Abstract

Adult ingestion of caustic substances is an unusual but serious surgical problem, with injuries likely to be more extensive than those in the corresponding paediatric population. After initial stabilisation and airway management, clinicians are presented with a complex multisystemic problem, frequently requiring a multidisciplinary approach involving several surgical disciplines and associated therapies. A new multidisciplinary team was convened to discuss complex ingestion injury in adults and established techniques were used to bring forward a proposed treatment algorithm. An algorithm may potentially improve clinical efficacy and risk in the management of these complex patients.

Keywords: Caustics, Self-injurious behaviour, Injury, Deglutition disorders, Laryngostenosis

Ingestion of caustic substances is an unusual but potentially serious problem. Incidence varies with nation and culture; example figures include between 5,000 and 15,000 ingestion injuries annually in the US. 1 Retrospective studies have found that overall morbidity and mortality is lower in children, probably owing to the fact that they are more likely to ingest harmful substances accidentally as opposed to attempting suicide, 2–4 although a study of 124 adult cases over 10 years found that 82% involved accidental ingestion and only 18% were suicide attempts. 5

Approximately 1–2% of cases in all age groups result in stricture formation 1 and 10% of cases in adults result in death. 6 Age over 60 years has been found to be a risk factor for death, 6 which generally results from metabolic effects. 7 Severity of initial injury 8,9 and age over 65 years 9 have been found to be predictors of morbidity in the long term although it has also been reported that while degree of co-morbidity correlates with mortality, severity of injury does not. 9

Pathophysiology varies between injury due to acid and alkaline substances. Acid causes coagulation necrosis, resulting in denaturation of the superficial protein layer and eschar formation. This protects against further damage but is replaced by granulation tissue as it matures, potentially causing obstruction of luminal structures, and increasing the risk of perforation and haemorrhage. 1,10–12

Alkaline substances cause tissue injury by liquefactive necrosis, involving solubilisation of proteins, saponification of fats and eventual cell death. 1,10,12 There is a substantial risk of tissue injury within minutes of alkaline contact and alkali ingestion can therefore threaten the airway within a short time. Initial tissue swelling may persist for up to 48 hours, after which necrotic tissue is replaced by granulation tissue. Prolonged contact increases the depth of the injury, also increasing the likelihood of subsequent stricture formation. 11

Initial management is directed towards stabilisation of the patient’s acute problems. An early definitive airway is advisable, with a low threshold for emergency tracheostomy if airway instrumentation proves challenging. Vomiting and haematemesis can complicate the initial management and there is a risk of severe acid–base imbalance. 1,12,13 It is advisable to avoid blind placement of nasogastric or orogastric tubes until the extent of the injury is known and for this reason, emergent gastric lavage is also not generally recommended. 14

Multidisciplinary management is recommended in all cases. 15 Early endoscopic examination in both adults and children is advocated by several authors, 4,16–19 particularly since injures in the stomach and duodenum can be masked by those in the oesophagus. 20 Some authors have recommended avoidance of diagnostic endoscopy between 5 and 15 days following injury as tissues are thought to be most friable during this period. 11 Cross-sectional imaging has also been found to be useful. 21

Surgical intervention has been reported to give an acceptable level of function 22 although the need for emergent surgical intervention has been correlated with poorer long-term outcome. 23,24 Treatment with systemic steroids has been advocated in children to decrease the likelihood of severe stricture formation. 25

Algorithms and guidelines have been in regular use in medical and surgical practice for many years. They are used principally alongside formal surgical education to guide clinicians in unusual, challenging or emergency situations, with the aim of increasing clinical efficacy and reducing inherent cost and risk. 26,27 Authors of one paper concerning experience with caustic ingestion injuries commented that there is currently no accepted protocol for their management. 28

Methods

Two of the authors (MB and GS) have research interests in airway reconstruction and advise established multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) for complex airway disease. Early in 2013, five referrals (three international, two domestic) were received by the Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital and University College Hospital (both in London, UK), detailing patients with complex upper aerodigestive ingestion injury. It was decided that a new MDT should be convened to pool the best available expertise across surgical disciplines. All authors were members of the MDT. One case could not be presented owing to lack of detail so four cases were discussed at the first meeting. One concerned a child and the remaining three are outlined below.

During the multidisciplinary review of cases, the Interacting Group Method 29 was used to arrive at a first draft of algorithmic guidelines. This method is analogous to a standard roundtable discussion of a problem (albeit with an emphasis placed on open discussion of ideas and honesty of feedback). The endpoint of the discussion is consensus. The Delphi technique 29,30 grew out of the observation that when such consensus is sought, the decision of a roundtable discussion group can show a bias towards intervention and risk.

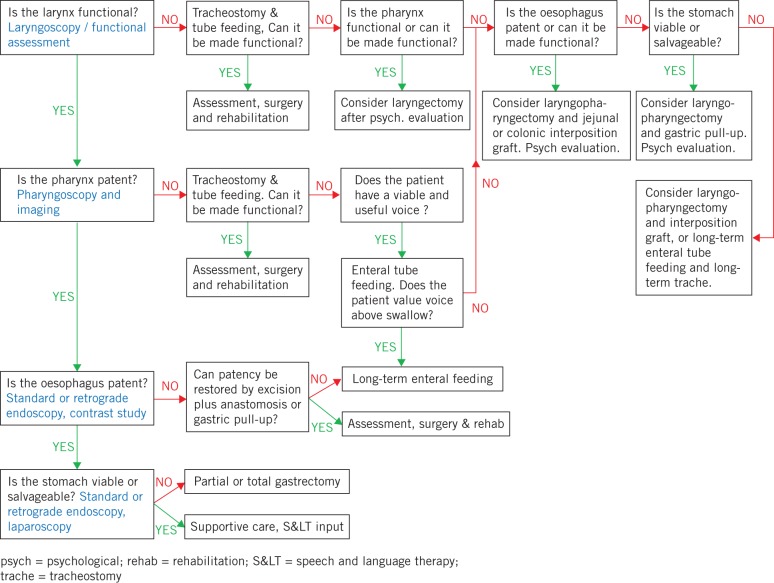

The Delphi method was conceived as a technique for arriving at a consensus judgement; it attempts to overcome the weaknesses of a traditional roundtable discussion format by allowing greater time for reflection and individual objectivity, by conducting discussions at a distance and through a moderator, who enforces a degree of isolation between the participants and anonymises feedback. In this instance, a modified Delphi technique was conducted via email with the members of the MDT to modify, refine and finalise the algorithm (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

The proposed algorithm resulting from the Delphi process

Case 1

An adult female ingested 96% sulphuric acid during a suicide attempt. After stabilisation, initial investigations revealed that the stomach was unsalvageable. A gastrectomy was therefore performed and a feeding jejunostomy inserted. She developed complete oesophageal luminal closure from severe stricturing and full-thickness pharyngeal burns with a severely narrowed pharyngeal lumen. The larynx was non-functional and imaging revealed evidence of pulmonary aspiration. The MDT elected to offer a laryngopharyngectomy and colonic interposition grafting subject to satisfactory psychological evaluation.

Case 2

An adult female, referred from overseas, forcibly ingested alkaline during an assault. After stabilisation, initial investigations revealed complete oesophageal closure and a feeding jejunostomy was inserted. The patient breathes nasally but voice and aspiration status is currently unknown. The MDT recommended functional evaluation of the larynx and laparoscopic evaluation of the stomach, proceeding to a standard oesophagectomy and gastric pull-up if feasible. Colonic interposition grafting might provide an alternative route if the stomach were found to be unsalvageable.

Case 3

An adult female ingested 500ml of household bleach during a suicide attempt. A tracheostomy was placed during initial stabilisation and a feeding jejunostomy was placed shortly thereafter. Examination revealed the supraglottic structures to be replaced by a complete ring of scar tissue. The vocal folds were structurally spared but laryngeal sensation and vocal function were poor. She underwent treatment with botulinum toxin to reduce secretion of saliva. The MDT recommended retrograde endoscopy to assess the lower oesophagus but believed that reconstructive surgery of the pharynx and larynx would be unlikely to succeed in improving function. The larynx could therefore not be considered a viable organ, and (dependent on further oesophageal findings and psychological evaluation) the best chance of improved quality of life would be through a laryngopharyngectomy, jejunal interposition graft and surgical voice restoration.

Results

The proposed algorithm represents the outcome of the MDT’s discussions. The algorithm is structured as a binary logical cascade, consisting of a tree of questions with ‘yes/no’ answers, mirroring the deductive reasoning employed by the MDT.

Consultation of the algorithm should begin in the top left corner and follow a path by answering the cascade of ‘yes/no’ questions until a treatment recommendation is reached. Grey text advises investigation modalities, which those using the algorithm may choose to employ.

At several points in the algorithm, the user is asked to consider whether a particular organ can be made functional or whether it is thought unsalvageable. This may well require the opinion of various specialists including surgeons and therapists, and it is anticipated that the algorithm will be most useful once all such opinions have been sought. Many treatment recommendations advise initial psychological evaluation since the psychological impact of these injuries and their (possibly extensive and invasive) treatment should not be underestimated.

For Patient 2, the MDT was asked to review documents, clinical imaging and data without any member of the MDT being able to examine the patient directly. In this case, the algorithm pointed to two potential outcomes, based on the findings of a single investigation. Psychological preparation for these outcomes could therefore begin locally while an offer to transfer, investigate and treat the patient was being prepared.

Discussion

Although unusual, ingestion of a caustic substance can be a serious surgical problem, spanning several surgical disciplines and requiring a multidisciplinary collaborative approach in the event of serious injury and stricture formation. Algorithms are used widely in the management of serious injury owing to their tendency towards risk reduction and clinical efficacy, and their use has been encouraged in a range of medical emergency situations in recent years (including widespread use in cardiac, paediatric and trauma life support). They may be particularly useful in unusual or rare situations, in which even experienced surgeons may not have been called on often to make critical management decisions before.

It seems logical that patients with serious upper aerodigestive and upper gastrointestinal injuries should be managed in a centre offering appropriate clinical expertise in the fields of upper gastrointestinal surgery, otolaryngology and reconstructive surgery as well as psychological and therapeutic support. In the majority of cases, this is most likely to be a large university associated hospital.

The above algorithm represents the result of our MDT’s discussions and the Delphi process, both in terms of surgical principles and with specific reference to the above described cases and others. The key questions in this algorithm mirror the approach taken by the MDT and centre on whether affected organs can be made functional with surgical or therapeutic interventions, or, conversely, whether they are felt to be unsalvageable.

During the Delphi process, the MDT gave careful consideration to the order in which such questions might arise, given the need to assess security of an affected patient’s airway, nutrition, enteral feeding, swallowing and voice. We believe that the resulting approach deals first with the most serious threats to life, before moving on to important quality of life issues subsequently. Following one particular path through the algorithm, it is necessary to consider whether a patient values voice above swallowing as this will determine whether long-term tube feeding is recommended over laryngopharyngectomy. Naturally, this is a decision that only the patient can make, and it is anticipated that he or she would require a good deal of support and understanding to do so.

Conclusions

There is no algorithm currently in existence in the literature suggesting a management schema for caustic ingestion injury of the upper aerodigestive tract. In light of this, we propose that such an algorithm may potentially bring benefit in terms of clarity, clinical efficacy, cost and risk reduction.

References

- 1. Schaffer SB, Hebert AF. Caustic ingestion. J La State Med Soc 2000; 152: 590–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ofri A, Harvey JG, Holland AJ. Pediatric upper aero-digestive and respiratory tract burns. Int J Burns Trauma 2013; 3: 209–213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adedeji TO, Tobih JE, Olaosun AO, Sogebi OA. Corrosive oesophageal injuries: a preventable menace. Pan Afr Med J 2013; 15: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kay M, Wyllie R. Caustic ingestions in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2009; 21: 651–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Celik B, Nadir A, Sahin E, Kaptanoglu M. Is esophagoscopy necessary for corrosive ingestion in adults? Dis Esophagus 2009; 22: 638–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lu LS, Tai WC, Hu ML et al. Predicting the progress of caustic injury to complicated gastric outlet obstruction and esophageal stricture, using modified endoscopic mucosal injury grading scale. Biomed Res Int 2014; 919870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. Aquila I, Pepe F, Di Nunzio C et al. Suicide case due to phosphoric acid ingestion: case report and review of literature. J Forensic Sci 2014; 59: 1,665–1,667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elshabrawi M, A-Kader HH. Caustic ingestion in children. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 5: 637–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang JM, Liu NJ, Pai BC et al. The role of age in predicting the outcome of caustic ingestion in adults: a retrospective analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 2011; 11: 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Browne J, Thompson J. Caustic Ingestion In: Cummings CW, Flint PW, Haughey BH et al. Cummings Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery. 4th edn. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2005. pp4,330–4,341. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weigert E, Black A. Caustic ingestion in children. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2005; 5: 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Espinola TE, Amedee RG. Caustic ingestion and esophageal injury. J La State Med Soc 1993; 145: 121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Browne J, Thompson J. Caustic Ingestion In: Bluestone CD, Stool SE, Alper CM et al. Pediatric Otolaryngology. 4th edn.Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003. pp4,330–4,342. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lamireau T, Rebouissoux L, Denis D et al. Accidental caustic ingestion in children: is endoscopy always mandatory? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001; 33: 81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dray X, Cattan P. Foreign bodies and caustic lesions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013; 27: 679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boskovic A, Stankovic I. Predictability of gastroesophageal caustic injury from clinical findings: is endoscopy mandatory in children? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 26: 499–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Temiz A, Oguzkurt P, Ezer SS et al. Predictability of outcome of caustic ingestion by esophagogastroduodenoscopy in children. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18: 1,098–1,103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cabral C, Chirica M, de Chaisemartin C et al. Caustic injuries of the upper digestive tract: a population observational study. Surg Endosc 2012; 26: 214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheng HT, Cheng CL, Lin CH et al. Caustic ingestion in adults: the role of endoscopic classification in predicting outcome. BMC Gastroenterol 2008; 8: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ananthakrishnan N, Parthasarathy G, Kate V. Acute corrosive injuries of the stomach: a single unit experience of thirty years. ISRN Gastroenterol 2011; 914013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21. Lurie Y, Slotky M, Fischer D et al. The role of chest and abdominal computed tomography in assessing the severity of acute corrosive ingestion. Clin Toxicol 2013; 51: 834–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Javed A, Pal S, Krishnan EK et al. Surgical management and outcomes of severe gastrointestinal injuries due to corrosive ingestion. World J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 4: 121–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Contini S, Scarpignato C. Caustic injury of the upper gastrointestinal tract: a comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19: 3,918–3,930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chirica M, Resche-Rigon M, Bongrand NM et al. Surgery for caustic injuries of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Ann Surg 2012; 256: 994–1,001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Usta M, Erkan T, Cokugras FC et al. High doses of methylprednisolone in the management of caustic esophageal burns. Pediatrics 2014; 133: E1518–E1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wood MD, Bostrom A, Bridges T, Linkov I. Cognitive mapping tools: review and risk management needs. Risk Anal 2012; 32: 1,333–1,348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bozzetti F. Surgical guidelines: more useful to physicians than to patients. Gastric Cancer 2004; 7: 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robustelli U, Bellotti R, Scardi F et al. Management of corrosive injuries of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Our experience in 58 patients. G Chir 2011; 32: 188–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Clayton MJ. Delphi: a technique to harness expert opinion for critical decision-making tasks in education. Educ Psychol 1997; 17: 373–386. [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Villiers MR, de Villiers PJ, Kent AP. The Delphi technique in health sciences education research. Med Teach 2005; 27: 639–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]