Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence and patterns of cervical spine injury (CSI) associated with maxillofacial fractures at a UK trauma centre.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted of 714 maxillofacial fracture patients presenting to a single trauma centre between 2006 and 2012.

Results

Of the 714 maxillofacial fracture patients, 2.2% had associated CSI including a fracture, cord contusion or disc herniation. In comparison, 1.0% of patients without maxillofacial trauma sustained a CSI (odds ratio: 2.2, p=0.01). The majority (88%) of CSI cases of were caused by a road traffic accident (RTA) with the remainder due to falls. While 8.8% of RTA related maxillofacial trauma patients sustained a CSI, only 2.0% of fall related patients did (p=0.03, not significant). Most (70%) of the CSIs occurred at C1/C2 or C6/C7 levels. Overall, 455, 220 and 39 patients suffered non-mandibular, isolated mandibular and mixed mandibular/non-mandibular fractures respectively. Their respective incidences of CSI were 1.5%, 1.8% and 12.8% (p=0.005, significant). Twelve patients with concomitant CSI had their maxillofacial fractures treated within twenty-four hours and all were treated within four days.

Conclusions

The presence of maxillofacial trauma mandates exclusion and prompt management of cervical spine injury, particularly in RTA and trauma cases involving combined facial fracture patterns. This approach will facilitate management of maxillofacial fractures within an optimum time period.

Keywords: Maxillofacial trauma, Facial fracture, Cervical spine injury, Road traffic accident, Fall

Maxillofacial fractures are accepted as injuries at high risk for concomitant cervical spine or spinal cord injury.1,2 The presence or absence of a cervical spine injury (CSI) has important implications in trauma patients, influencing airway management techniques, choice of diagnostic imaging studies, surgical approach and timing for repair of concomitant facial fractures. Most injuries of the cervical spine associated with facial fractures are attributed to forces transmitted directly or indirectly from the facial skeleton to the cervical bony and connective tissue structures.3,4 Those suffering high velocity injuries such as road traffic accidents (RTAs) are presumed to be at higher risk for cervical spine trauma than those sustaining lower velocity injuries as seen in falls and workplace accidents.5–8

The majority of cohort studies have reported wide variations in the incidence of CSI in maxillofacial trauma patients, ranging between 0% and 8%, in part owing to differences in the mechanism of injury, anatomical location of impact, location of trauma centre, and patient demographics including age and sex.1–4,7–16 In specific subgroups of patients such as RTA fatalities, the incidence of CSI has been cited as high as 24%.9

Trauma protocols including the Advanced Trauma Life Support ® manual stress the importance of the association between maxillofacial injury and CSI, and the catastrophic consequences that can ensue if the diagnosis is missed or its presence or absence ignored.17 However, the incidence, frequency and type of cervical spine trauma in various facial fracture patterns have been poorly delineated. This is particularly the case when considering the trauma setting in the UK, where there is a paucity of studies on large volumes of patients (>1,000 patients).

This study represents the largest recent UK analysis to date. It was based on over 700 patients across a 7-year time period. The aim was to determine the incidence and patterns of CSI associated with maxillofacial fractures admitted at a UK tertiary referral trauma centre.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed of all patients presenting with trauma between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2012 to Frenchay Hospital in Bristol. Frenchay Hospital is a tertiary referral trauma centre with a large volume of cases. All patients were divided into two cohorts: those with and without maxillofacial fractures. All patients in the former cohort presented to the maxillofacial surgery department at the same institution while patients in the latter cohort did not.

Data were collected from the departmental database and the hospital information technology coding service. Data collected common to both cohorts of trauma patients (with and without maxillofacial fractures) included demographics, spinal imaging modalities performed and the presence or absence of associated CSI. This enabled a comparative analysis of the incidence of CSI in trauma patients who had sustained maxillofacial fractures versus those who had not.

For the cohort of patients who had sustained maxillofacial trauma, more detailed data were collected. Patient charts were reviewed for mechanism of injury, type and location of maxillofacial fracture patterns, and presence and type of concomitant CSI. Furthermore, the available plain radiography including dynamic views, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were reviewed to determine the nature of the cervical spinal and maxillofacial injuries. Data were collated on airway management, diagnostic approach, and management of the CSI and the facial fractures for each of the patients.

Several reports have described an association between mandibular fractures and CSI, and these recommend routine cervical spine radiography in all patients with mandibular injuries.3,18–20 In order to assess whether this trend was replicated at our institution, maxillofacial fractures were divided into one of three anatomical groups: isolated mandibular fractures, non-mandibular fractures and mixed (mandibular and non-mandibular) fractures.

For all patients with concomitant CSI, their associated maxillofacial fractures were further categorised into skull and upper third fractures, middle third fractures, lower third fractures and combined fractures. The skull fracture group included patients with fractures of the occipital and temporal bones and of the skull base. Fractures of the upper third of the facial skeleton were defined as those involving the supraorbital rim, orbital roof and frontal bone. Middle third facial fractures included maxillary, periorbital, nasal, nasoethmoid and zygomatic fractures. Both Le Fort I and II fractures were included in the middle third category while Le Fort III fractures were included in the combined facial category.21 Lower third facial fractures were defined as mandibular and alveolar fractures along with temporomandibular joint injuries. Combined facial fractures included any combination of two or more facial fracture areas including the skull or upper third, middle third and lower third areas.

CSI was characterised according to level of injury confirmed by radiography, and included fractures, dislocations and subluxations. Cord compression, cord contusion and disc herniation were also noted.

Statistical analysis

Differences in incidence of CSI between subgroups were assessed for significance using the chi-squared test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. This was adjusted for multiple comparisons (>2 subgroups), as appropriate, by Bonferroni correction. SPSS® version 22.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, US) was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 714 patients with maxillofacial fractures were identified in the 7-year study period. The mean patient age in this group was 44 years (range: 18–84 years) and there was a male-to-female ratio of 3:2. Over the same study period, there were 3,570 patients admitted with trauma who did not sustain any maxillofacial fractures. The mean age in this group was 46 years (range: 12–86 years) and the male-to-female ratio was 3:2.

Diagnostic approach to cervical spine injury

Among the 714 patients with maxillofacial trauma, 683 (96%) had CT and 31 (4%) had plain three-view (lateral, anteroposterior and odontoid peg) x-rays as first-line imaging. Following the initial CT, MRI was performed in 201 patients (28% of the overall cohort). In those who had initial x-rays, just over half (3% of the overall cohort) underwent CT as second-line imaging. The spinal imaging modalities undertaken and the order in which they were performed for all patients is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of radiological assessment of cervical spine injury for the patients who sustained maxillofacial and non-maxillofacial trauma

| Patient cohort | Primary imaging | n | Secondary imaging | n | Further imaging | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MF trauma

(n=714) |

X-rays

No injury detected Injury detected |

31 (4%)

30 1 |

CT

Initial x-rays normal No injury detected Injury detected Initial x-rays abnormal No injury detected Injury detected |

18 (3%)

17 16 1 1 0 1 |

Dynamic x-rays (normal CT) Stability Instability MRI Previous CT normal Previous CT abnormal No soft tissue injury Soft tissue injury |

9 (1%)

9 0 1 (0%) 0 1 1 0 |

|

CT

No injury detected Injury detected |

683 (96%)

669 14 |

Dynamic x-rays (normal CT) Stability Instability MRI Initial CT normal No soft tissue injury Soft tissue injury Initial CT abnormal No soft tissue injury Soft tissue injury |

106 (15%)

106 0 201 (28%) 187 187 0 14 0 14 |

|||

|

Non-MF trauma

(n=3,750) |

X-rays

No injury detected Injury detected |

249 (7%)

246 3 |

CT

Initial x-rays normal No injury detected Injury detected Initial x-rays abnormal No injury detected Injury detected |

112 (3%)

109 106 3 3 0 3 |

Dynamic x-rays (normal CT) Stability Instability MRI Previous CT normal Previous CT abnormal No soft tissue injury Soft tissue injury |

44 (1%)

44 0 2 (0%) 0 2 1 1 |

|

CT

No injury detected Injury detected |

3,501 (93%)

3,479 22 |

Dynamic x-rays (normal CT) Stability Instability MRI Initial CT normal No soft tissue injury Soft tissue injury Initial CT abnormal No soft tissue injury Soft tissue injury |

849 (23%)

849 0 621 (17%) 599 594 5 22 2 20 |

MF = maxillofacial; X-rays = three-view (lateral, anteroposterior, odontoid peg) radiography; CT = 2mm slice helical computed tomography; dynamic x-rays = passive flexion/extension lateral radiography

Incidence of cervical spine injury

Of the 714 patients with facial fractures, 16 patients (14 men and 2 women, mean age: 49 years, range: 21–82 years) had concomitant CSI, equating to an overall incidence of 2.2%. In comparison, of the 3,570 patients admitted with trauma who did not sustain any maxillofacial fractures, 36 (1.0%) suffered CSI. This difference in incidence of CSI in patients with maxillofacial fractures versus those without was significant (odds ratio: 2.2, p=0.012).

Facial fracture management

All 16 patients with both maxillofacial and CSI had their maxillofacial fracture treated within 4 days of admission. (Twelve were treated on the same day of admission.) In those patients treated with maxillofacial surgery, Philadelphia® collars (Össur, Reykjavik, Iceland), halo braces, sand bags and tape were used for intraoperative head and neck immobilisation. There was no instance of increased neurological impairment as a result of surgical repair of the facial fractures.

Airway management in patients with cervical spine injury and facial fractures

Of the 16 patients with facial fractures and concomitant CSI, 3 were intubated at the scene and an additional 4 were intubated successfully on arrival at the hospital. One patient required an emergency cricothyroidotomy because of unsuccessful intubation and this was converted to a formal tracheostomy within 48 hours. An additional four patients underwent a tracheostomy during the trauma admission for various reasons (including expected prolonged intubation, pulmonary complications, oropharyngeal oedema, laryngotracheal injury and midfacial instability) or during operative fixation of both the upper and lower face. From the study group of 16, 12 patients (75%) required some form of airway control.

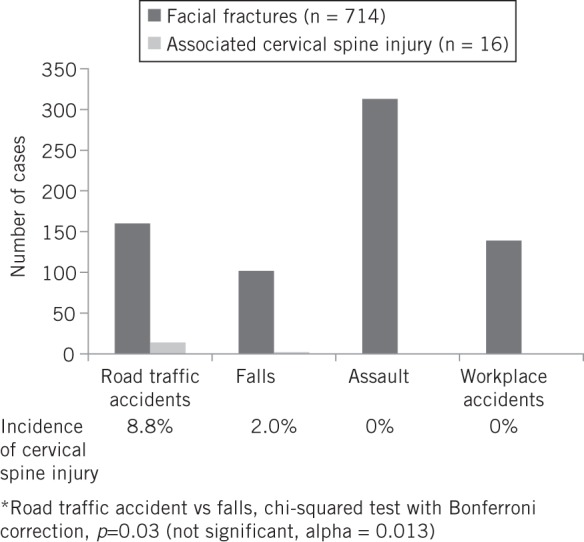

Cervical spine injury and aetiology of trauma

The incidence of CSI associated with maxillofacial fractures secondary to different aetiologies is shown in Figure 1. The incidence of CSI in patients with a facial fracture secondary to a RTA was 8.8% compared with 2.0% for patients with a facial fracture secondary to a fall (chi-squared test with Bonferroni correction, p=0.03, not significant). Of the 16 cases with concomitant CSI, 88% were due to a RTA while 12% were due to falls.

Figure 1.

Maxillofacial fractures and concomitant cervical spine injury stratified by aetiology

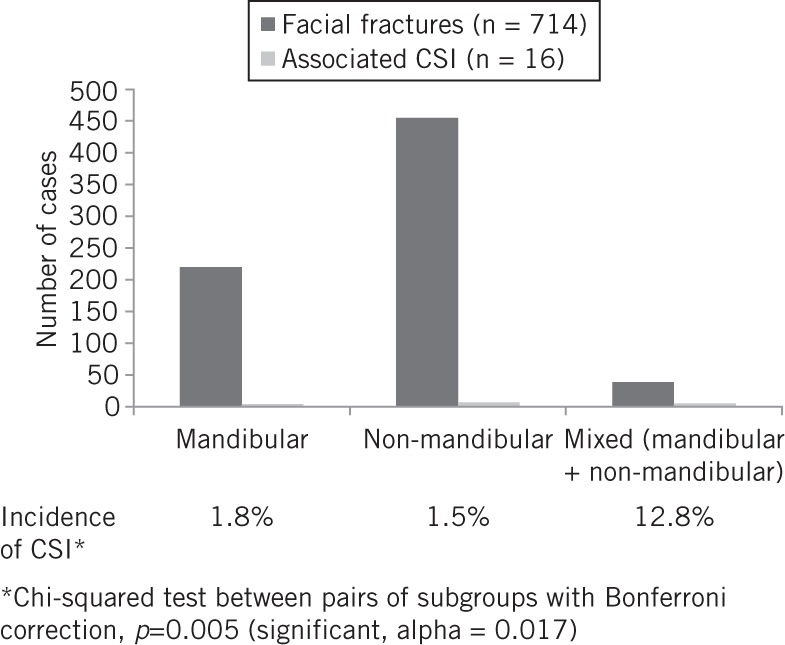

Cervical spine injury and facial fracture patterns

Overall, 455 patients suffered non-mandibular fractures, 220 had isolated mandibular fractures, and 39 had a mixed mandibular and non-mandibular fracture pattern, with corresponding incidences of CSI of 1.5%, 1.8% and 12.8% respectively (chi-squared test with Bonferroni correction, p=0.005, significant) (Fig 2). Over half of the patients with concomitant CSI (9/16, 56%) had a combined maxillofacial fracture pattern.

Figure 2.

Maxillofacial fractures and concomitant cervical spine injury (CSI) stratified by facial region

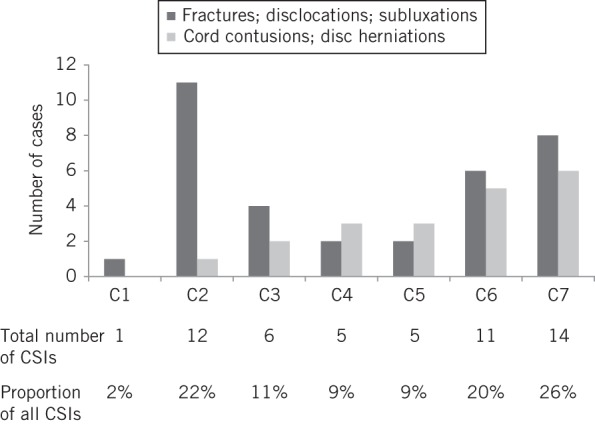

Cervical spine injuries according to level of injury

The 16 patients with concomitant CSI had a total of 54 CSIs (Fig 3). Bony fractures, cervical subluxations and dislocations accounted for 63% of the injuries whereas 37% were related to disc herniation and cord contusions. The most common areas of injury involved C1/C2 and C6/C7 levels, accounting for 24% and 46% of the injuries respectively. Therefore, 70% of all CSI occurred at the C1/C2 and C6/C7 levels.

Figure 3.

Type and frequency of cervical spine injuries (CSIs) according to level of injury (vertebral body level for bony injury and cord contusion; lower adjacent intervertebral disc level for disc herniation)

Discussion

This study represents the largest UK analysis to date looking at the incidence of CSI in patients with traumatic maxillofacial fractures. Our study specifically analysed all patients from a designated, urban trauma hospital. A low incidence of CSI associated with maxillofacial fractures was found (2.2%). This is consistent with the majority of studies in the literature, which report incidences ranging from 0% to 8%.1–4,7–16,22–25 Additionally, in our study, trauma patients with maxillofacial fractures had a twofold higher incidence of concomitant CSI compared with trauma patients without maxillofacial injury. This finding has been replicated in several studies23–26 but not all.13 Transmitted forces in the maxillofacial injured patient from the skull and facial skeleton to the cervical spine may explain our observed trend.

Any patient with a maxillofacial injury should be suspected of having a CSI, mandating immobilisation and imaging of the cervical spine. Plain lateral, anteroposterior and odontoid radiography has a combined sensitivity of 90%,27,28 and will not detect all CSI. CT further improves sensitivity beyond 99%.29

Historically, up until five years ago, initial plain radiography was performed. Following the implementation in 2008 of the British Orthopaedic Association Standards for Trauma guidelines in major trauma centres across the UK,30 thin slice helical CT from the skull base to T1 has become the routine first-line imaging modality performed to assess CSI in trauma patients. This is the case in our institution.

For blunt trauma patients clinically suspicious of CSI with normal initial plain radiography or CT, MRI is considered by some as the gold standard for clearing the cervical spine.31 In our study, CSI cases were identified using a combination of plain films (all cases), CT (15 out of 16 cases) and MRI (1 case). Our hospital’s policy is to exclude CSI using CT or MRI in all patients with maxillofacial fractures as a result of high energy impact or associated fractures in other areas of the body.

The presence of CSI may require treatment to be modified and can delay the surgical repair of maxillofacial fractures. This possibility may be minimised by prompt consultation with the neurosurgical service to optimise stabilisation of the CSI together with performing careful induction of anaesthesia using endoscopically guided endotracheal intubation and open reduction and internal fixation of facial fractures with avoidance of hyperextension or rotation of the head. These factors ensured that, in our study, 12 out of 16 patients had maxillofacial surgery on the same day of admission and all patients had surgery within 4 days of admission (ie within an optimum time period and without any treatment delay).

Cervical spine injury and aetiology of trauma

The vast majority (88%) of CSI cases were associated with a RTA. Furthermore, the incidence of CSI was fourfold higher for those patients who sustained a maxillofacial fracture due to a RTA (8.8%) than cases due to a fall (2.0%) although this difference was not statistically significant. The association of CSI with RTAs (as opposed to falls and other traumatic scenarios) most likely reflects the greater velocity and therefore force of impact to the face since force is the product of mass and acceleration. This mechanical force is transmitted from the facial skeleton to the cervical spine, causing spinal injury.3,4 In particular, when a seatbelt is not worn, the driver is subject to indirect cervical spine trauma as the head is easily hyperflexed or hyperextended by an impact with the windshield, steering wheel or other structures inside the vehicle.17

Cervical spine injury and facial fracture pattern

Our study revealed an incidence of CSI associated with a mixed (mandibular and non-mandibular) maxillofacial fracture pattern that was eight times higher than that associated with a non-mandibular or isolated mandibular fracture pattern. This significant trend is supported by a study from 2010 looking at over 1.3 million trauma patients from the US and Puerto Rico.22 Furthermore, in our study, 56% of patients with CSI had a combined maxillofacial fracture pattern. These findings likely reflect the greater force of injury involved when two or more facial regions have been fractured as compared with one isolated facial region, which is in turn transmitted to the cervical spine.

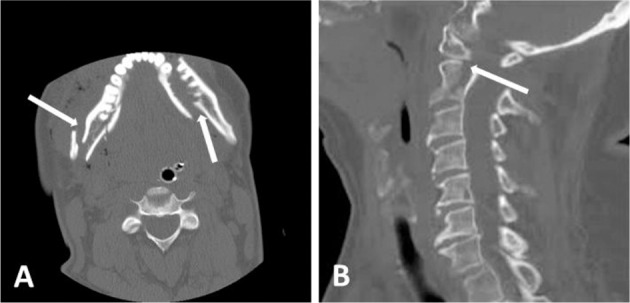

Various authors have reported a correlation between mandibular fractures and CSI, with the incidence of concomitant CSI with mandibular fractures ranging from 1.07%25 to 2.6%.3 Our study’s incidence of 1.8% (4/220) lies within this range. A patient in our study with a mandibular fracture and concomitant CSI is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Computed tomography of a 68-year-old man involved in a road traffic accident with severe jaw and neck pain and no neurological deficit, showing a comminuted mandibular fracture (A) and concomitant C2 fracture (B)

Lalani and Bonanthaya described a CSI model in relation to the maxillofacial fracture site.20 They suggest injuries to upper cervical spine segments are associated with lower third facial fractures, principally mandibular fractures, whereas injuries to the lower cervical spine segments are associated with middle third facial fractures. Our study lends some support to this model in that three of the four cases of CSI associated with isolated mandibular fractures occurred at C2 and the remaining case at C1. An example of a case of middle third facial fractures with concomitant lower segment CSI is shown in Figure 5.

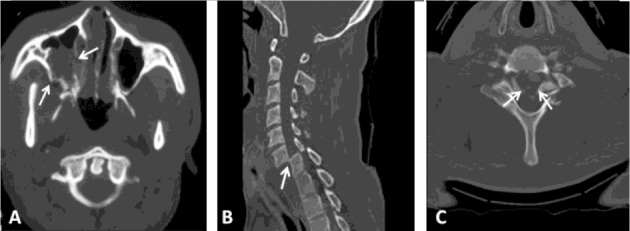

Figure 5.

Computed tomography of a 54-year-old male unrestrained driver involved in a road traffic accident, with severe facial injuries, Glasgow coma scale score of 10 and quadriplegia with spinal shock. He suffered comminuted fractures of the medial and lateral walls of the right maxillary sinus with haematoma (arrows) (A). The nasal septum and medial wall of the left maxillary sinus were also fractured. He had concomitant bifacetal fracture dislocations at C6/C7 (B) and impingement of the spinal cord at C6/C7 (C). He underwent closed reduction and application of a halo vest for his cervical spine injury, and reduction and fixation of his maxillary fractures. He subsequently underwent anterior spinal fusion and discectomy.

A high velocity impact is required to fracture the structures of the frontal and supraorbital ridges whereas weaker forces can fracture the skull.32 This discrepancy may account for the higher frequency of CSI seen with isolated upper third versus other regional facial fractures.10 With only 16 CSI patients in our study, we found no reliable correlation between facial fracture region and incidence or level of CSI.

Cervical spine injuries according to level of injury

CSI occurred principally at two levels, C1/C2 and C6/C7, accounting for 70% of all CSI. This finding is supported by Elahi et al,who showed that 67% of 124 CSIs associated with maxillofacial trauma occurred at the C1/C2 and C6/C7 levels.10 One biomechanical explanation is that the loose articular capsules of the C1/C2 joint, together with shallow facets of the atlas, produce the greatest degree of inherent instability in the cervical spine, allowing approximately half of all its flexion, extension and rotational movement.33 – 35 The relatively greater degree of rotational movement permitted in the cervicothoracic junction at C6/C7 may account for the higher frequency of injuries found at this level.33 35

Our study also showed an increasing frequency of cervical disc herniation/cord contusion as one travels in a cephalic to caudal direction (44% incidence at C6/C7 vs 8% at C1/C2). This difference may be due to accentuation of direct and indirect forces transmitted from the facial skeleton further down the spinal cord.3 Another explanation asserts that the significant ligamentous anatomy of the C1/C2 region, compared with lower levels of the subaxial cervical spine, serves to protect the spinal cord from injury.35–38 A further biomechanical mechanism states that the smaller diameter of the cervical spinal canal at C6/C7 versus that at C1/C2 is associated with an increased risk of cord injury.39,40

It is not clear from the available literature on facial trauma what the true patterns of CSI are and why it occurs. This is partly due to the heterogeneity of previous cohort studies with regard to mechanism of injury, anatomical location of impact, location of trauma centre, imaging modalities used, and patient demographics including age and sex. The differences in these factors between studies have led to inconsistent observations of injury patterns.1–4,7–16 In our study at a single tertiary centre for trauma, we observed several trends in CSI as described above, for which we have provided biomechanical explanations.

Study limitations

This was a retrospective study prone to the biases associated with this methodology. We acknowledge that given the low incidence of CSI, our series of 714 patients with maxillofacial trauma represents a small volume of patients from which to analyse the association between the two entities – only 16 patients were found to have CSI. As a result, small subgroup sizes with very low frequencies of CSI may have introduced a type 2 statistical error. Furthermore, we recognise that numerous international series have analysed a number of patients that was 4–5 times the size of our group. Analysis of a larger cohort (>2,000 patients) would have strengthened our study.

Conclusions

Although our reported incidence of CSI associated with maxillofacial fractures is low, it has implications for mandatory exclusion and prompt management of CSI (particularly in the setting of RTAs) and maxillofacial trauma involving combined facial fracture patterns. Prompt referral to neurosurgeons will optimise treatment of CSI, thereby facilitating management of maxillofacial fractures within an optimum time period. The highest frequency of CSI was observed at the C1/C2 and C6/C7 levels, and there was increasing frequency of cervical cord contusion and disc herniation at progressively lower levels of the cervical spine.

References

- 1. Baker AB, Mackenzie W. Facial and cervical injuries. Med J Aust 1976; 1: 236–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beirne JC, Butler PE, Brady FA. Cervical spine injuries in patients with facial fractures: a 1-year prospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1995; 24: 26–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ardekian L, Gaspar R, Peled M et al. Incidence and type of cervical spine injuries associated with mandibular fractures. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma 1997; 3: 18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davidson JS, Birdsell DC. Cervical spine injury in patients with facial skeletal trauma. J Trauma 1989; 29: 1,276–1,278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haisová L, Krámová I. Facial bone fractures associated with cervical spine injuries. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1970; 30: 742–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lewis VL, Manson PN, Morgan RF et al. Facial injuries associated with cervical fractures: recognition, patterns, and management. J Trauma 1985; 25: 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Merritt RM, Williams MF. Cervical spine injury complicating facial trauma: incidence and management. Am J Otolaryngol 1997; 18: 235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams J, Jehle D, Cottington E, Shufflebarger C. Head, facial, and clavicular trauma as a predictor of cervical-spine injury. Ann Emerg Med 1992; 21: 719–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bucholz RW, Burkhead WZ, Graham W, Petty C. Occult cervical spine injuries in fatal traffic accidents. J Trauma 1979; 19: 768–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elahi MM, Brar MS, Ahmed N et al. Cervical spine injury in association with craniomaxillofacial fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 121: 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haug RH, Wible RT, Likavec MJ, Conforti PJ. Cervical spine fractures and maxillofacial trauma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1991; 49: 725–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mulligan RP, Friedman JA, Mahabir RC. A nationwide review of the associations among cervical spine injuries, head injuries, and facial fractures. J Trauma 2010; 68: 587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oller DW, Meredith JW, Rutledge R et al. The relationship between face or skull fractures and cervical spine and spinal cord injuries: a review of 13,834 patients. Accid Anal Prev 1992; 24: 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reiss SJ, Raque GH, Shields CB, Garretson HD. Cervical spine fractures with major associated trauma. Neurosurgery 1986; 18: 327–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roccia F, Cassarino E, Boccaletti R, Stura G. Cervical spine fractures associated with maxillofacial trauma: an 11-year review. J Craniofac Surg 2007; 18: 1,259–1,263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sinclair D, Schwartz M, Gruss J, McLellan B. A retrospective review of the relationship between facial fractures, head injuries, and cervical spine injuries. J Emerg Med 1988; 6: 109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. American College of Surgeons. ATLS® Student Course Manual. 8th edn. Chicago: ACS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andrew CT, Gallucci JG, Brown AS, Barot LR. Is routine cervical spine radiographic evaluation indicated in patients with mandibular fractures? Am Surg 1992; 58: 369–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jung HW, Lee BS, Kwon YD et al. Retrospective clinical study of mandible fractures. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014; 40: 21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lalani Z, Bonanthaya KM. Cervical spine injury in maxillofacial trauma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997; 35: 243–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rhea JT, Mullins ME, Novelline RA. The Face. In:Rogers LF. Radiology of Skeletal Trauma. 3rd edn, vol 1 London: Churchill Livingstone; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mulligan RP, Mahabir RC. The prevalence of cervical spine injury, head injury, or both with isolated and multiple craniomaxillofacial fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 126: 1,647–1,651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Piatt JH. Detected and overlooked cervical spine injury among comatose trauma patients: from the Pennsylvania Trauma Outcomes Study. Neurosurg Focus 2005; 19: E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tian HL, Guo Y, Hu J et al. Clinical characterization of comatose patients with cervical spine injury and traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 2009; 67: 1,305–1,310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tu PH, Liu ZH, Yang TC et al. Delayed diagnosis of traumatic cervical subluxation in patients with mandibular fractures: a 5-year retrospective study. J Trauma 2010; 69: E62–E65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fujii T, Faul M, Sasser S. Risk factors for cervical spine injury among patients with traumatic brain injury. J Emerg Trauma Shock 2013; 6: 252–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ross SE, Schwab CW, David ET et al. Clearing the cervical spine: initial radiologic evaluation. J Trauma 1987; 27: 1,055–1,060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Besman A, Kaban J, Jacobs L, Jacobs LM. False-negative plain cervical spine x-rays in blunt trauma. Am Surg 2003; 69: 1,010–1,014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morris CG, McCoy E. Clearing the cervical spine in unconscious polytrauma victims, balancing risks and effective screening. Anaesthesia 2004; 59: 464–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. British Orthopaedic Association. BOAST 2: Spinal Clearance in the Trauma Patient. London: BOA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Muchow RD, Resnick DK, Abdel MP et al. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the clearance of the cervical spine in blunt trauma: a meta-analysis. J Trauma 2008; 64: 179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Luce EA, Tubb TD, Moore AM. Review of 1,000 major facial fractures and associated injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg 1979; 63: 26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schafer RC. The Cervical Spine. In:Schafer RC. Clinical Biomechanics. 2nd edn. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 34. White AA, Panjabi MM. Kinematics of the Spine. In:White AA, Panjabi MM. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine. 2nd edn. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Torretti JA, Sengupta DK. Cervical spine trauma. Indian J Orthop 2007; 41: 255–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sekhon LH, Fehlings MG. Epidemiology, demographics and pathophysiology of acute spinal cord injury. Spine 2001; 26: S2–S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Joaquim AF, Ghizoni E, Tedeschi H, Lawrence B et al. Upper cervical injuries – a rational approach to guide surgical management. J Spinal Cord Med 2014; 37: 139–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Syre P, Petrov D, Malhotra NR. Management of upper cervical spine injuries: a review. J Neurosurg Sci 2013; 57: 219–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang L, Chen HB, Wang Y et al. Cervical spinal canal narrowing and cervical neurological injuries. Chin J Traumatol 2012; 15: 36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kang JD, Figgie MP, Bohlman HH. Sagittal measurement of the cervical spine in subaxial fractures and dislocations. An analysis of two hundred and eighty-eight patients with and without neurological deficits. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994; 76: 1,617–1,628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]