each included study, we described the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

For each included study, we described and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

For each included study, we described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

For each included study, we described any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we consider it was likely to impact on the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we planned to use the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis is the individual respondent in the included trials.

Dealing with missing data

There were no missing data in the included trials. Both trials analysed their data on an intention‐to‐treat basis. The two trials reported their continuous data as median and interquartile ranges. We contacted the authors for details on mean values or the range but they did not respond. We, therefore, could not do a meta‐analysis for those outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² was greater than 30% and either the T² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates of this review, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it is reasonable to assume that studies are estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials are examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods are judged sufficiently similar. In future updates of this review, if there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity is detected, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary will be treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials.

If we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not identify substantial heterogeneity in our analyses. However, in future updates, if we identify substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We will consider whether an overall summary is meaningful, and if it is, use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We will carry out the following subgroup analyses as prespecified in our protocol.

Women who have not delivered any baby previously (nulliparous women) versus those who have delivered previously.

Induction of labour carried out at a gestational age less than 37 completed weeks versus those conducted at 37 completed weeks or more (i.e. preterm versus term).

Subgroup analysis will be restricted to the primary outcomes.

We will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the χ² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not carry out planned sensitivity analysis because the two included trials were rated as 'low risk of bias'. In future updates, we will carry out sensitivity analysis to explore the effects of trial quality assessed by allocation concealment and other risk of bias components, by omitting studies rated as ’high risk of bias’ for these components. We will restrict this to the primary outcomes We will compare meta‐analyses of trials in which the unit of randomisation was at the individual level compared with those at the cluster level.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

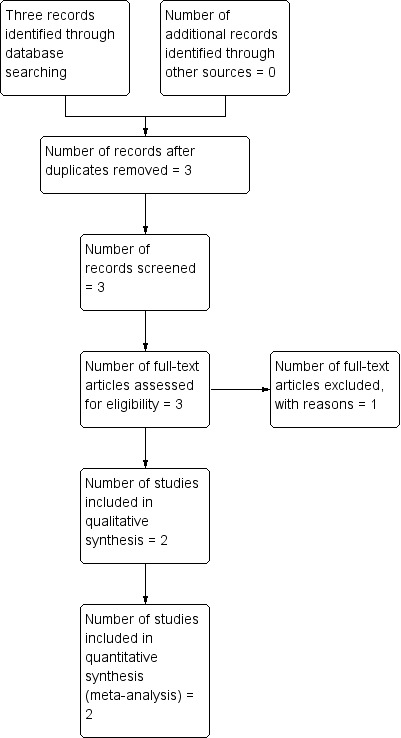

See: Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

The search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register retrieved three reports (see Figure 1). We searched other sources but did not find any other trials. Two studies are included (Bartha 2005; Park 2011) and one has been excluded (Ryu 2013).

Included studies

We included two trials (Bartha 2005; Park 2011) involving 234 women.

Design

Both trials were randomised controlled trials.

Sample size

Bartha 2005 recruited 80 women and randomised 40 of them into each arm while Park 2011 recruited 154 women with 77 in each arm.

Setting

One trial (Bartha 2005) was conducted at the University Hospital of Puerto Real, Cadiz, Spain. The other trial (Park 2011) was conducted at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (Seongnamsi, Korea).

Participants

Participants in both trials were women admitted for induction of labour at term and who were carrying life singletons in cephalic presentation and had intact membranes.

Interventions

The intervention compared in both trials were the Bishop score and trans vaginal ultrasonography (TVUS).

Outcomes

The outcomes for one trial (Bartha 2005) were use of prostaglandin for cervical ripening, interval from induction to any type of delivery, interval from induction to vaginal delivery, need for oxytocin augmentation, interval from induction to active phase labour, number of women with a Bishop score of at least six at six hours from start of induction, number of women with spontaneous rupture of membranes and the interval from start of induction to this event, route of delivery, number of women with caesarean section for failed induction, meconium passage, birthweight, Apgar scores and number of infants admitted to neonatal intensive care unit.

The outcomes for the other trial (Park 2011) were need for prostaglandin, need for oxytocin induction, interval to active phase, induction delivery interval, vaginal delivery within 24 hours, rate of caesarean section.

Excluded studies

We excluded one trial (Ryu 2013) from the review. This was only published in abstract form and did not provide sufficient information. We contacted the trial authors but did not receive a reply.

Risk of bias in included studies

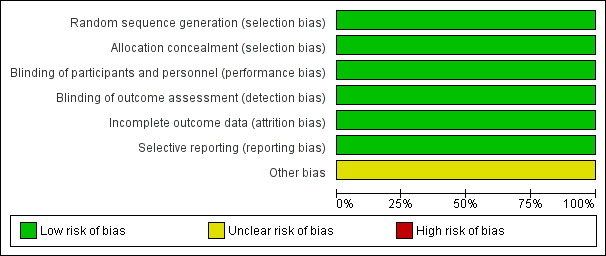

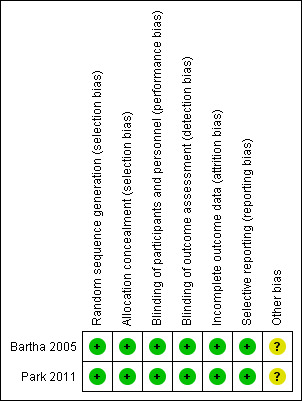

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Both included trials were considered 'low risk of bias' for almost all domains of risk of bias.

Allocation

Both trials were randomised trials and used computer‐generated random numbers (low risk of bias). One study (Park 2011) randomised in blocks of four. In both studies, allocation concealment was achieved by using sequentially numbered, sealed opaque envelopes (low risk of bias).

Blinding

The participants, personnel and outcome assessors were all blinded to the intervention (rated as low risk of bias for both performance and detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data

There was no attrition in one study (Bartha 2005) while six participants were dropped in one study (Park 2011) but both studies conducted the analysis as per intention‐to‐treat (both assessed as low risk of bias).

Selective reporting

There was no evidence of selective reporting as the trial authors reported all their proposed outcomes (low risk of bias).

Other potential sources of bias

No other source of bias was identified.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See: Table 1.

We did not identify any studies that compared Bishop score with either IGFBP‐1 or versus vaginal fetal fibronectin (fFN).

The two included studies compared Bishop score versus TVUS.

Bishop score versus transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) ‐ comparison 1

Primary outcomes

Induction‐delivery interval

Both of the included studies provided median data for this outcome (data not added to data and analysis tables). In one trial (Bartha 2005) the median induction‐delivery interval was reported to be 11.2 hours with an interquartile range 7.8 to 15.9 hours in the Bishop score arm. This was longer, though not significantly, than 9.5 hours (5.6 to 14.7) in the TVUS arm. In the second trial (Park 2011) the median induction‐delivery interval was reported to be 10.3 hours with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 7.0 to 13.5 in the Bishop score arm. This was slightly shorter, though not significantly, than the median duration of 10.9 hours (95% CI 9.4 to 12.3) in the TVUS arm.

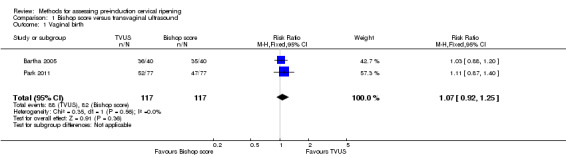

Vaginal birth

Both included trials reported on vaginal birth. Meta‐analysis showed that vaginal birth was more frequent in the group of women that were assessed using the Bishop score (although this difference was not statistically significant) (risk ratio (RR) 1.07, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.25, moderate quality evidence (Analysis 1.1)).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bishop score versus transvaginal ultrasound, Outcome 1 Vaginal birth.

Caesarean delivery

The two trials reported caesarean delivery. Meta‐analysis showed that caesarean delivery was more frequent in the trial arm assessed with TVUS although the difference did not reach a statistical significance ((RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.34, moderate quality evidence (Analysis 1.2)).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bishop score versus transvaginal ultrasound, Outcome 2 Caesarean delivery.

Neonatal admission to NICU

Both trials reported neonatal admission to NICU. Meta‐analysis showed that admission into NICU was more common in the arm assessed with the Bishop score but it did not reach a statistically significant level and the CI is wide ((RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.41 to 6.71, moderate quality evidence (Analysis 1.3)).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bishop score versus transvaginal ultrasound, Outcome 3 Neonatal admission to NICU.

Perinatal mortality

None of the trials reported on perinatal mortality.

Secondary outcomes

Interval from induction to active phase labour

Both of the included studies provided median data for this outcome (data not added to data and analysis tables). In one trial (Bartha 2005), the median interval from induction to active phase labour was 7.1 hours with an interquartile range of 5.1 to 9.9 in the Bishop score arm. This is longer, though not significantly, than 5.7 hours (3.0 to 10.5) in the TVUS arm. In the other trial (Park 2011), the interval from induction to active phase labour was 4.8 + 2.8 hours in the Bishop score arm. This was shorter than 5.7 + 3.4 hours in the TVUS arm.

Need for other cervical ripening agents

The need for misoprostol for cervical ripening was more frequent in the group of women who were assessed with TVUS and it reached a statistically significant level with a narrow confidence intervals ((RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.66, moderate quality evidence (Analysis 1.4). Apart from misoprostol, no other cervical ripening agent was reported by either of the trials.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bishop score versus transvaginal ultrasound, Outcome 4 Need of misoprostol for cervical ripening.

Meconium staining of the amniotic fluid

Meconium stained amniotic fluid was more common among those assessed with TVUS but it did not reach statistical significance ((RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.51, moderate quality evidence (Analysis 1.5)).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bishop score versus transvaginal ultrasound, Outcome 5 Meconium staining of amniotic fluid.

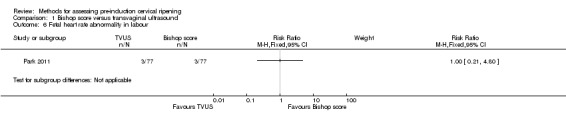

Fetal heart rate abnormality in labour

Only one trial (Park 2011) reported this outcome. Fetal heart rate abnormality in labour was similar in both arms (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.21 to 4.80 (Analysis 1.6)).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bishop score versus transvaginal ultrasound, Outcome 6 Fetal heart rate abnormality in labour.

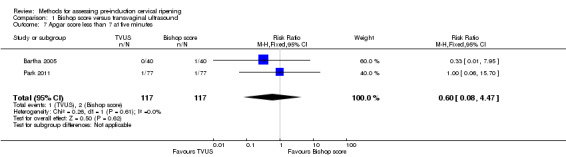

Apgar score at five minutes less than seven

Apgar score less than seven was more frequent among the group of women who were assessed with TVUS, but this result was not statistically significant ((RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.08 to 4.47, moderate quality evidence (Analysis 1.7)).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bishop score versus transvaginal ultrasound, Outcome 7 Apgar score less than 7 at five minutes.

Uterine rupture

Neither of the included trials reported on uterine rupture.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The routine methods of predicting whether an induced labour will result in successful vaginal delivery are based on the pre‐induction "favourability" of the cervix. Cervical assessment before induction of labour is important to determine the most appropriate method of induction.

In this review, we included two randomised controlled trials involving 234 women with singleton gestations that compared the use of the Bishop score with transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS). The two trials were considered to be at a low risk of bias and the overall quality of the evidence is moderate because of the small number of women randomised.

There were no clear differences between the two groups in terms of our primary outcomes: vaginal birth, caesarean delivery, and neonatal admission into neonatal intensive care unit. The induction‐delivery interval (which was only reported as median data) was found to be no different between the two groups. None of the included studies reported rates of perinatal mortality.

For our secondary outcomes, use of TVUS for cervical assessment was associated with a reduction in the use of misoprostol compared to the group of women assessed using the Bishop score. There were no clear differences identified for meconium stained amniotic fluid, fetal heart rate abnormality or Apgar score less than seven minutes. None of the included trials reported a difference in the interval from induction to active phase (median data reported). No data were identified for uterine rupture.

Although the overall quality of evidence in this review is moderate, as only 234 women were randomised in the two included studies, these data are insufficient for us to reach any meaningful conclusions about any advantages or disadvantages of using the Bishop score or TVUS for assessing the favourability of the cervix prior to induction of labour. We did not identify any studies that used other methods (i.e. IGFBP‐1 or vaginal fetal fibronectin (fFN)).

The question of whether using a particular method of assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening actually does more harm than good remains unanswered and this topic area deserves further study.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Although the overall quality of evidence is moderate, given the limited number of trials, the overall numbers of participants are small, and subgroup effects were difficult to assess with adequate power, which is a weakness of this meta‐analysis. Neither of the included trials was adequately powered to detect clinically important differences in outcomes.

Whilst the two randomised controlled studies (Bartha 2005; Park 2011) compared the various effects on the use of the two methods for pre‐induction cervical status scoring, Bartha 2005, examined the TVUS or Bishop score for pre‐induction cervical assessment to choose which induction agent significantly reduces the need for intracervical prostaglandin treatment without adversely affecting the success of induction using a Bishop score of less than six as the cut‐off. In contrast, Park 2011, used a Bishop score ≤ four as cut‐off for defining the unfavourability of the cervix. However, it should be noted that these results were based on defining an unfavourable cervix using as the cut‐off values a Bishop score of ≤ four and a cervical length of at least 28 mm; obviously, the use of different cut‐off values to define an unfavourable cervix can yield different findings because they are dependent upon the cut‐off values used.

Arbitrarily defined cervical length cut‐off values for the definition of an unfavourable cervix that do not represent established clinical criteria are likely to increase subjective bias, although a defined cut‐off value was stated in each trial included in this review. Another limitation is that the induction of labour protocol may have differed in each of the included trials, because this may influence the outcome of induction, and the results may thus not apply if other ancillary methods such as serial membrane sweeping/stripping and or amniotomy is routine in the trial centres involved in the study. This is because of the two trials included in this review, the authors of Park 2011 recruited only nulliparous women while Bartha 2005 recruited both nulliparous and parous women. However, the delivery mode and total duration of labour can be affected by many factors other than cervical status, such as parity or indications for caesarean delivery (Yang 2004). An additional limitation is the lack of data on uterine rupture, an important outcome to consider when implementing any peripartum intervention, regardless of the method of this intervention in the included studies. Thus far, however, despite the small numbers and potential biases in this analysis, there does not appear to be a difference in the interval to vaginal delivery, neonatal admission to NICU or the rate of caesarean section. More evidence needs to be obtained through properly conducted randomised controlled trials to further address this clinical question.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE methodology, and the basis for the judgements is presented in the Table 1 (Summary of findings for the main comparison). The overall quality of evidence for comparing Bishop score and TVUS for assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening can be described as moderate quality. We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level on account of instability of results since there are fewer than 200 events per arm. Larger trials are needed to have full confidence in these effects.

Potential biases in the review process

A comprehensive search was performed, including a thorough search of the grey literature and all studies were independently sifted and had data extracted by two review authors. We were not very restrictive in our inclusion criteria with regard to types of studies as we planned to include cluster‐randomised studies even though we excluded quasi‐randomised studies. Overall, no potential biases in the review process were identified.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

One prior systematic review and meta‐analysis of prospective observational studies has been published (Hatfield 2007) on sonographic cervical assessment to predict the success of labour induction.Hatfield 2007 excluded trials if they contained data presented in later articles or did not contain extractable data. They also included studies with very low methodological quality and so the total analysis included 20 trials with 3101 aggregate participants.The results of the Hatfield 2007 review showed that cervical length predicted successful induction (likelihood ratio (LR) of positive test 1.66; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.20 to 2.31) and failed induction (LR of negative test 0.51; 95% CI 0.39 to 0.67), but did not predict any specific outcome (e.g. mode of delivery). Hatfield 2007 concluded that sonographic cervical length was not an effective predictor of successful labour induction and therefore further evaluation of cervical wedging in the prediction of labour induction is warranted.

Another meta‐analysis (Crane 2006) of prospective observational (cohort) studies identified from MEDLINE, PubMed, and EMBASE and published from 1990 to October 2005 evaluated the use of TVUS and fetal fibronectin (fFN) in predicting the success of induction of labour in women at term with singleton gestations. Both TVUS and Bishop score predicted successful induction (LR 1.82; 95% CI 1.51 to 2.20 and LR 2.10; 95% CI 1.67 to 2.64, respectively). In addition, fFN and the Bishop score predicted successful induction (LR 1.49; 95% CI 1.20 to 1.85, and LR 2.62; 95% CI 1.88 to 3.64, respectively). Although TVUS and fFN predicted successful labour induction, neither was shown to be superior to Bishop score.

Apart from the Hatfield 2007 and Crane 2006 reviews, no other systematic review or meta‐analysis on the methods for assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening in term parturients has been previously published. Crane 2008 was a systematic review to estimate the ability of cervical length measured by TVUS in asymptomatic high‐risk women to predict spontaneous preterm birth. Although Crane 2008 used similar keywords as the present review: 'transvaginal ultrasonography' or ('cervix' and ('ultrasound' or 'ultrasonography' or 'sonography')); and ('delivery' or 'labour/labor' or 'birth'), they identified cohort studies evaluating transvaginal ultrasonographic cervical length measurement in predicting preterm birth (not term pregnancies) in asymptomatic women who were considered at increased risk (because of a history of spontaneous preterm birth, uterine anomalies or excisional cervical procedures), with intact membranes and singleton gestations.

Two non‐systematic reviews of observational studies (Baacke 2006; Edwards 2000) evaluated the usefulness of cervical ultrasound and testing for the presence of fFN (Baacke 2006) in comparison with Bishop score in assessing cervical readiness for labour induction, but the authors of Baacke 2006 concluded that neither of the methods provides a significant improvement over digital examination. Therefore, convincing evidence that this technique provides significant additional information when compared to digital examination is lacking. Edwards 2000 and Baacke 2006 added that the Bishop score, being the most widely used digital examination scoring system, is still the most cost effective and accurate method of evaluating the cervix before labour induction.

In a similar vein, the authors of Meijer‐Hoogeveen 2009, a prospective observational study, examined the predictive value of cervical length as measured by TVUS in supine and upright maternal positions for the mode of delivery and induction‐to‐delivery interval after induction of labour at term, and comparing these measurements with the Bishop score and its predictive value. In a logistic regression analysis Meijer‐Hoogeveen 2009 revealed that in nulliparous women, only the cervical length measured in the upright position was a significant predictor of the need for caesarean section (odds ratio 1.14; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.27). However, only the Bishop score correlated significantly with the induction‐to‐delivery interval in both nulliparous and parous women. The authors of Meijer‐Hoogeveen 2009 concluded that maternal postural change could improve the accuracy of sonographically‐measured cervical length for predicting a successful vaginal delivery following induction of labour at term.

However, it is not clear which cut‐off value of sonographically measured cervical length is most likely to indicate benefit from a cervical ripening agent prior to induction of labour when compared with the traditional Bishop score method (Bishop 1964). These studies, given the low numbers of participants and non‐randomised/observational nature of the studies, need to be interpreted with caution.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Fortuitously, the merit of the Bishop score is that it can clinically elucidate parameters such as consistency and position of the cervix or station of the presenting part that may influence the labour management and outcome. However, these can painstakingly be assessed by transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS). Additionally, in assessing the Bishop score, no special equipment is required and digital vaginal assessment has become an integral part of induction of labour. This is because it is required to place the pre‐induction cervical ripening agent in the vagina or cervix, and to perform amniotomy or membrane sweeping. Therefore, a Bishop score could usually be obtained within this context. Nevertheless, TVUS is thought to be less subjective compared with the Bishop score. Transvaginal ultrasound may give additional information that cannot be clinically determined by Bishop scores, which may affect the course and management of the parturients and so it can effectively be used to make clinical decisions before induction of labour is embarked on. This review has shown that there is insufficient evidence to support the use of TVUS over standard digital vaginal assessment in pre‐induction cervical ripening. There is therefore not enough evidence from this review to suggest a change of practice. Practitioners may determine their practice based on the environment and both methods can be applied together as they may complement each other.

Implications for research.

Due to the limitations of the small number of women studied, further adequately powered randomised controlled trials involving TVUS and Bishop score for assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening among parturients are needed. It would seem that from the meta‐analysis of the two included trials, we could not categorically conclude that TVUS is superior to the Bishop score in pre‐induction cervical assessment. Perhaps the cut‐off point to consider a cervix as being unripe should be more restricted than below six, which is commonly used in clinical practice. Future prospective randomised controlled trials involving other methods of pre‐induction cervical ripening assessment methods are needed. To our knowledge, direct comparisons between Bishop score and other modalities (e.g. insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐1 (IGFBP‐1) and vaginal fetal fibronectin (fFN)) for assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening among parturients has yet to be carried out. Future studies also need to address uterine rupture, perinatal mortality, optimal cut‐off value of the cervical length and Bishop score to classify women as having favourable or unfavourable cervices and cost should be included as an outcome.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Nigerian branch of the South African Cochrane Centre for training us on the methods for writing a systematic review.

Ifeanyichukwu U Ezebialu (IUE) and George U Eleje (GUE) were awarded a fellowship by the South African Cochrane Centre through a grant received from the Effective Health Care Research Consortium www.evidence4health.org, which is funded by UKaid from the UK Government for International Development. While GUE acknowledges the Faculty of Medicine, College of Health Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi Campus, Nigeria, IUE specially acknowledges College of Medicine, Anambra State University Amaku, Awka, Nigeria for providing the enabling environment for staff development that enabled them to attend the Fellowship Course in South Africa. We are also grateful to Prof GJ Hofmeyr of Effective Care Research Unit, East London Hospital Complex, East London, South Africa for training some of the authors in Cochrane Systematic Reviews.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by two peers (an editor and referee who is external to the editorial team), members of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Bishop score versus transvaginal ultrasound.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal birth | 2 | 234 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.92, 1.25] |

| 2 Caesarean delivery | 2 | 234 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.49, 1.34] |

| 3 Neonatal admission to NICU | 2 | 234 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.41, 6.71] |

| 4 Need of misoprostol for cervical ripening | 2 | 234 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.41, 0.66] |

| 5 Meconium staining of amniotic fluid | 2 | 234 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.37, 1.51] |

| 6 Fetal heart rate abnormality in labour | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7 Apgar score less than 7 at five minutes | 2 | 234 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.6 [0.08, 4.47] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bartha 2005.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Used computer‐generated random numbers to randomise. The participants allocation was concealed by serially numbered opaque envelopes. | |

| Participants | 80 women admitted for induction of labour at the University Hospital of Puerto Real, Cadiz, Spain, who were carrying singleton fetuses in cephalic presentation. From May 2001 to March 2002. Exclusion criteria were non vertex presentation, uterine scars other than prior low transverse caesarean scar, multiple gestation and premature rupture of membranes. | |

| Interventions | Bishop score, transvaginal ultrasound. | |

| Outcomes | Use of prostaglandin for cervical ripening, interval from induction to any type of delivery, interval from induction to vaginal delivery, need for oxytocin augmentation, interval from induction to active phase labour, number of women with Bishop of at least 6 at 6 hours from start of induction, number of women with spontaneous rupture of membranes and interval from start of induction to this event, route of delivery, number of women with caesarean section for failed induction, meconium passage, birthweight, Apgar scores and number of infants admitted to neonatal intensive care unit. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | This was adequately done. "Subjects who gave informed consent were assigned by a computerized random number generator...." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Concealment was adequate. "Assignments were concealed by sequentially numbered opaque envelopes prepared by a medical student not involved in the clinical care of the subject." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinding of participants and personnel was adequate. "All women underwent cervical assessment by both Transvaginal ultrasound but a woman who was randomised to one method was treated on the basis of that method only." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | The outcome assessor was blinded. "...The person who assessed the cervix for clinical decision was blinded...." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Intention‐to‐treat analysis, there was no attrition. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All the proposed outcome measures were reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | It was not clear if there was any other source of bias. |

Park 2011.

| Methods | Prospective randomised trial conducted between November 2008 and August 2010. | |

| Participants | 154 nulliparous women carrying live singleton fetuses in cephalic presentation admitted for induction of labour at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (Seongnamsi, Korea). Inclusion criteria included nulliparity, singleton pregnancy, live fetus with vertex presentation, intact amniotic membranes, at least 37 weeks' gestation, absence of labour and no previous uterine surgical procedures. | |

| Interventions | Bishop score, transvaginal ultrasonography. | |

| Outcomes | Need for prostaglandin, need for oxytocin induction, interval to active phase, induction delivery interval, vaginal delivery within 24 hours, rate of caesarean section. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Random sequence generation was adequately generated. "Women agreeing to participate in the study were assigned...by means of computerised random number generator." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation concealment was adequate. "Group allocation was predetermined and placed in sequentially numbered, sealed opaque envelope...." |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Both participants and personnel were blinded. "Envelopes were prepared by a research nurse who was not involved in the clinical care." "...cervical examination by transvaginal ultrasound and digital clinical examination was performed by separate examiners, blinded to each other's results". "Group allocation was not revealed to the women or attending physician." |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | The outcome assessor was not aware of the interventions for each participant. "Group allocation was not revealed to the women or attending physician." |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Intention‐to‐treat analysis, low rate of attrition. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All proposed outcome measures were reported. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | It was not clear if there was any other source of bias. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ryu 2013 | The study was only an abstract and it did not contain sufficient information. The trial authors were contacted to provide more details but they did not respond. |

Differences between protocol and review

We would like to highlight the following differences between our published protocol (Ezebialu 2013) and the full review.

Methods/types of participants ‐ in our published protocol this section read 'Women who were admitted for induction of labour and are carrying singleton pregnancies in cephalic presentation at a gestational age of at least 24 completed weeks' ‐ we have changed this to read 'Pregnant women with live singleton foetuses in cephalic presentation admitted for induction of labour at term.'

Methods/secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome 'use of misoprostol or other agents for cervical ripening' has been replaced by 'need for other cervical ripening agent' because it was worded in the same way as it has been reported in a trial previously.

The secondary outcome 'fetal heart rate abnormality' has been replaced by 'fetal heart rate abnormality in labour' to specifically distinguish it from fetal heart rate abnormality prior to induction of labour.

The secondary outcome 'Apgar score less than seven' has been edited to read 'Apgar score less than seven at five minutes'.

Methods/Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity ‐ we have removed the planned subgroup analysis for 'Induction of labour for a live fetus versus induction for intrauterine fetal death'.

No other changes from the protocol were made.

Contributions of authors

Ifeanyichukwu U Ezebialu (IUE) and George U Eleje (GUE) identified and extracted data from eligible trials for this review. IUE entered data into Review Manager. IUE and GUE performed risk of bias assessment and analysed data. IUE, Ahizechukwu C Eke and Chukwuemeka E Nwachukwu prepared the 'Summary of findings’ table and the first draft of the review. All authors read, gave input to all sections and approved the final version.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

Nigerian branch of the South African Cochrane Center, Calabar, Nigeria.

Technical support during the review process

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None known.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Bartha 2005 {published data only}

- Bartha JL, Romero‐Carmona R, Martinez‐Del‐Fresno P, Comino‐Delgado R. Bishop score and transvaginal ultrasound for preinduction cervical assessment: a randomised clinical trial. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2005;25:155‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Park 2011 {published data only}

- Park KH, Kim SN, Lee SY, Jeong EH, Jung HJ, Oh KJ. Comparison between sonographic cervical length and Bishop score in preinduction cervical assessment: a randomized trial. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2011;38(2):198‐204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Ryu 2013 {published data only}

- Ryu A, Park KH, Lee SY, Jeong EH, Oh KJ, Kim A. Ultrasonographic cervical length versus Bishop score for preinduction cervical assessment in parous women: a randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2013;208(Suppl 1):S134. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Ahner 1995

- Ahner R, Egarter C, Kiss H, Heinzl K, Zeillinger R, Schatten C, et al. Fetal fibronectin as a selection criterion for induction of term labor. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1995;173:1513‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baacke 2006

- Baacke KA, Edwards RK. Preinduction cervical assessment. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2006;49(3):563‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bishop 1964

- Bishop EH. Pelvic scoring for elective induction. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1964;24:266‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blanch 1996

- Blanch G, Olah KSJ, Walkinshaw S. The presence of fetal fibronectin in cervicovaginal secretions of women at term‐Its role in the assessment of women before labor induction and in the investigation of the physiologic mechanisms of labor. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;174:262‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burnett 1966

- Burnett JE. Preinduction scoring: an objective approach to induction of labor. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1966;28:479‐83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 2012

- Cooper S, Lange I, Wood S, Tang S, Miller L, Ross S. Diagnostic accuracy of rapid phIGFBP‐I assay for predicting preterm labor in symptomatic patients. Journal of Perinatology 2012;32:460‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crane 2006

- Crane JMG. Factors predicting labor induction success: a critical analysis. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2006;49(3):573‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crane 2008

- Crane JM, Hutchens D. Transvaginal sonographic measurement of cervical length to predict preterm birth in asymptomatic women at increased risk: a systematic review. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2008;31(5):579‐87. [PUBMED: 18412093] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Edwards 2000

- Edwards RK, Richards DS. Preinduction cervical assessment. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;43(3):440‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eggebo 2009

- Eggebo TM, Okland I, Heien C, Gjessing LK, Romundstad P, Salvesen SA. Can ultrasound measurements replace digitally assessed elements of the Bishop score?. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica 2009;88:325‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ekman 1995

- Ekman G, Granstrom L, Malmstrom A, Sennstrom M, Svensson J. Cervical fetal fibronectin correlates to cervical ripening. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1995;74:698‐701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Elizur 2005

- Elizur SE, Yinon Y, Epstein GS, Seidman DS, Schiff E, Sivan E. Insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐1 detection in preterm labor: evaluation of a bedside test. American Journal of Perinatology 2005;22(6):305‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ezebialu 2013

- Ezebialu IU, Eke AC, Eleje GU, Nwachukwu CE. Methods for assessing pre‐induction cervical ripening. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010762] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Garite 1996

- Garite TJ, Casal D, Garcia‐Alonso A, Kreaden U, Jimenez G, Ayala JA, et al. Fetal fibronectin: a new tool for the prediction of successful induction of labor. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;175:1516‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goldberg 1997

- Goldberg J, Newman RB, Rust PF. Interobserver reliability of digital and endovaginal ultrasonographic measurements. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1997;177:853‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Harrison 1977

- Harrison RF, Flynn M, Craft I. Assessment of factors constituting an ‘‘inducibility profile’’. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1977;49:270‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hatfield 2007

- Hatfield AS, Sanchez‐Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Sonographic cervical assessment to predict the success of labor induction: a systematic review with metaanalysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2007;197(2):186‐92. [PUBMED: 17689645] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hendrix 1998

- Hendrix NW, Chauhan SP, Morrison JC, Magnan EF, Martin JN Jr, Devoe LD. Bishop score: a poor diagnostic test to predict failed induction versus vaginal delivery. Southern Medical Journal 1998;91:248‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hou 2012

- Hou L, Zhu Y, Ma X, LiB J, Zhang W. Clinical parameters for prediction of successful labor induction after application of intravaginal dinoprostone in nulliparous Chinese women. Medical Science Monitor 2012;18(8):CR518‐522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Keepanasseril 2007

- Keepanasseril A, Suri V, Bagga R, Aggarwal N. Pre‐induction sonographic assessment of the cervix in the prediction of successful induction of labour in nulliparous women. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2007;47:389‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Keepanasseril 2012

- Keepanasseril A, Suri E, Bagga R, Aggarwal N. A new objective scoring system for the prediction of successful induction of labour. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2012;32:145‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lawani 2014

- Lawani OL, Onyebuchi AK, Iyoke CA, Okafo CN, Ajah LO. Obstetric outcome and significance of labour induction in a health resource poor setting. Obstetrics and Gynecology International 2014;2014:419621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leppert 1995

- Leppert PC. Anatomy and physiology of cervical ripening. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 1995;38(2):267‐79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Martina 1997

- Martina NA, Kim E, Chitkara U, Wathen NC, Chard T, Giudice LC. Gestational age dependent expression of Insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐1 (IGFBP‐1) phosphoforms in human extraembryonic cavity, materna serum and decidua suggests decidua as the primary source of IGFBP‐1 in these fluids during early pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1997;82:1894‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meijer‐Hoogeveen 2009

- Meijer‐Hoogeveen M, Roos C, Arabin B, Stoutenbeek P, Visser GH. Transvaginal ultrasound measurement of cervical length in the supine and upright positions versus Bishop score in predicting successful induction of labor at term. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2009;33(2):213‐20. [PUBMED: 19173229] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mouw 1998

- Mouw RJC, Egberts J, Kragt H, Roosemalen JV. Cervicovaginal fetal fibronectin concentrations: predictive value of impending birth in postterm pregnancies. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 1998;80:67‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nuutila 1999

- Nuutila M, Hiilesmaa V, Karkkainen T, Ylikorkala O, Rutanen E. Phosphorylated isoforms of insulin‐like growth factor binding protein‐1 in the cervix as a predictor of cervical ripeness. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1999;94(2):243‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ojutiku 2002

- Ojutiku D, Jones G, Bewley S. Quantitative foetal fibronectin as a predictor of successful induction of labour in post‐date pregnancies. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 2002;101:143‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pandis 2001

- Pandis GK, Papageorghiou AT, Ramanathan VG, Thompson MO, Nicolaides KH. Preinduction sonographic measurement of cervical length in the prediction of successful induction labor. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;18:623‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Park 2007

- Park KH. Transvaginal ultrasonographic cervical measurement in predicting failed labor induction and cesarean delivery for failure to progress in nulliparous women. Journal of Korean Medical Science 2007;22(4):722‐7. [PUBMED: 17728517] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rane 2003

- Rane SM, Pandis GK, Guirgis RR, Higgins B, Nicolaides KH. Pre‐induction sonographic measurement of cervical length in prolonged pregnancy: the effect of parity in the prediction of induction‐to‐delivery interval. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2003;22(1):40‐4. [PUBMED: 12858301] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rane 2004