ABSTRACT

The influenza virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase catalyzes genome replication and transcription within the cell nucleus. Efficient nuclear import and assembly of the polymerase subunits PB1, PB2, and PA are critical steps in the virus life cycle. We investigated the structure and function of the PA linker (residues 197 to 256), located between its N-terminal endonuclease domain and its C-terminal structured domain that binds PB1, the polymerase core. Circular dichroism experiments revealed that the PA linker by itself is structurally disordered. A large series of PA linker mutants exhibited a temperature-sensitive (ts) phenotype (reduced viral growth at 39.5°C versus 37°C/33°C), suggesting an alteration of folding kinetic parameters. The ts phenotype was associated with a reduced efficiency of replication/transcription of a pseudoviral reporter RNA in a minireplicon assay. Using a fluorescent-tagged PB1, we observed that ts and lethal PA mutants did not efficiently recruit PB1 to reach the nucleus at 39.5°C. A protein complementation assay using PA mutants, PB1, and β-importin IPO5 tagged with fragments of the Gaussia princeps luciferase showed that increasing the temperature negatively modulated the PA-PB1 and the PA-PB1-IPO5 interactions or complex stability. The selection of revertant viruses allowed the identification of different types of compensatory mutations located in one or the other of the three polymerase subunits. Two ts mutants were shown to be attenuated and able to induce antibodies in mice. Taken together, our results identify a PA domain critical for PB1-PA nuclear import and that is a “hot spot” to engineer ts mutants that could be used to design novel attenuated vaccines.

IMPORTANCE By targeting a discrete domain of the PA polymerase subunit of influenza virus, we were able to identify a series of 9 amino acid positions that are appropriate to engineer temperature-sensitive (ts) mutants. This is the first time that a large number of ts mutations were engineered in such a short domain, demonstrating that rational design of ts mutants can be achieved. We were able to associate this phenotype with a defect of transport of the PA-PB1 complex into the nucleus. Reversion substitutions restored the ability of the complex to move to the nucleus. Two of these ts mutants were shown to be attenuated and able to produce antibodies in mice. These results are of high interest for the design of novel attenuated vaccines and to develop new antiviral drugs.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza A viruses (IAVs) are important viral respiratory pathogens of humans. These viruses are members of the Orthomyxoviridae family; they possess a negative-sense single-stranded segmented RNA genome (reviewed in reference 1). The three largest segments encode the three subunits of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: the two basic proteins PB1 and PB2 and the acidic subunit PA (reviewed in reference 2). In contrast to many RNA viruses, the influenza virus genome is transcribed and replicates in the nucleus of infected cells. The polymerase subunits, which are produced in the cytoplasm, are then imported into the nucleus and assembled into a functional trimer (3, 4). Based on in vitro assembly and cellular localization studies (5, 6, 7, 8), it was shown that PA and PB1 form a dimer in the cytoplasm, which is imported into the nucleus separately from PB2. Once in the nucleus, the PB1-PA dimer associates with PB2 to form the heterotrimeric polymerase. The nucleotide polymerization activity is common to both replication and transcription, with an additional cap-snatching function being employed during transcription to steal short 5′-capped RNA primers from host mRNAs (9).

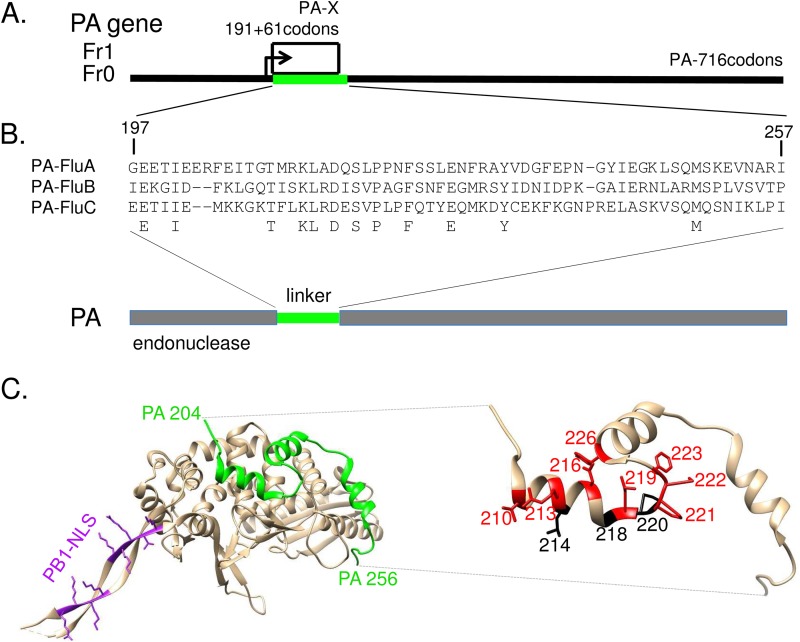

The PB1 subunit functions as the polymerase catalytic subunit. It presents the conserved motifs and finger and palm subdomains characteristic of negative-strand RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (10, 11), binds to the promoter sequences of the viral and complementary RNAs (12, 13), and catalyzes RNA chain elongation (14). The PB2 subunit is responsible for recognition and binding of the cap structure of host mRNAs (15, 16). The PA subunit is divided into two main domains structurally well defined, the endonuclease domain (amino acids 1 to 197) and a large C-terminal domain (amino acids 257 to 716) that binds the 15 first residues of the PB1 subunit (Fig. 1). The PA endonuclease and the PB2 cap-binding domains act synergistically to promote cap-snatching-dependent transcription (17). The endonuclease fold and its active site arrangement are similar to those of the PD-(D/E)XK family of nucleases (18, 19). The PA C-terminal domain is also involved in viral mRNA transcription: a His-to-Ala substitution at position 510 allowed replication activity, while transcriptional activity of the mutant was negligible (20). These two functional and structured domains are linked through a 60-amino-acid-long linker (residues 197 to 257) that wraps around the external face of the PB1 fingers and palm domain. In particular, residues 201 to 257, which include three helical segments, lie across the surface of PB1 making numerous, often conserved, intersubunit contacts that are both hydrophobic and polar in nature (11, 17) (Fig. 1). A second protein, named PA-X, is expressed from the PA segment by ribosomal frameshifting (Fig. 1) (21). It comprises the endonuclease domain of PA fused to a C-terminal domain (41 to 61 residues) encoded by the X open reading frame (ORF) and represses cellular gene expression. The X ORF overlaps a large part of the reading frame encoding the linker between the endonuclease and the PB1-binding domains of PA.

FIG 1.

The polypeptides encoded by IAV segment 3. (A) PA and PA-X ORF structures, showing full-length PA in frame 0 and the X-ORF in frame 1, with their codon numbers indicated. PA-X results from a ribosomal frameshift (21). (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of influenza virus A, B, and C PA/P3 linker domains. Conserved residues are indicated in bold. (C, left panel) Ribbon diagram of the PA linker (green) interacting with PB1. Note the presence of three PA helices interacting with PB1. Residues from the PB1 nuclear localization signals are colored magenta. (Right panel) Ribbon diagram of the PA linker indicating the positions at which substitutions inducing a ts phenotype (red) or an absence of rescue (black) were found.

Generation of temperature-sensitive (ts) mutants and their characterization are powerful tools to investigate essential steps in the virus life cycle. For instance, a ts mutation in the NS1 gene was associated with a late event in virus morphogenesis (22). More recently, a ts mutation in NP allowed identification of a late role for NP in the formation of infectious particles (23). A number of ts mutations have been identified in the three polymerase subunits, PA, PB1, and PB2 (24, 25, 26, 27), and the determinism of the corresponding phenotypes often remains elusive. One of these ts mutations is an amino acid change from Leu to Pro at residue 226 of PA and is associated with a defect in polymerase complex assembly (28), suggesting the functional importance of the PA linker domain in this assembly process.

Here, we investigated the structure and the function of the PA linker. We determined its structure in the absence of other viral components. Mutational analysis allowed identification of mutations that did not support viral growth as well as several others that displayed a ts− phenotype. We studied the consequences of these mutations on the replication machinery, the import of the PA-PB1 dimer into the nucleus, the association of PA and PB1 subunits with each other and with the β-importin IPO5 (formerly named RanBP5 [29]), and on virus pathogenesis. We also identified mutations that were able to reverse the temperature sensitivity and the defect in PB1 nuclear import of ts mutants engineered in the PA linker.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

This study was carried out in accordance with INRA guidelines in compliance with European animal welfare regulations. The protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Centre de Recherches de Jouy-en-Josas (COMETHEA; protocol number 12-060) under the relevant institutional “Direction départementale de la Protection des Populations des Yvelines” (permit number A78-167). All experimental infection procedures were performed in biosafety level 2 facilities.

Cells.

293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin. Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were maintained in minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, glutamine, and antibiotics. Cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Generation of recombinant influenza viruses.

Influenza virus A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) was used in this study. Wild-type (wt) and PA mutant viruses were generated by reverse genetics using the 12-plasmid reverse genetics system kindly provided by G. Brownlee (30). Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out on the PA gene by using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The viruses were prepared as previously described (31). Briefly, a 1-day coculture of 293T and MDCK cells (seeding of 3 × 105 and 4 × 105 cells, respectively, in P6 plates) was transfected with a plasmid mixture (0.25 μg per plasmid) using Fugene HD (Promega) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. At 48 h posttransfection, cell supernatants were harvested and used to inoculate MDCK cells for the production of rescued virus stocks. The polymerase and NP genes of the viruses were sequenced to validate the presence of mutations.

Kinetics of replication.

MDCK cells were infected with wild-type WSN or PA mutant viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10−2 at 33, 37, or 39.5°C. At different times postinfection, culture supernatants were collected and subjected to plaque assays in MDCK cells for virus titration at 33°C. In some experiments, plaque assays were carried out on the same virus suspensions at 33, 37 and 39.5°C.

Minireplicon assay.

293T cells were seeded in P96 wells (7 × 104 cells/well) and transfected on day 1 with plasmids driving the expression of the viral proteins PB1, PB2, PA mutants, NP, and pPolI-WSN-NA-firefly luciferase as previously described (32). Plasmid pRSV-βGal (Promega) was used as an internal control for transfection efficiency. As a negative control, 293T cells were transfected with the same plasmids, with the exception of the PA expression plasmid. After transfection, the cells were incubated at 33°C, 37°C, or 39.5°C for 48 h, and then luciferase activity was measured with d-luciferin sodium salt (Sigma) on a Tecan Infinite M200Pro luminometer according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Protein location assay.

293T cells seeded on glass coverslips were cotransfected with plasmids derived from the pCI vector (Promega) and expressing various forms of the PA, PB1, and PB2 proteins, including the fusion protein PB1-GFP (green fluorescent protein). At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehye in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature for 10 min with 3 μM 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, mounted on glass plates (Pro Long Gold; Invitrogen), and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon TE200). Images were processed using MetaVue software (Molecular Devices). A rabbit serum directed against the PA domain (residues 197 to 257) was used to reveal PA expression and location.

Protein-protein interaction assay.

The protein-protein interaction assay was based on the complementation of two trans-complementing fragments of Gaussia princeps luciferase, Gluc1 and Gluc2, as described in reference 33. Interaction-mediated luciferase activity was measured in cultured cells transiently expressing a protein fused to Gluc1 and another one fused to Gluc2. The pCI-PA-LL-Gluc1 plasmid and its derivatives (pCI-PA214P-Gluc1, pCI-PA216P-Gluc1, pCI-PA219P-Gluc1, and pCI-PA223P-Gluc1) and pCI-PB1-SL-Gluc2 plasmids were obtained via modification of pCI-PA and pCI-PB1 by using standard PCR, site-directed mutagenesis, and cloning procedures in order to fuse the following sequences to the 3′ end of the PA ORFs and PB1 ORF: a long peptidic linker, AAAGGGGSGGGGS (LL), followed by Gluc1 for PA and a short peptidic linker, AAAGGS (SL), followed by Gluc2 for PB1. The Gateway-derived Gluc2-IPO5 expression plasmid was described previously (34). 293T cells were seeded at a concentration of 3 × 104 cells per well in 96-well white plates (Greiner Bio-One, Courtaboeuf, France). After 24 h, the cells were transfected in triplicate with the indicated combinations of pCI-derived (25 ng) and Gateway-derived (100 ng) plasmids by using polyethyleneimine (Polyscience Inc., Le Perray-en-Yvelines, France) and incubated at 35°C or 39.5°C. At 17 h posttransfection, cells were mildly rinsed in Ca2+/Mg2+-Dulbecco's PBS, and 40 μl of Renilla lysis buffer (Promega) was added to each well. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, the Gaussia princeps luciferase enzymatic activity was measured using Renilla luciferase assay reagent (Promega) and a Berthold Centro XS luminometer (Renilla luminescence counting program; integration time of 10 s after injection of 50 μl of the reagent). Normalized luminescence ratios (NLRs) were calculated as described previously (33). Binding between PA mutants and IPO5 was assayed in the presence or absence of untagged PB1. To calculate the NLRs, control samples were pGluc1 plus pGluc2-IPO5 (with or without PB1) and pGluc2 plus pCI-PA-Gluc1.

Mouse strains.

Female C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were purchased from the Centre d'Elevage R. Janvier (Le Genest Saint-Isle, France) and were used around 8 weeks of age. Mouse strains were bred in an animal facility under pathogen-free conditions. Mice were fed with normal mouse chow and water ad libitum and were reared and housed under standard conditions with air filtration. For infection experiments, mice were housed in cages inside stainless steel isolation cabinets that were ventilated under negative pressure with HEPA-filtered air.

Animal infection and fluid collection.

Mice were anesthetized by a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (1 and 0.2 mg per mouse, respectively) and infected intranasally with 50 μl of PBS containing a serial dilution of a suspension containing 108 PFU of IAV, as previously described (35). To determine the 50% lethal doses (LD50s), groups of 5 mice were infected with different dilutions of virus (wild type and mutants) and observed for signs of morbidity and death over 18 days. At day 18, surviving mice were killed and blood was collected.

Titration of antiviral antibodies.

Individual mouse sera were assayed for IAV-specific antibodies (total Ig) in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Microtiter plates (Immulon 2HB; ThermoLabsystems) were coated overnight at 4°C with IAV antigen (200 ng per well in 100 μl carbonate-bicarbonate buffer [0.1 M, pH 9.5]). Plates were washed five times with PBS–0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) between each step of the assay. After coating, the remaining protein binding sites were saturated with 5% FCS in PBS–0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T–FCS) for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were serially diluted 3-fold in PBS-T–FCS starting at 1:30 and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Antigen-bound antibodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig H+L antibody (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) at 1 ng/ml with incubation for 1 h at 37°C. The tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc.) was added, and the reaction was stopped after 10 min by addition of 1 M phosphoric acid. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm with an ELISA plate reader (Dynex; MRX Revelation). The results were expressed as endpoint antibody titers calculated by regression analysis, plotting dilution versus the A450 [regression curve: y = (b + cx)/(1 + ax)]. Endpoint titers were calculated as the highest dilution giving twice the absorbance of the negative control.

RESULTS

Sequence analysis and secondary structure of the PA linker (linking the endonuclease to the PB1 binding domain).

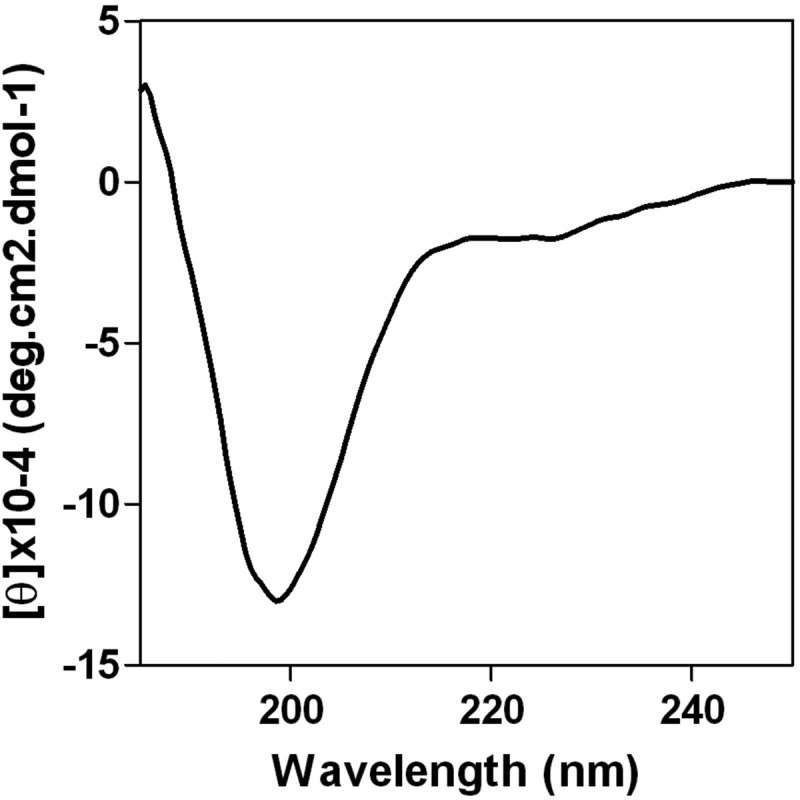

With a length of 58 to 60 residues, the PA linker possesses 12 residues conserved among influenza A, B, and C viruses (Fig. 1A, in bold), mainly located between positions 210 and 232 and including charged and hydrophobic residues. This domain has an identical structure in the influenza A and B virus polymerases (11, 17). To investigate its structure in the absence of other viral components, the PA linker of the H1N1 A/WSN/33 (WSN) virus was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified to homogeneity. Its secondary structure was estimated using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. The recorded spectra showed shape characteristics of a random coiled conformation with no evidence of stable secondary structures (Fig. 2). Dynamic light scattering analyses showed that the PA linker has a hydrodynamic radius of about 3 nm, suggesting that it exists as a monomer in solution. These data suggest that the PA linker mainly adopts a disordered structure when not associated with other polymerase components and that its conserved residues among influenza A, B, and C viruses are not the mark of intramolecular stable self-folding.

FIG 2.

Secondary structure of the PA linker. The far-UV CD spectrum was recorded in 20 mM sodium acetate, pH 6.

Generation of PA mutant viruses.

For mutagenesis in the PA linker, we selected amino acids that are conserved among influenza A, B, and C virus sequences as well as amino acids located in close proximity to these residues. In total, 19 amino acid positions were selected for analyses. Two types of substitutions were engineered: residues replaced by a Pro residue, to disturb potential structuration of this domain, and an Ala residue, because of its nonbulky, chemically inert methyl functional group. Since the X ORF overlaps the linker reading frame, several substitutions engineered in the linker were nonsilent in the X ORF (Table 1). In these cases, to determine if the phenotype we observed was due to a mutation in the linker or in the X ORF, we included modifications in the frameshift motif from UUU CGU (codons 191 and 192) to UUC AGA to reduce frameshifting and the resulting expression of PA X (as reported previously in reference 21). Using plasmid-driven reverse genetics, we were able to generate 31 virus mutants with Pro or Ala substitutions, with or without modifications in the frameshift motif (Table 2). Four mutations (L214P, S218P, P220A, and E237P) did not allow virus recovery, suggesting that they severely impaired PA structure and/or function.

TABLE 1.

Components of virus rescue experiments

| Mutant PA/PA X | Rescue/ts phenotype | Oligonucleotidea |

|---|---|---|

| T210A/− | + | GATTTGAAATCACAGGAGCAATGCGCAAGCTTGCCG |

| T210P/E209D | +/ts | GATTTGAAATCACAGGACCAATGCGCAAGCTTGCCG |

| T210P/E209D+FS | +/ts | GATTTGAAATCACAGGACCAATGCGCAAGCTTGCCG |

| K213A/S213R | + | CACAGGAACAATGCGCGCGCTTGCCGACCAAAGTC |

| K213P/S213R | +/ts | CACAGGAACAATGCGCCCGCTTGCCGACCAAAGTC |

| L214A/S213R | + | CAGGAACAATGCGCAAGGCTGCCGACCAAAGTCTCCC |

| L214P/− | − | CAGGAACAATGCGCAAGCCTGCCGACCAAAGTCTCCC |

| D216A/T216P | + | CAATGCGCAAGCTTGCCGCCCAAAGTCTCCCGCCAAAC |

| D216P/T216P | +/ts | CAATGCGCAAGCTTGCCCCCCAAAGTCTCCCGCCAAAC |

| D216P/T216P+FS | +/ts | CAATGCGCAAGCTTGCCCCCCAAAGTCTCCCGCCAAAC |

| Q217A/K217Q | + | CAATGCGCAAGCTTGCCGACGCAAGTCTCCCGCCAAACTTC |

| Q217P/K217P | + | CAATGCGCAAGCTTGCCGACCCCAGTCTCCCGCCAAACTTC |

| S218P/V218L | − | CGCAAGCTTGCCGACCAACCTCTCCCGCCAAACTTC |

| L219A/S219P | +/ts | CAAGCTTGCCGACCAAAGTGCCCCGCCAAACTTCTCCAGCC |

| L219P/S219L | +/ts | CAAGCTTGCCGACCAAAGTCCTCCGCCAAACTTCTCCAGCC |

| P220A/− | + | GCTTGCCGACCAAAGTCTCGCGCCAAACTTCTCCAGCC |

| P221A/Q221L | +/ts | CCGACCAAAGTCTCCCGGCTAACTTCTCCAGCCTTG |

| N222A/T222P | + | GACCAAAGTCTCCCGCCAGCCTTCTCCAGCCTTG |

| N222P/Q221H,T222P | +/ts | GACCAAAGTCTCCCGCCACCCTTCTCCAGCCTTG |

| F223A/S223P | + | CCAAAGTCTCCCGCCAAACGCCTCCAGCCTTGAAAATTTTAG |

| F223P/S223P | +/ts | CCAAAGTCTCCCGCCAAACCCCTCCAGCCTTGAAAATTTTAG |

| S224P/ | + | GTCTCCCGCCAAACTTCCCTAGCCTTGAAAATTTTAG |

| S225P/ | +/ts | CTCCCGCCAAACTTCTCCCCCCTTGAAAATTTTAGAGC |

| L226A/− | + | GCCAAACTTCTCCAGCGCTGAAAATTTTAGAGCC |

| L226P/− | +/ts | GCCAAACTTCTCCAGCCCTGAAAATTTTAGAGCC |

| E227A/K227Q | + | CCAAACTTCTCCAGCCTTGCAAATTTTAGAGCCTATG |

| E227P/L226F,K227Q | + | CCAAACTTCTCCAGCCTTCCAAATTTTAGAGCCTATG |

| E237A/N237P | + | GCCTATGTGGATGGATTCGCCCCGAACGGCTACATTGAG |

| E237P/N237H | − | GCCTATGTGGATGGATTCCCACCGAACGGCTACATTGAG |

Underlined portions of sequences indicate the substituted nucleotides, and portions shown in italics indicate the sequence of the PA mutated codon.

TABLE 2.

Summary of phenotypes induced by mutations in the PA hinge

| Rescue virus | Phenotypea | Virus titer (PFU/ml) atb: |

Replication kinetics phenotypec | Polymerase activity atd: |

Revertant selection and isolation | Nuclear import of PB1 ate: |

Pathogenicityf | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33°C | 37°C | 39.5°C | 33°C | 39.5°C | 33°C | 39.5°C | |||||

| PA wt | + | 1.7 ′ 108 | 4.8 ′ 108 | 1.3 ′ 108 | wt | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | 3.5 | |

| PA wt FS | + | 9.5 ′ 107 | 4.8 ′ 107 | wt | |||||||

| E198P | − | − | |||||||||

| E198A | + | + | |||||||||

| I201P | − | − | |||||||||

| I201A | ++ | + | |||||||||

| T210P | +/ts | 3.8 ′ 108 | 1.6 ′ 108 | 5 ′ 107 sp | ts++ | ++ | − | + | |||

| T210P FS | +/ts | 2.4 ′ 107 | 4.0 ′ 105 | ts+++ | |||||||

| T210A | + | +++ | + | ||||||||

| K213P | +/ts | 6 ′ 108 | 5 ′ 108 | 107 sp | ts+ | +++ | − | ||||

| K213A | + | +++ | +++ | ||||||||

| L214P | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | − | +/− | − | |||

| L214A | + | − | − | ||||||||

| D216P | +/ts | 4.4 ′ 108 | 5 ′ 107 | <103 | ts+++ | + | − | + | ++ | +/− | 5.5 |

| D216P FS | +/ts | 1.0 ′ 108 | 2.4 ′ 105 | ts+++ | |||||||

| D216A | + | +++ | + | ||||||||

| Q217P | + | ||||||||||

| Q217A | + | ||||||||||

| S218P | − | − | − | ||||||||

| S218A | +++ | ++ | |||||||||

| L219P | +/ts | 4 ′ 108 sp | 4 ′ 108 sp | 1.2 ′ 104 sp | ts+++ | − | − | + | ++ | +/− | >6 |

| L219A | +/ts | ||||||||||

| P220A | − | − | − | ||||||||

| P221A | +/ts | ||||||||||

| N222P | +/ts | ||||||||||

| N222A | + | ||||||||||

| F223P | +/ts | 6 ′ 108 | 8 ′ 107 | <103 | ts+++ | + | − | + | ++ | − | |

| F223A | + | +++ | + | ||||||||

| S224P | + | ||||||||||

| S225P | +/ts | ||||||||||

| L226P | +/ts | 6 ′ 108 | 1.6 ′ 108 | 1.2 ′ 105 | ts+ | + | − | ||||

| L226A | + | +++ | − | ||||||||

| E227P | + | 5 ′ 108 | 4 ′ 108 | 1.2 ′ 108 sp | wt | ++ | ++ | ||||

| E227A | + | +++ | ++ | ||||||||

| Y232P | − | − | |||||||||

| Y232A | +++ | + | |||||||||

| E237P | − | ||||||||||

| E237A | + | ||||||||||

| M249P | − | − | |||||||||

| M249A | + | − | |||||||||

| T210P + D216P | +/ts | 5.0 ′ 107 | 2.0 ′ 105 | ts++ | |||||||

+, the virus demonstrated efficient rescue; -, efficient rescue did not occur; ts, the virus had the temperature-sensitive phenotype.

Titers followed by the notation “sp” signify low titers.

Replication kinetics symbols: ts+++, no virus amplification at 39.5°C; ts++, a latency phase was observed at 39.5°C; ts+, a delay in virus replication compared to that of the wild-type virus was observed.

+++, 50 to 100% of the wild-type polymerase activity; ++, 30 to 50% of the wild-type activity; +, 5 to 30% of the wild-type activity; -, 0 to 5% of the wild-type activity.

Symbols for nuclear import of PB1: +++, >80% of the cells were exclusively labelled in the nucleus; ++, between 50% and 80% of the cells were exclusively labelled in the nucleus; +/−, between 30% and 0% of the cells were exclusively labelled in the nucleus; −, no labelled nucleus.

Pathogenicity was quantified based on the LD50 (expressed in log PFU).

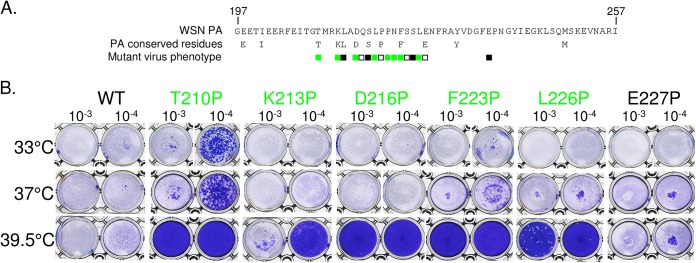

Temperature sensitivity of viruses with a mutated PA.

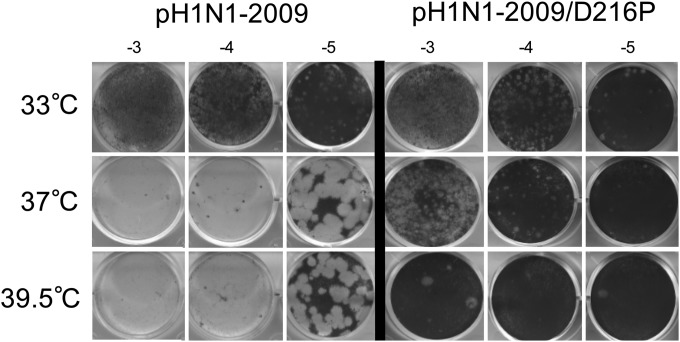

We next examined the replicative abilities of the mutant viruses in cell culture. MDCK cells were infected with serial dilutions of wild-type WSN or PA mutant viruses and incubated at 33°C, 37°C, and 39.5°C for plaque assays. Based on their replicative capacities, the PA mutants could be divided into two groups. As exemplified in Fig. 3 for some of them and as summarized in Table 2, several mutants (T210P, K213P, D216P, L219P, L219A, P221A, N222P, F223P, S225P, and L226P) exhibited a temperature-sensitive phenotype. While these mutants lysed monolayers with the same efficiency as WSN at 33°C and 37°C, they were not (or were only poorly) able to form plaques at 39.5°C, unlike WSN. Only a few other mutants (as shown for E227P in Fig. 3) lysed monolayers with the same efficiency as the parental virus at 33°C, 37°C, and 39.5°C. Note that all the identified ts mutants harbored a Pro substitution, and never an Ala substitution, with the notable exceptions of the P221A and L219A mutants (the latter showed a less pronounced ts phenotype than the L219P mutant, however). It should also be mentioned that the introduction of a silent mutation at codon position 191 to reduce the frameshift efficiency in generation of PA X did not alter the ts phenotype induced by the mutations T210P and D216P, showing that this phenotype is attributable to the modification of the PA reading frame and not the PA X reading frame.

FIG 3.

Virus recovery and phenotypes of mutants generated in the PA linker domain. (A) The amino acid sequence of the PA linker domain and the conserved residues among influenza A, B, and C viruses are indicated in single-letter codes. Positions that were chosen for the analysis are indicated by squares. Amino acids were replaced with a proline (or an alanine for the P220 and P221 positions), and mutants were recovered via reverse genetics. Substitutions that were found to confer a ts phenotype are labeled in green. White squares indicate efficient virus rescue without the ts phenotype. Black squares indicate no detectable rescued virus. (B) Results of the plaque assay used to characterize temperature sensitivity and for selection of mutants.

To determine whether two ts mutations in the PA linker can be combined to produce a more exacerbated phenotype, we engineered two additional mutants containing both the ts mutations T210P and D216P, with or without the nucleotide mutation that inhibits the frameshift efficiency at codon 191. These mutants were viable and both exhibited a marked ts phenotype (Table 2).

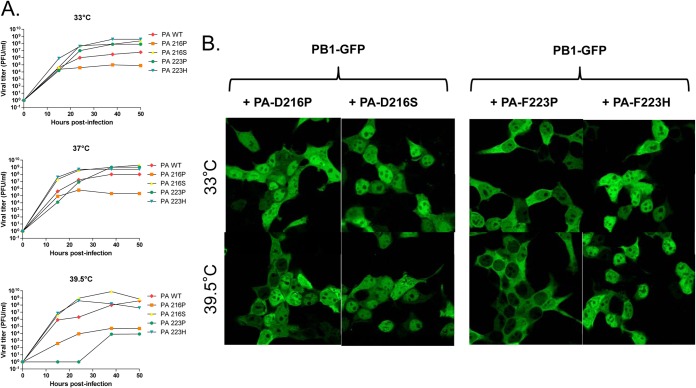

To determine if the ts phenotype of the mutants can be expressed in another virus backbone, we used a reverse genetics system for the H1N1pdm09 virus (described previously in reference 36). The D216P and L219P mutations were introduced into the H1N1pdm09 PA gene. A mutant virus was rescued for the D216P mutation, but not for the L219P mutation. The D216P mutation displayed a ts phenotype in the H1N1pdm09 backbone, similar to the one observed in the WSN backbone, showing that the ts phenotype can be conferred to a virus currently circulating in humans (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

H1N1pdm09 D216P virus phenotype. Serial dilutions (103 to 105) of the wild type of the D216P mutant H1N1pdm09 virus were used to infect MDCK monolayers at the indicated temperatures, and a plaque assay was performed. The D216P mutant exhibited a ts phenotype.

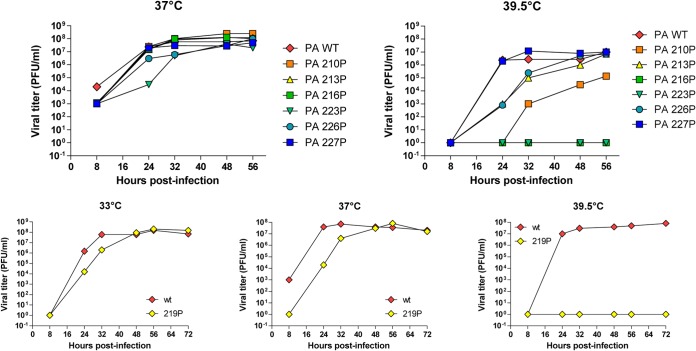

To further characterize the temperature sensitivity of the recombinant mutants, infections of MDCK cells at a low MOI of 0.01 PFU/cell were carried out at 33°C, 37°C, and 39.5°C, and virus progeny production was quantified at different times postinfection (Fig. 5 and Table 2). Figure 5 (upper panels) shows that the D216P and F223P mutants showed no detectable replication at 39.5°C, while they were able to replicate efficiently at 37°C. The mutants T210P, K213P, and L226P exhibited a less pronounced phenotype, with similar production kinetics at 37°C compared to the wild-type virus and partial defects in replication efficiency at 39.5°C: virus amplification was delayed, and final virus titers at 56 h postinfection (p.i.) were between 105 and 107 PFU/ml, compared to 107 PFU/ml for the wild type. The mutant E227P, which did not display a ts phenotype in our previous assays (Fig. 3), showed similar replication kinetics as the wild-type virus at 37°C and 39.5°C (Fig. 5, upper panels). Finally, compared to the wild-type virus, the L219P mutant showed no detectable multiplication at 39°5C and a delay in virus production at 37°C and 33°C (Fig. 5, lower panels), suggesting that this mutation has a more deleterious effect than the other ts mutations on virus replication. Overall, these data indicate that single substitutions in a small subdomain of the PA linker, mapping from positions 210 to 226, allow generation of mutants that display strong or less-pronounced ts phenotypes.

FIG 5.

Kinetics of replication of the mutant viruses at different temperatures (33°C, 37°C, and 39.5°C) upon seeding on MDCK cells at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01. Titers were determined via plaque assays on MDCK cells.

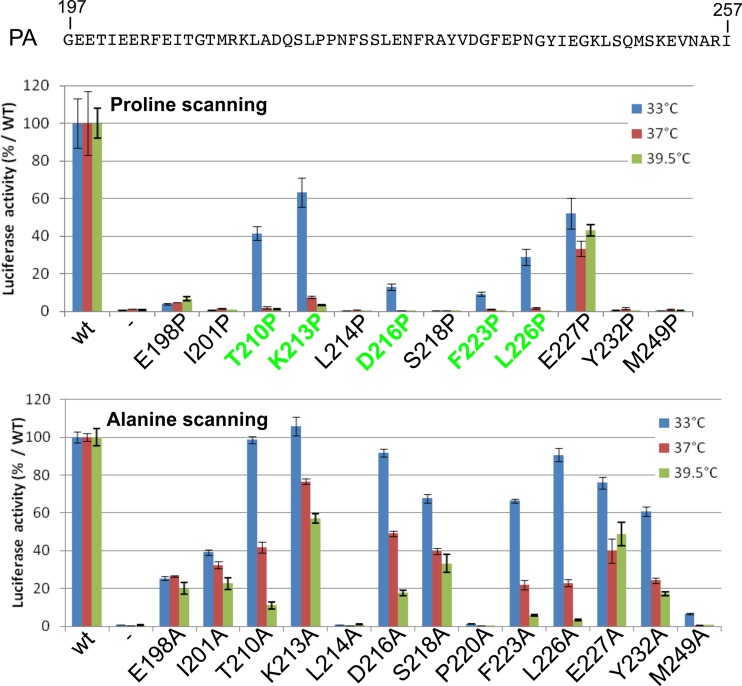

Polymerase activities of replication complexes containing PA mutations.

We assessed the effects of PA linker mutations on the replication/transcription activity of the viral polymerase, using a minireplicon assay. The pPol1-WSN-NA-firefly luciferase plasmid produces a modified influenza virus NA viral RNA (vRNA) in which the NA coding sequences are replaced by the firefly luciferase gene. Upon cotransfection of HEK-293T cells with the pPol1-WSN-NA-firefly luciferase plasmid together with plasmids allowing expression of PB1, PB2, NP, and PA (wild-type or mutant PA), the luciferase enzymatic activity measured in cell extracts reflects the overall transcription and replication activities of the transiently expressed viral polymerase. We first observed that the wild-type polymerase activity was higher at 37°C than at 33°C (with an about 4-fold increase) and 39.5°C (2-fold). Compared to the wild type at a given temperature, all the polymerases reconstituted with a mutant PA had a reduced activity, a feature that was generally less pronounced at 33°C than at 37°C and 39.5°C (Fig. 6 and Table 2). Importantly, mutations T210P, K213P, D216P, F223P, and L226P, which induced a ts phenotype in the context of an infectious virus, also promoted a ts phenotype in the minireplicon assay, with a polymerase activity at 33°C ranging from 7 to 61% of the wild-type activity and less than 2% of the wild-type activity at 39.5°C (and even at 37°C). The mutants L214P, L214A, S218P, and P220A (as well as L219P and S225P [data not shown]) showed no or very low luciferase activity at 33°C, 37°C, and 39.5°C; viruses harboring these mutations were not rescued, with two notable exceptions, the L219P and the P220A mutants. Furthermore, Pro substitutions always have more drastic effects on the replication/transcription machinery than Ala mutations, suggesting that the PA linker may acquire a defined and adequate conformation during the replication process. In contrast to all other PA Pro mutants, the PA E227P mutant exhibited similar and efficient activities at 33°C, 37°C, and 39.5°C, in accordance with the absence of temperature sensitivity of the corresponding mutant virus. To verify that the decrease of PA mutant activities at the restrictive temperature was not due to protein degradation, a Western blot analysis was carried out on transfected cells. No PA mutant degradation was detected in the assay (data not shown). These results taken as a whole suggest that the temperature sensitivity of the mutants is associated with a defect in the replication/transcription activity of the polymerase or an earlier step of the virus cycle. Two additional points should be noted: (i) the drop of polymerase activity for the ts mutations was observed at 37°C (and 39.5°C), not only at 39.5°C, while the ts phenotype of the virus mutants was only identified at 39.5°C (and not at 37°C), suggesting that the minigenome test is more sensitive and/or does not strictly mimic the viral RNA polymerase activities in infected cells as previously observed (37); (ii) additional proline substitutions engineered at the extremities of the linker and at conserved positions between influenza A, B, and C viruses (E198, I201, Y232, and M249) were all deleterious for the polymerase activity and did not reveal additional mutations able to confer a ts phenotype in this assay.

FIG 6.

Transcription/replication activity of the polymerase complex with wild type or PA mutants. Plasmids expressing NP, PB1, PB2, and wild type or PA mutants were cotransfected in 293T cells together with the reporter plasmid WSN-NA-firefly luciferase, allowing the quantification of the polymerase activity at different temperatures (33°C, 37°C, and 39.5°C). A plasmid harboring the β-galactosidase (pRSV-β-Gal) gene was cotransfected to control DNA uptake. Luciferase activity was measured in cell lysates 48 h posttransfection. Data are expressed as the mean luciferase activity ± the standard error of the mean of three replicates normalized to β-galactosidase activity. (Upper panel) Amino acids replaced with a proline; (lower panel) amino acids replaced with an alanine.

PA ts (and lethal) mutations block the recruitment and the transport of PB1 toward the nucleus at nonpermissive temperature.

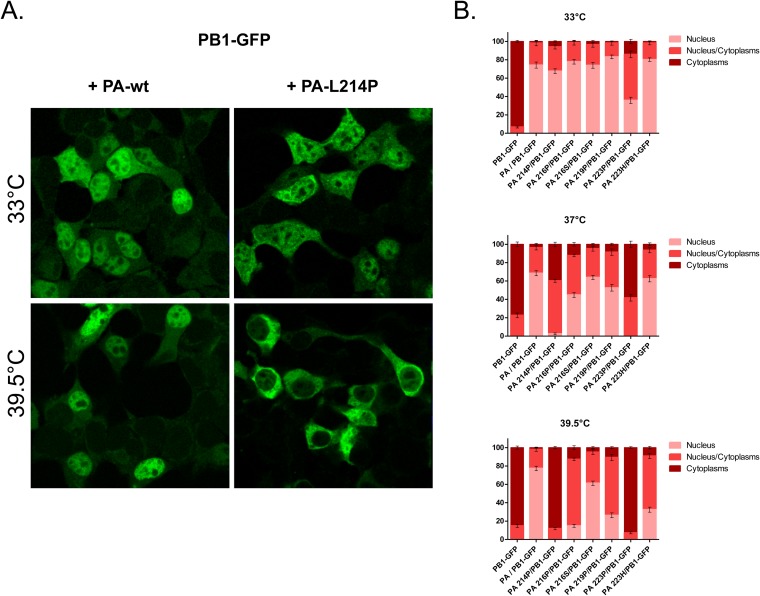

The inefficient polymerase activity of the PA mutants at nonpermissive temperature could result from a defect in the genome transcription/replication process or in any upstream step, such as the assembly of the polymerase subunits or the import of the polymerase subunits in the nucleus. In order to determine whether the ts mutations may interfere with the nuclear import of PA or the formation of the PA-PB1 complex in the cytoplasm and its transport to the nucleus, we generated a series of plasmid constructs to express or coexpress the PA and PB1 subunits. Fluorescently labeled PB1 and PA (wild-type and mutant) subunits were first expressed separately to study their intracellular localization (data not shown). Both types of subunits showed an accumulation in the cytoplasm and a faint localization in the nucleus, in accordance with previous data (5, 6, 7). The cytoplasmic localization of PA was more pronounced than observed in previous studies, possibly reflecting the use of different cell lines or perhaps due to differences in the PA sequences.

Next, we analyzed the localization of the PB1 subunit when coexpressed with PA (Fig. 7; Table 2). Our experiments confirmed that when the wild-type PA and PB1 were expressed together, PB1 and PA localized into the nucleus, in contrast to what was observed when PB1 or PA was expressed alone. The temperature used during protein expression (33°C, 37°C, or 39.5°C) did not modulate the PB1 targeting to the nucleus: about 80% of the PB1-expressing cells were labeled in the nucleus at any temperature (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

Subcellular localization of the influenza virus polymerase PB1 subunit transiently expressed in 293T cells with PA mutants. (A) Subcellular localization of a PB1-GFP fusion protein when coexpressed with wild type or L214P PA at 33°C and 39.5°C. (B) Percentage of PB1-GFP-expressing cells with nuclear versus cytoplasmic localization of PB1-GFP. PB1-GFP was expressed alone or with different forms of PA: wild type, mutant forms L214P, D219P, and F223P, or revertant forms P216S and P223H (see Fig. 8 for additional data on PA revertant forms). The means and standard deviations from three experiments are shown, in each of which a mean of 200 cells were scored for each condition.

We next coexpressed PB1 with either one of the following PA mutants: L214P, which did not allow rescue, or D216P, L219P, or F223P (Fig. 7). At 33°C, the PA mutants were able to recruit PB1 into the nucleus, with the notable exception of F223P, which did not allow PB1 to reach the nucleus efficiently. At 37°C, transport of PB1 to the nucleus was strongly inhibited by PA mutants L214P and F223P. A less drastic effect was observed with mutants D216P and L219P. At 39.5°C, all PA mutants displayed a strong defect in their ability to promote PB1 transport to the nucleus (as illustrated in Fig. 7A for L214P and quantified in Fig. 7B). We noted that the viable ts mutation F223P conferred a more pronounced effect on PB1 transport to the nucleus than the lethal mutation L214P at any temperature. The default in the efficient PB1 migration at 39.5°C toward the nucleus was correlated with the absence of PA mutants in the nucleus (data not shown).

These results showed that the transport of PB1 to the nucleus when coexpressed with one of the PA mutants is temperature dependent, suggesting that the inability of PA mutants to recruit PB1 to target the nucleus is associated with the ts phenotype of the corresponding mutant viruses.

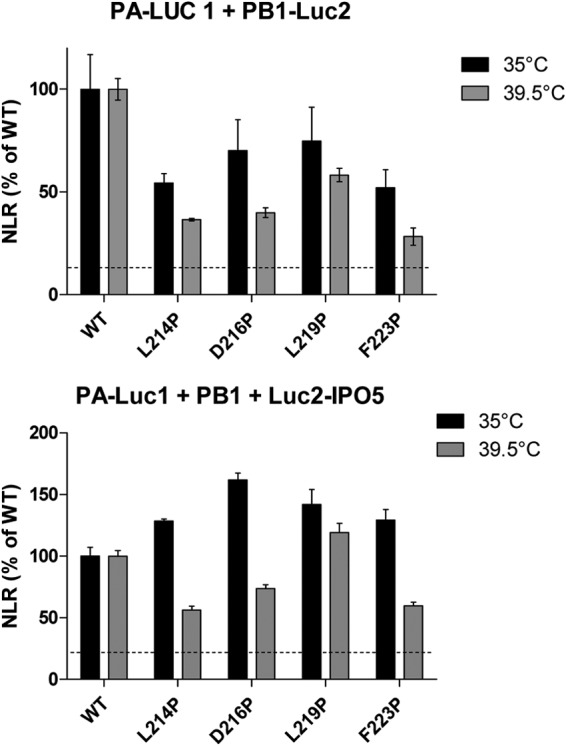

PA ts (and lethal) mutations modulate the interaction between PA and PB1 and with the importin IPO5 (formerly named RanBP5).

The deficiency of PA-PB1 targeting the nucleus at nonpermissive temperatures may be due to instability of the PA-PB1 complex and/or to inefficient binding to the β-importin IPO5, previously shown to be involved in the nuclear import of the PA-PB1 complex (29, 38). To investigate these hypotheses, we used a Gaussia princeps luciferase-based complementation assay (33, 34) to quantify the binding of PA mutants to PB1 at permissive (35°C) and nonpermissive (39.5°C) temperatures. Figure 8 shows that all the mutations tested (L214P, D216P, L219P, and F223P) impaired the binding with PB1 at both temperatures and that this defect was more pronounced at 39.5°C than at 35°C. For instance, compared to the PA wild-type form, the D216P PA mutant binds to PB1 with an efficiency of 70% at 35°C and 40% at 39.5°C. These results suggest that PA-PB1 complex formation might be a limiting factor for nuclear import of the complex at nonpermissive temperature. We next quantified the binding of the PA-PB1 complex to IPO5 at permissive and nonpermissive temperatures. To this end, we coexpressed the PA-Gluc1 and Gluc2-IPO5 fusion proteins together with PB1. In agreement with previous data showing that PB1, but not PA, binds to IPO5 (38), no interaction signal between PA and IPO5 was detected in the absence of coexpressed PB1 (data not shown). Thus, our assay was able to detect specifically the association of the PA-PB1 complex with IPO5. Compared to the wild type, all four tested PA mutants were less efficient at forming a PA-PB1-IPO5 complex at 39.5°C than at 35°C, whereas all the PA mutants, including F223P, formed a complex with PB1 and IPO5 at 35°C. Overall, our results suggest that PA-PB1 complex formation and its association with IPO5 are key determinants in the phenotype of the ts mutants. Distinct determinants probably underlie the disruption of the F223P mutant's ability to promote translocation of PB1 in the nucleus at 33°C.

FIG 8.

Normalized luminescence ratios as determined in a split Gaussia luciferase-based complementation assay for the indicated protein complexes and at the indicated temperature. (A) Wild-type or mutant PA proteins fused to Gluc1 were coexpressed with PB1-Gluc2. (B) Wild-type or mutant PA proteins fused to Gluc1 were coexpressed with PB1 and with an IPO5-Gluc2 fusion protein. Luciferase activity was measured in cell lysates 24 h posttransfection. Data are expressed as the mean luciferase activity ± the standard error of the mean of triplicates.

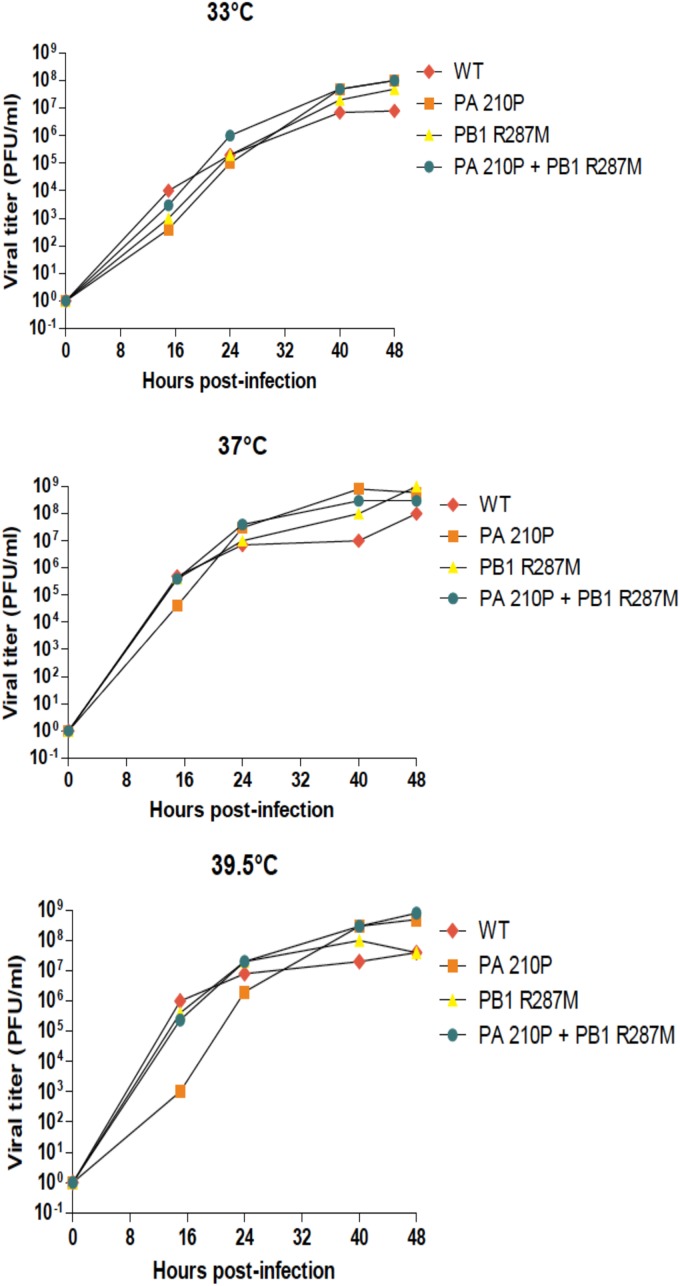

Production and analysis of phenotypic revertants.

In order to evaluate the genetic stability of the ts mutations and to identify possible functional links between the different polymerase subunits, we aimed at selecting revertants for several ts viruses. Revertants for the ts phenotype were selected by serial passages of the ts mutants at 39.5°C followed by plaque purification. Table 3 lists the revertants that were selected and the mutations that were identified by nucleotide sequencing. Different types of revertants were obtained: (i) several had reversions at the residue that was initially mutated, like ts210P/Rev1, ts216/Rev2, and ts223P/Rev1, in which the Pro codon was mutated to produce a Thr, a Ser, and a His, respectively; (ii) several had intragenic mutations, like ts210/Rev2 with the PA E377K substitution; (iii) several had extragenic mutations, like ts210/Rev5 and ts210/Rev6, with the mutations R136G and R287M in the PB2 and PB1 subunits, respectively. To determine whether the mutations identified in the revertants were indeed responsible for the reversion of the ts phenotype, substitutions were engineered in the wild-type/parental (WSN) and the ts backbones for further analysis. A replication kinetic study of the T210P mutant in comparison to the engineered revertant that possesses the T210P and the PB1 R287M substitutions was carried out. A mutant virus carrying only the PB1R287M substitution was also produced. Replication of the T210P mutant was delayed at 39.5°C compared to the wild type and the double mutant T210P-PB1R287M (Fig. 9). Similar growth kinetics were observed with all these viruses at 33°C and 37°C. It should be noted that the size of the plaques formed by the PB1R287M mutant were found statistically larger than the wild-type plaques (data not shown), suggesting a dominant effect of this substitution. To determine if the reversions were able to restore the ability of PA to recruit and target PB1 to the nucleus, the PA revertants ts216/Rev2 (PA-P216S) and ts223/Rev1 (PA-P223H) were analyzed. First, infections of MDCK cells at a low MOI (0.01) were carried out at 33°C, 37°C, and 39.5°C, and virus progeny production was quantified at different times postinfection (Fig. 10A). As a main feature, while the D216P and F223P ts mutants replicated poorly at 39.5°C, their revertants P216S and P223H replicated as efficiently as the wt virus. Next, the two revertant PA proteins were coexpressed with PB1-GFP. Figure 10B (and Fig. 6B for quantification data) shows that the two revertant proteins were able to target PB1 to the nucleus at the nonpermissive temperature (39.5°C), in contrast to the ts mutant proteins D216P and L223P. These results confirm the critical importance of the PA linker in the recruitment of PB1 for nuclear import.

TABLE 3.

Revertant descriptions

| ts mutation | Revertant | Substitution(s) identified in the revertant | Nucleotide sequencea |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA T210P | ts210/Rev1 | PA P210T | GGA ACA ATG/GGA ACA ATG |

| ts210/Rev2 | PA E377K | CCA AAA AAG/CCA GAA AAG | |

| ts210/Rev3 | PA A432V + PB1 R287M | GAT GTG GCT/GAT GCG GCT | |

| GTA ATG AAG/GTA AGG AAG | |||

| ts210/Rev4 | PA A20T | AAG ACA ATG/AAG GCA ATG | |

| ts210/Rev5 | PB2 R136G + PB2 D309N | TTT GGA AAC/TTT AGA AAC | |

| GTG AAT ATT/GTG GAT ATT | |||

| PA D216P | ts210/Rev6 | PB1 R287M | GTA ATG AAG/GTA AGG AAG |

| ts216/Rev1 | PA P216D | GCC GAC CAA/GCC GAC CAA | |

| ts216/Rev2 | PA P216S | GCC TCC CAA/GCC GAC CAA | |

| PA L219P | ts219/Rev1 | PA P219L | AGT CTT CCG/AGT CTC CCG |

| ts219/Rev2 | PA P219L + PA A20T | AGT CTT CCG/AGT CTC CCG | |

| AAG ACA ATG/AAG GCA ATG | |||

| PA F223P | ts223/Rev1 | PA P223H | AAC CAC TCC/AAC TTC TCC |

Nucleotide sequences for the revertant and wild-type sequences (the two sequence types are divided by a slash; the mutated codons are surrounded by −1 and +1 codons).

FIG 9.

Kinetics of replication of the mutant viruses PA T210P, PB1 R287M, and PA T210P plus PB1 R287M at different temperatures (33°C, 37°C, and 39.5°C) upon seeding on MDCK cells at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01. Titers were determined by plaque assays on MDCK cells.

FIG 10.

Characterization of reverse mutations. (A) Kinetics of replication of the mutant viruses D216P and F223P and their revertants P216S and P223H at different temperatures (33°C, 37°C, and 39.5°C) upon seeding on MDCK cells at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01. Titers were determined by plaque assays on MDCK cells. (B) Subcellular localization of the PB1-GFP fusion protein coexpressed with PA reverse mutants D216S and F223H at permissive (33°C) and nonpermissive (39.5°C) temperatures.

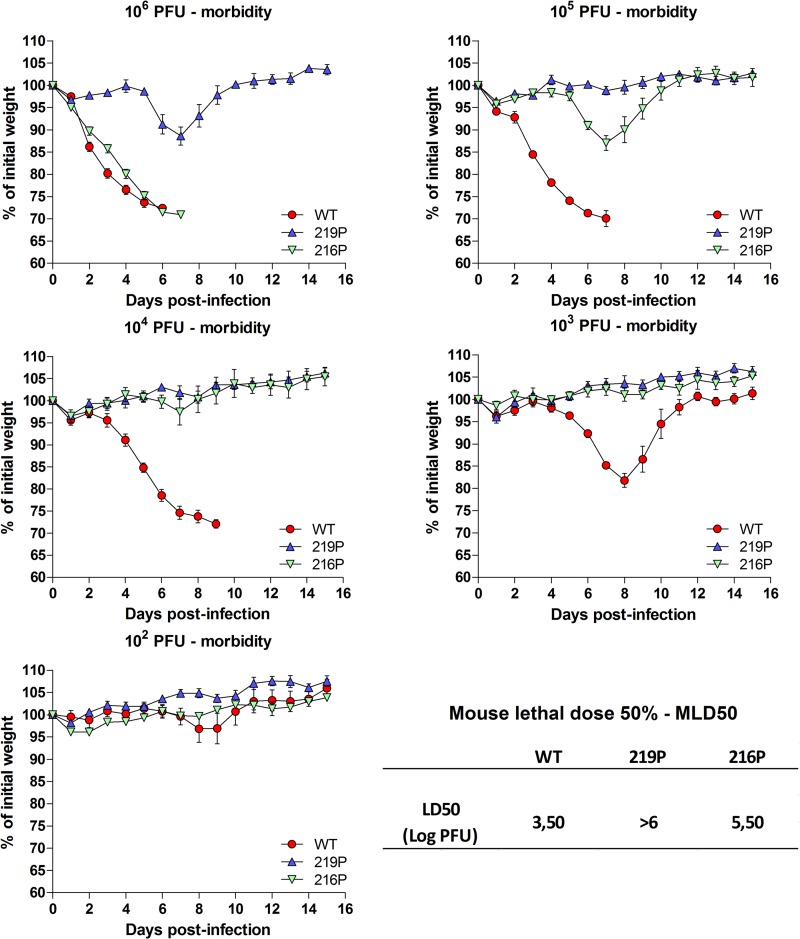

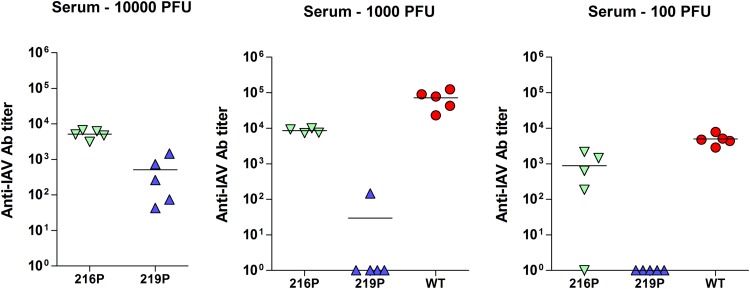

Pathogenicity of PA mutant viruses and host antibody response.

To investigate the effects of the ts mutations in vivo, we infected groups of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) intranasally at different infectious doses of the two mutants, D216P and L219P, or the parental WSN virus, to measure and compare mortalities and LD50s, morbidities, and antibody responses. In response to a high viral challenge (1 × 106 PFU), while the two groups of mice (wt- and D216P-infected mice) were as sensitive (0% survival for both groups) and lost weight at the same rate, none of the L219P-infected mice died; they lost 12% of weight at day 7 p.i. to recover later (Fig. 11; Table 2). When infections were carried out with lower doses of viruses (1 × 105 and 1 × 104 PFU), while wt-infected mice died, D216P- and L219P-infected mice all recovered. No loss of weight was observed with mice infected with the L219P mutant at these two infectious doses. At the 1 × 103 dose, only wt-infected mice still exhibited loss of weight (18%). No weight decrease was observed when mice were inoculated with 1 × 102 PFU of the three viruses. The LD50s were estimated to be 3.50 log PFU with the wt virus, >6 log PFU for the L219P mutant, and 5.50 log PFU with the D216P mutant. To determine whether infections with the mutants elicited an immune adaptive response, we assessed antibody responses in the mice surviving to the different challenges 2 weeks p.i. Measurement of antibody was carried out to evaluate the potential of these mutants to act as efficient live vaccines. As shown in Fig. 12, with an infectious dose of 102 or 103 PFU, both D216P and wt viruses, but not the L219P mutant, induced a strong antibody response, suggesting that the temperature sensitivity of the L219P mutant is too marked to allow replication and induction of an efficient immune response. At 104 PFU, the L219P mutant was able to induce antibody synthesis.

FIG 11.

Morbidity induced by WSN and the two temperature-sensitive D216P and L219P mutants. Mice (n = 10) received intranasally 10-fold dilutions of viruses (from 106 to 102 PFU/mouse) and were weighed daily. Mice with a weight loss of 25% were considered dead and euthanized. The LD50 was estimated to be 3.5 (on a log PFU scale) for the wt, >6 for L219P, and 5.5 for D216P.

FIG 12.

Anti-influenza virus antibody titers induced by infection with PA mutant viruses. The antibody titers were measured 2 weeks postinfection via conventional ELISAs.

These results indicate that the two ts mutants D216P and L219P are both strongly attenuated yet nevertheless able to induce an efficient antibody response.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that the PA linker defined by the stretch of amino acids 197 to 257 is associated with a key function in the virus cycle. ts and lethal mutations engineered in this domain displayed a particular phenotype: these mutations were associated with a defect in the formation of the PA-PB1 complex and in its import into the nucleus at a nonpermissive temperature.

The recent elucidation of the crystal structures of the RNA polymerase from an influenza B virus and an unconventional bat influenza virus (H17N10), as well as the cryo-electron microscopy structure of an H5N1 polymerase complex at 4.3 Å resolution, shed light on the PA-linker mutant properties (11, 17, 39). The two structurally known domain of PA, the PA-Nter endonuclease domain (residues 1 to 196) and the large PA-C domain (residues 258 to 714) are on opposite sides of the molecule, connected by the PA linker, which wraps around the external face of PB1 fingers and palm domain. The PA linker, which includes three helical segments at positions 209 to 218, 226 to 234, and 241 to 248, lie across the surface of PB1, making numerous, often-conserved intersubunit contacts that are both hydrophobic and polar in nature (Fig. 1C). The lethal substitutions (L214P, S218P, and P220A) map to conserved (among influenza A, B, and C viruses) residues in close contact with PB1 residues. In contrast, positions defined by ts mutations present in the helical segment (positions 210, 213, and 216 within the segment from residues 209 to 218) are not strongly (or directly) involved in interactions with PB1. Substitutions with a strong ts phenotype (L219P and F223P) are clustered in a hairpin marked by two prolines at positions 220 and 221 between helices formed by residues 209 to 218 and residues 226 to 234. Furthermore, we observed that ts or lethal mutations were generally associated with substitutions of conserved residues (T210P, K213P, L214P, D216P, S218P, P220A, and F223P), but ts mutants were also identified with substitutions of nonconserved residues (P221A, N222P, S225P, and L226P). Substitutions for proline were systematically found to alter more drastically the polymerase activity and virus viability than did alanine substitutions. This observation is in accordance with the fact that ts or lethal substitutions were all found in helices interacting with PB1 residues or in the structured turn (residues 219 to 225), which are likely to be altered by a proline substitution. However, we noticed that a substitution breaking the helix at positions 226 to 234 did not necessary result in a ts phenotype: the E227P substitution did not produce the ts phenotype, whereas a substitution at the adjacent hydrophobic residue (L226P) did produce the ts phenotype. Taking these observations as a whole, we conclude that hydrophobic PA residues interacting with PB1 in the helices of residues 209 to 218 and residues 226 to 234 and in the turn at residues 219 to 225 play a key role in the function of the polymerase complex and that some of them are potential targets with regard to generation of a ts phenotype. The fact that the PA linker is not structured on its own shows that it acquires its structure during the assembly of the PA-PB1 complex and suggests that it may participate in the stabilization of the PA-PB1 heterodimer.

An unanticipated finding was the high number of ts mutants we generated in the PA linker. Until now, only a few ts mutations were identified in the influenza virus polymerase locus, and they did not group together in such a cluster. They were mainly found at distant positions in the PB1 (3 mutations at positions 391, 581, and 661) and PB2 (4 mutations at positions 265, 112, 556, and 658) subunits (24, 25, 26). Furthermore, in contrast to what we observed with PA linker single substitutions, ts phenotypes often result from the simultaneous presence of several mutations at these positions. For instance, the ts phenotype of the A/AA/6/60 cold-adapted (ca) strain results from the combination of substitutions in three gene segments: PB1 K391E, PB1 E581G, PB2 N265S, and NP D34G (24). The cluster of ts mutations in the PA linker thus appears exceptional and may be related to its intrinsic disorder and its role in interacting and stabilizing the PB1 core and/or the positioning of the PA endonuclease in the polymerase complex. Thus, our results point out that ts mutations can be generated in immediate proximity to previously recognized ts mutations and that focusing on domains that are predicted to be flexible by themselves should also be an efficient strategy to generate ts mutants.

The engineering of amino acid substitutions for proline was carried out by single- or double-nucleotide substitutions, depending on the sequence of the mutated codon. Double-nucleotide substitutions, such as those corresponding to D216P (GAC to CCC) and F223P (TTC to CCC), precluded reversion to the wild-type codon by a single-nucleotide substitution. Thus, the isolation of escape mutants for D216P and F223P viruses, which recovered the inability to grow efficiently at 39.5°C and to have the PB1 subunit imported to the nucleus efficiently, allowed identification of more complex reversion mutations. The fact that we could isolate only three revertants, P216S (codon TCC), P216D (codon GAC), and P223H (codon CAC), suggests that residues 216 and 223 are critical for virus fitness at 39.5°C, with a proline being negatively selected at these positions while serine and histidine can substitute for the conserved D216 and F223, respectively. A proline at position 216 in a helix or at position 223 in a turn is expected to reduce the stability of these secondary structures and thus to promote a ts phenotype that is counterselected when mutants are grown at 39.5°C. In contrast, the T210P mutation appears to be less critical for virus fitness. Indeed, distant reversion mutations in PA, but also in PB1 and PB2 (observed in ts210/Rev5 and ts210/Rev6 [Table 3]) were selected when the T210P mutant was grown at 39.5°C. The PB1-R287M reversion (ts210/Rev6) that is distant from the PA linker is located at a PB1-PB2 interface. Even if the fact that these mutations are sufficient to mediate phenotypic reversion remains to be proven by reverse genetics experiments, we speculate that reversion in the T210P backbone to a non-ts phenotype by substitutions in PB1 or PB2 subunits may be related to the moderate ts phenotype of this mutant. Compensatory substitutions not directly affecting this phenotype but promoting higher replication/transcription efficiency may result in reversions to a wt phenotype. Conversely, we did not identify distant substitutions allowing reversions, with the D216P, L219P, and F223P mutations displaying strong ts phenotypes.

There is now a strong consensus that the PA and PB1 polymerase subunits require coexpression and must form a heterodimer in order to be efficiently targeted to the nucleus. We showed in this study that the PA linker, and more specifically the interaction of PA residues 210 to 226 with PB1, plays a role in the import of the PB1-PA heterodimer into the nucleus. At nonpermissive temperature (39.5°C), the transport of PB1 to the nucleus was altered when it was coexpressed with the PA ts mutants D216P, L219P, and F223P and with the PA lethal mutant L214P. The atomic structure of the polymerase (11) reveals a long, solvent-exposed, flexibly linked β-ribbon in PB1 (residues 177 to 212) (Fig. 1C). This element contains the PB1-nuclear localization signal (NLS) motifs, two separated basic patches (residues 187 to 190 and residues 207 to 211) that have been shown to be important for binding IPO5, the PA-PB1 heterodimer nuclear import factor (29, 38). This structure also revealed that the interaction between PA and PB1 in the polymerase involves, as previously recognized (40, 41, 42, 43), the carboxy-terminal domain of PA (mainly formed by helices from residues 583 to 716), which forms a deep, highly hydrophobic groove into which the amino-terminal residues of PB1 fit, as does the PA linker, and in particular the helix of residues 209 to 218 and the hairpin turn of residues 219 to 225, where ts and lethal substitutions were identified (11, 44, 45). These two segments lie on a large N-terminal domain of PB1 and are in close proximity to the PB1-NLS motifs. The residue 209 to 218 and residue 219 to 225 segments of the PA linker may thus constitute, in combination with the PB1-NLS motifs, the binding domain of IPO5 on the PA-PB1 complex. However, it should be noted that the PA linker residues we identified as critical for PB1 import could not be viewed as part of a conventional nuclear translocation signal, since arginine-lysine doublets were absent in the stretch from amino acids 210 to 226. We thus alternatively propose that this PA domain is critical for the assembly of a tripartite NLS constituted of the PB1-NLS motifs (residues 187 to 190 and residues 207 to 211) and another basic NLS in PA. The two PB1-NLS motifs could form an efficient tripartite NLS with the PA basic doublet (residues 124 and 125) and/or the segment containing residues 134 to 139, as its assembly is under the control of the PA linker. The facts that the PA stretch from residues 124 to 139 forms an α-helix (11, 17), is exposed to solvent, and contains one arginine-arginine doublet and three lysine gives credit to this hypothesis.

Another explanation for the importance of the helix formed by residues 209 to 218 and the turn of residues 219 to 225 could be related to a critical role of the PA linker in the acquisition of the native fold of PB1 or the stability of the PB1-PA complex. Assays to produce and purify recombinant PA-PB1 complexes with large subdomains of PA and PB1 have been shown to require the presence of the PA linker, thus appearing necessary for PA-PB1 complex stability (T. Crépin, personal communication).

The L214P virus mutant failed to be rescued, a hallmark in agreement with the absence of detectable RNA polymerase activity for PA L214P at all the tested temperatures in the minigenome assay (Fig. 6). However, PA L214P exhibited a less-pronounced defect than PA F223P (which allowed virus mutant recovery) in promoting PB1 translocation to the nucleus at 33°C (Fig. 7). These observations suggest that RNA synthesis activity per se may also be affected by the L214P mutation.

ts mutations fall into two general classes: those generating thermolabile proteins, and those generating defects in protein synthesis, folding, or assembly (46). We demonstrated that proline substitutions in the segment from residues 210 to 226 of the PA linker modulate correct assembly of the PA-PB1 heterodimer at restrictive temperature, suggesting that theses mutations are of the latter class. A ts mutation was also recently identified in the PA endonuclease at position 35 (47). The PA-35 residue is not accessible to solvent, suggesting that the determinism of the thermo-sensitivity of the PA linker ts mutants and the F35S mutant differ, the latter possibly modulating the folding (and as a consequence the endonuclease activity) of the N-terminal domain of the protein. The FluMist influenza A virus live attenuated vaccine strain contains determinants of temperature sensitivity in the PB1, PB2, and NP genes (24). It is interesting that the two ts mutations in PB1 (K391E and E581G) are located in external helices, possibly affecting locally the folding and/or recognition of PB1 by cellular partners, similar to what we observed with PA ts mutants.

Introducing a single substitution at residue 216 or 219 of the PA linker induces a strong attenuation of the resulting mutants, with LD50 values of 5.5 and >6, respectively, while an LD50 of 3.5 was found for the parental virus. To our knowledge, such a level of attenuation with a single substitution in influenza viruses has only be found once, with the substitution of a phenylalanine to a serine at position 35 of PA (in its endonuclease domain and in an H9N2 backbone [47]). For the FluMist influenza A virus vaccine strain, the ts phenotype results from the combination of mutations present on three segments (PB1 with K391E and E581G, PB2 with N265S, and NP with D34G), but not on the PA segment. Engineering recombinant viruses harboring ts mutations in all the segments encoding subunits of the replicative complex (namely PA, PB1, PB2, and NP) could be a valuable tool to produce live vaccine strains that would be incompetent for reassortment with seasonal viruses.

Mice inoculated with a mouse-adapted influenza virus show a fall in body temperature (48). While the normal body temperature of mice is 36.9°C, it can decrease to 33°C in infected mice. We did not observe at these temperatures any decrease of replication of virus mutants in vitro, thus suggesting that the ability to replicate at a given temperature and the level of attenuation in mice are not strictly correlated.

Taken altogether, our results identified a key flexible domain in PA as a hot spot to engineer ts mutants. This domain, which lies at the surface of PB1, appears critical for the assembly and the nuclear import of the PB1-PA heterodimer and may be used to design new attenuated vaccines and antiviral drugs in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Damien Vitour for his help to generate the anti-PA rabbit polyclonal antibody. We thank Thibaut Crépin and Rob Ruigrok for helpful discussions.

B.D. acknowledges the support of the ANR Blanc program (RNAP-IAV project), the support of Institut Carnot Santé Animale (Flu-MLI project), and the support of Paris-Saclay University (Programme prévalorisation 2014). N.N. acknowledges the support of the Institut Carnot Pasteur Maladies Infectieuses and of the European Commission-funded FP7 project FLUPHARM, grant agreement 259751.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaw M, Palese P. 2013. Orthomyxoviridae, p 1151–1185. In Knipe DM, Howley P (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed, vol 1 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boivin S, Cusack S, Ruigrok RW, Hart DJ. 2010. Influenza A virus polymerase: structural insights into replication and host adaptation mechanisms. J Biol Chem 285:28411–28417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.117531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulo S, Akarsu H, Ruigrok RW, Baudin F. 2007. Nuclear traffic of influenza virus proteins and ribonucleoprotein complexes. Virus Res 124:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honda A, Ishihama A. 1997. The molecular anatomy of influenza virus RNA polymerase. Biol Chem 378:483–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng T, Sharps J, Fodor E, Brownlee GG. 2005. In vitro assembly of PB2 with a PB1-PA dimer supports a new model of assembly of influenza A virus polymerase subunits into a functional trimeric complex. J Virol 79:8669–8674. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8669-8674.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fodor E, Smith M. 2004. The PA subunit is required for efficient nuclear accumulation of the PB1 subunit of the influenza A virus RNA polymerase complex. J Virol 78:9144–9153. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9144-9153.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huet S, Avilov SV, Ferbitz L, Daigle N, Cusack S, Ellenberg J. 2010. Nuclear import and assembly of influenza A virus RNA polymerase studied in live cells by fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy. J Virol 84:1254–1264. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01533-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald LA, Aggarwal S, Bussey KA, Desmet EA, Kim B, Takimoto T. 2012. Molecular interactions and trafficking of influenza A virus polymerase proteins analyzed by specific monoclonal antibodies. Virology 426:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruigrok RW, Crépin T, Hart DJ, Cusack S. 2010. Towards an atomic resolution understanding of the influenza virus replication machinery. Curr Opin Struct Biol 20:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poch O, Sauvaget I, Delarue M, Tordo N. 1989. Identification of four conserved motifs among the RNA-dependent polymerase encoding elements. EMBO J 8:3867–3874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pflug A, Guilligay D, Reich S, Cusack S. 2014. Structure of influenza A polymerase bound to the viral RNA promoter. Nature 516:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature14008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klumpp K, Ruigrok RW, Baudin F. 1997. Roles of the influenza virus polymerase and nucleoprotein in forming a functional RNP structure. EMBO J 16:1248–1257. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomescu AI, Robb NC, Hengrung N, Fodor E, Kapanidis AN. 2014. Single-molecule FRET reveals a corkscrew RNA structure for the polymerase-bound influenza virus promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E3335–E3342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406056111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biswas SK, Nayak DP. 1994. Mutational analysis of the conserved motifs of influenza A virus polymerase basic protein 1. J Virol 68:1819–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaas D, Patzelt E, Kuechler E. 1982. Identification of the cap binding protein of influenza virus. Nucleic Acids Res 10:4803–4812. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.15.4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulmanen I, Broni BA, Krug RM. 1981. Role of two of the influenza virus core P proteins in recognizing cap 1 structures (m7GpppNm) on RNAs and in initiating viral RNA transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78:7355–7359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reich S, Guilligay D, Pflug A, Malet H, Berger I, Crépin T, Hart D, Lunardi T, Nanao M, Ruigrok RW, Cusack S. 2014. Structural insight into cap-snatching and RNA synthesis by influenza polymerase. Nature 516:361–366. doi: 10.1038/nature14009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dias A, Bouvier D, Crépin T, McCarthy AA, Hart DJ, Baudin F, Cusack S, Ruigrok RW. 2009. The cap-snatching endonuclease of influenza virus polymerase resides in the PA subunit. Nature 458:914–918. doi: 10.1038/nature07745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan P, Bartlam M, Lou Z, Chen S, Zhou J, He X, Lv Z, Ge R, Li X, Deng T, Fodor E, Rao Z, Liu Y. 2009. Crystal structure of an avian influenza polymerase PA(N) reveals an endonuclease active site. Nature 458:909–913. doi: 10.1038/nature07720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fodor E, Crow M, Mingay LJ, Deng T, Sharps J, Fechter P, Brownlee GG. 2002. A single amino acid mutation in the PA subunit of the influenza virus RNA polymerase inhibits endonucleolytic cleavage of capped RNAs. J Virol 76:8989–9001. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.8989-9001.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jagger BW, Wise HM, Kash JC, Walters KA, Wills NM, Xiao YL, Dunfee RL, Schwartzman LM, Ozinsky A, Bell GL, Dalton RM, Lo A, Efstathiou S, Atkins JF, Firth AE, Taubenberger JK, Digard P. 2012. An overlapping protein-coding region in influenza A virus segment 3 modulates the host response. Science 337:199–204. doi: 10.1126/science.1222213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garaigorta U, Falcón AM, Ortín J. 2005. Genetic analysis of influenza virus NS1 gene: a temperature-sensitive mutant shows defective formation of virus particles. J Virol 79:15246–15257. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15246-15257.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noton SL, Simpson-Holley M, Medcalf E, Wise HM, Hutchinson EC, McCauley JW, Digard P. 2009. Studies of an influenza A virus temperature-sensitive mutant identify a late role for NP in the formation of infectious virions. J Virol 83:562–571. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01424-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin H, Lu B, Zhou H, Ma C, Zhao J, Yang CF, Kemble G, Greenberg H. 2003. Multiple amino acid residues confer temperature sensitivity to human influenza virus vaccine strains (FluMist) derived from cold-adapted A/Ann Arbor/6/60. Virology 306:18–24. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(02)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Treanor J, Perkins M, Battaglia R, Murphy BR. 1994. Evaluation of the genetic stability of the temperature-sensitive PB2 gene mutation of the influenza A/Ann Arbor/6/60 cold-adapted vaccine virus. J Virol 68:7684–7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pena L, Vincent AL, Ye J, Ciacci-Zanella JR, Angel M, Lorusso A, Gauger PC, Janke BH, Loving CL, Perez DR. 2011. Modifications in the polymerase genes of a swine-like triple-reassortant influenza virus to generate live attenuated vaccines against 2009 pandemic H1N1 viruses. J Virol 85:456–469. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01503-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou B, Li Y, Speer SD, Subba A, Lin X, Wentworth DE. 2012. Engineering temperature sensitive live attenuated influenza vaccines from emerging viruses. Vaccine 30:3691–3702. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawaguchi A, Naito T, Nagata K. 2005. Involvement of influenza virus PA subunit in assembly of functional RNA polymerase complexes. J Virol 79:732–744. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.732-744.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng T, Engelhardt OG, Thomas B, Akoulitchev AV, Brownlee GG, Fodor E. 2006. Role of Ran binding protein 5 in nuclear import and assembly of the influenza virus RNA polymerase complex. J Virol 80:11911–11919. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01565-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fodor E, Devenish L, Engelhardt OG, Palese P, Brownlee GG, García-Sastre A. 1999. Rescue of influenza A virus from recombinant DNA. J Virol 73:9679–9682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Goffic R, Bouguyon E, Chevalier C, Vidic J, Da Costa B, Leymarie O, Bourdieu C, Decamps L, Dhorne-Pollet S, Delmas B. 2010. Influenza A virus protein PB1-F2 exacerbates IFN-beta expression of human respiratory epithelial cells. J Immunol 185:4812–4823. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leymarie O, Jouvion G, Hervé PL, Chevalier C, Lorin V, Lecardonnel J, Da Costa B, Delmas B, Escriou N, Le Goffic R. 2013. Kinetic characterization of PB1-F2-mediated immunopathology during highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza virus infection. PLoS One 8:e57894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cassonnet P, Rolloy C, Neveu G, Vidalain PO, Chantier T, Pellet J, Jones L, Muller M, Demeret C, Gaud G, Vuillier F, Lotteau V, Tangy F, Favre M, Jacob Y. 2011. Benchmarking a luciferase complementation assay for detecting protein complexes. Nat Methods 8:990–992. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munier S, Rolland T, Diot C, Jacob Y, Naffakh N. 2013. Exploration of binary virus-host interactions using an infectious protein complementation assay. Mol Cell Proteomics 12:2845–2855. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.028688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Goffic R, Leymarie O, Chevalier C, Rebours E, Da Costa B, Vidic J, Descamps D, Sallenave JM, Rauch M, Samson M, Delmas B. 2011. Transcriptomic analysis of host immune and cell death responses associated with the influenza A virus PB1-F2 protein. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002202. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LeGoff J, Rousset D, Abou-Jaoudé G, Scemla A, Ribaud P, Mercier-Delarue S, Caro V, Enouf V, Simon F, Molina JM, van der Werf S. 2012. I223R mutation in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 neuraminidase confers reduced susceptibility to oseltamivir and zanamivir and enhanced resistance with H275Y. PLoS One 7:e37095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robb NC, Smith M, Vreede FT, Fodor E. 2009. NS2/NEP protein regulates transcription and replication of the influenza virus RNA genome. J Gen Virol 90:1398–1407. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.009639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hutchinson EC, Orr OE, Man Liu S, Engelhardt OG, Fodor E. 2011. Characterization of the interaction between the influenza A virus polymerase subunit PB1 and the host nuclear import factor Ran-binding protein 5. J Gen Virol 92:1859–1869. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.032813-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang S, Sun D, Liang H, Wang J, Li J, Guo L, Wang X, Guan C, Boruah BM, Yuan L, Feng F, Yang M, Wang L, Wang Y, Wojdyla J, Li L, Wang J, Wang M, Cheng G, Wang HW, Liu Y. 2015. Cryo-EM structure of influenza virus RNA polymerase complex at 4.3 Å resolution. Mol Cell 57:925–935. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zürcher T, de la Luna S, Sanz-Ezquerro JJ, Nieto A, Ortín J. 1996. Mutational analysis of the influenza virus A/Victoria/3/75 PA protein: studies of interaction with PB1 protein and identification of a dominant negative mutant. J Gen Virol 77:1745–1749. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-8-1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez DR, Donis RO. 2001. Functional analysis of PA binding by influenza a virus PB1: effects on polymerase activity and viral infectivity. J Virol 75:8127–8136. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.8127-8136.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohtsu Y, Honda Y, Sakata Y, Kato H, Toyoda T. 2002. Fine mapping of the subunit binding sites of influenza virus RNA polymerase. Microbiol Immunol 46:167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghanem A, Mayer D, Chase G, Tegge W, Frank R, Kochs G, García-Sastre A, Schwemmle M. 2007. Peptide-mediated interference with influenza A virus polymerase. J Virol 81:7801–7804. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00724-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He X, Zhou J, Bartlam M, Zhang R, Ma J, Lou Z, Li X, Li J, Joachimiak A, Zeng Z, Ge R, Rao Z, Liu Y. 2008. Crystal structure of the polymerase PA(C)-PB1(N) complex from an avian influenza H5N1 virus. Nature 454:1123–1126. doi: 10.1038/nature07120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Obayashi E, Yoshida H, Kawai F, Shibayama N, Kawaguchi A, Nagata K, Tame JR, Park SY. 2008. The structural basis for an essential subunit interaction in influenza virus RNA polymerase. Nature 454:1127–1131. doi: 10.1038/nature07225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gordon CL, King J. 1994. Genetic properties of temperature-sensitive folding mutants of the coat protein of phage P22. Genetics 136:427–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang W, Tu J, Zhao Z, Chen H, Jin M. 2012. The new temperature-sensitive mutation PA-F35S for developing recombinant avian live attenuated H5N1 influenza vaccine. Virol J 9:97–102. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klein MS, Conn CA, Kluger MJ. 1992. Behavioral thermoregulation in mice inoculated with influenza virus. Physiol Behav 52:1133–1139. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90472-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]