Abstract

Objective

Data from the 2003 and 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) reflect the increasing prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and treatment by health care providers. This report updates these prevalence estimates for 2011 and describes temporal trends.

Method

Weighted analyses were conducted with 2011 NSCH data to estimate prevalence of a parent-reported ADHD diagnosis, current ADHD, current medication treatment, ADHD severity, and mean age of diagnosis for US children aged 4–17 years and among demographic subgroups. A history of ADHD diagnosis (2003—2011) as well as current ADHD and medication treatment prevalence (2007–2011) were compared using prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Results

In 2011, 11% of children aged 4–17 years had ever received an ADHD diagnosis (6.4 million children). Among those with a history of ADHD diagnosis, 83% were reported as currently having ADHD (8.8%); 69% of children with current ADHD were taking medication for ADHD (6.1%, 3.5 million children). A parent-reported history of ADHD increased by 42% from 2003—2011. Prevalence of a history of ADHD, current ADHD, medicated ADHD and moderate/severe ADHD increased significantly from 2007 estimates. Prevalence of medicated ADHD increased by 28% from 2007—2011.

Conclusions

An estimated two million more US children aged 4–17 years had been diagnosed with ADHD in 2011, compared to 2003. More than two-thirds of those with current ADHD were taking medication for treatment in 2011. This suggests an increasing burden of ADHD in the US. Efforts to further understand ADHD diagnostic and treatment patterns are warranted.

Keywords: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, stimulant, medication, prevalence, epidemiology

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurobehavioral disorder with childhood onset.1 Children with ADHD experience clinically significant functional impairment across settings (for example at home, in school, and with friends), resulting in higher rates of unintentional injury, emergency room visits, peer problems, and academic failure.2–7 Approximately one-third of children diagnosed with ADHD retain the diagnosis into adulthood, supporting the recognition of ADHD as a chronic health condition.8

Best practices for diagnosing and treating ADHD exist and include conducting a clinical diagnostic evaluation, incorporating information from multiple respondents (e.g., parents, child, teachers, child care staff) and across multiple settings (e.g., home, school, child care), and evaluating the child for co-occurring conditions.9,10 ADHD medication has long been used to effectively treat ADHD symptoms of impulsivity, inattention, and hyperactivity and is the single-most effective treatment for reducing ADHD symptoms.11,12 High-quality behavioral interventions can also improve functional outcomes of select children with ADHD, but may not be as broadly available across the US.13,14

Characterizing the evolving epidemiology of ADHD informs the public health impact of diagnosis and treatment within communities, allows for tracking changes over time, informs service use and needs, and provides a context for interpreting the impact of health alerts extending from adverse event reporting systems.15–18 Population-based epidemiological estimates of ADHD can come from a variety of sources. Analyses of insurance claims data have documented steady increases in prevalence of ADHD diagnoses between 2001 and 2010,19,20 however studies based on claims data are not necessarily representative of the uninsured or under-insured. A recent, large-scale community-based study from four school districts across two states suggests that the prevalence among elementary-aged children is 9–11%21; however community-based studies are resource-intensive and are often not generalizable to other communities. Large-scale surveys of parents that ask about clinician-diagnosed conditions provide an important cross-sectional picture of the impact of disorders, including ADHD, and can be repeated over time for surveillance purposes. Parent surveys can also be used to estimate both national and state-based prevalence of conditions.

Since 1996, parent reports of health care provider-diagnosed ADHD in childhood have been collected by nationally-representative health surveys, beginning with the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).22 The reports of a diagnosis by a health care provider is a proxy for underlying ADHD, asking parents “Has a doctor or other health care provider ever told you that your child had attention deficit disorder (ADD) or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)?” This report of an ADHD diagnosis was included in the 2003, 2007, and 2011 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), which is a periodic parent survey of the physical and emotional health of US children, 0–17 years of age.23,24 Increases in parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and medication treatment have been documented using data from NHIS and NSCH; average annual increases in parent-reported ADHD diagnosis ranged from 3%–6% per year since the late 1990s.25–27

Based on data from the 2007 NSCH, an estimated 9.5% of children 4–17 years of age had been diagnosed with ADHD; 78% of those children were characterized by their parents as having current ADHD, representing 7.2% (4.1 million) of school-aged children.27 The estimated prevalence increased by 22% from 2003–2007 with an average annual increase of 5.5% per year from 2003–2007. Increases in prevalence were greatest among groups with historically lower rates of ADHD: older teens, Hispanics, and children who spoke a primary language other than English. Two-thirds of those with current ADHD were taking medication in 2007. ADHD medication treatment increased with ADHD severity. Nearly 1 in 20 (4.8%) of US children 4–17 years of age (2.7 million children) were taking ADHD medication in 2007, which is consistent with a 2008 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey estimate of 5.1% among children 6–12 years of age.28

Data from the most recent NSCH allow for updated estimates of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and treatment, and inspection of trends in these estimates over time. Based on previous reports, average annual growth rates of 3–6% for parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and a commensurate increase in parent-reported ADHD medication treatment were expected.

Method

The NSCH is a national cross-sectional, random-digit-dialed telephone survey conducted in 2003–2004 (“2003”), 2007–2008 (“2007”), and 2011–2012 (“2011”).23,24,29 The NSCH uses the sampling frame of the National Immunization Survey30; because of the rise in the prevalence of cell-phone-only households, the 2011 NSCH added a sample of cell-phone numbers. Between February 2011 and June 2012, 95,677 interviews were completed, resulting in landline and cell-phone interview completion rates of 54.1% and 41.2%, respectively, and a 23.0% overall response rate.29 Sample weights were utilized to adjust for unequal probability of selection of households and children, nonresponse, and the underlying demographic distribution of US non-institutionalized children. The survey questions pertaining to ADHD diagnosis and treatment are included as a supplement to this article. A responding parent or guardian (referred to hereafter as “parent”) was asked questions about one randomly selected child (aged 0–17 years) in the household. Analyses were conducted in SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.0 (RTI International; Cary, NC) to account for the complex survey design and application of sample weights.

At all three time points, parents were asked if “a doctor or other health care provider ever told you that [child] had Attention Deficit Disorder or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, that is, ADD or ADHD?” In 2007 and 2011, parents who reported a history of ADHD were asked whether the child currently had ADHD, and in 2011, they were asked the age at which the child was diagnosed. Parents reporting current ADHD also described the severity of ADHD (mild, moderate or severe). In each survey year, a question was included asking about current medication treatment for ADHD, however a different subset of parents were asked this question in 2003 as compared to subsequent surveys. In 2003, parents who reported that their child had ever received a diagnosis were asked about current medication treatment, while in 2007 and 2011, only parents reporting current ADHD were asked about current medication treatment; this prohibited direct comparisons of medication for ADHD across the three surveys. Data allowed for direct comparisons of ever-diagnosed ADHD (2003—2011), current ADHD (2007—2011), ADHD severity (2007–2011), and current medication for ADHD (2007—2011). Independent of ADHD diagnosis, all parents were asked if their child had received treatment or counseling from a mental health professional in the past 12 months.

Data Analysis

For the 2011 survey data, estimated prevalence of a history of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis (ever-diagnosed), current ADHD, and current medication treatment were calculated for children aged 4–17 years, and compared across demographic subgroups using prevalence ratios (PRs). Mean age of diagnosis was calculated overall and contrasted with severity using a Wald F-test.

The demographic groups and subgroups were comparable to those used in the previous reports describing the 2003 and 2007 data27,31 to allow direct comparison of the estimates over time. Estimated prevalence of ever-diagnosed ADHD in 2011 was compared to 2003 and 2007 NSCH estimates using PRs; differences in rate of change over time was tested with a Wald F-test comparing the combination of yearly indicator regression coefficients. Estimates of current ADHD and current medication treatment from 2011 were compared to 2007 using PRs and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Demographic subgroup differences for change over time were tested by a Wald F-test on an interaction term. Parent-report of treatment or counseling by a mental health professional was combined with medication treatment to estimate ADHD treatment prevalence among children with current ADHD; the percentage of those with a current ADHD diagnosis reported to be in treatment was compared between 2007 and 2011.

Results

All ADHD survey indicators extended from parent-reported data for children aged 4–17 years; for brevity, the term “parent-reported” and age (4–17 years) is excluded as a qualifier of the relevant estimates that follow.

2011 Ever-diagnosed and Current ADHD Prevalence Estimates and Demographic Patterns

In 2011, the estimated prevalence of ever-diagnosed ADHD among children was 11.0%, representing 6.4 million children nationwide (Table 1). Among children with ever-diagnosed ADHD, 82.3% had current ADHD resulting in an estimated national prevalence of 8.8% among children (5.1 million nationwide).

Table 1.

Weighted prevalence estimates of parent-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis by a health care provider among children aged 4–17 years by sociodemographic characteristics – National Survey of Children’s Health, United States, 2011

|

Ever-diagnosed with ADHD n = 76,015 respondents |

Current ADHD n = 75,840 respondents |

Current ADHD and Current Medication for ADHD n = 76,003 respondents |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | % | 95% CIa | PRb | % | 95% CIa | PRb | % | 95% CIa | PRb |

| Overall | 76,015 | 11.0 | 10.5–11.5 | 8.8 | 8.4–9.3 | 6.1 | 5.7–6.5 | |||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 39,314 | 15.1 | 14.3–15.9 | 2.24 | 12.1 | 11.4–12.8 | 2.36 | 8.4 | 7.8–9.0 | 2.30 |

| Female | 36,701 | 6.7 | 6.2–7.3 | 1.00 | 5.5 | 5.0–6.0 | 1.00 | 3.7 | 3.3–4.1 | 1.00 |

| Age (%) | ||||||||||

| 4–10 years of age | 36,219 | 7.7 | 7.2–8.3 | 1.00 | 6.8 | 6.2–7.4 | 1.00 | 4.9 | 4.5–5.4 | 1.00 |

| 11–14 years of age | 21,409 | 14.3 | 13.3–15.4 | 1.85 | 11.4 | 10.5–12.4 | 1.69 | 7.9 | 7.2–8.8 | 1.63 |

| 15–17 years of age | 18,387 | 14.0 | 12.9–15.2 | 1.81 | 10.2 | 9.2–11.3 | 1.51 | 6.4 | 5.7–7.3 | 1.32 |

| Highest Educ. in Household (%) | ||||||||||

| <HS | 4,453 | 8.5 | 7.2–9.9 | 0.78 | 6.9 | 5.7–8.2 | 0.79 | 4.2 | 3.4–5.2 | 0.70 |

| 12 Years, HS Graduate | 11,569 | 13.3 | 12.1–14.6 | 1.23 | 11.0 | 9.9–12.2 | 1.27 | 7.7 | 6.8–8.7 | 1.29 |

| >HS | 58,550 | 10.8 | 10.3–11.4 | 1.00 | 8.6 | 8.1–9.2 | 1.00 | 6.0 | 5.6–6.4 | 1.00 |

| Race (%) | ||||||||||

| White | 54,927 | 12.2 | 11.5–12.8 | 1.00 | 9.8 | 9.2–10.4 | 1.00 | 7.1 | 6.6–7.6 | 1.00 |

| Black | 7,615 | 11.9 | 10.6–13.4 | 0.98c | 9.5 | 8.3–10.9 | 0.98c | 5.7 | 4.8–6.7 | 0.80 |

| Other | 11,450 | 7.2 | 6.3–8.1 | 0.59 | 5.8 | 5.1–6.7 | 0.60 | 3.5 | 2.9–4.3 | 0.50 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 9,676 | 6.9 | 5.9–8.1 | 0.56 | 5.5 | 4.6–6.6 | 0.56 | 3.1 | 2.5–3.9 | 0.44 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 64,799 | 12.3 | 11.8–12.9 | 1.00 | 9.9 | 9.4–10.4 | 1.00 | 7.0 | 6.6–7.5 | 1.00 |

| Primary Language in Home (%) | ||||||||||

| English | 70,522 | 12.4 | 11.9–13.0 | 4.66 | 10.0 | 9.5–10.5 | 5.04 | 7.0 | 6.6–7.4 | 7.38 |

| Any other language | 5,455 | 2.7 | 1.9–3.7 | 1.00 | 2.0 | 1.3–3.0 | 1.00 | 0.9 | 0.6–1.5 | 1.00 |

| Federal Poverty Level (%)d | ||||||||||

| ≤100% | 10,974 | 12.9 | 11.7–14.2 | 1.30 | 10.9 | 9.8–12.1 | 1.38 | 6.8 | 6.0–7.8 | 1.21 |

| >100% to ≤200% | 13,500 | 11.8 | 10.7–12.9 | 1.18 | 9.4 | 8.4–10.5 | 1.19 | 6.5 | 5.7–7.4 | 1.16† |

| >200% | 51,541 | 10.0 | 9.4–10.6 | 1.00 | 7.9 | 7.3–8.5 | 1.00 | 5.6 | 5.2–6.1 | 1.00 |

| Any Health Care Coverage (%) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 72,511 | 11.3 | 10.8–11.8 | 9.2 | 8.7–9.6 | 6.3 | 6.0–6.7 | |||

| Medicaid/SCHIPe (public) | 20,313 | 14.4 | 13.5–15.4 | 1.53 | 11.9 | 11.0–12.9 | 1.58 | 8.1 | 7.4–8.8 | 1.51 |

| Non-Medicaid (private) | 51,440 | 9.4 | 8.9–10.0 | 1.00 | 7.5 | 7.0–8.1 | 1.00 | 5.3 | 4.9–5.8 | 1.00 |

| No | 3,380 | 6.4 | 5.0–8.2 | 0.68 | 4.1 | 3.0–5.5 | 0.54 | 2.3 | 1.4–3.6 | 0.42 |

| Region | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 13,620 | 10.1 | 9.2–11.2 | 1.26 | 8.1 | 7.2–9.1 | 1.27 | 5.4 | 4.7–6.1 | 1.42 |

| Midwest | 17,870 | 12.1 | 11.3–13.0 | 1.50 | 10.0 | 9.3–10.8 | 1.57 | 7.1 | 6.5–7.8 | 1.88 |

| South | 25,327 | 12.6 | 11.8–13.4 | 1.56 | 10.1 | 9.3–10.9 | 1.58 | 7.3 | 6.7–8.0 | 1.94 |

| West | 19,198 | 8.1 | 7.0–9.3 | 1.00 | 6.4 | 5.4–7.5 | 1.00 | 3.8 | 3.1–4.6 | 1.00 |

CI = Confidence Interval

PR = Prevalence Ratio

PR not significant at α=0.05 level

Includes multiply imputed values for 9.4% of sample for which household income was missing.

SCHIP: State Children’s Health Insurance Program

ADHD diagnosis (ever and current) was significantly associated (p < 0.05 based on X2 statistics) with every demographic indicator studied. Ever-diagnosed ADHD was higher among boys (15.1%) than girls (6.7%) and increased with age (Table 1). The highest point estimates were among boys (15.1%), children 11 and older (11–14 years: 14.3%, 15–17 years: 14.0%), and children with public health care coverage (14.4%). Prevalence was higher for black and white children compared to those of other races; the prevalence among Hispanics was half that of non-Hispanics. Those living in households where English is the primary language were more than four times as likely to have been diagnosed as those living in households speaking another primary language. Prevalence was highest among children from households with 12 years (high school graduate) of education, compared to households with more or less education. Children living below 200% of the federal poverty level had a higher prevalence than children from higher income families. Ever-diagnosed ADHD was more common among children with health care coverage than those without coverage, and among those with public coverage than with private coverage. Ever-diagnosed ADHD was lowest in the West, compared to other US regions.

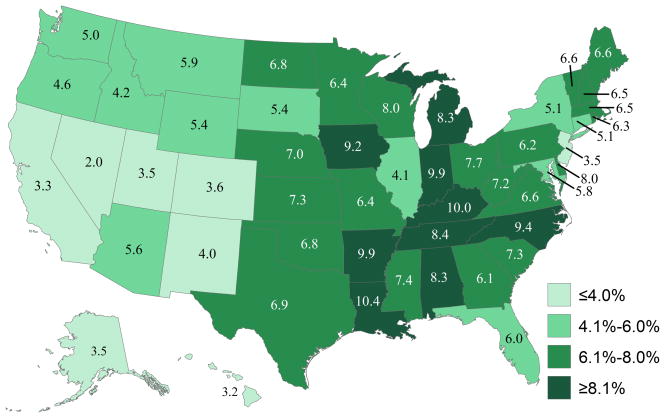

The demographic and state-based patterns for current ADHD were generally consistent with those observed for ever-diagnosed ADHD, although current ADHD estimates were approximately 20–25% lower than ever-diagnosed estimates (Table 1). State-based estimates of current ADHD ranged from 4.2% in Nevada to 14.6% in Arkansas and 14.8% in Kentucky (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Weighted prevalence estimates of parent-reported current attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among children aged 4–17 years by state – United States, 2011

Among children with current ADHD, the median age of diagnosis was 6.2 years (95% CI 6.1–6.4; mean=7.0, 95% CI 6.9–7.2). Age of diagnosis decreased with severity; children whose parents reported the child’s ADHD as “mild” were diagnosed at a median age of 7.0 years (95% CI 6.8–7.3; mean=7.8, 95% CI 7.5–8.1), compared to 6.1 (95% CI 5.8–7.3; mean=6.9, 95% CI 6.7–7.1) and 4.4 (95% CI 4.1–4.7; mean=5.1, 95% CI: 4.9–5.5) years for those with “moderate” and “severe” ADHD, respectively.

2011 Medication Treatment for Current ADHD

Estimated prevalence of medication treatment for ADHD among US children was 6.1% (3.5 million nationwide). Of those with a current ADHD diagnosis, 69.0% were taking ADHD medication. ADHD medication treatment estimates were significantly associated with every demographic indicator studied (p < 0.05 by X2statistics). The highest point estimates of parent-reported ADHD medication treatment were observed among boys (8.4%), whites (7.1%), non-Hispanics (7.0%), children living in households speaking English as the primary language (7.0%), children with public health care coverage (8.1%), and children living in the Midwest (7.1%) and South (7.3%; Table 1). After increasing with age from 4–10 years to 11–14 years, current medication treatment prevalence decreased slightly among children 15–17 years of age. Current medication treatment was lowest among children in households speaking a primary language other than English (0.9%). State-based estimates ranged from 2.0% in Nevada to 10.0% in Kentucky and 10.4% in Louisiana (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Weighted prevalence estimates of parent-reported current attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication treatment among children aged 4–17 years by state – United States, 2011

The proportion of children taking medication for ADHD increased with ADHD severity: 59.6% (95% CI 55.6–63.5) for “mild” ADHD, 73.3% (95% CI: 69.2–77.0) for “moderate” ADHD, and 82.4% (95% CI: 76.0–87.3) for “severe” ADHD. The percentage of children with current ADHD who received any treatment or counseling from a mental health professional was 51.0% (95% CI 48.4–53.7). The percentage of children receiving either medication for ADHD or mental health treatment was 82.5% (95% CI 80.5–84.4).

Trends in Parent-reported ADHD Indicators over Time

Ever-diagnosed and Current ADHD

Estimated prevalence of ever-diagnosed ADHD was 7.8%, 9.5%, and 11% in 2003, 2007, and 2011, respectively (Table 2). These estimates increased by 22% from 2003–2007 (average annual increase = 6%27) and 16% from 2007–2011 (average annual increase = 4%). The total increase from 2003–2011 was 42% (PR = 1.42, 95% CI 1.33–1.50; average annual increase = 5%). The only two demographic subgroups for which there was not a significant change in ever-diagnosed ADHD from 2003—2011 were multiracial/other race children and children without health care coverage. The magnitudes of increase (slopes) from 2003—2007 and 2007—2011 were equivalent for every subgroup studied, with the exception of the subgroup where the highest level of education was high school (F1, 39956=4.05, p<0.05) and children of multiracial/other races (F1,24866=7.3, p<0.01), in which the magnitudes of increase were smaller for 2007—2011 than 2003—2007. The greatest relative increases in ever-diagnosed ADHD from 2007—2011 were among children aged 11–14 years, children living in a household with an adult with more than a high school education, whites, and children living in the Midwest. The pattern in the proportion of children with ever-diagnosed ADHD differed over time as a function of age (F4, 228198=2.57, p=0.0359); ever-diagnosed ADHD increased from 2003 to 2011 for children 14 and under, but the growth leveled off for older children from 2007 to 2011 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Weighted prevalence estimates of parent-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis by a health care provider among children aged 4–17 yearsa by sociodemographic characteristics – National Survey of Children’s Health, United States, 2003, 2007, and 2011

| Ever-Diagnosed with ADHD | Current ADHD | Current ADHD and Current Medication for ADHD | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| 2003 | 2007 | 2011 | 2003–2011 | 2007–2011 | 2007 | 2011 | 2007–2011 | 2007 | 2011 | 2007–2011 | |||||

| % | % | % | PRb | 95% CIc | PRb | 95% CIc | % | % | PRb | 95% CIc | % | % | PRb | 95% CIc | |

| Overall | 7.8 | 9.5 | 11.0 | 1.42 | 1.33–1.50 | 1.16 | 1.08–1.24 | 7.2 | 8.8 | 1.23 | 1.13–1.33 | 4.8 | 6.1 | 1.28 | 1.16–1.41 |

| Sex | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 11.0 | 13.2 | 15.1 | 1.37 | 1.28–1.48 | 1.15 | 1.06–1.24 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 1.17 | 1.07–1.29 | 6.9 | 8.4 | 1.22 | 1.09–1.36 |

| Female | 4.4 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 1.52 | 1.36–1.71 | 1.19 | 1.04–1.37 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 1.38 | 1.19–1.59 | 2.5 | 3.7 | 1.46 | 1.24–1.72 |

| Age (%) | |||||||||||||||

| 4–10 years of age | 5.7 | 6.6 | 7.7 | 1.35 | 1.22–1.50 | 1.17 | 1.03–1.31 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 1.24 | 1.09–1.41 | 3.7 | 4.9 | 1.33 | 1.15–1.55 |

| 11–14 years of age | 9.8 | 11.2 | 14.3 | 1.46 | 1.32–1.61 | 1.28 | 1.14–1.43 | 8.6 | 11.4 | 1.33 | 1.17–1.51 | 6.3 | 7.9 | 1.26 | 1.08–1.47 |

| 15–17 years of age | 9.6 | 13.6 | 14.0 | 1.46 | 1.31–1.63 | 1.03 | 0.91–1.17 | 9.3 | 10.2 | 1.10 | 0.94–1.29 | 5.2 | 6.4 | 1.24 | 1.02–1.50 |

| Highest Educ. in Household (%) | |||||||||||||||

| <HS | 6.5 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 1.31 | 1.02–1.69 | 1.01 | 0.80–1.29 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 1.06 | 0.80–1.40 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 1.06 | 0.74–1.50 |

| 12 Years, HS Graduate | 8.6 | 12.2 | 13.3 | 1.55 | 1.37–1.75 | 1.09 | 0.94–1.26 | 9.0 | 11.0 | 1.22 | 1.03–1.43 | 5.9 | 7.7 | 1.30 | 1.07–1.58 |

| >HS | 7.6 | 8.7 | 10.8 | 1.43 | 1.33–1.54 | 1.24 | 1.14–1.35 | 6.7 | 8.6 | 1.29 | 1.17–1.42 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 1.32 | 1.18–1.48 |

| Race (%) | |||||||||||||||

| White | 8.6 | 9.9 | 12.2 | 1.42 | 1.32–1.52 | 1.23 | 1.14–1.34 | 7.5 | 9.8 | 1.31 | 1.19–1.43 | 5.1 | 7.1 | 1.37 | 1.24–1.53 |

| Black | 7.7 | 10.1 | 11.9 | 1.54 | 1.30–1.83 | 1.18 | 0.99–1.40 | 7.8 | 9.5 | 1.22 | 0.99–1.50 | 5.1 | 5.7 | 1.12 | 0.86–1.45 |

| Other | 6.6 | 9.2 | 7.2 | 1.09 | 0.86–1.37 | 0.78 | 0.63–0.97 | 7.2 | 5.8 | 0.81 | 0.64–1.04 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 0.81 | 0.59–1.11 |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||||||||||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 3.7 | 5.6 | 6.9 | 1.88 | 1.48–2.38 | 1.22 | 0.94–1.60 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 1.33 | 0.99–1.81 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 1.32 | 0.90–1.93 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 8.6 | 10.5 | 12.3 | 1.43 | 1.35–1.52 | 1.18 | 1.10–1.26 | 8.0 | 9.9 | 1.24 | 1.15–1.35 | 5.4 | 7.0 | 1.30 | 1.18–1.44 |

| Primary Language in Home (%) | |||||||||||||||

| English | 8.6 | 10.5 | 12.4 | 1.44 | 1.35–1.53 | 1.18 | 1.10–1.27 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 1.26 | 1.16–1.36 | 5.3 | 7.0 | 1.31 | 1.19–1.44 |

| Any other language | 1.3 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.10 | 1.33–3.33 | 1.15 | 0.72–1.85 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.10 | 0.61–1.97 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.08 | 0.49–2.38 |

| Federal Poverty Level (%)d | |||||||||||||||

| ≤100% | 9.3 | 11.6 | 12.9 | 1.39 | 1.21–1.61 | 1.11 | 0.96–1.29 | 9.2 | 10.9 | 1.18 | 1.00–1.39 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 1.09 | 0.88–1.34 |

| >100% to ≤200% | 7.9 | 10.3 | 11.8 | 1.49 | 1.31–1.70 | 1.14 | 0.97–1.33 | 7.7 | 9.4 | 1.22 | 1.03–1.46 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 1.40 | 1.14–1.71 |

| >200% | 7.3 | 8.6 | 10.0 | 1.37 | 1.27–1.48 | 1.16 | 1.06–1.28 | 6.5 | 7.9 | 1.22 | 1.09–1.36 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 1.30 | 1.14–1.47 |

| Any Health Care Coverage (%) | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | 8.1 | 9.8 | 11.3 | 1.40 | 1.31–1.49 | 1.15 | 1.07–1.24 | 7.6 | 9.2 | 1.21 | 1.11–1.31 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 1.25 | 1.13–1.37 |

| Medicaid/SCHIPe (public) | 10.8 | 13.6 | 14.4 | 1.33 | 1.21–1.47 | 1.06 | 0.95–1.18 | 10.9 | 11.9 | 1.10 | 0.97–1.24 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 1.08 | 0.93–1.24 |

| Non-Medicaid (private) | 7.0 | 8.1 | 9.4 | 1.36 | 1.25–1.47 | 1.17 | 1.06–1.28 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 1.23 | 1.10–1.37 | 4.1 | 5.3 | 1.31 | 1.15–1.49 |

| No | 4.9 | 6.7 | 6.4 | 1.32 | 0.96–1.81 | 0.96 | 0.67–1.37 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 1.11 | 0.74–1.65 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.31 | 0.71–2.42 |

| Region | |||||||||||||||

| Northeast | 7.4 | 9.4 | 10.1 | 1.38 | 1.20–1.58 | 1.08 | 0.92–1.27 | 7.4 | 8.1 | 1.09 | 0.91–1.30 | 4.5 | 5.4 | 1.18 | 0.94–1.48 |

| Midwest | 7.9 | 9.9 | 12.1 | 1.53 | 1.38–1.68 | 1.22 | 1.10–1.35 | 7.6 | 10.0 | 1.32 | 1.17–1.49 | 5.3 | 7.1 | 1.35 | 1.18–1.56 |

| South | 9.1 | 10.9 | 12.6 | 1.38 | 1.26–1.51 | 1.15 | 1.04–1.27 | 8.3 | 10.1 | 1.22 | 1.09–1.37 | 5.8 | 7.3 | 1.25 | 1.09–1.45 |

| West | 5.8 | 7.0 | 8.1 | 1.40 | 1.15–1.69 | 1.16 | 0.91–1.47 | 5.1 | 6.4 | 1.24 | 0.95–1.63 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 1.33 | 0.96–1.84 |

Analytic sample included 79,264 children in 2003, 73,123 children in 2007, and 76,015 children in 2011.

PR = Prevalence Ratio

CI = Confidence Interval

Federal poverty level; multiple imputations were used for 10.0% of 2003, 8.9% of 2007, 9.4% of 2011 for which household income was missing.

SCHIP: State Children’s Health Insurance Program

Current ADHD increased by 23%, from 7.2% to 8.8% from 2007–2011 (Table 2). The increases were reflected in significantly higher 2011 prevalence among children under 14 years, children from households with at least 12 years of education, whites, non-Hispanics, children living in households where English was a primary language, those living in households with incomes above 100% of poverty, children with health care coverage, and children living in the Midwest and South; the greatest relative increases were seen among girls, children 11–14 years of age, whites, and children living in the Midwest. Prevalence was statistically similar between 2007 and 2011 among those with public health care coverage, but increased significantly among children with private health care coverage. The increased prevalence of current ADHD among Hispanics did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06). The proportion of children with current ADHD among those with ever-diagnosed ADHD increased from 2007—2011, from 78.2% to 80.1% (X21=7.93, p<0.01). The distribution of ADHD severity shifted from 2007—2011 (mild: 46.7% vs. 41.4%, moderate: 39.5% vs. 43.1%, severe: 13.8% vs. 15.5%; X22=3.09, p<0.05). The pattern in the proportion of children reported to have current ADHD over time varied as a function of child race (F2, 142350=6.40, p=0.0017). Specifically, the proportion of children with current ADHD decreased among children of multiracial/other races whereas it increased among children of white or black races (Table 2).

Current Medication Treatment for ADHD and Treatment by a Mental Health Professional

ADHD medication treatment increased 28% from 2007—2011 from 4.8% to 6.1% (Table 2), an average annual increase of 7%. The proportion of children taking medication within strata of parent-reported severity was statistically similar in 2007 and 2011. Descriptively, the demographic groups with the greatest relative increases in current medication prevalence were females, 4–10 year olds, whites, children living above 100% of the Federal poverty level, and children living in the Midwest. The pattern in the proportion of children taking medication for ADHD varied as a function of child race (F2, 142676=5.59, p=0.0037; the proportion of children taking medication for ADHD decreased among children of multiracial/other races whereas it increased among children of white or black races (Table 2).

Although the prevalence of current mental health treatment or counseling among those with current ADHD remained similar from 2007—2011, the percentage of children who either received that treatment or were taking ADHD medication increased (78.8% to 82.5%; χ2=4.10, p<0.05), due to increases in ADHD medication treatment. Among those not receiving either of the two forms of treatment, 63.6% were reported as having mild ADHD (95% CI 57.8–69.1), 29.5% as moderate (95% CI 24.5–35.1), and 6.9% as severe (95% CI 4.4–10.5).

ADHD Prevalence and Medicated Prevalence Stratified by Age and Sex

Prevalence of ADHD diagnosis and current medication treatment for ADHD are presented by sex-stratified age across the three survey periods in Figure 3. Increasing prevalence over time can be seen from the growing size of the inverted pyramid, with a relatively consistent sex ratio for each indicator. Among boys, the 2003 prevalence of ever-diagnosed ADHD (outer bars) was less than 15%, regardless of age; in 2007, the estimates exceeded 15% for those 9–17, with the exception of 12-year-olds (13.9%); in 2011 the estimates exceeded 15% for those 10–17, and exceeded 20% for 11-year-olds and 14-year-olds. Among girls, the 2003 prevalence of ever-diagnosed ADHD (outer bars) increased from ages 4–8, then stabilized at 5–6% for those 9–17; in 2007 the prevalence increased with estimates ranging from 5.8% among 10-year-olds to 11.6% among 16-year-olds; in 2011 the prevalence ranged from just over 5% to just under 10% for all but 14-year-olds, for whom the estimated prevalence of ever-diagnosed ADHD was 11.8%.

Figure 3.

Weighted prevalence estimates (%) of parent-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis by a health care provider among children, by age and medication status – United States, 2003, 2007, and 2011

The medication treatment question was asked of parents reporting ever-diagnosed ADHD in 2003 and parents reporting current ADHD in 2007 and 2011. In 2003, medicated ADHD prevalence increased from ages 4–9, stabilized, and then decreased in the teen years for both sexes. Estimates of medicated ADHD increased in 2011, as compared to 2007 particularly among teen boys. In 2011, the highest medicated ADHD prevalence was among 11-year-old boys (13.3%). Among girls, medicated ADHD remained under 5% until 2011 when the estimates met or exceeded 5% for girls aged 9–10 and 14–15.

Discussion

The epidemiological profile for ADHD diagnosis and treatment continues to evolve. Based on parent-reported indicators of health care provider-diagnosed ADHD diagnosis and treatment, more than one in ten (11%) school-aged children had received an ADHD diagnosis by a health care provider by 2011, representing over 6.4 million children nationally. Nearly 1 in 5 high school boys and 1 in 11 high school girls had been diagnosed with ADHD. Of those with a history of ADHD, 83% had current ADHD in 2011 (8.8% nationwide) and 69% of these children (6.1% nationwide) were taking medication for ADHD. These estimates are all significantly higher than comparable 2007 estimates.27 Specifically, after a 22% increase in parent-reported history of ADHD diagnosis from 2003—2007, the prevalence increased another 16% from 2007—2011; a total increase of 42% from 2003—2011. Medicated ADHD among children living in the US increased by 27% from 2007—2011. Among children with a history of ADHD, proportionately more had current ADHD in 2011, as compared to 2007. Taken together, an estimated two million more American children were diagnosed with ADHD and a million more were taking ADHD medication in 2011 compared to 2003.

This study reveals a number of important and consistent demographic patterns for ADHD diagnosed by health care providers. Parent-report of ADHD diagnosis increased for most demographic subgroups; however, after increasing significantly from 2003—2007, the prevalence of a history of ADHD diagnosis was statistically similar between 2007 and 2011 among older teens and decreased among children who were multiracial/of other races.

Direct comparisons of the 2003 to the other medication indicators were not appropriate. From 2007—2011, medicated ADHD prevalence increased overall but remained statistically similar among children who were multiracial/of other races. Medicated ADHD estimates within each ADHD severity strata were statistically similar during this time period. The estimated treated prevalence of ADHD (mental health treatment plus medication) increased from 2007—2011, due to increases in medicated ADHD; however as many as 17.5% of children with current ADHD were not receiving one of the forms of treatment for ADHD in 2011, more than one-third of which were moderate and severe cases.

The findings in this report are subject to several limitations. First, as noted earlier, the ADHD indicators used in this report did not assess ADHD symptoms directly but rather relied on parent-report of diagnosis by a health care provider, which may introduce recall bias. The parent-reported indicators have not been clinically validated, however a recent analysis indicated that parent-reported survey data produced similar estimates as those from insurance claims data, providing evidence of convergent validity for parent-reported ADHD diagnosis by a health care provider.32 Second, the cell-phone sample inclusion could have affected the 2011 estimates; analyses of restricted-use data suggest that children living in cell-phone-only households in 2011 were more likely to have current ADHD than children living in landline households (10.0% vs. 8.4%), therefore non-coverage of cell-phone only households in 2007 may have underestimated prevalence. Third, survey responses were limited to those who agreed to participate and response rates in 2011 were lower than those in 2003 and 2007; however, nonresponse bias is attenuated by the inclusion of demographic factors in the sample weight calculations; however non-response bias cannot be ruled out. Fourth, although medication treatment and mental health treatment indicators were included in this study, other forms of treatment for ADHD were not collected and estimates of ADHD treatment may therefore underestimate treated prevalence. Finally, the cross-sectional data in this report cannot be used to determine the cause of increased prevalence or the appropriateness of diagnosis or medication treatment. However, these data do allow for ecological analyses of changes in policies and demographic characteristics, as conducted by Fulton and colleagues.33

The increasing prevalence estimates of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis are generally consistent with previous rates of increase. These increases could indicate that the actual prevalence of underlying ADHD has increased consistently over time, however the proxy data used in this report prohibits drawing firm conclusions about changes in the underlying prevalence of ADHD. The increases could also reflect better detection of underlying ADHD, due to increased health education and awareness efforts. A number of contextual factors are known to influence the frequency with which childhood ADHD is diagnosed, including increased awareness efforts, educational policies, physician characteristics, cultural factors, and changes in public perception.33–36 Other factors, such as increased confidence to treat ADHD among clinicians and increased exposure to etiologic factors (e.g., environmental contaminants) may also play a role. The magnitude of increases documented with these cross-sectional data warrant future efforts to more fully understand the factors impacting ADHD diagnosis.

The increases in parent-reported medication for ADHD is consistent with previous research28 and should be considered within a broad context. Medication treatment is the single-most effective ADHD treatment, resulting in immediate and meaningful improvements in ADHD symptoms that surpass the efficacy of behavioral therapy alone.11,12 The effectiveness of ADHD medication on ADHD symptoms has likely contributed to the ADHD medication initiation and continuance. However, we do not fully understand the long-term impact of taking ADHD medication over time. There is some evidence that long-term ADHD medication normalizes right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation.37 There is also conflicting evidence about the risk and protective effects of ADHD medication use and later substance use among adolescents and young adults.38,39 Functional outcomes are also consistently and heavily influenced by symptom trajectory, socio-demographic factors, and treatment history.40 Given the increasing medication treatment patterns and the developing literature about the risks of both intervening and failing to intervene, continued research on the long-term benefits of ADHD treatment, both pharmacological and behavioral, is needed.

Considering the overall national context, the increases in parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated medication treatment occurred during a period in which the FDA issued three Public Health Alerts and a series of communications regarding cardiac and psychiatric risks of ADHD medications.41,42 Others have documented upward trends in ADHD medication treatment despite these safety alerts, which contrast with the downward trends seen in pediatric antidepressant use following alerts regarding suicidality.41,43,44 Prevalence of ADHD medication use also increased despite an overall downward trend in pediatric medication prescriptions.45 Notably, there has been an increase in antipsychotic medication use among children, including concomitant use of multiple psychotropic medications, with the most common combination being ADHD medication and an antidepressant.46,47 Finally, the 2011 medication treatment estimates may have been somewhat constrained by the ADHD medication shortages experienced throughout the US from 2009—2011.48,49

The findings of this report have several important clinical and public health implications. Parent-reported prevalence estimates provide insight into the demand that this population has on the systems supporting them and these data suggest that the impact of ADHD may be increasing. ADHD is commonly diagnosed before age 5 in children with severe ADHD; children diagnosed with ADHD in early childhood may benefit from targeted interventions. Attention to the transitional needs of the large population of high school students taking medication for ADHD (6.4%) may be warranted, particularly given increasing concerns about abuse, misuse, and diversion of medication to others.50–52 Based on this report’s estimates, the cross-sector costs associated with ADHD likely exceed the previously estimated upper bound of $52 billion.53 Future cross-Public Health system efforts should continue to describe and monitor ADHD diagnostic and treatment patterns, assess the alignment of these patterns to best practices, and seek to understand the factors influencing the evolving prevalence of ADHD diagnosis and treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure. Percentage distribution of age of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosis by a health care provider based on retrospective parent report, by parent-reported current ADHD severity – United States, 2011

Acknowledgments

The National Survey of Children’s Health is a module of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey and was sponsored by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration. ML Danielson served as the study’s statistical expert.

Footnotes

None of the authors have any conflicts of interests to declare.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Susanna N. Visser, Division of Human Development and Disability, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, GA

Melissa L. Danielson, Division of Human Development and Disability, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, GA

Rebecca H. Bitsko, Division of Human Development and Disability, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, GA

Joseph R. Holbrook, Division of Human Development and Disability, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, GA

Michael D. Kogan, Office of Epidemiology and Research, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, in Rockville, MD

Reem M. Ghandour, Office of Epidemiology and Research, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, in Rockville, MD

Ruth Perou, Division of Human Development and Disability, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, GA

Stephen J. Blumberg, Division of Health Interview Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, in Hyattsville, MD

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV-TR. Washington, DC: APA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiScala C, Lescohier I, Barthel M, Li G. Injuries to children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1415–1421. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.6.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoare P, Beattie T. Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and attendance at hospital. Eur J Emerg Med. 2003;10:98–100. doi: 10.1097/01.mej.0000072631.17469.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merrill R, Lyon J, Baker R, Gren L. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and increased risk of injury. Adv Med Sci. 2009;54:20–26. doi: 10.2478/v10039-009-0022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Identified Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Medically Attended, Nonfatal Injuries: US School-Age Children, 1997–2002. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwebel DC, Roth DL, Elliott MN, et al. Association of externalizing behavior disorder symptoms and injury among fifth graders. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11:427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loe I, Feldman H. Academic and Educational Outcomes of Children With ADHD. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:643–654. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Katusic SK. Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults with childhood ADHD: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 2013;131:637–644. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:894–921. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318054e724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Pediatrics’ Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. ADHD: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011:128. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2654. epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD Cooperative Group. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1073–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD Cooperative Group. National Institute of Mental Health multimodal treatment study of ADHD follow-up: 24-month outcomes of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;113:754–761. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelham WE, Jr, Fabiano GA. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:184–214. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charach A, Dashti B, Carson P, et al. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Effectiveness of Treatment in At-Risk Preschoolers; Long-Term Effectiveness in All Ages; and Variability in Prevalence, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Oct, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper WO, Habel LA, Sox CM, et al. ADHD drugs and serious cardiovascular events in children and young adults. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1896–1904. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witt KL, Shelby MD, Itchon-Ramos N, et al. Methylphenidate and amphetamine do not induce cytogenetic damage in lymphocytes of children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1375–1383. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3181893620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gould MS, Walsh BT, Munfakh JL, et al. Sudden Death and Use of Stimulant Medications in Youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:992–1001. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed March 25, 2013];FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) (formerly AERS) 2013 http://go.usa.gov/2Gc4.

- 19.Getahun D, Jacobsen SJ, Fassett MJ, Chen W, Demissie K, Rhoads GG. Recent trends in childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:282–288. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garfield CF, Dorsey ER, Zhu S, et al. Trends in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder ambulatory diagnosis and medical treatment in the United States, 2000–2010. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolraich ML, McKeown RE, Visser SN, et al. The Prevalence of ADHD: Its Diagnosis and Treatment in Four School Districts Across Two States [published online ahead of print on Spetember 12, 2012] J Atten Disord. doi: 10.1177/1087054712453169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed March 6, 2012];National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm.

- 23.Blumberg SJ, Foster EB, Frasier AM, et al. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children’s Health, 2007. National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumberg SJ, Olson L, Frankel MR, Osborn L, Srinath KP, Giambo P. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children’s Health, 2003. National Center for Health Statistics; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyle CA, Boulet S, Schieve LA, et al. Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US children, 1997–2008. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1034–1042. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akinbami LJ, Liu X, Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children aged 5–17 years in the United States, 1998–2009. National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increasing prevalence of parent-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children — United States, 2003 and 2007. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1439–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuvekas SH, Vitiello B. Stimulant medication use in children: A 12-year perspective. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:160–166. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey. 2011–2012 National Survey of Children’s Health frequently asked questions. 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm.

- 30.Smith PJ, Hoaglin DC, Battaglia MP, Barker LE. Statistical methodology of the National Immunization Survey, 1994–2002. Vital Health Stat. 2005;2:1–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of diagnosis and medication treatment for ADHD - United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2005;54:842–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Perou R, Blumberg SJ. Convergent validity of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis: A cross-study comparison. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:674–675. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fulton BD, Scheffler RM, Hinshaw SP, et al. National variation of ADHD diagnostic prevalence and medication use: Health care providers and education policies. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1075–1083. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Ethnic and regional differences in primary care visits for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:318–325. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200410000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hillemeier MM, Foster EM, Heinrichs B, Heier B. Racial differences in parental reports of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder behaviors. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28:353–361. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31811ff8b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dempster R, Wildman B, Keating A. The role of stigma in parental help-seeking for child behavior problems. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42:56–67. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.700504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molina BSG, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, et al. MTA at 8 years: Prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:484–500. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819c23d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hart H, Radua J, Mataix-Cols D, Rubia K. Meta-analysis of fMRI studies of timing in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:2248–2256. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harty SC, Ivanov I, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM. The impact of conduct disorder and stimulant medication on later substance use in an ethnically diverse sample of individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21:331–339. doi: 10.1089/cap.2010.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molina BSG, Hinshaw SP, Eugene Arnold L, et al. Adolescent Substance Use in the Multimodal Treatment Study of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (MTA) as a Function of Childhood ADHD, Random Assignment to Childhood Treatments, and Subsequent Medication. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:250–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Groenman AP, Oosterlaan J, Rommelse NNJ, et al. Stimulant treatment for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and risk of developing substance use disorder. Brit J Psychiatr. 2013 doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.124784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Humphreys KL, Eng T, Lee SS. Stimulant Medication and Substance Use Outcomes: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. 2013;70:740–749. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kornfield R, Watson S, Higashi AS, et al. Effects of FDA advisories on the pharmacologic treatment of ADHD, 2004–2008. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:339–346. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed March 15, 2013, 2013];Communication about an ongoing safety review of stimulant medications used in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) 2011 http://go.usa.gov/2GcP.

- 45.Barry CL, Martin A, Busch SH. ADHD medication use following FDA risk warnings. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2012;15:119–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Du DT, Zhou EH, Goldsmith J, Nardinelli C, Hammad TA. Atomoxetine use during a period of FDA actions. Med Care. 2012;50:987–992. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31826c86f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chai G, Governale L, McMahon AW, Trinidad JP, Staffa J, Murphy D. Trends of Outpatient Prescription Drug Utilization in US Children, 2002–2010. Pediatrics. 2012;130:23–31. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Comer JS, Olfson M, Mojtabai R. National trends in child and adolescent psychotropic polypharmacy in office-based practice, 1996–2007. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C, Gerhard T. Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:13–23. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris GFD. A finds short supply of attention deficit drugs. New York Times. 2012 Jan 1; [Google Scholar]

- 51.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed March 25, 2013];FDA works to lessen drug shortage impact. 2011 http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm258152.htm.

- 52.Graf WD, Nagel SK, Epstein LG, Miller G, Nass R, Larriviere D. Pediatric neuroenhancement: Ethical, legal, social, and neurodevelopmental implications. Neurology. 2013;80:1251–1260. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318289703b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The DAWN report: emergency department visits involving attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder stimulant medications. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; Jan 24, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Drug Enforcement Administration. Prescription for disaster: how teens abuse medicine. Drug Enforcement Administration; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pelham WE, Foster EM, Robb JA. The economic impact of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in children and adolescents. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure. Percentage distribution of age of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosis by a health care provider based on retrospective parent report, by parent-reported current ADHD severity – United States, 2011