Abstract

Laryngeal clefts are rare congenital malformations of the posterior laryngotracheal wall that lead to an abnormal communication between the airway and pharyngo-oesophageal tract. The condition is almost universally identified during infancy with minor laryngeal clefts very rarely diagnosed in adulthood. We present our tertiary centre’s experience of a large laryngeal cleft presenting at an advanced age, with the aim of increasing awareness of this correctible cause of respiratory distress and aspiration in adults.

Keywords: Adult, Laryngeal cleft, Laryngotracheal cleft, Laryngeal disease

Laryngeal clefts are rare congenital malformations of the posterior laryngeal or laryngotracheal wall that lead to an abnormal communication between the airway and pharyngo-oesophageal tract. The condition presents in early childhood and is extremely rare in adults, with only a few case reports in the literature. The consequences of this breach can vary widely depending on the caudal extent of the defect, from being largely asymptomatic to life threatening lung damage. Early diagnosis and treatment is paramount to improving the quality of life and survival of affected patients.

Case report

A 43-year-old woman presented to the ear, nose and throat department with acute airway compromise and a past medical history of asthma since childhood. Following stabilisation with intravenous steroids, she underwent microlaryngotracheoscopy under general anaesthesia. This revealed a type 3 laryngeal cleft with oedematous soft tissue on either side of the cleft obstructing her airway (Fig 1). Further investigations included a contrast swallow and computed tomography (CT), which showed a vertical midline cleft in the cricoid cartilage posteriorly (Figs 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Endoscopic clinical photograph of the type 3 laryngeal cleft with redundant mucosa hiding the defect

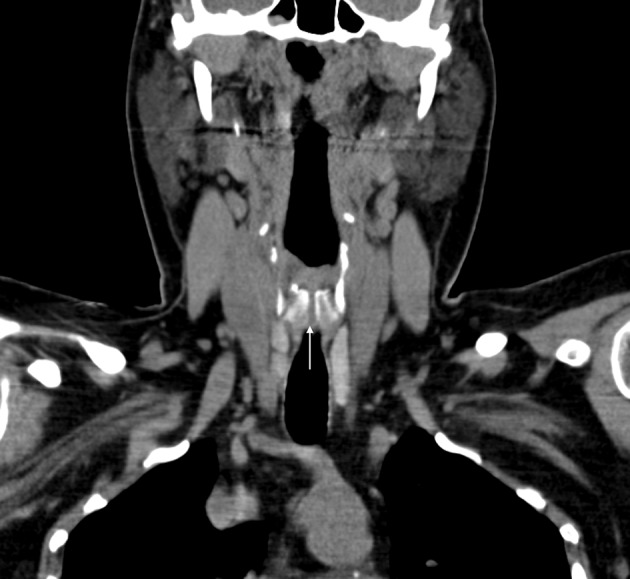

Figure 2.

Coronal computed tomography of the neck demonstrating the laryngeal cleft through the full length of the cricoid cartilage

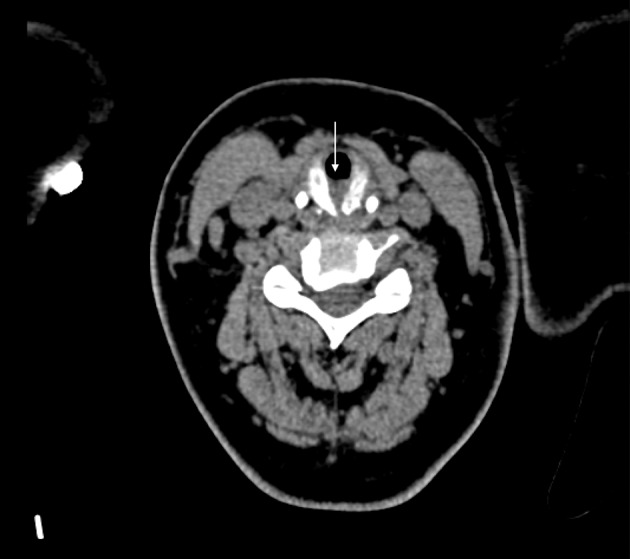

Figure 3.

Axial computed tomography of the neck reformatted in the plane of the cricoid cartilage demonstrating the laryngeal cleft with interposed soft tissue encroaching into the tracheal airway

The size of the cleft and worsening airway compromise mandated urgent open surgical repair of the laryngeal cleft rather than an endoscopic approach. Laryngofissure was performed four weeks later, revealing a 3cm laryngeal cleft extending through the cricoid cartilage into the cervical trachea. The edges of the cleft were freshened and closed in two layers with an interposed fascia lata graft. A temporary tracheostomy was inserted below the level of the reconstruction as well as a subcutaneous corrugated drain to prevent surgical emphysema.

Following surgery, the patient received prophylactic antibiotics, proton pump inhibitor therapy and nasogastric feeding. She was decannulated seven days later and discharged. She presented again 26 days following surgery with dysphagia and pyrexia secondary to an infected graft, which was treated successfully with antibiotics. Fibreoptic nasendoscopy revealed slough and granulation tissue at the site of cleft repair. She subsequently underwent microlaryngoscopy and laser ablation (CO2 laser 8 watts) at six weeks following reconstruction. Further outpatient review over the next three years was uneventful.

Discussion

The aetiology of laryngeal clefts remains obscure. However, their incidence has been associated with both environmental and genetic factors. Associations include maternal alcohol and drug abuse, Opitz G/BBB syndrome, Pallister–Hall syndrome, 22q11 microdeletion and various non-syndromic congenital abnormalities.1

The tracheo-oesophageal folds fuse in a caudocranial direction between the fifth and seventh weeks of embryological development. Failure of these folds to fuse is thought to lead to a paucity of the tracheo-oesophageal septum and therefore the development of a laryngeal cleft. The extent and severity of this depends on the point at which fusion arrests.2

The inferior extension of a laryngeal cleft is an indicator of its severity and prognosis, and underlies the Benjamin and Inglis classification system:3

Type 1 – supraglottic cleft

Type 2 – cleft extending below the vocal folds into the cricoid cartilage

Type 3 – cleft extending through the cricoid cartilage and into the cervical trachea

Type 4 – cleft extending into the thoracic trachea

Clinical presentation

Laryngeal clefts can present in a variety of ways depending on the severity of the malformation. Type 1 clefts are characterised by mild to moderate symptoms that can include stridor, a toneless or hoarse cry in infants and swallowing disorders. Dysphagia and aspiration predominate in the presentation of type 2 and 3 clefts while type 4 clefts often lead to respiratory distress.4

The vast majority of laryngeal clefts present in childhood, with a cited incidence of 1 in 10,000–20,000 live births. The average age of diagnosis in childhood depends on the severity of clinical symptoms and the type of laryngeal cleft. However, a few cases of isolated laryngeal clefts have been identified in adults, with reports made of a type 1 laryngeal cleft diagnosed in a 19-year-old and a type 2 laryngeal cleft in a 25-year-old.5

This case is highly unusual given the age of the patient and stage of the cleft. To our knowledge, this is oldest person in the English language literature with an isolated laryngeal cleft.

Diagnosis

Given the rarity of the condition, the range of possible presentations and the subtlety of endoscopic signs, diagnosing laryngeal clefts can pose a challenge. Visualisation of the larynx with microlaryngoscopy under general anaesthesia is the gold standard for diagnosis of laryngeal clefts. The posterior glottis should be inspected carefully and palpated to identify minor clefts that may be masked by redundant mucosa, and the length of the cleft must be assessed to determine its type. Associated anomalies such as laryngomalacia, tracheobronchial dyskinesia, tracheobronchomalacia, tracheo-oesophageal fistula and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease should also be excluded.

In addition to endoscopic examination, diagnostic workup of laryngeal clefts should include radiological assessment. Chest x-ray is important to exclude aspiration pneumonia. Water soluble contrast swallow studies can demonstrate the flow of contrast into the trachea in the presence of a laryngeal cleft. CT of the neck and chest can demonstrate a communication or deficiency in soft tissue between the oesophagus and trachea.

Treatment

The management of laryngeal cleft is dependent on its type, associated anomalies and the patient’s respiratory status. An isolated asymptomatic submucosal cleft may be managed conservatively with dietary modifications and instructions on safe swallowing. Conversely, a patient with severe laryngeal cleft, clinically apparent aspiration and poor respiratory status would be a typical candidate for surgical repair.

The surgical approach and urgency of surgery also depends on the severity of symptoms, type of cleft and the presence of associated anomalies. The endoscopic approach is the first choice method for repair of type 1, 2 and the majority of type 3 laryngeal clefts given the lower morbidity associated with this technique. However, open surgery is indicated in the repair of all type 4, some type 3 laryngeal clefts and in cases where an endoscopic approach has failed.

Conclusions

Laryngeal clefts represent a very rare cause of dyspnoea and aspiration in the adult population. Awareness of the condition and its potential complications is essential for the safe management of these patients.

References

- 1. Pezzettigotta S, Leboulanger N, Roger G et al. Laryngeal cleft. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2008; 41: 913–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blumberg JB, Stevenson JK, Lemire RJ, Boyden EA. Laryngotracheoesophageal cleft, the embryologic implications: review of the literature. Surgery 1965; 57: 559–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benjamin B, Inglis A. Minor congenital laryngeal clefts: diagnosis and classification. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1989; 98: 417–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Myer CM, Cotton RT, Holmes DK, Jackson RK. Laryngeal and laryngotracheoesophageal clefts: role of early surgical repair. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1990; 99: 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Condon LT, Salvage DR, Stafford ND. Type-2 submucosal posterior laryngeal cleft diagnosed on CT scan. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2003; 260: 361–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]