Abstract

Objective. Chronic pain and progressive loss of physical function with AS may adversely affect health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The objective of this study was to assess the 5-year data regarding spinal mobility, physical function and HRQoL in patients with AS who participated in the Adalimumab Trial Evaluating Long-term Efficacy and Safety for AS (ATLAS) study.

Methods. Patients received blinded adalimumab 40 mg or placebo every other week for 24 weeks, then open-label adalimumab for up to 5 years. Spinal mobility was evaluated using linear BASMI (BASMIlin). BASDAI, total back pain, CRP, BASFI, Short Form-36 and AS quality of life (ASQoL) were also assessed. Correlations between BASMIlin and clinical, functional and ASQoL outcomes after 12 weeks and after 5years of adalimumab exposure were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation. Associations were further analysed using multivariate regression.

Results. Three hundred and eleven patients received ≥1 dose of adalimumab; 125 of the 208 patients originally randomized to adalimumab received treatment for 5 years. Improvements in BASMIlin were sustained through 5 years, with a mean change of –0.6 from baseline in the population who completed 5 years of treatment with adalimumab. Improvements in disease activity, physical function and ASQoL were also sustained through 5 years. BASMIlin was significantly correlated with all evaluated clinical outcomes (P < 0.001). The highest correlation was with BASFI at 12 weeks (r = 0.52) and at 5 years (r = 0.65). Multivariate regression analysis confirmed this association (P < 0.001).

Conclusion. Treatment with adalimumab for up to 5 years demonstrated sustained benefits in spinal mobility, disease activity, physical function and HRQoL in patients with active AS. Spinal mobility was significantly associated with short- and long-term physical function in these patients.

Trial registration: Clinicaltrials.gov; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ NCT00085644.

Keywords: anti-TNF drugs, ankylosing spondylitis, spinal mobility, health-related quality of life, physical function

Rheumatology key messages.

Clinical improvements observed with adalimumab were sustained for up to 5 years in AS patients.

Correlation between spinal mobility and physical function was significant both short term and long term in AS patients.

Introduction

AS is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects the axial skeleton, peripheral joints and entheses, primarily of the spine and SI joints [1]. Symptoms of AS include back pain, loss of spinal mobility, joint stiffness and fatigue. The progressive nature of AS can result in complete fusion of the spine, putting patients at risk of vertebral fractures [2]. Progressive AS can also cause significant functional impairment, reductions in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [3, 4], reduced capacity for work [5, 6] and substantial direct and indirect costs for the patient and the health care system [7].

TNF antagonists (etanercept, infliximab, golimumab and adalimumab) have demonstrated clinical efficacy in short-term and long-term clinical trials [8–25]. For adalimumab, long-term effectiveness data for patients treated for up to 5 years are now available from the Adalimumab Trial Evaluating Long-term Efficacy and Safety for AS (ATLAS) study. ATLAS was a Phase 3, randomized, 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial with an open-label extension for up to 5 years, assessing efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with active AS [21]. This study demonstrated that significantly more patients treated with adalimumab achieved Assessment in SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) 20 response compared with those treated with a placebo within 2 weeks of treatment initiation. A high ASAS20 response rate (89%) was maintained in patients completing 5 years of treatment [26].

Considering the lifelong consequences of AS on spinal mobility and HRQoL, long-term data on the impact of anti-TNF treatment on these outcomes are needed. The ATLAS trial has shown that adalimumab treatment resulted in short-term (12–24 weeks) improvements in physical function, disease activity, general health and HRQoL compared with placebo in patients with AS [21, 27]. Moreover, improvements in these parameters were maintained through 3 years of treatment [8]. However, sustained improvements in spinal mobility after adalimumab treatment as measured by the BASMI have only been reported for 2 years of adalimumab treatment [23]. The current report provides an assessment of the long-term improvement in spinal mobility using the more sensitive linear BASMI (BASMIlin) [28], as well as physical function and HRQoL through 5 years of adalimumab treatment in patients with active AS. In addition, this analysis evaluated the association of spinal mobility and clinical, functional and HRQoL outcomes.

Methods

Patients and study design

Patients were ≥18 years of age, fulfilled the modified New York criteria for AS [29] and had ≥2 of the following disease activity criteria: BASDAI score ≥4, morning stiffness ≥1 h and VAS for total back pain ≥4 (on a scale of 0–10). Full details of the inclusion/exclusion criteria have been previously published [21]. Patients were randomized 2:1 to receive adalimumab (AbbVie, North Chicago, IL, USA) 40 mg or placebo s.c. every other week for 24 weeks. Further details of the study design have been published [21]. Patients in the randomized portion of the trial were eligible to continue treatment in an open-label extension study in which patients received open-label adalimumab 40 mg every other week or weekly for up to 5 years, as previously described [23, 26]. Clinic visits during the first 6months of the open-label period occurred every 6 weeks. Visits were every 12–16 weeks for the remainder of the open-label extension period. All research was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional ethics review board and ethics committee approval was obtained, and each patient provided written informed consent.

Outcome measures

Spinal mobility in the original controlled, double-blind period of ATLAS was assessed using BASMI2, a composite index (scale 0–10) based on categorical scores on a scale of 0–2 for five clinical measurements: cervical rotation (in degrees), anterior lumbar flexion, lumbar side flexion, intermalleolar distance and tragus-to-wall distance (all measured in centimetres) [30]. BASMIlin was calculated using the data collected for the BASMI2. BASMIlin is a composite measure, with a total score ranging from 0 to 10 based on a linear assessment-to-score of the five clinical measurements. The BASMIlin has demonstrated a greater sensitivity to change compared with the BASMI2 [28]. A higher score indicates worse spinal mobility. Disease activity was assessed using BASDAI (0–10 cm VAS) [31], total back pain (0–10 cm VAS) and CRP (mg/dl). Physical function was assessed using the BASFI (0–10 cm VAS) and the Short Form-36 (SF-36) physical component score (PCS; 0–50) [32]. HRQoL was assessed using the AS quality of life (ASQoL) and SF-36 PCS [33]. A decrease of ≥1.8 points in ASQoL (where lower scores represent an increase in AS-specific quality of life) [34] or an increase of ≥3.0 points in the SF-36 PCS (where higher scores represent better health status) [27] have been previously identified as the minimum important difference (MID) for these HRQoL measures. Details of the questions posed, domains assessed and possible ranges for these instruments have been published [8].

Statistical analysis

The mean observed scores or values at baseline, week 12 and years 1, 3 and 5 were determined for BASMIlin and its components, BASDAI, total back pain, CRP, BASFI, SF-36 PCS and ASQoL. Values and scores from baseline up to week 12, and years 1, 3 and 5 were time-averaged. Analyses were conducted for all patients who received ≥1 dose of adalimumab (blinded or open-label), termed the any adalimumab population. Baseline for this analysis was defined as the last observation before the first dose of adalimumab and included patients originally enrolled in the placebo arm but who switched to treatment with open-label adalimumab. An additional analysis of efficacy endpoints at baseline, week 12, and years 1, 3 and 5 was conducted using data from only those patients who were originally randomized to adalimumab and who completed 5 years of the study, termed the 5-year adalimumab completer population. At the year 5 time point, the any adalimumab and the 5-year adalimumab completer populations were identical, as no patients in the any adalimumab group who had been randomized to receive placebo during the double-blind period reached a full 5 years of adalimumab treatment. Values reported are those observed (i.e. no imputations were made for missing data). Correlation coefficients between BASMIlin and BASDAI, total back pain, BASFI, SF-36 PCS and ASQoL outcomes after 12 weeks and after 5 years of adalimumab exposure were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation. All assumptions for the Spearman’s rank order correlation coefficient were verified, and correlation coefficients were tested for statistical significance (P < 0.05). Interpretation of the correlation coefficients were 0.00−0.29, little or no correlation; 0.30−0.49, weak; 0.50−0.69, moderate; 0.70−0.89, strong and 0.90−1.00, very strong [35]. As linear regression analysis of BASMIlin showed significant association with each of the covariates (BASDAI, total back pain, BASFI, SF-36 PCS and ASQoL), multivariate regression analysis was performed by first including all five explanatory variables in the model and subsequently dropping and adding variables to come up with the best model, based on adjusted R2 values. Although the BASDAI showed significant association with BASMIlin in the multivariate regression model, it was excluded from the final model due to multicollinearity between BASDAI and BASFI. BASFI was retained in the model due to its stronger association with BASMIlin. The final model included age and BASFI as covariates for explaining BASMIlin.

Results

Patients

Of the 315 randomized patients (adalimumab, n = 208; placebo, n = 107), 311 received ≥ 1 dose of adalimumab, either blinded or open-label (any adalimumab population; see Supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology Online). From this population, 65% (202 of the 311) completed the 5-year study. Withdrawal of consent (n = 37) and adverse events (n = 38) were the most common reasons for discontinuation during the 5 years of the study. The median [mean (s.d.)] duration of exposure to adalimumab in the any adalimumab population was 4.8 years [3.9 (1.6) years]. Of the original 208 patients who were randomized to treatment with adalimumab, 125 patients (60%) completed 5 years of treatment (the 5-year adalimumab completer population). A significant number of patients (n = 77) initially received placebo for 6 months and thus were exposed to adalimumab for only 4.5 years; although these patients completed the study, they were not included in the population for analysis of 5-year exposure (n = 125). In the any adalimumab population, 82 of the 311patients (26%) received ≥ 7 doses in the last 70days of treatment, indicating weekly dosing. Of the 202 patients who received adalimumab at any time and who completed 5 years in the study, 29 patients (14%) received ≥ 7 doses in the last 70 days of treatment.

Baseline clinical characteristics for patients treated during the double-blind period have been previously reported [21]. Demographics and disease state characteristics for the 5-year adalimumab completer population (n = 125) at baseline (i.e. assessment prior to first dose of adalimumab in the double-blind period) were similar to the any adalimumab study population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics and disease state of patients who received adalimumab

| Any adalimumab populationa n = 311 | Population who completed 5 years of adalimumab treatmentb n = 125 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (s.d.), years | 42.3 (11.6) | 42.8 (12.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 233 (74.9) | 101 (80.8) |

| White, n (%) | 299 (96.1) | 121 (96.8) |

| Disease duration, mean (s.d.), years | 11.0 (9.5) | 11.9 (10.4) |

| BASDAI score, 0–10 cm VAS | 6.3 (1.7) | 6.2 (1.8) |

| BASFI score, 0–10 cm VAS | 5.4 (2.2) | 5.2 (2.1) |

| BASMIlin 0–10 | 4.4 (1.7)c | 4.3 (1.7) |

| SF-36 PCS, 0–50 | 32.5 (8.0)d | 33.2 (8.2)e |

| ASQoL, 0–18 | 10.3 (4.3) | 9.9 (4.3) |

| Total back pain, 0–10 cm VAS | 6.5 (2.1) | 6.4 (2.1) |

Data are mean (s.d.) unless otherwise indicated. aPatients who received ≥ 1 dose of adalimumab. Baseline was the last observation before the first dose of adalimumab. bPatients initially randomized to adalimumab and who had a total of 5 years of adalimumab exposure during the study. cn = 309. dn = 307. en = 124. ASQoL: AS quality of life questionnaire; BASMIlin: linear BASMI; PCS: physical component score; SF-36: Short Form-36 Health Survey.

Spinal mobility

Both BASMI (as previously described by van der Heijde et al. [21]) and BASMIlin (Table 2) were significantly improved compared with placebo after 12 weeks of treatment with adalimumab (P < 0.001). In the any adalimumab population, improvement in spinal mobility as measured by the composite BASMIlin score was sustained through 5years of treatment with adalimumab (Table 2). In the 5-year adalimumab completer population, BASMIlin scores were 4.3 (s.d. 1.7) at baseline and 3.7 (1.7) after 5 years of treatment with adalimumab, a mean change of –0.6 (Table 2; P < 0.001 change from baseline at year 5). In this 5-year adalimumab completer population, the individual BASMI components of lumbar side flexion, cervical rotation and intramalleolar distance demonstrated significant improvements from baseline at year 5 (P < 0.001 for all comparisons change from baseline at year 5) and appeared to continue to improve over the course of the 5-year observation period (Table 2). For patients in the any adalimumab population with weekly dosing of adalimumab in the last 70 days of treatment, BASMIlin scores were 4.7 (1.7) at baseline and 4.3 (1.5) at year 5, a mean change of –0.4 (P = 0.06).

Table 2.

Spinal mobility–BASMIlin and components over 5 years

| Duration of exposure to adalimumab |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Baseline | Week 12 | Year 1 | Year 3 | Year 5 |

| BASMIlin composite, scale 0–10 | |||||

| Any adalimumab populationa | 4.4 (1.7) n = 309 | 4.2 (1.7) n = 309 | 4.0 (1.7) n = 282 | 3.8 (1.7) n = 233 | 3.7 (1.7) n = 124 |

| 5-year adalimumab completersb | 4.3 (1.7) n = 125 | 4.1 (1.7) n = 124 | 3.8 (1.7) n = 125 | 3.7 (1.7) n = 124 | 3.7 (1.7) n = 124 |

| Lumbar flexion, cm | |||||

| Any adalimumab populationa | 4.0 (3.5) n = 311 | 4.0 (3.0) n = 309 | 4.0 (2.7) n = 282 | 4.0 (2.6) n = 233 | 4.0 (2.4) n = 124 |

| 5-year adalimumab completersb | 4.1 (3.5) n = 125 | 4.2 (3.2) n = 124 | 4.3 (2.9) n = 125 | 4.1 (2.7) n = 124 | 4.0 (2.4) n = 124 |

| Lumbar side flexion, cm | |||||

| Any adalimumab populationa | 9.5 (5.4) n = 307 | 10.2 (5.3) n = 306 | 10.9 (5.5) n = 282 | 11.5 (5.6) n = 233 | 12.0 (5.6) n = 123 |

| 5-year adalimumab completersb | 9.8 (5.5) n = 122 | 10.7 (5.4) n = 121 | 11.8 (5.6) n = 125 | 12.0 (5.5) n = 124 | 12.0 (5.6) n = 123 |

| Cervical rotation, degrees | |||||

| Any adalimumab populationa | 46.3 (22.1) n = 310 | 48.2 (20.7) n = 307 | 51.4 (20.4) n = 282 | 53.9 (20.6) n = 233 | 54.9 (20.8) n = 125 |

| 5-year adalimumab completersb | 46.7 (20.7) n = 125 | 48.7 (20.3) n = 122 | 52.1 (20.5) n = 125 | 54.1 (20.5) n = 124 | 54.9 (20.8) n = 125 |

| Intermalleolar distance, cm | |||||

| Any adalimumab populationa | 93.6 (26.1) n = 305 | 97.1 (25.3) n = 305 | 101.2 (25.8) n = 280 | 104.0 (22.5) n = 232 | 106.2 (22.4) n = 124 |

| 5-year adalimumab completersb | 95.9 (23.3) n = 124 | 100.3 (24.7) n = 123 | 104.4 (27.1) n = 125 | 106.0 (23.3) n = 124 | 106.2 (22.4) n = 124 |

| Tragus-to-wall distance, cm | |||||

| Any adalimumab populationa | 15.8 (6.0) n = 309 | 15.6 (5.7) n = 307 | 15.6 (5.5) n = 282 | 15.5 (5.7) n = 233 | 15.7 (6.1) n = 125 |

| 5-year adalimumab completersb | 15.9 (6.2) n = 124 | 15.9 (6.0) n = 123 | 15.8 (5.8) n = 125 | 15.6 (6.0) n = 124 | 15.7 (6.1) n = 125 |

Data are mean (s.d.). Decreased BASMIlin composite scores indicate improvement. aPatients who received ≥ 1 dose of adalimumab. Baseline was the last observation before the first dose of adalimumab. bPatients initially randomized to adalimumab and who had a total of 5 years of adalimumab exposure during the study. BASMIlin: linear BASMI.

Disease activity and physical function

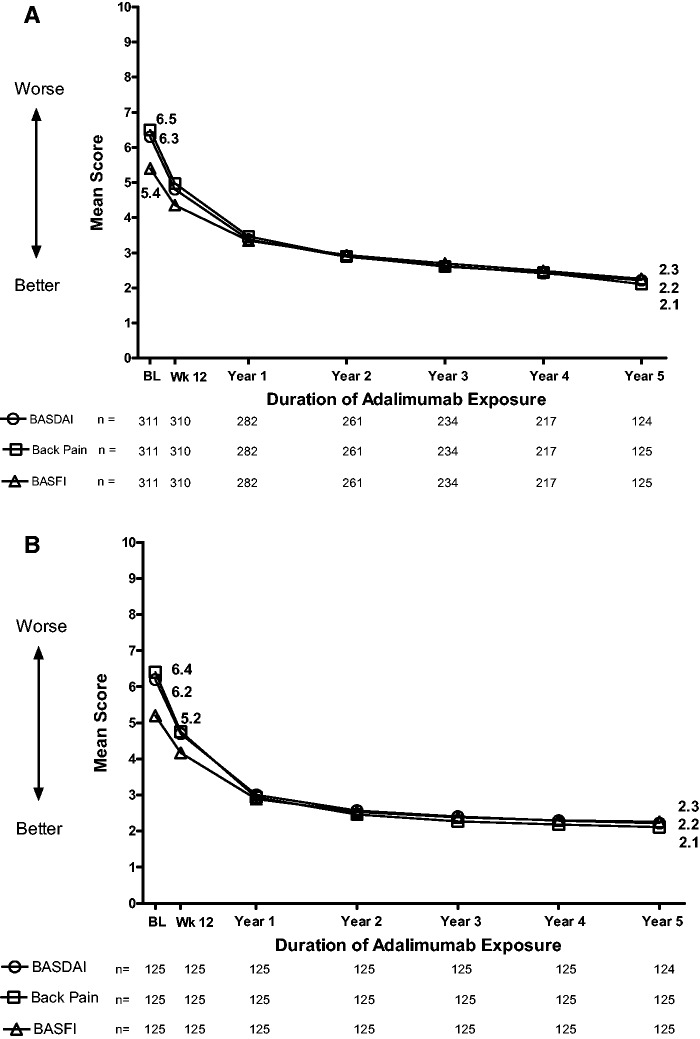

In the any adalimumab population, improvements in disease activity (BASDAI), total back pain and function (BASFI) were sustained over 5 years (Fig. 1A). CRP levels showed the same pattern, with mean values of 1.20 mg/dl at week 12 (n = 308), 0.71 mg/dl at year 1 (n = 282), 0.56 mg/dl at year 3 (n = 233), 0.52 mg/dl at year4 (n = 217) and 0.50 mg/dl at year 5 (n = 125). In the 5-year adalimumab completer population, improvements in disease activity, total back pain and function were observed over the 5-year period (Fig. 1B). CRP levels in the 5-year adalimumab completer population were 1.30 mg/dl at week 12, 0.54 mg/dl at year 3, 0.51 mg/dl at year 4 and 0.50 mg/dl at year 5.

Fig. 1.

Mean BASDAI, total back pain and BASFI scores over time

Analysis in the (A) any adalimumab population and (B) 5-year adalimumab completer population.

Health-related quality of life

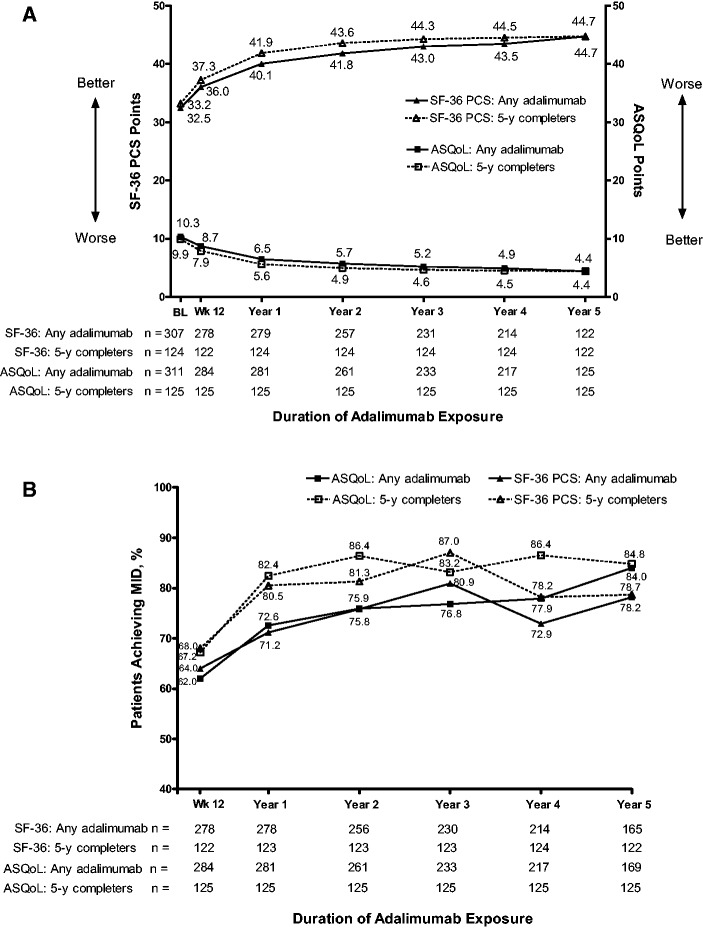

Improvement in the SF-36 PCS and ASQoL was maintained through 5 years of treatment with adalimumab in both the any adalimumab and the 5-year adalimumab completer populations (Fig. 2A). The proportion of patients who achieved the MID for SF-36 PCS increased numerically from 64.0% of patients (178 of 278) at week12 to 78.2% of patients (129 of 165) at year 5 in the any adalimumab population, and from 68.0% of patients (83 of 122) at week 12 to 78.7% of patients (96 of 122) at year 5 in the 5-year adalimumab completer population (Fig. 2B). The proportion of patients who achieved the MID for ASQoL increased from 62.0% of patients (176 of 284) at week 12 to 84.0% of patients (142 of 169) at year 5 in the any adalimumab population, and from 67.2% of patients (84 of 125) at week 12 to 84.8% of patients (106 of 125) at year 5 in the 5-year adalimumab completer population (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Quality of life measures

(A) Mean SF-36 PCS and ASQoL over time; (B) percentage of patients reaching the minimum important difference (MID) for SF-36 PCS and ASQoL over time. The MID was defined as a change of at least –1.8 for ASQoL and at least 3.0 for SF-36 PCS. ASQoL: AS quality of life; SF-36 PCS: Short Form-36 physical component score.

Association of spinal mobility with disease activity, function and HRQoL

BASMIlin was significantly correlated with each evaluated disease, function or HRQoL measure at week 12 and year5 (P < 0.001 for each; Table 3). The strongest correlation was observed for BASFI at week 12 and year 5 (r = 0.52 and r = 0.65, respectively). A multivariate regression model confirmed a significant association between BASMIlin and BASFI, as well as between BASMIlin and age (P < 0.001; Table 4). None of the other variables tested in the multivariate regression model had significant associations with BASMIlin.

Table 3.

Correlation of BASMIlin with disease activity, physical function and quality of life measuresa

| Week 12, n = 309 |

Year 5, n = 124 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | n | r b | P-valuec | n | r b | P-valuec | |

| BASDAI | 308 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 123 | 0.41 | <0.001 | |

| Total back pain | 308 | 0.25 | <0.001 | 124 | 0.42 | <0.001 | |

| BASFI | 308 | 0.52 | <0.001 | 124 | 0.65 | <0.001 | |

| SF-36 PCS | 278 | −0.33 | <0.001 | 121 | −0.40 | <0.001 | |

| ASQoL | 282 | 0.30 | <0.001 | 124 | 0.33 | <0.001 | |

aAnalysis is for the any adalimumab population. bInterpretation of the correlation coefficients: 0.00–0.29, little or no correlation; 0.30–0.49, weak; 0.50–0.69, moderate; 0.70–0.89, strong; and 0.90–1.00, very strong. cSignificant P-value suggests that a non-zero correlation may be present between corresponding variables. ASQoL: AS quality of life; BASMIlin: linear BASMI; SF-36 PCS: Short Form-36 physical component score.

Table 4.

Multivariate regression analysis between BASMIlin and other clinical and demographic variables at year 5a

| BASMIlin (dependent variable) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimate (s.e.) | t-value | P-value | |

| Intercept | 0.852 (0.47) | 1.82 | 0.07 |

| Age, years | 0.046 (0.01) | 3.99 | 0.0001 |

| BASFI 0–10 cm VAS | 0.44 (0.06) | 6.75 | <0.0001 |

| R2 = 0.44 | |||

| Adjusted R2 = 0.43 | |||

aAnalysis is for the population who completed 5 years of adalimumab treatment. BASMIlin: linear BASMI.

Discussion

There is a growing body of evidence that treatment of AS with anti-TNF agents provides long-term benefits. The progressive restriction of physical function typically experienced by patients with AS negatively affects their HRQoL. Slowing or halting this progressive loss of function over the long term is thus an important goal of AS therapy. This current study is the first to report data for up to 5 years in terms of improvement in spinal mobility with adalimumab. Adalimumab treatment resulted in improvements in spinal mobility, as measured by the composite BASMIlin score, which appear to be due to improvements in lumbar side flexion, intermalleolar distance and cervical rotation components. In contrast, lumbar flexion and tragus-to-wall flexion measurements remained similar to baseline throughout the study. These improvements in spinal mobility are consistent with shorter-term findings with adalimumab [23] and long-term findings with other anti-TNF agents [36–38].

The baseline BASMIlin scores in the current analysis were higher than the baseline BASMI2 score previously reported by van der Heijde et al. [21] for the ATLAS study population originally randomized to treatment with adalimumab. However, this is not surprising as mean status scores for BASMI2 have been shown to be lower compared with BASMIlin scores [28, 39].

The current analysis demonstrated that improvements in physical function and disease activity were maintained over 5 years. Consistent with these data, HRQoL improvements observed after 12 and 24 weeks of adalimumab treatment [27] were sustained till the end of the 5-year study. By year 5, most patients remaining in the study had reached the MID for both ASQoL and SF-36 PCS. These results were observed despite the finding that progression of structural damage in AS (as determined by radiographs) does not appear to be inhibited by 2 years of adalimumab treatment [40]. Radiographic data with longer follow-up are not available. Multivariate regression analyses in a study of infliximab treatment demonstrated that HRQoL in AS is determined by physical function and disease activity [41]. In addition, multivariate regression showed that physical function is dependent on spinal mobility and disease activity; the degree of spinal mobility, in turn, is determined by irreversible structural damage and reversible inflammation of the spine [41, 42]. However, the association between structural damage and spinal mobility is highly variable among individual patients [15]. This discordance may be due to the influence of spinal inflammation on spinal mobility [42]. Thus, maintaining a high HRQoL by improving physical function and reducing disease activity is an achievable goal for patients with AS treated with anti-TNF therapy.

The second objective of the current analysis was to determine whether spinal mobility correlated with other AS clinical, functional and HRQoL outcomes. Significant correlations between BASMIlin and BASDAI, total back pain, SF-36 PCS and ASQoL were observed, although they were weak. The weakness of association between these variables was further confirmed by multivariate regression analysis, in which these measures were not a statistically significant contributory factor to BASMIlin. The BASMIlin correlated best with BASFI at both week 12 and at year5. This moderate correlation suggests that improvements in spinal mobility lead to enhanced physical function throughout extended treatment with adalimumab. The multivariate regression analysis confirmed the significant nature of the positive association between spinal mobility and physical function. In a previous study of 70 patients with AS who completed 6 months of pamidronate therapy, changes in the BASMI2 also significantly correlated with changes in BASFI (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.44; P < 0.001) [43].

The main strength of this study is the duration of the long-term follow-up. ATLAS is the largest long-term clinical trial of anti-TNF treatment of AS to date. Limitations of long-term analyses include the fact that patients for whom efficacy is suboptimal are less likely to remain in the study, enriching the continuing study population with patients who are doing relatively well. Also, the open-label nature of the extension period may have resulted in bias.

Conclusion

Treatment of active AS with adalimumab for up to 5 years resulted in sustained benefits in spinal mobility, physical function and HRQoL. Spinal mobility was correlated with patient-reported function, both early in the course of adalimumab treatment and after 5 years of therapy, suggesting improvements in mobility result in enhanced long-term physical function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sumati A. Rao for her contributions to the development of the manuscript. Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Erin P. Scott, PhD, of Complete Publication Solutions, LLC; this support was funded by AbbVie.

Funding: This work (NCT00085644) was supported by AbbVie, who was involved in study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; and reviewing and approving this publication. AbbVie provided funding for editorial and medical writing support.

Disclosure statement: M.B. has received consulting fees, research grants, and/or speaking fees from AbbVie, BMS, Schering-Plough, UCB, Sanofi, Pfizer and Wyeth. S.S.R. is an employee of AbbVie and holds AbbVie stocks. A.L.P. is a full-time employee of AbbVie and owns stocks. D.v.d.H. has received consulting fees, research grants, and/or speaking fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor (now Janssen Biotech), Chugai, Eli Lilly, GSK, Merck, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, UCB and Wyeth, and is owner of Imaging Rheumatology. H.K. is a full-time employee of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock or stock options. J.S. has received honoraria for giving advice or as a member of a speaker’s bureau from AbbVie, Merck, Novartis, UCB and Pfizer. D.G.H. has received speaker honoraria from Takeda and Pfizer. G.D. has been a speaker for AbbVie, BMS, Pfizer and Takeda. S.K. is a former contractor for AbbVie. P.J.M. has received research grants, consulting fees and/or speaking fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen Idec, BMS, Celgene, Covagen, Crescendo, Novartis, Janssen, Genentech, Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer and UCB. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology Online.

References

- 1.Gran JT, Husby G. The epidemiology of ankylosing spondylitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1993;22:319–34. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(05)80011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alaranta H, Luoto S, Konttinen YT. Traumatic spinal cord injury as a complication to ankylosing spondylitis. An extended report. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20:66–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barkham N, Kong KO, Tennant A, et al. The unmet need for anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology. 2005;44:1277–81. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis JC, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, Woolley JM. Reductions in health-related quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and improvements with etanercept therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:494–501. doi: 10.1002/art.21330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boonen A, Chorus A, Miedema H, et al. Withdrawal from labour force due to work disability in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:1033–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.11.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boonen A, Chorus A, Miedema H, et al. Employment, work disability, and work days lost in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a cross sectional study of Dutch patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:353–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boonen A, van der Linden SM. The burden of ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2006;78:4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Heijde DM, Revicki DA, Gooch KL, et al. Physical function, disease activity, and health-related quality-of-life outcomes after 3 years of adalimumab treatment in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R124. doi: 10.1186/ar2790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baraliakos X, Listing J, Rudwaleit M, et al. Safety and efficacy of readministration of infliximab after longterm continuous therapy and withdrawal in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:510–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, et al. Two year maintenance of efficacy and safety of infliximab in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:229–34. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.025130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun J, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, et al. Persistent clinical response to the anti-TNF-alpha antibody infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis over 3 years. Rheumatology. 2005;44:670–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis JC, van der Heijde DM, Braun J, et al. Sustained durability and tolerability of etanercept in ankylosing spondylitis for 96 weeks. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1557–62. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.035105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Listing J, et al. Outcome of patients with active ankylosing spondylitis after two years of therapy with etanercept: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging data. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:856–63. doi: 10.1002/art.21588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Heijde D, Han C, DeVlam K, et al. Infliximab improves productivity and reduces workday loss in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:569–74. doi: 10.1002/art.22097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wanders A, Landewe R, Dougados M, et al. Association between radiographic damage of the spine and spinal mobility for individual patients with ankylosing spondylitis: can assessment of spinal mobility be a proxy for radiographic evaluation? Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:988–94. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.029728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, Listing J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine and the sacroiliac joints in ankylosing spondylitis and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis during treatment with etanercept. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1305–10. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.032441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis JC, Jr, Van Der Heijde D, Braun J, et al. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3230–6. doi: 10.1002/art.11325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calin A, Dijkmans BA, Emery P, et al. Outcomes of a multicentre randomised clinical trial of etanercept to treat ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1594–600. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.020875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun J, Landewe R, Hermann KG, et al. Major reduction in spinal inflammation in patients with ankylosing spondylitis after treatment with infliximab: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1646–52. doi: 10.1002/art.21790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, et al. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1187–93. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Heijde D, Kivitz A, Schiff MH, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2136–46. doi: 10.1002/art.21913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Heijde D, Pangan AL, Schiff MH, et al. Adalimumab effectively reduces the signs and symptoms of active ankylosing spondylitis in patients with total spinal ankylosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1218–21. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.082529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Heijde D, Schiff MH, Sieper J, et al. Adalimumab effectiveness for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis is maintained for up to 2 years: long-term results from the ATLAS trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:922–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.087270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun J, Deodhar A, Inman RD, et al. Golimumab administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks in ankylosing spondylitis: 104-week results of the GO-RAISE study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:661–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.154799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inman RD, Davis JC, Jr, Heijde D, et al. Efficacy and safety of golimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3402–12. doi: 10.1002/art.23969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, et al. Early response to adalimumab predicts long-term remission through 5 years of treatment in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:700–6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis JC, Jr, Revicki D, van der Heijde DM, et al. Health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis treated with adalimumab: results from a randomized controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1050–7. doi: 10.1002/art.22887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Feldtkeller E. Proposal of a linear definition of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) and comparison with the 2-step and 10-step definitions. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:489–93. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.074724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkinson TR, Mallorie PA, Whitelock HC, et al. Defining spinal mobility in ankylosing spondylitis (AS). The Bath AS Metrology Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1694–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ware JEJ, Snow KK, Kosinski M. SF-36 Health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doward LC, Spoorenberg A, Cook SA, et al. Development of the ASQoL: a quality of life instrument specific to ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:20–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Jordan K, Dziedzic K, Dawes PT. Disease-specific, patient-assessed measures of health outcome in ankylosing spondylitis: reliability, validity and responsiveness. Rheumatology. 2002;41:1295–302. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.11.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy LG, Jenkinson TR, Mallorie PA, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: the correlation between a new metrology score and radiology. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:767–70. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/34.8.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baraliakos X, Listing J, Fritz C, et al. Persistent clinical efficacy and safety of infliximab in ankylosing spondylitis after 8 years—early clinical response predicts long-term outcome. Rheumatology. 2011;50:1690–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heldmann F, Brandt J, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, et al. The European ankylosing spondylitis infliximab cohort (EASIC): a European multicentre study of long term outcomes in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:672–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin-Mola E, Sieper J, Leirisalo-Repo M, et al. Sustained efficacy and safety, including patient-reported outcomes, with etanercept treatment over 5 years in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:238–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Inman RD, et al. Comparison of three methods for calculating the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index in a randomized placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1919–22. doi: 10.1002/acr.21771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Heijde D, Salonen D, Weissman BN, et al. Assessment of radiographic progression in the spines of patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with adalimumab for up to 2 years. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R127. doi: 10.1186/ar2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machado P, Landewe R, Braun J, et al. A stratified model for health outcomes in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1758–64. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.150037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Machado P, Landewe R, Braun J, et al. Both structural damage and inflammation of the spine contribute to impairment of spinal mobility in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1465–70. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.124206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jauregui E, Conner-Spady B, Russell AS, Maksymowych WP. Clinimetric evaluation of the bath ankylosing spondylitis metrology index in a controlled trial of pamidronate therapy. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2422–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.