Abstract

For genetic association studies that involve an ordered categorical phenotype, we usually either regroup multiple categories of the phenotype into two categories (“cases” and “controls”) and then apply the standard logistic regression (LG), or apply ordered logistic (oLG) or ordered probit (oPRB) regression which accounts for the ordinal nature of the phenotype. However, these approaches may lose statistical power or may not control type I error rate due to their model assumption and/or instable parameter estimation algorithm when the genetic variant is rare or sample size is limited. Here to solve this problem, we propose a set-valued (SV) system model, which assumes that an underlying continuous phenotype follows a normal distribution, to identify genetic variants associated with an ordinal categorical phenotype. We couple this model with a set-valued system identification algorithm to identify all the key system parameters. Simulations and two real data analyses show that SV and LG accurately controlled the Type I error rate even at a significance level of 10−6 but not oLG and oPRB in some cases. LG had significantly smaller power than the other three methods due to disregarding of the ordinal nature of the phenotype, and SV had similar or greater power than oLG and oPRB. For instance, in a simulation with data generated from an additive SV model with odds ratio of 7.4 for a phenotype with three categories, a single nucleotide polymorphism with minor allele frequency of 0.75% and sample size of 999 (333 per category), the power of SV, oLG and LG models were 70%, 40% and <1%, respectively, at a significance level of 10−6. Thus, SV should be employed in genetic association studies for ordered categorical phenotype.

Keywords: Ordered logistic model, set-valued system identification, multiple thresholds, genetic association study, rare variants

Introduction

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified many genetic variants that are associated with complex diseases over the past decades (Sladek et al., 2007; Welter et al., 2014). Many phenotypes studied in GWAS are either binary or continuous. The logistic regression (LG) and linear regression models are widely used to analyze the binary and continuous phenotype while adjusting for the effects of confounding covariates such as ancestry, age and sex. In cancer GWAS, considerable portion of phenotypes are survival (Innocentiet al., 2012) or relapse (Yang et al., 2012). The Cox proportional hazard regression model(Cox, 1972) and the Fine and Gray hazard rate regression(Fine and Gray, 1999) are the standard methods to analyze survival and relapse outcomes with adjusting for some confounding factors such as ancestry scores, treatment arms, clinical risk or prognostic factors, respectively.

In cancer pharmacogenetics/pharmacogenomics, we are interested in detecting genetic variations influencing drug toxicity or efficacy. The key phenotype referred to as the outcome could be multiple ordinal categories such as dosing of drugs, adverse events scored on scales using ordinal values (1-5) according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events developed by the US National Cancer Institute (Ingle et al., 2010), and effect of treatment on disease such as tumor response in which the metrics of tumor size is categorized as complete response, partial response, stable disease or progressive disease (Wheeler et al., 2013). Furthermore, some ordered phenotype may be defined by splitting a measured continuous variable such as four categories of underweight, normal weight, overweight and obese, based on body index mass, but most of them may be generated due to complicated unobservable or unobserved continuous variables such as the expression level of RNAs or proteins involved in an unknown biological process or stimulated by external environments.

For these ordered phenotypes, researchers often regroup multiple categories into two categories of “cases” and “controls” and then apply the standard LG model (Treviño et al., 2009; Ingle et al., 2010). However, this method may lose substantial power in that re-categorizing the phenotype does not take the ordinal nature of the phenotype into consideration (see Simulation Results section below). The non-parametric method of Spearman rank correlation (Yang et al., 2009) or the Jonckheere–Terpstra tests (Han et al., 2013) which accounts for the ordinal nature of the phenotype can be an attractive method. However, these methods cannot adjust for confounding factors. The parametric method of ordered/ordinal logistic regression (oLG) model (Png et al., 2011) borrows the basic idea of standard LG regression model to avoid these pitfalls. As the most popular model, generalized linear models (GLM), logistic approaches adopt link function of logit form, which brings many advantages. For example, the first derivative and the second derivative of the corresponding log-likelihood function are easy to compute, and the estimated parameter can explain the odds ratio directly. Nevertheless, we still think the logistic approach sometimes is overused. Above all, fitting the response data with the logit link function cannot be justified in many practical applications. The doubt has been confirmed in the case of binary outcome for which probit method has better performance than LG method under non-asymptotic situations (low MAF and small sample size) (Kang et al., 2014). All these two methods will lose statistical power or cannot maintain the type I error rate if the marker is rare and sample size is small due to their model assumptions and/or unstable parameter estimation algorithm. Another parametric method of the ordered probit regression method can also be used but likeoLG, its performance is problematic when the sample size is small and the number of categories is large.

As for traditional system identification, the system input and continuous system output are usually assumed accessible/known. But in some cases, we can only know which set the system output lies in but not the exact continuous output information, which is called set-valued information (Kang et al., 2014). To model the relationship between system input and system output mathematically, a quantization process is adopted to generate the set-valued system from the corresponding continuous latent or unknown variable. Set-valued system identification (SVSI) was first investigated for sensor systems (Wang, et al., 2003). In contrast to the traditional system identification method, SVSI can estimate the model parameters by set-valued information rather than precise output information. It is technically more challenging, but appears in a wide range of applications such as sensor networks and telecommunications (Nair, et al., 2007). Many more motivating examples can be found in Wang et al. (2010). Finite impulse response model is a class of typical linear system model and can be used to approximate many actual physical systems. As an important research branch of SVSI, the identification of finite impulse response model with set-valued data attracts the attention of many researchers and some related results have been obtained (Godoy, et al., 2011; Chen, et al., 2012; Bi, et al., 2014).

In this study, we propose a specific set-valued (SV) system model, which can be considered as a finite impulse response system with set-valued output. The model considers the categorizing process of continuous phenotypes to model the relationship between the ordered outcome and possible genetic or non-genetic explanatory factors in GWAS or next-generation sequencing (NGS) studies. We estimate the parameter of interest by a SVSI approach and use a Wald test statistic for testing the null hypothesis of no association between genetic variant and ordinal phenotype. We perform extensive simulation studies to compare the type I error rate, the power and the computational cost of SV with those of LG, oLG and oPRB methods. Finally, we apply the SV method to the data about minimal residual disease (MRD) in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) (Yang et al., 2009) and the Genetic Analysis Workshop 17 (GAW17) data.

Materials and Methods

Notations

Assume that we have a cohort of N individuals and that the genetic polymorphism of interest is biallelic [e.g., single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)]. The 2 alleles at a SNP are denoted as A and a, where A is the minor allele and together they form three genotypes denoted as AA, Aa, and aa. Suppose that observations (si, Xi, Gi), i = 1, 2, ... N are available, where si is the ordinal disease outcome of individual i; Xi = [xi1, xi2, ..., xim]T is a vector of m covariates that we need to adjust for (e.g., demographic or clinical variables); and Gi = 0, 1, or 2 is the numerical coding corresponding to the three genotypes aa, Aa or AA, respectively, for the ith individual.

The set-valued (SV) model

We propose a novel set-valued (SV) model in which the phenotype information can be regarded as the set-valued observation of a continuous latent variable:

| (1) |

where Gi and Xi represent the genotype and covariates of subject i, yi is the latent continuous variable, f is a deterministic function reflecting the influence of G and X on the latent variable, ei is the random noise, IAk(y) is the indicator function of subset Ak and (r+1) is the total number of categories of the observed outcome. Observed phenotype si is determined based on which set (of sets {Ak, k=0,1,...,r}) the latent variable yi belongs to.

The most common simplified treatment of the set-valued process is to introduce thresholds {c1,c2,…,cr} such that [ck, ck+1). To make the representation concise, we assume that c0 = − ∞, cr+1 = +∞. In this case, SV model is similar to the well-known threshold model. Furthermore, we adopt linear formulation for function f and assume normal distribution for the random noise. The model degenerates to the following:

| (2) |

where ei is the random noise which follows a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a variance of σ2. The null hypothesis of H0: θ = 0 corresponds to no genetic effect of SNP on the phenotype. The parameter θ is to be identified only based on observations (si, Xi, Gi), i=1,2,...,N to test for the null hypothesis using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm below.

In equation (2), if c1=0, then the SV model is the usual ordered probit model. If the ei in equation (2) follows a logistic distribution in equation (2), then the SV model becomes ordered logistic regression (oLG) model (Greene and William, 2003). However, an important deviation from the usual ordered probit regression modeling is that here we take a novel algorithm SVSI to estimate all the key underlying system parameters θ, γ, and c, rather than the iteratively reweighted least squares (IRWLS)algorithm which is usually used in the ordered probit regression. Thus, we call the proposed SV model coupled with the new SVSI algorithm SV and call the usual ordered probit model with IRWLS oPRB throughout the paper to differentiate these two methods due to its better performance below. Without calculating the complicated weighting matrix per iteration, the new algorithm can achieve efficient results with fast computing time. The detailed discussions and results can be seen in results section.

Estimate of θ and test statistic

The system parameters in equation (1) can be estimated by maximizing the likelihood function through the EM algorithm. The estimation process is similar to (Chen, et al., 2012). Denote (θ, γT, α0)T by an overall parameter Θ, by an overall input φi. The core iteration process is as following:

| (3) |

where is the density function and is the cumulative distribution function for a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance σ2 evaluated at . For more details of MLE, see section 1 in the supplementary material.

Suppose the iteration estimator converges to the MLE , the observed Fisher information matrix of (denoted by ) can be obtained according to the following formula (see section 1 in the supplementary material for details)

| (4) |

where L(Θ) is the likelihood function given Θ. Testing for no genetic effect of SNP on the phenotype, that is, H0: θ = 0, can be constructed for the SV method from the Wald statistic

| (5) |

where , the element at the first row and the first column of the inverse Fisher information matrix, represents the estimated variance of . Asymptotically, W is distributed approximately as a central χ2 distribution with 1 degree of freedom under the null hypothesis of no association.

Estimate of threshold C

The estimation of parameters needs the knowledge of threshold vector c=(c1,c2,...,cr).In some situations, the thresholds are available. For example, in leukemia, minimal residual disease (an assessment of decreasing leukemic burden in response to therapy such as chemotherapy for cancer treatment) can be categorized as negative (<0.01%), positive (≥0.01% but <1%) and high-positive (≥1%) using two thresholds of 0.01% and 1% (Yang et al., 2009). In other cases, the latent variable is unobserved and the thresholds are also unknown to us. In the case of binary phenotype, it is very easy to estimate the threshold along with other parameters by dealing with the threshold as a parameter (Kang et al., 2014). But in case of ordered categorical phenotype, we have to estimate them with some techniques. Fortunately, if we presume model parameters as fixed values and threshold as variable, the Hessian matrix of likelihood function is positive definite, which means the likelihood function has a unique maximum point. Here we adopt a switching operation for estimating parameters and thresholds. As for one iteration step, we first estimate model parameters (θ, γT, α0)T based on equation (3), and then estimate the threshold c. Through extensive simulations, gradient descent method shows good performance on the computation time, and is used to estimate the threshold.

| (6) |

The detailed algorithm implementation of the SVSI method is in Supplementary Section 2 and the proposed new SV method has been implemented in an R package which is available for free download from http://www.stjuderesearch.org/site/depts/biostats/software. The simulations adopting SV model and unbiased sampling show that the estimation of parameters and thresholds can converge close to the true value within 10 iterations and complete the convergence process within 100 iterations (see Table S1 and Figure S1).

Simulations

Data generation

We performed extensive simulation studies to evaluate the performance of the proposed SV method against the three competing alternatives including LG for the regrouped binary phenotype (recoding as 0 or greater than 0), oLG, and oPRB. We only considered an ordered phenotype with three categories (si= 0, 1 and 2) in our simulations.

Genotype and covariates simulations

Given the minor allele frequency(MAF) pA, the genotype frequencies p(G=g) were calculated according to Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium(HWE) law, i.e., p(G=0)=(1-pA)2, p(G=1)=2pA(1-pA), p(G=2)=(pA)2. Two covariates were considered, x1as a binary variable that is 1 with a probability of 0.5 and 0 otherwise; and x2 as a continuous variable that follows a standard normal distribution. The genotypes and 2 covariates for a population of 2,000,000 individuals were independently generated from their respective distributions.

Phenotype simulations

The phenotype status was determined from the generated genotype and covariates data according to two models below similar to that for the binary phenotype simulation method by Kang et al., (2014) and Wu et al., (2011):

- LG-based simulation method (LGsimu):

We controlled the proportions of individuals with the ordinal disease outcome s = 2, 1, 0 by α1 and α2 and set it to1:3:6, that is, 10% of individuals have s2, 30% of those have s1 and 60% of those have s0, in the case that all three regression coefficients for SNP, xi1, and xi2 are 0. SV-based simulation method (SVsimu): First a continuous variable was generated from yi=θGi+0.5xi1+0.5xi2+ei, where ei follows a standard normal distribution. Given thresholds (c1,c2), the individuals with a value of yi higher than c2 have phenotype of 2 and ones with a value of yi lower than c1 have phenotype of 0, the remaining have phenotype of 1. We controlled the proportions of individuals with the ordinal disease outcome s = 2, 1, 0 and set it to 1:3:6, that is, 10% of individuals have s2, 30% of those have s1 and 60% of those have s0, in the case that all three regression coefficients for SNP, xi1, and xi2 are 0.

Sample a cohort of N individuals

We select a cohort of N individuals to conduct further association analysis based on the following 2 sampling strategies to mimic two different designs for retrospective and prospective studies:

Randomly sample N/3 individuals per each category (Same): we sample a fixed sample size of N/3 individuals from each category in the population of 2,000,000 individuals to mimic a retrospective design to maximize the power of association testing. Note that this strategy ensures that the sample size must be a multiple of 3, so that for example we may compare results obtained by sampling 999 subjects with the Same strategy to those obtained by sampling 1000 subjects with the Rand strategy described below.

Randomly sample N individuals (Rand): we randomly choose N individuals from the population of 2,000,000 individuals simulated above to mimic a prospective design.

Once the data is generated, for LG, we used glm function in R and fit the glm on the regrouped binary phenotype (new si= 0 if the original si= 0 or new si= 1 if the original si = 1 or 2), genotype and two covariates. For oLG and oPRB, we used polr function in MASS R package and fit polr on the original three-categorical phenotype, genotype and two covariates. Then the Wald test statistic was used for inference for all these three methods to be consistent with the SV method.

Type I error rate simulations

Eight values for MAFs of SNPs were considered: 0.0025, 0.0075, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4 and 0.5. The ordered phenotype was determined from the generated genotype and covariate data by using the two models mentioned above, with θ= 0. To estimate the type I error rate of the SV method, 10,000,000 replicated datasets were simulated for each study, with a small sample size of 1000 (2500) and a large sample size of 2000 (5000) for the Rand sampling method for variants with MAF≥0.0075 (MAF=0.0025) and the corresponding numbers of 999 (2499) and 1998 (5001) for the Same sampling method, respectively. We considered larger significance levels α = 0.05 or 0.01 and stringent genome-wide levels α = 10−5 or 10−6 under the null hypothesis of H0: θ = 0.

Power simulations

Three genetic disease models were considered: additive, dominant, and recessive with their respective genotype coding G (0, 1, 2), (0, 1, 1) and (0, 0, 1) when we simulated the phenotype. The ordered phenotype was determined from the generated genotype and covariate data according to the simulation methods given above, with θ varying from 0.3 to 2 at an increment of 0.1. Datasets were generated 10,000 times for each configuration. The three methods used for the type I error simulations were applied to each data-set, and power was estimated as the proportions of p-values less than α = 10−6.

To mimic a phase II clinical trial, a small sample size of 150 was also used for common variants with MAFs of 0.2 and 0.05 to estimate the power of SV at a significance level of 1×10−4.

Results

Type I error rate

Table 1 shows empirical type I error rates estimated for four methods. Regardless of significance levels, SV correctly maintained type I error control at the given levels for both common and rare variants. LG was conservative for stringent genome-wide levels if SNPs were rare because of large variance of parameter estimate (Table 2) (Kang et al., 2014). oLG and oPRB correctly controlled type I error rate at larger significance levels but did not control type I error rate at stringent genome-wide levels for rare variants when sample size was small because of instability of oLG and oPRB when there are some empty or small cells. Since oPRB cannot control type I error rate at α = 10−6 for rare SNP with MAF 0.0075 and the power of SV is almost identical to that of oPRB in most cases, the power of oPRB was omitted and was not included in the section below.

Table 1.

The ratio of the observed type I error rates of the set-valued (SV), logistic regression (LG and oLG), and the usual ordered Probit (oPRB) methods over the given significance levels α using SVsimu data generation method and random sampling scheme.

| n | p A | 0.05 | 0.01 | 1×10−5 | 1×10−6 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG | SV | oLG | oPRB | LG | SV | oLG | oPRB | LG | SV | oLG | oPRB | LG | SV | oLG | oPRB | ||

| 150 | 0.05 | 0.8 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 1 | 0.37 | 0.9 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0 | 0.4 | 57 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.26 | 560 | 11 |

| 150 | 0.2 | 0.98 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 0.84 | 1.1 | 0.98 | 1 | 0.07 | 1.10 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.48 |

| 2500 | 0.0025 | 0.66 | 0.9 | 0.88 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.69 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0 | 0.16 | 190 | 0.16 | 0 | 0.07 | 1900 | 0.068 |

| 5000 | 0.0025 | 0.9 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.64 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.35 | 0 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 0.12 |

| 1000 | 0.0075 | 0.76 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.31 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.26 | 55 | 0.22 | 0 | 0.1 | 550 | 0.19 |

| 2000 | 0.0075 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.98 | 1 | 0.70 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.34 |

| 1000 | 0.01 | 0.84 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.50 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0 | 0.34 | 4.50 | 0.29 | 0 | 0.2 | 43 | 0.18 |

| 2000 | 0.01 | 0.92 | 1 | 0.98 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.04 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.44 |

| 1000 | 0.05 | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.92 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.39 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.74 |

| 2000 | 0.05 | 1 | 1 | 1.02 | 1 | 0.97 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.69 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| 1000 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1.02 | 1 | 0.97 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.77 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.78 |

| 2000 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1.02 | 1 | 0.99 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.85 | 1.10 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.98 |

n is the number of individuals sampled from the population; pA is minor allele frequency of SNP; LG stands for logistic regression model on the regrouped binary outcome (recoding as 0 or greater than 0); SV stands for the set-valued method; oLG stands for ordered logistic regression method; oPRB stands for the usual ordered probit model with the traditional IRWLS algorithm. Values in bold means inflated type I error rates.

Table 2.

The mean of , mean of estimated standard error of , and standard deviation of across simulation repetitions for the set-valued (SV) and logistic regression (LG and oLG) methods based on 1000 simulations*.

| LG | oLG | SV | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ | SM | DM |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Rand, pA=0.0075 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | LGsimu | H0 | 0.02 | 0.391 | 0.409 | 0.051 | 0.049 | 0.005 | 0.367 | 0.387 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.0017 | 0.219 | 0.231 | 0.008 | 0.007 | |||

| 0.5 | LGsimu | ADD | 0.535 | 0.398 | 0.402 | 1.344 | 1.329 | 0.514 | 0.353 | 0.354 | 1.456 | 1.452 | 0.3039 | 0.212 | 0.213 | 1.43 | 1.426 | |||

| 2 | LGsimu | ADD | 2.229 | 2.711 | 1.336 | 0.822 | 1.669 | 2.009 | 0.366 | 0.374 | 5.49 | 5.374 | 1.1942 | 0.218 | 0.222 | 5.478 | 5.373 | |||

| 0 | SVsimu | H0 | −0.02 | 0.409 | 0.408 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.026 | 0.372 | 0.386 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.016 | 0.221 | 0.229 | −0.073 | −0.071 | |||

| 0.5 | SVsimu | ADD | 0.84 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 1.91 | 1.789 | 0.807 | 0.361 | 0.377 | 2.236 | 2.139 | 0.4834 | 0.217 | 0.226 | 2.231 | 2.139 | |||

| 2 | SVsimu | ADD | 6.953 | 83.61 | 5.785 | 0.083 | 1.202 | 3.442 | 0.711 | 0.648 | 4.841 | 5.31 | 2.0333 | 0.284 | 0.303 | 7.15 | 6.709 | |||

| Rand, pA=0.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | LGsimu | H0 | −0.003 | 0.082 | 0.082 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.004 | 0.078 | 0.078 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.003 | 0.047 | 0.047 | −0.064 | −0.064 | |||

| 0.5 | LGsimu | ADD | 0.502 | 0.085 | 0.087 | 5.941 | 5.798 | 0.5 | 0.076 | 0.077 | 6.566 | 6.477 | 0.2976 | 0.045 | 0.046 | 6.555 | 6.475 | |||

| 2 | LGsimu | ADD | 2.003 | 0.124 | 0.128 | 16.2 | 15.66 | 1.995 | 0.093 | 0.093 | 21.43 | 21.35 | 1.179 | 0.051 | 0.053 | 23.3 | 22.13 | |||

| 0 | SVsimu | H0 | 1E-03 | 0.086 | 0.086 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 1E-06 | 0.079 | 0.078 | 1E-4 | 1E-4 | −2E-4 | 0.047 | 0.046 | −0.004 | −0.004 | |||

| 0.5 | SVsimu | ADD | 0.833 | 0.095 | 0.095 | 8.781 | 8.779 | 0.837 | 0.079 | 0.08 | 10.57 | 10.52 | 0.5012 | 0.047 | 0.047 | 10.76 | 10.57 | |||

| 2 | SVsimu | ADD | 3.581 | 0.221 | 0.214 | 16.19 | 16.73 | 3.418 | 0.132 | 0.129 | 25.84 | 26.59 | 2.0031 | 0.068 | 0.072 | 29.58 | 27.97 | |||

| Same, pA=0.0075 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | LGsimu | H0 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.433 | 0.12 | 0.116 | 0.017 | 0.348 | 0.355 | 0.05 | 0.049 | 0.0103 | 0.211 | 0.216 | 0.049 | 0.048 | |||

| 0.5 | LGsimu | ADD | 0.632 | 0.717 | 0.631 | 0.882 | 1.002 | 0.506 | 0.329 | 0.332 | 1.538 | 1.523 | 0.3091 | 0.2 | 0.202 | 1.543 | 1.532 | |||

| 2 | LGsimu | ADD | 3.042 | 17.62 | 3.062 | 0.173 | 0.993 | 1.939 | 0.338 | 0.333 | 5.74 | 5.816 | 1.174 | 0.195 | 0.193 | 6.035 | 6.091 | |||

| 0 | SVsimu | H0 | 0.004 | 0.442 | 0.46 | 0.009 | 0.008 | −0.002 | 0.362 | 0.369 | −5E-3 | −4E-3 | −8E-4 | 0.217 | 0.221 | −0.004 | −0.004 | |||

| 0.5 | SVsimu | ADD | 0.946 | 1.116 | 0.806 | 0.848 | 1.174 | 0.819 | 0.345 | 0.353 | 2.371 | 2.317 | 0.4936 | 0.206 | 0.21 | 2.392 | 2.348 | |||

| 2 | SVsimu | ADD | 8.881 | 140.8 | 6.375 | 0.063 | 1.393 | 3.368 | 0.493 | 0.86 | 6.836 | 3.917 | 1.9605 | 0.263 | 0.29 | 7.454 | 6.759 | |||

| Same, pA=0.2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | LGsimu | H0 | −0.003 | 0.087 | 0.089 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.005 | 0.074 | 0.074 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.003 | 0.045 | 0.045 | −0.071 | −0.071 | |||

| 0.5 | LGsimu | ADD | 0.548 | 0.091 | 0.089 | 6.011 | 6.169 | 0.5 | 0.073 | 0.072 | 6.853 | 6.92 | 0.3035 | 0.044 | 0.044 | 6.895 | 6.963 | |||

| 2 | LGsimu | ADD | 2.042 | 0.131 | 0.128 | 15.65 | 15.93 | 1.979 | 0.092 | 0.092 | 21.46 | 21.56 | 1.1699 | 0.05 | 0.052 | 23.37 | 22.39 | |||

| 0 | SVsimu | H0 | −0.002 | 0.092 | 0.093 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −1E-03 | 0.076 | 0.077 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −6E-04 | 0.046 | 0.046 | −0.014 | −0.014 | |||

| 0.5 | SVsimu | ADD | 0.871 | 0.101 | 0.098 | 8.615 | 8.866 | 0.833 | 0.078 | 0.075 | 10.68 | 11.04 | 0.4999 | 0.046 | 0.045 | 10.91 | 11.2 | |||

| 2 | SVsimu | ADD | 3.337 | 0.22 | 0.205 | 15.14 | 16.31 | 3.273 | 0.127 | 0.119 | 25.73 | 27.4 | 1.9147 | 0.064 | 0.066 | 29.7 | 28.93 | |||

n=2000 and 1998 for Rand and Same sampling schema.

: The mean of for 1000 replicates; : The mean of estimated standard error of for 1000 replicates; : The empirical standard deviation of for 1000 replicates; pA is minor allele frequency of SNP; θ is the association coefficient of SNP with outcome; SM is simulation model; DM is disease model representing the underlying genetic disease model. LG stands for logistic regression model on the regrouped binary outcome (recoding as 0 or greater than 0); SV stands for the set-valued method; oLG stands for ordered logistic regression method; oPRB is the usual probit model with IRWLS estimation algorithm.

Power of the SV method

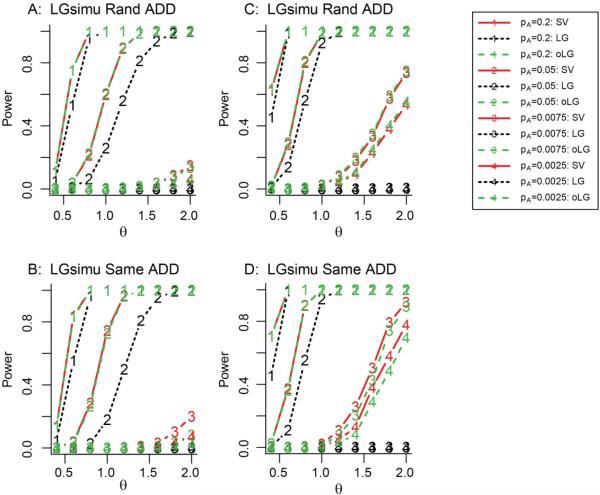

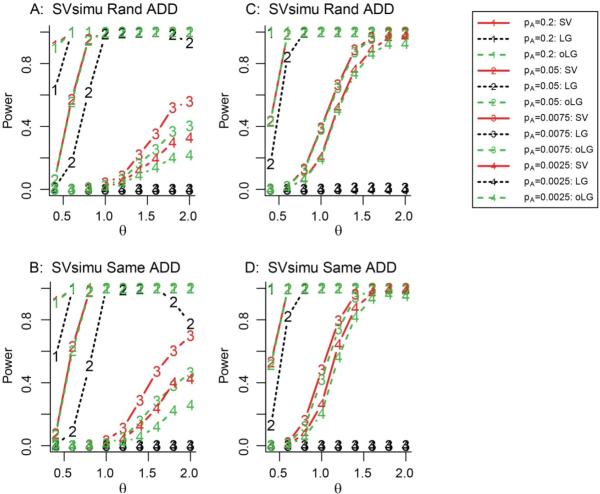

Figures 1–2 show the power of the three methods as a function of effect size (θ) for an additive disease model. As expected, the power of SV and oLG increased with the increase in effect size regardless of distributions of noise, the genetic disease model and sampling methods. The power of three methods was generally higher for Same sampling method than that for Rand sampling method for the same parameter setup. This suggests that for a retrospective design, sampling all individuals with more extreme phenotype is preferred for assessing genetic effect. In some settings, both SV and oLG based on ranked sets performed better than LG based on the regrouped sets. The power difference between them could be more than 50% at a significance level of 10−6 depending on the scale of the sample size. As expected, for a SNP with MAF of 0.05, given a sample size of 1000 with Rand and 999 with Same, the power of LG for the regrouped binary outcome first increased to 100%, then decreased with increase in effect size (Figure 2A-2B). The drop of the power of LG method for the very large effect size given a small fixed sample size and a SNP with small MAF is due to the high probability of absence of individuals with phenotype 0 and carrying minor alleles (see population 3×3 tables in Supplementary matrix 1 for θ = 1 and 2, respectively), which leads to a very large estimated standard error of by LG. For example, given N = 999, for θ = 1, 0 out of 1000 simulated datasets had absence of individuals with phenotype 0 and carrying minor alleles so that the mean and the standard deviation of were 2.024 and 0.258 which leaded to a standardized effect size of . However, for θ θ = 2, 58 out of 1000 simulated datasets had absence of individuals with phenotype 0 and carrying minor alleles so that the mean and the standard deviation of were 4.50 and 3.288 which leaded to a standardized effect size of which is much smaller than that for θ = 1. Below we will focus on power comparison between SV and oLG. The power gain for the new SV method was noticeable in detecting rare variants especially when the individuals was sampled using Same sampling method from the population generated using SVsimu (Figures 1-3).

Figure 1. Power of SV method for the additive model using LGsimu simulation method.

Panels A and B show sample sizes of N=1000 (999) and 2500 (2499) for common and rare variants, respectively. Panels C and D show sample sizes of N=2000 (1998) and 5000 (5001) for common and rare variants, respectively. The solid, dotted and dash lines correspond to the SV, LG and oLG methods, respectively. The numbers of 1-4 correspond to the tested SNPs with MAFs of 0.2, 0.05, 0.0075 and 0.0025, respectively. The significance level of the test was 1×10−6.

Figure 2. Power of SV method for the additive model using SVsimu simulation method.

Panels A and B show sample sizes of N=1000 (999) and 2500 (2499) for common and rare variants, respectively. Panels C and D show sample sizes of N=2000 (1998) and 5000 (5001) for common and rare variants, respectively. The solid, dotted and dash lines correspond to the SV, LG and oLG methods, respectively. The numbers of 1-4 correspond to the tested SNPs with MAFs of 0.2, 0.05, 0.0075 and 0.0025, respectively. The significance level of the test was 1×10−6.

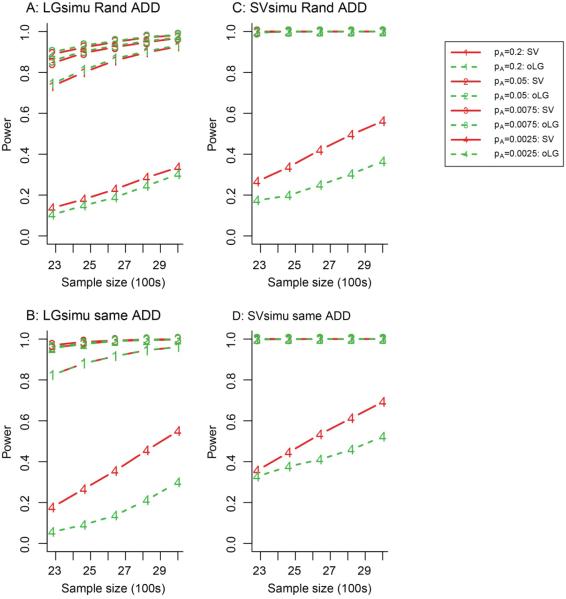

Figure 3. Power of SV method as a function of sample size.

The left and right panels show LGsimu and SVsimu, respectively. The x-axis is the sample size divided by 100. The solid and dash lines correspond to the SV and oLG methods, respectively. The numbers of 1-4 correspond to the tested SNPs with MAFs of 0.2, 0.05, 0.0075 and 0.0025, respectively. The significance level of the test was 1×10−6. θ values were 0.4, 0.8, 2 and 2.4 for SNPs with MAFs of 0.2, 0.05, 0.0075 and 0.0025, respectively.

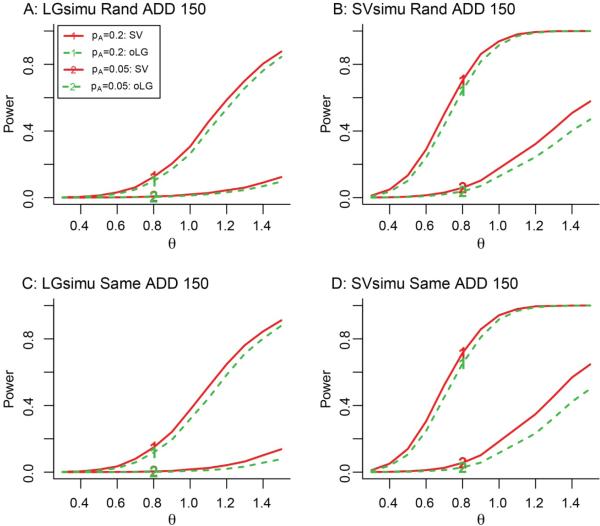

For a common SNP with an MAF of 0.2 or 0.05, the power of SV appeared to be similar to or higher than that of oLG depending on the scale of sample size, regardless of the genetic disease models, sampling methods and distributions of noise (Figures 1-2, and 4). Surprisingly, with a small sample size of N=150, for a SNP with a MAF of 0.2 and θ = 0.7, the power difference between SV and oLG was 8% (Figure 4B and 4D). But for a SNP with a MAF of 0.05 and θ = 1.5, the power difference between SV and oLG was 15% (Figure 4B and 4D).

Figure 4. Power of SV method for detecting common variants using 150 individuals under the additive model.

The left and right panels show phenotype simulation methods of LGsimu and SVsimu, respectively. The solid and dash lines correspond to the SV and oLG methods, respectively. The numbers of 1-2 correspond to the tested SNPs with MAFs of 0.2 and 0.05, respectively. The significance level of the test was 1×10−4. The legends of panels BD are the same as that of panel A.

For a rare SNP with an MAF of 0.0075 or 0.0025, if the noise follows a logistic distribution, with Rand sampling method, the power of oLG was almost identical to or slightly higher than that of SV, regardless of genetic disease models (Figure 1A-1C). However, interestingly, with Same sampling method, the power of SV was slightly or much higher than that of oLG, regardless of genetic disease models (Figure 1B-1D). For example, for a SNP with MAF of 0.0075, θ = 2 (equivalent to OR=eθ=7.4), and N=999, the power difference was 12% between oLG and SV (Figure 1B). Similarly, for a SNP with MAF of 0.0025, θ = 1.8 (equivalent to OR=eθ=6), and N=5001, the power difference was 10% between oLG and SV (Figure 1D). If the noise follows a normal distribution, regardless of sampling methods, the power of SV was generally higher than that of oLG (Figure 2). The power difference between oLG and SV became larger at larger effect size and smaller sample sizes. For example, for a SNP with MAF of 0.0075, θ = 2, and N=999, the power difference was 24%between oLG and SV (Figure 2A). Similarly, for a SNP with MAF of 0.0025, θ = 2, and N=1000, the power difference was 17% between oLG and SV (Figure 3B). These results indicate that for rare genetic variant association studies, we strongly recommend SV be employed instead of LG and oLG if the phenotype was defined from a continuous normal distribution.

Figure 3 displays the power of the SV and oLG methods as a function of sample size for the additive disease model. As expected, the power of two methods increased with an increase in sample size. For a common SNP with an MAF of 0.2 or 0.05 and an effect size of 0.4 or 0.8, respectively, the power of SV was almost identical to that of oLG, regardless of the distributions of noise, sample size, disease models and sampling methods (Figure 3). For a rare SNP with a MAF of 0.0075 or 0.0025 and an effect size of 2 or 2.4, if the noise follows a logistic distribution and a Rand sampling method is used, the power of SV appeared to be similar to that of oLG, regardless of the disease models (Figure 3A) but the power of SV was much larger than that of oLG for a Same sampling method (Figure 3B). The power difference became larger with moderate sample sizes. If the noise follows a normal distribution, regardless of sampling method, the power of SV was much greater than that of oLG but depending on the sample size (Figure 3C-3D).

Variance of the genetic association parameter estimate

Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2S gives the mean of , mean of estimated standard errors of , and standard deviations of across simulation repetitions for the LG, SV and oLG methods based on 1,000 simulation repetitions. Data were generated using the same parameter setup as given in Table 1 and Figures 1–4.

The mean of estimated standard error of appeared to be close to its standard deviation for the SV method in all simulation setups but not for LG, oLG and oPRB (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2S). Interestingly, when SNP is rare (pA=0.0075) and association parameter is large (θ=2), the means of estimated standard errors of for the oLG and LG method were much larger than their standard deviations, especially when the sample size was small, which leads to their significant power loss compared with RV and oPRB. This is not surprising since in this setting, there is a high probability of absence of individuals with phenotype 0 and carrying minor alleles, which leads to a very large estimated standard error of .

We also calculated the ratio of the mean of over the mean of estimated standard error of , i.e, , and the ratio of the mean of to the standard deviation of , i.e, , which were used to mimic the standardized effect sizes to make the estimates a comparable scale and was used to compare different models (Table 2 and supplementary Table 2S). Under the null hypothesis, no matter what the phenotype simulation model, sampling method, MAF and sample size, both standardized effect sizes with SV were very close and both were close 0 which showed that SV could control type I error rate but not for oLG. Under some extreme situations such as small sample size and rare SNP, was higher than for oLG but both would be close to 0 as sample size increased. Under the alternative hypothesis, in most cases SV had the “standardized effect sizes” similar to oLG both were much larger than LG which further demonstrates that SV had the power similar to oLG both had larger power than LG in most cases. Under some extreme situations, rare SNP, small sample size or large effect size, SV had higher “standardized effect sizes” than oLG, which clearly demonstrated the power gain of SV compared with LG and oLG for these settings. All these simulation results obviously demonstrate that SV can give more efficient, more robust and much less variable than oLG. In particular, it dominates others under small sample sizes and rare variants.

We also recorded the computing time for each of the four methods above as implemented in R and Matlab for the simulated data. In Matlab, SV was typically about twice as fast as oPRB and oLG but was similar to LG. In R, SV, oPRB, and oLG had similar run times with SV tending to be slightly slower than oLG but all was slower than LG (Supplementary materials section 3 and Table 3S). These are consistent with the results reported by Bi et al. (2014).

Application to the top 25 SNPs of MRD in ALL

ALL is the most common type of cancer in children and the cure rate is more than 80% but there exists considerable inter-individual variability in therapy response (Yang et al., 2009). Genetic variants of SNPs in the interleukin 15 (IL15) gene and other SNPs associated with risk of MRD at the end of induction therapy have been reported recently (Yang et al., 2009). We analyzed the top 25 SNPs identified by Spearman rank correlation test in childhood ALL in two independent populations: 318 patients in St Jude Total Therapy protocols XIIIB and XV (Pui et al., 2004, 2009), and 169 patients in Children's Oncology Group (COG) trial P9906 (Borowitz et al., 2003). For St Jude patients, MRD status was categorized as negative (<0.01%), positive (≥0.01% but <1%), and highpositive (≥1%). For COG patients, MRD status was similarly categorized as: negative (≤0.01%), positive (>0.01%, but ≤1%), and high-positive (>1%).

Table 3 shows association results for the top 25 SNPs in both and combined cohort of St Jude and COG. At a significance level of 0.05/25 = 0.002, in the combined cohorts, 24 SNPs were found statistically significant by LG, oLG and oPRB but 23 of them were detected by SV; for St. Jude cohorts, LG, oLG, oPRB and SV found 10, 9, 9, and 8 SNPs statistically significant, respectively, where 5 were detected by all four methods; for COG cohorts, LG, oLG, oPRB and SV found 8, 8, 7 and 8 SNPs statistically significant, respectively, where 6 were detected by all four methods. There were only one SNP (SNP_A-1794325) detected by all our methods in both SJ and COG cohorts. Overall, the p-values for all four methods were comparable. Based on these results it seems that all four methods perform similarly. However, we know that the distribution of the continuous MRD measure at the end of induction therapy was right-skewed and definitely not following a normal distribution especially for ALL (Moppett et al., 2003). More importantly, we do not know what are the true SNPs associated with MRD in ALL.

Table 3.

P-values of association tests between SNPs and minimal residual disease in St. Jude and COG cohorts

| SJ | COG | Combined | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | LG | oLG | oPRB | SV | LG | oLG | oPRB | SV | LG | oLG | oPRB | SV |

| SNP_A-1709114 | 0.0086 | 0.0059 | 0.0055 | 0.006 | 0.0024 | 0.00171 | 0.00286 | 0.003 | 6.67×10−6 | 1.27×10−6 | 2.27×10−6 | 2.85×10−6 |

| SNP_A-1793591 | 0.0015 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | 0.0012 | 0.0181 | 0.01411 | 0.01675 | 0.017 | 5.15×10−6 | 1.03×10−6 | 2.55×10−6 | 2.64×10−6 |

| SNP_A-1794325 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 0.001 | 0.0011 | 0.0003 | 0.00017 | 0.00031 | 3×10−4 | 5.74×10−8 | 1.43×10−8 | 4.44×10−8 | 4.31×10−8 |

| SNP_A-1807959 | 0.0119 | 0.0131 | 0.0186 | 0.0295 | 0.001 | 0.00128 | 0.00211 | 0.002 | 4.96×10−6 | 3.64×10−6 | 8.79×10−6 | 1.29×10−5 |

| SNP_A-1892341 | 0.0045 | 0.0062 | 0.0157 | 0.018 | 0.0002 | 9.45×10−5 | 8.59×10−5 | 1×10−4 | 3.38×10−7 | 7.17×10−8 | 1.92×10−7 | 3.96×10−7 |

| SNP_A-1918014 | 0.0022 | 0.0039 | 0.0107 | 0.0113 | 0.0081 | 0.00808 | 0.0086 | 0.011 | 4.70×10−5 | 8.23×10−5 | 0.00023 | 0.00028 |

| SNP_A-1958136 | 0.0017 | 0.0023 | 0.0051 | 0.0053 | 0.0124 | 0.00993 | 0.00849 | 0.009 | 2.18×10−5 | 2.35×10−5 | 3.36×10−5 | 3.55×10−5 |

| SNP_A-1980357 | 0.0104 | 0.0159 | 0.0414 | 0.0457 | 0.0073 | 0.00734 | 0.00995 | 0.018 | 7.26×10−5 | 0.00025 | 0.00123 | 0.00181 |

| SNP_A-1988256 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.0008 | 0.0009 | 0.0274 | 0.01297 | 0.01552 | 0.017 | 3.47×10−5 | 1.96×10−5 | 6.82×10−5 | 8.78×10−5 |

| SNP_A-2044445 | 0.0104 | 0.0051 | 0.0017 | 0.0019 | 0.0078 | 0.00226 | 0.00215 | 0.00195 | 0.00013 | 1.73×10−5 | 6.74×10−6 | 6.47×10−6 |

| SNP_A-2062945 | 0.0006 | 0.0007 | 0.0017 | 0.0018 | 0.001 | 0.00216 | 0.00277 | 0.003 | 4.12×10−7 | 8.67×10−7 | 2.46×10−6 | 3.02×10−6 |

| SNP_A-2105458 | 0.0015 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | 0.3138 | 0.0274 | 0.01297 | 0.01552 | 0.171 | 7.74×10−5 | 9.51×10−6 | 2.88×10−5 | 0.08431 |

| SNP_A-2139851 | 0.005 | 0.0072 | 0.0154 | 0.0176 | 0.0031 | 0.00348 | 0.00562 | 0.007 | 1.26×10−5 | 1.39×10−5 | 4.85×10−5 | 7.62×10−5 |

| SNP_A-2172039 | 0.0027 | 0.0023 | 0.0029 | 0.003 | 0.0335 | 0.00424 | 0.00186 | 0.0016 | 0.00059 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 9.40×10−5 |

| SNP_A-2174556 | 0.0005 | 0.0007 | 0.002 | 0.0022 | 0.0045 | 0.00559 | 0.00844 | 0.009 | 2.37×10−6 | 3.93×10−6 | 1.47×10−5 | 1.96×10−5 |

| SNP_A-2184177 | 0.0033 | 0.003 | 0.0029 | 0.0025 | 0.0056 | 0.00565 | 0.00564 | 0.006 | 2.85×10−5 | 2.28×10−5 | 2.29×10−5 | 1.99×10−5 |

| SNP_A-2207718 | 0.0077 | 0.0036 | 0.0012 | 0.0014 | 0.0093 | 0.00256 | 0.00239 | 0.002 | 0.00011 | 1.32×10−5 | 5.23×10−6 | 5.18×10−6 |

| SNP_A-2261153 | 0.0055 | 0.0049 | 0.0064 | 0.036 | 0.9885 | 0.00482 | 0.00319 | 0.278 | 0.00319 | 0.00244 | 0.00307 | 0.04401 |

| SNP_A-2264953 | 0.0008 | 0.0008 | 0.0013 | 0.0026 | 0.0001 | 8.8×10−5 | 0.00016 | 1×10−4 | 2.77×10−8 | 7.47×10−9 | 2.24×10−7 | 3.27×10−8 |

| SNP_A-4233826 | 0.0018 | 0.0019 | 0.0031 | 0.0032 | 0.0002 | 0.00032 | 0.00055 | 8×10−4 | 1.26×10−7 | 6.62×10−8 | 3.30×10−7 | 4.47×10−7 |

| SNP_A-4234252 | 0.016 | 0.0207 | 0.0362 | 0.0403 | 0.9843 | 0.01177 | 0.0057 | 0.015 | 0.00079 | 0.00047 | 0.00069 | 0.00116 |

| SNP_A-4236270 | 0.0013 | 0.001 | 0.0007 | 0.0008 | 0.0022 | 0.00348 | 0.0049 | 0.005 | 1.09×10−5 | 1.15×10−5 | 1.45×10−5 | 1.89×10−5 |

| SNP_A-4244750 | 0.0051 | 0.0035 | 0.0032 | 0.0031 | 0.0134 | 0.00518 | 0.0055 | 0.006 | 0.00056 | 0.0003 | 0.00031 | 0.00032 |

| SNP_A-4249789 | 0.0333 | 0.0335 | 0.0416 | 0.0415 | 0.0011 | 0.0007 | 0.00054 | 9×10−4 | 1.83×10−5 | 6.87×10−6 | 6.51×10−6 | 8.98×10−6 |

| SNP_A-4272973 | 0.0029 | 0.0024 | 0.002 | 0.0019 | 0.0011 | 0.00041 | 0.00036 | 3×10−4 | 2.07×10−5 | 1.05×10−5 | 7.43×10−6 | 6.72×10−6 |

LG stands for logistic regression model on the regrouped binary outcome (recoding as 0 or greater than 0); SV stands for the set-valued method; oLG stands for ordered logistic regression method; oPRB is the usual probit model with IRWLS estimation algorithm. The p-values in bold showed statistically significant at a significance level of 0.002.

Application to the Mini-Exome Data of Genetic Analysis Workshop 17

To further evaluate the performance of the proposed SV method, we analyzed data from the Genetic Analysis Workshop 17 (GAW17) which contained “mini-exome” sequence genotype data of 24,487 SNPs in 3,205 genomic regions of 697 unrelated individuals provided by the 1000 Genome Project [27]. Three quantitative phenotypes (Q1, Q2, and Q4) were simulated from the normal distribution. Q1 was influenced not only by genetic variant, but also environmental variables, and gene-environmental interactions. Q2 was only influenced by genetic variants not environmental variables. Q4 was influenced only by the environments and not genetic variants. Here we only analyzed Q2 since there were no environments and gene-environments interactions associated with Q2. Q2 was influenced by 72 SNPs in 13 genes. Furthermore, 200 replicate datasets were generated for each phenotype, using one fixed genotype data. To apply our methods to GAW17 data, we classified Q2 to the ordered categorical phenotype using Φ−1(0.9) and Φ−1(0.6) as two thresholds and then analyzed them by mimicking we do not know Q2 which is the same as our SV model. First, quality control analysis was performed on the SNPs and SNPs with MAFs less than 0.0086 or HWE test p-values less than 0.00001 were excluded. There were 8387 SNPs remaining in the association analysis of Q2. The reclassified ordered categorical phenotype for the 1st, 10th, 100th and 200th replicate data was used as our outcomes (supplementary Table S3 for frequency table and Figure S2 for the histograms) and included age, gender, and smoking status as covariates in all four methods above.

Table 4 shows the association analyses results for Q2. At a significance level of 0.00001, for the 1st replicate data, there was no SNP found statistically significant by using SV and LG but there were 112 no-causal SNPs found statistically significant by using oLG and oPRB, which was similar to the 10th replicate data. For the 200th replicate data, at a level of 0.00001, no SNP was found statistically significant by any of the four methods. For the 100th replicate data, SV and LG only found one true causal SNP but did not detect no-causal SNPs. oLG and oPRB also found the same true causal SNP but simultaneously found 99 no-causal SNPs whose p-values were 0. At a significance level of 0.0005, SV found more true causal SNPs than and similar no-causal SNPs to LG. SV found similar true causal SNPs to but much less no-causal SNPs than oPRB and oLG. GAW17 data analyses showed that SV had similar or higher power than oLG and oPRB but the latter cannot maintain the type I error rate. They were consistent with and further supported our extensive simulation results above.

Table 4.

The number of SNPs truly and falsely associated with Q2 for GAW17 data with p-values less than different significance level α

| 1st | 10th | 100th | 200th | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SV | LG | oLG | oPRB | SV | LG | oLG | oPRB | SV | LG | oLG | oPRB | SV | LG | oLG | oPRB | |||||||||||||||||

| α | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP |

| 5×10−4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 112 | 1 | 112 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 113 | 0 | 116 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 100 | 1 | 101 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 12 |

| 1×10−4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 0 | 112 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 111 | 0 | 111 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 99 | 1 | 99 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| 5×10−5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 0 | 112 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 111 | 0 | 111 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 99 | 1 | 99 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 1×10−5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 0 | 112 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 110 | 0 | 110 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 99 | 1 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

LG stands for logistic regression model on the regrouped binary outcome (recoding as 0 or greater than 0); SV stands for the set-valued method; coLG stands for ordered logistic regression method; oPRB is the usual probit model with IRWLS estimation algorithm. TP is the true positive; FP: the false positive;

Discussion

With the availability of data from whole-genome sequencing and whole-exome sequencing studies in which small or moderate sample sizes are used due to the high cost of sequencing technology (Lanktree et al., 2010; Emond et al., 2012) and/or the rare diseases in cancer pharmacogenomics studies such as pediatric cancers of retinoblastoma and Ewing's (Gurney et al., 1995; Wheeler et al., 2013), there is an increasing demand for the development of powerful and robust association testing procedures for identifying genetic variations associated with an ordered multiple responses phenotype of interest. In this study, we propose a new SV system that models the relationship between an ordered phenotype and genetic variants and introduce an SVSI approach to testing the genotype-ordered categorical phenotype association. To be more detailed, the simplified SV model assumed the system noise following a normal distribution. The normal distribution assumption is considered reasonable because it is in accordance with the classical central limit theory. And after a simple transformation, we find the logistic approach is also a specified form of SV model, and the diversity is that the system noise is slightly different from the normal distribution. The diversity is so subtle that the corresponding results show tiny difference under asymptotic situations, i.e. common MAF and/or large sample size. Under non asymptotic situations, i.e. low MAF and/or small sample size, it is inevitable to suffer power loss for every statistical method. And the degree of power loss depends largely on the underlying assumptions. Through simulations, we found that both LG and oLG methods suffered obvious power loss because of high variance of estimated parameter and that oPRB and oLG could not control type I error at a stringent significance level. While the SV method sustained a better performance in these situations due to the normal distribution of the noise term compared to the logistic distribution with heavier tails as well as the updated computationally efficient and robust EM algorithm.

The statistical methods based on model are the most effective when the model is in accordance with actual data. Invalid model assumption will bias the results more or less. Hence, we think it is very important to compare two methods under their own model assumptions. Simulations and real data applications show that the proposed SV method has a robust performance for testing association between ordered phenotypes and genetic variations regardless of the logistic or normal distributions of noise and genetic disease models, and that generally outperforms the commonly used LG model, and oLG especially when the SNP is rare and when the sample size is limited. Thus, we recommend the use of the SV approach instead of the LG or oLG model, to identify genetic variants in genetic association studies for ordered phenotypes. Although not reported here, simulation studies showed similar results for the dominant and recessive disease models and for a common SNP with MAFs such as 0.1, 0.3, 0.4 or 0.5.

When we estimate the parameters using the system identification method, we suppose that the variance of noise is known as 1 because we are interested in testing genotypephenotype associations not estimating the effect size of association. In real data analysis, the true variance of noise is usually unknown and also may not be equal to 1 which will definitely affect the power of the LG, oLG and SV. By simulations, not surprisingly, as the true variance is bigger (smaller) than 1, the power of all three methods will decrease (increase). However, as expected, the power of the SV method is still identical to or higher than that of oLG and both are much higher than that of LG (data not shown). If the distribution of underlying noise is neither normal distribution nor logistic distribution, for example, t-distribution, simulation results show the same conclusion. Thus, conclusions about the power gain of the SV compared to LG and oLG is robust to the logistic, normal and t distribution of the underlying noise. In addition, if we are interested in estimating the association effect size of SNP on the phenotype, the noise variance parameter can also be estimated along with other parameters using generalized expectation maximization algorithm (Godoy et al., 2011). We have implemented the proposed new SV method in an R package which is available for free download from http://www.stjuderesearch.org/site/depts/biostats/software. The method can be easily applied to candidate gene association analysis, GWAS or NGS studies with hundreds or thousands of individuals for ordered categorical phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the American Lebanese and Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (11171333 and 61134013), National Science Foundation (DMS-1209112) and National Institutes of Health (R01 HG006292). The Genetic Analysis Workshop is supported by the NIH grant R01 GM031575. We thank Dr. Xueyuan Cao for providing the ALL data and Dr. Dario Campana for collecting the original MRD data at SJ. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments which have significantly improved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- Bi W, Zhao Y. Iterative parameter estimate with batched binary-valued observations: convergence with an exponential rate. Proceedings of the 19th International Federation of Automatic Control World Congress. 2014;19:3220–3225. [Google Scholar]

- Borowitz MJ, Pullen DJ, Shuster JJ, et al. Children's Oncology Group study. Minimal residual disease detection in childhood precursor-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: relation to other risk factors: a Children's Oncology Group study. Leukemia. 2003;17(8):1566–1572. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Zhao Y, Ljung L. Impulse response estimation with binary measurements: are gularized FIR model approach system identification. 16th IFAC Symposium on System Identification. 2012;16(1):113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;4:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Emond MJ, Louie T, Emerson J, Zhao W, Mathias RA, Knowles MR, Wright FA, Rieder MJ, Tabor HK, Nickerson DA. Exome sequencing of extremephenotypesidentifiesDCTN4 as a modifier of chronic Pseudomonasaeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2012;44(8):886–889. doi: 10.1038/ng.2344. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy B, Goodwin G, Aguero J, Marelli D, Wigren T. On identification of FIR systems having quantized output data. Automatica. 2011;47:1905–1915. [Google Scholar]

- Greene William H. Econometric Analysis. fifth edition Prentice Hall; 2003. pp. 736–740. [Google Scholar]

- Gurney JG, Severson RK, Davis S, Robison LL. Incidence of cancer in children in the United States. Sex-, race-, and 1-year age-specific rates by histologic type. Cancer. 1995;75:2186–95. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950415)75:8<2186::aid-cncr2820750825>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Shin ES, Lee YS, Ghang HY, Kim SY, Hwang JA, Kim JY, Lee JS. A genome-wide association study for irinotecan-related severe toxicities in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Pharmacogenomics J. 2013;13:417–22. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2012.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingle JN, Schaid DJ, Goss PE, Liu M, Mushiroda T, Chapman JA, Kubo M, Jenkins GD, Batzler A, Shepherd L. Genome-wide associations and functional genomic studies of musculoskeletal adverse events in women receiving aromatase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4674–4682. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5064. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti F, Innocenti F, Owzar K, Cox NL, Evans P, Kubo M, Zembutsu H, Jiang C, Hollis D, Mushiroda T, Li L. A genome-wide association study of overall survival in pancreatic cancer patients treated with gemcitabine in CALGB 80303. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:577–584. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1387. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang G, Bi W, Zhao Y, Zhang JF, Yang JJ, Xu H, Loh ML, Hunger SP, Relling MV, Pounds S, Cheng C. A new system identification approach to identifying genetic variants in sequencing studies for a binary phenotype. Human Heredity. 2014;78:104–116. doi: 10.1159/000363660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanktree MB, Hegele RA, Schork NJ, Spence JD. Extremes of unexplained variation as a phenotype: an efficient approach for genome-wide association studies of cardiovascular disease. CircCardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:215–221. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.934505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moppett J, Burke GAA, Steward CG, Oakhill A, Goulden NJ. The clinical relevance of detection of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:249–253. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.4.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair GN, Fagnani F, Zampieri S, Ecans RJ. Feedback control under data rate constraints: an overview. Proceedings of the IEEE. 2007;95(1):108–137. [Google Scholar]

- Pui CH, Sandlund JT, Pei D, et al. Total Therapy Study XIIIB at St Jude Children's Research Hospital. Improved outcome for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of Total Therapy Study XIIIB at St Jude Children's Research Hospital. Blood. 2004;104(9):2690–2696. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D, Bowman WP, Sandlund JT, Kaste SC, Ribeiro RC, Rubnitz JE, Raimondi SC, Onciu M. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2730–2741. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900386. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Png E, Thalamuthu A, Ong RT, Snippe H, Boland GJ, Seielstad M. A genome-wide association study of hepatitis B vaccine response in an Indonesian population reveals multiple independent risk variants in the HLA region. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(19):3893–3898. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladek R, Rocheleau G, Rung J, Dina C, Shen L, Serre D, Boutin P, Vincent D, Belisle A, Hadjadj S. A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;445:881–885. doi: 10.1038/nature05616. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treviño LR, Shimasaki N, Yang W, Panetta JC, Cheng C, Pei D, Chan D, Sparreboom A, Giacomini KM, Pui CH. Germline genetic variation in an organic anion transporter polypeptide associated with methotrexate pharmacokinetics and clinical effects. J ClinOncol. 2009;27(35):5972–5978. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4156. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Yin G, Zhang J, Zhao Y. System identification with quantized observations. Birkhauser. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhang J, Yin G. System identification using binary sensors. IEEE TAC. 2003;48(11):1892–1907. [Google Scholar]

- Welter D, MacArthur J, Morales J, Burdett T, Hall P, Junkins H, Klemm A, Flicek P, Manolio T, Hindorff L, Parkinson H. The NHGRI GWAS Catalog, a curated resource of SNP-trait associations. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42(Database issue):D1001–D1006. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler HE, Maitland ML, Dolan ME, Cox NJ, Ratain MJ. Cancer pharmacogenomics: strategies and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(1):23–34. doi: 10.1038/nrg3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MC, Lee S, Cai T, Li Y, Boehnke M, Lin X. Rare-variant association testing for sequencing data with the sequence kernel association test. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(1):82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JJ, Cheng C, Devidas M, Cao X, Campana D, Yang W, Fan Y, Neale G, Cox N, Scheet P. Genome-wide association study identifies germline polymorphisms associated with relapse of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120(20):4197–4204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-440107. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JJ, Cheng C, Yang W, Pei D, Cao X, Fan Y, Pounds S, Treviño LR, French D, Campana D. Genome-wide interrogation of germline genetic variation associated with treatment response in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2009;301(4):393–403. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.7. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.