Abstract

Objective

PHRs may address the needs of children with ADHD. Among parents, we assessed acceptance, barriers, and intentions regarding use of PHR for their children with ADHD.

Methods

Survey of parents from three practices in Rochester NY. Stepwise logistic regression analysis explored factors predicting respondents’ intentions for future use of PHR, accounting for care coordination needs, caregiver education, SES and satisfaction with providers.

Results

Of 184 respondents, 23% had used the PHR for their child, 82% intended future use. No difference was observed between users and non-users regarding gender, age, race, or education. Users were more likely than non-users to reside in the suburbs (p=0.03). Caregivers were more likely to plan future use of the PHR if they felt engaged as partners in their child’s care (AOR 2.3, 95%CI 1.2, 4.5).

Conclusions

Parents are enthusiastic about PHRs. Future work should focus on engaging them as members of the healthcare team.

Keywords: ADHD, Personal Health Records, patient centered care, health service needs

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), the most common behavioral disorder managed in pediatric primary care, affects approximately 10% of U.S. children.1,2 Optimal management of ADHD requires frequent communication among parents, educators, and healthcare providers to coordinate environmental, behavioral, and medication interventions that are systematic and goal-directed.3 Poorly-managed or fragmented care of children with ADHD increases risks of unintentional injury, educational underachievement, and impaired interpersonal relationships4–7, and burdens their families and communities with near- and long-term costs.8–15 Low-income children with ADHD are especially vulnerable to care fragmentation, particularly in settings with inadequate care coordination services.16

In contrast, well-organized care for children with ADHD improves child functioning and decreases adverse events at home, in school, and in the community. In 2011, the American Academy of Pediatrics endorsed the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) as the preferred model to organize care of children with ADHD.3 Children receiving care in PCMHs are more likely to receive medication and less likely to have difficulties participating in activities, making friends, or attending school.17–20 Ideally, children’s care within a PCMH is led by personal doctors or nurses who know them well, provide consistent health care settings, and support care coordination and necessary referrals. In this structure, ADHD management can be tailored to the needs of children and their families, and integrated with efforts of mental health providers, social support services, and other needed specialists.2

Clinical decision tools integrated with electronic health records (EHR) and electronic personal health records (PHR) which parents can access from home or other settings have been proposed as promising strategies supporting care-coordination to manage children with chronic illnesses. EHR-based decision support has demonstrably improved the likelihood that children with ADHD receive care that meets national guidelines for ADHD-specific visits and interval management.21 Electronic PHR-based tools have the potential to extend those EHR-based tools by helping providers deliver personalized health information resources to parents outside office encounters, while giving parents convenient access to medication refills, appointment scheduling, and information exchange with providers. PHRs may also empower patients, improve care coordination, and support medical homes through tools for home monitoring and self-management.22 Therefore, they may provide significant benefits for children with ADHD.

However, very few PHRs have been developed or evaluated for pediatric patients and their families,23,24 including families dealing with ADHD. Despite the recent proliferation of PHR platforms and types, the literature shows persistently low levels of awareness of PHRs by patients and caregivers, and low levels of preparedness by providers for active engagement with PHRs.25

This study focused on parents of children with ADHD, and aimed to: (1) assess parent acceptance of and barriers to use of PHRs and PHR-based tools, such as web-based monitoring scales, symptom checklists, and requests for medication refills; and (2) obtain caregiver input about best uses of PHR-based tools in the management of their children with ADHD.

Methods

Overview

We conducted a cross-sectional mixed-mode survey (by mail, internet, and telephone) to explore caregiver attitudes, intentions, and preferences regarding PHR use for management of their child’s ADHD.

Participating Practices

We recruited three primary care practices that use the EPIC™ electronic health record (eRecord™) and its integrated PHR, MyChart™ . All three practices are academic affiliates of the University of Rochester and serve as continuity clinic sites for resident training. This study was reviewed and approved by the Research Subjects Review Board of the University of Rochester Medical Center.

At the time of the study, MyChart™ had been available to all adult patients (18 years of age and older) at all three sites for at least 6 months. Proxy access to MyChart™ was available to legal guardians of children from birth through 11 years after confirmation of eligibility by practice staff. All adolescents (ages 12 through 17) had the option of granting proxy access to adult caregivers. Available features included appointment scheduling, secure emails to provider, refill requests, non-sensitive laboratory results, immunization records, and appointment reminders.

Subjects and Sample Size

Inclusion criteria were: child age 5 through 11 years at time of survey; presence of ADHD on problem list; and at least one encounter for ADHD within the previous 2 years. If more than one child in a given household met inclusion criteria, the child with the birth date closest to the date of sample selection was eligible. The respondent was the adult person (minimum age 18 years) primarily responsible the child’s health care. No additional exclusion criteria were used.

Of the entire eligible population of 1441 children, a sample of 550 subjects was randomly selected. Numbers selected from each practice were proportionate to the total number of eligible participants per practice. Based on past written survey studies of these practices, we anticipated a 15–20% response rate to the initial mailed survey request, with up to 10% more respondents recruitable via internet and telephone follow-up, for a final target sample of 200 respondents. Assuming approximately 20% uptake of MyChart™ at the time of the survey,26 this allowed precision of estimates within ±5%, with 95% confidence.

Survey Development and Validation

The survey was developed with input from parents of children with ADHD, healthcare providers experienced in the care of children with ADHD, and lay individuals, followed by pilot testing with 21 predominantly low-income parents of children with ADHD. Questions about health service needs and interactions with providers were adapted from national surveys.27–29 Questions regarding attitudes, behaviors, and intentions about use of PHR were adapted from a previously published survey of adults regarding their own use of PHRs,30 and a survey of parents regarding their use of PHRs for their children.24 The survey was developed in English, and question stems targeted a 6th-grade reading level.

Data Collection and Management

The survey was administered in waves between October 1, 2013 and February 1, 2014. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted by the University of Rochester Clinical and Translational Science Institute.31 The survey questionnaire was self-administered via either paper-based or web-based tools by the parent/guardian of the referent child. For participants preferring a telephone interview, project staff conducted guided telephone interviews using the same questionnaire.

Measures

Survey variables were selected for comparison with prior studies and based on their conceptual relationship, according to the Technology Acceptance Model, with caregivers’ attitudes, intentions, and practices regarding use of personal health records for their children.32 Five categories of variables (see Appendix for details) were included: demographics/sample characteristics and attitudes regarding specific MyChart features; intentions regarding MyChart use; and interactions with healthcare providers. Information regarding the child’s age, gender, and primary care practice was obtained from eRecord.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.3 for Windows. Bivariate analyses explored the relationship between individual items and intent to use MyChart in the future. Pearson chi-square analyses or Fisher’s exact test (if cell size <5) were used for most comparisons. Variables with a p-value of <0.10 in bivariate analyses were included in a stepwise logistic regression analysis to build the most parsimonious model for factors related to respondents’ likelihood of using MyChart in the future. For multivariable analyses, parents were included only if they responded to a survey question about whether they planned to use MyChart in the future.

Results

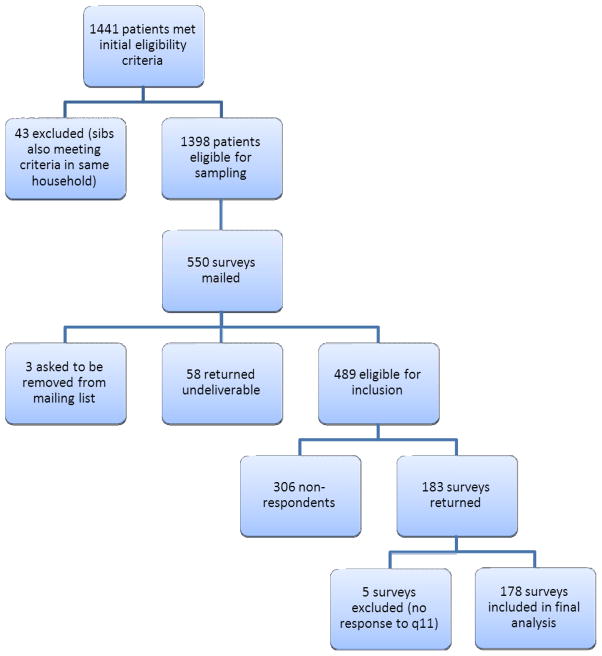

Sample and Response Rates (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Sampling and Eligibility

Of the initial eligible population of 1441 children who met inclusion criteria, 43 were excluded because a second child in the same household was eligible. We mailed 550 surveys, and received 183 completed questionnaires (response rate, 33%). Six respondents failed to answer the question about intent to use MyChart in the future, so a total of 177 respondents were included in the final multivariable analysis. We found no differences between responders and non-responders with respect to referent child age, child gender, socioeconomic area of residence (urban vs suburban) or primary care practice.

Demographics/Sample Characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of MyChart Users vs. Non-users and their Children

| overall (n=183) | MyChart Users (n=41) | MyChart Non- Users (n=142) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | p- valuea |

| relationship to child | |||||||

| parent | 167 | (96) | 39 | (95) | 128 | (96) | |

| grandparent | 7 | (44) | 1 | (2) | 6 | (4) | 0.58 |

| missing | 9 | 1 | 8 | ||||

| gender | |||||||

| male | 11 | (6) | 0 | (0) | 11 | (8) | |

| female | 163 | (95) | 40 | (100) | 123 | (92) | 0.06 |

| missing | 9 | 1 | 8 | ||||

| age (years) | |||||||

| mean (SD) | 34.8 | (8.1) | 33.5 | (6.9) | 35.2 | (8.5) | 0.25b |

| ethnicity | |||||||

| white | 46 | (26 | 14 | (35) | 32 | (23) | |

| black | 93 | (52) | 19 | (48) | 74 | (54) | |

| hispanic | 31 | (17) | 5 | (13) | 26 | (19) | |

| other | 8 | (5) | 2 | (5) | 6 | (4) | 0.46c |

| missing | 5 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| education | |||||||

| less than high school | 38 | (22) | 7 | (18) | 31 | (23) | |

| high school graduate | 65 | (37) | 14 | (35) | 51 | (37) | |

| some college or 2yr degree | 61 | (35) | 16 | (40) | 45 | (33) | |

| 4 yr college or more | 13 | (7) | 3 | (8) | 10 | (7) | 0.83 |

| missing | 6 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| Children | |||||||

| sex | |||||||

| male | 131 | (72) | 26 | (63) | 105 | (74) | |

| female | 51 | (28) | 15 | (37) | 36 | (26) | 0.20 |

| missing | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| age at survey | |||||||

| mean (SD) | 8.7 | (1.87) | 9.0 | (1.94) | 8.6 | (1.84) | 0.23b |

| age at diagnosis | |||||||

| mean (SD) | 5.8 | (2.11) | 6.0 | (2.21) | 5.7 | (2.09) | 0.47b |

| socioeconomic aread | |||||||

| inner city | 74 | (41) | 12 | (29) | 62 | (44) | |

| rest of city | 75 | (41) | 15 | (37) | 59 | (42) | |

| suburban | 33 | (18.) | 14 | (34) | 19 | (14) | 0.03 |

| missing | 1 | 0 | 2 | ||||

Pearson's Chi-Square except where otherwise noted.

Pooled t-test assuming equal variances where (Pr>F)>0.1.

Fisher’s exact test.

Socioeconomic area as defined by zip code of residence (see McConnochie et al 1997).

Three-quarters of referent children were male and most respondents were mothers of referent children. Respondents were 52% Black, 26% White, and 17% Hispanic. Most had completed at least a high school education (79%). The majority of the children used medications for their ADHD (72%) and received additional therapies (56%). At the time of the survey, 41 respondents (23%) had used MyChart for their child. MyChart users were more likely to reside in the suburbs (34%) than non-users (13%, p=0.03), but did not differ significantly from non-users with respect to respondent gender, age, race, education, or intentions to use MyChart in the future (p>0.05).

Access and Barriers to Use of MyChart

Among respondents who previously used MyChart for their child, 59% used it more than once. Respondents most often accessed the service from their home computer (50%) or smart phone (33%). They most frequently used it to review children’s immunization records (76%), view records for reasons other than immunizations (59%), and refill/view medications (37%). Among users, 40% strongly agreed that MyChart was easy to use; although 8% strongly disagreed, even these reported that they intend to continue using the service.

The 142 MyChart non-users most frequently reported as barriers to use lack of awareness about the service, or lack of computer or internet access (Table 2), but they rarely reported either discomfort sharing medical information on the internet or lack of computer literacy. Other barriers to MyChart use included password or access code problems, and lack of time.

Table 2.

“If you have not used MyChart for your child, what are the main reasons?”

| theme | details | number of commentsa | % responses | % respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| computer/internet access issues |

|

52 | 31 | 37 |

| lack of awareness |

|

51 | 30 | 36 |

| computer/application literacy |

|

22 | 13 | 16 |

| password/program access issues |

|

20 | 12 | 14 |

| lack of time |

|

18 | 11 | 13 |

| other | 2 | 1 | 1 |

total 168 responses from 141 caregivers who have not used MyChart for their child, caregivers could offer more than one reason.

Attitudes Regarding Specific MyChart Features

Table 3 shows that even non-users considered service features of MyChart potentially useful or very useful (mean score of 3.1 or higher). Overall, their responses were very similar to those of MyChart users, despite some statistically significant differences. Those intending to use MyChart in the near future were significantly more likely to perceive ADHD-relevant features to be useful or very useful in their child’s care (p<0.01).

Table 3.

Perceived Usefulness of Actual and Hypothetical MyChart Features

| All Respondents | MyChart Users | MyChart Non-Users | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 1-Not at all useful (%) | 2-not useful (%) | 3- useful (%) | 4-very useful (%) | mean scorea | count | mean scorea | count | mean scorea | p-valueb | |

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Usefulness for care of my child's ADHD: | |||||||||||

| A. Ability to request/schedule appointments | 170 | 9 | 6 | 25 | 60 | 3.4 | 40 | 3.4 | 130 | 3.3 | 0.64 |

| B. Ability to email my child's doctors | 168 | 11 | 12 | 21 | 56 | 3.2 | 39 | 3.5 | 129 | 3.1 | 0.09 |

| C. Ability to access information about ADHD | 169 | 11 | 9 | 27 | 53 | 3.2 | 40 | 3.4 | 129 | 3.2 | 0.20 |

| D. Ability to request medication refills | 172 | 8 | 7 | 23 | 62 | 3.4 | 40 | 3.3 | 132 | 3.4 | 0.62 |

| E. Ability to share information with my child's healthcare providers | 170 | 8 | 7 | 26 | 59 | 3.3 | 40 | 3.6 | 130 | 3.3 | 0.12 |

| F. Ability to track my child's symptoms | 171 | 10 | 17 | 26 | 47 | 3.1 | 40 | 3.1 | 131 | 3.1 | 0.86 |

| Summary Score: | 168 | 3.1 | 40 | 3.4 | 137 | 3.1 | 0.12 | ||||

| Usefulness for my child's care in general | |||||||||||

| A. Ability to track lab results over time | 168 | 8 | 11 | 25 | 57 | 3.3 | 40 | 3.4 | 128 | 3.3 | 0.59 |

| B. Ability to review immunizations | 166 | 5 | 7 | 22 | 66 | 3.5 | 40 | 3.8 | 126 | 3.4 | 0.02 |

| C. Ability to track doctor visits | 164 | 5 | 5 | 27 | 62 | 3.5 | 39 | 3.7 | 125 | 3.4 | 0.04 |

| D. Ability to have medical information available at any time | 168 | 7 | 4 | 21 | 69 | 3.5 | 40 | 3.7 | 128 | 3.5 | 0.16 |

| E. Ability to print my child's medication information | 168 | 7 | 5 | 20 | 67 | 3.5 | 40 | 3.7 | 128 | 3.4 | 0.07 |

| F. Reminders about check-ups, tests, etc. | 165 | 4 | 8 | 22 | 66 | 3.5 | 40 | 3.8 | 125 | 3.4 | 0.01 |

| Summary Score: | 158 | 3.5 | 39 | 3.7 | 119 | 3.4 | 0.06 | ||||

on Likert Scale 1–4 where 1=not at all useful, 2=not useful, 3=useful and 4=very useful.

Pearson’s Chi-Square comparing MyChart Users vs MyChart Nonusers.

Over 60% of caregivers (users and non-users) agreed to allow teacher input into records. While those reporting discomfort with sharing medical information over the internet favored this feature significantly less (p<0.01), 40% of those not comfortable would still permit teachers to provide information to providers via MyChart if the teacher could not view children’s records.

Interactions with Healthcare Providers

Responding to the question, “Who provides care for your child’s ADHD?”, respondents identified primary care providers (54%), behavior and development specialists (8%), or a mental health specialists (6%). Some children obtained care from two of these providers (10%), or all three (3%). Additionally, 18% of respondents identified other sources of care, including teachers (10%), counselors, and school therapists. About half of the children in the study (56%, n=98) received physical therapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy, and/or mental health counseling. Among respondents needing care coordination, 70% (n=70) could identify a person providing it.

In general, caregivers expressed satisfaction with providers, reporting that they: (1) always engaged families as partners in child’s care (60%), (2) always respected the families’ culture and values (56%), (3) always shared specific information needed by families regarding their child’s care (56%), and (4) always spent enough time with the child (38%). Overall, 59% of caregivers reported interactions that met our definition of family centered care (“always” or “usually” for all four components).

Multivariable Model

We generated a multivariable logistic regression model predicting caregiver intentions for future MyChart use. Caregivers who reported that they perceived MyChart tools to be useful or very useful in the management of their child’s ADHD had three-fold greater odds of planning to use MyChart in the future (OR=3.01, 95%CI:1.23,7.37). Likewise, caregivers who felt that their child’s provider engaged them as partners in their child’s care had 2.32 times higher odds of planning to use MyChart (95%CI: 1.20, 4.52). Caregiver race, SES, education, child’s service needs, and main provider type were not significantly associated with caregiver intentions regarding future MyChart use, and therefore were excluded from the model (Table 4).

Table 4.

Full multivariable logistic regression model (stepwise selection, alpha entry/exit=0.1)

| Adjusted Odds Ratio Estimate based on model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | df | estimate | standard error | Wald chi- square | p-value | point estimate | 95% Wald Confidence Limits |

| Family always engaged as partner in child's care | 1 | 0.84 | 0.34 | 6.18 | 0.013 | 2.32 | [1.20 , 4.52 ] |

| Perception of MyChart features as useful for management of ADHD | 1 | 1.10 | 0.46 | 5.85 | 0.016 | 3.01 | [1.23, 7.37] |

| Agree to allow school input into child's chart | 1 | 0.65 | 0.35 | 3.49 | 0.062 | 1.93 | [0.97 , 3.83] |

| Intercept | 1 | −1.58 | 0.50 | 9.77 | 0.002 | ||

Discussion

This study demonstrated that in urban, largely minority families with children who have ADHD, the strongest predictors of their intentions to use an electronic personal health record were 1) their perception of the usefulness of MyChart features in ADHD care management, and 2) how well children’s providers included them as partners in their children’s care. Most caregivers (82%) were favorably disposed to use MyChart, even though uptake of MyChart after one year of availability was still limited. In general, parents were most interested in using it for practical tasks like scheduling appointments and refilling prescriptions.

This study was conducted within the first year of MyChart implementation, a strategic point in its introduction to our patient population. Only 23% of caregivers reported using the tool at least once for their child. Because the survey was conducted in the early introduction phase, we could obtain information from new users and potential new users that may be highly relevant to other healthcare systems currently engaging in PHR implementation. Because of the HITECH Act of 2009 and new incentives for achieving “meaningful use” goals, many centers are striving to engage patients and families through PHRs. Therefore, our survey data is timely and applicable in many settings. These limitations are, however, significant: 10% of the initial sample was inaccessible (partly because they were not yet enrolled in MyChart), and the survey’s overall response rate was low (37%). Nonetheless, it is likely that problems encountered by users in finding and enrolling in MyChart apply to planned users of other PHR systems, and this information may help them to improve their implementation.

The most frequently-reported barrier was lack of awareness of MyChart’s availability, suggesting the need for better promotion of the service. In addition, participants reported program access problems, often never resolved because processes for resolution were unclear. These access problems may be linked to system security barriers. To improve performance of PHRs it will be critical to reconcile system security needs with caregiver needs.

We identified several opportunities to improve caregivers’ engagement with MyChart. One-third of current users viewed MyChart mainly on smart phones, and some non-users reported that they would use their smart phone if they had access. Hence, PHR use in the future would be enhanced by better advertising of the availability of mobile applications, and by optimization of key PHR tools for the mobile platform.

We found that a strong predictor of caregivers’ intentions to use MyChart was how well providers included caregivers in a partnership for their childrens’ care. Previous literature shows that user satisfaction with healthcare providers predicts engagement with PHRs, 32,35 so it is possible that providers’ partnering with caregivers and caregivers’ use of a PHR for shared care may be mutually supportive. The future challenge is to determine how best to employ these tools to engage caregivers who do not view themselves as true partners in their child’s care.

We found that 10% of caregivers identified teachers as their child’s main ADHD care provider, so it is unsurprising that many indicated they would permit teacher to have input into their child’s PHR. This finding highlights the importance of including teachers and other non-healthcare providers in interventions aimed to improve systems of care for children with ADHD.

A recent systematic review revealed that PHRs with active case management correlated with the best clinical outcomes.33 Since case management is particularly challenging for children with ADHD, this finding may provide an important clue for optimizing services they need. PHRs may serve this population best by combining high-tech approaches to flexible care management with high-touch care from family-preferred care coordinators, such as case managers in the medical home or school therapists.

Strengths and Limitations

This study had several limitations. As discussed above, the response rate was low (33%). Our survey results depended on self-reporting by caregivers, and thus may be subject to recall bias and social desirability bias. Language or literacy barriers may have contributed to nonresponse; our results are generalizable only to English-speaking caregivers at a minimum 6th-grade reading level. Additionally, by focusing on attitudes regarding MyChart, a response bias in favor of MyChart users may have occurred, inflating estimates of MyChart uptake and under-reporting of barriers to use. Because the study was cross-sectional, the data cannot be used to evaluate cause and effect, or to predict future uses of MyChart as it evolves.

By focusing only on perceptions and attitudes of parents, this survey addresses just one dimension of the multi-party dynamics that influence the ability of PHR-based tools to improve outcomes for children with ADHD. Future work needs to clarify provider perspectives, system capabilities, and the regulatory, privacy, organizational and environmental barriers that influence PHR usability and effectiveness.

Nevertheless, this study has a number of strengths warranting consideration. The survey addressed a random sample of a defined population of school-aged children with ADHD. Demographic characteristics of referent children resembled national estimates regarding the ADHD gender distribution (our sample is 72% male, equal to national estimates) and rates of medication use (~70%).1,34 Therefore, findings may generalize to other urban/semi-urban populations of school-aged children with ADHD.

Conclusions

Key findings from this study address the barriers and facilitators of PHR uptake by caregivers of children with ADHD in the first year of MyChart introduction. Lack of home computers or internet access, and lack of awareness about services were the most frequently reported barriers to MyChart use. Positive perceptions about MyChart’s practical utility and parent engagement as partners with healthcare teams most strongly correlated with future plans to use the service. Respondents’ enthusiasm for the potential value of PHRs supports the importance of integrating PHRs into care-coordination for children with ADHD. However, given that caregiver uptake was only 23%, it will take time to realize the full value of this technology.

Future Studies and Innovations

Future research should focus on practical implementation of PHRs as well as their impact on cost, efficiency, and quality of healthcare.35 We recommend streamlining security and access functions, adapting PHRs to mobile platforms, promoting bi-directional partnerships with caregivers as members of the healthcare team, and including non-medical providers such as teachers as PHR contributors. Such developments could optimize future electronic PHR tools for children with ADHD as well as for other chronic conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by funds provided by the University of Rochester Medical Center, Strong Children’s Research Center William L. Bradford Fellowship, in addition to funds provided by University of Rochester Pediatric Primary Care Training Program (NRSA) grant T32 HP12002-24-00 and University of Rochester Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NIH) grant UL1 RR024160.

The authors would like to thank the Center for Community Health, the Greater Rochester Practice Based Research Network, and the participating practices for their support of this project; and the parent pre-testers and pilot-testers who helped shape the content, format, and layout of the final questionnaire.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- EHR

electronic health records

- IT

information technology

- PCMH

patient centered medical home

- PHR

personal health records

- SEA

socioeconomic area

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease C and Prevention. Increasing prevalence of parent-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children --- United States, 2003 and 2007. MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2010 Nov 12;59(44):1439–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larson K, Russ SA, Kahn RS, Halfon N. Patterns of Comorbidity, Functioning, and Service Use for US Children With ADHD, 2007. Pediatrics. 2011 Mar 1;127(3):462–470. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ADHD. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011 Oct 16; doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danckaerts M, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Banaschewski T, et al. The quality of life of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. European child & adolescent psychiatry. 2010 Feb;19(2):83–105. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0046-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SS, Hinshaw SP. Predictors of adolescent functioning in girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): the role of childhood ADHD, conduct problems, and peer status. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology : the official journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53. 2006 Sep;35(3):356–368. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shilon Y, Pollak Y, Aran A, Shaked S, Gross-Tsur V. Accidental injuries are more common in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder compared with their non-affected siblings. Child: care, health and development. 2012 May;38(3):366–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu SY, Gau SS. Correlates for academic performance and school functioning among youths with and without persistent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Research in developmental disabilities. 2013 Jan;34(1):505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birnbaum HG, Kessler RC, Lowe SW, et al. Costs of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the US: excess costs of persons with ADHD and their family members in 2000. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005 Feb;21(2):195–206. doi: 10.1185/030079904X20303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cussen A, Sciberras E, Ukoumunne OC, Efron D. Relationship between symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and family functioning: a community-based study. European journal of pediatrics. 2012 Feb;171(2):271–280. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Ridder A, De Graeve D. Healthcare use, social burden and costs of children with and without ADHD in Flanders, Belgium. Clin Drug Investig. 2006;26(2):75–90. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200626020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galera C, Bouvard MP, Lagarde E, et al. Childhood attention problems and socioeconomic status in adulthood: 18-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 2012 Jul;201(1):20–25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.102491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodgkins P, Montejano L, Sasane R, Huse D. Cost of illness and comorbidities in adults diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a retrospective analysis. The primary care companion to CNS disorders. 2011;13(2) doi: 10.4088/PCC.10m01030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyers J, Classi P, Wietecha L, Candrilli S. Economic burden and comorbidities of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among pediatric patients hospitalized in the United States. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2010;4:31. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-4-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelham WE, Foster EM, Robb JA. The Economic Impact of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2007 Jul 1;32(6):711–727. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swensen AR, Birnbaum HG, Secnik K, Marynchenko M, Greenberg P, Claxton A. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: increased costs for patients and their families. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003 Dec;42(12):1415–1423. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guevara JP, Feudtner C, Romer D, et al. Fragmented care for inner-city minority children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2005 Oct;116(4):e512–517. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toomey SL, Chan E, Ratner JA, Schuster MA. The patient-centered medical home, practice patterns, and functional outcomes for children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Acad Pediatr. 2011 Nov;11(6):500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toomey SL, Finkelstein J, Kuhlthau K. Does connection to primary care matter for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Pediatrics. 2008 Aug;122(2):368–374. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knapp CA, Hinojosa M, Baron-Lee J, Fernandez-Baca D, Hinojosa R, Thompson L. Factors associated with a medical home among children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Matern Child Health J. 2012 Dec;16(9):1771–1778. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0922-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olson BG, Rosenbaum PF, Dosa NP, Roizen NJ. Improving guideline adherence for the diagnosis of ADHD in an ambulatory pediatric setting. Ambulatory pediatrics : the official journal of the Ambulatory Pediatric Association. 2005 May-Jun;5(3):138–142. doi: 10.1367/A04-047R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Co JPT, Johnson SA, Poon EG, et al. Electronic Health Record Decision Support and Quality of Care for Children With ADHD. Pediatrics. 2010 Aug 1;126(2):239–246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonander J, Gates S. Public health in an era of personal health records: opportunities for innovation and new partnerships. Journal of medical Internet research. 2010;12(3):e33. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Britto MT, Wimberg J. Pediatric personal health records: current trends and key challenges. Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123(Suppl 2):S97–99. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1755I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tom JO, Mangione-Smith R, Solomon C, Grossman DC. Integrated personal health record use: association with parent-reported care experiences. Pediatrics. 2012 Jul;130(1):e183–190. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weitzman ER, Kaci L, Mandl KD. Acceptability of a personally controlled health record in a community-based setting: implications for policy and design. Journal of medical Internet research. 2009;11(2):e14. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ancker JS, Barron Y, Rockoff ML, et al. Use of an electronic patient portal among disadvantaged populations. Journal of general internal medicine. 2011 Oct;26(10):1117–1123. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1749-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Survey of Children's Health. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/nsch.htm.

- 28.National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. 2009–2010 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/slaits/cshcn.htm.

- 29.Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Survey. http://cahps.ahrq.gov.

- 30.Agrawal R, Shah P, Zebracki K, Sanabria K, Kohrman C, Kohrman AF. Barriers to care for children and youth with special health care needs: perceptions of Illinois pediatricians. Clinical pediatrics. 2012 Jan;51(1):39–45. doi: 10.1177/0009922811417288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009 Apr;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis FD, Bagozzi RP, Warshaw PR. User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Management science. 1989;35(8):982–1003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finkelstein JKA, Marinopoulos S, et al. Enabling Patient-Centered Care Through Health Information Technology. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2012. No. 206 ed. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99854/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, et al. Trends in the Parent-Report of Health Care Provider-Diagnosed and Medicated Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: United States, 2003–2011. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(1):34–46. e32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaelber DC, Jha AK, Johnston D, Middleton B, Bates DW. A Research Agenda for Personal Health Records (PHRs) Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2008 Nov 1;15(6):729–736. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.