Abstract

DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair by homologous recombination (HR) requires 3′ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) generation by 5′ DNA-end resection. During meiosis, yeast Sae2 cooperates with the nuclease Mre11 to remove covalently bound Spo11 from DSB termini, allowing resection and HR to ensue. Mitotic roles of Sae2 and Mre11 nuclease have remained enigmatic, however, since cells lacking these display modest resection defects but marked DNA damage hypersensitivities. By combining classic genetic suppressor screening with high-throughput DNA sequencing, we identify Mre11 mutations that strongly suppress DNA damage sensitivities of sae2Δ cells. By assessing the impacts of these mutations at the cellular, biochemical and structural levels, we propose that, in addition to promoting resection, a crucial role for Sae2 and Mre11 nuclease activity in mitotic DSB repair is to facilitate the removal of Mre11 from ssDNA associated with DSB ends. Thus, without Sae2 or Mre11 nuclease activity, Mre11 bound to partly processed DSBs impairs strand invasion and HR.

Keywords: Mre11, Sae2, suppressor screening, synthetic viability, whole-genome sequencing

Introduction

The DSB is the most cytotoxic form of DNA damage, with ineffective DSB repair leading to mutations, chromosomal rearrangements and genome instability that can yield cancer, neurodegenerative disease, immunodeficiency and/or infertility (Jackson & Bartek, 2009). DSBs arise from ionising radiation and radiomimetic drugs and are generated when replication forks encounter single-stranded DNA breaks or other DNA lesions, including DNA alkylation adducts and sites of abortive topoisomerase activity. DSBs are also physiological intermediates in meiotic recombination, being introduced during meiotic prophase I by the topoisomerase II-type enzyme Spo11 that becomes covalently linked to the 5′ end of each side of the DSB (Keeney et al, 1997). The two main DSB repair pathways are non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (Lisby et al, 2004; Symington & Gautier, 2011). In NHEJ, DNA ends need little or no processing before being ligated (Daley et al, 2005). By contrast, HR requires DNA-end resection, a process involving degradation of the 5′ ends of the break, yielding 3′ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) tails that mediate HR via pairing with and invading the sister chromatid, which provides the repair template.

Reflecting the above requirements, cells defective in resection components display HR defects and hypersensitivity to various DNA-damaging agents. This is well illustrated by Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells harbouring defects in the Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 (MRX) complex, which binds and juxtaposes the two ends of a DSB (Williams et al, 2008) and, through Mre11 catalytic functions, provides nuclease activities involved in DSB processing (Furuse et al, 1998; Williams et al, 2008; Stracker & Petrini, 2011). Once a clean, partially resected 5′ end has been generated, the enzymes Exo1 and Sgs1/Dna2 are then thought to act, generating extensive ssDNA regions needed for effective HR (Mimitou & Symington, 2008; Zhu et al, 2008). Notably, while Mre11 nuclease activity is essential in meiosis to remove Spo11 and promote 5′ end resection, in mitotic cells, resection is only somewhat delayed in the absence of Mre11 and almost unaffected by mre11-nd (nuclease-dead) mutations (Ivanov et al, 1994; Moreau et al, 1999), indicating the existence of MRX-nuclease-independent routes for ssDNA generation.

Another protein linked to resection is S. cerevisiae Sae2, the functional homolog of human CtIP (Sartori et al, 2007; You et al, 2009). Despite lacking obvious catalytic domains, Sae2 and CtIP have been reported to display endonuclease activity in vitro (Lengsfeld et al, 2007; Makharashvili et al, 2014; Wang et al, 2014), and their functions are tightly regulated by cell cycle- and DNA damage-dependent phosphorylations (Baroni et al, 2004; Huertas et al, 2008; Huertas & Jackson, 2009; Barton et al, 2014). In many ways, Sae2 appears to function together with MRX in DSB repair. For instance, mre11-nd as well as mre11S and rad50S hypomorphic alleles phenocopy SAE2 deletion (sae2Δ) in meiosis, yielding unprocessed Spo11–DNA complexes (Keeney & Kleckner, 1995; Nairz & Klein, 1997; Prinz et al, 1997). Furthermore, recent findings have indicated that Sae2 stimulates Mre11 endonuclease activity to promote resection, particularly at protein-bound DSB ends (Cannavo & Cejka, 2014). Also, both sae2Δ and mre11-nd mutations cause hypersensitivity towards the anti-cancer drug camptothecin (Deng et al, 2005), which yields DSBs that are repaired by HR. Nevertheless, key differences between MRX and Sae2 exist, since sae2Δ leads to persistence of MRX at DNA damage sites (Lisby et al, 2004) and hyperactivation of the MRX-associated Tel1 protein kinase (Usui et al, 2001), the homolog of human ATM, while MRX inactivation abrogates Tel1 function (Fukunaga et al, 2011). These findings, together with sae2Δ and mre11-nd cells displaying only mild resection defects (Clerici et al, 2005), highlight how Sae2 functions in HR cannot be readily explained by it simply cooperating with MRX to enhance resection.

As reported below, by combining classic genetic screening for suppressor mutants with whole-genome sequencing to determine their genotype, we are led to a model that resolves apparent paradoxes regarding Sae2 and MRX functions, namely the fact that while deletion of either SAE2 or MRE11 causes hypersensitivity to DNA-damaging agents, the resection defect of sae2Δ strains is negligible compared to that of mre11Δ cells, and lack of Sae2 causes an increase in Mre11 persistence at DSB ends rather than a loss. Our model invokes Mre11/MRX removal from DNA as a critical step in allowing HR to proceed effectively on a resected DNA template.

Results

SVGS identifies Mre11 mutations as sae2Δ suppressors

To gain insights into why yeast cells lacking Sae2 are hypersensitive to DNA-damaging agents, we performed synthetic viability genomic screening (SVGS; Fig1A). To do this, we took cultures of a sae2Δ yeast strain (bearing a full deletion of the SAE2 locus) and plated them on YPD plates supplemented with camptothecin, which stabilises DNA topoisomerase I cleavage complexes and yields replication-dependent DSBs that are repaired by Sae2-dependent HR (Deng et al, 2005) (Fig1A). Thus, we isolated 48 mutants surviving camptothecin treatment that spontaneously arose in the population analysed. In addition to verifying that all indeed contained the SAE2 gene deletion yet were camptothecin resistant, subsequent analyses revealed that 10 clones were also largely or fully suppressed for sae2Δ hypersensitivity to the DNA-alkylating agent methyl methanesulphonate (MMS), the replication inhibitor hydroxyurea (HU), the DSB-generating agent phleomycin and ultraviolet light (Supplementary Fig S1).

Figure 1.

- Outline of the screening approach that was used to identify suppressors of sae2Δ camptothecin (CPT) hypersensitivity.

- Validation of the suppression phenotypes; a subset (sup25–sup30) of the suppressors recovered from the screening is shown along with mutations identified in each clone.

- Summary of the results of the synthetic viability genomic screening (SVGS) for sae2Δ camptothecin (CPT) hypersensitivity. The ORF and the type of mutation are reported together with the number of times each ORF was found mutated and the number of clones in which each ORF was putatively driving the resistance.

To identify mutations causing these suppression phenotypes, genomic DNA from the 48 clones was isolated and analysed by next-generation Illumina sequencing. We then used bioinformatics tools (see Materials and Methods) to identify mutations altering open reading frames within the reference S. cerevisiae genome (Fig1A). This revealed that 24 clones displaying camptothecin resistance but retaining sae2Δ hypersensitivity towards other DNA-damaging agents possessed TOP1 mutations (Fig1B and C), thereby providing proof-of-principle for the SVGS methodology (TOP1 is a non-essential gene that encodes DNA topoisomerase I, the camptothecin target). Strikingly, of the remaining clones, 10 contained one or other of two different mutations in a single MRE11 codon, resulting in amino acid residue His37 being replaced by either Arg or Tyr (mre11-H37R and mre11-H37Y, respectively; Fig1B and C and Supplementary Fig S1; note that TOP1 and MRE11 mutations are mutually exclusive). While some remaining clones contained additional potential suppressor mutations worthy of further examination, these were only resistant to camptothecin. Because of their broader phenotypes and undefined mechanism of action, we focused on characterising the MRE11 sae2Δ suppressor (mre11SUPsae2Δ) alleles.

mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles suppress many sae2Δ phenotypes

Mre11 His37 lies within a functionally undefined but structurally evolutionarily conserved α-helical region, and the residue is well conserved among quite divergent fungal species (Fig2A). As anticipated from previous studies, deleting MRE11 did not suppress the DNA damage hypersensitivities of sae2Δ cells, revealing that mre11-H37R and mre11-H37Y were not behaving as null mutations (unpublished observation). In line with this, the mre11-H37R and mre11-H37Y alleles did not destabilise Mre11, producing proteins that were expressed at equivalent levels to the wild-type protein (Fig2B). Nevertheless, expression of wild-type Mre11 resensitised the mre11SUPsae2Δ sae2Δ strains to camptothecin, and to a lesser extent to MMS (Fig2C), indicating that mre11-H37R and mre11-H37Y were fully or partially recessive for the camptothecin and MMS resistance phenotypes, respectively. Furthermore, this established that expression of wild-type Mre11 is toxic to sae2Δmre11SUPsae2Δ cells upon camptothecin treatment. Importantly, independent introduction of mre11-H37R and mre11-H37Y alleles in a sae2Δ strain confirmed that each conferred suppression of sae2Δ hypersensitivity to various DNA-damaging agents (Fig2D). The mre11-H37R and mre11-H37Y alleles also suppressed camptothecin hypersensitivity caused by mutations in Sae2 that prevent its Mec1/Tel1-dependent (sae2-MT) or CDK-dependent (sae2-S267A) phosphorylation (Baroni et al, 2004; Huertas et al, 2008) (Fig2E and F). By contrast, no suppression of sae2Δ camptothecin hypersensitivity was observed by mutating His37 to Ala (mre11-H37A; Fig2G), suggesting that the effects of the mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles were not mediated by the abrogation of a specific function of His37 but more likely reflected functional alteration through introducing bulky amino acid side chains.

Figure 2.

- A Alignment of Mre11 region containing H37 in fungal species; secondary structure prediction is shown above.

- B Western blot with anti-Mre11 antibody on protein extracts prepared from the indicated strains shows that mre11-H37R and mre11-H37Y mutations do not alter Mre11 protein levels (* indicate cross-reacting proteins).

- C sup28 and sup29 suppression is rescued by expressing wild-type (wt) Mre11.

- D mre11-H37R and mre11-H37Y suppress sae2Δ DNA damage hypersensitivity.

- E, F mre11-H37Y suppresses DNA damage hypersensitivities of sae2MT (sae2-2,5,6,8,9) and sae2-S267A cells. CPT, camptothecin; Phleo, phleomycin.

- G mre11-H37A does not suppress sae2Δ.

mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles do not suppress all sae2Δ phenotypes

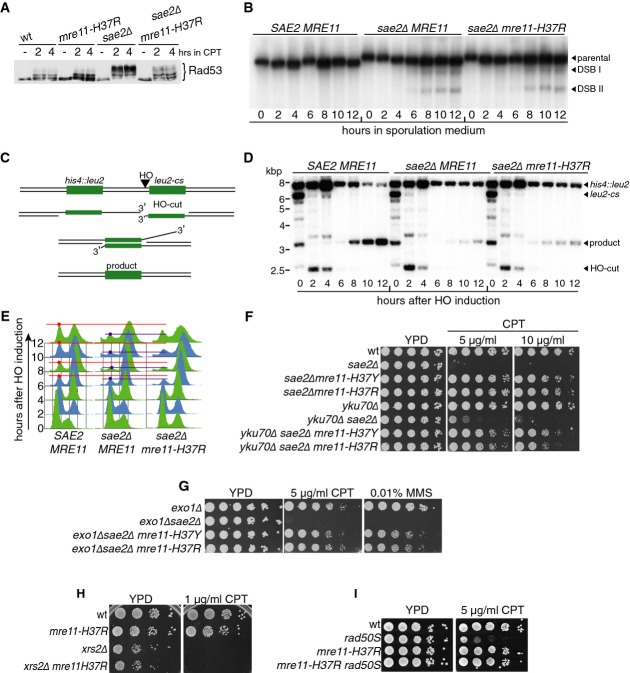

In the absence of Sae2, cells display heightened DNA damage signalling as measured by Rad53 hyperphosphorylation (Clerici et al, 2006). As we had found for the DNA damage hypersensitivities of sae2Δ cells, this read-out of Sae2 inactivity was also rescued by mre11-H37R (Fig3A). By contrast, mre11-H37R did not suppress the sporulation defect of sae2Δ cells (unpublished observation). In line with this, mre11-H37R did not suppress impaired meiotic DSB processing caused by Sae2 deficiency, as reflected by aberrant accumulation of 5′-bound Spo11 repair intermediates within the THR4 recombination hot spot (Goldway et al, 1993; Fig3B; as shown in Supplementary Fig S2A, mre11-H37R did not itself cause meiotic defects when Sae2 was present). Notably, however, mre11-H37R rescued the hypersensitivity of sae2Δ cells to etoposide, which produces DSBs bearing 5′ DNA ends bound to Top2 (Supplementary Fig S2B; deletion of ERG6 was used to increase permeability of the plasma membrane to etoposide), suggesting that significant differences must exist between the repair of meiotic and etoposide-induced DSBs.

Figure 3.

- A mre11-H37R suppresses sae2Δ checkpoint hyperactivation.

- B mre11-H37R does not rescue sae2Δ meiotic DSB processing defect.

- C Outline of DSB repair by single-strand annealing (SSA).

- D mre11-H37R does not rescue the SSA repair defect of sae2Δ strains.

- E mre11-H37R does not rescue sae2Δ-dependent cell cycle arrest caused by DSB induction.

- F, G Exo1 and Ku are not required for mre11-H37R-mediated suppression of sae2Δ hypersensitivity.

- H mre11-H37R does not suppress xrs2Δ camptothecin (CPT) hypersensitivity.

- I mre11-H37R suppresses rad50S CPT hypersensitivity.

Next, we examined the effects of mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles on Sae2-dependent DSB repair by single-strand annealing (SSA), using a system wherein a chromosomal locus contains an HO endonuclease cleavage site flanked by two direct sequence repeats. In this system, HO induction produces a DSB that is then resected until two complementary sequences become exposed and anneal, resulting in repair by a process that deletes the region between the repeats (Fishman-Lobell et al, 1992; Vaze et al, 2002; Fig3C). Despite displaying only mild resection defects (Clerici et al, 2006), we observed that sae2Δ cells were defective in SSA-mediated DSB repair and did not resume cell cycle progression after HO induction as fast as wild-type cells, in agreement with published work (Clerici et al, 2005). Notably, mre11-H37R did not alleviate these sae2Δ phenotypes (Fig3D and E).

Finally, we examined the effect of the mre11-H37R mutation on telomere-associated functions of the MRX complex and Sae2. It has been established that simultaneous deletion of SGS1 and SAE2 results in synthetic lethality/sickness, possibly due to excessive telomere shortening (Mimitou & Symington, 2008; Hardy et al, 2014). To test whether mre11-H37R can alleviate this phenotype, we crossed a sae2Δmre11-H37R strain with a sgs1Δ strain. As shown in Supplementary Fig S2C, we were unable to recover neither sgs1Δsae2Δ nor sgs1Δsae2Δmre11-H37R cells, implying that mre11-H37R cannot suppress this phenotype. In agreement with this conclusion, the mre11-H37R mutation did not negatively affect Mre11-dependent telomere maintenance as demonstrated by Southern blot analysis (Supplementary Fig S2D).

Together, the above data revealed that mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles suppressed sae2Δ DNA damage hypersensitivities but not sae2Δ meiotic phenotypes requiring Mre11-mediated Spo11 removal from recombination intermediates, nor mitotic SSA functions that have been attributed to Sae2-mediated DNA-end bridging (Clerici et al, 2005). Subsequent analyses revealed that suppression did not arise largely through channelling of DSBs towards NHEJ because the key NHEJ factor Yku70 was not required for mre11-H37R or mre11-H37Y to suppress the camptothecin sensitivity of a sae2Δ strain (Fig3F). In addition, this analysis revealed that the previously reported suppression of sae2Δ-mediated DNA damage hypersensitivity by Ku loss (Mimitou & Symington, 2010; Foster et al, 2011) was considerably less effective than that caused by mre11-H37R or mre11-H37Y. Also, suppression of sae2Δ camptothecin hypersensitivity by mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles did not require Exo1, indicating that in contrast to suppression of sae2Δ phenotypes by Ku loss (Mimitou & Symington, 2010), mre11-H37R and mre11-H37Y did not cause cells to become particularly reliant on Exo1 for DSB processing (Fig3G). Further characterisations, focused on mre11-H37R, revealed that while not suppressing camptothecin hypersensitivity of an xrs2Δ strain (Fig3H), it almost fully rescued the camptothecin hypersensitivity of a strain expressing the rad50S allele, which phenocopies sae2Δ by somehow preventing functional Sae2–MRX interactions that are required for Sae2 stimulation of Mre11 endonuclease activity (Keeney & Kleckner, 1995; Hopfner et al, 2000; Cannavo & Cejka, 2014; Fig3I).

H37R does not enhance Mre11 nuclease activity but impairs DNA binding

To explore how mre11SUPsae2Δ mutations might operate, we over-expressed and purified wild-type Mre11, Mre11H37R and Mre11H37A (Fig4A and Supplementary Fig S2F) and then subjected these to biochemical analyses. All the proteins were expressed at similar levels and fractionated with equivalent profiles, suggesting that the Mre11 mutations did not grossly affect protein structure or stability. Since Sae2 promotes Mre11 nuclease functions, we initially speculated that sae2Δ suppression would be mediated by mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles having intrinsically high, Sae2-independent nuclease activity. Surprisingly, this was not the case, with Mre11H37R actually exhibiting lower nuclease activity than the wild-type protein (Fig4B). Furthermore, by electrophoretic mobility shift assays, we found that the H37R mutation reduced Mre11 binding to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA; Fig4C) and abrogated Mre11 binding to ssDNA (Fig4D). Conversely, mutation of H37 to alanine, which does not result in a supsae2Δ phenotype, did not negatively affect dsDNA-binding activity (Fig4C) and only partially impaired ssDNA binding (Fig4D).

Figure 4.

- A Mre11 and Mre11H37R were purified to homogeneity from yeast cultures.

- B 3′ exonuclease activity assay on Mre11 and Mre11H37R leading to release of a labelled single nucleotide, as indicated.

- C, D Electrophoretic mobility shift assays on Mre11, Mre11H37R and Mre11H37A with dsDNA (C) or ssDNA (D).

- E Quantification of mre11-H37R suppression of sae2Δ cell DNA damage hypersensitivity. Overnight grown cultures of the indicated strains were diluted and plated on medium containing the indicated doses of CPT. Colony growth was scored 3–6 days later. Averages and standard deviations are shown for each point.

- F Intragenic suppression of CPT hypersensitivity of mre11-nd (mre11-H125N) by mre11-H37R. Overnight grown cultures of the indicated strains were treated as in (E). Dotted lines represent data from (E). Averages and standard deviations are shown for each point.

- G Mre11 nuclease activity is not required for mre11-H37R-mediated suppression of sae2Δ CPT hypersensitivity. Overnight grown cultures of the indicated strains were treated as in (E). The dotted lines represent data from (E). Averages and standard deviations are shown for each point.

Taken together with the fact that the lack of Sae2 only has minor effects on mitotic DSB resection (Clerici et al, 2005), the above results suggested that the sae2Δ suppressive effects of mre11SUPsae2Δ mutations were associated with weakened Mre11 DNA binding and were not linked to effects on resection or Mre11 nuclease activity. In line with this idea, by combining mutations in the same Mre11 polypeptide, we established that mre11-H37R substantially rescued camptothecin hypersensitivity caused by mutating the Mre11 active site residue His125 to Asn (Moreau et al, 2001; mre11-H125N; Fig4E and Supplementary Fig S2F and G), which abrogates all Mre11 nuclease activities and prevents processing of DSBs when their 5′ ends are blocked (Moreau et al, 1999). Even sae2Δ mre11-H37R,H125N cells were resistant to camptothecin and MMS, indicating that Mre11-nuclease-mediated processing of DNA ends is not required for H37R-dependent suppression, nor for DNA repair in this Sae2-deficient setting (Fig4G and Supplementary Fig S2G). Furthermore, while sae2Δ strains were more sensitive to camptothecin than mre11-H125N strains, the sensitivities of the corresponding strains carrying the mre11-H37R allele were comparable (compare curves 1 and 2 with 3 and 4 in Fig4F) indicating that mre11-H37R suppresses not only the sae2Δ-induced lack of Mre11 nuclease activity, but also other nuclease-independent functions of Sae2. Nevertheless, mre11-H37R did not rescue the camptothecin hypersensitivity of sae2Δ cells to wild-type levels, suggesting that not all functions of Sae2 are suppressed by this MRE11 allele (Fig4E and F).

Identifying an Mre11 interface mediating sae2Δ suppression

To gain further insights into how mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles operate and relate this to the above functional and biochemical data, we screened for additional MRE11 mutations that could suppress camptothecin hypersensitivity caused by Sae2 loss. Thus, we propagated a plasmid carrying wild-type MRE11 in a mutagenic E. coli strain, thereby generating libraries of plasmids carrying mre11 mutations. We then introduced these libraries into a sae2Δmre11Δ strain and screened for transformants capable of growth in the presence of camptothecin (Fig5A). Through plasmid retrieval, sequencing and functional verification, we identified 12 sae2Δ suppressors, nine carrying single mre11 point mutations and three being double mutants (Supplementary Fig S3A). One single mutant was mre11-H37R, equivalent to an initial spontaneously arising suppressor that we had identified. Among the other single mutations were mre11-P110L and mre11-L89V, both of which are located between Mre11 nuclease domains II and III, in a region with no strong secondary structure predictions (Fig5B). Two of the three double mutants contained mre11-P110L combined with another mutation that was presumably not responsible for the resistance phenotype (because mre11-P110L acts as a suppressor on its own), whereas the third contained both mre11-Q70R and mre11-G193S. Subsequent studies, involving site-directed mutagenesis, demonstrated that effective sae2Δ suppression was mediated by mre11-Q70R, which alters a residue located in a highly conserved α-helical region (Fig5C). Ensuing comparisons revealed that the mutations identified did not alter Mre11 protein levels (Supplementary Fig S3B) and that mre11-Q70R suppressed sae2Δ camptothecin hypersensitivity to similar extents as mre11-H37R and mre11-H37Y, whereas mre11-L89V and mre11-P110L were marginally weaker suppressors (Fig5D).

Figure 5.

- Outline of the plasmid mutagenesis approach to identify new mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles. LOF: loss-of-function alleles. SUP: suppressor alleles.

- Mre11 with shaded boxes and blue shapes indicating phosphoesterase motifs and secondary structures, respectively; additional mre11SUPsae2Δ mutations recovered from the screening are indicated.

- Fungal alignment and secondary structure prediction of the region of Mre11 containing Q70.

- mre11-Q70R, mre11-L89V and mre11-P110L alleles recovered from plasmid mutagenesis screening suppress sae2Δ hypersensitivity to camptothecin.

- Structural prediction of S. cerevisiae Mre11 residues 1–414, obtained by homology modelling using the corresponding S. pombe and human structures. The water-accessible surface of the two monomers is shown in different shades of blue. Red: residues whose mutation suppresses sae2Δ DNA damage hypersensitivity. Orange: residues whose mutation abrogates Mre11 nuclease activity.

- Model of Mre11 tertiary structure (residues 1–100). Residues are colour-coded as in (E).

- Top: mre11-L77R suppresses the DNA damage hypersensitivity of sae2Δ cells. Bottom: localisation of mre11SUPsae2Δ suppressors on the molecular model of the Mre11 dimer. The two Mre11 monomers are shown in different shades of blue, and the proposed path of bound ssDNA is indicated by the orange filament.

- Model in which the two DNA filaments of the two DSB ends melt when binding to Mre11; the 5′ ends being channelled towards the active site and the 3′ end being channelled towards the Mre11SUPsae2Δ region.

To map the locations of the various mre11SUPsae2Δ mutations within the Mre11 structure, we used the dimeric tertiary structure (Schiller et al, 2012) of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe Mre11 counterpart, Rad32, as a template to generate a molecular model of S. cerevisiae Mre11. The resulting structure had a near-native QMEAN score (0.705 vs 0.778; Benkert et al, 2008), indicating a reliable molecular model. Strikingly, ensuing analyses indicated that the mre11SUPsae2Δ mutations clustered in a region of the protein structure distal from the nuclease catalytic site and adjacent to, but distinct from, the interface defined as mediating contacts with dsDNA in the Pyrococcus furiosus Mre11 crystal structure (Williams et al, 2008; Fig5E; the predicted path of dsDNA is shown in black, while the mre11SUPsae2Δ mutations and residues involved in nuclease catalysis are indicated in red and orange, respectively). Furthermore, this analysis indicated that H37 and Q70 are located close together, on two parallel α-helices and are both likely to be solvent exposed (Fig5F). By contrast, the L89 side chain is predicted to be in the Mre11 hydrophobic core, although modelling suggested that the mre11-L89V mutation might alter the stability of the α-helix containing Q70. We noted that, in the context of the Mre11 dimer, H37 and Q70 are located in a hemi-cylindrical concave area directly below the position where dsDNA is likely to bind (Fig5E right, shown by pink hemispheres). Furthermore, by specifically mutating other nearby residues to arginine, we found that the mre11-L77R mutation also strongly suppressed sae2Δ camptothecin hypersensitivity (Fig5G). As discussed further below, while it is possible that certain mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles somehow influence the established dsDNA-binding interface of Mre11, we speculate that mre11-H37R/Y and mre11-Q70R, and at least some of the other suppressors, act by perturbing interactions normally mediated between the Mre11 hemi-cylindrical concave region and ssDNA (modelled in Fig5G and discussed further below). Consistent with this idea, we found that the Mre11Q70R protein was markedly impaired in binding to ssDNA but not to dsDNA (Supplementary Figs S2E and S3C). However, because P110 lies in the ‘latching loop’ region of eukaryotic Mre11 that is likely to mediate contacts with Xrs2 (Schiller et al, 2012), sae2Δ suppression by this mutation might arise through altering such contacts. A recent report by L. Symington and colleagues reached similar conclusions (Chen et al, 2015).

Taken together, our findings suggested that, in addition to its established dsDNA-binding mode, Mre11 mediates distinct, additional functional contacts with DNA that, when disrupted, lead to suppression of sae2Δ phenotypes. Thus, we suggest that, during DSB processing, duplex DNA entering the Mre11 structure may become partially unwound, with the 5′ end being channelled towards the nuclease catalytic site and the resulting ssDNA—bearing the 3′ terminal OH—interacting with an adjacent Mre11 region that contains residues mutated in mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles (Fig5G and H). In this regard, we note that Mre11 was recently shown in biochemical studies to promote local DNA unwinding (Cannon et al, 2013). Such a model would explain our biochemical findings, and would also explain our biological data if persistent Mre11 binding to the nascent 3′ terminal DNA impairs HR unless counteracted by the actions of Sae2 or weakened by mre11SUPsae2Δ alleles.

sae2Δ phenotypes reflect Mre11-bound DNA repair intermediates

A prediction arising from the above model is that Mre11 persistence and associated Tel1 hyperactivation in sae2Δ cells would be counteracted by mre11SUPsae2Δ mutations. To test this, we constructed yeast strains expressing wild-type Mre11 or Mre11H37R fused to yellow-fluorescent protein (YFP) and then used fluorescence microscopy to examine their recruitment and retention at sites of DNA damage induced by ionising radiation. In line with published work (Lisby et al, 2004), recruitment of wild-type Mre11 to DNA damage foci was more robust and persisted longer when Sae2 was absent (Fig6A). Moreover, such Mre11 DNA damage persistence in sae2Δ cells was largely attenuated by mre11-H37R (Fig6A; compare red and orange curves). By contrast, mre11-H37R had little or no effect on Mre11 recruitment and dissociation kinetics when Sae2 was present (compare dark and light blue curves). Importantly, we found that HR-mediated DSB repair was not required for H37R-induced suppression of Mre11-focus persistence in sae2Δ cells, as persistence and suppression still occurred in the absence of the key HR factor, Rad51 (Fig6B). Also, in accord with our other observations, we found that the rad50S allele caused Mre11 DNA damage-focus persistence in a manner that was suppressed by the mre11-H37R mutation (Fig6C).

Figure 6.

- IR-induced Mre11H37R foci (IRIF) persist for shorter times than Mre11-wt IRIF in exponentially growing sae2Δ cells (average and standard deviations from two or more independent experiments).

- Effects of sae2Δ and mre11-H37R on Mre11 IRIF persistence still occur when Rad51 is absent, revealing that Mre11 IRIF persistence causes defective HR (average and standard deviation from two independent experiments).

- mre11-H37R suppresses Mre11 IRIF persistence in exponentially growing rad50S cells (average and standard deviation from two independent experiments).

Previous work has established that Mre11 persistence on DSB ends, induced by lack of Sae2, leads to enhanced and prolonged DNA damage-induced Tel1 activation, associated with Rad53 hyperphosphorylation (Usui et al, 2001; Lisby et al, 2004; Clerici et al, 2006; Fukunaga et al, 2011). Supporting our data indicating that, unlike wild-type Mre11, Mre11H37R is functionally released from DNA ends even in the absence of Sae2, we found that in a mec1Δ background (in which Tel1 is the only kinase activating Rad53; Sanchez et al, 1996), DNA damage-induced Rad53 hyperphosphorylation was suppressed by mre11-H37R (Fig7A).

Figure 7.

- mre11-H37R suppresses Tel1 hyperactivation induced by Mre11 IRIF persistence in sae2Δ cells.

- Deletion of TEL1 weakens the suppression of the sensitivity of a sae2Δ strain mediated by mre11-H37R.

- Deletion of TEL1 reduces the hyperaccumulation of Mre11 to IRIF and impairs the suppression of their persistence mediated by mre11-H37R (average and standard deviation from two independent experiments).

- mre11-H37R suppresses the sensitivity to CPT of a tel1Δ strain.

- Model for the role of MRX, Sae2 and Tel1 in response to DSBs.

While we initially considered the possibility that persistent Tel1 hyperactivation might cause the DNA damage hypersensitivity of sae2Δ cells, we concluded that this was unlikely to be the case because TEL1 inactivation did not suppress sae2Δ DNA damage hypersensitivity phenotypes (Supplementary Fig S3D). Furthermore, Tel1 loss actually reduced the ability of mre11-H37R to suppress the camptothecin hypersensitivity of sae2Δ cells (Fig7B). In accord with this, in the absence of Tel1, mre11-H37R no longer affected the dissociation kinetics of IR-induced Mre11 foci in sae2Δ cells (Fig7C). Collectively, these data suggested that Tel1 functionally cooperates with Sae2 to promote the removal of Mre11 from DNA ends. In this regard, we noted that mre11-H37R suppressed the moderate camptothecin hypersensitivity of a tel1Δ strain (Fig7D). We therefore propose that, while persistent DNA damage-induced Tel1 activation is certainly a key feature of sae2Δ cells, it is persistent binding of the MRX complex to nascent 3′ terminal DNA that causes toxicity in sae2Δ cells, likely through it delaying downstream HR events. Accordingly, mutations that reduce Mre11 ssDNA binding enhance the release of the Mre11 complex from DSB ends in the absence of Sae2, through events promoted by Tel1 (Fig7E). In this model, Mre11 persistence at DNA damage sites is a cause, and not just a consequence, of impaired HR-mediated repair in sae2Δ cells.

Discussion

Our data help resolve apparent paradoxes regarding Sae2 and MRX function by suggesting a revised model for how these and associated factors function in HR (Fig7E). In this model, after being recruited to DSB sites and promoting Tel1 activation, resection and ensuing Mec1 activation, the MRX complex disengages from processed DNA termini in a manner promoted by Sae2 and facilitated by Tel1 and Mre11 nuclease activity. Sae2 is required to stimulate Mre11 nuclease activity (Cannavo & Cejka, 2014) and subsequently to promote MRX eviction from the DSB end. However, our data suggest that Sae2 can also promote MRX eviction in the absence of DNA-end processing, as mre11-H37R suppresses the phenotypes caused by sae2Δ and mre11-nd to essentially the same extent. Thus, according to our model, when Sae2 is absent, both the nuclease activities of Mre11 and MRX eviction are impaired. Under these circumstances, despite resection taking place—albeit with somewhat slower kinetics than in wild-type cells—MRX persists on ssDNA bearing the 3′ terminal OH, thereby delaying repair by HR. In cells containing the mre11-H37R mutation, however, weakened DNA binding together with Tel1 activity promotes MRX dissociation from DNA even in the absence of Sae2, thus allowing the nascent ssDNA terminus to effectively engage in the key HR events of strand invasion and DNA synthesis (Fig7E). Nevertheless, it is conceivable that abrogation of pathological Tel1-mediated checkpoint hyperactivation contributes to the resistance of sae2Δmre11-H37R cells to DNA-damaging agents. In this regard, we note that the site of one of the sae2Δ suppressors, P110, lies in the ‘latching loop’ region of eukaryotic Mre11 that is likely to mediate contacts with Xrs2 (Schiller et al, 2012), suggesting that, in this case, sae2Δ suppression might arise through weakening this interaction and dampening Tel1 activity.

Our results also highlight how the camptothecin hypersensitivity of strains carrying a nuclease-defective version of Mre11 does not reflect defective Mre11-dependent DNA-end processing per se, but rather stems from stalling of MRX on DNA ends. We propose that this event delays or prevents HR, possibly by impairing the removal of 3′-bound Top1 as is suggested by the fact that in S. pombe, rad50S or mre11-nd alleles are partially defective in Top1 removal from damaged DNA (Hartsuiker et al, 2009). This interpretation also offers an explanation for the higher DNA damage hypersensitivity of sae2Δ cells compared to cells carrying mre11-H125N alleles: while sae2Δ cells are impaired in both Mre11 nuclease activity and Mre11 eviction—leading to MRX persistence at DNA damage sites and Tel1 hyperactivation—mre11-H125N cells are only impaired in Mre11 nuclease activity. Indeed, despite having no nuclease activity, the mre11-H125N mutation does not impair NHEJ, telomere maintenance, mating type switching or Mre11 interaction with Rad50/Xrs2 or interfere with the recruitment of the Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 complex to foci at sites of DNA damage (Moreau et al, 1999; Lisby et al, 2004; Krogh et al, 2005). In addition, our model explains why the mre11-H37R mutation does not suppress meiotic defects of sae2Δ cells, because Sae2-stimulated Mre11 nuclease activity is crucial for removing Spo11 from meiotic DBS 5′ termini. Finally, this model explains why mre11-H37R does not suppress the sae2Δ deficiency in DSB repair by SSA because the sae2Δ defect in SSA is suggested to stem from impaired bridging between the two ends of a DSB rather than from the persistence of MRX on DNA ends (Clerici et al, 2005; Andres et al, 2015; Davies et al, 2015). In this regard, we note that SSA does not require an extendable 3′-OH DNA terminus to proceed and so could ensue even in the presence of blocked 3′-OH DNA ends.

We have also found that the mre11-H37R mutation suppresses the DNA damage hypersensitivities of cells impaired in CDK- or Mec1/Tel1-mediated Sae2 phosphorylation. This suggests that such kinase-dependent control mechanisms—which may have evolved to ensure that HR only occurs after the DNA damage checkpoint has been triggered—also operate, at least in part, at the level of promoting MRX removal from partly processed DSBs. Accordingly, we found that TEL1 deletion causes moderate hypersensitivity to camptothecin that can be rescued by the mre11-H37R allele, implying that the same type of toxic repair intermediate is formed in sae2Δ and tel1Δ cells and that in each case, this can be rescued by MRX dissociation caused by mre11-H37R (Fig7E). Supporting this idea, it has been previously shown that resection relies mainly on Exo1 in both tel1Δ and sae2Δ cells (Clerici et al, 2006; Mantiero et al, 2007). We suggest that the comparatively mild hypersensitivity of tel1Δ strains to camptothecin is due to Tel1 loss allowing DSB repair intermediates to be channelled into a different pathw ay, in which Exo1-dependent resection (Mantiero et al, 2007) leads to the activation of Mec1, which can then promote Sae2 phosphorylation and subsequent MRX removal (Fig7E). The precise role of Tel1 in these events is not yet clear, although during the course of our analyses, we found that the deletion of TEL1 reduced the suppressive effects of mre11-H37R on sae2Δ DNA damage sensitivity and Mre11-focus persistence. This suggests that, in the absence of Sae2, Tel1 facilitates MRX eviction by mre11-H37R, possibly by phosphorylating the MRX complex itself.

Given the apparent strong evolutionary conservation of Sae2, the Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 complex and their associated control mechanisms, it seems likely that the model we have proposed will also apply to other systems, including human cells. Indeed, we speculate the profound impacts of proteins such as mammalian CtIP and BRCA1 on HR may not only relate to their effects on resection but may also reflect them promoting access to ssDNA bearing 3′ termini so that HR can take place effectively. Finally, our data highlight the power of SVGS to identify genetic interactions—including those such that we have defined that rely on separation-of-function mutations rather than null ones—and also to inform on underlying biological and biochemical mechanisms. In addition to being of academic interest, such mechanisms are likely to operate in medical contexts, such as the evolution of therapy resistance in cancer.

Materials and Methods

Strain and plasmid construction

Yeast strains used in this work are derivatives of SK1 (meiotic phenotypes), YMV80 (SSA phenotypes) and haploid derivatives of W303 (all other phenotypes). All deletions were introduced by one-step gene disruption. pRS303-derived plasmids, carrying a wt or mutant MRE11 version, were integrated at the MRE11 locus in an mre11Δ::KanMX6 strain. Alternatively, the same strain was transformed with pRS416-derived plasmids containing wild-type or mutant MRE11 under the control of its natural promoter. Strains expressing mutated mre11-YFP were obtained in two steps: integration of a pRS306-based plasmid (pFP118.1) carrying a mutated version of Mre11 in a MRE11-YPF sae2Δ strain, followed by selection of those ‘pop-out’ events that suppressed camptothecin hypersensitivity of the starting strain. The presence of mutations was confirmed by sequencing. Full genotypes of the strains used in this study are described in Supplementary Table S1; plasmids are described in Supplementary Table S2.

Whole-genome paired-end DNA sequencing and data analysis

DNA (1–3 μg) was sheared to 100–1,000 bp by using a Covaris E210 or LE220 (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA) and size-selected (350–450 bp) with magnetic beads (Ampure XP; Beckman Coulter). Sheared DNA was subjected to Illumina paired-end DNA library preparation and PCR-amplified for six cycles. Amplified libraries were sequenced with the HiSeq platform (Illumina) as paired-end 100 base reads according to the manufacturer's protocol. A single sequencing library was created for each sample, and the sequencing coverage per sample is given in Supplementary Table S3. Sequencing reads from each lane were aligned to the S. cerevisiae S288c assembly (R64-1-1) from Saccharomyces Genome Database (obtained from the Ensembl genome browser) by using BWA (v0.5.9-r16) with the parameter ‘-q 15’. All lanes from the same library were then merged into a single BAM file with Picard tools, and PCR duplicates were marked by using Picard ‘MarkDuplicates’ (Li et al, 2009). All of the raw sequencing data are available from the ENA under accession ERP001366. SNPs and indels were identified by using the SAMtools (v0.1.19) mpileup function, which finds putative variants and indels from alignments and assigns likelihoods, and BCFtools that performs the variant calling (Li et al, 2009). The following parameters were used: for SAMtools (v0.1.19) mpileup -EDS -C50 -m2 -F0.0005 -d 10,000’ and for BCFtools (v0.1.19) view ‘-p 0.99 -vcgN’. Functional consequences of the variants were produced by using the Ensembl VEP (McLaren et al, 2010).

MRE11 random mutagenesis

Plasmid pRS316 carrying MRE11 coding sequence under the control of its natural promoter was transformed into mutagenic XL1-Red competent E. coli cells (Agilent Technologies) and propagated following the manufacturer's instructions. A plasmid library of ∽3,000 independent random mutant clones was transformed into mre11Δsae2Δ cells, and transformants were screened for their ability to survive in the presence of camptothecin. Plasmids extracted from survivors loosing their camptothecin resistance after a passage on 5-fluoro-orotic acid (FOA) were sequenced and independently reintroduced in a mre11Δsae2Δ strain.

Molecular modelling

A monomeric molecular model of S. cerevisiae Mre11 was generated with the homology modelling program MODELLER (Sali & Blundell, 1993) v9.11, using multiple structures of Mre11 from S. pombe (PDB codes: 4FBW and 4FBK) and human (PDB code: 3T1I) as templates. A structural alignment of them was made with the program BATON (Sali & Blundell, 1990) and manually edited to remove unmatched regions. The quality of the model was found to be native-like as evaluated by MODELLER's NDOPE (−1.2) and GA341 (1.0) metrics and the QMEAN server (Benkert et al, 2009) (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/qmean/) (0.705). The monomeric model was subsequently aligned on the dimeric assembly of the 4FBW template to generate a dimer, and the approximate position of DNA binding was determined by aligning the P. furiosus structure containing dsDNA (PDB code: 3DSC) with the dimeric model. All images were obtained using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System.

Microscopy

Exponentially growing yeast strains carrying wild-type or mutant Mre11-YFP were treated with 40 Gy of ionising radiations with a Faxitron irradiator (CellRad). At regular intervals, samples were taken and fixed with 500 μl of Fixing Solution (4% paraformaldehyde, 3.4% sucrose). Cells were subsequently washed with wash solution (100 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.5, 1.2 M sorbitol) and mounted on glass slides. Images were taken at a DeltaVision microscope. All these experiments were carried out at 30°C.

In vitro assays

For the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), a radiolabelled DNA substrate (5 nM) was incubated with the indicated amount of Mre11 or Mre11H37R in 10 μl buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 100 μg/ml BSA, 150 mM KCl) at 30°C for 10 min. The reaction mixtures were resolved in a 10% polyacrylamide gel in TBE buffer (89 mM Tris–borate, pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA). The gel was dried onto Whatman DE81 paper and then subjected to phosphorimaging analysis. For nuclease assay, 1 mM MnCl2 was added to the reactions and the reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 20 min and deproteinised by treatment with 0.5% SDS and 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K for 5 min at 37°C before analysis in a 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in TBE buffer.

Additional Materials and Methods can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank M.P. Longhese, R. Rothstein and J. Haber for providing strains and plasmids; Sir T. Blundell and T. Ochi for advice on structural biology and for providing comments to the manuscript. Research in the Jackson laboratory is funded by Cancer Research UK Programme Grant C6/A11224, the European Research Council and the European Community Seventh Framework Programme Grant Agreement No. HEALTH-F2-2010-259893 (DDResponse). Core funding is provided by CRUK (C6946/A14492) and the Wellcome Trust (WT092096). SPJ receives his salary from the University of Cambridge, UK, supplemented by CRUK. TO, IG and FP were funded by Framework Programme Grant Agreement No. HEALTH-F2-2010-259893 (DDResponse). FP also received funding from EMBO (Fellowship ALTF 1287-2011); NG and IS are funded by the Wellcome Trust (101126/Z/13/Z). DJA and TMK were supported by Cancer Research UK and the Wellcome Trust (WT098051). PS and HN were supported by NIH grants RO1ES007061 and K99ES021441, respectively.

Author contributions

The initial screening was conceived and designed by TO, EV, DJA and SPJ. Alignment of whole-genome sequencing data, variant calling and subsequent analysis was carried out by MH and TMK. Experiments for the in vivo characterisation of the mre11-H37R mutant were conceived by TO, IG, FP and SPJ, and were carried out by TO, FP, IG, NJG, EV and IS. Biochemical assays were designed by SPJ, PS and HN and carried out by HN. The identification of further mre11supsae2Δ mutants was designed by FP and SPJ and carried out by NJG. Modelling of S. cerevisiae Mre11 was performed by BO-M, and subsequent analyses were carried out by BO-M and FP. The manuscript was largely written by SPJ and FP, and was edited by all other authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

Supplementary Table S1

Supplementary Table S2

Supplementary Table S3

Supplementary Methods

Supplementary Legends

Review Process File

References

- Andres SN, Appel CD, Westmoreland JW, Williams JS, Nguyen Y, Robertson PD, Resnick MA, Williams RS. Tetrameric Ctp1 coordinates DNA binding and DNA bridging in DNA double-strand-break repair. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:158–166. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baroni E, Viscardi V, Cartagena-Lirola H, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. The functions of budding yeast Sae2 in the DNA damage response require Mec1- and Tel1-dependent phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4151–4165. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4151-4165.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton O, Naumann SC, Diemer-Biehs R, Künzel J, Steinlage M, Conrad S, Makharashvili N, Wang J, Feng L, Lopez BS, Paull TT, Chen J, Jeggo PA, Löbrich M. Polo-like kinase 3 regulates CtIP during DNA double-strand break repair in G1. J Cell Biol. 2014;206:877–894. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201401146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkert P, Tosatto SCE, Schomburg D. QMEAN: a comprehensive scoring function for model quality assessment. Proteins. 2008;71:261–277. doi: 10.1002/prot.21715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkert P, Künzli M, Schwede T. QMEAN server for protein model quality estimation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W510–W514. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannavo E, Cejka P. Sae2 promotes dsDNA endonuclease activity within Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 to resect DNA breaks. Nature. 2014;514:122–125. doi: 10.1038/nature13771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon B, Kuhnlein J, Yang S-H, Cheng A, Schindler D, Stark JM, Russell R, Paull TT. Visualization of local DNA unwinding by Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 using single-molecule FRET. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:18868–18873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309816110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Donnianni RA, Handa N, Deng SK, Oh J, Timashev LA, Kowalczykowski SC, Symington LS. Sae2 promotes DNA damage resistance by removing the Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 complex from DNA and attenuating Rad53 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E1880–E1887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503331112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici M, Mantiero D, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sae2 protein promotes resection and bridging of double strand break ends. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38631–38638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici M, Mantiero D, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sae2 protein negatively regulates DNA damage checkpoint signalling. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:212–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley JM, Palmbos PL, Wu D, Wilson TE. Nonhomologous end joining in yeast. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:431–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.113340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies OR, Forment JV, Sun M, Belotserkovskaya R, Coates J, Galanty Y, Demir M, Morton CR, Rzechorzek NJ, Jackson SP, Pellegrini L. CtIP tetramer assembly is required for DNA-end resection and repair. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:150–157. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C, Brown JA, You D, Brown JM. Multiple endonucleases function to repair covalent topoisomerase I complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2005;170:591–600. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.028795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman-Lobell J, Rudin N, Haber JE. Two alternative pathways of double-strand break repair that are kinetically separable and independently modulated. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1292–1303. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster SS, Balestrini A, Petrini JHJ. Functional interplay of the Mre11 nuclease and Ku in the response to replication-associated DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:4379–4389. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05854-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga K, Kwon Y, Sung P, Sugimoto K. Activation of protein kinase Tel1 through recognition of protein-bound DNA ends. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1959–1971. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05157-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuse M, Nagase Y, Tsubouchi H, Murakami-Murofushi K, Shibata T, Ohta K. Distinct roles of two separable in vitro activities of yeast Mre11 in mitotic and meiotic recombination. EMBO J. 1998;17:6412–6425. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldway M, Sherman A, Zenvirth D, Arbel T, Simchen G. A short chromosomal region with major roles in yeast chromosome III meiotic disjunction, recombination and double strand breaks. Genetics. 1993;133:159–169. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.2.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Churikov D, Géli V, Simon M-N. Sgs1 and Sae2 promote telomere replication by limiting accumulation of ssDNA. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5004. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartsuiker E, Neale MJ, Carr AM. Distinct requirements for the Rad32Mre11 nuclease and Ctp1CtIP in the removal of covalently bound topoisomerase I and II from DNA. Mol Cell. 2009;33:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfner KP, Karcher A, Shin DS, Craig L, Arthur LM, Carney JP, Tainer JA. Structural biology of Rad50 ATPase: ATP-driven conformational control in DNA double-strand break repair and the ABC-ATPase superfamily. Cell. 2000;101:789–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80890-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas P, Cortés-Ledesma F, Sartori AA, Aguilera A, Jackson SP. CDK targets Sae2 to control DNA-end resection and homologous recombination. Nature. 2008;455:689–692. doi: 10.1038/nature07215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas P, Jackson SP. Human CtIP mediates cell cycle control of DNA end resection and double strand break repair. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9558–9565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808906200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov EL, Sugawara N, White CI, Fabre F, Haber JE. Mutations in XRS2 and RAD50 delay but do not prevent mating-type switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3414–3425. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SP, Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461:1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney S, Kleckner N. Covalent protein-DNA complexes at the 5′ strand termini of meiosis-specific double-strand breaks in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11274–11278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney S, Giroux CN, Kleckner N. Meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breaks are catalyzed by Spo11, a member of a widely conserved protein family. Cell. 1997;88:375–384. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh BO, Llorente B, Lam A, Symington LS. Mutations in Mre11 phosphoesterase motif I that impair Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 complex stability in addition to nuclease activity. Genetics. 2005;171:1561–1570. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.049478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengsfeld BM, Rattray AJ, Bhaskara V, Ghirlando R, Paull TT. Sae2 is an endonuclease that processes hairpin DNA cooperatively with the Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 complex. Mol Cell. 2007;28:638–651. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. The sequence alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisby M, Barlow JH, Burgess RC, Rothstein R. Choreography of the DNA damage response: spatiotemporal relationships among checkpoint and repair proteins. Cell. 2004;118:699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makharashvili N, Tubbs AT, Yang S-H, Wang H, Barton O, Zhou Y, Deshpande RA, Lee J-H, Lobrich M, Sleckman BP, Wu X, Paull TT. Catalytic and noncatalytic roles of the CtIP endonuclease in double-strand break end resection. Mol Cell. 2014;54:1022–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantiero D, Clerici M, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. Dual role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Tel1 in the checkpoint response to double-strand breaks. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:380–387. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, Chen Y, Flicek P, Cunningham F. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP effect predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing. Nature. 2008;455:770–774. doi: 10.1038/nature07312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Ku prevents Exo1 and Sgs1-dependent resection of DNA ends in the absence of a functional MRX complex or Sae2. EMBO J. 2010;29:3358–3369. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau S, Ferguson JR, Symington LS. The nuclease activity of Mre11 is required for meiosis but not for mating type switching, end joining, or telomere maintenance. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:556–566. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau S, Morgan EAA, Symington LSS. Overlapping functions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mre11, exo1 and rad27 nucleases in DNA metabolism. Genetics. 2001;159:1423. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.4.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nairz K, Klein F. mre11S–-a yeast mutation that blocks double-strand-break processing and permits nonhomologous synapsis in meiosis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2272–2290. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.17.2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz S, Amon A, Klein F. Isolation of COM1, a new gene required to complete meiotic double-strand break-induced recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;146:781–795. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.3.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A, Blundell TL. Definition of general topological equivalence in protein structures. A procedure involving comparison of properties and relationships through simulated annealing and dynamic programming. J Mol Biol. 1990;212:403–428. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Y, Desany BA, Jones WJ, Liu Q, Wang B, Elledge SJ. Regulation of RAD53 by the ATM-like kinases MEC1 and TEL1 in yeast cell cycle checkpoint pathways. Science. 1996;271:357–360. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori AA, Lukas C, Coates J, Mistrik M, Fu S, Bartek J, Baer R, Lukas J, Jackson SP. Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature. 2007;450:509–514. doi: 10.1038/nature06337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller CB, Lammens K, Guerini I, Coordes B, Feldmann H, Schlauderer F, Möckel C, Schele A, Strässer K, Jackson SP, Hopfner K-P. Structure of Mre11-Nbs1 complex yields insights into ataxia-telangiectasia-like disease mutations and DNA damage signaling. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:693–700. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracker TH, Petrini JHJ. The MRE11 complex: starting from the ends. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:90–103. doi: 10.1038/nrm3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symington LS, Gautier J. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu Rev Genet. 2011;45:247–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui T, Ogawa H, Petrini JH. A DNA damage response pathway controlled by Tel1 and the Mre11 complex. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaze MB, Pellicioli A, Lee SE, Ira G, Liberi G, Arbel-Eden A, Foiani M, Haber JE. Recovery from checkpoint-mediated arrest after repair of a double-strand break requires Srs2 helicase. Mol Cell. 2002;10:373–385. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Li Y, Truong LN, Shi LZ, Hwang PY-H, He J, Do J, Cho MJ, Li H, Negrete A, Shiloach J, Berns MW, Shen B, Chen L, Wu X. CtIP maintains stability at common fragile sites and inverted repeats by end resection-independent endonuclease activity. Mol Cell. 2014;54:1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RS, Moncalian G, Williams JS, Yamada Y, Limbo O, Shin DS, Groocock LM, Cahill D, Hitomi C, Guenther G, Moiani D, Carney JP, Russell P, Tainer JA. Mre11 dimers coordinate DNA end bridging and nuclease processing in double-strand-break repair. Cell. 2008;135:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You Z, Shi LZ, Zhu Q, Wu P, Zhang Y-W, Basilio A, Tonnu N, Verma IM, Berns MW, Hunter T. CtIP links DNA double-strand break sensing to resection. Mol Cell. 2009;36:954–969. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Chung W-H, Shim EY, Lee SE, Ira G. Sgs1 helicase and two nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 resect DNA double-strand break ends. Cell. 2008;134:981–994. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

Supplementary Table S1

Supplementary Table S2

Supplementary Table S3

Supplementary Methods

Supplementary Legends

Review Process File