Abstract

Introduction

Oesophagogastric cancers are known to spread rapidly to locoregional lymph nodes and by transcoelomic spread to the peritoneal cavity. Staging laparoscopy combined with peritoneal cytology can detect advanced disease that may not be apparent on other staging investigations. The aim of this study was to determine the current value of staging laparoscopy and peritoneal cytology in light of the ubiquitous use of computed tomography in all oesophagogastric cancers and the addition of positron emission tomography in oesophageal cancer.

Methods

All patients undergoing staging laparoscopy for distal oesophageal or gastric cancer between March 2007 and August 2013 were identified from a prospectively maintained database. Demographic details, preoperative staging, staging laparoscopy findings, cytology and histopathology results were analysed.

Results

A total of 317 patients were identified: 159 (50.1%) had gastric adenocarcinoma, 136 (43.0%) oesophageal adenocarcinoma and 22 (6.9%) oesophageal squamous carcinoma. Staging laparoscopy revealed macroscopic metastases in 36 patients (22.6%) with gastric adenocarcinoma and 16 patients (11.8%) with oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Positive peritoneal cytology in the absence of macroscopic peritoneal metastases was identified in a further five patients with gastric adenocarcinoma and six patients with oesophageal adenocarcinoma. There was no significant difference in survival between patients with macroscopic peritoneal disease and those with positive peritoneal cytology (p=0.219).

Conclusions

Staging laparoscopy and peritoneal cytology should be performed routinely in the staging of distal oesophageal and gastric cancers where other investigations indicate resectability. Currently, in our opinion, patients with positive peritoneal cytology should not be treated with curative intent.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Oesophageal cancer, Cancer staging, Laparoscopy

There are over 15,000 new cases of oesophageal or gastric cancer diagnosed in the UK each year.1 Oesophagogastric cancers tend to spread rapidly to locoregional lymph nodes and by transcoelomic spread to the peritoneal cavity. The presence of peritoneal metastases is a major prognostic indicator, making curative treatment impossible and limiting survival.

Current guidelines recommend that patients with a diagnosis of oesophageal cancer should be staged with computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen and pelvis.2 In patients where CT has not demonstrated any distant metastatic disease, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and positron emission topography CT (PET-CT) are performed. Patients with gastric cancer are staged with CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, with EUS being used in selected cases. The sensitivity of CT in detecting small volume metastatic disease continues to improve and this has been further augmented by PET-CT.3 Despite this, peritoneal metastases occurring by transcoelomic spread may not be apparent using these imaging modalities.4

Staging laparoscopy has been used to assess the peritoneal cavity in lower oesophageal, junctional and gastric cancers. It allows further assessment of the primary tumour, examination for small volume intraperitoneal metastatic disease or ascites and the collection of peritoneal washings for cytological evaluation.

Peritoneal cytology identifies free malignant cells in the peritoneum. It is thought that these cells are present in the peritoneal cavity as a result of cell shedding from the primary tumour where it involves the serosa.5–8 However, positive peritoneal cytology has also been observed in patients with T1 and T2 tumours when it is believed that perforating lymphatic channels may explain the presence of malignant cells in the peritoneal cavity.9

Importantly, positive peritoneal cytology has been shown repeatedly to be an independent poor prognostic indicator in gastric and oesophageal cancers.5,7,9–12 As such, positive peritoneal cytology has been classified as M1 disease in the most recent update on TNM (tumour, lymph nodes, metastasis) classification of gastric cancers.13

The aim of this study was to determine the proportion of patients with oesophagogastric cancers in whom staging laparoscopy and peritoneal fluid cytological assessment alters their management as well as to assess the impact of peritoneal disease on survival.

Methods

Consecutive patients presenting to two hospitals between March 2007 and August 2013 with a potentially resectable primary distal oesophageal, junctional or gastric cancer who had no evidence of metastases on CT and PET-CT were included in the study. Unresectability was based on previously described CT and EUS criteria.14–16

Laparoscopy was completed using a three-port technique with the abdominal viscera being inspected in a systematic fashion. Between 150ml and 500ml of warm 0.9% sodium chloride was instilled into the peritoneal cavity and stimulated externally before being aspirated from the pelvis and submitted for cytological evaluation.

Following multidisciplinary discussion, all patients with no evidence of macroscopic peritoneal disease and negative peritoneal cytology were offered surgical resection with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy if they were deemed fit. Those patients with peritoneal metastases or positive peritoneal cytology alone were treated with palliative chemotherapy if there were no contraindications based on performance status, co-morbidities or patient wishes.

Information including age at diagnosis, sex, tumour location, histology, date of laparoscopy, macroscopic laparoscopic findings and cytology result were collected from a contemporaneously maintained database. Tumours involving the gastro-oesophageal junction were classified as oesophageal tumours in accordance with TNM classification.13 Survival was calculated from date of laparoscopy and status determined from a national electronic database. Data were censored at death or 24 March 2014.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS® version 22 (IBM, New York, US). Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the logrank test. The incidence of peritoneal disease in different tumour locations was compared using the chi-squared test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 317 patients who had no evidence of distant metastases on CT and PET-CT underwent staging laparoscopy with peritoneal cytology. This included 159 gastric and 136 oesophageal (including junctional) adenocarcinomas. There were a further 22 patients who had a squamous cell oesophageal carcinoma involving the distal oesophagus; these were excluded from our analysis. The mean age was 68 years and 225 patients (70.9%) were male. No patients were lost to follow-up.

No patients died as a direct result of laparoscopy while one patient with adhesions due to previous surgery had a laparoscopy converted to a laparotomy because of a bowel injury caused at laparoscopy. No other morbidities linked to laparoscopy were identified.

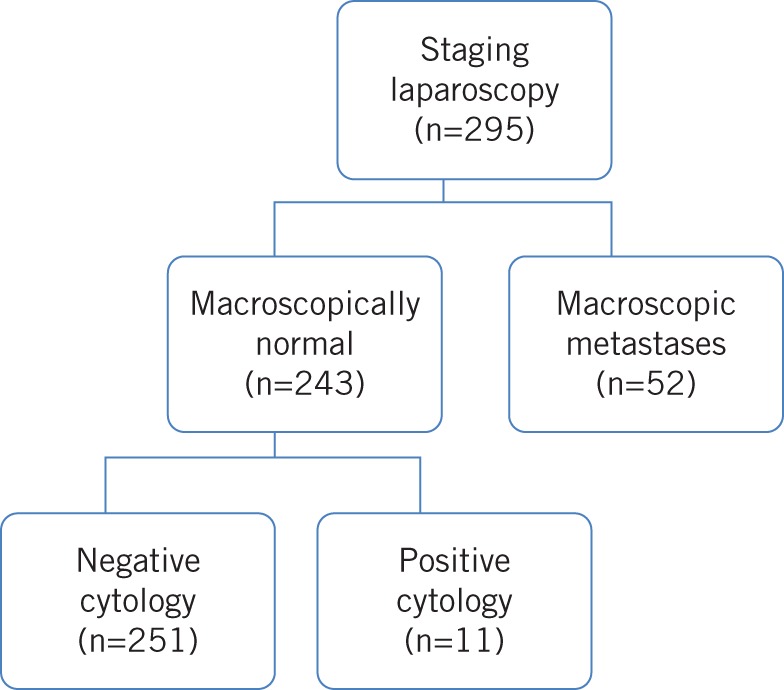

At laparoscopy, 52 (17.6%) of the 295 patients analysed had overt peritoneal disease that was confirmed histologically. These patients were not offered surgical resection. This included 36 (22.6%) of the 159 patients with gastric cancer and 16 (11.8%) of the 136 patients with an adenocarcinoma involving the oesophagus or gastro-oesophageal junction.

The remaining 243 patients had no evidence of macroscopic metastases at the time of staging laparoscopy. Of this group, 11 patients were identified as having positive peritoneal cytology.

In total, staging laparoscopy altered patient management in 63 cases (21.4%) where CT, PET-CT and EUS had indicated resectability (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

The outcomes of patients undergoing staging laparoscopy

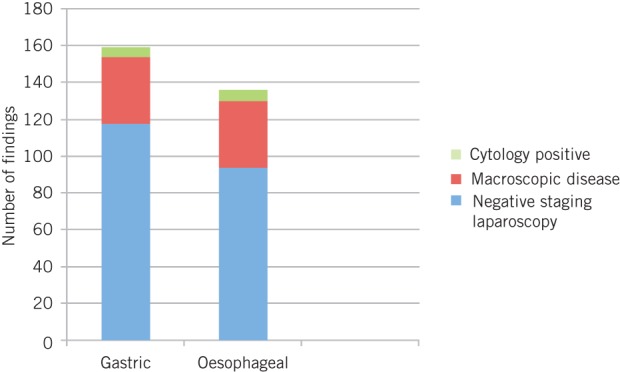

When all patients with oesophageal and junctional cancers are combined, there is a significantly lower incidence of overt peritoneal disease compared with the gastric cancer group (χ2=5.972, df=1, p=0.015). There is, however, no significant difference in the incidence of positive peritoneal cytology between the oesophageal and gastric group (χ2=0.328, df=1, p=0.567) (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Laparoscopy and cytology findings by tumour site

Of those patients who had evidence of macroscopic disease, 35 of 52 (67.3%) went on to have palliative chemotherapy. In the group of patients who had positive cytology, only 10 out of 11 patients proceeded to palliative chemotherapy. There was no significant difference in terms of the proportion of patients proceeding to have palliative chemotherapy between these groups (χ2=2.478, df=1, p=0.115).

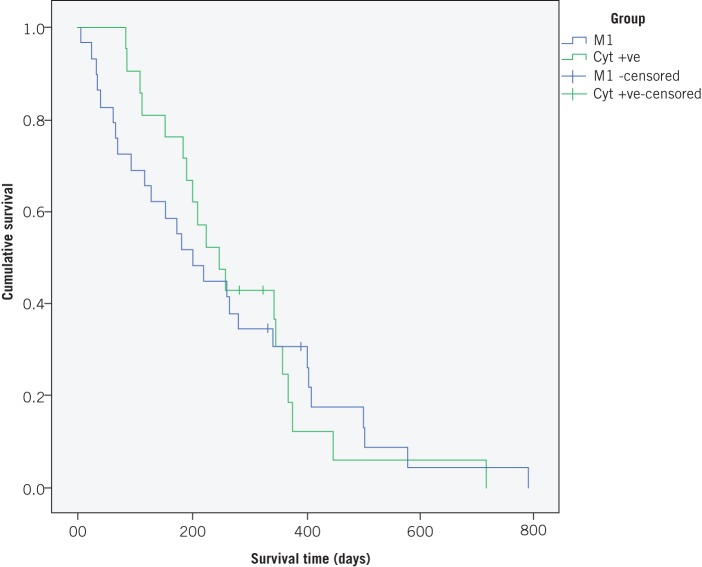

The median survival for patients with macroscopic peritoneal disease at staging laparoscopy was 208 days (95% confidence interval [CI]: 142–273 days). The median survival in the group with positive cytology alone was 368 days (95% CI: 330–405 days). There was no significant difference in survival between these two groups (p=0.219) (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with overt peritoneal metastases (M1) and cytology only positive (Cyt +ve)

Discussion

Despite advances in the quality of imaging modalities, it is clear that staging laparoscopy remains an important and useful tool in staging oesophagogastric cancers. Staging laparoscopy alone altered patient management in 17.6% (52/295) of patients. These were patients who otherwise would have undergone unnecessary neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by an ‘open and close’ laparotomy. The additional use of peritoneal cytology identified a further 4.5% (11/243) of patients who would have otherwise undergone a resection for incurable disease.

While improving the sensitivity of CT and PET-CT in diagnosing overt peritoneal disease may reduce the number of unnecessary staging laparoscopies performed, it will not help in identifying those patients with positive peritoneal cytology alone.

The treatment of patients with positive peritoneal cytology in the absence of macroscopic metastases has not yet been firmly established.17 The majority of previous studies have focused on gastric cancer with little being known about oesophageal cancer. A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials investigating the use of intraperitoneal chemotherapy as an adjunct to surgery and systemic chemotherapy in gastric cancer showed a survival benefit at one, two and three years with no significant improvement in five-year survival compared with surgery combined with systemic chemotherapy alone.18 This certainly seems an attractive option and appears logical. It does, however, carry a higher rate of morbidity than standard treatment in a subgroup of patients who already have a poor prognosis.

In our series, no patients with positive peritoneal cytology had a resection. Mezhir et al have suggested a treatment algorithm for patients with positive peritoneal cytology in gastric cancer, involving chemotherapy for a period of 6–12 months with subsequent restaging.19 If there is no evidence of disease progression, a further staging laparoscopy with peritoneal cytology is performed. Patients who converted to negative peritoneal cytology were considered for surgical resection if a further staging laparoscopy at 3–6 months confirmed the absence of peritoneal disease. They concluded that surgery was of limited benefit in these patients.

Other studies have demonstrated a greater role for surgery. Okabe et al reported a median survival of 43 months in 22 patients who had surgical resection following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for peritoneal disease in gastric cancer compared with 10 months without surgery (p<0.001).20 Several other reports have shown only a limited role for radical resection and cytoreductive surgery combined with intraperitoneal chemotherapy.21,22

Lee et al have suggested that selected patients with gastric cancer and positive peritoneal cytology should be offered a resection.23 Stratified analysis according to node category of patients with positive peritoneal cytology who had a resection showed that those with stage N0–2 tumours had significantly better survival than patients with N3 disease (median 26.0 months vs 15.0 months) (p=0.004).

Another approach that has shown promising results is the use of large volume peritoneal lavage with saline in addition to surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. This approach was associated with significantly better survival and a significantly lower rate of local recurrence than surgery alone or surgery with intraperitoneal chemotherapy.24

The rate of positive peritoneal cytology in the absence of macroscopic disease appears to vary quite considerably in the literature. Most investigators collect peritoneal washings at the time of attempted curative resection, which may have had an impact on the result owing tumour handling. However, the rate of 4.59% in our study is similar to another study also using laparoscopy to obtain cytological samples.25

The small numbers of patients with positive peritoneal cytology alone in this study make it difficult to make any definite conclusions. Nevertheless, there does not appear to be a significant difference in survival in patients with macroscopic peritoneal disease compared with those with positive peritoneal cytology. This supports the findings of previous research and would suggest that treatment with curative intent ought not to be attempted in patients with positive peritoneal cytology.25 The best form of palliation for these patients remains undetermined.

Despite the apparent value of staging laparoscopy in identifying incurable disease, there appears to be considerable variability in its use. The 2013 National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit has shown that only 57% of patients with potentially curative gastric or Siewert type II/III cancers had a staging laparoscopy.26 This represents a considerable number of patients who would have proceeded to have unnecessary neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by an ‘open and close’ laparotomy or resection with little or no survival benefit.

Conclusions

Staging laparoscopy should be performed routinely in patients with gastric, junctional and distal oesophageal cancers where other investigations have indicated resectability. Taking peritoneal washings for cytological evaluation augments staging laparoscopy further. Although the numbers were small, there was no significant difference in survival between patients with overt peritoneal metastases and those with positive peritoneal cytology alone. As such, we recommend that patients with positive peritoneal cytology should not be treated with curative intent. Further studies are needed to fully evaluate the role of intraperitoneal chemotherapy and cytoreductive surgery in this subgroup.

Acknowledgement

The material in this paper was presented at the International Surgical Congress of the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland held in Harrogate, May 2014.

References

- 1. Cancer Stats: Key Stats. Cancer Research UK. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/keyfacts/ (cited January 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allum WH, Griffin SM, Watson A, Colin-Jones D. Guidelines for the management of oesophageal and gastric cancer. Gut 2002; 50(Suppl 5): v1–v23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wong WL, Chambers RJ. Role of PET/PET CT in the staging and restaging of thoracic oesophageal cancer and gastro-oesophageal cancer: a literature review. Abdom Imaging 2008; 33: 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burbidge S, Mahady K, Naik K. The role of CT and staging laparoscopy in the staging of gastric cancer. Clin Radiol 2013; 68: 251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burke EC, Karpeh MS, Conlon KC, Brennan MF. Peritoneal lavage cytology in gastric cancer: an independent predictor of outcome. Ann Surg Oncol 1998; 5: 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iitsuka Y, Kaneshima S, Tanida O et al. Intraperitoneal free cancer cells and their viability in gastric cancer. Cancer 1979; 44: 1,476–1,480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ribeiro U, Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Zilberstein B et al. Does the intraoperative peritoneal lavage cytology add prognostic information in patients with potentially curative gastric resection? J Gastrointest Surg 2006; 10: 170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ribeiro U, Gama-Rodrigues JJ, Bitelman B et al. Value of peritoneal lavage cytology during laparoscopic staging of patients with gastric carcinoma. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1998; 8: 132–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosenberg R, Nekarda H, Bauer P et al. Free peritoneal tumour cells are an independent prognostic factor in curatively resected stage IB gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg 2006; 93: 325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bentrem D, Wilton A, Mazumdar M et al. The value of peritoneal cytology as a preoperative predictor in patients with gastric carcinoma undergoing a curative resection. Ann Surg Oncol 2005; 12: 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bando E, Yonemura Y, Takeshita Y et al. Intraoperative lavage for cytological examination in 1,297 patients with gastric carcinoma. Am J Surg 1999; 178: 256–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Doki Y, Kabuto T, Ishikawa O et al. Does pleural lavage cytology before thoracic closure predict both patient’s prognosis and site of cancer recurrence after resection of esophageal cancer? Surgery 2001; 130: 792–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sobin L, Gospodarowicz M, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 7th edn. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Halvorsen RA, Thompson WM. CT of esophageal neoplasms. Radiol Clin North Am 1989; 27: 667–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Halpert RD, Feczko PJ. Role of radiology in the diagnosis and staging of gastric malignancy. Endoscopy 1993; 25: 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Caletti GC, Ferrari A, Fiorino S et al. Staging of esophageal carcinoma by endoscopy. Endoscopy 1993; 25: 2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miyashiro I, Takachi K, Doki Y et al. When is curative gastrectomy justified for gastric cancer with positive peritoneal lavage cytology but negative macroscopic peritoneal implant? World J Surg 2005; 29: 1,131–1,134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coccolini F, Cotte E, Glehen O et al. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer. Meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014; 40: 12–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mezhir JJ, Shah MA, Jacks LM et al. Positive peritoneal cytology in patients with gastric cancer: natural history and outcome of 291 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17: 3,173–3,180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Okabe H, Ueda S, Obama K et al. Induction chemotherapy with S-1 plus cisplatin followed by surgery for treatment of gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination. Ann Surg Oncol 2009; 16: 3,227–3,236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hall JJ, Loggie BW, Shen P et al. Cytoreductive surgery with intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2004; 8: 454–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim KW, Chow O, Parikh K et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with gastric cancer, and the role for surgical resection, cytoreductive surgery, and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Am J Surg 2014; 207: 78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee SD, Ryu KW, Eom BW et al. Prognostic significance of peritoneal washing cytology in patients with gastric cancer. Br J Surg 2012; 99: 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kuramoto M, Shimada S, Ikeshima S et al. Extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage as a standard prophylactic strategy for peritoneal recurrence in patients with gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg 2009; 250: 242–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nath J, Moorthy K, Taniere P et al. Peritoneal lavage cytology in patients with oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg 2008; 95: 721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit 2013. London: RCS; 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]