Abstract

Introduction

Up to 15% of patients with cardiothoracic trauma require emergency surgery, and death can be prevented in a substantial proportion of this group. UK reports have emphasised the need for improvement in this field. We assessed major cardiothoracic trauma (MCT) outcomes in North West England over 11 years.

Methods

The database from the Trauma Audit and Research Network was used to retrieve data for all patients who had suffered MCT between 2000 and 2011 in North West England and the findings analysed. Trauma that led to thoracotomy/thoracoscopy or sternotomy was defined as MCT.

Results

A total of 146 patients were identified, and a considerable male predominance (88.4%) noted. A total of 54.1% had sustained penetrating cardiothoracic trauma. Also, 53.4% had been admitted to tertiary-care hospitals for trauma (TCHT) and 46.6% had been admitted to non-TCHT. Overall prevalence of mortality was 35.6%. No significant difference was found in mortality between TCHT vs non-TCHT. Prevalence of mortality was significantly higher in the subgroup of patients cared for exclusively in non-TCHT compared with patients transferred from non-TCHT to TCHT (41% vs 13.8%, p<0.05).

Conclusions

No significant difference was demonstrated in length of stay in hospital/length of stay in the intensive treatment unit and prevalence of mortality between patients originally presenting in TCHT and those presenting in non-TCHT. However, patients transferred from non-TCHT to TCHT had a lower prevalence of mortality. These findings may constitute a valuable benchmark for comparison with results arising after introduction of trauma centres in the UK.

Keywords: Trauma (blunt/penetrating), chest, emergency, thoracotomy, sternotomy, VATS, outcomes, trauma centre

Trauma remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide. 1,2 Approximately 20% of all trauma patients sustain cardiothoracic injuries. 3 Up to 15% of such patients will require emergency life-saving surgery, and death can be prevented in a significant proportion of these individuals. 4,5 In 2007, a UK National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) report highlighted that as much as 60% of trauma patients may have received a standard of care that was inferior to that considered to be ‘good practice’. 6 Furthermore, Smith et al. 7 reported suboptimal management of multi-trauma patients in several UK hospitals, especially with regard to thoracic trauma.

A recent initiative by National Health Service North West aims to develop a regional trauma network by centralising trauma services to tertiary-care hospitals for trauma (TCHT), which are referred to as ‘major trauma centres’. 8 This network is led by collaborations between major trauma centres in Manchester and Liverpool as well as Royal Preston Hospital. The hope is that this network will lead to improved outcomes. The ultimate goal is to address the challenges mentioned above by directing the care of critically injured patients to centres who care for a greater number of patients and who have greater experience and resources.

We retrospectively assessed the outcomes of patients with major cardiothoracic trauma (MCT) in North West England between 2000 and 2011 before institution of the North West Trauma Network.

Methods

Data for all adult patients admitted to hospitals in North West England due to MCT between January 2000 and January 2011 were retrieved from the Trauma, Audit and Research Network (TARN) 9 database. TARN was instituted in the late-1980s and is responsible for the collection of data on trauma at a national level, with an aim to aid research and improve outcomes in this field. MCT was defined as trauma in which cardiothoracic intervention(s) more invasive than tube thoracostomy had been undertaken (ie thoracotomy, median sternotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery). 10 The geographic area covered entailed Greater Manchester, Cumbria & Lancashire, and Merseyside & Cheshire, which has a cumulative population of ≈6.9 million. 11 Hospitals were classified as ‘TCHT’ and ‘non-TCHT’ because the study period predated institution of UK trauma centres.

Twenty-one regional hospitals that received adult patients with major trauma during the study period were identified: 6 were TCHT and 15 were non-TCHT. For each patient included in the study, data on the following parameters were collected: year of the incident; admitting hospital; age; sex, clinical parameters upon arrival to the emergency department (heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure (SBP), oxygen saturation); mechanism of injury (blunt vs penetrating); major cardiothoracic injury and other major concurrent injuries; surgical interventions; location of initial assessment/management (TCHT vs non-TCHT); inter-hospital transfer; length of stay in hospital (LOS); length of stay in the intensive treatment unit (ITU LOS); and final outcome. If required, clinical information, operation notes, and imaging reports were reviewed to crosscheck for miscoding and to obtain missing information. Injury severity was determined using the Abbreviated Injury Scale score and Injury Severity Score (ISS). 7

Statistical analyses

Data for continuous variables are given as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Comparisons between groups were undertaken using the Mann–Whitney U-test and X 2 test, as appropriate. All tests were based on a two-sided α-value of 0.05. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS v19 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Demographics

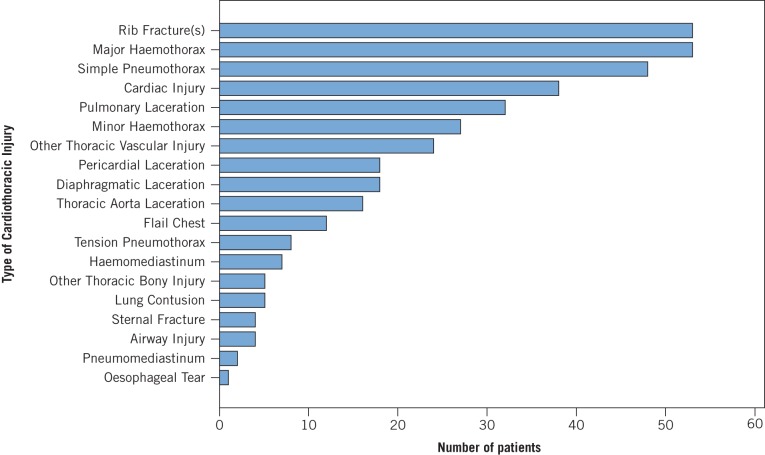

Of 28,052 trauma patients admitted to hospitals in North West England over the 11-year study period, 226 subjects with MCT were identified from the TARN database. This initial cohort was subjected to further review to identify patients who did not satisfy the inclusion criteria, which resulted in the exclusion of 80 miscoded patients. Ultimately, 146 patients (129 males (88.4%) and 17 females (11.6%)) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the analyses. Median age for the entire cohort was 31.5 (IQR: 23.1–44.5) years. Median ISS was 25 (IQR: 14–34), with males having high ISS scales (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of patients per Injury Severity Scale (ISS) score (Sorted by 5 ISS units) distributed according by gender

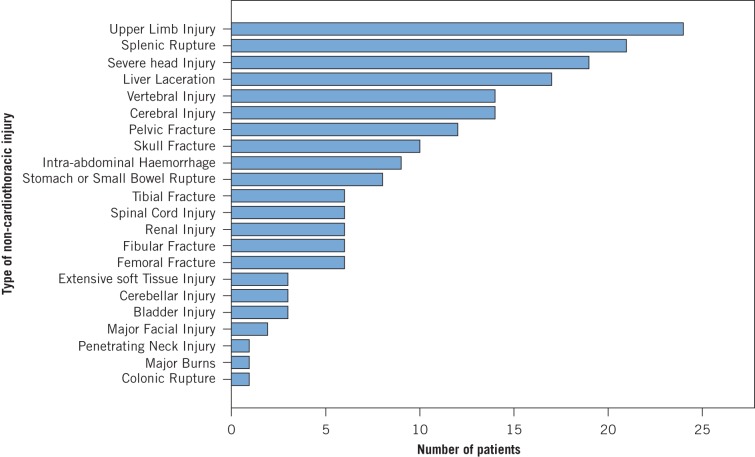

Sixty-eight patients (46.6%) presented in TCHT, whereas 78 (53.4%) presented in non-TCHT. Penetrating trauma was observed in 79 subjects (54.1%), whereas 67 patients (45.9%) sustained blunt trauma (Figure 2). The latter were associated with higher ISS (p<0.05). This observation could be due to the higher prevalence of head injuries in this group (30.9%) compared with the penetrating-trauma group (2.6%) (p<0.05). Demographics and patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Number of patients according to mechanism of injury (error bars: 95% confidence interval).

Table 1.

Cross-tabulation of demographics and patient characteristics. Figures in brackets represent column percentages unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Overall sample | TCHT presentation | Non-TCHT presentation | Penetrating subgroup | Blunt subgroup | Survivors | Non-Survivors |

| ISS, Injury Severity Score; TCHT: Tertiary care hospital for trauma; Non-TCHT: Non-tertiary care hospital for trauma; LOS: Length of stay (days); ITU: Intensive treatment unit; IQR: Interquartile range. | |||||||

| aRange | |||||||

| Ratio (%) | Ratio (%) | Ratio (%) | Ratio (%) | Ratio (%) | Ratio (%) | Ratio (%) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 129/146 (88.4) | 59/68 (86.8) | 70/78 (89.7) | 69/79 (87.3) | 60/67 (89.6) | 81/94 (86.2) | 48/52 (92.3) |

| Female | 17/146 (11.6) | 9/68 (13.2) | 8/78 (10.3) | 10/79 (12.7) | 7/67 (10.4) | 13/94 (13.8) | 4/52 (7.7) |

| Presentation to TCHT | |||||||

| Yes | 68/146 (46.6) | n/a | n/a | 34/79 (43.0) | 34/67 (50.7) | 43/94 (45.7) | 25/52 (48.1) |

| No | 78/146 (53.4) | n/a | n/a | 45/79 (57.0) | 33/67 (49.3) | 51/94 (54.3) | 27/52 (51.9) |

| Mechanism of Injury | |||||||

| Blunt | 67/146 (45.9) | 34/68 (50.0) | 33/78 (42.3) | n/a | n/a | 36/94 (38.3) | 31/52 (59.6) |

| Penetrating | 79/146 (54.1) | 34/68 (50.0) | 45/78 (57.7) | n/a | n/a | 58/94 (61.7) | 21/52 (40.4) |

| Mortality | |||||||

| Yes | 52/146 (35.6) | 25/68 (36.8) | 27/78 (34.6) | 21/79 (26.6) | 31/67 (46.3) | n/a | n/a |

| No | 94/146 (64.4) | 43/68 (63.2) | 51/78 (65.4) | 58/79 (73.4) | 36/67 (53.7) | n/a | n/a |

| Laparotomy | |||||||

| Yes | 41/146 (28.1) | 16/68 (23.5) | 25/78 (32.1) | 18/79 (22.8) | 23/67 (34.3) | 22/94 (23.4) | 19/52 (36.5) |

| No | 105/146 (71.9) | 52/68 (76.5) | 53/78 (67.9) | 61/79 (77.2) | 44/67 (65.7) | 72/94 (76.6) | 33/52 (63.5) |

| Median age (IQR) | 31.5 (23.1–44.5) | 29.1 (22.2–44.3) | 32.6 (25.1–44.9) | 28.2 (22.5–38.0) | 37.2 (25.4–51.8) | 32.6 (23.9–44.1) | 30.2 (22.6–45.5) |

| Median ISS (IQR) | 25 (14–34) | 25 (16–34) | 25 (13–34) | 18 (10–25) | 29 (19–41) | 18 (10–27) | 28 (25–42) |

| Median LOS (IQR) | 6 (1–12) | 7 (1–12) | 6 (1–12) | 7 (1–10) | 6 (1–17) | 9 (6–21) | 1 (1–10)a |

| Median ITU LOS (IQR) | 0 (0–5) | 1 (0–5) | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–7) | 3 (0–7) | 0 (0–9)a |

Cardiothoracic injuries

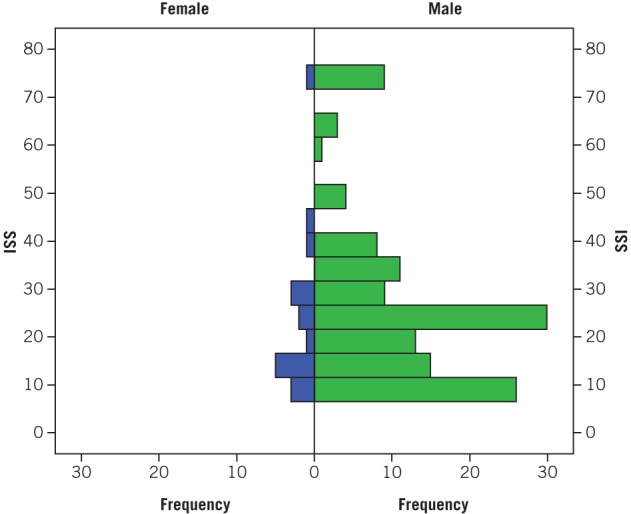

The most commonly encountered thoracic injuries were rib fractures (36.3% of patients) and major haemothorax (36.3%), followed by simple pneumothorax (32.9%) and pulmonary lacerations (21.2%). Cardiac injuries were present in 38 patients (26%), with 11.6% of patients sustaining pericardial laceration, 6.1% having a laceration to a coronary artery, 3.4% suffering cardiac tamponade, and 1.4% sustaining simple haemopericardium without tamponade. The prevalence of each type of cardiothoracic injury is summarised in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Breakdown of cardiothoracic injuries

Associated non-cardiothoracic injuries

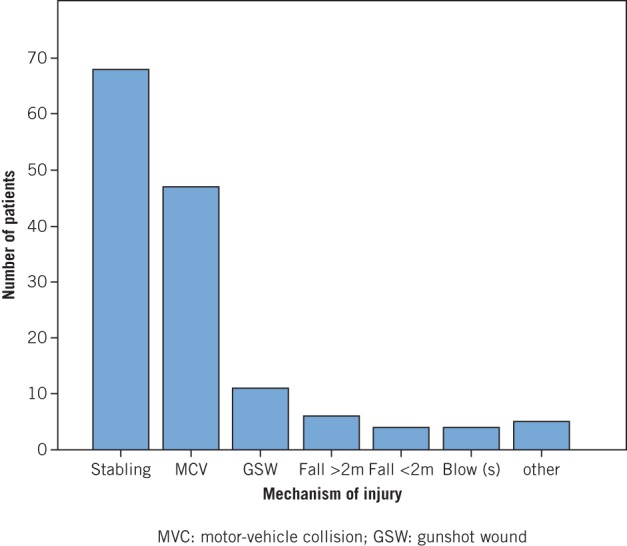

Severe injury to the head was observed in 19 patients (13%), and all were classified as AISHead ≥3. Such injuries were more frequent after blunt trauma and were associated with a mortality of 62%, with 25% of all head-injured patients requiring craniotomy. Furthermore, 6 patients suffered injury to the spinal cord (4.1%), the severity of which ranged from contusion of the spinal cord to complete spinal cord syndrome (AISSpine, 2–6), and with an overall mortality of 67%. Abdominal injury was encountered in 33% of all the patients, and management ranged from simple observation to immediate life-saving laparotomy. Splenic rupture was the most common form of intra-abdominal injury, and occurred in 21 patients (14.4%; AISAbdomen, 2–5). A summary of the prevalence of all major non-cardiothoracic injuries encountered is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of non-cardiothoracic injuries

Mortality

Overall in-hospital mortality was 35.6% (52 of 146 patients). In contrast with previous reports, 12,13 a significant difference in in-hospital mortality was demonstrated between patients treated in TCHT and those treated in non-TCHT (36.8% vs 34.6%). Males had a higher prevalence of mortality than females (37.2% vs 23.5%), a difference that did not reach significance. Motor-vehicle collisions (MVCs) were associated with the highest in-hospital mortality (53.2%), followed by gunshot injuries (45.5%) and stabbing (23.5%) (p=0.014). The vast majority of deaths occurred early, regardless of the ISS of individual patients. Specifically, 43 of 52 deaths occurred on the day of hospital admission (82.7%), and no in-hospital deaths occurred after day-10. Patients who sustained concurrent severe trauma to the head had a prevalence of mortality of 63.2%, in comparison with 31.5% for patients who did not sustain such an injury (p=0.015). Importantly, the prevalence of mortality for patients who suffered blunt trauma was significantly higher than that for patients who sustained penetrating trauma (46.3% vs 26.6%, p=0.021).

LOS and ITU LOS

Median LOS for the entire patient cohort was 6 (IQR: 1–12) days. Sixty-nine patients (47.3%) were admitted to the ITU, with a median ITU LOS of 5 (IQR: 3–10) days. Male patients had a significantly longer LOS (p=0.041), but not ITU LOS (p=0.324) in comparison with female patients. A higher (but not significant) LOS and ITU LOS was demonstrated for patients who sustained falls from a height >2 m and MVC. No significant difference in LOS and ITU LOS between patients who suffered blunt trauma and those who sustained penetrating trauma was discovered. Interestingly, against expectations and overwhelming evidence in the literature, a significant difference in LOS and ITU LOS between TCHT and non-TCHT was not revealed.

The effect of severe injury to the head upon LOS and ITU LOS was also investigated because it constitutes one of the major determinants of outcome in trauma patients. 17 Patients who suffered from severe injuries to the head had a significantly shorter LOS (p=0.018), but a longer ITU LOS that did not reach significance (p=0.603). This observation could be attributed to the increased clinical requirements of this patient group upon presentation (longer ITU LOS), followed by early deaths.

Clinical observations

In general, patients who died had lower SBP, lower oxygen saturation, higher respiratory rate, and a faster heart rate. However, a significant difference was not shown for any of these variables. Only SBP approached significance (p=0.076).

Transfers

In this cohort, 29 patients (19.9%) required transfer from the initial receiving hospital to TCHT or from units without a cardiothoracic service to others with a cardiothoracic service for definitive management. Prevalence of mortality for this subgroup of patients was 13.8% and was significantly lower that for patients who had not been transferred (41%, p<0.05), whereas both groups had a median ISS of 25.

Discussion

The concept of managing major trauma at designated trauma centres as well as institution of trauma systems are relatively novel in the UK. Increase in awareness of this concept took place after a joint report by the Royal College of Surgeons of England and the British Orthopaedic Association in 2000. 3 However, management of major trauma remains a significant challenge. Up to 20% of subjects who have suffered major trauma admitted to UK hospitals have sustained significant cardiothoracic injuries. 14 Also, a substantial proportion of such subjects have been ‘under-managed’ or have not received optimal care, according to recent reports. 7,15 The low prevalence of major trauma in civilians and the consequent lack of experience are considered to be the main causes of inferior outcomes of victims of major trauma in the UK in comparison with other countries, 6,14,16 an observation that has motivated this reform.

Designation of trauma centres has been shown to significantly improve the care of critically ill trauma patients in the USA, 12,17 especially with regard to severe injuries to vital organs (eg cardiovascular, 18 brain 19 ). This phenomenon has been related directly to the experience gained by such centres due to the higher volume of patients they receive, 6,16,18,20 a fact that has led to reductions in mortality of as much as 50%. 20 According to Smith et al. 21 mortality in each hospital is inversely proportional to the volume of trauma patients cared for. This claim has also been supported by a study by Nathens et al. 20 that demonstrated a significantly shorter LOS for patients admitted to major trauma centres in comparison with other hospitals. Conversely, in a retrospective study by Demetriades et al., 18 case volume was not associated with outcome, but significantly better outcomes were demonstrated in major trauma centres in comparison with other hospitals (25.3% vs 29.3%).

The role of pre-hospital care teams and ambulance services is undoubtedly crucial in the function of a trauma system. 22 However, the present study was not designed to assess this parameter. A report from NCEPOD 6 advised a minimal delay in patient transfer. Hence, the role of ‘in-the-field’ interventions for critically injured subjects has been reviewed to shift the focus on timely transfer to definitive care. According to TARN data, transfer times in the UK are significantly prolonged due to the on-site assessment and intervention of patients. 22

Data from the present study date to before the formal designation of trauma centres. However, it is considered that major tertiary academic hospitals (designated as ‘major trauma centres’ from April 2012) had superior expertise, resources, volume of admissions of trauma patients, and availability of services compared with smaller urban and district general hospitals (termed’ trauma units’ from April 2012). Therefore, comparison of outcomes between major hospitals and smaller, acute hospitals in the present study can be considered valid.

Penetrating injuries were more common than blunt injuries in the present study, in contradiction with findings from UK studies on general trauma. 23 Stabbing injuries were the most common mode of injury, followed by MVC. The vast majority of patients were male, and males had a longer LOS, a finding that was in accordance with other studies. 19,20 Importantly, neurological trauma in the context of blunt MCT has been shown to lead to significantly worse outcomes, 24 a finding that was supported by the present study. This catastrophic feature of cardiothoracic trauma further supports institution of trauma systems in which availability of expertise and facilities would allow for prompt management of multiple trauma.

A significant difference in the prevalence of mortality between TCHT and non-TCHT was not revealed by the present study, a finding that could be attributed to the small sample size. These findings may provide further support to the requirement for institution of ‘trauma networks’ as opposed to trauma centres per se, as eluded by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma in 2006. 25 It has been estimated that 450–600 lives per year could be saved across England and Wales thanks to institution of UK trauma systems. 26 However, it is perhaps too early to conclude whether national outcomes will improve in the long term. Findings of the present study may serve as a valuable benchmark for comparison with results arising after introduction of trauma systems in the UK.

Conclusions

No significant difference was demonstrated between LOS/ITU LOS and mortality between patients originally presenting in TCHT and non-TCHT before introduction of trauma systems in the UK. However, patients transferred from non-TCHT to TCHT had a lower prevalence of mortality. Blunt MCT was strongly associated with multiple-organ injury (multiple intra-thoracic and/or concurrent severe head injuries and intra-abdominal injuries) and a high ISS score. This finding highlighted the importance of prompt admission/transfer of such patients to major trauma centres, where the appropriate resources and expertise are available. Further studies focusing on outcomes after introduction of UK trauma systems and designation of trauma centres will be necessary to provide more contemporary data.

Acknowledgements

This study was undertaken as part of MSc in surgical sciences of the Edinburgh Surgical Sciences Qualification (ESSQ) offered by the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and the Edinburgh University.

Support from Mrs Antoinette Edwards (Project and Research Manager, TARN), Professor Fiona Lecky (Research Director, TARN), Mr Tom Lawrence (System analyst, TARN), Mr. Omar Bouamra (Medical Statistician, TARN) and Ms. Dena Khorsandi (statistics advice, McGill university, Montreal, Canada) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1. Spahn DR, Coats CV, Duranteau J, et al. Management of bleeding following major trauma: a European guideline. Crit Care 2011; 11: R17 [Erratum in Crit Care 2007; 11: 414]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krug EG, Sharma GK, Lozano R. The global burden of injuries. Am J Public Health 2000; 90: 523–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Royal College of Surgeons of England and the British Orthopaedic Association. Better care for the severely injured London: RCSE/BOA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hunt PA, Greaves I, Owens WA. Emergency thoracotomy in thoracic trauma – a review. Injury 2006; 37: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moloney JT, Fowler SJ, Chang W. Anesthetic management of thoracic trauma. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2008;21: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Trauma: who cares? London: NCEPOD, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith N, Weyman D, Findlay G et al. The management of trauma victims in England and Wales: a study by the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg 2009; 36: 340–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheshire M. Progress on major trauma transformation NHS North West, 2011. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Trauma Audit and Research Network. www.tarn.ac.uk. Viewed 3/3/2014.

- 10. Rachid MA. Cardiothoracic trauma: a Scandinavian perspective. Doctoral thesis. Göteborg: Göteborg University, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Young R, Sly F. Portrait of the North West. London: Office for National Statistics 2011; 43. [Google Scholar]

- 12. MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. New Engl J Med 2006; 354: 366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Demetriades D, Martin M, Salim A et al. Relationship between American College of Surgeons trauma center designation and mortality in patients with severe trauma (injury severity score >15). J Am Coll Surg 2006; 202: 212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brohi K PT, Coats T. Regional trauma systems: interim guidance for commissioners London: Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anderson ID, Woodford M, de Dombal FT, Irving M. Retrospective study of 1000 deaths from injury in England and Wales. Br Med J (clinical research edition) 1988; 296: 1,305–1,308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brooks A, Butcher W, Walsh M, Lambert A, Browne J, Ryan J. The experience and training of British general surgeons in trauma surgery for the abdomen, thorax and major vessels. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2002; 84: 409–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Demetriades D, Martin M, Salim A et al. Relationship between American College of Surgeons trauma center designation and mortality in patients with severe trauma (injury severity score >15). J Am Coll Surg 2006; 202: 212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Demetriades D, Martin M, Salim A, Rhee P, Brown C, Chan L. The effect of trauma center designation and trauma volume on outcome in specific severe injuries. Ann Surg 2005; 242: 512–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. DuBose JJ, Browder T, Inaba K, Teixeira PG, Chan LS, Demetriades D. Effect of trauma center designation on outcome in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Arch Surg 2008; 143: 1213–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Maier RV et al. Relationship between trauma center volume and outcomes. JAMA 2001; 285: 1,164–1,171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith RF, Frateschi L, Sloan EP et al. The impact of volume on outcome in seriously injured trauma patients: two years' experience of the Chicago Trauma System. J Trauma 1990; 30: 1,066–1,075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ambulance Service Network NHS Confederation. Implementing trauma systems: key issues for the NHS London: NHS Confederation, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Veysi VT, Nikolaou VS, Paliobeis C, Efstathopoulos N, Giannoudis PV. Prevalence of chest trauma, associated injuries and mortality: a level I trauma center experience. Int Orthop 2009; 33: 1,425–1,433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khorsandi M, Skouras C, Shah R. Is there any role for resuscitative emergency department thoracotomy in blunt trauma? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012; 16: 509–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Resources for optimal care of the injured patient. Washington DC; National Academies Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26. NHS England. Major trauma services 2012. www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/AboutNHSservices/Emergencyandurgentcareservices/Pages/Majortraumaservices.aspx Cited 8/2/2015.