Abstract

Background

Studies investigating the associations between transcription factor 4 (TCF4) genetic polymorphisms and Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy (FED) have reported controversial results. Therefore, this meta-analysis aims to clarify the effects of TCF4 polymorphisms on FED risk.

Methods

A meta-analysis was conducted to assess the association between four single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) inTCF4 and the risk of FED. Relevant studies were selected through an extensive search of PubMed, EMBASE, and the Web of Science databases. Pooled odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence interval (CI) were calculated using the random-effects model.

Results

Thirteen studies were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The pooled results showed that there was a strong positive association between the TCF4 rs613872 polymorphism and FED risk in all the genetic models tested (G allele vs. T allele: OR = 4.19, 95 % CI = 3.53–4.97; GG vs. GT/TT: OR = 4.27, 95 % CI = 2.54–7.19; GG/GT vs. TT: OR = 6.29, 95 % CI = 4.23–8.93; GG VS. TT: OR = 10.64, 95 % CI = 5.28–21.41; GT VS. TT: OR = 6.08, 95 % CI = 4.28–8.64). Statistic evidence was also detected for a significant association between three other SNPs and the risk of FED.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis suggested a genetic association between four TCF4 polymorphisms (rs613872, rs2286812, rs17595731, and rs9954153) and the risk of FED.

Background

Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy (FED) is a familial, slowly progressive, and irreversible disorder affecting the corneal endothelial cell monolayer [1]. It has been reported that, in the United States, FED affects about 4 % of the population over the age of forty [2], making it the most common genetic disorder of the corneal endothelium. The most important signs of FED are the thickening of Descemet’s membrane and microscopic collagenous excrescences known asguttae [3]. Disease progression results in reduced vision as a result of the edema in the cornea, which is caused by loss of the fluid-pumping function of the endothelium [4].

Although the precise reason for FED remains unclear, recent studies have reported significant insights into the genetic basis of the disorder. To date, several gene mutations, such as collagen type 8 alpha-2 (COL8A2), the sodium borate cotransporter gene (SLC4A11), transcription factor 8 (TCF8), and transcription factor 4 (TCF4), have been implicated in the pathogenesis of FED [5–8]. Of these gene mutations, the TCF4 variations have been considered to be associated with a number of diseases, such as FED, schizophrenia, and primary sclerosing cholangitis [8–10]. The TCF4 gene is located on chromosome 18q [11]. It encodes a transcription factor protein, E2-2, which is a member of the E protein family that is expressed in the cornea during development and which is involved in regulating cellular growth and differentiation [12].

Recently, TCF4 polymorphisms have attracted a lot of attention. A previous genome-wide association study (GWAS) showed a significant relationship between FED and four genotyped single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (rs17595731, rs613872, rs9954153, and rs2286812) of the TCF4 gene [8]. Since then, several case–control studies have also been conducted and they have also shown that the TCF4 polymorphisms are associated with FED [8, 13–16]. However, these results remain inconclusive. For example, Nanda et al. [17] reported that the TCF4 rs613872 polymorphism was not associated with FED, but Kuot et al. [11] found that the TCF4 rs613872 polymorphism was a risk factor for FED. Other SNPs of TCF4 (rs2286812, rs17595731, and rs9954153) were also analyzed in some FED genetic association studies.

Meta-analysis is a powerful statistical technique that is often used in combination with different studies; therefore, it draws a more comprehensive conclusion. With this in mind, we conducted a meta-analysis to summarize all the relevant evidence for an association between the risk of FED and genetic polymorphisms of TCF4, which include four SNPs: rs17595731, rs613872, rs9954153, and rs2286812.

Methods

Literature search

Literature searches were performed in PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), ISI Web of Science (www.webofknowledge.com), and EMBASE (http://www.embase.com) databases. Key search terms included (“Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy,” or “Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy,”) and (“transcription factor 4,” or “TCF4,”or “immunoglobulin transcription factor 2,” or “E2-2,” or “SL3-3 enhancer factor 2,” or “SEF2,” or “rs613872,” “rs17595731” or “rs2286812” OR “rs9954153”) and (“polymorphism,” or “variation,” or “mutation,” or “variant,” or “genotype,” or “allele”). References cited in each eligible literature were manual checked until no further studies were found. If the overlapping patient population was included in several studies, the latest study was included. The final literature search was updated on April 05, 2015, with no restrictions as to publication year, language, or methodological filter.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies included in this meta-analysis were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: (a) designed as nested case–control, case–control, or GWAS; (b) evaluated TCF4 polymorphism and FED; (c) odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95 % confidence interval (CI) were provided; and (d) sufficient genotypic or allelic information was provided to estimate. Exclusion criteria were: (a) case-only studies, familial studies, or duplicate data; (b) abstracts, comments, letters, reviews, or editorial articles; (c) insufficient genotyping data.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two observers (L.D. and S.H.Y.) independently extracted the following information from included studies, using a standardized data extraction form: first author, year of publication, country of origin, population ethnicity, source of controls, numbers of genotyped cases and controls, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) for the control group. If a study provided several risk estimates, the best adjusted estimate was extracted. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or adjudicated with the involvement of a third reviewer (P.X.Y.). The quality of each study was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [18]. The NOS uses a “star” rating system to judge quality, based on three aspects of the study: selection, comparability, and exposure; scores range from 0 stars (worst) to 9 stars (best). Studies with a score of ≥ 7 were considered of high quality [19]. Any discrepancies were addressed by means of discussion and consensus.

Statistical analyses

ORs and 95 % CIs were used to assess the strength of the associations between TCF4 polymorphisms and FED. Adjusted ORs and 95%CIs were used if they were reported; otherwise, the pooled ORs and 95 % CIs without adjustments were calculated for the following genotypic models for rs613872 SNP: allele (G vs. T); homozygote (GG vs. TT), heterozygote (GT vs. TT), dominant (GG/GT vs. TT), and recessive (GG vs. GT/TT). Due of the insufficient data for the other three TCF4 SNPs, the pooled ORs and the 95 % CIs were calculated using an additive model. Data were combined using a random effects model to achieve more conservative estimates. Statistical heterogeneity between the studies was evaluated using Cochran’s Q test and the I2 statistic. For the Q statistic, p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistically significant heterogeneity [20]. I2 was also used to assess the heterogeneity in the meta-analysis, and heterogeneity was said to exist when I2 > 50 % [21]. To determine the reliability of the outcomes of the meta-analysis, a sensitivity analysis was performed by the exclusion of an individual study each time. Furthermore, we repeated the sensitivity analyses to delete the findings from studies that deviated from the HWE principle [22] and to calculate the pooled ORs for the remainder of the studies [8, 13–17, 23–25]. Finally, to detect publication biases, Begg’s and Egger’s measures were calculated and assessed using Begg’s funnel plots [26, 27]. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant in the test for overall effect. The analysis was conducted using the Stata software package (Version 12.0; Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Literature search and characteristics

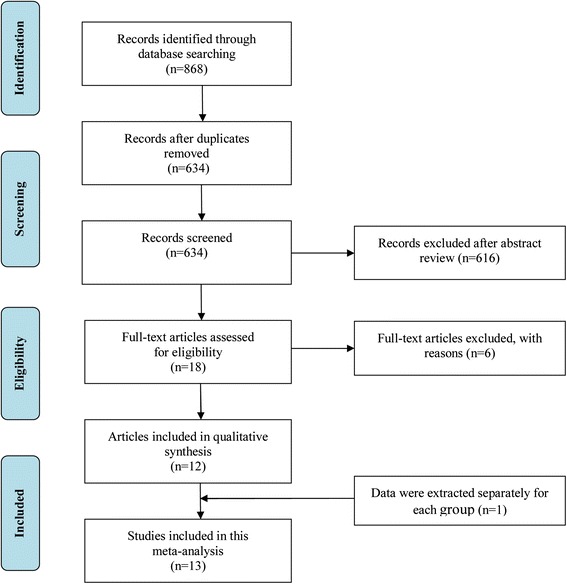

The initial search yielded 868 potentially relevant studies. After the removal of duplicates through electronic databases, 634 studies remained. Based on titles and abstracts, 616 articles were excluded because of their apparent irrelevance. In total, 18 full-text articles were further assessed for eligibility. Of these, six articles were excluded for the following reasons: the article was a review (n = 1) [28]; the articles lacked controls (n = 3) [29–31]; and the articles did not focus on the relative polymorphism (n = 2) [32, 33]. Finally, 12 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in this meta-analysis [8, 13–17, 22–25, 34, 35]. One trial [8], reported the allele and the genotype of the discovery group and the replication group, respectively. We assumed that the discovery group and the replication group were the subjects in two separate studies. Overall, 13 studies were included in this meta-analysis. Of these, 11 studies reported the association between the TCF4 rs613872 polymorphism and FED. Three studies reported the association between the TCF4 rs9954153 polymorphism and FED. Three studies reported the association between the TCF4 rs17595731 polymorphism and FED. Five studies reported the association between the TCF4 rs2286812 polymorphism and FED. The study selection process is detailed in Fig. 1. The main characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1. Among these studies, nine originated from the United States, one from Australia, one from India, one from China, and one from Singapore. Thirteen studies included 2468 FED cases and 2902 controls. The NOS results showed that the average score was 7.9 (range: 7 to 9), indicating that the methodological quality was generally good.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram outlining the selection process for inclusion of studies in the systematic review and meta-analysis

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| First Author (year) | Country | Ethnicity | Study design | Genotyping method | Case/Control | Source of control | SNP | HW-E test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baratz (2010)a [8] | USA | Caucasian | GWAS | Taqman assay | 130/260 | HB | rs613872,rs17595731, | yes |

| rs9954153,rs2286812 | ||||||||

| Baratz (2010)b [8] | USA | Caucasian | GWAS | Taqman assay | 150/150 | HB | rs613872,rs17595731, | yes |

| rs9954153,rs2286812 | ||||||||

| Li (2011) [23] | USA | Caucasian | Case–control | Taqman assay | 450/340 | HB | rs613872 | yes |

| Riazuddin (2011) [24] | USA | Caucasian | Case–control | Taqman assay | 170/180 | HB | rs613872 | yes |

| Thalamuthu (2011) [34] | Singapore | Asian | Case–control | MassArray | 57/121 | HB | rs2286812 | yes |

| Igo (2012) [22] | USA | Caucasian | Case–control | Taqman assay | 531/204 | HB | rs613872 | no |

| Kuot (2012) [16] | Australia | Caucasian | Case–control | MassArray | 103/275 | HB | rs613872,rs9954153, | yes |

| rs2286812,rs17595731 | ||||||||

| Stamler (2013) [15] | USA | Caucasian | Case–control | Taqman assay | 82/163 | HB | rs613872 | yes |

| Nanda (2014) [17] | India | Asian | Case–control | PCR-sequencing | 44/108 | HB | rs613872 | yes |

| Wang (2014) [35] | China | Asian | Case–control | Taqman assay | 34/491 | HB | rs2286812 | yes |

| Li (2014) [19] | USA | Caucasian | Case–control | Taqman assay | 529/494 | HB | rs613872 | yes |

| Mootha (2014) [13] | USA | Caucasian | Case–control | Taqman assay | 120/100 | HB | rs613872 | yes |

| Wieben (2014) [25] | USA | Caucasian | Case–control | PCR-sequencing | 68/16 | HB | rs613872 | yes |

HW-E Hardy Weinberg equilibrium; PCR polymerase chain reaction; HB hospital-based

aThe data extracted from discovery group

bThe data extracted from replication group

Meta-analysis of TCF4 rs613872polymorphism and FED

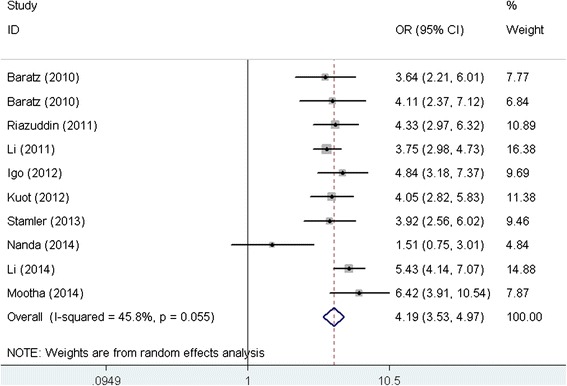

Table 2 presents the main results of the pooled ORs and the heterogeneity test of the meta-analysis. For rs613872, the pooled ORs showed that there was a strong positive association between the TCF4 rs613872 polymorphism and FED risk in all the genetic models tested (G allele vs. T allele: OR = 4.19, 95 % CI = 3.53–4.97 (Fig. 2); GG vs. GT/TT: OR = 4.27, 95 % CI = 2.54–7.19; GG/GT vs. TT: OR = 6.29, 95 % CI = 4.23–8.93; GG vs.TT: OR = 10.64, 95 % CI = 5.28–21.41; GT vs. TT: OR = 6.08, 95 % CI = 4.28–8.64). Among the studies, significant heterogeneity was detected in the dominant model (GG/GT vs. TT) and the heterozygote model (GT vs. TT) (Table 2). For rs2286812, five studies were included for calculation and the pooled ORs and 95%CI was 1.77(1.19–2.63) in the additive model, which also showed a genetic association with the risk of FED. Significant associations were also observed for rs17595731 and rs9954153 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of meta-analysis for TCF4 polymorphisms and risk of FED

| Polymorphism (comparison) | No. of studies | OR (95%CI) | P | Heterogeneity | P Egger’s testa | P Begg’s testb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x 2 | I2 | P | ||||||

| rs613872 | ||||||||

| G vs. T | 10 | 4.19(3.53–4.97) | <0.001 | 16.60 | 45.8 % | 0.055 | 0.411 | 0.474 |

| GG vs. GT/TT | 6 | 4.27(2.54–7.19) | <0.001 | 6.20 | 19.3 % | 0.288 | 0.295 | 0.260 |

| GG/GT vs. TT | 7 | 6.29(4.23–8.93) | <0.001 | 16.23 | 63.0 % | 0.013 | 0.586 | 0.707 |

| GG VS. TT | 6 | 10.64(5.28–21.41) | <0.001 | 9.43 | 47.0 % | 0.093 | 0.378 | 0.452 |

| GT VS. TT | 6 | 6.08 (4.28–8.64) | <0.001 | 12.72 | 60.7 % | 0.026 | 0.938 | 0.707 |

| rs2286812 | ||||||||

| T vs C | 5 | 1.77(1.19–2.63) | 0.005 | 12.10 | 66.9 % | 0.017 | 0.207 | 0.180 |

| rs17595731 | ||||||||

| C vs G | 3 | 4.70(3.06–7.21) | <0.001 | 1.27 | 0.0 % | 0.530 | 0.775 | 1.000 |

| rs9954153 | ||||||||

| G vs T | 3 | 2.43(1.97–3.01) | <0.001 | 0.20 | 0.0 % | 0.906 | 0.793 | 1.000 |

TCF4 transcription factor 4; FED Fuchs endothelial dystrophy; OR odds ratio; CI confidence Interval

a P Egger’s test = the P value for Egger’s test

b P Begg’s test = the P value for Begg’s test

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for the association between TCF4 rs613872 polymorphism and FED risk (G allele vs. T allele). OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; TCF4: transcription factor 4; FED: Fuchs endothelial dystrophy

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

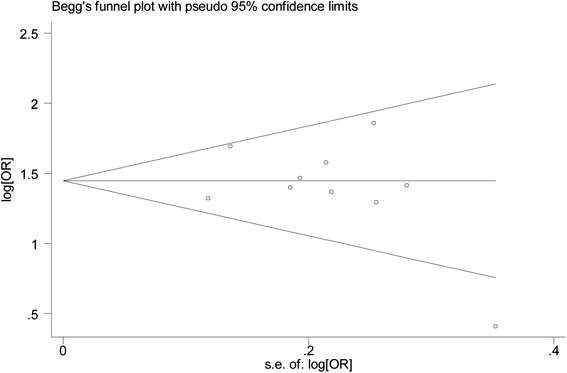

To evaluate the influence of an individual data set on the pooled results, one study was deleted at a time. The estimates were not altered substantially when any single study was deleted, suggesting the high stability of the meta-analysis results for TCF4 rs613872 (Table 3). This analysis of the association between theTCF4 rs613872 polymorphism and FED risk also revealed that one study by Nanda et al. [17] was the main origin of heterogeneity (Table 3). The I2 significantly declined from 45.8 % to 0.0 % (Q = 7.69, p = 0.464) after removing the study by Nanda et al. It is interesting to note that when one study that deviated from the HWE principle was deleted [22], the results from the remaining studies were similar to the overall result, and a significant association was detected in all the genetic models. We also performed “leave-one-out” sensitivity analyses for the other three SNPs and the results showed that no single study influenced the pooled results (data not shown). Publication bias was estimated using Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test (Table 2). No significant publication bias was observed in this meta-analysis. In addition, the funnel plot for studies of the association between theTCF4 rs613872 polymorphism and FED risk under an additive model (G allele vs. T allele) is presented in Fig. 3.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis of the meta-analysis results for TCF4 rs613872 polymorphism and FED risk (G allele vs. T allele)

| Random effects model | Test of homogeneity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Excluded | OR | 95%CI | Q | I2 (%) | P-value |

| None | 4.19 | 3.53–4.97 | 16.60 | 45.8 | 0.055 |

| Baratz (2010)a [8] | 4.23 | 3.52–5.09 | 16.22 | 50.7 | 0.039 |

| Baratz (2010)b [8] | 4.19 | 3.48–5.04 | 16.58 | 51.8 | 0.035 |

| Li (2011) [23] | 4.26 | 3.50–5.19 | 15.12 | 47.1 | 0.057 |

| Riazuddin (2011) [24] | 4.16 | 3.43–5.04 | 16.59 | 51.8 | 0.035 |

| Igo (2012) [22] | 4.11 | 3.41–4.96 | 16.20 | 50.6 | 0.040 |

| Kuot (2012) [16] | 4.19 | 3.46–5.09 | 16.53 | 51.6 | 0.035 |

| Stamler (2013) [15] | 4.21 | 3.48–5.08 | 16.46 | 51.4 | 0.036 |

| Nanda (2014) [17] | 4.38 | 3.89–4.94 | 7.69 | 0.0 | 0.464 |

| Li (2014) [19] | 4.01 | 3.37–4.78 | 12.57 | 51.4 | 0.042 |

| Mootha (2014) [13] | 4.05 | 3.42–4.80 | 13.78 | 41.9 | 0.088 |

TCF4 transcription factor 4; FED Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy; OR odds ratio; CI confidence Interval

aThe data extracted from discovery group

bThe data extracted from replication group

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot for studies of the association of TCF4 rs613872 polymorphism and FED risk (G allele vs. T allele). OR: odds ratio; TCF4: transcription factor 4; FED: Fuchs endothelial dystrophy

Discussion

Despite the fact that the GWAS publication noted that genetic variations in TCF4 polymorphisms contribute to the development of FED, this correlation also needs to be verified by a case control study. Therefore, we performed this meta-analysis to provide the highest level of evidence for the association between TCF4 polymorphisms and the risk of FED. With a total of 5370 participants, this meta-analysis focused on the association between TCF4 variants and the risk of FED, thirteen studies addressing one or more SNPs in TCF4 (rs613872, rs17595731, rs9954153, and rs2286812) were included. The pooled results showed that a significant association was detected between FED risk and the rs17595731, rs613872, rs9954153, and rs2286812 SNPs. This s consistent with the findings presented in the GWAS publication [8]. For rs613872, in order to achieve robust and reliable results for the meta-analysis of the association between rs613872 and FED risk, we performed a series of analyses. These sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding one individual study each time. This procedure did not greatly change the pooled results; rather, it supported their reliability. In addition, it should be noted that the genetic distributions of the controls in one study deviated from HWE, indicating the possibility of bias. Thus, we conducted the sensitivity analyses again, omitting that study. The results from the pooled ORs before and after omitting the studies that deviated from the studies that used the HWE principles were similar, suggesting that the results were minimally affected by this study. In addition, for the other SNPs, no individual study influenced the pooled results Furthermore, no significant publication bias was observed in the pooled results in all four of the SNPs, further demonstrating the robustness of our meta-analysis.

Differences in ethnic groups may affect genetic predisposition to human diseases [36, 37]. In the present meta-analysis, we found that only one study from India did not detect the association between the TCF4 rs613872 polymorphism and the risk of FED, which might be due to the different ethnicity of the included study participants [17]. Another study from Asian also showed no association between rs2286812 and the risk of FED, which also might be due to the different ethnicity of the study population. However, only one study with a small sample size should be considered. In the future, more epidemiologic studies of people with Asian ethnicity using larger sample sizes are needed to further confirm this difference.

To date, the pathomechanism underlying the association between the TCF4 gene and FED risk is still unclear. Possible mechanisms for the association between the TCF4 gene and FED risk have been proposed. First, the protein produced by the TCF4 gene (E2-2) might participate in endothelium growth, proliferation, and differentiation [38]. Therefore, loss of function in this protein through gene mutations would reduce the number of endothelial cells, as observed in FED patients [8]. In addition, the E2-2 protein has been shown to up-regulate the protein expression of zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1), which has been found to be the pathogenic protein of FED. Thus, this indirectly showed that the TCF4 gene mutation associated with FED results from changes in the expression of ZEB1 [8]. Taken together, these proofs supported the hypothesis that the TCF4 gene might heighten the risk of FED.

An important aim of meta-analysis is to determine the sources of heterogeneity. In this meta-analysis, substantial heterogeneity was observed in the dominant model (I2 = 63.0 %; p = 0.013), and the heterozygote model (I2 = 60.7 %; p = 0.026) for rs613872. We performed the sensitivity analysis by exclusion of one individual study each time and we found that the study by Nanda et al. [17] might be the source of heterogeneity, as heterogeneity was significantly decreased after excluding that study. For rs2286812, substantial heterogeneity was also observed in the additive model and the sensitivity analysis also showed that Wang’s [35] study is the source of the heterogeneity.

In performing a quantitative analysis of the relationship between TCF4 polymorphisms and FED risk, this meta-analysis was also limited. First, the number of original studies included in the meta-analysis was relatively small; for rs17595731, rs9954153, and rs2286812, only three to five studies were included. Second, substantial heterogeneity was observed among the studies. However, we determined that the source of this heterogeneity was the single study from India for rs613872. When this study was excluded, the results of the remaining studies did not change, and the heterogeneity was greatly reduced. Third, the genotyping methods differed among these studies, which may have affected the results. Fourth, it should be noted that the HWE test was not performed in one of the studies, which may have increased selection bias in the control. However, when that study was excluded the summary OR was unchanged in the remaining studies, which suggested the high stability of the results of this meta-analysis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this meta-analysis suggested a genetic association between four TCF4 polymorphisms (rs613872, rs2286812, rs17595731, and rs9954153) and the risk of FED. Despite these encouraging findings, the inherent limitations of the studies should be considered, and conclusions drawn from the pooled results should be interpreted with caution. In the future, more epidemiologic studies of other ethnicities with a well-designed and larger sample size are needed to further confirm our findings.

Acknowledgments

We do not have anyone or any sources of funding to acknowledge.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors conceived of and designed the experimental protocol. DL collected the data. All authors were involved in the analysis. DL and HS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. XP and HS reviewed and revised the manuscript and produced the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dan Li, Email: 2770688345@qq.com.

XiaoYan Peng, Phone: +86-10-58265900, Email: drpengxy@163.com.

HuiYu Sun, Email: sunhuiyu123@126.com.

References

- 1.Adamis AP, Filatov V, Tripathi BJ, Tripathi RC. Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy of the cornea. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;38:149–68. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(93)90099-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krachmer JH, Purcell JJ, Young CW, Bucher KD. Corneal endothelial dystrophy. A study of 64 families. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:2036–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1978.03910060424004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottsch JD, Sundin OH, Rencs EV, Emmert DG, Stark WJ, Cheng CJ, Schmidt GW. Analysis and documentation of progression of Fuchs corneal dystrophy with retroillumination photography. Cornea. 2006;25:485–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000178726.11693.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goar EL. Dystrophy of the Corneal Endothelium (Cornea Guttata), with Report of a Histologic Examination. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1933;31:48–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riazuddin SA, Parker DS, McGlumphy EJ, Oh EC, Iliff BW, Schmedt T, Jurkunas U, Schleif R, Katsanis N, Gottsch JD. Mutations in LOXHD1, a recessive-deafness locus, cause dominant late-onset Fuchs corneal dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:533–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riazuddin SA, Vithana EN, Seet LF, Liu Y, Al-Saif A, Koh LW, Heng YM, Aung T, Meadows DN, Eghrari AO, et al. Missense mutations in the sodium borate cotransporter SLC4A11 cause late-onset Fuchs corneal dystrophy. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:1261–8. doi: 10.1002/humu.21356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forrest MP, Hill MJ, Quantock AJ, Martin-Rendon E, Blake DJ. The emerging roles of TCF4 in disease and development. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baratz KH, Tosakulwong N, Ryu E, Brown WL, Branham K, Chen W, Tran KD, Schmid-Kubista KE, Heckenlively JR, Swaroop A, et al. E2-2 protein and Fuchs’s corneal dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1016–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan PF, Daly MJ, O’Donovan M. Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: the emerging picture and its implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:537–51. doi: 10.1038/nrg3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellinghaus D, Folseraas T, Holm K, Ellinghaus E, Melum E, Balschun T, Laerdahl JK, Shiryaev A, Gotthardt DN, Weismuller TJ, et al. Genome-wide association analysis in primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis identifies risk loci at GPR35 and TCF4. Hepatology. 2013;58:1074–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.25977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundin OH, Broman KW, Chang HH, Vito EC, Stark WJ, Gottsch JD. A common locus for late-onset Fuchs corneal dystrophy maps to 18q21.2-q21.32. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3919–26. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murre C, Bain G, van Dijk MA, Engel I, Furnari BA, Massari ME, Matthews JR, Quong MW, Rivera RR, Stuiver MH. Structure and function of helix-loop-helix proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1218:129–35. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mootha VV, Gong X, Ku HC, Xing C. Association and familial segregation of CTG18.1 trinucleotide repeat expansion of TCF4 gene in Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:33–42. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li YJ, Minear MA, Qin X, Rimmler J, Hauser MA, Allingham RR, Igo RP, Lass JH, Iyengar SK, Klintworth GK, et al. Mitochondrial polymorphism A10398G and Haplogroup I are associated with Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:4577–84. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stamler JF, Roos BR, Wagoner MD, Goins KM, Kitzmann AS, Riley JB, Stone EM, Fingert JH. Confirmation of the association between the TCF4 risk allele and Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy in patients from the Midwestern United States. Ophthalmic Genet. 2013;34:32–4. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2012.726396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuot A, Hewitt AW, Griggs K, Klebe S, Mills R, Jhanji V, Craig JE, Sharma S, Burdon KP. Association of TCF4 and CLU polymorphisms with Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy and implication of CLU and TGFBI proteins in the disease process. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:632–8. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nanda GG, Padhy B, Samal S, Das S, Alone DP. Genetic association of TCF4 intronic polymorphisms, CTG18.1 and rs17089887 with Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy in Indian population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:7674. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li D, Zhou M, Peng X, Sun H. Homocysteine, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism, and risk of retinal vein occlusion: an updated meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou M, Wang W, Huang W, Zhang X. Trabeculectomy with versus without releasable sutures for glaucoma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Igo RJ, Kopplin LJ, Joseph P, Truitt B, Fondran J, Bardenstein D, Aldave AJ, Croasdale CR, Price MO, Rosenwasser M, et al. Differing roles for TCF4 and COL8A2 in central corneal thickness and fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li YJ, Minear MA, Rimmler J, Zhao B, Balajonda E, Hauser MA, Allingham RR, Eghrari AO, Riazuddin SA, Katsanis N, et al. Replication of TCF4 through association and linkage studies in late-onset Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riazuddin SA, McGlumphy EJ, Yeo WS, Wang J, Katsanis N, Gottsch JD. Replication of the TCF4 intronic variant in late-onset Fuchs corneal dystrophy and evidence of independence from the FCD2 locus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2825–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wieben ED, Aleff RA, Eckloff BW, Atkinson EJ, Baheti S, Middha S, Brown WL, Patel SV, Kocher JP, Baratz KH. Comprehensive Assessment of Genetic Variants Within TCF4 in Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:6101–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forrest MP, Hill MJ, Quantock AJ, Martin-Rendon E, Blake DJ. The emerging roles of TCF4 in disease and development. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:322–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackey DA, Warrington NM, Hewitt AW, Oates SK, Yazar S, Soloshenko A, Crawford GJ, Mountain JA, Pennell CE. Role of the TCF4 gene intronic variant in normal variation of corneal endothelium. Cornea. 2012;31:162–6. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318226155f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riazuddin SA, Vasanth S, Katsanis N, Gottsch JD. Mutations in AGBL1 cause dominant late-onset Fuchs corneal dystrophy and alter protein-protein interaction with TCF4. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93:758–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riazuddin SA, Zaghloul NA, Al-Saif A, Davey L, Diplas BH, Meadows DN, Eghrari AO, Minear MA, Li YJ, Klintworth GK, et al. Missense mutations in TCF8 cause late-onset Fuchs corneal dystrophy and interact with FCD4 on chromosome 9p. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wieben ED, Aleff RA, Tosakulwong N, Butz ML, Highsmith WE, Edwards AO, Baratz KH. A common trinucleotide repeat expansion within the transcription factor 4 (TCF4, E2-2) gene predicts Fuchs corneal dystrophy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xing C, Gong X, Hussain I, Khor CC, Tan DT, Aung T, Mehta JS, Vithana EN, Mootha VV. Trans-ethnic Replication of Association of CTG18.1 Repeat Expansion of TCF4 Gene with Fuchs Corneal Dystrophy in Chinese Implies Common Causal Variant. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:7073. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thalamuthu A, Khor CC, Venkataraman D, Koh LW, Tan DT, Aung T, Mehta JS, Vithana EN. Association of TCF4 gene polymorphisms with Fuchs’ corneal dystrophy in the Chinese. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:5573–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang KJ, Jhanji V, Chen J, Law RW, Leung AT, Zhang M, Wang N, Pang CP, Yam GH. Association of transcription factor 4 (TCF4) and protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type G (PTPRG) with corneal dystrophies in southern Chinese. Ophthalmic Genet. 2014;35:138–41. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2013.804098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu L, Zhuang W, Wang C, Chen Z, Wu XT, Zhou Y. Interleukin-8 -251 A/T gene polymorphism and gastric cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Cytokine. 2010;50:328–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu K, Jiang B, Hu R, Yang Y, Miao M, Li Y, Liu Z. The CXCL12 G801A Polymorphism Is Associated with Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright AF, Dhillon B. Major progress in Fuchs’s corneal dystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1072–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1007495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]