1. Introduction

Neuropathic pain is a manifestation of neuroplasticity [37], and its treatment remains a clinical challenge. Experimental manipulations of the spinal cord, brainstem, and thalamus to relieve pain are short-lived. The hippocampus, an area traditionally associated with learning, memory formation, and motivation, is now recognized as an integral region for chronic pain pathways. The hippocampus is dysfunctional during fibromyalgia [25], and evidence indicates a role for the hippocampus in pain memory [54, 82]. Hippocampal abnormalities during chronic pain include synaptic plasticity and reduced neurogenesis [49]. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) has been implicated in these abnormalities [49, 54].

While TNF increases locally following peripheral nerve injury [29, 50, 60–63, 81], we suggest that increased brain-TNF is responsible for centrally-mediated nociceptive hypersensitivity. We demonstrated that TNF increases in the brain of chronic constriction injury (CCI) rats [16, 33]. Drugs or gene manipulations that inhibit TNF decrease hyperalgesia. These include thalidomide, amitriptyline, anti-TNF antibody, and viral vector-introduction of the soluble TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) gene [28, 30, 33, 66, 67, 70]. Additionally, TNFR1- and TNFR2-knockout mice have reduced nociceptive hypersensitivity [80]. Interestingly, results of clinical trials using TNF blockers are conflicting. Reports include: patients with chronic sciatica did not benefit from infliximab (TNF antibody) [43, 44]; patients with discogenic low back pain did not experience relief when etanercept (sTNFR2-IgG, blocks TNF actions) was administered into the pain-generating disc [14]. However, patients with chronic back pain did experience relief following treatment with epidural etanercept [13] and perispinal etanercept [77]. Moreover, several drugs (i.e., amitriptyline, thalidomide) that alleviate pain-related behaviors have been shown to decrease TNF in the brain, and systemically [33, 68, 70, 88].

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) can be used to block specific gene expression in the brain, but its effectiveness is short-lived (1–3 days) and large quantities are necessary [21, 26, 73, 75, 76]. Therefore, use of siRNA therapeutically requires an appropriate vector for delivery. Nanoparticles are ideal non-viral tissue delivery vectors for polynucleotides [4, 11, 38, 41]. They are sustained within the cell and escape the degradative endo-lysosomal compartment. Gold nanoparticles and nanorods (GNRs) have been applied in vivo because of their low/minimal toxicity in biological environments [15, 32, 57, 86]. Previously we demonstrated that siRNA complexed to GNRs and injected into the rat hippocampus effectively silenced targeted gene expression [6].

In this study, we hypothesized that an increase in TNF production in the hippocampus is necessary for expression of hyperalgesia and allodynia. To test this, we predicted that prolonged reduction of hippocampal TNF would effectively ablate these nociceptive behaviors in a rat CCI model, with limited or no side effects. The inert GNRs with engineered surface properties acted as nanocarriers, providing for siRNA stability and controlled release at the target site. A single hippocampus nanoplex injection silenced CCI-induced TNF, and resulted in alleviation of nociceptive behavior. These results support our hypothesis that targeting TNF in the brain offers a novel therapeutic strategy for treating chronic, neuropathic pain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Male, Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Sprague – Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) weighing 200–250 g were used in all experiments. The rats were initially housed in groups of 2–3 per cage at 23 ± 1°C in an accredited, laboratory animal facility with access to food and water, ad libitum. Following stereotaxic surgery, rats were housed individually for the duration of the experimental protocol. The animals were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle with the lights on from 06:00 to 18:00. Rats were given at least 3 days to acclimate to the animal facilities before baseline testing occurred. All procedures were approved by the University at Buffalo’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with the guidelines for the ethical treatment of animals established by the National Institutes of Health and the Committee for Research and Ethical Issues of IASP [90]. Every effort was made to use the minimum number of rats possible to minimize pain and suffering to the animals, but still maintain appropriate statistical power for the study.

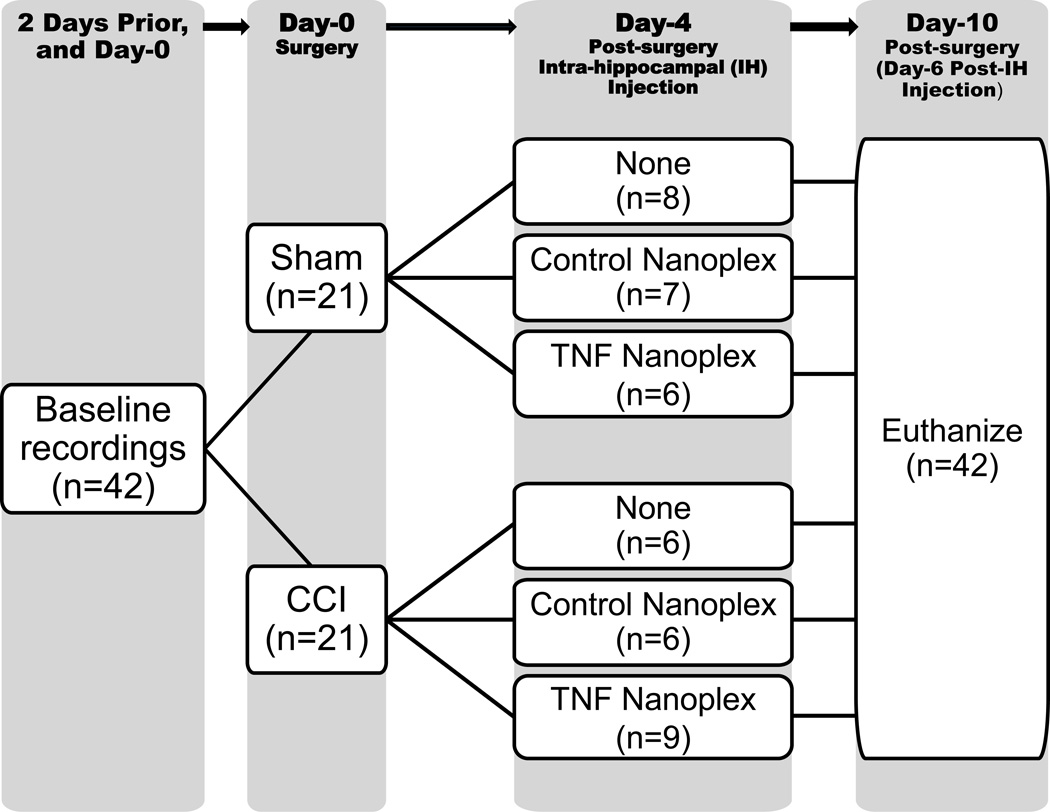

2.2. Experimental model

The experimental paradigm implemented for this study is illustrated in Figure 1. A total of 42 rats was used for this project, corresponding to n=21 for all sham animals and n=21 for all CCI rats. However, the treatment subgroups varied in respective n numbers; this was due to the redistribution of three rats in the study design as follows: 1 extra sham-operated rat remained in the sham group because it did not reach the appropriate weight (≥ 250 grams) needed to accurately perform stereotaxic injection for inclusion in the sham+control nanoplex group. In order for experimental animals to be run in parallel with controls, two of the rats that were initially designated to receive CCI surgery (1 from the CCI group and 1 from the CCI+control nanoplex group, prior to receiving the treatment) were redistributed to the CCI+TNF nanoplex group, as initial staining procedures used all the tissue from the first two sets of CCI+TNF nanoplex rats, and additional tissue was needed for completion and statistical analysis of the staining experiments.

Figure 1. Timeline schematic of experimental paradigm.

Rats were weighed prior to, and on the day of CCI/sham surgery, and every other day thereafter before nociceptive behavioral measurements were taken. Weight was matched before CCI/sham surgery, and rats in all groups gained an equivalent amount of weight during the course of the study. Rats microinjected with the TNF nanoplexes into the CA1 region of the contralateral hippocampus did not experience any difference in weight gain over time (6 days) as compared to the paired control animals (data not shown). No motor dysfunction was observed in rats receiving microinjection into the hippocampus. Therefore, weight gain/loss was not affected by either type of surgery or stereotaxic injection, and all rats exhibited similar grooming behaviors throughout the study.

2.3. Chronic constriction injury (CCI)

Loose ligatures were applied around the common sciatic nerve of the right hind paw according to described methods [2]. Briefly, rats were anesthetized with Ketamine (75 mg/kg) and Xylazine (10 mg/kg), i.p., prior to aseptic surgery. The sciatic nerve was exposed unilaterally at the level of the trifurcation into the sural, tibial, and common peroneal nerves. Four ligatures (4.0 chromic gut, Harvard Apparatus Inc., Holliston, MA) were placed loosely around the nerve, ~ 1 mm apart, proximal to the trifurcation. Ligatures were tied such that constriction to the diameter of the nerve was barely discernable, allowing for uninterrupted circulation through the epineural vasculature and innervation to the lower limb. In sham procedures, the nerve was similarly exposed and freed of adherent tissue/muscle, but no ligatures were placed. The incisions were closed with surgical clips. All surgeries were performed between 09:00–12:00.

2.4. Synthesis of gold nanorod/siRNA complex

GNRs were prepared by the seed-mediated growth method in cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) surfactant solution, as described [19, 87]. CTAB forms rod-like micelles above its critical micelle concentration, forming the template for GNR synthesis. Positively charged CTAB-coated GNRs were further prepared for siRNA loading by adding two successive layers of polyelectrolytes, (a) negatively charged PEDT/PSS (poly(3,4ethenedioxythiophene)/-poly(styrenesulfate)), 20%, and (b) positively charged PDDAC (poly(diallyldimethyl ammonium chloride)), 20% (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA). This polymeric multilayering was necessary to generate positively charged GNRs that “mask” the cytotoxic CTAB layer. The cationic GNRs were then complexed electrostatically with the anionic siRNA in PBS solution for ≥ 30 min at room temperature. The binding efficiency of siRNA with GNRs was confirmed using agarose gel electrophoresis, as described previously [6, 7, 11]. Using this method, the most efficient siRNA loading of GNRs was determined to be 0.2 nmole siRNA/4 µl of GNR. Surface charge (zeta potential) and size measurements were performed at 25°C using a 90-Plus dynamic laser scattering (DLS) analyzer (Brookhaven Instrument Corp.); the surface charge of free GNRs was +28.6mV, and the GNR complexed with siRNA was −2.4mV; the hydrodynamic sizes were 110±10 nm at room temperature. The aspect ratio (length:width) of the GNRs was 2.2–2.5, as measured by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The polydispersity index (PDI) was less than 0.3 indicating the narrow size distribution of the GNR complex in aqueous solution. The effective hydrodynamic radius of the nanoplex was approximately 45 nm. The nanoplexes were prepared fresh before each experiment.

2.5. Intra-hippocampal injection

On the fourth day post CCI/sham surgery, rats were administered either control nanoplexes (GNR-scrambled siRNACy3;0.2 nmol/4 µl; Silencer®Cy™3-Labeled Negative Control #1 siRNA, Ambion, Austin, TX) or TNF nanoplexes (GNR-TNF siRNACy3; 0.2 nmol/4 µl; Silencer®Cy™3-Labeled Select TNF-targeting siRNA) stereotaxically into the contralateral (left) hippocampal CA1 region. Briefly, rats were anesthetized with Ketamine (75 mg/kg) and Xylazine (10 mg/kg) i.p. and secured on a stereotaxic platform. Coordinates: A-P, −3.3 mm relative to bregma; lateral, 1.6 mm relative to the midline (saggital crest); depth, −2.8 mm from dura were used for injection into the CA1 region of the hippocampus [52].The concentration of nanoplexes (0.2 nmol in 4 µl) for injection was based on both in vitro and in vivo studies. Each injection was at a rate of 0.5 µl/min, using a 30 G stainless steel needle on a 10 µl Hamilton syringe held by the micromanipulator on the stereotaxic apparatus [6, 41, 46]. The needle remained in place for another 3 minutes after each injection to allow for sufficient diffusion. Incisions were closed with surgical staples, and rats were observed daily for any adverse reactions. Authentication of the injection site was established by gross morphology of the hippocampus at dissection.

2.6. Thermal hyperalgesia measurements

At specified times post-CCI, the thermal nociceptive threshold was measured in each hind paw. Thermal hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to noxious sensory stimuli) was measured by determining changes in paw withdrawal latency (PWL) using a plantar algesia apparatus (model #33, Analgesia Meter, IITC Life Science Instruments, Woodland Hills, CA) [31]. A “difference score” generated from subtracting the contralateral PWL from the ipsilateral PWL was used as an index of hyperalgesia. PWL was measured using an intense heat source to stimulate thermal receptors in the sole of the foot. A maximal automatic cut-off latency of 15 seconds was used to prevent tissue damage. Rats were placed in Plexiglas chambers, on top of a temperature maintained (32 ±0.1 °C) glass surface. Rats were acclimated to the testing apparatus for 7–10 min (or until exploratory behavior ceased), and measurements of the thermal withdrawal threshold were taken for each hind paw. Baseline latencies were determined before experimental treatment for all animals as the mean of three separate trials, taken 3, 2, or 1 day pre-surgery and/or the day of the surgery (prior to surgery, day 0). Paw withdrawal responses were measured every other day alternating one day post-surgery for a 10 day period. Only rapid hind paw movements away from the thermal stimulus (with or without licking of hind paw) were considered to be a withdrawal response. Paw movements associated with weight shifting or locomotion were not counted. Each hind paw was measured three times at ≥4 minute intervals, and the averaged values for each day were used to compute thermal hyperalgesia (ipsilateral PWL– contralateral PWL). All measurements were recorded between 07:00 and 12:00.

2.7. Mechanical allodynia measurements

Calibrated Semmes-Weinstein (von Frey) monofilaments (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL) were used to measure the hind paw withdrawal threshold (in grams force) in rats [27, 64, 74, 84, 89]. Rats were placed in a wire-mesh raised cage and were acclimated for 7–10 min (or until exploratory behavior ceased). Calibrated filaments were applied to the plantar surface of the hind paws, and paw withdrawal reflexes were recorded for each hind paw. The criterion response was reflexive withdrawal without stepping. The series of von Frey monofilaments (bending forces in mN, gram forces): 4.08(1), 4.17(1.4), 4.31(2), 4.56(4), 4.74(6), 4.93(8), 5.07(10), 5.18(15), 5.46(26), 5.88(60), 6.10(100), 6.45(180), 6.65(300)) were applied perpendicular to the central region of the plantar surface in ascending order; filaments were depressed until they bent. Each hind paw was measured two times with brief probe application at ≥ 1 min intervals. If withdrawal did not occur, the next larger filament was applied. When the hind paw was withdrawn from a filament, the value of that filament (grams) was the withdrawal threshold. Regular movement and inadvertent movements were not considered as a direct response to the filament application. The differential response between the baseline and post-surgery values for each hind paw was a measure of mechanical allodynia. The individual paw withdrawal threshold was determined by 3 days of baseline testing performed between 07:00 and 12:00; these baseline values were averaged to provide one value. Paw withdrawal responses were measured every other day alternating one day post-surgery for a 10 day period. These measurements were carried out by the same male researcher for consistency.

2.8. Caliper measurements of sciatic nerve diameter

Sciatic nerve diameter measurements were performed to assess the degree of tissue edema, an indirect measure of inflammation. Following decapitation, the sciatic nerves from both legs were excised, placed on ice, and the diameters of the sciatic nerves were measured using a digital caliper (VWR International, West Chester, PA). The ipsilateral sciatic nerves were harvested by cutting the nerves shortly above the location of the ligatures and ~1.0 cm distally. Sciatic nerves from the contralateral side, as well as from sham-operated animals were removed in a similar manner. Three measurements each were recorded for the proximal, ligatured, and distal sections of the ipsilateral nerves, and averaged to give one value for nerve diameter. Similar measurements were made for the contralateral nerves. The results are expressed as a “difference value” generated by subtracting the average diameter of the contralateral nerve (mm) from the average diameter of the ipsilateral nerve (mm).

2.9. TNF bioassay

The lytic effect of TNF on WEHI-13VAR fibroblast cells was used to analyze brain tissue homogenates and blood serum samples for the presence of biologically active TNF [36, 39]. Immediately after sacrifice, trunk blood was collected into a sterile tube, incubated on ice for 15–30 min, and centrifuged at 1,500 × g (10 min at 4°C) to separate the serum from the clot. The serum was collected and stored at −30°C. Tissue samples (right and left hippocampi, locus coeruleus, sciatic nerves, and parietal cortex as a control region) were harvested on ice, snap frozen, and stored at −30°C until processed. Samples were weighed and homogenized in 3ml RPMI-1640 supplemented with glutamine (2 mM). Supernatants from homogenates centrifuged at 14,000 × g (15 min at 4°C) were stored at −30°C. Briefly, WEHI-13VAR fibroblast cells, a TNF-sensitive cell line derived from a mouse fibrosarcoma (ATCC, Manassas, VA), were grown in culture medium containing: RPMI-1640, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Chicago, IL), and 3 µg/ml gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical, St. Louis, MO) in T75 flasks at 37°C, 95% RH, 5% CO2. Cells used in the TNF bioassay were cultured to approximately 90% confluency and were always below passage 25 to avoid loss of TNF sensitivity. Cells were prepared for the assay by detaching with 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical, St. Louis, MO), adding 10 ml/flask culture medium, centrifuging at 800 × g for 5 min at RT, and resuspending in culture medium supplemented with 1 µg/ml actinomycin D (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) to a concentration of 500,000 cells/ml. One hundred microliters of cell suspension was added to each well of a flat-bottom 96-well tissue culture plate containing 100 µl of 2-fold serial dilutions of unknown samples, in triplicate, or known concentrations of recombinant rat TNF standards (rrTNF, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in diluting medium, RPMI-1640, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, and 15 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical, St. Louis, MO). Following 20 hr of incubation at 37°C, 95% RH, 5% CO2, 10 µl of Cell Proliferation Reagent WST-1 (a solution of the tetrazolium salt, WST-1 (4-[3-(4-iodophenyl)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-5-tetrazolio]-1,3-benzene disulfonate and the electron coupling reagent, mPMS (1-methoxy-5-methyl-phenazinium methyl sulfate), Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) in diluting medium was added to each well. After incubating for 4 hr at 37°C, 95% RH, 5% CO2, the absorbance at 440 and 700 nm was measured using a SpectraMax 190 microplate reader with SoftMax Pro v.4.0 acquisition and analysis software (MDS Analytical Technologies, Sunnyvale, CA). A standard curve (0.01 pg/ml – 10,000 pg/ml, reverse sigmoid in shape) of the (OD440-OD700) vs log[TNF] was plotted and the [TNF] of each sample was determined from the dilution closest to the inflection point of the standard curve. This assay has a detection limit of approximately 1 pg/ml [39]. WST-1 counting solution was used as a cell viability indicator, which is quantitated spectrophotometrically [3]. Increasing TNF concentration results in augmented cell death and, therefore, a reduced absorbance at 440 nm. Results are expressed as pg/100 mg tissue weight for the brain tissue samples and pg/ml for the blood serum samples.

2.10. Immunohistochemistry for TNF

Hippocampi and sciatic nerve samples harvested immediately after decapitation were snap frozen (by means of liquid nitrogen) in Tissue-Tek® O.C.T. (optimal cutting temperature) compound, serially cut using a cryostat into 6–8 µm sections, placed on StarFrost™ glass slides (Mercedes Medical, Sarasota, FL), and stored at −30°C until stained. Slides were brought to room temperature for ~ 30 minutes and sections were fixed in acetone at room temperature for 15 minutes. Sections were circumscribed with an ImmEdge pen (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) and allowed to dry at room temperature by fan for 10 minutes or over-night by air. Immediately prior to staining, samples were rehydrated in 1X PBS for 10 minutes. To block endogenous peroxidase, samples were incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature in 0.3% H2O2 then rinsed with 1X PBS. To block non-specific staining, slides were incubated for 30 minutes in 20% goat serum. Goat serum was removed without rinsing (by blotting), and the primary antibody rabbit anti-mouse/rat TNFα (Calbiochem) was added to the sections at a 1:200 dilution. A 1:200 dilution of a stock solution (same initial protein concentration) of normal rabbit serum (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the negative control. Slides were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour, rinsed 2 times with PBS for 5 minutes each, and incubated protected from light for 30 minutes with the secondary antibody, biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (VectaStain kit, Vector Labs) that had been preabsorbed (1:100 dilution) in normal rat serum at 37°C for 45 minutes prior to use. After rinsing with PBS, slides were incubated with ABC solution (avidin-biotinylated peroxidase H enzyme conjugate, VectaStain Kit) for 30 minutes and again rinsed with PBS. 3,3’-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution (SIGMA FAST™ DAB tablets dissolved in 0.05 M Tris buffer supplemented with 0.01 M imidazole for color enhancement) was added to the tissue sections for 5 minutes in the dark, and the slides were rinsed with house distilled H2O (2 rinses, 5 minutes each). Slides were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin, dehydrated by graded ethanol solutions (70, 90, 90, 100, 100%), cleared of residual ImmEdge pen marking with 2 xylene rinses, and coverglass was mounted with Cytoseal™ 60 (Richard-Allan Scientific, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI).

Slide images were taken using a ScanScope (Aperio) Slide Scanner (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL), and snapshots of tissue sections were captured at either 200× (sciatic nerve) or 400× (hippocampus) magnification and saved as tiff files. ImageJ 1.32j software (NIH, USA, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) with the Color Deconvolution plug-in to perform stain separation was used for subsequent image analysis, as described [46, 70]. Following background subtraction, color deconvolution of the RGB tiff files was performed using the built-in hematoxylin and DAB (H DAB) vector, and the third (complementary) 8-bit image generated was white [58]. The second 8-bit tiff file corresponding to the DAB (TNF) contribution was then further analyzed. This 8-bit tiff file was converted to grey-scale and thresholded in ImageJ using the auto threshold tool. Resultant mean density values for TNF staining were compared.

2.11. Immunofluorescence staining

Hippocampal sections stored at −30°C in the dark were brought to room temperature and fixed in acetone for 10 min at room temperature. Slides were completely dried prior to hydration with 3 rinses of PBS, 5 min each, at room temperature. Immunofluorescence staining procedures were followed as previously published [6, 46]. Briefly, non-specific immunoglobulin binding was blocked with 10% goat serum for 20 min at room temperature. Slides were blotted without washing to remove serum. Sections were incubated with primary antibody for either glial fibrillary acidic protein, mouse monoclonal anti-GFAP (1:30,000, Sigma-Aldrich) or neurofilament-200, mouse monoclonal NF-200 (1:30,000, Sigma-Aldrich), both of which cross-react with rat, for 120 min in PBS/1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (fraction V)/10% goat serum at room temperature in a humidified chamber in the dark. Slides were washed 3 times, 5 min each, in PBS. Sections were incubated with the secondary antibody, goat anti-mouse IgG1-AlexaFluor 647 (1:2,000, Invitrogen), in PBS/1% BSA for 120 min at room temperature in a humidified chamber in the dark. Slides were washed 5 times, 5 min each, in PBS. Sections were incubated with Hoechst nuclear stain (10 µM) for 1 min. Slides were rinsed with PBS for 5 min. Coverglass was mounted on the sections using Fluoromount™ aqueous mounting medium with anti-fade properties (Sigma) and the edges sealed with Cytoseal™-60 (Thermo Scientific). Slides were stored in the dark at 4°C until analyzed. Fluorescence images were obtained with a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 fluorescence microscopy system with 20X objective (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY). Representative photomicrographs were acquired using an AxioCam MrM cooled CCD camera and AxioVision v.4.8 image acquisition software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY) with constant illumination and exposure settings.

2.12. PCR

Left hippocampi were individually placed into 1 ml RNAlater solution (Ambion) and stored at −30°C until RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted by an acid guanidinium-thiocynate-phenol-chloroform method, as described using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen-Life Technologies) [12]. Brain tissue samples were processed as published [6, 7]. Real-time qRT-PCR was used to determine the relative abundance of each mRNA species by using specific primers and the Brilliant SYBR green Q-PCR master mix from Strategene. The specific primers used for rat TNF-α were as follows: Forward primer: 5’-TACTGAACTTCGGGGTGATTGGTCC-3’ and reverse primer: 5’-CAGCCTTGTCCCTTGAAGAGAACC-3’, determined from GenBank under accession number X66539. Extracted samples were analyzed as published [6, 7, 46]. RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the reverse transcriptase kit from Promega. All data were controlled for quantity of RNA input by performing measurements on an endogenous reference gene, β-actin (GenBank Accession number X00351). As previously published [6, 7, 46], the relative expression of mRNA species was calculated using the comparative CT method [9, 53].

2.13. Statistics

Results are expressed as mean values ± S.E.M. Analysis of data was performed using SigmaStat/SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Data were analyzed using Student’s t-test, paired t-test, Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test, one-way or two-way ANOVA, or Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA on Ranks, as indicated in the figure legends. For allodynia behavioral data, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), or mixed-effects model, for repeated measures was used to analyze change from baseline scores as a function of surgery, treatment, time post-treatment, and their interaction. To account for differences in allodynia baseline values between groups, the baseline scores were considered as covariates in the model. When differences were observed, appropriate post hoc t-tests were performed as indicated in the figure legends. A difference was accepted as significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of CCI on bioactive TNF protein levels

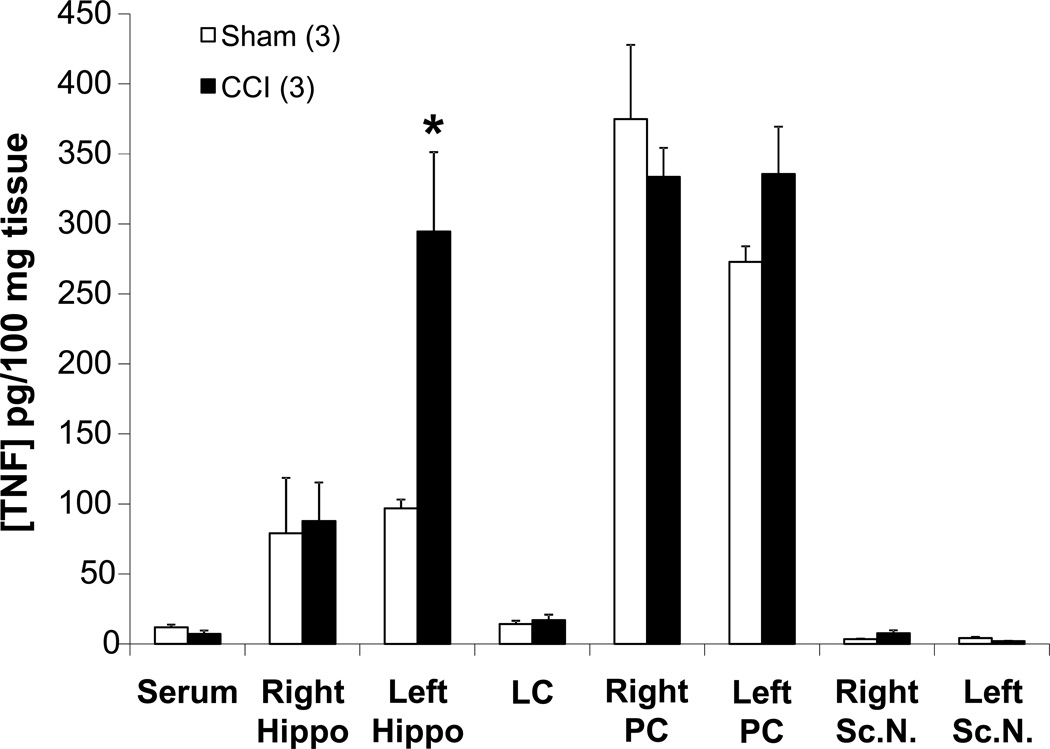

CCI of the sciatic nerve locally increases bioactive TNF protein levels in the ipsilateral sciatic nerve when compared to sham-operated animals [17]. TNF levels in the ligatured sciatic nerves of the CCI rats trended toward being increased compared to sham-operated rats (7.5 ± 2.3 pg/100 mg tissue vs 3.5 ± 0.2 pg/100 mg tissue, respectively, p < 0.1, Student’s t-test; Fig. 2) at day-10 post-CCI. Interestingly, TNF levels in the CCI rats were increased 3-fold in the contralateral (left) hippocampus (294.5 ± 56.7 pg/100 mg tissue) compared to hippocampi from sham-operated animals (96.9 ± 6.2 pg/100 mg tissue) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced bioactive levels of TNF.

Comparison of bioactive TNF levels between untreated sham and CCI rats euthanized on day 10 post-surgery. Statistical significance indicated (* p < 0.05) was by Student’s t-test. CCI = chronic constriction injury; Rt. Hippo = right hippocampus; LC = locus coeruleus; PC = parietal cortex; Sc.N. = sciatic nerve; PC was assayed as a control region to test for diffusion effects. The n for the group is indicated in parentheses

3.2. Contralateral hippocampus TNF nanoplex injection alleviates thermal hyperalgesia

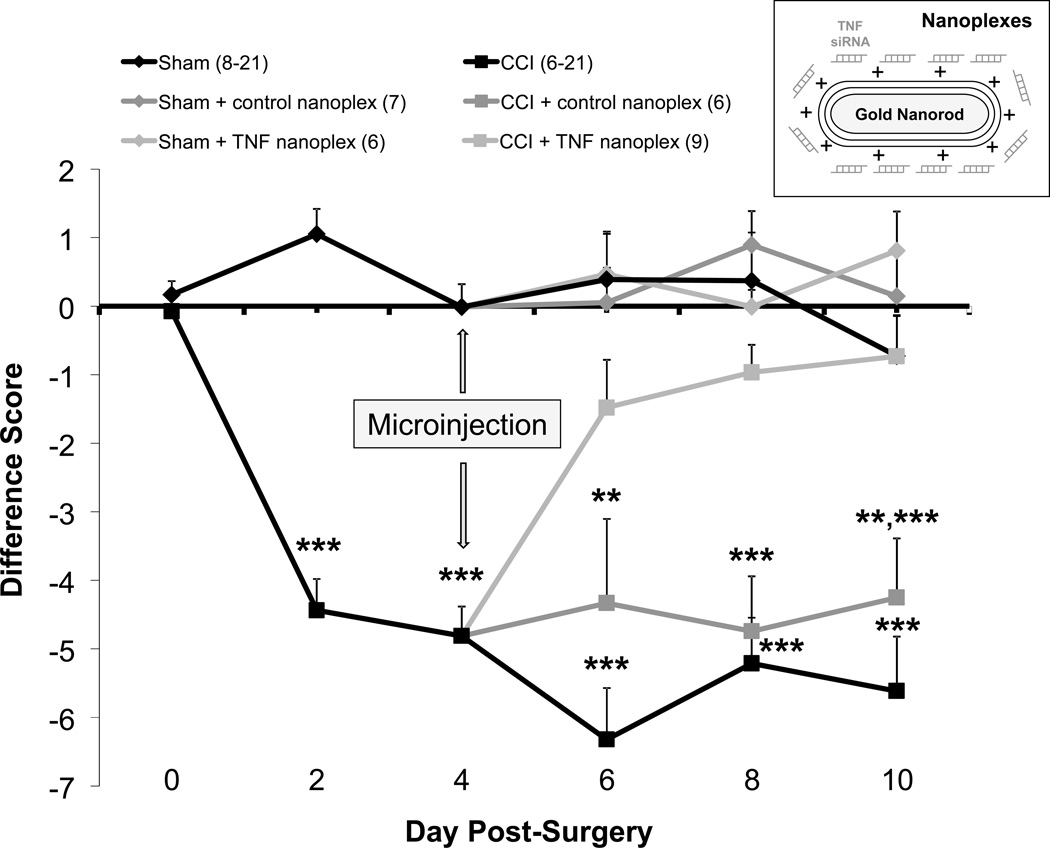

Thermal hyperalgesia, as assessed by withdrawal latency of the ipsilateral (right) hind paw, was detected 2 days post-ligature placement and continued through day 10 in rats that did not receive a hippocampal injection and those that had control nanoplexes injected into the contralateral hippocampus (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Findings (Table 1) show no difference in the actual response of the contralateral hind paws as assessed at day-2 through day-10 post-CCI, indicating the lack of a contralateral hind paw effect due to unilateral nerve injury. TNF nanoplexes injected into the contralateral CA1 hippocampal region on day 4 post-CCI reduced hypersensitivity to a noxious thermal stimulus by day 6 post-CCI such that the values were not different from sham operated animals, but were different from CCI rats and CCI rats receiving a control nanoplex microinjection. The absence of thermal hyperalgesia in the TNF nanoplex-injected CCI rats remained throughout the time frame assessed (10 days post-CCI surgery) (Fig. 3 and Table 1).

Figure 3. Chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced thermal hyperalgesia and the effect of a single injection of nanoplexes into the contralateral CA1 hippocampal region.

Thermal hyperalgesia is expressed as the difference (ipsilateral – contralateral) score for hind paw withdrawal latency (in seconds) to a noxious thermal stimulus. Baseline latencies were determined before experimental treatment for all animals as the mean of three separate trials, taken one and two days pre-surgery and on the day of surgery (day 0). Each point is expressed as the mean ± SEM (number of rats in parentheses). Rats received either CCI or sham surgery (day 0) on the right hind leg. On day-4 post-surgery, sham-operated and CCI rats were microinjected with either GNR-scrambled siRNACy3 (control nanoplex) or GNR-TNF siRNACy3 (TNF nanoplex) into the contralateral CA1 hippocampal region (inset). Rats were euthanized on day-10 post-surgery (day-6 post-microinjection). Statistical significance was determined with ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison test: CCI rats differ from sham-operated rats at days-2 and −4 post-surgery, *** p < 0.001. Following nociceptive behavior testing on day-4 post-CCI/sham surgery, rats were subdivided into one of six groups for contralateral intra-hippocampal (CA1 region) microinjection: Sham (no injection), sham receiving control nanoplex, sham receiving TNF nanoplex, CCI (no injection), CCI receiving control nanoplex, and CCI receiving TNF nanoplex. CCI rats at day-6 differ, *** p < 0.001 as compared to all sham groups and to the CCI + TNF nanoplex group; CCI + control nanoplex rats at day-6 differ, ** p < 0.01, compared to all sham groups. CCI and CCI + control nanoplex rat groups at day-8 differ, *** p < 0.001 as compared to all sham groups and to the CCI + TNF nanoplex group. CCI rats at day-10 differ, *** p < 0.001 as compared to all sham groups and to the CCI + TNF nanoplex group; CCI + control nanoplex rats at day-10 differ, *** p ≤ 0.001 as compared to sham + TNF nanoplex and sham + control nanoplex groups, ** p = 0.01 as compared to sham rats and the CCI + TNF nanoplex rat group. CCI = chronic constriction injury. The n for the group is indicated in parentheses.

Table 1.

Withdrawal latencies (in seconds) for the ipsilateral and contralateral hind paws of sham-operated and CCI rats groups, expressed as the average (mean ± S.E.M.) of the number of animals in brackets.

| Day Post-Surgery | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

| CCI-ipsilateral [6] | 11.4 ± 0.7$ | 7.3 ± 1.4 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | 7.5 ± 0.8 | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 7.2 ± 0.8 |

| Sham-ipsilateral [8] | 9.9 ± 0.9 | 11.2 ± 0.9* | 12.9 ± 0.9** | 11.7 ± 0.7*** | 12.0 ± 0.8*** | 11.7 ± 0.8*** |

| CCI + control nanoplex-ipsilateral [6] | 14.4 ± 0.2**,$ | 7.9 ± 1.1 | 10.1 ± 0.9 | 8.2 ± 0.7 | 8.4 ± 0.5 | 9.5 ± 0.8 |

| CCI + TNF nanoplex-ipsilateral [9] | 13.6 ± 0.3ψ | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 7.7 ± 0.4 | 8.8 ± 0.8† | 10.4 ± 0.5*,ӿ,++ | 9.7 ± 0.6#,ӿ,‡ |

| Sham + control nanoplex-ipsilateral [7] | 13.5 ± 0.6 | 13.9 ± 0.7*** | 13.1 ± 0.9** | 13.4 ± 0.6*** | 14.1 ± 0.4*** | 13.4 ± 0.6*** |

| Sham + TNF nanoplex-ipsilateral [6] | 13.0 ± 0.5 | 13.2 ± 0.7*** | 12.0 ± 1.4* | 11.7 ± 1.2** | 11.7 ± 1.4** | 12.5 ± 0.7*** |

| CCI-contralateral [6] | 12.3 ± 0.5 | 10.1 ± 1.4+ | 13.8 ± 0.4 | 13.8 ± 0.7 | 12.6 ± 0.5 | 12.8 ± 1.0 |

| Sham-contralateral [8] | 10.0 ± 0.9* | 10.4 ± 1.2 | 12.1 ± 0.5 | 11.3 ± 0.5 | 11.6 ± 0.6 | 12.4 ± 0.9 |

| CCI + control nanoplex-contralateral [6] | 14.4 ± 0.2 | 13.4 ± 0.5 | 14.1 ± 0.3 | 12.6 ± 1.2 | 13.1 ± 1.1 | 13.8 ± 0.8 |

| CCI + TNF nanoplex-contralateral [9] | 13.1 ± 0.3@ | 11.5 ± 0.7 | 12.4 ± 0.6 | 10.5 ± 0.9* | 11.3 ± 0.6 | 10.4 ± 0.9 |

| Sham + control nanoplex-contralateral [7] | 13.1 ± 0.6 | 13.2 ± 0.7 | 13.4 ± 1.0 | 13.3 ± 0.6 | 13.2 ± 0.4 | 13.3 ± 0.8 |

| Sham + TNF nanoplex-contralateral [6] | 12.8 ± 0.7 | 11.4 ± 0.5 | 12.8 ± 1.2 | 11.2 ± 0.9 | 11.7 ± 1.2 | 11.6 ± 0.5 |

Baseline withdrawal latency values for all animals (combined from all groups) before CCI/Sham surgery was 12.6 ± 0.3 sec for ipsilateral and 12.5 ± 0.3 sec for contralateral hind paws (n=42). Statistical analysis for comparison of animal groups at each day (down columns): Upper portion of Table, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni with comparison to CCI-ipsilateral,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001,

p = 0.075. Lower portion of Table, ANOVA followed by Bonferroni with comparison to CCI-contralateral,

p < 0.05. Statistical significance for thermal hypersensitivity behavior within each animal group (across rows) determined using Repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison post-hoc test:

p < 0.001 for days 2, 6, 8, and 10 post-CCI, p < 0.01 for day 4 post-CCI,

p < 0.01 for days 4 and 6 post-CCI;

p < 0.001 for all days (2–10) post-CCI,

p < 0.001 for day 2 post-CCI,

p < 0.01 for day 4 post-CCI,

p < 0.05 for day 2 post-CCI,

p = 0.074 for day 4 post-CCI;

p < 0.01 for days 6 and 10 post-CCI.

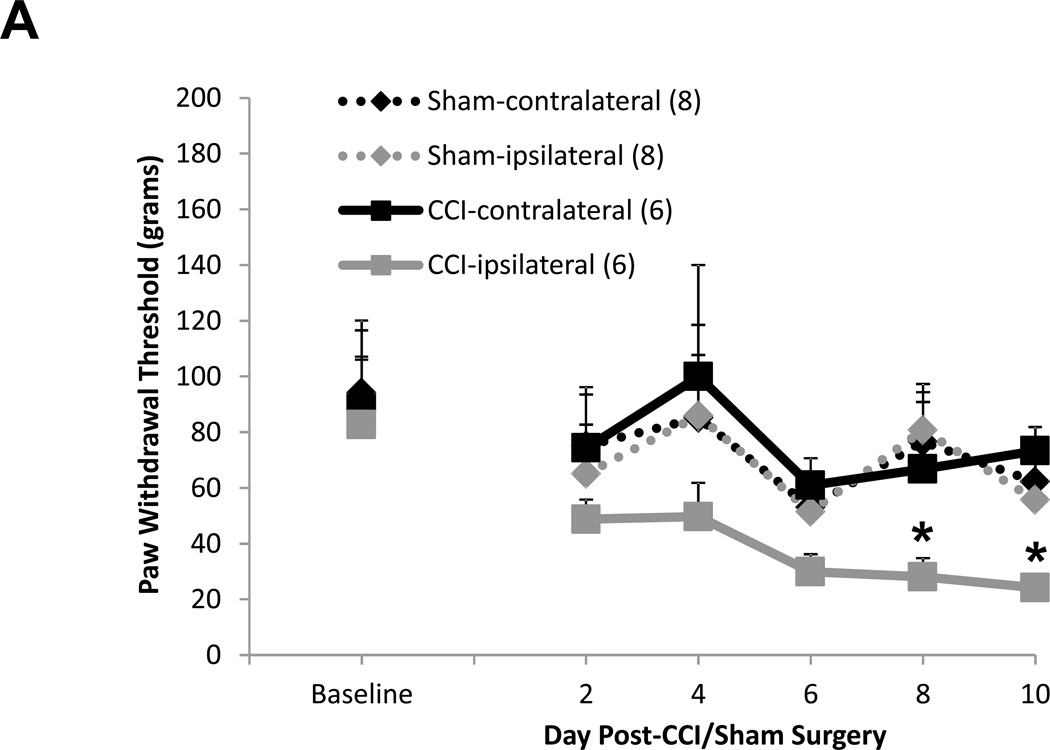

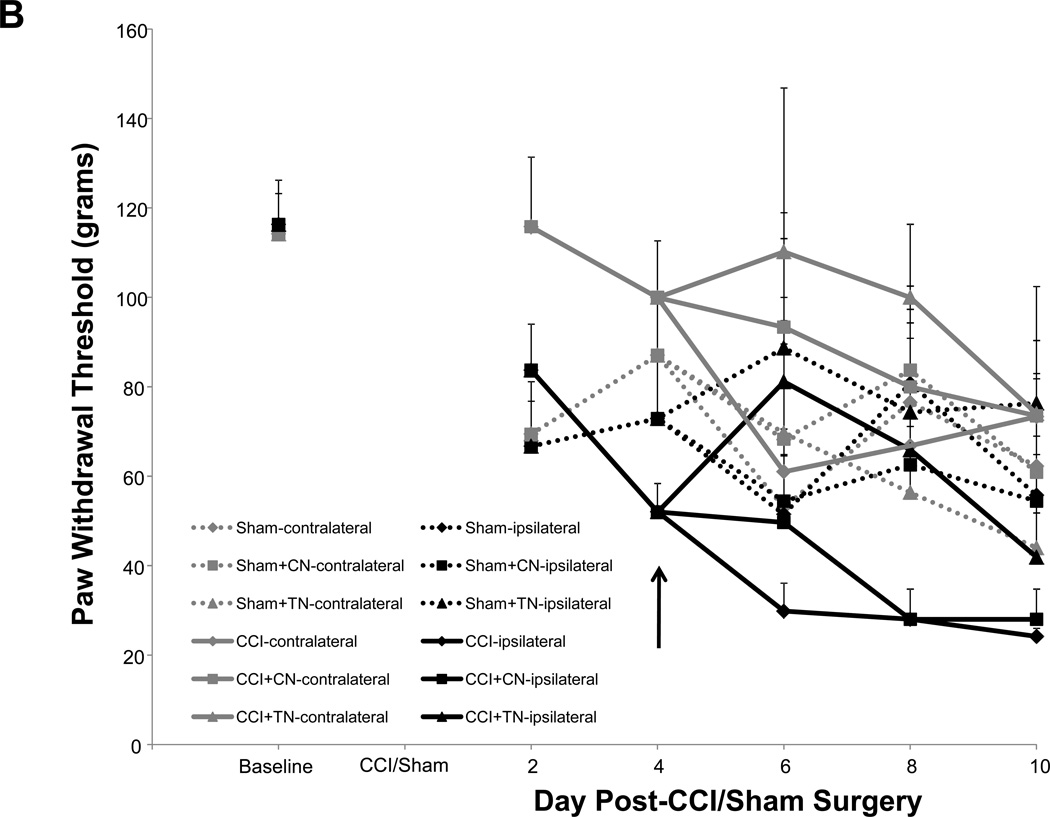

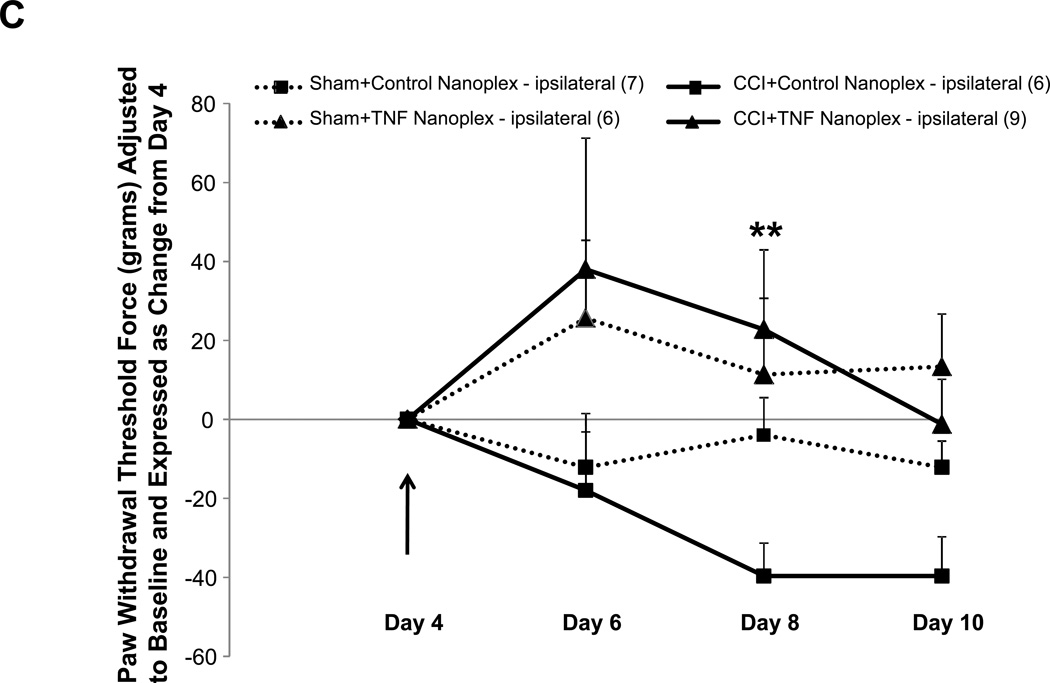

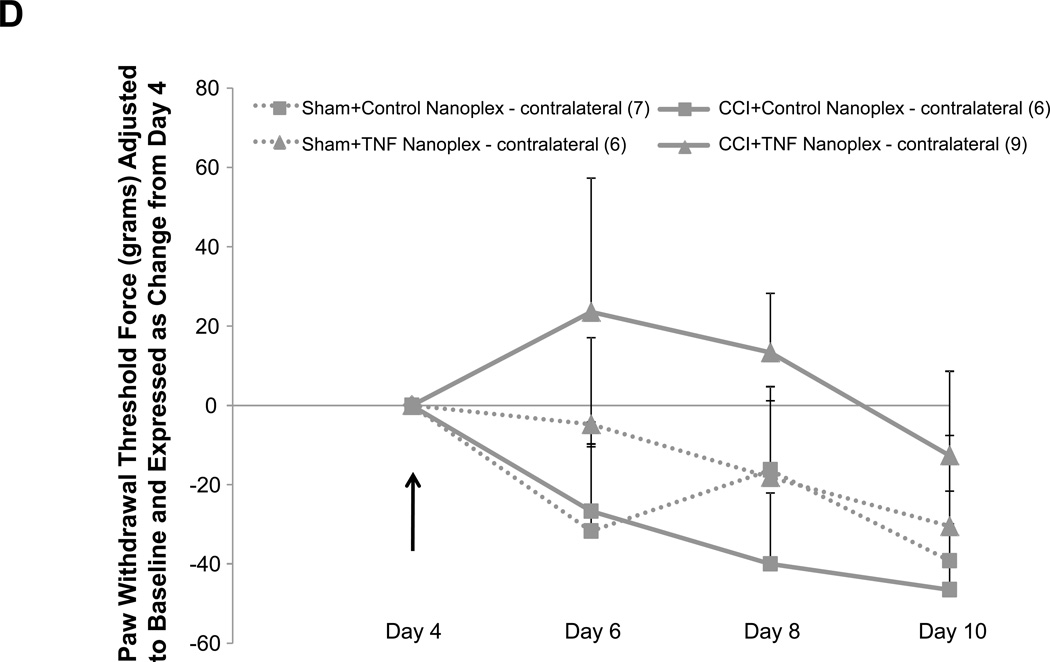

3.3. TNF nanoplexes prevent mechanical allodynia

Allodynia developed in rats that received CCI, but not in sham-operated rats (Fig. 4A). Rats receiving CCI had lower withdrawal thresholds at days 8 and 10 post-ligature placement as compared to their respective hind paw baseline scores (Fig. 4A), whereas the contralateral hind paw of CCI rats and both sham-operated rat hind paws showed no differences for mechanical threshold (Fig. 4A). As presented in figure 4B, the overall average baseline values for mechanical withdrawal threshold were 116.3 ± 9.9 grams for ipsilateral and 114.2 ± 9.0 grams for contralateral hind paws. However, unlike thermal hyperalgesia baseline scores that were relatively consistent amongst sub-groups (Table 1), when analyzed separately, it became apparent that baseline mechanical threshold scores varied across groups (Table 2). Due to these unintentional and uncontrollable differences in the baseline scores observed amongst the various groups of animals, raw data scores at each time point for each group that are depicted in figure 4B were adjusted to respective baseline values (at the time of surgery) and expressed as the change in paw withdrawal threshold force (grams) from baseline for subsequent multivariate analysis with raw baseline values considered as covariates in the model analysis. Repeated measures mixed model analysis determined, albeit slight, a Time × Treatment interaction for the ipsilateral hind paws at F(6.64, 116.23) = 2.09, p = 0.05, and a main between-subjects effect for (CCI vs Sham) surgery, F(1, 35) = 18.55, p < 0.001 (Fig. 4A). It should be noted that, when the baselines are taken into account for each sub-group’s hind paws, the data ‘normalizes’ such that it would not make a difference which sub-group the animals were placed into; for example, the CCI group (baseline values 82.6 ± 23.4 grams, Table 2) as compared to the CCI + TNF nanoplex group (baseline values 148.9 ± 24.9 grams, Table 2) have equivalent range of values for allodynia over time (prior to nanoplex injection) when the data (shown in Fig. 4B) is expressed as change from baseline: CCI (−30 to −70 grams force) and CCI + TNF nanoplex (−40 to −100 grams force). Normalized values for all sub-group non-operated contralateral hind paws ranged from 0 to −30 grams force (prior to surgical manipulation for nanoplexes).

Figure 4. Assessment of mechanical allodynia in the CCI model of neuropathic pain.

(A). Mechanical allodynia for sham-operated and CCI rats. CCI rats developed ipsilateral hind paw mechanical allodynia at days-8 and 10 post-ligature placement. Initial 2 × 2 factorial repeated measures ANOVA analysis determined a time effect, F(1.920, 46.089) = 5.369, p = 0.009, with no main Group or Hind paw effect and no interaction effects. To determine within which group and hind paw the time effect occurred, one-way ANOVA repeated measures analysis was performed for both ipsilateral and contralateral hind paw data (CCI vs Sham) followed by post-hoc paired t-test revealing * p < 0.05 for comparison between baseline and post-operative values within the CCI-ipsilateral hind paw. (B) Raw data for hind paw withdrawal threshold (grams force) for all groups are presented as averaged values. Baseline recordings using calibrated Semmes-Weinstein (von Frey) monofilaments were determined before experimental manipulation for all animals and are expressed as the mean of three separate trials (Baseline), taken three days prior to surgery (baseline right hind paw = 116.3 ± 9.9 and left hind paw = 114.2 ± 9.0 grams) for all rats (n=42). Days 2 and 4 post-surgery, data presented for CCI averaged left hind paw values and averaged right hind paw values (n=21); same for sham-operated (n=21) rats. Data are presented for each sub group (sham, sham+control nanoplex, sham+TNF nanoplex, CCI, CCI+control nanoplex, CCI+TNF nanoplex) on days 6, 8 and 10 as averaged left hind paw values and right hind paw values (n=6–9/group). Each point is expressed as the mean ± SEM. Arrows indicate day of contralateral intra-hippocampal (CA1 region) microinjection (relative to CCI, day 0) of GNR-scrambled siRNACy3 (control nanoplex, CN) or GNR-TNF siRNACy3 (TNF nanoplex, TN); microinjection occurred after assessment of nociceptive behavior. (C) and (D): Data, adjusted for baseline values, are expressed as the change in paw withdrawal threshold force (grams) from day 4 post-CCI/sham values (recordings taken prior to intra-hippocampal nanoplex injection. A mixed-effect model for repeated measures analysis was used to assess the effect of nanoplex treatment on mechanical allodynia. In order to account for differences in hind paw baseline values between animal groups, all data was initially expressed as change from baseline and analyzed with raw baseline values considered as covariates in the model. To observe the effect of treatment, data in (C) and (D) are expressed as change from day-4, which was the new baseline value whereby withdrawal recordings were taken just prior to contralateral intra-hippocampal injection (none, Control Nanoplex, TNF Nanoplex). There was no within-subject time effect, and between-subject analysis showed no Surgery X Treatment effect and no overall Surgery effect, but there was an overall ipsilateral (right) hind paw Treatment effect: F(2, 36)=3.38, p < 0.05. Subsequent One-way ANOVA followed by LSD post-hoc analysis with planned contrasts, ** p < 0.01. Arrow indicates day of intra-hippocampal injection. Positive error bars indicate SEM. In each panel, the number of animals in each group (n) is indicated in parentheses.

Table 2.

Baseline hind paw withdrawal threshold scores (in grams force) for mechanical allodynia.

| Group | Ipsilateral | Contralateral | N# |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sham Groups | |||

| Sham | 84.8 ± 22.3 | 94.1 ± 25.9 | 8 |

| Sham + CN | 98.4 ± 13.0 | 93.2 ± 11.8 | 7 |

| Sham + TN | 102.6 ± 22.5 | 124.4 ± 16.3 | 6 |

| CCI Groups | |||

| CCI | 82.6 ± 23.4 | 88.3 ± 28.2 | 6 |

| CCI + CN | 177.8 ± 16.4+** | 155.6 ± 23.1 | 6 |

| CCI + TN | 148.9 ± 24.9* | 131.1 ± 18.9 | 9 |

| All Rats | 116.3 ± 9.9 | 114.2 ± 9.0 | 42 |

One-way ANOVA followed by LSD post-hoc analysis of baseline scores amongst all groups for ipsilateral hind paws revealed:

p < 0.05 vs Sham+CN and Sham+TN;

p < 0.05 vs Sham and CCI;

p < 0.01 vs Sham and CCI.

Abbreviations: CN = control nanoplex; TN = TNF nanoplex; CCI = chronic constriction injury.

In order to determine the effect of the nanoplex treatment on mechanical allodynia, subsequent analysis using baseline-adjusted data was further adjusted to day-4 threshold scores (Fig. 4C and D). Control nanoplex microinjection into the CA1 region of the contralateral (left) hippocampus four days following CCI had no effect on development of mechanical allodynia (Fig. 4B–D). CCI rats receiving CA1 contralateral hippocampal TNF nanoplex microinjection four days post-CCI demonstrated an effect at day 8 post-ligature placement indicating the prevention of allodynia; but, this was transient implying delayed onset of mechanical allodynia (Fig. 4C). An initial mixed model (ANCOVA) repeated measures analysis determined that there was no within-subject time effect, and between-subject analysis showed no Surgery × Treatment effect and no overall Surgery effect, but there was an overall ipsilateral (right) hind paw Treatment effect: F(2, 36)=3.38, p < 0.05. Subsequent one-way ANOVA analysis with planned contrasts by LSD post-hoc analysis revealed for Day 8: sham+control nanoplex vs CCI+control nanoplex, p = 0.140 (NS); sham+TNF nanoplex vs CCI+TNF nanoplex, p = 0.612 (NS); CCI+control nanoplex vs CCI+TNF nanoplex, ** p < 0.01. Similar planned contrasts for days 6 and 10 were not different.

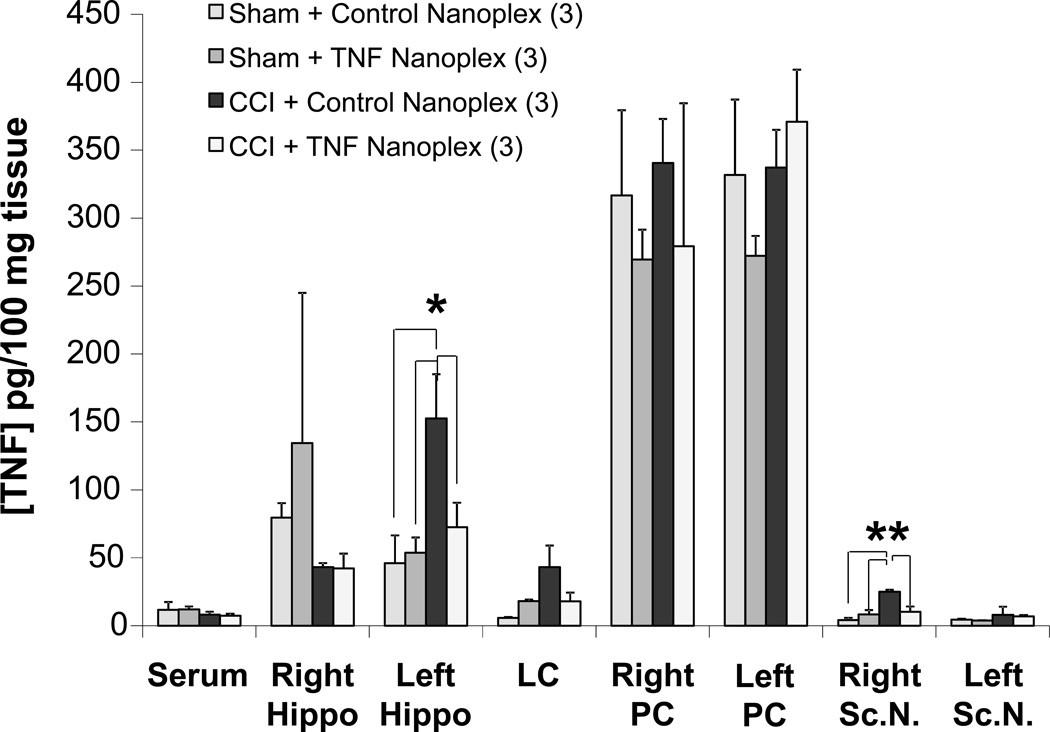

3.4. TNF nanoplexes decrease hippocampal TNF protein

Similar to the results for TNF levels in CCI as compared to sham rats shown in figure 2, TNF levels were increased 3-fold in the CCI rats receiving control nanoplexes in the contralateral hippocampus (152.6 ± 32.5 pg/100 mg tissue) compared to TNF levels in hippocampi from sham-operated rats microinjected with either the control or TNF nanoplexes (46 ± 20.5 pg/100 mg tissue and 53.8 ± 11.2 pg/100 mg tissue, respectively) (Fig. 5). CCI rats microinjected with TNF nanoplexes into the contralateral hippocampal CA1 region demonstrated a decrease in the production of TNF (72.5 ± 18.1 pg/100 mg tissue) in the contralateral hippocampus as compared to CCI rats receiving the control nanoplexes (Fig. 5). Thus, our TNF silencing therapy was effective. Furthermore, a decrease in bioactive TNF does not occur in other areas of the brain investigated (Fig. 5). This confirms that TNF nanoplexes were injected into the targeted region of the brain and remained localized to the contralateral hippocampus.

Figure 5. Silencing of bioactive TNF production by GNR-TNF siRNACy3 (TNF nanoplex) microinjection into the contralateral hippocampal CA1 region on day-4 post-CCI, as assessed on day-10 post-CCI.

Data represents the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments. To assess the effect of contralateral intra-hippocampal nanoplexes on TNF levels, values from sham rats microinjected with either control or TNF nanoplexes were compared to the CCI control group represented by CCI rats microinjected with control nanoplexes and the CCI experimental group, CCI rats injected with TNF nanoplexes. Statistical significance indicated (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01) was by ANOVA, followed with Bonferroni t-test. CCI = chronic constriction injury; Rt. Hippo = right hippocampus; LC = locus coeruleus; PC = parietal cortex; Sc.N. = sciatic nerve; PC was assayed as a control region to test for diffusion effects. The n for the group is indicated in parentheses.

TNF levels in the ipsilateral sciatic nerve were increased in the CCI rats that received the contralateral intra-hippocampal control nanoplexes when compared to sham+control nanoplex rats (25.1 ± 1.4 pg/100 mg tissue vs 4.2 ± 1.6 pg/100 mg tissue, respectively, p < 0.01, ANOVA; Fig. 5). CCI rats microinjected with TNF nanoplexes into the contralateral hippocampal CA1 region demonstrate a decrease in TNF levels in the ipsilateral (right) sciatic nerve (10.2 ± 3.9 pg/100 mg tissue; Fig. 5). As also shown in figure 5, there was no effect elicited by nanoplex injection into the hippocampus on peripheral serum levels of TNF. In addition, the lack of any change of serum TNF levels in response to CCI +/− TNF nanoplex treatment indicates that systemic TNF release could not account for the increased TNF levels in the brain. Therefore, these results demonstrate that it is specifically TNF of the brain, and particularly of the hippocampus, that contributes to nociception.

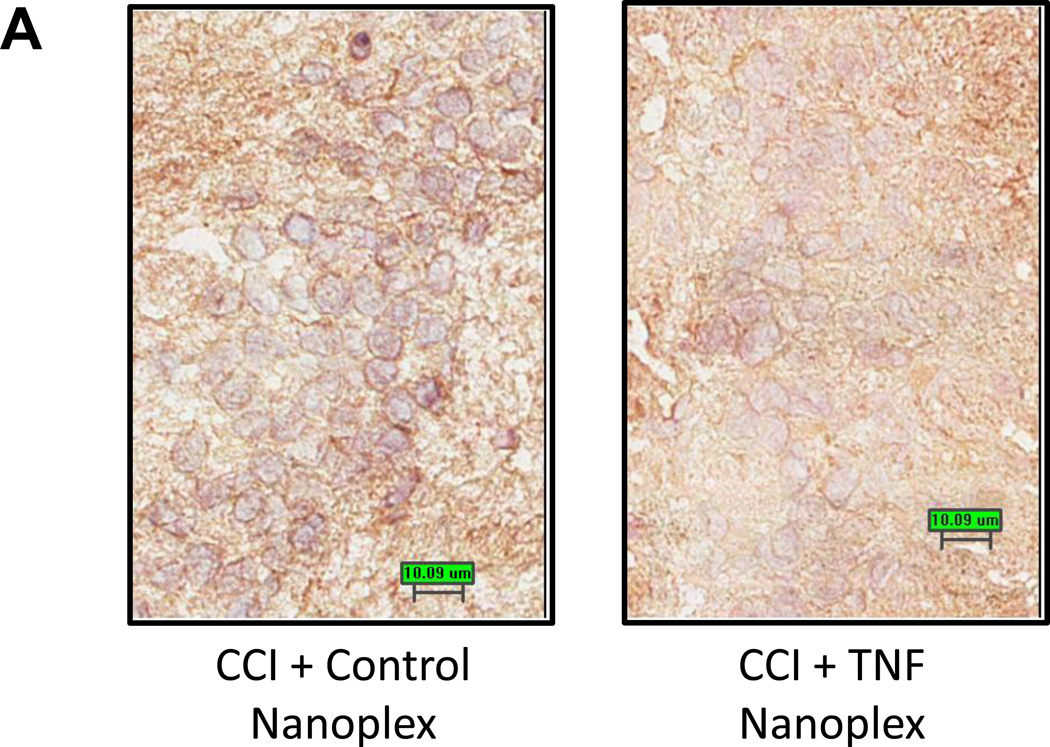

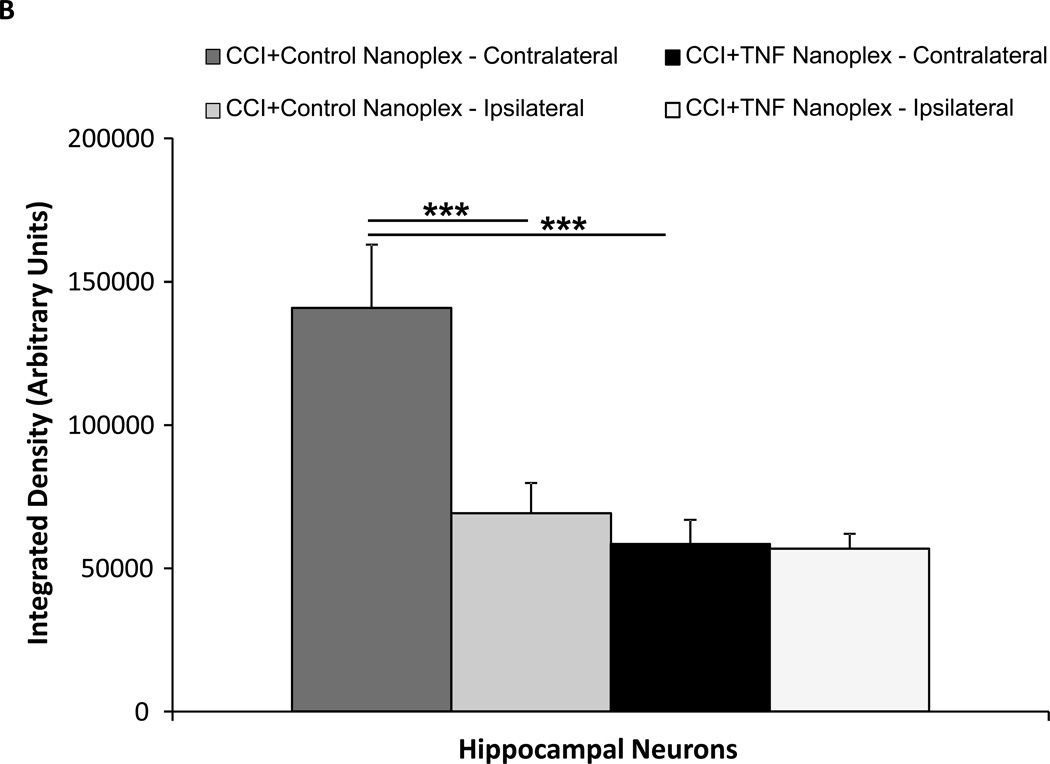

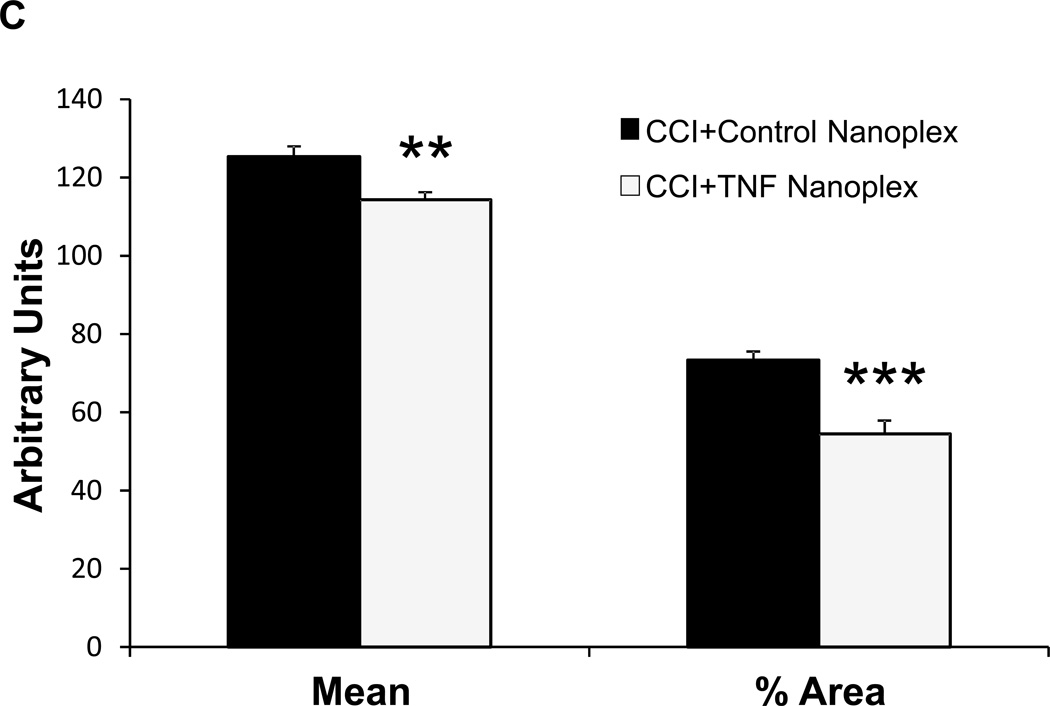

3.5. TNF nanoplexes decrease immunoreactivity for hippocampal TNF

Microinjection of TNF nanoplexes into the contralateral hippocampus of rats four days post-CCI reduced the amount of immunoreactivity for TNF in the hippocampus compared to control nanoplex injection (Fig. 6A) at 10 days post-CCI. Quantitative analysis of TNF staining in both hippocampi (right, ipsilateral and left, contralateral) demonstrated an increase in TNF staining in the contralateral hippocampus of CCI rats receiving the control nanoplex compared to the ipsilateral hippocampus from the same animals, as well as to the contralateral hippocampi from CCI rats that received the TNF nanoplex (Fig. 6B). These results correlate well with the TNF bioassay results presented in figure 5. Analysis of image integration density (sum of the values of the pixels in the selected image; equivalent to Area × Mean Gray Value) using ANOVA followed by the Tukey Test for multiple comparisons clearly revealed distinct differences between the contralateral and ipsilateral hippocampi within the CCI control nanoplex injected rats (p < 0.001) and between control nanoplex compared to TNF nanoplex injected CCI rats within the contralateral hippocampus (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Immunohistochemical staining for TNF.

(A) TNF immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of CCI day-10 rats following contralateral CA1 hippocampal injection (on day-4 post-CCI) of either the control nanoplex (left panel) or the TNF nanoplex (right panel) (0.2 nmol/4 µl). Data is representative of three separate experiments. Scale bar = 10µm. (B) Quantitative analysis for TNF staining in hippocampal neurons. Individual neurons (10 neurons/hippocampal section) were selected for analysis and results compared between the TNF nanoplex and the control nanoplex hippocampal-injected rats. Results are presented for integration density values (sum of the values of the pixels in the selected image; equivalent to Area × Mean Gray Value). One-way ANOVA analysis followed by pairwise multiple comparisons with Tukey Test for post-hoc analysis revealed differences as follows: *** p < 0.001, left (contralateral) vs right (ipsilateral) within the control nanoplex group, and *** p < 0.001, control nanoplex vs TNF nanoplex between the contralateral hippocampi. (C) Comparison of quantitative analysis Mean and % Area values of the contralateral hippocampal sections from n = 3 rats/group. Analysis of staining in individual neurons (10 neurons/section, 1–2 sections per rat; 50 neurons total/group) was compared between the TNF nanoplex and the control nanoplex contralateral hippocampal sections. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01 as compared to respective controls, Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test.

Based on these results, subsequent analyses for all animals (n=3) in each group compared TNF staining in the contralateral hippocampi only. Further quantitative analysis of neuron TNF staining in the contralateral hippocampal sections determined that the compartmentalization of neuronal TNF synthesis as per assessment of the percent area (percentage of pixels in the selected image) and mean intensity (sum of the values of all the pixels in the selection divided by the number of pixels) values of the individual neurons in the stained tissue were also different between the two groups (Fig. 6C).

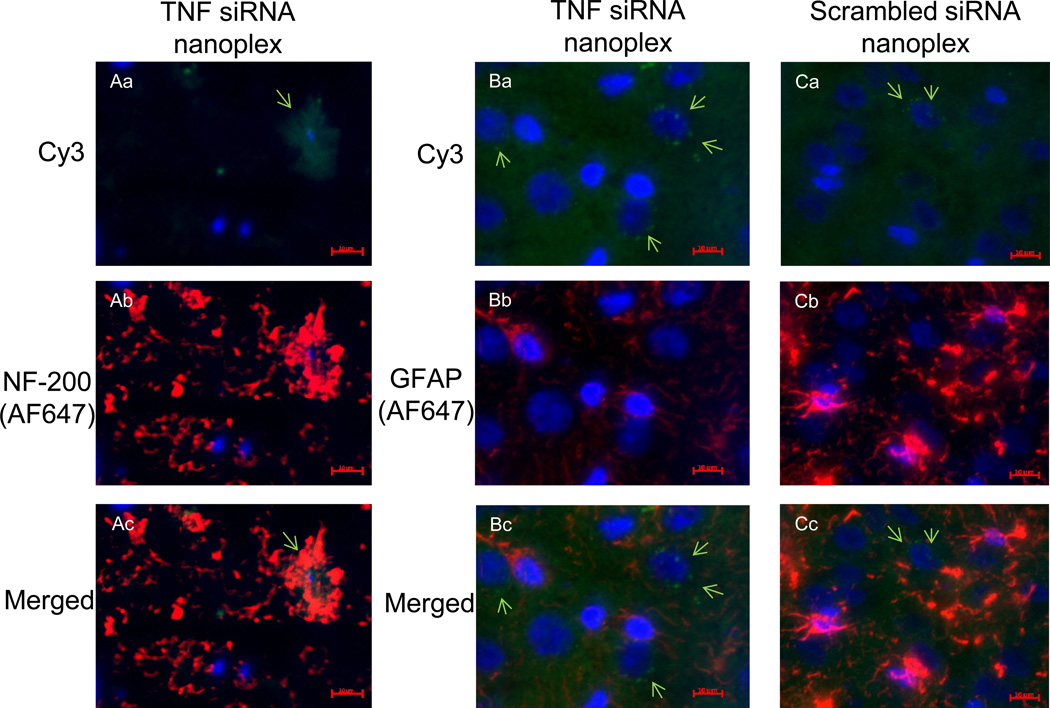

3.6. Co-localization of siRNACy3 occurs with neurons

To determine the cell type(s) associated with nanoplex uptake, rat coronal hippocampal sections were labeled with primary antibodies to either glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (glial cells) or neurofilament-200 (NF-200) (neurons) [6, 46]. Visualization of the primary antibody labeling was achieved using an IgG1-AlexaFluor 647 (AF-647) secondary antibody, with the excitation/emission maxima at 650/668 nm. Visualization of scrambled siRNACy3 or TNF siRNACy3 uptake by hippocampal cells in the same tissue sections was by Cy3 fluorescence (excitation/emission maxima of 514/566 nm) (Fig. 7). The perinuclear siRNACy3 staining together with NF-200 staining (Fig. 7, panel Ac) indicates siRNACy3 uptake by neurons (NF-200 positive co-localization); the punctate, perinuclear siRNACy3 staining in panels Ba and Ca, in the absence of GFAP positive co-localization (panels Bb and Bc; Cb and Cc), implies lack of siRNACy3 uptake into glial cells.

Figure 7. Immunofluorescence staining.

Immunofluorescent labeling shows nanoplex co-localization in rat coronal hippocampal sections. Nanoplexes, comprised of siRNA labeled with Cy3, were injected into the contralateral hippocampal CA1 region of CCI rats. The hippocampi were isolated six days later and frozen tissue sections were prepared. Identification of cell type was by immunofluorescent staining (4–6 µm section, acetone-fixed). Column A: Localization of Cy3 and NF-200 staining. GNR-TNF siRNA nanoplex-Cy3 staining (green) and nuclear (Hoechst dye) blue staining (panel Aa); Neurofilament-200, NF-200 staining for neurons using goat anti-mouse IgG1-AlexaFluor 647 secondary antibody (red; panel Ab); and overlay of images (panel Ac) shows co-localization. Column B: Visualization of GNR-TNF nanoplex-Cy3 staining (green) and nuclear blue staining (panel Ba); Glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP staining for glial cells (panel Bb) using goat anti-mouse IgG1-AlexaFluor 647 secondary antibody (indicated as red); overlay of images (panel Bc) shows lack of co-localization. Column C: Visualization of GNR-scrambled siRNA (control) nanoplex-Cy3 staining (green) and nuclear blue staining (panel Ca); GFAP staining for glial cells (panel Cb) using goat anti-mouse IgG1-AlexaFluor 647 secondary antibody (red); overlay of images (panel Cc) shows lack of co-localization. Data is representative of three replicate experiments. Scale bar = 10 µm.

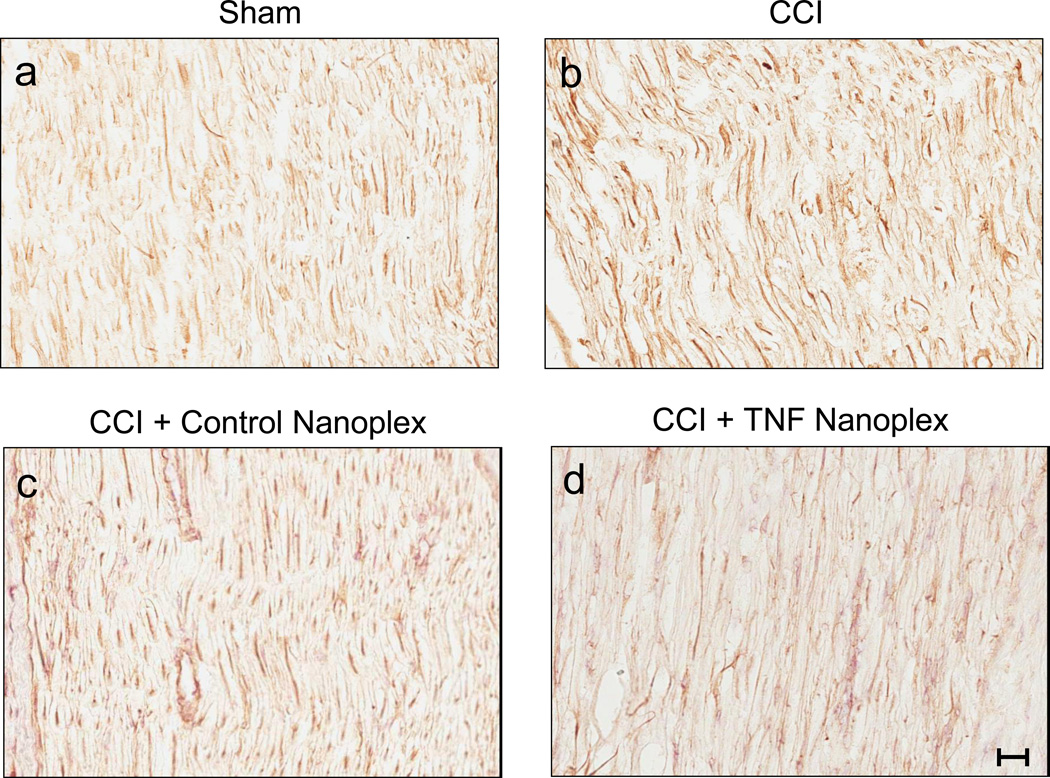

3.7. Hippocampus delivered TNF nanoplexes do not decrease immunoreactivity for TNF in the ipsilateral sciatic nerve

Comparison of staining for TNF amongst ipsilateral sciatic nerve tissue sections from sham rats and CCI rat groups at 10 days post-surgery is shown in figure 8. Microinjection of TNF nanoplexes into the contralateral hippocampus of rats four days post-CCI did not reduce the amount of immunoreactivity for TNF in the ipsilateral sciatic nerve at 10 days post-CCI (Fig. 8). Quantitative analysis of TNF staining in CCI rat group (CCI, CCI+control nanoplex, CCI+TNF nanoplex) sciatic nerve sections (average of 6–9 imaged areas/sciatic nerve section from 3 individual rats per group) demonstrated no differences for integration density (p = 0.35, 0.23, and 0.29, respectively) and mean staining intensity (p = 0.19, 0.13, and 0.14, respectively) values as compared to sham rat sciatic nerves (ANOVA with Dunnett t-test for comparison to sham control). Further quantitative analysis of TNF staining in the ipsilateral sciatic nerve sections determined that the compartmentalization of TNF synthesis as per assessment of the percent area values was different for CCI (17.2 ± 0.3%, p < 0.05) and CCI rats receiving the intra-hippocampal control nanoplexes (5.2 ± 1.0%, p = 0.03), but was not different from CCI rats receiving contralateral CA1 hippocampal injection of the TNF nanoplex (5.8 ± 2.1%, p = 0.08) as compared to the sham group (11.2 ± 1.4%; ANOVA with Dunnett t-test for comparison to sham control). In these sections, TNF antibodies immunoreact with both vessels (endothelial cells express TNF), and axons that have been shown to express TNF, which increases after injury [62].

Figure 8. Immunoreactive staining for TNF in ipsilateral sciatic nerves from day-10 rats.

Shown in each panel is a representative section of sciatic nerve of three independent animals from the following groups: (a) Sham rats; (b) CCI rats; (c) CCI rats with contralateral CA1 hippocampal control nanoplex injection on day-4 post-ligature placement; and (d) CCI rats with contralateral CA1 hippocampal TNF nanoplex injection on day-4 post-ligature placement. All sections were scanned at 200× magnification. Scale bar = 50.95 µm.

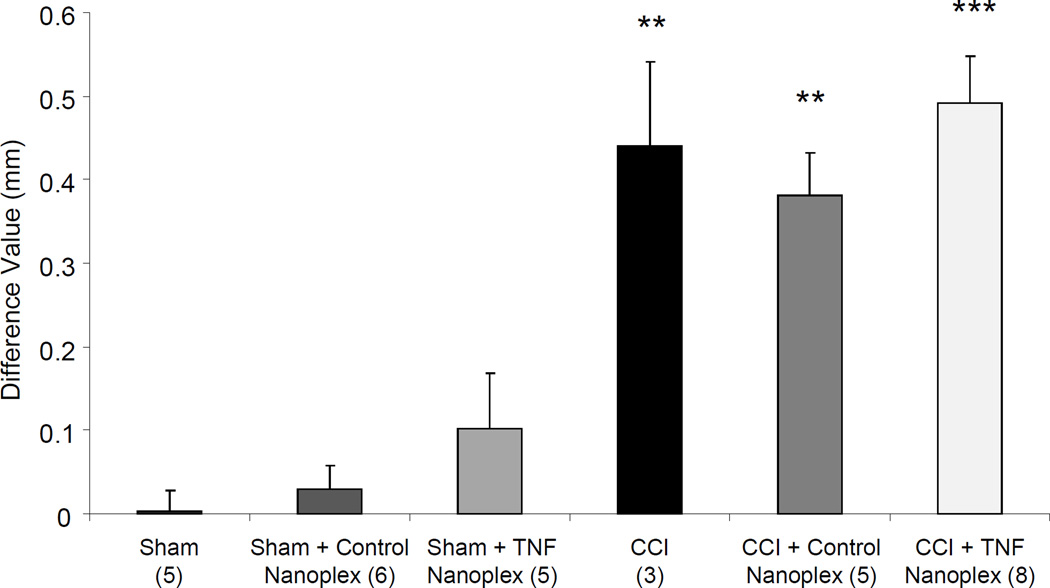

3.8. TNF nanoplexes do not affect sciatic nerve diameter

As a measure of edema, caliper measurements of the sciatic nerve, expressed as the difference between ipsilateral right sciatic nerve average diameter (mm) and contralateral left sciatic nerve average diameter (mm), were performed. Rats receiving sham surgeries had no change in ipsilateral sciatic nerve diameter compared to their contralateral/left sciatic nerve. Rats receiving CCI demonstrated an increase in ipsilateral nerve diameter, compared to their contralateral/left sciatic nerve (Fig. 9). The groups of sham rats with and without nanoplex injections into the contralateral hippocampus showed no differences in the diameters of their sciatic nerves. Conversely, all groups of CCI rats, with and without nanoplex injections, had increased ipsilateral sciatic nerve diameters compared to their contralateral/left sciatic nerve (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Caliper measurements of sciatic nerve diameters in rats at day-10 of sham or CCI, alone or with contralateral CA1 hippocampal nanoplex injection on day-4 post-surgery.

Three measurements each were recorded for proximal, ligatured, and distal sections of ipsilateral nerves, and averaged to give one value for nerve diameter; similar measurements were recorded for contralateral nerves. Data are presented as the difference of averaged ipsilateral (experimental)-averaged contralateral (control) nerve diameter (mm). Each bar is expressed as the mean ± SEM. Data was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey multiple comparison tests: **p ≤ 0.01 compared to all three Sham groups; ***p < 0.001 compared to all three Sham groups. Note: CCI causes increases in the diameter of the ipsilateral sciatic nerves, which remains unaffected by TNF nanoplex therapy. The n for the group is indicated in parentheses.

3.9. TNF mRNA of the hippocampus

Hippocampal TNF gene expression was assessed employing qRT-PCR. Results from contralateral hippocampi obtained from untreated rats at day-10 post-CCI did not differ in TNF gene expression compared to contralateral hippocampi from rats with sham surgery (17 ± 8% increase, p = 0.12, Student’s t-test).

The effect of TNF nanoplexes on hippocampal TNF mRNA was also evaluated. Rats undergoing CCI and receiving contralateral intra-hippocampal CA1 injection of TNF nanoplexes four days later demonstrated no apparent decrease in TNF gene expression as compared to CCI rats alone and CCI rats receiving control nanoplex injection, as assessed six days later on day-10 post-CCI (8 ± 4% inhibition, p = 0.15, NS).

4. Discussion

This rat sciatic nerve CCI study demonstrates that selective silencing of hippocampal TNF expression by TNF siRNA nanoplexes results in robust reduction of hyperalgesia and modest reduction in mechanical allodynia, behavioral hallmarks of neuropathic pain. Previously, we showed that unilateral CCI is associated with increased brain TNF production, specifically in the locus coeruleus and hippocampi [16]. We now determined that CCI to the right sciatic nerve is associated with increased TNF production specifically in the contralateral (left) hippocampus. Therefore, we precisely targeted our nanoplex therapy to the contralateral hippocampus. While unilateral CCI surgery with contralateral nanoplex injections on both sides was not performed, we previously reported that selectively increasing TNF production in both the right and left hippocampi resulted in development of bilateral peripheral hind paw sensitivity [46]. Based on the above and reports of lateralization [18, 42, 83], future studies are warranted to determine whether similar effects on nociceptive behavior occur for either side/hippocampus.

Our findings clearly show that increased hippocampal TNF production mediates objective behavior parameters indicative of chronic pain. Furthermore, the rapid and sustained decrease in thermal hyperalgesia that occurred with TNF nanoplex injection following CCI suggests a possible therapeutic strategy. Decreased mechanical allodynia only occurred on day-8 post-CCI in rats receiving a contralateral hippocampal TNF nanoplex injection on day-4 post-CCI. Analysis of a larger sample set and/or a longer timeline of readings will be more informative. Additionally, the nanoplex injection in this study specifically targeted the CA1 hippocampal region. It is possible that directing TNF nanoplexes to another region(s) of the hippocampus (i.e., CA3 or dentate gyrus) or targeting multiple regions at once may produce greater relief of mechanical allodynia. Nonetheless, silencing of TNF production in the contralateral hippocampus prevented, or delayed the onset of, mechanical allodynia induced by CCI.

Immunoreactivity for TNF in the ipsilateral sciatic nerve did not differ between sham-operated and CCI rats at day-10 post-surgery. These findings support the results for bioactive TNF levels in the ipsilateral sciatic nerve of CCI rats at day-10. However, the ‘treatment control’ CCI rat group with contralateral CA1 control nanoplex injection did experience elevated bioactive TNF levels in the ipsilateral sciatic nerve. Importantly, contralateral intra-hippocampal TNF nanoplex injection decreased CCI-induced bioactive TNF levels (in contralateral hippocampus and ipsilateral sciatic nerve) and completely alleviated thermal hyperalgesia, as well as delayed development of mechanical allodynia. Since hyperalgesia and allodynia differ for time of onset and TNF nanoplex therapy was more effective for hyperalgesia than allodynia, these findings suggest that thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia are separate mechanisms [1, 5]. However, our findings support that both symptoms of chronic pain syndromes require hippocampal TNF production.

Similar to TNF staining, the CCI-induced increase in ipsilateral sciatic nerve diameter remained unaffected by TNF nanoplex therapy. Thus, injection of TNF nanoplexes into the contralateral hippocampus does not exert a direct effect on peripheral nerve inflammation, but may indirectly affect TNF production in the periphery through compensatory changes in sympathetic efferent pathways, possibly influencing macrophage production of TNF at the peripheral injury site [48, 63, 70]. Consequently, alleviation of hyperalgesia and transient prevention of allodynia are mediated by direct injection of TNF nanoplexes into the hippocampus, independent of peripheral TNF levels, demonstrating the importance of the hippocampus in pain perception.

We previously reported that increasing brain TNF expression is sufficient for the development of hind paw hypersensitivity in rats [33, 46]. We also demonstrated a neuromodulator role for TNF: (1) TNF is produced in the hippocampus [16, 17, 34, 54, 69, 70]; (2) tricyclic antidepressants used to treat neuropathic pain (i.e., amitriptyline), decrease brain TNF expression [34, 70], and (3) TNF inhibits hippocampal norepinephrine release [16, 34–36, 55, 56]. Receptors for TNF (TNFR-1, p55TNFR and TNFR-2, p75TNFR) are constitutively expressed on all neuron cell types [20, 85]. Based on our findings and contemporary literature, we propose that enhanced TNF production within the hippocampus contributes to ongoing inflammatory responses, associated neuroplastic changes, and development of the central sensitization of neuropathic pain.

Our premise is that over-expression of brain TNF mediates chronic pain. Several antidepressants decrease TNF in the brain [10, 34, 56, 70]. Microinjection of an antidepressant into the contralateral primary somatosensory cortex, another brain region involved in the pain network [8], blocked hyperalgesia in nerve-ligated rats [47]. However, antidepressant drugs have multiple side-effects. Since TNF is pleiotropic, inhibits norepinephrine release, and triggers a cascade of cytokines involved in neuropathic pain development [45, 59], selective inhibition of TNF production would prevent induction of subsequent cytokines and enhance monoamine release, a central mechanism attributed to antidepressant and analgesic drugs. Furthermore, feed-back activation of the transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), which controls genes that encode TNF [71], can be averted, thereby disrupting the “vicious neuropathic pain cycle”. A novel strategy is to focus on a targeting system with limited alternative responses and at a site where nociception is processed.

The hippocampus is well-positioned within the brain for pain processing and modulation; it receives both direct and indirect nociceptive inputs of pain through ascending pathways and modulates nociceptive processing through activation of descending pain pathways [22–24, 40, 72]. The hippocampal CA1 region was targeted due to neurons in this region responding to pain stimuli. The hippocampal CA1 region and dentate gyrus process persistent pain [65]. Our laboratory has provided direct evidence for TNF and indirect evidence for hippocampal involvement in neuropathic pain development. Continuous intracerebroventricular (icv) microinfusion of rrTNF into the lateral cerebral ventricle adjacent to the hippocampus induces pain behavior in naïve rats, while enhancing and prolonging pain behaviors in CCI rats [33, 70]. Similarly, icv injection of rrTNF into the brains of naïve rats produces thermal hyperalgesia [51]. In contrast, rats with CCI that receive icv continuous microinfusion of TNF antibodies, which block TNF bioactivity, demonstrate complete abolishment of hyperalgesia if the infusion is begun on day-4 post-CCI [33]. Likewise, Sommer et al. [68] determined that day-4 post-CCI was an important window for treatment of neuropathic pain behaviors with thalidomide (inhibits TNF synthesis). The present study was designed to reduce hippocampal TNF based on the time frame for alleviating nociceptive behaviors in the CCI model.

There is direct evidence for hippocampal TNF involvement in neuropathic pain pathogenesis. Injection of rTNF into the hippocampus of naïve rats induces memory deficits and impairment in CA1 synapse function similar to that induced by peripheral nerve injury [54]. We demonstrated that transfection of TNF-producing cDNA plasmids into cells of the hippocampal CA1 region of naïve rats induces nociceptive behaviors observed in neuropathic pain syndromes [46]. Thus, enhanced hippocampal TNF production is sufficient to induce nociceptive behaviors.

This study has been designed to assess the central effect of TNF-inhibiting siRNA on nociceptive behavior and TNF protein production. A solitary direct injection of single stranded TNF siRNA into the somatosensory cortex resulted in a 37% decrease in TNF mRNA, producing a short-lived, marginally effective behavioral change [73]. Conversely, 14-day icv infusion of siRNA targeting the dopamine or serotonin transporter in rat brains resulted in widespread silencing of these receptors [75, 76]. In order to circumvent the limitations of siRNA, we used siRNA-nanoparticle complexes. Functionalized GNRs have been used to deliver siRNA, demonstrating effective silencing of hippocampal GAPDH gene expression for up to 11 days [6].

We and others previously determined that development of thermal hyperalgesia and an increase in hippocampal TNF levels occurs early (days 2–8) after CCI [16, 17, 33, 68]. In the present study, TNF mRNA was only marginally increased in the hippocampus at day-10 post-CCI; thus, even a marginal reduction (by TNF-inhibiting siRNA) might be expected to have effects on behavior and protein production. In fact, PCR results showed that contralateral hippocampal TNF gene expression was only marginally decreased six days after TNF nanoplex injection, whereas TNF bioactive protein production was greatly reduced, as was nociceptive behavior. Thus, a small decrease in mRNA coincided with large reduction in (TNF) protein production. In the future, separation of the CA1 region from the CA3-DG regions of the hippocampi may produce more definitive results for measurement of mRNA. Alternatively, a TNF siRNA-induced, microRNA-like translational repression effect (in absence of mRNA degradation) may be plausible [79]. While we cannot assess the number of neurons transfected with the siRNA, the findings for TNF staining in the hippocampus (Figs. 6B and C) clearly demonstrate that TNF production in the neuron is decreased with hippocampal CA1 injection of TNF-siRNA nanoplexes.

The present study demonstrates that increased TNF production in the hippocampus is not only sufficient but also necessary for hyperalgesia and allodynia. We conclude that decreasing hippocampal TNF inhibits two of the behavioral components of neuropathic pain, demonstrating an efficacious chronic pain therapy that targets brain-TNF synthesis through the use of cutting-edge biotechnology. Therapeutic nanoplexes may lead to development of a safe and long-lasting silencing of TNF without detrimental systemic side effects. Further investigation into strategies whereby either functionalized nanoplexes could be employed for systemic delivery of anti-TNF therapeutics to specific brain regions or alternative methods, such as perispinal delivery that has successfully been used for etanercept delivery to the brain, is warranted [77, 78].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University at Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in partial fulfillment of the MA degree in Pathology (E.G.) and by NIH grants R01HL048889 and R21AI084410 (PRK). The authors wish to thank Dr. James Earl Bergey, Department of Chemistry and ILPB, for his helpful discussions. NanoAxis, LLC positions that were served in an unpaid capacity during the undertaking of this research are as follows: Research and Development Directors (R.N.S., T.A.I.) and Scientific Advisory Board Members (P.R.K., P.N.P.). The article represents the authors’ own work in which NanoAxis, LLC was not involved. We acknowledge the assistance of the Confocal Microscope and Flow Cytometry Facility in the School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo. We are also extremely grateful to Dr. Alan Hutson, Professor and Chair of the Department of Biostatistics, for his consultation on the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

- 1.Baron R. Peripheral neuropathic pain: from mechanisms to symptoms. Clin J Pain. 2000;16(2 Suppl):S12–S20. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200006001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett GJ, Xie YK. A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33:87–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berridge MV, Herst PM, Tan AS. Tetrazolium dyes as tools in cell biology: new insights into their cellular reduction. Biotechnol Annu Rev. 2005;11:127–152. doi: 10.1016/S1387-2656(05)11004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bharali DJ, Klejbor I, Stachowiak EK, Dutta P, Roy I, Kaur N, Bergey EJ, Prasad PN, Stachowiak MK. Organically modified silica nanoparticles: A nonviral vector for in vivo gene delivery and expression in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11539–11544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504926102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block BM, Hurley RW, Raja SN. Mechanism-based therapies for pain. Drug News & Perspectives. 2004;17:172–186. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2004.17.3.829015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonoiu AC, Bergey EJ, Ding H, Hu R, Kumar R, Yong K-T, Prasad PN, Mahajan SD, Picchione KE, Bhattacharjee A, Ignatowski TA. Gold nanorod-siRNA induces efficient in vivo gene silencing in the rat hippocampus. Nanomedicine. 2011;6:617–630. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonoiu AC, Mahajan SD, Ding H, Roy I, Yong K-T, Kumar R, Hu R, Bergey EJ, Schwartz SA, Prasad PN. Nanotechnology approach for drug addiction therapy: Gene silencing using delivery of gold nanorod-siRNA nanoplex in dopaminergic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(14):5546–5550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901715106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks J, Tracey I. From nociception to pain perception: imaging the spinal and supraspinal pathways. J Anat. 2005;207:19–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bustin SA. Quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR): trends and problems. J Mol Endocrinol. 2002;1:23–39. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0290023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buttini M, Mir A, Appel K, Wiederhold KH, Limonta S, Gebicke-Haerter PJ, Boddeke HW. Lipopolysaccharide induces expression of tumour necrosis factor alpha in rat brain: inhibition by methylprednisolone and by rolipram. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122(7):1483–1489. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakravarthy KV, Bonoiu AC, Davis WG, Ranjan P, Ding H, Hu R, Bowzard JB, Bergey EJ, Katz JM, Knight PR, Sambhara S, Prasad PN. Gold nanorod delivery of an ssRNA immune activator inhibits pandemic H1N1 influenza viral replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10172–10177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914561107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen SP, Bogduk N, Dragovich A, Buckenmaier CC, Griffith S, Kurihara C, Raymond J, Richter PJ, Williams N, Yaksh TL. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response, and preclinical safety study of transforaminal epidural etanercept for the treatment of sciatica. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:116–126. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a05aa0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen SP, Wenzell D, Hurley RW, Kurihara C, Buckenmaier CCIII, Griffith S, Larkin TM, Dahl E, Morlando BJ. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response pilot study evaluating intradiscal etanercept in patients with chronic discogenic low back pain or lumbosacral radiculopathy. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:99–105. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000267518.20363.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connor EE, Mwamuka J, Gole A, Murphy CJ, Wyatt MD. Gold nanoparticles are taken up by human cells but do not cause acute cytotoxicity. SMALL. 2005;1(3):325–327. doi: 10.1002/smll.200400093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covey WC, Ignatowski TA, Knight PR, Spengler RN. Brain-derived TNFα: involvement in neuroplastic changes implicated in the conscious perception of persistent pain. Brain Res. 2000;859:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)01965-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Covey WC, Ignatowski TA, Renauld AE, Knight PR, Nader DN, Spengler RN. Expression of neuron-associated TNFα in the brain is increased during persistent pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:357–366. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2002.31930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diamond MC, Murphy GM, Akiyama K, Johnson RE. Morphologic hippocampal asymmetry in male and female rats. Exper Neurol. 1982;76:553–565. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(82)90124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding H, Yong K-T, Roy I, Pudavar HE, Law WC, Bergey EJ, Prasad PN. Gold nanorods coated with multilayer polyelectrolyte as contrast agents for multimodal imaging. J Phys Chem C. 2007;111(34):12552–12557. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dopp JM, Mackenzie-Graham A, Otero GC, Merrill JE. Differential expression, cytokine modulation, and specific functions of type-1 and type-2 tumor necrosis factor receptors in rat glia. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;75:104–112. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorn G, Patel S, Wotherspoon G, Hemmings-Mieszczak M, Barclay J, Natt FJC, Martin P, Bevan S, Fox A, Ganju P, Wishart W, Hall J. siRNA relieves chronic neuropathic pain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duric V, McCarson KE. Persistent pain produces stress-like alterations in hippocampal neurogenesis and gene expression. J Pain. 2006;7:544–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.01.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duric V, McCarson KE. Neurokinin-1 (NK-1) receptor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene expression is differentially modulated in the rat spinal dorsal horn and hippocampus during inflammatory pain. Mol Pain. 2007;3:32–39. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dutar P, Lamour Y, Jobert A. Activation of indentified septo-hippocampal neurons by noxious peripheral stimulation. Brain Res. 1985;328:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emad Y, Ragab Y, Zeinhorn F, El-Khouly G, Abou-Zeid A, Rasker JJ. Hippocampus dysfunction may explain symptoms of FM syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1371–1377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu AL, Yan XB, Sui L. Down-regulation of β1-adrenoceptors gene expression by short interfering RNA impairs the memory retrieval in the basolateral amygdala of rats. Neurosci Letters. 2007;428:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabay E, Tal M. Pain behavior and nerve electrophysiology in the CCI model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2004;110:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.George A, Marziniak M, Schäfers M, Toyka KV, Sommer C. Thalidomide treatment in chronic constrictive neuropathy decreases endoneurial tumor necrosis factor-α, increases interleukin-10 and has long-term effects on spinal cord dorsal horn met-enkephalin. Pain. 2000;88:267–275. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00333-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.George A, Schmidt C, Weishaupt A, Toyka KV, Sommer C. Serial determination of tumor necrosis factor-α content in rat sciatic nerve after chronic constriction injury. Exp Neurol. 1999;160:124–132. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hao S, Mata M, Glorioso JC, Fink DJ. Gene transfer to interfere with TNFα signaling in neuropathic pain. Gene Therapy. 2007;14:1010–1016. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hauck TS, Ghazani AA, Chan WC. Assessing the effect of surface chemistry on gold nanorod uptake, toxicity, and gene expression in mammalian cells. SMALL. 2008;4:153–159. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ignatowski TA, Covey WC, Knight PR, Severin CM, Nickola TJ, Spengler RN. Brain-derived TNFα mediates neuropathic pain. Brain Res. 1999;841:70–77. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ignatowski TA, Noble B, Wright J, Gorfien J, Heffner R, Spengler RN. Neuronal-associated TNFα: Its role in noradrenergic functioning and modification of its expression following antidepressant administration. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;79:84–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ignatowski TA, Reynolds JL, Sud R, Knight PR, Spengler RN. The dissipation of neuropathic pain paradoxically involves the presence of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:448–460. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ignatowski TA, Spengler RN. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α: presynaptic sensitivity is modified after antidepressant drug administration. Brain Res. 1994;665:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen TS, Baron R, Haanpää M, Kalso E, Loeser JD, Rice ASC, Treede RD. A new definition of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2011;152:2204–2205. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang H, Delong RL, Fisher MH, Juliano RL. Tat-Conjugated PAMAM dendrimers as delivery agents for antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides. J Pharmaceutical Res. 2005;22:2099–2106. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-8330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khabar KSA, Siddiqui S, Armstrong JA. WEHI-13VAR: a stable and sensitive variant of WEHI 164 clone 13 fibrosarcoma for tumor necrosis factor bioassay. Immunol Lett. 1995;46:107–110. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(95)00026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khanna S, Sinclair JG. Noxiuos stimuli produce prolonged changes in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus. Pain. 1989;39:337–343. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90047-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klejbor I, Stachowiak EK, Bharali DJ, Roy I, Spodnik I, Morys J, Bergey EJ, Prasad PN, Stachowiak MK. ORMOSIL nanoparticles as a non-viral gene delivery vector for modeling polyglutamine induced brain pathology. J Neurosci Meth. 2007;165:230–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klur S, Muller C, Pereira de Vasconcelos A, Ballard T, Lopez J, Galani R, Certa U, Cassel J-C. Hippocampal-dependent spatial memory functions might be lateralized in rats: An approach combining gene expression profiling and reversible inactivation. Hippocampus. 2009;19:800–816. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Korhonen T, Karppinen J, Paimela L, Malmivaara A, Lindgren KA, Bowman C, Hammond A, Kirkham B, Jarvinen S, Niinimaki J, Veeger N, Haapea M, Torkki M, Tervonen O, Seitsalo S, Hurri H. The treatment of disc-herniation-induced sciatica with infliximab: one-year follow-up results of FIRST II, a randomized controlled study. Spine. 2006;31:2759–2766. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000245873.23876.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korhonen T, Karppinen J, Paimela L, Malmivaara A, Lindgren KA, Jarvinen S, Niinimaki J, Veeger N, Seitsalo S, Hurri H. Treatment of disc herniation-induced sciatica with infliximab. Spine. 2005;30:2724–728. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000190815.13764.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leung L, Cahill CM. TNF-α and neuropathic pain - a review. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:27–37. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martuscello RT, Spengler RN, Bonoiu AC, Davidson BA, Helinski J, Ding H, Mahajan S, Kumar R, Bergey EJ, Knight PR, Prasad PN, Ignatowski TA. Increasing TNF levels solely in the rat hippocampus produces persistent pain-like symptoms. Pain. 2012;153:1871–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsuzawa-Yanagida K, Narita M, Nakajima M, Kuzumaki N, Niikura K, Nozaki H, Takagi T, Tamai E, Hareyama N, Terada M, Yamazaki M, Suzuki T. Usefulness of antidepressants for improving the neuropathic pain-like state and pain-induced anxiety through actions at different brain sites. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1952–1965. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]