Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to describe the incidence, management, and outcomes of mesenteric artery complications (MACs) during angioplasty and stent placement (MAS) for chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI).

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical data of 156 patients treated with 173 MAS for CMI (1998–2010). MACs were defined as procedure-related mesenteric artery dissection, stent dislodgement, embolization, thrombosis, or perforation. End points were procedure-related morbidity and death.

Results

There were 113 women and 43 men (mean age, 73 ± 14 years). Eleven patients (7%) developed 14 MACs, including distal mesenteric embolization in six, branch perforation in three, dissection in two, stent dislodgement in two, and stent thrombosis in one. Five patients required adjunctive endovascular procedures, including in two patients each, catheter-directed thrombolysis or aspiration, retrieval of dislodged stents, and placement of additional stents for dissection. Five patients (45%) required conversion to open repair: two required evacuation of mesenteric hematoma, two required mesenteric revascularization, and one required bowel resection. There were four early deaths (2.5%) due to mesenteric embolization or myocardial infarction in two patients each. Patients with MACs had higher rates of mortality (18% vs 1.5%) and morbidity (64% vs 19%; P <.05) and a longer hospital length of stay (6.3 ± 4.2 vs 1.6 ± 1.2 days) than those without MACs. Periprocedural use of antiplatelet therapy was associated with lower risk of distal embolization or vessel thrombosis (odds ratio, 0.2; 95% confidence interval, 0.06–0.90). Patients treated by a large-profile system had a trend toward more MACs (odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.7–26.5; P = .07).

Conclusions

MACs occurred in 7% of patients who underwent MAS for CMI and resulted in higher mortality, morbidity, and longer hospital length of stay. Use of antiplatelet therapy reduced the risk of distal embolization or vessel thrombosis. There was a trend toward more MACs in patients who underwent interventions performed with a large-profile system.

During the past decade, mesenteric artery stenting (MAS) has surpassed open bypass as the most frequently used method of revascularization to treat chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI). Several centers have adopted an endovascular-first approach, relegating open revascularization to patients in whom stenting fails or whose anatomy is unsuitable for it.1 In a recent review of national outcomes, Schemerhorn et al1 reported a sevenfold increase in the number of mesenteric interventions since 1988 and a remarkable reduction in the mortality rate from 15% with open bypass to 4% with endovascular treatment. A recent systematic review of the best available evidence indicates that MAS decreases morbidity and hospital length of stay and has similar mortality and clinical efficacy but results in more restenoses, symptom recurrences, and reinterventions than open bypass.2

Endovascular interventions are potentially associated with risk of access site and arterial complications from catheter and wire manipulation, balloon dilation, and stent placement. In the mesenteric arteries, dissection, thrombosis, embolization, or perforation may result in bowel ischemia or bleeding, necessitating additional “bail-out” maneuvers, including conversion to open repair. Most important, these complications can be fatal or result in significant morbidity and prolonged hospitalization if not recognized immediately. This study describes the incidence, management, and outcomes of mesenteric artery complications (MACs) during mesenteric angioplasty or stenting for CMI.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The clinical data of all consecutive patients treated with an index MAS procedure for atherosclerotic CMI by a multidisciplinary group of vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists between 1998 and 2010 were entered into an institutional database (1998–2010). CMI was diagnosed in patients with symptom (any or all of abdominal pain, postprandial abdominal pain, “food fear,” weight loss) duration >2 weeks and evidence from conventional angiography of high-grade stenosis or occlusion of the mesenteric arteries. Patients with acute or acute-on-CMI, vasculitides, median arcuate ligament syndrome, or those who had reinterventions for failed mesenteric interventions were excluded from the study.

MACs were defined as anatomic abnormalities that resulted from angioplasty and stent placement, such as dissection, embolization, thrombosis, perforation, and stent dislodgement. Most MACs were identified immediately, but we included in the analysis patients with lesions diagnosed after the procedure because of symptoms that prompted conventional angiography, computed tomography angiography (CTA), or abdominal exploration. Patients with asymptomatic MACs that were not identified by completion angiography were not included in the review.

Lesion characteristics (length, diameter, and severity of calcification) and degree of angulation of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) were analyzed in the preprocedural CTA whenever possible. The severity of calcification was graded as mild (minimal or trivial), moderate (<66% of vessel diameter), or severe (>66% of the vessel diameter). Demographics, clinical characteristics, imaging, and operative data were obtained from the medical records. The early perioperative period was defined as the first 30 days or within the hospital stay if >30 days. Patient morbidity was defined as a medical or surgical complication after the procedure that was caused by MAS. Patient morbidity was analyzed to determine its relationship to the MAC.

Rescue treatment for MACs was individualized at the discretion of the treating physician. Clinical observation was indicated for small lesions that were not considered to be flow limiting and were not associated with thrombus, bowel ischemia, or active bleeding. Adjunctive endovascular interventions (angioplasty, stent placement, catheter-directed thrombolysis or thrombus aspiration, and retrieval of dislodged stents) or conversion to exploratory laparotomy, with or without arterial repair, was needed in patients with significant lesions.

Technical success was defined by residual stenosis <30% by completion angiography. Residual stenosis typically resulted from a recalcitrant lesion or dissection, or both. Antiplatelet therapy included aspirin before the procedure, clopidogrel for 4 to 8 weeks after the procedure, and aspirin thereafter. All patients received intravenous heparin anticoagulation (80–100 U/kg) at the time of mesenteric intervention.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) reporting standards.3 Primary end points were procedure-related morbidity and mortality. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify clinical, anatomic, and procedural factors associated with MACs. Results are reported as median ± standard deviation, percentages, or odds ratio (OR) with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact test was used for analysis of categoric variables. Differences between means were tested with two-sided t-test, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, or the Mann-Whitney test. A value of P < .05 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

The study evaluated 113 women and 43 men (mean age, 72 ± 13 years). The most common presenting symptom (Table I) was abdominal pain, 147 (94%); weight loss, 126 (80%); “food fear,” 82 (52%); nausea or vomiting, or both, 41 (26%); and diarrhea, 38 (24%). A total of 173 mesenteric vessels were treated (Table II) by angioplasty alone (22 SMA, 10 celiac axis [CA], and three inferior mesenteric arteries [IMA]) or angioplasty and stent placement (94 SMA, 42 CA, and two IMA).

Table I.

Demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, and medical therapy in 156 patients treated by mesenteric angioplasty and stent placement for chronic mesenteric ischemia

| Variablesa | All patients | Femoral

|

P | Brachial

|

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large profile | Small profile | Large profile | Small profile | ||||

| Patients | 156 (100) | 67 (43) | 39 (25) | 14 (9) | 36 (23) | ||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age | 73 14 | 73 ± 13 | 73 ± 14 | .7 | 73 ± 13 | 75 ± 10 | .07 |

| Female | 113 (72) | 47 (70) | 31 (79) | .6 | 8 (57) | 27 (75) | .6 |

| Male | 43 (27) | 20 (30) | 8 (20) | .4 | 6 (43) | 9 (25) | .4 |

| Clinical presentation | |||||||

| Abdominal pain | 147 (94) | 64 (95) | 36 (92) | >.99 | 14 (100) | 33 (92) | .8 |

| Weight loss | 126 (80) | 53 (79) | 33 (85) | .8 | 10 (71) | 30 (83) | .7 |

| Food fear | 82 (52) | 41 (61) | 13 (33) | .1 | 5 (36) | 23 (64) | .3 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 41 (26) | 24 (36) | 8 (20) | .2 | 3 (21) | 6 (17) | .7 |

| Diarrhea | 38 (24) | 24 (36) | 7 (18) | .1 | 2 (14) | 5 (14) | >.99 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||||||

| Hypertension | 134 (85) | 53 (79) | 35 (90) | .6 | 14 (100) | 32 (89) | .8 |

| Dyslipidemia | 103 (66) | 38 (57) | 28 (72) | .4 | 10 (71) | 27 (75) | >.99 |

| Coronary artery disease | 100 (64) | 42 (63) | 22 (56) | .8 | 10 (71) | 26 (72) | >.99 |

| Cigarette smoker | 89 (57) | 46 (69) | 22 (56) | .6 | 6 (43) | 15 (42) | >.99 |

| Myocardial infarction | 56 (36) | 4 (6) | 13 (33) | .002 | 5 (36) | 14 (39) | >.99 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 67 (43) | 28 (42) | 20 (51) | .5 | 6 (43) | 13 (36) | >.99 |

| COPD | 47 (30) | 18 (27) | 14 (36) | .4 | 7 (50) | 8 (22) | .2 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 49 (31) | 27 (40) | 10 (26) | .3 | 4 (29) | 8 (22) | .3 |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 39 (25) | 21 (31) | 8 (20) | .4 | 4 (29) | 6 (17) | .5 |

| Baseline creatinine, mg/dL | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | .7 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | .8 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 36 (23) | 18 (27) | 9 (23) | .8 | 1 (7) | 8 (22) | .3 |

| Congestive heart failure | 30 (19) | 15 (22) | 5 (13) | .3 | 4 (29) | 6 (17) | .5 |

| SVS score sum | 9.7 ± 6.0 | 9.5 ± 6.4 | 11.6 ± 6.0 | .07 | 7.6 ± 4.2 | 8.9 ± 5.0 | .4 |

| Preadmission medications | |||||||

| Any antiplatelet therapy | 98 (62) | 40 (60) | 27 (69) | .6 | 5 (36) | 26 (72) | .2 |

| ASA | 89 (57) | 37 (55) | 23 (59) | .8 | 4 (29) | 25 (69) | .1 |

| Clopidogrel | 21 (13) | 7 (10) | 6 (15) | .5 | 2 (14) | 6 (17) | >.99 |

| ASA + clopidogrel | 12 (8) | 2 (3) | 4 (10) | .2 | 1 (7) | 5 (14) | >.99 |

| Warfarin | 20 (13) | 13 (19) | 2 (5) | .08 | 0 (0) | 5 (14) | .2 |

| Antiplatelet + anticoagulation | 32 (20) | 14 (21) | 5 (13) | .4 | 1 (7) | 12 (33) | .1 |

| Statins | 67 (43) | 18 (27) | 19 (49) | .1 | 7 (50) | 23 (64) | .6 |

| β-blockers | 70 (45) | 24 (36) | 14 (36) | >.99 | 8 (57) | 24 (67) | .7 |

| ACE inhibitor | 73 (46) | 25 (37)b | 22 (56)b | .2 | 8 (57) | 18 (50) | .8 |

| Diuretic | 50 (32) | 19 (28) | 16 (41) | .3 | 7 (50) | 8 (22) | .2 |

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Categoric variables are expressed as number (percentage) and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation.

Groups associated with the lower P value.

Table II.

Procedural details in 156 patients treated by mesenteric angioplasty and stent placement for chronic mesenteric ischemia

| Variables | Mean ± SD, or patients/vessels No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Target vessela | |

| Length, mm | 15 ± 4.4 |

| Diameter, mm | 5.8 ± 0.8 |

| Superior mesenteric artery | 116 (67) |

| Celiac artery | 52 (30) |

| Inferior mesenteric artery | 5 (3) |

| One vessel treated | 125 (72) |

| Two vessels treated | 24 (28) |

| Calcificationb | |

| Absent/irrelevant | 23 (13) |

| Moderate | 19 (11) |

| Severe | 56 (32) |

| Technical data | |

| PTA with stenting | 128/138 (80) |

| PTA alone | 28/35 (20) |

| Stent/balloon, mm | |

| Diameter | 5.8 ± 0.6 |

| Length | 20.8 ± 8 |

| Stent type | |

| Balloon-expandable | 125/134 |

| Self-expandable | 3/4 (2) |

| Embolic protection device | 14 (9) |

| Femoral approach | 106 (68) |

| Brachial approach | 50 (33) |

| Profile | |

| Large, 0.035-inch | 81 (52) |

| Small, <0.018-inch | 75 (48) |

| Femoral | |

| + large profile | 67 (43) |

| + small profile | 39 (25) |

| Brachial | |

| + small profile | 36 (23) |

| + large profile | 14 (9) |

| Residual stenosis | |

| Absent | 132 (85) |

| <30% | 16 (10) |

| >30% | 8 (5) |

PTA, Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; SD, standard deviation.

Denominator is the number of vessels (n = 173).

For only 88 patients/98 vessels was computed tomography/computed tomography angiography imaging available.

Femoral access was used in 106 patients (68%) and brachial access in 50 (32%), including 34 patients who underwent primary exposure and repair of the brachial artery under local anesthesia. A large-profile system (0.035-inch wire) was used in 81 patients (52%) to treat 94 vessels, whereas interventions in 75 vessels (48%) were with a small-profile system (0.014- or 0.018-inch). Of 106 patients treated by the transfemoral approach, 67 (64%) had interventions with a large-profile system vs 39 (37%; P = .01) with a small-profile system, whereas of 50 transbrachial interventions, 36 (72%) were performed with small-profile systems vs 14 (28%; P = .02) with a large-profile system. Balloon-expandable stents were used to treat 134 lesions in 125 patients (98%), and self-expandable stents were used to treat four lesions in three patients. Technical success was achieved in 166 (96%) of the 173 vessels. Completion angiography demonstrated no residual stenosis in 147 vessels, residual stenosis <30% in 19, and residual stenosis >30% in seven.

MACs

Eleven patients (7%) developed 14 MACs (Table III, A and B). The incidence of MAC was 10% for SMA interventions (12 of 117), 2% for CA (one of 52), 20% for IMA (one of five), 9% for angioplasty alone (three of 35), and 8% for MAS (11 of 139).

Table III.

A, Demographics, lesion characteristics, and procedural details of 11 patients treated by angioplasty and stent placement for chronic mesenteric ischemia

| Pt | Age | Sex | Medical therapy | Lesion characteristics | Procedure details

|

Mesenteric artery complication | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approach | Multiple exchanges | GW profile and type | Stent | ||||||

| 1 | 73 | F | ASA | SMA occlusion, 15-mm length, severe calcification, SMA angle 21° | Femoral | Yes | 0.035-inch stiff hydrophilic GW, stiff J-tip braided GW | 5- × 12-mm balloon | Embolization |

| 2 | 85 | F | ASA | CA high-grade stenosis, 14-mm length, severe calcification, SMA angle 30° | Femoral | No | 0.035-inch stiff angled hydrophilic GW, 0.014-inch stiff braided GW | 6 × 17 mm | Embolization |

| 3 | 66 | F | None | SMA high-grade stenosis, 22-mm length, severe calcification, SMA angle 26° | Femoral | No | 0.035-inch hydrophilic GW, 0.035-inch straight braided GW | 6 × 27 mm | Dissection, embolization |

| 4 | 84 | M | CLOP | SMA high-grade stenosis, 35-mm length, mild calcification | Femoral | Yes | 0.035-inch angled hydrophilic GW | 6 × 15 mm | Stent thrombosis, embolization |

| 5 | 69 | F | None | SMA high-grade stenosis, 15-mm length, severe calcification, SMA angle 66° | Femoral | Yes | 0.035-inch stiff hydrophilic GW, straight braided GW | 6 × 27 mm (hand mounted) | Stent dislodgement, embolization |

| 6 | 68, F | F | CLOP | SMA high-grade stenosis, 14-mm length, moderate calcification, SMA angle 15° | Femoral | Yes | 0.035-inch stiff angled GW inch system | 5 × 17 mm | Perforation |

| 7 | 62, F | F | None | IMA high-grade stenosis, 9-mm length, severe calcification, IMA angle 32° | Femoral | Yes | 0.035-inch J-tip braided GW, 0.018-inch straight-tip braided GW | 5- × 20-mm balloon | Embolization |

| 8 | 58 | F | None | SMA high-grade stenosis, 15-mm length, moderate calcification, SMA angle 21° | Brachial | No | 0.035-inch stiff angled hydrophilic GW | 4- × 18-mm balloon | Perforation |

| 9 | 83 | F | CLOP, ASA | SMA high-grade stenosis, 23-mm length, severe calcification; SMA angle 36° | Femoral | Yes | 0.035-inch straight braided GW | 6 × 27 mm (hand mounted) | Stent dislodgement |

| 10 | 77 | M | ASA | SMA occlusion, 50-mm length, moderate calcification, SMA angle 48° | Brachial | No | 0.035-inch straight braided GW | 6 × 17 mm | Dissection |

| 11 | 80 | F | CLOP | SMA high-grade stenosis, 22-mm length, mild calcification, SMA angle 23° | Brachial | No | 0.014-inch hydrophilic straight GW | 6 × 18 mm | Perforation |

ASA, Acetylsalicylic acid; CA, celiac axis; CLOP, clopidogrel; F, female; GW, guidewire; IMA, inferior mesenteric artery; M, male; SMA, superior mesenteric artery.

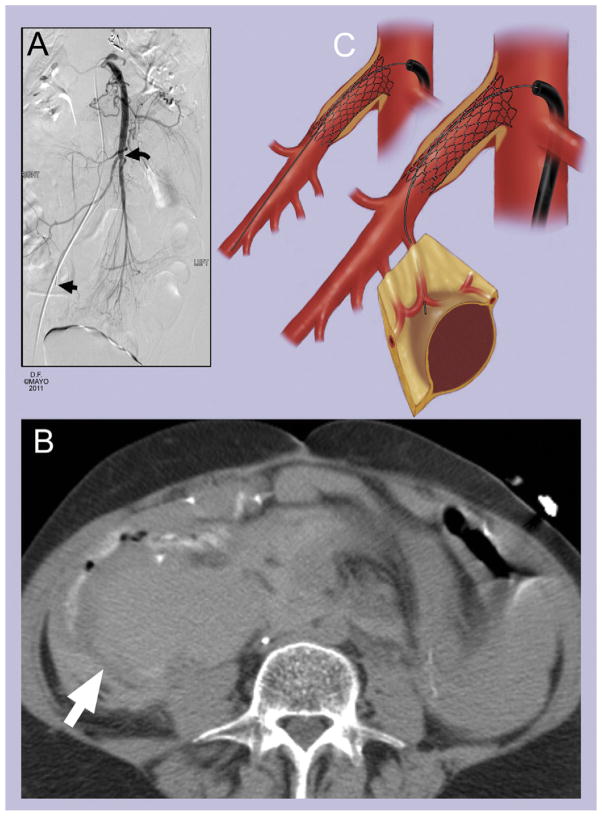

Six patients had embolization to distal branches (Fig 1), which occurred along with proximal flow-limiting dissection, stent dislodgement, or stent thrombosis in one patient each. Three patients developed jejunal branch perforations, including one patient with a small contained perforation associated with a small-profile system and two patients with large mesenteric hematomas (Fig 2) associated with multiple exchanges of large-profile guidewires. One patient had isolated SMA dissection and another had stent dislodgement without distal embolization. The two patients with stent dislodgement had hand-mounted stents placed through a transfemoral approach, with severe SMA angulation.

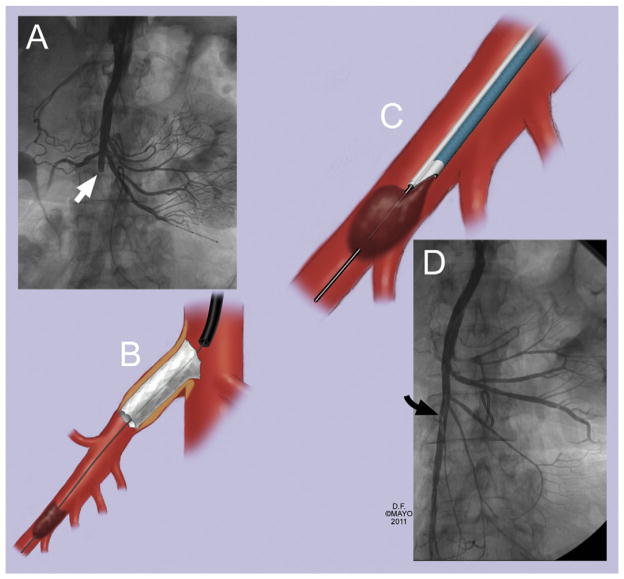

Fig 1.

An 85-year-old woman presented with chronic abdominal pain and weight loss for 3 months and occlusion of the celiac axis and superior mesenteric artery (SMA). A and B, Successful recanalization of an occluded SMA was complicated by distal embolization (white arrow), which was (C) successfully salvaged by catheter-directed thrombolysis and catheter aspiration with an Export aspiration catheter (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minn) over a 0.014-inch wire. D, Completion angiography showed widely patent SMA with a small, non–flow-limiting dissection flap (black arrow).

Fig 2.

A, Mesenteric artery stenting performed through the femoral approach was complicated by (B) side branch perforation (white arrow). The correct location to position the guidewire should be ideally in the main trunk of the superior mesenteric artery (A, black curved arrow and C) and not within jejunal branches (A, straight black arrow and C).

Rescue treatment

The complication was recognized immediately in eight patients (73%), including five with distal embolization and three with dissection, stent dislodgement, or contained perforation, respectively. The small, contained branch perforation spontaneously sealed on follow-up angiography performed during the procedure and did not require treatment. The large mesenteric hematomas were diagnosed in two patients at 12 and 27 hours after the procedure because of significant abdominal pain and decreasing hemoglobin, which prompted CTA (Fig 2). One patient presented with abdominal pain and bowel ischemia at 24 hours after stent placement due to distal embolization, which was not recognized on completion angiography.

Five patients underwent adjunctive endovascular interventions. Two patients underwent placement of a second stent, which successfully resolved dissection flaps. Two dislodged stents were retrieved using a snare and deployed in a neutral position within the iliac artery, followed by successful repeat stenting of the SMA. Two patients with distal embolization underwent catheter-directed thrombolysis and thrombus aspiration (Fig 1).

Five patients required conversion to open surgical repair, including after failed endovascular treatment in one. The two patients with large mesenteric hematomas were treated by abdominal exploration, evacuation of the hematoma, and hemostasis. One patient with stent thrombosis underwent removal of the stent, thromboendarterectomy, and patch angioplasty. One patient with sigmoid ischemia from distal embolism required segmental colectomy and mesenteric bypass, and another patient with distal embolism required bowel resection without revascularization.

Mortality

There were four procedure-related deaths (2.5%). Early mortality was 18% (two of 11) in patients with MACs compared with 1.4% in those who had no MACs (two of 145; P < .001). Two patients with distal embolization died of multiorgan system failure (MOSF) 11 and 58 days later, despite abdominal exploration and revascularization. Two patients with pre-existing ischemic cardiomyopathy died of myocardial infarction. Multivariate analysis found no independent predictors for death.

Morbidity

Thirty-four patients (15%) presented with 46 postprocedural complications (Table IV). Seven patients (64%) with MACs developed additional complications compared with 28 (19%) of those who did not have MACs during the intervention (P < .01). The most common complications were access-related problems in 11 patients, renal insufficiency in seven (dialysis-dependent in one), myocardial infarction in four, gastrointestinal bleeding in two, and lower extremity embolization in one. Eight access-site complications occurred in six patients (6%) who had transfemoral interventions, including five pseudoaneurysms, two infections, and one nerve injury. Three patients required surgical evacuation of hematoma. Eight access-site problems developed among five patients treated by a transbrachial approach (10%), all occurring among 16 patients (31%) who had percutaneous approach. Access-related problems included pseudoaneurysm in three patients and arterial thrombosis, arteriovenous fistula, or swelling in one each. Of these, three patients underwent hematomas and repair of pseudoaneurysms, including two patients with temporary neuropraxia of the median nerve.

Table IV.

B, Treatment and outcomes in 11 patients who developed mesenteric artery complications during angioplasty and stent placement for chronic mesenteric ischemia

| Pt | Mesenteric artery complication | Rescue treatment

|

Early outcome

|

Late outcome

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing | Intervention | Resolution | Post-MAS complication | LOS (days) | Follow-up (months) | Status | ||

| 1 | Embolization | Immediate | Ao-SMA bypass, bowel resection | Yes | Acute renal failure | 18 | None | . . . |

| 2 | Embolization | Immediate | t-PA + catheter aspiration | Yes | None | 5 | None | . . . |

| 3 | Dissection, embolization | Immediate | Stent placement | Yes | Acute renal failure | 7 | 23 | Restenosis |

| 4 | Stent thrombosis, embolization | Immediate | Thromboendarterectomy, stent removal, patch angioplasty | Yes | Acute renal failure | 21 | 3 | Patent |

| 5 | Stent dislodgement, embolization | Immediate | Local t-PA, catheter aspiration, re-stenting | No | Bowel resection, MOSF, death | 11 | . . . | . . . |

| 6 | Perforation | Delayed | Surgical evacuation, ligation bleeding branch | Yes | No further complications | 16 | 4 | Patent |

| 7 | Embolization | Delayed | Bowel resection | No | MOSF, death | 58 | . . . | |

| 8 | Perforation | Delayed | Surgical evacuation, ligation bleeding branch | Yes | No further complications | 12 | 21 | Patent |

| 9 | Stent dislodgement | Immediate | Restenting | Yes | No further complications | 2 | None | . . . |

| 10 | Dissection | Immediate | t-PA + stenting | Yes | Acute renal failure | 4 | 1 | Patent |

| 11 | Perforation | Immediate | Sealed spontaneously on follow-up angiography | Yes | No further complications | 2 | 3 | Patent |

Ao, Aorta; LOS, length of stay; MOSF, multiorgan system failure; SMA, superior mesenteric artery; t-PA, tissue, plasminogen activator.

Hospital length of stay was significantly longer (P < .05) among patients who developed MACs (6.3 ± 4.2 vs 1.6 ± 1.2 days) and among those who had postprocedural complications (12 ± 5 vs 1 ± 2 days). Factors associated with higher rates of postprocedural complications by univariate analysis (OR and 95% CI) were female sex, 3.4 (1.3–9.0; P = .01); diabetes, 3.0 (0.97–9.2; P = .06); renal insufficiency, 2.9 (0.9–9.1; P = .07); chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2.9 (0.9–8.8; P = .07); and MACs, 3.8 (0.8–18.4; P = .1). Female sex was the only independent factor associated with a higher morbidity rate (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.1–8.8; P = .03), whereas the presence of MAC was associated with a trend toward more complications (OR, 4.09; 95% CI, 0.8–70.0; P = .2).

Predictors of MACs

Patients whose interventions were performed with a large-profile system had a 12% rate of MACs compared with 4% in those who underwent procedures with a small-profile system (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–26.5; P = .07). Patients treated by a large-profile system sustained more dissections, embolizations, and perforations, but differences did not reach statistical significance (Table IV). MACs occurred in eight patients (8.4%) treated through a femoral approach (seven of 68 for large-profile vs one of 39 for small-profile system; P = .09) and in three (6%) who had transbrachial procedures (two of 14 for large-profile vs one of 36 for small-profile system; P = .5). Use of antiplatelet therapy was associated with lower rates of distal embolization or vessel thrombosis (OR, 0.2; 95% CI, 0.06–0.90; P = .03) by univariate model. However, there were no independent factors for MACs by multivariate analysis.

DISCUSSION

Endovascular treatment has several short-term advantages compared with open surgical bypass in patients with CMI.1,2,4–12 However, despite its minimally invasive approach, angioplasty and stent placement carries a predictable risk of morbidity and mortality. This study indicates that the occurrence of anatomic complications during catheter manipulations and stent placement significantly increases the risk of death (18%) and morbidity (54%) and also prolongs hospitalization.

Mortality rates are 0% to 10% in contemporary reports of MAS.6,13–17 The most common causes of death in these reports are myocardial infarction and MOSF, which is often caused by bowel ischemia from distal embolization, dissection, or stent thrombosis. The Cleveland Clinic group reported that three of their five deaths (60%) resulted from distal embolism. Similar to that report, two of our four deaths (50%) occurred in patients with distal embolization resulting in bowel ischemia and MOSF. Therefore, procedure planning, case selection, and use of meticulous technique are likely to be important factors that will reduce rates of MACs and therefore have a positive effect on morbidity and mortality after these interventions.

We attempted to identify that factors that predisposed patients to develop MAC. Unfortunately, because of the retrospective design and small number of patients, we were unable to determine the effect of operator experience, learning curve, and technical difficulties encountered during the procedure. However, we found a trend toward more MACs among patients treated by larger-profile devices, which makes intuitive sense given that these devices require larger delivery systems and stiffer guidewires to provide enough support. Some of the complications noted in the study, such as dissections and branch perforations, may occur more frequently in patients treated by larger-profile devices, particularly if multiple exchanges are necessary to overcome acute angulation. Another important observation is to visualize the tip of the guidewire in the main trunk of the SMA instead of within a small jejunal branch, which is more prone to dissection or perforation.

We also noted that the risk of embolization and thrombosis was reduced by antiplatelet therapy started before the intervention. Finally, stent dislodgement, which occurred in two patients treated by hand-mounted stents, has not been a problem since premounted stents became available. However, this complication can occur with covered stents or in patients with recalcitrant lesions that are prone to “watermelon seed” the stent during deployment.

Endovascular technology evolved during the last decade with the introduction of a wide range of smaller-profile devices, rapid-exchange systems, hydrophilic sheaths, guide catheters, premounted stents, and embolic protection devices. Although we were not able to evaluate the effect of each one of these technologic improvements, there are important lessons from our initial experience.

The ideal approach (femoral vs brachial) is controversial and somewhat dependent on the ability of the treating physician to surgically repair the brachial artery. Nonetheless, we found that the brachial approach offers excellent access in patients with acute angles at the vessel origin, occlusions, or long lesions. The mesenteric arteries are easier to catheterize from above, and a more favorable angle decreases the need to use stiff guidewires and avoids multiple catheter exchanges that may be necessary because of access difficulties that are encountered from the femoral approach. Nevertheless, brachial punctures are more prone to access-related complications, including potentially disabling neuropraxia of the median nerve, as noted in this study. Therefore, we have more often used surgical exposure and repair of the brachial artery under local anesthesia. Another alternative to the brachial approach, which has been widely used for cardiac interventions, is radial artery access.

The use a small-profile (0.014- or 0.018-inch) system has several advantages, including smaller delivery system, rapid exchange, and potentially less traumatic guidewires and stents. In general, guidewires with a braided or platinum tip are less traumatic than those with hydrophilic tips, but the latter are ideal to cross occlusions or difficult stenosis. The tip of the guidewire should be visualized to avoid inadvertent perforation or dissections. Finally, we have used balloon-expandable stents in nearly all cases because of the advantages of precise deployment and greater radial force, key elements when treating ostial lesions such as those involving the mesenteric arteries. Nonetheless, self-expandable stents are useful to treat those longer lesions that extend over tortuous or angulated segments of the mesenteric vessels.

The use of embolic protection devices during MAS remains controversial. However, these devices should be considered as part of the armamentarium in selected cases, given that distal embolization is an important cause of death in many reports. We previously reviewed the incidence of distal embolization in 85 consecutive patients treated by SMA stent placement without embolic protection and found angiographic confirmation of emboli in 8% of patients.18 In that report, distal embolization resulted in the only two procedure-related deaths in the entire cohort. Factors associated with higher rates of distal embolization were mesenteric occlusion, severe calcification, and lesion length >30 mm.18 Since that 2009 report, we have started using embolic protection devices selectively in patients with at least one of the anatomic characteristics mentioned above. In a recent review of our first 14 patients so treated, nine (65%) had macroscopic debris in the filter basket, and none had distal embolization on completion angiography, compared with a 5% rate of embolization among 43 patients treated without embolic protection during the same period.19

Although this study is novel because it addressed the incidence, predictive factors, management, and outcomes of MACs, several shortcomings need to be discussed. We were not able to determine the individual factors that affected choice of the technique and device selection or the effect of learning curve. In addition, because angiographic studies were reviewed retrospectively and invasive imaging was not obtained in patients who had an uneventful recovery, our study likely underreported the rates of MACs. Furthermore, the small number of patients with events limits our ability to analyze predictive factors for MACs using a multivariate model.

CONCLUSIONS

MACs occurred in 7% of patients undergoing MAS for CMI and resulted in higher morbidity and mortality rates and a longer hospital stay. The use of larger-profile devices was associated with a trend toward more MACs, whereas the use of antiplatelet therapy during the procedure reduced the risk of distal embolization or vessel thrombosis. Our technique has evolved to where now we prefer to use the brachial approach in patients with an angulated SMA origin, occlusions, or difficult lesions. However, we recognize that brachial punctures are associated with the potential risk of access-related problems, and currently, we frequently perform surgical repair of the puncture site with a small incision. Finally, improvements in patient selection, medical therapy, and endovascular techniques, including the use of smaller-profile systems and selective embolic protection, are likely to reduce rates of MACs.

Table V.

Periprocedural mortality and morbidity among 156 patients treated by mesenteric angioplasty and stent placement for chronic mesenteric ischemia

| Variable | Femoral, No. (%)

|

Brachial, No. (%)

|

Total, No. (%)(N = 156) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large profile (n = 67) | Small profile (n = 39) | Large profile (n = 14) | Small profile (n = 36) | |||

| Mortality | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0)a | 2 (14)a | 1 (2.8) | 4 (2.5) | .08a |

| Any complications | 25 (37)a | 6 (15)a | 4 (28) | 12 (33) | 46 (30) | .05a |

| Cardiac | ||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0)a | 2 (5.6)a | 3 (1.9) | .2a |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | >.99a |

| Respiratory | ||||||

| Intubation >72 hours | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0)a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | >.99a |

| Pneumonia | 0 (0)a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8)a | 1 (0.6) | .3a |

| Renal | ||||||

| Renal failure | 4 (6)a | 1 (2.6) | 1 (7) | 0 (0)a | 6 (3.8) | .3a |

| Dialysis | 1 (1.5)a | 0 (0)a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | >.99a |

| Others | ||||||

| Upper GI bleeding | 1 (1.5) | 1 (2.6)a | 0 (0)a | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | >.99a |

| Limb embolism | 1 (1.5)a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0)a | 1 (1.3) | >.99a |

| Cerebral ischemia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7)a | 0 (0)a | 1 (0.6) | .3a |

| Any access-site complication | 6 (9) | 2 (5.6) | 0 (0)a | 8 (22)a | 16 (10.2) | .2a |

| Hematoma | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0)a | 1 (2.8)a | 1 (0.6) | .5a |

| Thrombosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0)a | 1 (2.8)a | 1 (0.6) | .5a |

| Arteriovenous fistula | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0)a | 1 (2.8)a | 1 (0.6) | .5a |

| Pseudoaneurysm | 4 (6)a | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0)a | 2 (5.6) | 7 (4.5) | >.99a |

| Nerve injury | 0 (0)a | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.6)a | 3 (1.9) | .1a |

| Wound infection | 2 (3)a | 0 (0)a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | .5a |

| Arm swelling | 0 (0)a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8)a | 1 (0.6) | .5a |

| Any MAC | 9 (13.4)a | 2 (5.6) | 2 (14) | 1 (2.8)a | 14 (9) | .2a |

| Mesenteric embolism | 5 (7.5)a | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0)a | 6 (3.8) | .2a |

| Vessel perforation | 0 (0)a | 1 (2.6) | 1 (7)a | 1 (2.8) | 3 (1.9) | .5a |

| Dissection | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0)a | 1 (7)a | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | .3a |

| Dislodging of stent | 2 (3)a | 0 (0)a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | .5a |

| Stent thrombosis | 1 (1.5)a | 0 (0)a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | >.99a |

GI, Gastrointestinal; MAC, mesenteric artery complication.

Indicates variables compared and the P value.

Footnotes

Competition of interest: Dr Oderich has a consultant agreement for Cook Medical Inc.

Presented at the Thirty-ninth Annual Symposium of the Society for Clinical Vascular Surgery, Orlando, Fla, March 16–19, 2011.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a competition of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: GO

Analysis and interpretation: GO, TT, PG, AD, MK, SM, SC, TB

Data collection: GO, TT

Writing the article: GO, TT, PG, AD, MK, SM, SC, TB

Critical revision of the article: GO, TT, PG, AAD, MK, SM, SC, TCB

Final approval of the article: GO, TT, PG, AAD, MK, SM, SC, TB

Statistical analysis: GO, TT, SC

Obtained funding: GO

Overall responsibility: GO

References

- 1.Schermerhorn ML, Giles KA, Hamdan AD, Wyers MC, Pomposelli FB. Mesenteric revascularization: management and outcomes in the United States, 1988–2006. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:341–8. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Petersen AS, Kolkman JJ, Beuk RJ, Huisman AB, Doelman CJ, Geelkerken RH, et al. Open or percutaneous revascularization for chronic splanchnic syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:1309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaikof EL, Fillinger MF, Matsumura JS, Rutherford RB, White GH, Blankensteijn JD, et al. Identifying and grading factors that modify the outcome of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:1061–6. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.123991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aksu C, Demirpolat G, Oran I, Demirpolat G, Parildar M, Memis A. Stent implantation in chronic mesenteric ischemia. Acta Radiol. 2009;50:610–6. doi: 10.1080/02841850902953873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkins MD, Kwolek CJ, LaMuraglia GM, Brewster DC, Chung TK, Cambria RP. Surgical revascularization versus endovascular therapy for chronic mesenteric ischemia: a comparative experience. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:1162–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown DJ, Schermerhorn ML, Powell RJ, Fillinger MF, Rzucidlo EM, Walsh DB, et al. Mesenteric stenting for chronic mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbons CP, Roberts DE. Endovascular treatment of chronic arterial mesenteric ischemia: a changing perspective? Semin Vasc Surg. 2010;23:47–53. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oderich GS, Bower TC, Sullivan TM, Bjarnason H, Cha S, Gloviczki P. Open versus endovascular revascularization for chronic mesenteric ischemia: risk-stratified outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1472–9. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies RS, Wall ML, Silverman SH, Simms MH, Vohra RK, Bradbury AW, et al. Surgical versus endovascular reconstruction for chronic mesenteric ischemia: a contemporary UK series. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;43:157–64. doi: 10.1177/1538574408328665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penugonda N, Gardi D, Schreiber T. Percutaneous intervention of superior mesenteric artery stenosis in elderly patients. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:232–5. doi: 10.1002/clc.20446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaefer PJ, Schaefer FK, Hinrichsen H, Jahnke T, Charalambous N, Heller M, et al. Stent placement with the monorail technique for treatment of mesenteric artery stenosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:637–43. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000208983.39430.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kougias P, Huynh TT, Lin PH. Clinical outcomes of mesenteric artery stenting versus surgical revascularization in chronic mesenteric ischemia. Int Angiol. 2009;28:132–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biebl M, Oldenburg WA, Paz-Fumagalli R, McKinney JM, Hakaim AG. Surgical and interventional visceral revascularization for the treatment of chronic mesenteric ischemia–when to prefer which? World J Surg. 2007;31:562–8. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maspes F, Mazzetti di Pietralata G, Gandini R, Innocenzi L, Lupattelli L, Barzi F, et al. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty in the treatment of chronic mesenteric ischemia: results and 3 years of follow-up in 23 patients. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:358–63. doi: 10.1007/s002619900361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto AH, Angle JF, Spinosa DJ, Hagspiel KD, Cage DL, Leung DA, et al. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting in the treatment of chronic mesenteric ischemia: results and longterm followup. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194(1 Suppl):S22–31. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharafuddin MJ, Olson CH, Sun S, Kresowik TF, Corson JD. Endovascular treatment of celiac and mesenteric arteries stenoses: applications and results. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:692–8. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)01030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheeran SR, Murphy TP, Khwaja A, Sussman SK, Hallisey MJ. Stent placement for treatment of mesenteric artery stenoses or occlusions. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:861–7. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(99)70128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oderich GS, Macedo TA, Malgor RD, Bower TC, Vritiska T, Duncan AA, et al. Natural history and predictors of mesenteric artery in-stent restenosis in patients with mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tallarita T, Gustavo S, Oderich MD, Gloviczki P, Audra A, Duncan MD, et al. Embolic protection in mesenteric artery stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2011 [Google Scholar]