Abstract

Background

Extensive evidence shows that well over 50% of people prefer to be cared for and to die at home provided circumstances allow choice. Despite best efforts and policies, one‐third or less of all deaths take place at home in many countries of the world.

Objectives

1. To quantify the effect of home palliative care services for adult patients with advanced illness and their family caregivers on patients' odds of dying at home; 2. to examine the clinical effectiveness of home palliative care services on other outcomes for patients and their caregivers such as symptom control, quality of life, caregiver distress and satisfaction with care; 3. to compare the resource use and costs associated with these services; 4. to critically appraise and summarise the current evidence on cost‐effectiveness.

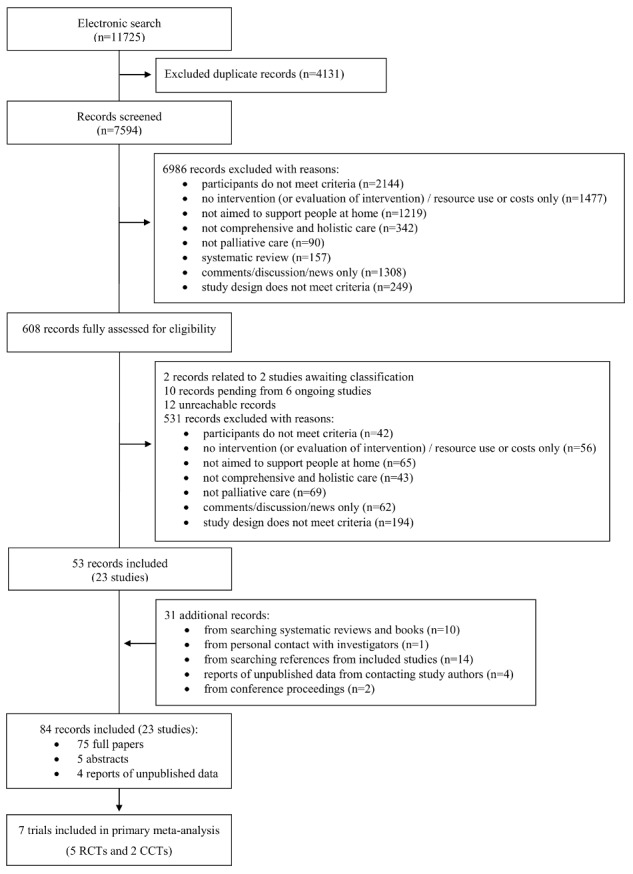

Search methods

We searched 12 electronic databases up to November 2012. We checked the reference lists of all included studies, 49 relevant systematic reviews, four key textbooks and recent conference abstracts. We contacted 17 experts and researchers for unpublished data.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials (CCTs), controlled before and after studies (CBAs) and interrupted time series (ITSs) evaluating the impact of home palliative care services on outcomes for adults with advanced illness or their family caregivers, or both.

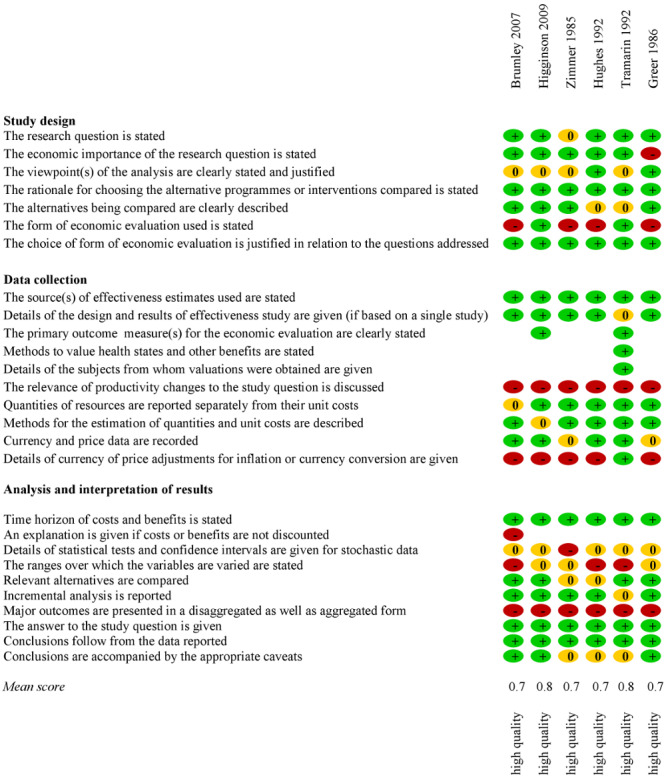

Data collection and analysis

One review author assessed the identified titles and abstracts. Two independent reviewers performed assessment of all potentially relevant studies, data extraction and assessment of methodological quality. We carried out meta‐analysis where appropriate and calculated numbers needed to treat to benefit (NNTBs) for the primary outcome (death at home).

Main results

We identified 23 studies (16 RCTs, 6 of high quality), including 37,561 participants and 4042 family caregivers, largely with advanced cancer but also congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), HIV/AIDS and multiple sclerosis (MS), among other conditions. Meta‐analysis showed increased odds of dying at home (odds ratio (OR) 2.21, 95% CI 1.31 to 3.71; Z = 2.98, P value = 0.003; Chi2 = 20.57, degrees of freedom (df) = 6, P value = 0.002; I2 = 71%; NNTB 5, 95% CI 3 to 14 (seven trials with 1222 participants, three of high quality)). In addition, narrative synthesis showed evidence of small but statistically significant beneficial effects of home palliative care services compared to usual care on reducing symptom burden for patients (three trials, two of high quality, and one CBA with 2107 participants) and of no effect on caregiver grief (three RCTs, two of high quality, and one CBA with 2113 caregivers). Evidence on cost‐effectiveness (six studies) is inconclusive.

Authors' conclusions

The results provide clear and reliable evidence that home palliative care increases the chance of dying at home and reduces symptom burden in particular for patients with cancer, without impacting on caregiver grief. This justifies providing home palliative care for patients who wish to die at home. More work is needed to study cost‐effectiveness especially for people with non‐malignant conditions, assessing place of death and appropriate outcomes that are sensitive to change and valid in these populations, and to compare different models of home palliative care, in powered studies.

Keywords: Adult, Female, Humans, Male, Attitude to Death, Caregivers, Cost-Benefit Analysis, Critical Illness, Critical Illness/nursing, Home Care Services, Home Care Services/economics, Palliative Care, Palliative Care/economics, Palliative Care/methods, Patient Preference, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Treatment Outcome

Plain language summary

Effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of home‐based palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers

When faced with the prospect of dying with an advanced illness, the majority of people prefer to die at home, yet in many countries around the world they are most likely to die in hospital. We reviewed all known studies that evaluated home palliative care services, i.e. experienced home care teams of health professionals specialised in the control of a wide range of problems associated with advanced illness – physical, psychological, social, spiritual. We wanted to see how much of a difference these services make to people's chances of dying at home, but also to other important aspects for patients towards the end of life, such as symptoms (e.g. pain) and family distress. We also compared the impact on the costs with care. On the basis of 23 studies including 37,561 patients and 4042 family caregivers, we found that when someone with an advanced illness gets home palliative care, their chances of dying at home more than double. Home palliative care services also help reduce the symptom burden people may experience as a result of advanced illness, without increasing grief for family caregivers after the patient dies. In these circumstances, patients who wish to die at home should be offered home palliative care. There is still scope to improve home palliative care services and increase the benefits for patients and families without raising costs.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings.

| Outcomes: home palliative care vs. usual care | |||||

|

Patient or population: adult patients with a severe or advanced disease (malignant or non‐malignant) Settings: Canada, Italy, Norway, Sweden, UK, US Intervention: home palliative care Comparison: usual care, which could include community care (primary or specialist care at home and in nursing homes), hospital care (inpatient and outpatient) and in some instances palliative or hospice care (or both) | |||||

| Outcomes | Number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB)a (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) |

Level of evidenceb (adapted fromVan Tulder 2003) |

Comments |

|

Home death follow‐up: 3 to 24 months Analysis 1.1 and Analysis 1.2 |

With study population control risk (307 home deaths/1000 deaths) NNTB 5 (3 to 14), meaning that for one additional patient to die at home five more would need to receive home palliative care as opposed to usual care With low home death population assumed control risk (ACR) (128 home deaths/1000 deaths) NNTB 9 (5 to 26) With medium home death population ACR (278 home deaths/1000 deaths) NNTB 6 (3 to 15) With high home death population ACR (454 home deaths/1000 deaths) NNTB 5 (3 to 13) |

OR 2.21 (1.31 to 3.71) |

1222 (7 studies, 3 of high quality; 5 RCTs and 2 CCTs) |

Strong | The majority of patients had cancer but 3 trials also included non‐cancer conditions. 3 interventions provided specialist palliative care and 4 provided intermediate palliative care The direction of the effect was consistent across all studies but did not reach statistical significance in 3; ORs ranged from 1.36 (95% CI 0.80 to 2.31) to 2.86 (95% CI 0.78 to 10.53) Sensitivity analyses showed that exclusion of the 2 CCTs (both of Swedish hospital‐based services with a pooled OR 3.44, 95% CI 0.60 to 19.57) and inclusion of only high quality RCTs resulted in a reduction of the OR to 1.28 (95% CI 1.28 to 2.33) and 1.75 (95% CI 1.24 to 2.47) respectively, with more precision and less heterogeneity |

|

Symptom burden follow‐up: 1 month from enrolment to the week of death Table 2 |

Not calculated, data were not pooled due to the high degree of heterogeneity. See comments | 2107 (4 studies, 2 of high quality; 3 RCTs and 1 CBA) |

Strong | Strong evidence of a positive effect on symptom burden: statistically significant reduction of symptom burden in 3 studies (one UK RCT of high quality) further to marginally significant positive effect among 209 patients in Bakitas 2009 (US RCT of high quality; P value = 0.06) Effect sizes were small (ranging from difference in mean scores of 0.08 in a 0 to 7 scale to a difference of 2.1 in a 0 to 20 scale). All studies used different measures 1 study evaluated a specialist palliative care intervention for patients with MS. The other 3 included only patients with cancer (1 evaluated a specialist service and 2 evaluated intermediate palliative care) |

|

|

Pain follow‐up: 1 week from enrolment to week of death Table 3 |

Not calculated, data were not pooled due to the high degree of heterogeneity. See comments | 2735 (9 studies; 4 high quality; 8 RCTs and 1 CBA) |

Conflicting | 2 UK RCTs (one of high quality) and Greer 1986 found statistically significant positive effects (the latter favouring the hospital‐based intervention); a marginally significant positive effect was found among 83 patients in McKegney 1981 in the last month before death (high quality RCT; P value = 0.06). The remaining 6 trials (including 1 high quality RCT) found no statistically significant group differences High variability in outcome measures (only the McGill‐Melzack Pain Questionnaire was used more than once) |

|

|

Physical function follow‐up: 1 month from enrolment to week of death Table 4 |

Not calculated, data were not pooled due to the high degree of heterogeneity. See comments | 2408 (7 studies, 3 high quality; 6 RCTs and 1 CBA) |

Inconclusive | Statistical significance unknown in 2 out of 7 studies hence the evidence was deemed inconclusive 3 RCTs in the UK, Norway and the US (all of high quality) found no statistically significant group differences, while two RCTs of intermediate palliative care services in the US (McCorkle 1989; Aiken 2006) detected significantly better physical functioning trajectories in the intervention group through longitudinal analysis up to 9 months following enrolment |

|

|

Quality of life follow‐up: 1 month from enrolment to week of death Table 5 |

Not calculated, data were not pooled due to the high degree of heterogeneity. See comments | 2487 (7 studies; 3 of high quality; 6 RCTs and 1 CBA) |

Inconclusive | Statistical significance unknown in 2 out of 7 studies hence the evidence was deemed inconclusive. 3 RCTs (2 of high quality) found no statistically significant group differences 2 US RCTs, 1 of a specialist service (high quality; Bakitas 2009) and 1 of an intermediate service (Aiken 2006) detected significantly better quality of life through longitudinal analysis up to the month of death Effects were statistically significant both forwards from enrolment and backwards from death in analyses by Bakitas 2009; they were statistically significant in physical functioning, general health and vitality but not in pain‐related, social, emotional and mental health dimensions of quality of life in Aiken 2006 |

|

|

Caregiver burden follow‐up: 1 month from enrolment to the patients' "last weeks of life" Table 6 |

Not calculated, data were not pooled due to the high degree of heterogeneity. See comments | 1888 (3 studies; 2 of high quality; 2 RCTs and 1 CBA) |

Conflicting | Conflicting findings from 2 high quality RCTs of specialist home palliative care interventions, 1 in the US with cancer patients (Bakitas 2009 reported no group main effects or group by time interactions 1‐10 months after enrolment) and 1 in the UK with MS patients (Higginson 2009 found differences in change scores from baseline at 12 weeks' follow‐up (P value = 0.01) Greer 1986 found a small but significant difference in the last weeks of the patient's life, with higher caregiver burden in the community‐based intervention |

|

|

Caregiver grief follow‐up: from moment the patient died to 13 months after Table 7 |

Not calculated, data were not pooled due to the high degree of heterogeneity. See comments | 2113 (4 studies, 2 of high quality; 3 RCTs and 1 CBA) | Strong | Strong evidence of no effect on caregiver grief: no statistically significant differences in three RCTs in the UK and the US (two of high quality) Outcome measures varied (only the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief was used more than once but scored in different ways) Greer 1986 found significant higher emotional distress as measured by the modified Grief Experience Inventory among caregivers in the community‐based intervention assessed 90 to 120 days after the patient died |

|

|

Satisfaction with care follow‐up: 1 month from enrolment to approximately 4‐6 months after the patient died(caregiver report) Table 8 |

Not calculated, data were not pooled due to the high degree of heterogeneity. See comments | 2497 (6 studies; 4 of high quality; 5 RCTs and 1 CBA) |

Conflicting | 3 RCTs (2 of high quality) found statistically significant positive effects; the other 2 RCTs (bothhigh quality studies in the US) reported no statistically significant differences. Positive effects were related to a hospital‐based specialist service in Norway (Jordhøy 2000) and 2 intermediate services in the US (Brumley 2007; Hughes 1992) Greer 1986 found significant higher satisfaction with care among caregivers in the hospital‐based intervention assessed 90‐120 days after the patient died |

|

CBA: controlled before and after study; CCT: controlled clinical trial; CI: confidence interval; MS: multiple sclerosis; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial. aNumbers needed to treat to benefit (NNTBs) were calculated for the study population control risk and for three other assumed control risks (ACR). These were based on recent cancer home deaths rates from a population‐based study across six European countries (Cohen 2010): 1) low home death population assumed the lowest rate of 128 deaths at home per 1000 cancer deaths (Norway); 2) medium home death population assumed the mean across the six European countries (278 deaths at home per 1000 cancer deaths); 3) high home death population assumed the highest rate of 454 deaths at home per 1000 cancer deaths (the Netherlands). We applied rates related to cancer as the included studies involved largely cancer patients. bLevels of evidence: Strong: findings from meta‐analysis or consistent findings across all studies including at least two high quality RCTs Moderate: consistent findings across all studies including at least two low quality RCTs/CCTs or one high quality RCT Limited: one RCT/CCT not reaching high quality Conflicting: inconsistent findings among at least two studies with at least one RCT/CCT Inconclusive: statistical significance of differences unknown in > 25% of all studies No evidence from trials: no RCTs or CCTs Consistent (conflates assessment of direction and precision): statistically significant effect in same direction in ≥ 75% of all studies High quality RCTs/CCTs: ≥ 3.5 methodological quality score (ranging from zero to six)

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Home palliative care versus usual care, Outcome 1: Death at home

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Home palliative care versus usual care, Outcome 2: death at home with only high quality RCTs

1. Symptom burden: home palliative care versus usual care.

| Study and country | Measure |

Analysis |

Follow‐up | Significance and direction | Details |

|

Bakitas 2009 US (high quality) |

Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) measure of 9 symptoms (rated from 0 to 9): pain, activity, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite, sense of well‐being, shortness of breath; scores: from 0 to 900, higher scores equal greater symptom intensity; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 1 month | Marginally significant difference favours interventiona Mean treatment effect (intervention‐control) −27.8 (SE 5); P value = 0.06 |

Intervention (n = 109): LSM 241.81 (95% CI 216.35 to 267.28) Control (n = 100): LSM 288.53 (95% CI 262.03 to 315.03) |

| 4 months | Intervention (n = 73): LSM 254.67 (95% CI 224.55 to 284.78) Control (n = 76): LSM 271.87 (95% CI 242.11 to 301.64) |

||||

| 7 months | Intervention (n = 62): LSM 238.77 (95% CI 206.60 to 270.95) Control (n = 54): LSM 268.59 (95% CI 234.34 to 302.83) |

||||

| 10 months | Intervention (n = 48): LSM 271.57 (95% CI 235.83 to 307.31) Control (n = 45): LSM 294.20 (95% CI 257.27 to 331.12) |

||||

| 13 months | Intervention (n = 28): LSM 295.56 (95% CI 250.65 to 340.47) Control (n = 31): LSM 251.66 (95% CI 208.51 to 294.82) |

||||

| Backwards from death | Third last assessment | n.s.a Mean treatment effect (intervention‐control) −24.2 (SE 20.5) P value = 0.24 |

Intervention (n = 52): LSM 262.76 (95% CI 222.61 to 302.91) Control (n = 48): LSM 263.90 (95% CI 222.13 to 305.68) |

||

| Second last assessment | Intervention (n = 81): LSM 274.69 (95% CI 240.63 to 308.76) Control (n = 75): LSM 304.93 (95% CI 269.53 to 340.33) |

||||

| Last assessment | Intervention (n = 80): LSM 322.29 (95% CI 288.08 to 356.51) Control (n = 74): LSM 353.90 (95% CI 318.33 to 389.47) |

||||

|

Higginson 2009 UK (high quality) |

Palliative care Outcome Scale MS Symptoms subscale(POS‐MS‐S5) measure of 5 symptoms (rated from 0 to 4): pain, nausea, vomiting, mouth problems and sleeping difficulty; scores: from 0 to 20, higher scores equal greater symptom intensity; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 6 weeks | n.s.b ES ‐0.5 F = 1.08 P value = 0.31 |

M change from baseline Intervention (n = 24): M ‐0.7 (SD 2.3; 95% CI ‐1.7 to 0.3) Control (n = 20): M 0.6 (SD 3.2; 95% CI ‐1.0 to 2.1) |

| 12 weeks | Favours interventionb ES ‐0.8 F = 4.75 P value = 0.04 |

M change from baseline Intervention (n = 25): M ‐1.0 (SD 2.7; 95% CI ‐2.1 to 0.1) Control (n = 21): M 1.1 (SD 2.8; 95% CI ‐0.2 to 2.4) |

|||

|

McCorkle 1989 US |

Symptom Distress Scale measure of 13 symptoms (not stated which); scores: from 13 to 65, higher scores equal greater symptom distress; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment |

6 weeks | Favours interventionc F = 5.01 P value = 0.03 Graphs showed that the entire sample experienced increased symptom distress over time but control2 (i.e. those receiving usual outpatient care) experienced elevated distress 1 occasion sooner (at 6 weeks) than the intervention and control1 (i.e. those receiving cancer home care) |

Adjusted estimates Intervention: M 26.1 Control1 (cancer home care): M 24.88 Control2, (usual outpatient care): M 24.32 |

| 12 weeks | Adjusted estimates Intervention: M 24.23 Control1 (cancer home care): M 24.71 Control2 (usual outpatient care): M 26.79 |

||||

| 18 weeks | Adjusted estimates Intervention: M 25.42 Control1 (cancer home care): M 26.14 Control2 (usual outpatient care): M 26.70 |

||||

| Greer 1986 (CBA) |

Composite symptom severity scale modified from Melzack‐McGill Questionnaire measure of symptoms including nausea or vomiting, constipation, dizziness, fever or chills, dry mouth, breathlessness; scores: from 0 to 7, higher scores equal greater symptom severity; caregiver report |

Backwards from death |

3 weeks | Favours hospital‐based interventiond "patients in HB hospices were likely to experience fewer symptoms than HC or CC patients, although at one week prior to death this difference was statistically significant only in the HB‐CC comparison. Subgroup analyses revealed that statistically significant differences persisted regardless of the level of symptoms at intake" (Greer 1986) |

Adjusted estimatesd Community‐based intervention: M 2.89 (SE 0.09) Hospital‐based intervention: M 2.46 (SE 0.13) Control (conventional care): M 2.97 (SE 0.16) |

| 1 week | Favours intervention regardless service basedd see comment above |

Adjusted estimatesd Community‐based intervention: M 3.05 (SE 0.08) Hospital‐based intervention: M 2.78 (SE 0.12) Control (conventional care): M 3.38 (SE 0.15) |

ANCOVA: analysis of covariance; CBA: controlled before and after study; CC: conventional care (control); CI: confidence interval; ES: estimated effect size; HB: hospital‐based (hospital‐based intervention); HC: home care (community‐based intervention); LSM: estimated least mean square; M: mean; n.s.: not significant; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error. aResults from repeated measures analysis of covariance (mixed‐effects model applied to longitudinal data using random‐subject effects to account for correlation between repeated outcome measurements on same individual). bResults from F‐tests of non‐imputed data; authors stated that imputed data gave similar results. cThe authors used repeated measures analysis and analysis of variance; analysis included 78 patients who completed the three follow‐up interviews (i.e. up to 18 weeks after enrolment); adjusted means were used due to baseline differences despite randomisation. dThe authors undertook hypothesis testing on adjusted estimates of outcomes in each of the groups derived through linear regression; estimates adjusted for sample differences; standard errors based on the linear regression equation.

2. Pain: home palliative care versus usual care.

| Study | Measure | Analysis | Follow‐up | Significance and direction | Details |

|

Higginson 2009 UK (high quality) |

Palliative care Outcome Scale (POS) pain item score: from 0 to 4, higher score equals greater pain; negative change equals reduction; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment |

6 weeks | n.s. | Mean change from baseline Intervention (n = 25): ‐0.23 (95% CI ‐0.66 to 0.20) Control (n = 23): 0.09 (95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.54) |

| 12 weeks | Favours intervention F = 5.15; P value = 0.028 |

Mean change from baseline Intervention (n = 26): ‐0.46 (95% CI ‐0.98 to 0.05) Control (n = 24): 0.30 (95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.76) Adjusted for baseline scores, the difference between scores was 0.56 (95% CI ‐ 0.75 to 1.19) |

|||

|

Jordhøy 2000 Norway (high quality) |

EORTC QLQ‐C30 2‐item pain scale transformed score: from 0 to 100, higher score equals greater pain; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment |

1 month | n.s.a P value = 0.35 |

Intervention (n = 153): M 36 Control (n = 116): M 36 |

| 2 months | Intervention (n = 108): M 38 Control (n = 93): M 37 |

||||

| 4 months | Intervention (n = 71): M 41 Control (n = 65): M 37 |

||||

| 6 months | Differences and statistical significance not stated | Intervention (n = 56): M 39 Control (n = 52): M 34 |

|||

|

McKegney 1981 US (high quality) |

Sternbach Pain Estimate score score: from 0 to 100; higher score equals greater pain; patient report |

Backwards from death | 180 to 150 days | Authors stated there were no differences but statistical significance was not stated |

"The two groups had essentially the same mean pain scores until the last 90 days before death." (McKegney 1981); this statement is corroborated by graph of mean pain scores in the 2 groups |

| 150 to 120 days | |||||

| 120 to 90 days | |||||

| 90 to 60 days | Authors stated there were differences but statistical significance was not stated | "The 'Intensive' group of patients has lower mean pain scores than the 'non‐intensive' group over the last 90 days before death. In these last 90 days, the mean pain scores in the non‐intensive group of patients continued to rise until death, whereas the mean pain scores in the intensive group of patients plateaued" (McKegney 1981). The difference in the 30 to 0 days period was marginally significant (P value = 0.06) | |||

| 60 to 30 days | |||||

| 30 to 0 days | Marginally significant difference favours intervention P value = 0.06 |

||||

|

Rabow 2004 US (high quality) |

Brief Pain Inventory measure with 6 items: worst pain, least pain and "average" pain in last 24 hours (from 0 to 10); 'right now' pain (from 0 to 10); relief (from 0 to 100); interference with activities (from 0 to 70); higher scores equal greater pain; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment |

6 months | n.s.b P values ranged from 0.94 (ANCOVA between groups for interference with activities) to 0.10 (ANCOVA between groups for least pain in last 24 hours) |

Mean adjusted for baseline differences Intervention (n = 50) vs. control (n = 40)

|

| 12 months | Mean adjusted for baseline differences Intervention (n = 50) vs. control (n = 40)

|

||||

|

Aiken 2006 US |

SF‐36 2‐item bodily pain subscale transformed score: from 0 to 100; lower score equal greater pain; negative slope equals reduction; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment |

3 months | n.s.c | Growth modelling analysis (separate for COPD and CHF patients) COPD slope: intervention: 2.98 vs. control: ‐0.45 CHF slope: intervention: ‐0.57 vs. control: ‐0.45 |

| 6 months | |||||

| 9 months | |||||

|

Grande 1999 UK |

Cartwright/Addington Hall surveys pain item 4‐point item, score range not stated; higher score equal greater pain; caregiver report 6 weeks after death |

Backwards from death |

Last 2 weeks | Favours intervention P value < 0.05 |

Intervention (n = 107): M 2.52 (SD 0.93) Control (n = 21): M 3.00 (SD 1.10) Although analysis used Mann–Whitney U‐tests, authors reported Ms and SDs for clarity |

|

McCorkle 1989 US |

McGill‐Melzack Pain Questionnaire score: range not stated; higher score equal greater pain; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment |

6 weeks | n.s. |

"The three groups did not differ significantly with respect to McGill‐Melzack Pain Questionnaire" (McCorkle 1989); no data provided to support this statement |

| 12 weeks | |||||

| 6 months | |||||

|

McWhinney 1994 Canada |

McGill‐Melzack Pain Questionnaire score: range not stated; higher score equals greater pain; patient/caregiver report through diary |

Forwards from enrolment |

1 month | n.s. | "There were no clinically or statistically significant differences between the experimental and control groups on any of the measures at one month" (McWhinney 1994); no data provided to support this statement High attrition (53 /146) mainly due to death; 2 months data not analysed due to further attrition |

|

Greer 1986 (CBA) |

McGill‐Melzack Pain Questionnaire score range not stated; higher score equals greater pain; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment |

1 week | n.s.d | "the average level of pain for all three patient groups was between mild and discomforting with no statistically significant differences among the groups" (Morris 1986, Greer 1986); no data provided to support this statement |

| 5 weeks | |||||

| 1) Composite pain index modified from Spitzer Quality of Life Index score: from 0 to 4; higher score equals greater pain; caregiver report 2) Item on being pain‐free score: yes/no; caregiver report 3) Item on persistent pain score: yes/no; caregiver report |

Backwards from death |

3 weeks |

Composite pain index n.s.d Pain‐free n.s.d Persistent pain favours hospital‐based interventiond P value < 0.01 |

Adjusted estimatesd Composite pain index Community‐based intervention: M 1.41 (SE 0.08) Hospital‐based intervention: M 1.10 (SE 0.10) Control (conventional care): M 1.53 (SE 0.16) Patients pain‐free Community‐based intervention: 7% (SE 0.02) Hospital‐based intervention: 12% (SE 0.02) Control (conventional care): 9% (SE 0.04) Patients with persistent pain Community‐based intervention: 7% (SE 0.02) Hospital‐based intervention: 3% (SE 0.02) Control (conventional care): 14% (SE 0.04) |

|

| 1 week |

Composite pain index n.s.d Pain‐free n.s.d Persistent pain favours hospital‐based interventiond P value < 0.001 |

Adjusted estimatesd Composite pain index Community‐based intervention: M 1.61 (SE 0.06) Hospital‐based intervention: M 1.48 (SE 0.07) Control (conventional care): M 1.65 (SE 0.12) Patients pain‐free Community‐based intervention: 9% (SE 0.01) Hospital‐based intervention: 10% (SE 0.02) Control (conventional care): 16% (SE 0.04) Patients with persistent pain Community‐based intervention: 13% (SE 0.02) Hospital‐based intervention: 5% (SE 0.02) Control (conventional care): 22% (SE 0.05) Patient self reports failed to confirm these findings, but at 1 week to death 80% patients could not report |

ANCOVA: analysis of covariance; CBA: controlled before and after study; CHF: congestive heart failure; CI: confidence interval; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; M: mean; n.s.: not significant; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error.

aThe authors calculated mean changes from baseline at one to four months after enrolment by dividing the area under the curve scores by time; differences between groups were tested by bootstrap estimation to fit regression models allowing for clustering and predictive factors. bANCOVAs tested for differences between groups and for group by time interaction, controlling for baseline differences in pain but not for clustering. cThe authors used growth modelling analysis, calculated slopes of "average" linear trajectory within a group, averaged across slopes of individual linear trajectories of individual within the group and compared intercepts at each time point and slopes for COPD and CHF patients separately. dThe authors undertook hypothesis testing on adjusted estimates of outcomes in each of the groups derived through linear regression; estimates adjusted for sample differences; standard errors based on the linear regression equation for continuous variables and on logistic regression equation for dichotomous variables.

3. Physical function: home palliative care versus usual care.

| Study | Measure | Analysis | Follow‐up | Significance and direction | Details |

|

Higginson 2009 UK (high quality) |

MS Impact Scale (MSIS) Physical subscale score: range not stated; higher scores equal greater physical impact; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 6 weeks |

n.s.a ES 0.2 F = 0.15 P value = 0.70 |

M change from baseline Intervention (n = 16): M 1.3 (SD 17.0; 95% CI ‐7.7 to 10.4) Control (n = 7): M ‐1.7 (SD 17.5; 95% CI ‐17.9 to 10.4) |

| 12 weeks | n.s.a ES 0.4 F = 0.37 P value = 0.55 |

M change from baseline Intervention (n = 16): M ‐0.3 (SD 17.5; 95% CI ‐9.7 to 9.0) Control (n = 7): M ‐7.1 (SD 21.3; 95% CI ‐26.8 to 12.5) |

|||

|

Jordhøy 2000 Norway (high quality) |

EORTC‐QLQ‐C30 Physical functioning scale (5 items) transformed score: from 0 to 100; higher scores equal better functioning; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 1 month |

n.s.b SAUC intervention ‐8.9 vs. SAUC control ‐6.4 P value = 0.42 |

Intervention: M 47 Control: M 49 |

| 2 months |

Intervention: M 51 Control: M 52 |

||||

| 4 months |

Intervention: M 49 Control: M 54 |

||||

| 6 months | Differences and statistically significance not stated | Intervention: M 53 Control: M 56 |

|||

|

McKegney 1981 US (high quality) |

Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score: from 0 to 100; higher scores equal better performance status; patient report |

Backwards from death |

180 to 150 days | Authors stated there were no differences but statistical significance was not stated |

"It should be briefly noted that the intensive and non‐intensive patients did not differ in (...) overall health status as defined by the KPS" (McKegney 1981); no data provided to support this statement |

| 150 to 120 days | |||||

| 120 to 90 days | |||||

| 90 to 60 days | |||||

| 60 to 30 days | |||||

| 30 to 0 days | |||||

|

Aiken 2006 US |

SF‐36 2 subscales: physical functioning and role‐physical transformed score: from 0 to 100; lower scores equal lower physical functioning; negative slope equal reduction; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 3 months |

Physical functioning Favours intervention slope: z 2.50; P value < 0.05 Intercept at 9 months: z 2.16; P value < 0.05; g 0.41 Role‐physical n.s. |

Growth modelling analysis (separate for COPD and CHF patients) Physical functioning COPD slope: intervention: 1.00 vs. control: ‐0.95 CHF slope: intervention: 0.18 vs. control: ‐1.39 Control slope declined while intervention slope rose Role‐physical COPD slope: intervention: 0.57 vs. control: ‐0.14 CHF slope: intervention: ‐0.51 vs. control: 1.60 |

| 6 months | |||||

| 9 months | |||||

|

Hughes 1992 US |

Barthels Self Care Index score: range not stated; higher scores equal greater dependency; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 1 month |

n.s. Beta ‐0.58 t ‐0.11 P value = 0.92 |

ANCOVA (age, education, race, marital status, retirement due to health, prior private sector hospital use, living arrangement, and baseline care satisfaction scores – none of these factors were predictive of outcomes); descriptive data not provided |

| 6 months | n.s. t < 1 |

Intervention (n = 18): M 72.00 Control (n = 16): M 69.31 Data were analysed using t‐tests because the sample did not support regression models |

|||

|

McCorkle 1989 US |

Enforced Social Dependency Scale (10 items) score: from 10 to 54; higher scores equal greater functional dependency on others; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment |

6 weeks | Favours interventionc F = 5.72; P value = 0.02 Graphs showed that social dependency worsens in the control2 group (i.e. those receiving usual outpatient care) 6 weeks earlier than in the 2 treatment groups |

Adjusted estimates Intervention: M 22.33 Control1 (home cancer care): M 21.68 Control2 (usual outpatient care): M 21.74 |

| 12 weeks | Adjusted estimates Intervention: M 22.67 Control1 (home cancer care): M 20.97 Control2 (usual outpatient care): M 24.85 |

||||

| 18 weeks | Adjusted estimates Intervention: M 24.57 Control1 (home cancer care): M 24.90 Control2 (usual outpatient care): M 25.17 |

||||

|

Greer 1986 (CBA) |

Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) score: from 0 to 100; higher scores equal better performance status; caregiver report |

Backwards from death | 3 weeks | Authors stated there were no differences but statistical significance was not stated "the three samples exhibited similar decreases in functional performance as measured by the Karnofsky Performance Status" (Greer 1986) |

Adjusted estimates Community‐based intervention: M 29.52 (SE 0.64) Hospital‐based intervention: M 31.05 (SE 0.79), Control (conventional care): M 28.84 (SE 1.06) |

| 1 week | Adjusted estimates Community‐based intervention: M 23.72 (SE 0.54) Hospital‐based intervention: M 25.39 (SE 0.57) Control (conventional care): M 23.83 (SE 0.84) |

ANCOVA: analysis of covariance; CHF: congestive heart failure; CI: confidence interval; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ES: estimated effect size; M: mean; n.s.: not significant; SAUC: standardised area under the curve; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error.

aResults from F‐tests of non‐imputed data; authors stated that imputed data gave similar results bThe authors calculated mean changes from baseline at one to four months after enrolment by dividing the area under the curve scores by time; differences between groups were tested by bootstrap estimation to fit regression models allowing for clustering and predictive factors. cThe authors used repeated measures analysis and analysis of variance; analysis included 78 patients who completed the three follow‐up interviews (i.e. up to 18 weeks after enrolment); adjusted means were used due to baseline differences despite randomisation.

4. Quality of life: home palliative care versus usual care.

| Study | Measure | Analysis | Follow‐up | Significance and direction | Details |

|

Rabow 2004 US (high quality) |

Multidimensional Quality of Life Scale – Cancer Version scores: single item (from 0 to 10) and total scale score from 17 items (from 0 to 100); higher scores equal better quality of life; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 6 months | n.s.a P values ranged from 0.32 (ANCOVA group by time interaction for total scale score) to 0.72 (ANCOVA group main effect for total scale score) |

Adjusted estimatesa Single item Intervention (n = 50): M 7.6 Control (n = 40): M 7.0 Total scale score Intervention (n = 50): M 69.7 Control (n = 40): M 65.4 |

| 12 months | Adjusted estimatesa Single item Intervention (n = 50): M 7.5 Control (n = 40): M 7.1 Total scale score Intervention (n = 50): M 69.3 Control (n = 40): M 67.7 |

||||

|

Jordhøy 2000 Norway (high quality) |

EORTC‐QLQ‐C30 9 scales and 6 single items transformed scores: from 0 to 100; higher scores on functioning scales equal better functioning; higher scores on symptom scales equal more symptomatology; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 1 month | n.s.b P values ranged from 0.95 for the dyspnoea item to 0.10 for the social functioning scale and the financial impact item |

Mean ratings at each assessment point for each group and SAUCs for the various scores provided in Jordhoy 2001a (Jordhøy 2000) |

| 2 months | |||||

| 4 months | |||||

| 6 months | Differences and statistical significance not stated | ||||

|

Bakitas 2009 US (high quality) |

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy for Palliative Care (FACIT‐Pal) score: from 0 to 184, higher scores equal better quality of life; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 1 month | Favours interventionc M treatment effect (intervention‐control) 4.6 (SE 2); P value = 0.02 |

Intervention (n = 108): LSM 137.25 (95% CI 133.91 to 140.59) Control (n = 97): LSM 135.34 (95% CI 131.83 to 138.86) |

| 4 months | Intervention (n = 69):LSM 137.50 (95% CI 133.50 to 141.49) Control (n = 74): LSM 133.40 (95% CI 129.43 to 137.36) |

||||

| 7 months | Intervention (n = 59): LSM 141.27 (95% CI 136.98 to 145.55) Control (n = 54): LSM 131.14 (95% CI 126.63 to 135.66) |

||||

| 10 months | Intervention (n = 48): LSM 136.33 (95% CI 131.66 to 141.00) Control (n = 44): LSM 128.78 (95% CI 123.85 to 133.70) |

||||

| 13 months | Intervention (n = 27):LSM 138.12 (95% CI 132.20 to 144.03) Control (n = 31): LSM 133.44 (95% CI 127.68 to 139.20) |

||||

| Backwards from death | Third last assessment | Favours interventionc M treatment effect (intervention‐control) 8.6 (SE 3.6); P value = 0.02 |

Intervention (n = 51): LSM 139.48 (95% CI 133.34 to 145.61) Control (n = 47): LSM 130.58 (95% CI 124.20 to 136.97) |

||

| Second last assessment | Intervention (n = 79):LSM 134.19 (95% CI 128.70 to 139.67) Control (n = 75): LSM 127.79 (95% CI 122.13 to 133.46) |

||||

| Last assessment | Intervention (n = 78): LSM 130.13 (95% CI 124.63 to 135.63) Control (n = 72): LSM 119.74 (95% CI 113.74 to 125.18) |

||||

|

McWhinney 1994 Canada |

Functional Living Index – Cancer score: range and interpretation not stated; patient/caregiver report |

Forwards from enrolment | 1 month | n.s. | "There were no clinically or statistically significant differences between the experimental and control groups on any of the measures at one month" (McWhinney 1994); no data provided to support this statement High attrition (53/146) mainly due to death; 2 month data not analysed due to further attrition |

|

Aiken 2006 US |

SF‐36 8 subscales transformed score from 0 to 100; higher scores equal better functioning; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 3 months |

Physical functioning favours intervention (slope: z 2.50, P value < 0.05; intercept at 9 months: z 2.16, P value < 0.05, g 0.41) General health favours intervention (slope: z 2.16, P value < 0.05; intercept at 9 months: z 2.51, P value < 0.05, g 0.47) Vitality favours intervention (intercept at 3 months for COPD only: z 2.36, P value < 0.05, g 0.76) Social functioning, role‐physical, bodily pain, role‐emotional, mental health subscales n.s. |

Growth modelling analysis (separate for COPD and CHF patients) Slopes of "average" linear trajectory within COPD and CHF groups ("averaged across slopes of individual linear trajectories of individual within the group") provided in Aiken 2006 Physical functioning: intervention patients in both diagnoses remained the same over time (CHF) or improved (COPD) over time, while control patients declined over time. At the 9‐month point, intervention patients' physical functioning exceeded that of controls General health: the "average" slope for intervention patients was higher than for controls and the intervention intercept exceeded that of controls at 9 months Vitality: there was an intercept difference for COPD at 3 months, with intervention patients having higher vitality scores than controls; no difference between conditions was observed for CHF |

| 6 months | |||||

| 9 months | |||||

|

Tramarin 1992 Italy |

Quality Well‐Being (QWB) Scale score: from 0 (death) to 1.0 (asymptomatic optimal functioning); higher scores equal better health; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment |

Weekly time points (authors plotted data from 6 to 12 months after enrolment) | Authors stated there were differences but statistical significance was not stated |

"Although QWB scores declined progressively in both groups, an increment in well‐being was detectable in the HC group shortly after the beginning of care" (Tramarin 1992); graph showed the increase in the intervention group occurred shortly before month 7 to month 8 (followed by a plateau at around a mean score of 0.54), while controls decreased from same initial level to mean score of around 0.44 at month 8) |

|

Greer 1986 (CBA) |

1) HRCA Quality of Life Index modified from Spitzer's Quality of Life Index Score: from 0 to 10; higher scores equal better quality of life; patient report 2) Uniscale A Unidimensional Q‐L score: from 0 to 14; higher scores equal better quality of life; patient report |

Backwards from death | 3 weeks | Authors stated there were no differences but statistical significance was not stated "Other measures, such as the HRCA Quality of Life Index (...) were comparable in the three systems of care"; "the three samples exhibited similar decreases in functional performance as measured by the (...) Uniscale" (Greer 1986) |

Adjusted estimatesd HRCA Community‐based intervention: M 3.90 (SE 0.13) Hospital‐based intervention: M 4.15 (SE 0.16) Control (conventional care): M 3.64 (SE 0.27) Uniscale Community‐based intervention: M 3.31 (SE 0.09) Hospital‐based intervention: M 3.51 (SE 0.12) Control (conventional care): M 3.60 (SE 0.19) |

| 1 week | Adjusted estimatesd HRCA Community‐based intervention: M 2.99 (SE 0.08) Hospital‐based intervention: M 3.04 (SE 0.10) Control (conventional care): M 3.24 (SE 0.16) Uniscale Community‐based intervention: M 2.92 (SE 0.07) Hospital‐based intervention: M 3.10 (SE 0.07) Control (conventional care): M 3.09 (SE 0.11) |

ANCOVA: analysis of covariance; CHF: congestive health failure; CI: confidence interval; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EORTC‐QLQ‐C30: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life questionnaire; LSM: estimated least mean square; M: mean; n.s.: not significant; SAUC: standardised area under the curve; SE: standard error. aANCOVAs tested for differences between groups and for group by time interaction, controlling for baseline differences in pain but not for clustering; means adjusted for baseline scores. bThe authors calculated mean changes from baseline at one to four months after enrolment by dividing the area under the curve scores by time; differences between groups were tested by bootstrap estimation to fit regression models allowing for clustering and predictive factors. cResults from repeated measures analysis of covariance (mixed‐effects model applied to longitudinal data using random‐subject effects to account for correlation between repeated outcome measurements on same individual). dEstimates adjusted for sample differences; standard errors based on the linear regression equation.

5. Caregiver burden: home palliative care versus usual care.

| Study | Measure | Analysis | Follow‐up | Significance and direction | Details |

|

Higginson 2009 UK (high quality) |

Zarit Burden Inventory (12 items) score: from 0 to 48, higher scores equal greater burden); caregiver report |

Forwards from enrolment | 6 weeks | n.s. |

M change from baseline Intervention (n = 24): 1.10 (95% CI ‐3.43 to 5.63) Control (n = 20): ‐1.13 (95% CI ‐3.41 to 1.14) |

| 12 weeks | Favours intervention F = 7.96 P value = 0.011 |

M change from baseline Intervention (n = 25): ‐2.88 (95% CI ‐5.99 to 0.24) Control (n = 23): 1.58 (95% CI ‐0.51 to 3.67) |

|||

|

Bakitas 2009 US (high quality) |

Montgomery Borgatta Caregiver Burden Scale (14 items, 3 subscales: objective burden, stress burden and demand burden) scores: range not stated; caregiver report |

Forwards from enrolment | 1 month | n.s.a P value > 0.05 |

"There were no significant main effects or interactions for Time, Condition, or Patient Gender for any of the measures of caregiver burden (all P values > 0.05)" (O'Hara 2010, Bakitas 2009); no data provided to support this statement |

| 4 months | |||||

| 7 months | |||||

| 10 months | |||||

| Greer 1986 (CBA) |

Study‐specific perceived caregiving burden measure score: from 0 to 6; higher scores equal greater burden; caregiver report |

Backwards from death | not clear: 'last weeks of life' |

Caregiver burden significantly higher in community‐based interventionb (not clear if against hospital‐based intervention, control or both) |

Adjusted estimatesb Community‐based intervention: M 3.32 (SE 0.07) Hospital‐based intervention: M 2.91 (SE 0.09) Control (conventional care): M 3.13 (SE 0.16) "Although one might expect the burden reported by HC PCPs to be much higher, given the greater level of instrumental care provided by HC PCPs in the last weeks of life, the differences observed were small, although statistically significant" (Greer 1986) |

CBA: controlled before and after study; CI: confidence interval; HC: home care (community‐based intervention); M: mean; n.s.: not significant; PCP; primary care person; SE: standard error. aThe authors used mixed effects modelling for repeated measures and adopted a factorial design of time, condition (intervention vs. control), and patient gender (male, female) with an unstructured covariance matrix. The contribution of each independent variable was tested as a main effect and in interaction with the other independent variables for each of the three caregiver burden subscales. bThe authors undertook hypothesis testing on adjusted estimates of outcomes in each of the groups derived through linear regression. Although statistical significance was stated in the text, no details of the test results were given; estimates adjusted for sample differences; standard errors based on the linear regression equation.

6. Caregiver grief: home palliative care versus usual care.

| Study | Measure | Analysis | Follow‐up | Significance and direction | Details | |

|

Bakitas 2009 US (high quality) |

Measure not stated score: total score (sum G1‐G15 items; from 0 to 60; higher scores equal greater grief); binary score for complicated grief (present if at least 3 items from G1 to G4 and G5 to G15 whose values were no less than 4 (often or always) separately); caregiver report |

Forwards from death | Approximately 4 to 6 months |

Grief total score n.s. t‐test P value = 0.56 Complicated grief n.s. P value = 1.0 |

Grief total score Intervention (n = 50): M 22.24 (SD 11.22) Control (n = 36): M 20.72 (SD 12.39) Complicated grief Intervention: 8/50 (16%) Control: 6/36 (17%) |

|

|

Jordhøy 2000 Norway (high quality) |

13‐item scale developed from the 21‐item Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (new scale called ‘TRIG100') transformed scores: from 0 to 100; higher scores equal high grief reactions; caregiver report |

Forwards from death | 1 month | n.s.a group by time interaction F = 0.348 P value = 0.790 (power 0.131) |

n.s. t‐test ‐0.05 P value = 0.959 |

Intervention: M 70.86 (SD 2.76) Control: M 71.11 (SD 4.41) |

| 3 months | n.s. t‐test 0.14 P value = 0.888 |

Intervention: M 71.71 (SD 2.76) Control: M 71.06 (SD 3.89) |

||||

| 6 months | n.s. t‐test ‐0.08 P value = 0.935 |

Intervention: M 67.23 (SD 3.08) Control: M 67.64 (SD 3.98) |

||||

| 13 months | n.s. t‐test 0.44 P value = 0.659 |

Intervention: M 67.20 (SD 2.95) Control: M 64.97 (SD 4.28) |

||||

|

Grande 1999 UK |

Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (TRIG): Scale 1 ‐ grief at time of death (8 items) and Scale 2 ‐ grief at time of scale completion (13 items) scores: range not stated; higher scores equal worse outcome; caregiver report |

Forwards from death | 6 months | 2 TRIG scales n.s. |

TRIG Scale 1 (at time of death) Intervention (n = 74): M 19.1 (SD 6.9) Control (n = 16): M 20.1 (SD 8.7) TRIG Scale 2 (6 months after death) Intervention (n = 70): M 46.5 (SD 12.9) Control (n = 15): M 46.8 (SD 11.8) Comparisons of scores of people who received and did not receive the intervention (27 people in intervention group did not receive the service) showed no differences |

|

|

Greer 1986 (CBA) |

Modified Grief Experience Inventory score: from 0 to 10; higher scores equal greater grief; caregiver report |

Forwards from death | 90 to 120 days | Comparison between intervention and control not stated (authors only referred to significant differences between hospital‐based vs. community‐based intervention favouring the former) "HC PCPs reported significantly greater emotional distress, as measured by a modified Grief Experience Inventory, than did HB PCPs" (Greer 1986) |

Adjusted estimatesb Community‐based intervention: M 5.06 (SE 0.11) Hospital‐based intervention: M 4.49 (SE 0.13) Control (conventional care): M 4.82 (SE 0.19) |

|

HC: home care; M: mean; n.s.: non‐significant; PCP: primary care person; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error. aLongitudinal analysis of 92 caregivers who turned the four questionnaires (months since death of patient was the within subject factor in MANOVA and group was the between subject factor). MANOVA analysis also showed that grief reactions changed significantly over time (F = 8.145; P value < 0.001; power 0.997) but the pattern of change did not differ significantly between intervention and control groups. bEstimates adjusted for sample differences; standard errors based on the linear regression equation.

7. Satisfaction with care: home palliative care versus usual care.

| Study | Measure | Analysis | Follow‐up | Significance and direction | Details |

|

Jordhøy 2000 Norway (high quality) |

FAMCARE (20 5‐point items) transformed score from 0 to 100; higher scores equal greater satisfaction; caregiver report Note: item scores are presented in inverse scale, i.e. lower scores equal greater satisfaction |

Backwards from death | 1 month after death | Favours intervention F = 7.11 P value = 0.008 Eta2 0.040 b 7.68 (SE 3.15) t 2.44 P value = 0.016 (adjusted for relationship to deceased, sex and age of caregiver, cancer, sex of patient, time since inclusion in the study, place of death) |

Intervention (n = 112): M 71.68 (SD 20.03) Control (n = 68): M 63.08 (SD 22.43) Difference (intervention minus control) of 8.60 points reduced to 7.7 controlling for others variables Item analyses using t‐test showed 10 items with P value < 0.05; 3 items P value ≥ 0.05 and < 0.10; 7 items P value ≥ 0.01 (details in Ringdal 2002, Jordhøy 2000) |

|

Rabow 2004 US (high quality) |

25 items (5‐point Likert scale) from the Group Health Association of America Consumer Satisfaction Survey score: from 20 to 100; higher scores equal greater satisfaction; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 6 months | ANCOVA group main effect: n.s. F = 1.31 P value = 0.26 ANCOVA group by time interaction: n.s. F = 0.61 P value = 0.44 |

Adjusted estimates Intervention (n = 50): M 69.6 Control (n = 40): M 74.5 |

| 12 months | Adjusted estimates Intervention (n = 50): M 70.1 Control (n = 40): M 72.4 |

||||

|

Bakitas 2009 US (high quality) |

Revised version of Teno's After Death Bereaved Family Member Interview overall rating item: range not stated; higher scores equal greater satisfaction; caregiver report |

Backwards from death | Approximately 4‐6 months after death |

Overall rating n.s. P value = 0.91 |

Overall rating Intervention (n = 50): M 41.08 (SD 12.26) Control (n = 36): M 40.78 (SD 11.61) Note: authors also measured a number of different dimensions of care satisfaction but found no statistically significant differences and only 1 marginally significant difference (P value = 0.06) in how the services responded to caregiver distress (rated better in the intervention group; M 4.5 score, SD 3.16 vs. M 3.28, SD 2.72 in the control group). Other dimensions of care examined included provision of family support, patient spiritual support, co‐ordination of care, shared decision‐making, information about symptoms and response to unmet needs and preferences, respect and individual‐focused care and quality of pre‐palliative cancer care |

|

Brumley 2007 US (high quality) |

Reid‐Gundlach Satisfaction with Services instrument (12 items) score: unknown to 48; higher scores equal greater satisfaction; dichotomised for analysis ≥ 37 very satisfied)a; patient report (or caregiver if the patient was unable to take part in telephone interview) |

Forwards from enrolment | 30 days | Favours intervention logistic regression OR 3.37 (95% CI 1.42 to 8.10); P value = 0.006 |

n = 216 Intervention: 93.1% very satisfied Control: 80.0% very satisfied |

| 60 days | n.s. logistic regression OR 1.79 (95% CI 0.65 to 4.96); P value = 0.26 |

n = 168 Intervention: 92.3% very satisfied Control: 87.0% very satisfied |

|||

| 90 days | Favours interventionb log regression OR 3.37 (95% CI 0.65 to 4.96); P value = 0.03 |

n = 149 Intervention: 93.4% very satisfied Control: 80.8% very satisfied |

|||

|

Hughes 1992 US |

Adapted US hospice study scale (17 items) score: from 1 to 3, higher scores equal greater satisfaction; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 1 month | Favours intervention Beta 0.13 t 2.15 P value = 0.04 |

ANCOVA (age, education, race, marital status, retirement due to health, prior private sector hospital use, living arrangement, and baseline care satisfaction scores – none of these factors were predictive of outcomes); descriptive data not provided |

| 6 months | Marginally significant difference favouring intervention t ‐1.98 P value = 0.06 |

Intervention (n = 17): M 2.72 Control (n = 14): M 2.45 Data were analysed using t‐tests because the sample did not support regression models |

|||

|

Adapted US hospice study scale (17 items) score: from 1 to 3, higher scores equal greater satisfaction; caregiver report |

1 month | Favours intervention Beta 0.18 t 3.46 P value = 0.0007 |

ANCOVA (caregiver age, race, education, relationship to patient, care satisfaction baseline score); descriptive data not provided | ||

| 6 months | n.s. Beta 0.12 t 1.59 P value = 0.12 |

ANCOVA (caregiver age, race, education, relationship to patient, care satisfaction baseline score); descriptive data not provided | |||

| Greer 1986 (CBA) |

Modified Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale score: from 1 to 5; higher scores equal greater satisfaction; patient report |

Forwards from enrolment | 3 weeks | n.s.c "No significant differences were observed in patient‐reported levels of satisfaction, which were uniformly high in all settings" (Greer 1986) |

Adjusted estimatesc Community‐based intervention: M 4.87 (SE 0.51) Hospital‐based intervention: M 3.76 (SE 0.98) Control (conventional care): M 4.20 (SE 0.71) |

| 1 week | Adjusted estimatesc Community‐based intervention: M 3.56 (SE 0.44) Hospital‐based intervention: M 4.60 (SE 0.72) Control (conventional care): M 5.20 (SE 0.75) |

||||

| 1) Modified Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale score: from 1 to 5; higher scores equal greater satisfaction; caregiver report pre and after death 2) Item on caregiver regret concerning the medical treatment the patient received (yes/no; caregiver report after death only) |

Pre death (time point not stated) |

Adjusted estimatesc Community‐based intervention: M 4.39 (SE 0.04), Hospital‐based intervention: M 4.54 (SE 0.05) Control (conventional care): M 4.38 (SE 0.09) |

|||

| Backwards from death | 90‐120 days after death |

Modified Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale favours hospital‐based interventionc "HB [hospital‐based] PCPs [primary care person], both before and after the patient's death, reported higher satisfaction with the patient's care than CC [conventional care] PCPs"; "small but significantly higher level of satisfaction reported by HB family members" (Greer 1986) Regret concerning patient medical treatment n.s. "Few PCPs (...) reported increased (...) regret concerning the medical treatment the patient received (11%), with no statistically significant differences among settings" (Greer 1986) |

Adjusted estimatesc Modified Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale Community‐based intervention: M 4.36 (SE 0.04) Hospital‐based intervention: M 4.48 (SE 0.05) Control (conventional care): M 4.33 (SE 0.08) Regret concerning patient medical treatment Descriptive data by group not provided |

ANCOVA: analysis of covariance; b: metric regression coefficient; CI: confidence interval; M: mean; n.s.: non‐significant; OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation; SE: standard error. aThere were no differences in the dichotomised variable at baseline but there were statistically significant differences in the continuous variable favouring the intervention over control (M 39.3 (SD 6.2) vs. 40.8 (SD 5.2); P value = 0.03). bLast point of analysis because reduction in sample size at 120 days (n = 136) resulted in the exclusion of this data in analyses. cThe authors undertook hypothesis testing on adjusted estimates of outcomes in each of the groups derived through linear regression. Although statistical significance was stated in the text, no details of the test results were given; estimates adjusted for sample differences; standard errors based on the linear regression equation for continuous variables and on logistic regression equation for dichotomous variables.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings.

| Economic data: home palliative care vs. usual care | |||

|

Patient or population: adult patients with a severe or advanced disease (malignant /or non‐malignant) Settings: Italy, UK, US Intervention: home palliative care Comparison: usual care, which could include community care (primary or specialist care at home and in nursing homes), hospital care (inpatient and outpatient) and in some instances palliative or hospice care (or both) | |||

| Economic data | No of participants (studies) |

Level of evidencea (adapted fromVan Tulder 2003) |

Comments |

|

ED visits Time horizon: 6 months following enrolment; from enrolment to death, transfer to hospice care or study end; last 2 weeks before death Table 10 |

1103 (6 RCTs; 3 high quality) |

Moderate | Moderate evidence of no statistically significant effect on ED visits: consistent across 4 RCTs. In addition, subanalysis of last 2 weeks of life for 33 patients that died in Zimmer 1985 found no ED visits in either group A significant reduction in ED use as a result of receiving home palliative care was found only in Brumley 2007 (high quality RCT conducted with patients with cancer, CHF and COPD in the US), where 20% of intervention patients had ED visits during the study period as opposed to 33% of those in usual care (P value = 0.01) |

|

Total care costs time horizon: 12 weeks or 6 months following enrolment; from enrolment to death, transfer to hospice care or study end; last 2 weeks before death Table 11 |

2047 (6 studies; all high quality economic evaluations; 5 RCTs and 1 CBA) |

Inconclusive | All studies reported lower costs in the intervention group with differences ranging from 18% to 35% (in Greer 1986 costs under the hospital‐based intervention were 2% lower than usual care as opposed to 32% lower under community‐based intervention). However, differences were statistically significant only in Brumley 2007 (the study with the largest sample size and only slightly underpowered by 3 patients as planned by authors to detect cost differences) Statistical significance not reported in 3 RCTs |

|

Cost‐effectiveness time horizon: 6 months following enrolment; from enrolment to death, transfer to hospice care or study end; last 2 weeks before death Table 11 |

2047 patients and 1678 caregivers (6 studies; all high‐quality economic evaluations; 5 RCTs and 1 CBA) |

inconclusive | Home palliative care were cost‐effective compared to usual care in Brumley 2007 (297 people with cancer, CHF and COPD) and Higginson 2009 (50 people with MS and their caregivers). However, cost‐effectiveness is unclear in the other 4 studies, as there were positive, null and negative clinical effectiveness results while costs did not differ (Hughes 1992) and the statistical significance of differences in outcomes or costs, or both, was not reported (2 trials and Greer 1986) Only Tramarin 1992 calculated a summary cost‐effectiveness measure ("average" cost‐effectiveness ratio reported in 1990 USD was USD482 per well‐week in intervention group and USD791 in control group) but with unknown statistical significance of difference or uncertainty around the estimates. In addition, Higginson 2009 plotted cost‐effectiveness planes for 2 of their outcomes. The plane for overall palliative care outcomes showed 33.8% replications in the quadrant indicating better outcomes and lower costs in the intervention group, and 54.9% in the quadrant indicating worse outcomes but lower costs. In contrast, the plane on caregiver burden showed 47.3% replications in the quadrant indicating lower costs and better outcomes and 48.0% in the quadrant showing higher costs and better outcomes |

CBA: controlled before and after study; CCT: controlled clinical trial; CHF: congestive heart failure; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED: emergency department; MS: multiple sclerosis; RCT: randomised controlled trial

aLevels of evidence: Strong: findings from meta‐analysis or consistent findings across all studies including at least two high quality RCTs Moderate: consistent findings across all studies including at least two low quality RCTs/CCTs or one high quality RCT Limited: one RCT/CCT not reaching high quality Conflicting: inconsistent findings among at least two studies with at least one RCT/CCT Inconclusive: statistical significance of differences unknown in > 25% of all studies No evidence from trials: No RCTs or CCTs Consistent (conflates assessment of direction and precision): statistically significant effect in same direction in ≥ 75% of all studies High quality RCTs/CCTs: ≥ 3.5 methodological quality score (ranging from zero to six)

8. Emergency department use.

| Study | Analysis | Time horizon | Significance and direction | Details |

|

Bakitas 2009 US (high quality) |

Forwards from enrolment |

During study period | n.s. Wilcoxon rank sum test P value = 0.53 |

Intervention: 0.86 visits Control: 0.63 visits Note: not clear if the figures are means or medians |

|

Brumley 2007 US (high quality) |

Forwards from enrolment |

During study period |

Reduced ED use in intervention group Cramer's V 0.15; P value = 0.01 linear regression adjusted for survival, age and severity of illness showed intervention reduced ED visits by 0.35 (P value = 0.02) |

Intervention: 20% had ED visits Control: 33% had ED visits |

|

Rabow 2004 US (high quality) |

Forwards from enrolment | During study period | n.s. t ‐0.24 P value = 0.81 |

Intervention (n = 50): M 1.6 visits (SD 2.2) Control (n = 40): M 1.7 visits (SD 2.8) |

|

Aiken 2006 US |

Forwards from enrolment |

During study period | n.s. overdispersed Poisson regression model predicted number of ED visits during enrolment from group, diagnosis and their interaction, controlling for total number of days in study and number of pre‐enrolment ED visits; authors stated there was no significant intervention effect. Neither was there an effect on ED visits for a subgroup of participants identified as being at high risk for ED utilisation |

Intervention: M visits/month 0.11 (SD 0.34) Control: M visits/month 0.10 (SD 0.31) Note: authors stated the number of ED visits per month remained "essentially unchanged" from 6 months prior to enrolment to period from then until the end of study |

|

Hughes 1992 US |

Forwards from enrolment |

6 months following enrolment |

VA ED visits "n.s." t 1.14 Non‐VA ED visits "n.s" t < 1 |

VA ED Intervention (n = 86): M 0.57 visits (SD 0.8) control (n = 85): M 0.72 visits (SD 0.9) non‐VA ED Intervention (n = 86): M 0.10 visits (SD 0.3) control (n = 85): M 0.08 visits (SD 0.3) |

|

Zimmer 1985 US |

Backwards from death | Last 2 weeks before death | No differences (there were no ED visits in either group) | Intervention (n = 21): 0 visits Control (n = 12): 0 visits |

ED: emergency department; M: mean; n.s.: non‐significant; SD: standard deviation; VA: Veteran Affairs.

9. Cost‐effectiveness analyses with total care costs.

| Study and sample analysed | Clinical effectiveness | Impact on resource use | Impact on total care costs | Cost‐effectiveness |

|

Brumley 2007 US N intervention = 145 N control = 152 high quality economic evaluation (mean score 0.7) |

+ death at homea + death in hospitala + patient satisfaction with care at 30 days + patient satisfaction with care at 90 days Ø patient satisfaction with care at 60 days Ø death in nursing homea Ø death in inpatient hospicea Ø survivalb |

↓ ED visits ↓ hospital admission ↓ hospital inpatient days Ø referral to hospice care |

↓ total adjusted mean costs per patientc USD7552 lower in intervention group (33% lower; 95% CI ‐ USD12,411 to ‐ USD780; P value = 0.03; R2 0.16) unadjusted difference: t 3.63; P value < 0.001 time horizon: from enrolment to death, transfer to hospice care or study end (mean survival of 196 days in intervention group and 242 days in control group; 73% patients died) currency: 2002 USD Adjusted mean costs per patientc Intervention USD2670 ± 12,523 Control USD20,222 ± 30,026 Adjusted mean costs per patient per dayc Intervention USD95.30 Control USD212.80 t ‐ 2.417; P value = 0.02 Total costs included those associated with physician visits, ED visits, hospital days, skilled nursing facility days, and home health or palliative days |

+ no summary measure, but the intervention was cost‐effective as it resulted in statistically significant improved outcomes (no negative findings), reduced resource use (no negative findings) and a statistically significant reduction in total costs |

|

Higginson 2009 UK N intervention = 26 N control = 24 high quality economic evaluation (mean score 0.8) |

+ symptom burden at 12 weeks + pain at 12 weeks + caregiver burden at 12 weeks Ø palliative care outcomes (primary outcome; at 6 and 12 weeks) Ø symptom burden 6 weeks Ø pain at 6 weeks Ø MS psychological impact at 6 and 12 weeks Ø MS physical impact at 6 and 12 weeks Ø caregiver burden 6 weeks Ø caregiver mastery (learning new skills) at 6 and 12 weeks Ø caregiver positivity at 6 and 12 weeks |

? authors reported the use of a range of health, social and voluntary services but the statistical significance of differences was not stated | Ø total mean costs per patient GBP1789 lower in intervention group (29% lower; bootstrapped 95% CI ‐ GBP5224 to GBP1902; n.s.); excluding inpatient care and informal care, mean service costs were GBP1195 lower in the intervention group (50% lower; bootstrapped 95% CI ‐ GBP2916 to GBP178; n.s.)d time horizon: 12 weeks from enrolment (only 4 deaths) currency: 2005 GBP Mean costs per patient Intervention GBP4294 Control GBP6084 Total costs included those associated with a range of health, social, and voluntary services (inpatient care, respite care, day centre, contacts with district/practice nurse, MS nurse, palliative care nurse, other nurse, general practice, specialist at home, in hospital, in a ward and in other places, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, dietician, chiropodist, dentist, speech therapist, social services) and informal care |

+ the intervention was cost‐effective as it improved caregiver burden (ZBI) with no statistically significant differences in palliative care outcomes (POS‐8) and total costs The authors plotted cost‐effectiveness planes for the two above‐mentioned outcomes (ZBI and POS‐8). These planes plot costs against outcomes forming four‐quadrants to visualise if the intervention has better outcomes and higher costs, better outcomes at lower costs, worse outcomes at higher costs or worse outcomes but at lower costs. The authors accounted for uncertainty around the cost‐effectiveness estimates by generating 1000 resamples using bootstrapping and computing cost and outcome differences for each, which were then plotted on the cost‐effectiveness planes. The point estimates in cost‐effectiveness planes suggest that the intervention was cost saving, with equivalent outcomes on overall palliative outcomes and improved outcomes for caregiver burden. The POS‐8 plane showed 33.8% replications in the lower right quadrant, indicating that intervention patients had better outcomes and lower costs than controls, and 54.9% in the quadrant indicating worse outcomes but lower costs. By contrast, in the ZBI plane, 47.3% replications were in the quadrant showing lower costs and better outcomes and 48.0% in the quadrant showing higher costs and better outcomes The authors also conducted a sensitivity analysis testing different imputation methods for dealing with missing data (last value carried, forward, next value carried backwards, and mean value), reporting similar results in nonimputed and imputed data, for all imputation methods |

|

Zimmer 1985 US N intervention = 21 N control = 12 high quality economic evaluation (mean score 0.7) |

Ø death at homea Ø survival |

? authors reported the use of a range of out‐of‐home and in‐home services but the statistical significance of differences was not stated |

? total mean costs USD716 lower in intervention group (31% lower; statistical significance and/or uncertainty not reported) time horizon: last 2 weeks before death (subanalysis of deaths within the study) currency: USD, date not stated (study conducted in 1979‐1982) Mean costs of last 2 weeks before death per patient Intervention USD1577 Control USD2293 Total costs included out‐of‐home costs (hospital days, clinic visits, nursing home days, MD office or ED visits, ambulance or chairmobile rides) and in‐home costs (MD visits, nurse visits, RN/LPN hours, aide/homemaker visits, social worker visits, laboratory technician visits, meals‐on‐wheels visits) |

? no summary measure, and it is unclear if the intervention was cost‐effective as there were no statistically significant differences in outcomes, and although total costs were lower in the intervention group, the statistical significance of this difference was not reported |

|

Hughes 1992 US N intervention = 85 N control = 86 high quality economic evaluation (mean score 0.7) |

+ patient satisfaction with care at 1 month + caregiver satisfaction with care at 1 month ‐ caregiver morale at 6 months Ø patient satisfaction with care at 6 monthse Ø caregiver satisfaction with care at 6 months Ø caregiver morale at 1 month Ø morale Ø cognitive functioning Ø physical function Ø survival |

↓ hospital inpatient daysf ↓ VA outpatient clinic visits ↓ non‐VA community nursing visits Ø ED visits (VA and non‐VA) Ø ICU days Ø nursing home days Ø hospital admission Ø non‐VA community nursing visits Ø non‐VA private home care visits Ø extended care days ? length of last hospital admission before death |

Ø total mean costs per patient USD769 lower in intervention group (18% lower; t 1.05; "n.s.") time horizon: 6 months from enrolment (mean survival was 76.2 days in intervention group and 67.1 days in control group; 79% and 78% patients died within the study, respectively) currency: 1985 USD Mean costs of 6 months following enrolment per patient Intervention USD3479.36 Control USD4248.68 Total costs included those associated with institutional care (VA and private hospitals, nursing homes) and non‐institutional (outpatient clinic visits, intervention team's visits, community nursing) |

? no summary measure, and it is unclear if the intervention was cost‐effective as there were positive and negative results in clinical outcomes and the difference in total costs was not statistically significant |

|

Tramarin 1992 Italy N intervention = 9 N control = 30 high quality economic evaluation (mean score 0.8) |

? quality of life |

? authors reported on hospital admission, length of hospital admission, hospital inpatient days and outpatient clinic visits but the statistical significance of differences was not stated | ? total '"average" costs per person‐year USD7595 lower (35% lower; statistical significance or uncertainty, or both, not reported) time horizon: costs per person‐year (6 months from enrolment multiplied by 2; 22 deaths within the study) currency: 1990 USD (converted from 1990 ITL using healthcare‐specific purchasing power parities) "Average" total costs per person‐year Intervention stage 2/3 patients USD 14, 259 stage 2 patients only USD 11,321 stage 3 patients only USD 17,237 Control stage 2/3 patients USD 21,854 stage 2 patients only USD 15,944 stage 3 patients only USD 27,764 Total costs included more than 500 items including inpatient, outpatient clinics and home care (including intervention service), hotel and general services, diagnostic examinations and therapy, treatment items, medication and personnel salaries |

? cost‐utility ratios calculated only for stage 3 patients ("average" cost‐effectiveness ratio of USD482 per well‐week in intervention group and USD791 in control group; statistical significance or uncertainty, or both, around estimates not reported) and more appropriate incremental ratios could not be calculated from the data; hence it is unclear if the intervention was cost‐effective |

|

Greer 1986 (CBA) N intervention = 1457 (833 in community‐based intervention, 624 in hospital‐based intervention) N control = 297 (conventional care) high quality economic evaluation (mean score 0.7) |

+ patient at home as long as wanted (favours community‐based intervention vs. other groups) + symptom severity at 3 weeks to death (favours hospital‐based intervention vs. other groups) + symptom severity at 1 week to death + persistent pain at 3 and 1 week to death (favours hospital‐based intervention vs. other groups) + hours of social visiting at 3 weeks to death + caregiver satisfaction with care 90 to 120 after death (favours hospital‐based intervention vs. control) + quality of death referring to 3 days before death ‐ social quality of life at 1 week to death ‐ caregiver burden in last weeks before death (higher in community‐based intervention vs. other groups) Ø patient report of pain at 1 and 5 weeks Ø survival Ø physical function at 3 and 1 week to death Ø social quality of life at 3 weeks to death Ø hours of social visiting at 1 week to death Ø hours of chatting with household members at 3 weeks to death Ø caregiver pre‐bereavement psychological well‐being (distress, use of medication for anxiety and depression, increased drinking) Ø patient satisfaction with care at 3 and 1 week to death Ø caregiver regret at 90 to 120 days after death concerning the medical care the patient received ? death at home ? caregiver satisfaction with place of death ? caregiver report of patient pain at 3 and 1 week to death (composite pain and pain‐free) ? quality of life at 3 and 1 week to death ? emotional quality of life at 3 and 1 week to death ? hours of chatting with household members at 3 weeks to death ? spiritual well‐being in the 3 days before death ? patient awareness at 3 and 1 week to death ? grief at 90 to 120 days after death ? caregiver post bereavement psychological well‐being in first 90 to 120 days after death (use of medication for anxiety and depression, increased drinking) |

↑ receipt of social services ↑ general counselling in study period ↑ paperwork assistance ↑ analgesics prescribed and taken at 1 week to death (increased in hospital‐based intervention vs. other groups) ↑ oral route of analgesics ↓ analgesic consumption on a pro order ↓ aggressive interventions (radiotherapy, surgery, chemo or hormonal therapy) ↓ diagnostic tests (blood tests, x‐rays, scans) ↓ respiratory support interventions (oxygen, respiratory therapy) ↓ radiotherapy for patients with primary brain cancer or brain metastases 0 general counselling in last 2 weeks before death Ø legal/financial counselling Ø help getting services Ø self care training Ø caregiver post‐bereavement absenteeism from work in first 90‐120 days after death Ø analgesics prescribed and taken at 3 weeks to death Ø level of analgesics used Ø mean daily OME consumption Ø thoracentesis Ø palliative radiation therapy for patients with bone metastases with bone pain ? institutional days ? physician and outpatient visits ? home nursing visits ? home health/home worker visits ? hours of direct informal care caregiver post‐bereavement healthcare use (physician visits, hospitalisation in first 90 to 120 days after death) |