Abstract

Siglecs, sialic acid-recognizing Ig-superfamily lectins, regulate various aspects of immune responses, and have also been shown to induce the endocytosis of binding materials such as anti-Siglec antibodies or sialic acid-harboring bacteria. In this study, we demonstrated that the expression of Siglec-9 enhanced the transfection efficiency of several cell lines such as macrophage RAW264 and non-hematopoietic 293FT cells. We applied this finding to the production of a lentiviral vector in which cells were transfected simultaneously with multiple vectors, and achieved a twice increase in viral production levels. Furthermore, 293FT cells expressing lectin-defective Siglec-9 produced three- to seven-fold higher titer of viral vector compared with parental 293FT cells. These results suggest that Siglec-9 enhanced lentiviral vector production in a lectin-independent manner.

Keywords: Siglec, Transfection efficiency, Lentiviral vector, Viral production

Introduction

Replication-defective retroviral and lentiviral vectors are widely used for the gene manipulation of animal cells. Lentiviral vectors have been used to introduce genes to growth arrested cells, whereas retroviral vectors can only be used for dividing cells. Thus, lentiviral vectors such as the human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1)-based vector are preferentially used. Replication-defective retroviral vectors can be produced by using packaging cells that stably express viral components such as Gag and Pol, and a transgene flanked by viral long terminal repeat (LTR) sequence at both ends. To avoid the production of progeny viruses in target cells, transgenes do not contain genes for viral structural proteins. The LTR sequences are essential for reverse-transcription and integration. A viral vector can be produced by transfecting the env gene alone to packaging cells. The Env protein, which determines the specificity of infection, is often replaced with Env from other viruses to alter the host specificity. The most widely used Env is VSV-G from Vesicular stomatitis virus, which permits the infection of a wide variety of species such as humans, mice, insects, and birds. The plasmid encoding VSV-G is independently transfected to cells because VSV-G is known to be hazardous to cell growth due to the induction of cell fusion.

Although lentiviral vectors have similar characteristics, the procedure for viral preparation differs. Packaging cells cannot be used to prepare HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors because viral Gag and Pol proteins have been shown to have a negative impact on cell growth, and several plasmids that separately encode the transgene, viral gag/pol, and env have to be simultaneously transfected to cells. Thus, the efficiency of viral production is less with the lentiviral system than with the retroviral system in which packaging cells can be used. This results in a low viral titer, limiting the efficiency of gene transfer. In order to increase transfection efficiency, cells originating from human embryonic kidney 293 have been mainly used for virus preparation because of their higher rates of cell growth and transfection.

Sialic acids that cover the cell surface as the terminals of glycosylation were previously demonstrated to play various roles in the regulation of immune responses (Pilatte et al. 1993). Although sialic acids are generally rare in lower organisms, some pathogens possess sialic acids on their surface, which may be in an attempt to evade immune responses by mimicking host cells. Siglecs are sialic acid-recognizing Ig-superfamily lectins prominently expressed on immune cells (Crocker et al. 2012; Varki and Angata 2006). Members of CD33-related Siglecs have been shown to down-regulate both innate and acquired immune responses, and this may occur via cytosolic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) residing in the cytoplasmic region of the protein (Avril et al. 2005; Ikehara et al. 2004; Lajaunias et al. 2005; Nicoll et al. 2003; Paul et al. 2000; Ulyanova et al. 1999; von Gunten et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2007). We previously suggested that CD33-related Siglecs may antagonize Toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated inflammatory responses, leading to a reduction in proinflammatory cytokines and increase in the production of an anti-inflammatory cytokine (Ando et al. 2008). Furthermore, a previous study reported that Siglec-5 and sialoadhesin (Siglec-1) mediated the uptake of Neisseria meningitides, one of the sialic acid-harboring pathogens, into macrophages (Jones et al. 2003). Since these Siglecs are known to be expressed mainly on immune cells, the activity of Siglecs toward non-hematopoietic cells has not yet been elucidated in detail. However, Siglec-F-expressing CHO cells also endocytosed Neisseria meningitides (Tateno et al. 2007), which indicated that Siglecs may modulate the cell function of non-hematopoietic cells. In this study, we examined the effect of Siglecs on the transfection efficiency of cell lines and demonstrated that Siglec-9 enhanced the lentiviral vector production of a non-hematopoietic cell line in a lectin-independent manner that required the transfection of multiple vectors.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The plasmid vector expressing eGFP by a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter was constructed by inserting the eGFP gene into the BamHI/XhoI site of pcDNA4 (Life Technologies–Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and this was designated as pcDNA4/eGFP. The HIV-1-based lentiviral vector plasmid pSicoR which expresses eGFP by CMV promoter (Addgene plasmid 11579) (Ventura et al. 2004) was obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA). The lentiviral vector pLSi/ΔAeGFP expressing eGFP under the control of a chicken actin promoter has been described previously (Motono et al. 2010). pLSi/CMVST6/ΔAeGFP was constructed by inserting the expression cassette of chicken sialyltransferase 6 controlled by a CMV promoter into pLSi/ΔAeGFP. The expression vector of human erythropoietin (hEPO), in which basal expression induced by the truncated ovalbumin promoter was amplified in an automatic feed-forward manner by the TRE sequence and tTA transcription factor, was constructed by inserting the hEPO expression unit in a bicistronic manner by the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) into the MSCV-based vector (Kodama et al. 2012). The vector backbone was changed to pSicoR, which was designated as pLSi/OVA-TRE-hEPO-IRES-tTA/CMVeGFP-W. The expression plasmids for VSV-G (pVSV-G), HIV-1 gag/pol (pLP1), and HIV-1 rev (pLP2) were purchased from Clontech (Mountain View, CA, USA).

Establishment of Siglec-expressing cells and their basic characterization

The RAW264 macrophage cell line was obtained from the Riken BioResource Center (Tsukuba, Japan) and maintained in RPMI1640 (Nissui Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) containing 10 % heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS, PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria), 0.03 % l-glutamine (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan), 5 x 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), 100 U/ml penicillin G (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Wako Pure Chemical Industries). The construction of human Siglec-9-expressing plasmids and the establishment of RAW264 cell lines stably expressing Siglec-9 were described previously (Ando et al. 2008). 293FT cells were purchased from Invitrogen and maintained in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 10 % FCS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), 1 % non-essential amino acids (Gibco Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), 0.03 % l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin G, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Siglec-9RA that has a point mutation converting arginine 120 to alanine for destruction of lectin activity was constructed by PCR and cloned into pcDNA4. Both in Siglec-9 and Siglec-9RA expression plasmids, Siglecs were expressed by a CMV promoter. Each plasmid containing Siglec derivatives was transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies–Invitrogen) and cells surviving in the presence of 20 μg/ml of Zeocine were used as a bulk for subsequent experiments.

The expression of Siglec-9 was confirmed by indirect staining of the anti-Siglec-9 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and FITC-labeled donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Cell proliferation was measured using a cell counting kit (Cell Counting Kit-8; Dojin, Kumamoto, Japan). In brief, the indicated numbers of cells were cultured in a 96-well microtiter plate for 2 days and cells were incubated with WST-8 solution for 4 h followed by the measurement of absorbance at 450 nm.

Evaluation of transfection efficiency and productivity of lentiviral vectors

To examine the transfection efficiency of 293FT cells, pcDNA4/eGFP was transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 and eGFP fluorescence was observed by BioZero (Keyence, Osaka, Japan). Lentiviral vectors were produced by transfecting vectors pLP1 and 2, pVSV-G, and pLSi/CMVST6/ΔAeGFP or pLSi/OVA-TRE-hEPO-IRES-tTA/CMVeGFP-W as reported previously (Motono et al. 2010). The viral titer was determined by infecting Hela cells based on eGFP expression.

Flowcytometric analysis

Transfection efficiency and lentiviral titer were quantified by flowcytometric analysis. Cells were trypsinized after eGFP transfection or lentivirus infection and detached cells were washed in phosphate buffered saline. Flowcytometer (EPICS ALTRA, Beckman-Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) was used to quantify the percentage of eGFP-expressing cells.

Results

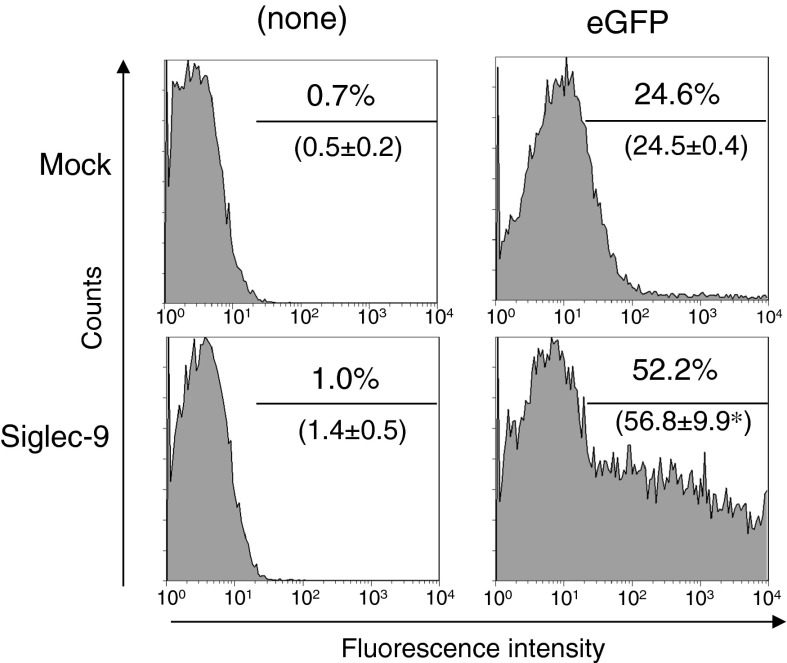

Human Siglec-9 enhanced the transfection efficiency of RAW264 cells

We previously reported that Siglec-9 strongly stimulated the production of IL-10 by RAW264 cells, a mouse macrophage-like cell line, when these cells were stimulated with various TLR ligands (Ando et al. 2008). Since this enhancement was also associated with higher expression of IL-10 mRNA, we applied the typical luciferase assay to examine the underlying mechanisms. Renilla luciferase expression regulated by the ubiquitous thymidine kinase promoter was strongly enhanced in Siglec-9-expressing RAW264 cells compared with control RAW264 cells (data not shown). When pSicoR was transfected, approximately 24.5 ± 0.4 % of cells showed eGFP fluorescence (Fig. 1). This was consistent with the observation that DNA uptake by RAW264 cells was low. On the other hand, 56.8 ± 9.9 % of Siglec-9-expressing RAW264 expressed eGFP; approximately two times higher than that of control cells (Fig. 1). These results suggest that the expression of human Siglec-9 strongly enhanced the transfection efficiency of RAW264 cells.

Fig. 1.

Siglec-9 enhanced the transfection efficiency of RAW264 cells. RAW264 cells containing either control vector (Mock) or Siglec-9-expressing vector (Siglec-9) (Ando et al. 2008) were transfected with the eGFP expression vector (pSicoR) and cultured for 2 days, and eGFP expression was analyzed by flowcytometry. One of the three independent experiments with similar results is shown. Numbers in parenthesis show mean value with standard deviation. *p < 0.05 versus mock cells by the Student’s t test

Establishment of 293FT cells expressing Siglec-9

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells are widely used in basic research. 293FT cells, a derivative of 293 cells, express the SV40 large T antigen and are often used in the production of lentiviral vectors. To examine the effect of Siglecs on non-hematopoietic cells, 293FT cells were transfected with the Siglec-9-expression vector and cells harboring the vector were concentrated using the plasmid-encoded Zeocin-resistant phenotype. Cells from bulk culture were used in following experiments to avoid chromosomal position effects on Siglec-9 expression. After transfecting Siglec-9-expressing vectors and Zeocin selection, the expression of Siglec-9 on the cell surface was confirmed using flow cytometry (Fig. 2a). The expression levels of Siglec-9 were higher in 293FT cells than in RAW264 cells (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Establishment of Siglec-9-expressing 293FT cells. a Confirmation of the expression of Siglec-9 and Siglec-9RA by flow cytometric analysis. Cells were indirectly stained by the anti-Siglec-9 antibody. Dotted line, control IgG; Solid line, anti-Siglec-9 antibody. b Confirmation of the lack of sialic acid-binding in the RA mutant of Siglec-9. Transiently transfected 293FT cells were examined for binding with either mock-treated (none) or sialidase-treated chicken erythrocytes. Bound erythrocytes after a mild wash were shown by white arrows. Bar 20 μm. c Growth of Siglec-9-expressing cells. Cells were cultured for 2 days and the cell number was estimated by WST-8. Data are expressed as mean value with standard deviation of triplicate culture. One of the two independent experiments with similar results is shown. d, e Transfection efficiency of Siglec-9-expressing 293FT cells. A suboptimal dose of the eGFP expression vector was transfected. pcDNA4/eGFP vector (0.08 μg) and pcDNA4 empty vector (0.72 μg) were cotransfected into 293FT cells in 24-well plate and cells were cultured for 2 days. Microscopic images (d) and the percentage of eGFP-expressing cells (e) are shown. Bar 100 μm. Data are expressed as mean value with standard deviation of four independent experiments. *p < 0.05 versus parental cells by the Student’s t test

Siglecs have been shown to mediate the uptake of several pathogens by macrophages through an interaction with sialic acids on pathogens. To determine whether lectin activity was required for enhanced transfection efficiency, a lectin mutant was established. Since a positive charge on the Arg residue in the lectin domain of Siglecs is required for sialic acid binding, Arg120 was replaced with Ala. We confirmed that the point mutation of Siglec-9 (Siglec-9RA) diminished the sialic acid-dependent binding of chicken erythrocytes to Siglec-9RA-expressing 293FT cells (Fig. 2b). The expression levels of Siglec-9RA in 293FT were higher than those of Siglec-9 (Fig. 2a). Western blotting confirmed the expression of Siglec-9 and Siglec-9RA and also the higher expression of Siglec-9RA (data not shown).

The growth of Siglec-expressing cells was examined prior to the transfection experiments. WST-8, an indicator of mitochondria activity and the cell proliferation, was added after 2 days and the mitochondrial activities of these cells were then compared. The level of cell proliferation was similar between mock and Siglec-9RA-expressing cells, while Siglec-9-expressing cells grew at a slower rate (Fig. 2c).

Transfection efficiency is known to be high in 293FT cells. Thus, we reasonably assumed that Siglec did not have a marked influence on transfection efficiency. In fact, more than 80 % of cells expressed eGFP when 0.8 μg of pcDNA4/eGFP was transfected to control cells as recommended by supplier (data not shown). In the suboptimal transfection condition, in which a reduced amount of plasmid was used (10 % that of the normal condition), Siglec-9 moderately enhanced transfection efficiency in 293FT cells (Fig. 2d, e), which indicated that Siglec-9 potentially enhanced the transfection efficiency of 293FT cells. Transfection efficiency was also enhanced in Siglec-9RA-expressing cells, demonstrating that this enhancing activity did not require the lectin activity of Siglec-9.

Siglec-9 enhanced lentiviral vector production by 293FT cells

Since a significant difference was not observed in transfection efficiency in a simple transfection experiment, the production of lentiviral vectors was examined, because the transfection efficiency of multiple plasmids limited viral vector production. Lentiviral vector production commonly requires the simultaneous co-transfection of four different plasmids to minimize the appearance of hazardous replication-competent viruses. Indispensable components were divided into 4 separate plasmids: plasmid pLP1 expressing the viral structural proteins Gag/Pol, pLP2 expressing Rev, which enables the effective export of genomic virus RNA, pVSV-G encoding the envelope protein, and the lentiviral vector containing a gene of interest flanked with partially deleted LTR at both ends.

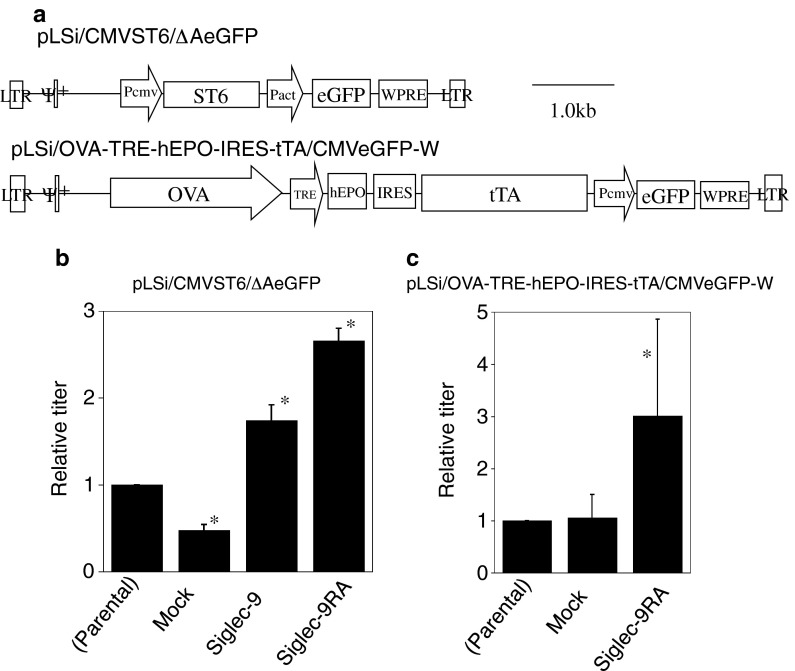

The vector constructs used are shown in Fig. 3a. We used two vectors: the lengths between LTRs were 6.3 kb for pLSi/CMVST6/ΔAeGFP and 9.9 kb for pLSi/OVA-TRE-hEPO-IRES-tTA/CMVeGFP-W. We firstly transfected the viral vector (pLSi/CMVST6/ΔAeGFP) to Siglec-expressing cells together with pLP1, pLP2 and pVSV-G. As shown in Fig. 3b, the viral titer increased in Siglec-9-expressing cells, which may have been due to enhanced transfection efficiency. Furthermore, Siglec-9RA cells achieved better results. The difference in expression level may explain the difference observed in efficiencies of viral production. However, we cannot deny that the reduced growth rate directly affected viral production. Since Siglec-9RA achieved better results, we used this cell line for further analyses. Using a longer vector construct (pLSi/OVA-TRE-hEPO-IRES-tTA/CMVeGFP-W), high titers could be obtained with Siglec-9RA-expressing cells (Fig. 3c). The titer in some experiments was slightly lower in mock cells than in parental 293FT cells. The CMV promoter was used for mock- and Siglec-expression vectors, which may have interfered with the production of viral proteins that are also expressed under the CMV promoter. We then repeated a similar transfection experiment under suboptimal conditions in which the cell number was decreased to half in order to obtain a pure viral vector preparation with a reduction in the amount of cell debris. The reduction enables repeated concentration procedures, to obtain high titer of viral vectors. Under this condition, we could obtain seven times higher viral titer with Siglec-9RA cells (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Siglec-9 enhanced lentiviral vector production by 293FT cells. a Schematic representation of the lentiviral vector. The provirus form is indicated. b, c Production of the lentiviral vector using Siglec-9- and Siglec-9RA-expressing 293FT cells. Lentiviral vector plasmid (0.38 μg), pLP1 (0.2 μg), pLP2 (0.11 μg) and pVSV-G (0.11 μg) were cotransfected to 293FT cells in 24-well plate (2 × 105/well) and the culture medium was changed after 24 h. Culture supernatants containing viral vector were harvested after additional 48 h culture, and the titer was determined after 2 days using Hela cells. The relative titer is shown. LTR, deleted LTR; ψ+, virus packaging signal sequence; Pcmv, CMV promoter; ST6, chicken sialyltransferase 6; Pact, chicken β-actin promoter; WPRE, woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element; OVA, chicken ovalbumin promoter (−3,861 to −1,569 bp, Kodama et al. 2012). Data are expressed as mean value with standard deviation of five (b) or three (c) independent experiments. *p < 0.05 versus parental cells by the Student’s t test

Fig. 4.

Siglec-9RA enhanced lentiviral vector production by 293FT cells under suboptimal conditions. 293FT cells (1 × 105/well, half number of optimum condition in Fig. 3) were transfected with the same amounts of plasmids shown in Fig. 3, and viral titer was determined after 2-day culture. Data are expressed as mean value with standard deviation of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 versus parental cells by the Student’s t test

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that the expression of Siglec-9 enhanced transfection efficiency. Although the expression of endogenous Siglecs is typically restricted to hematopoietic cells, this enhancing activity was also observed for non-hematopoietic cells such as 293FT. An enhancement of transfection efficiency in 293FT enables the production of higher titers of lentiviral vectors. The preparation of very high titers of viral vectors more than 108 transduction unit (TU)/ml is a prerequisite when establishing transgenic animals such as the chicken. Usually, titer of viral preparation was <106 and concentrated preparation (108 TU/ml) could be obtained by repeated centrifugation. Thus, seven-fold increases in viral titers have a marked effect on transgenesis.

The molecular basis to increase DNA delivery in Siglec cells has not yet been clarified. In general, molecules that mediate endocytosis enhance transfection efficiency. Several studies reported that EGF-modified lipid vesicles were constructed for effective delivery to tumor cells expressing high levels of the EGF receptor (Kikuchi et al. 1996). A similar approach has been used for transferrin or lactoferrin with their receptors, and the RGD peptide with integrins (Cheng 1996; Elfinger et al. 2007; Kunath et al. 2003; Rao et al. 2008; Scott et al. 2001). In this regard, Siglecs also exhibited enhanced efficiency of uptake of binding substances. In addition to sialic acid-containing bacteria, the antibody toward CD33 (Siglec-3) was effectively endocytosed into leukemia cells, and has been used for immunotoxin therapy (van der Velden et al. 2001). These results implicate Siglecs in the uptake of their binding molecules. However, cationic liposomes do not appear to bind with Siglec as a sialic acid mimetic. Consistent with this notion, Siglec-9RA exhibited an enhanced activity. Whether cationic liposomes interact with Siglec-9 in a lectin-independent manner has not yet been established.

Siglec expression may indirectly affect transfection efficiency. For example, the density of GM1-enriched lipid rafts was inversely correlated with efficiency (Kovacs et al. 2009). Siglec-9 was shown to localize to lipid rafts (our unpublished observations), which implied that Siglec-9 may affect the dynamics of the cell membrane such as lipid rafts; however, this localization was not observed for Siglec-9RA (Ando et al. unpublished result).

The endocytosis of Siglec-F was previously shown to require both ITIM and ITIM-like motifs (Tateno et al. 2007). On the other hand, the requirement of these motifs for CD33 endocytosis is somewhat controversial (Orr et al. 2007; Walter et al. 2008). Our preliminarily results showed that these motifs were required to enhance transfection efficiency, which indicated the need for cellular signaling through the ITIMs of Siglec-9 to achieve this enhancement. In the present study, we used Siglec-9RA-expressing bulk cells. If a cell line expressing Siglec-9RA in a higher level will be available, it may give higher titer of viral vector. Further characterization including isolation of the cell lines and optimization of the expression level of Siglec-9RA may lead to the production of higher titer lentiviral and retroviral vectors.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the Takeda Foundation, Mishima Foundation, and Terumo Foundation.

References

- Ando M, Tu W, Nishijima K, Iijima S. Siglec-9 enhances IL-10 production in macrophages via tyrosine-based motifs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369(3):878–883. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avril T, Freeman SD, Attrill H, Clarke RG, Crocker PR. Siglec-5 (CD170) can mediate inhibitory signaling in the absence of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(20):19843–19851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng PW. Receptor ligand-facilitated gene transfer: enhancement of liposome-mediated gene transfer and expression by transferrin. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7(3):275–282. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.3-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker PR, McMillan SJ, Richards HE. CD33-related siglecs as potential modulators of inflammatory responses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1253:102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfinger M, Maucksch C, Rudolph C. Characterization of lactoferrin as a targeting ligand for nonviral gene delivery to airway epithelial cells. Biomaterials. 2007;28(23):3448–3455. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikehara Y, Ikehara SK, Paulson JC. Negative regulation of T cell receptor signaling by Siglec-7 (p70/AIRM) and Siglec-9. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43117–43125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403538200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C, Virji M, Crocker PR. Recognition of sialylated meningococcal lipopolysaccharide by siglecs expressed on myeloid cells leads to enhanced bacterial uptake. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1213–1225. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi A, Sugaya S, Ueda H, Tanaka K, Aramaki Y, Hara T, Arima H, Tsuchiya S, Fuwa T. Efficient gene transfer to EGF receptor overexpressing cancer cells by means of EGF-labeled cationic liposomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:666–671. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama D, Nishimiya D, Nishijima K, Okino Y, Inayoshi Y, Kojima Y, Ono K, Motono M, Miyake K, Kawabe Y, Kyogoku K, Yamashita T, Kamihira M, Iijima S. Chicken oviduct-specific expression of transgene by a hybrid ovalbumin enhancer and the tet expression system. J Biosci Bioeng. 2012;113:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs T, Karasz A, Szollosi J, Nagy P. The density of GM1-enriched lipid rafts correlates inversely with the efficiency of transfection mediated by cationic liposomes. Cytometry A. 2009;75:650–657. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunath K, Merdan T, Hegener O, Haberlein H, Kissel T. Integrin targeting using RGD-PEI conjugates for in vitro gene transfer. J Gene Med. 2003;5:588–599. doi: 10.1002/jgm.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajaunias F, Dayer JM, Chizzolini C. Constitutive repressor activity of CD33 on human monocytes requires sialic acid recognition and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-mediated intracellular signaling. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:243–251. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motono M, Yamada Y, Hattori Y, Nakagawa R, Nishijima K, Iijima S. Production of transgenic chickens from purified primordial germ cells infected with a lentiviral vector. J Biosci Bioeng. 2010;109:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll G, Avril T, Lock K, Furukawa K, Bovin N, Crocker PR. Ganglioside GD3 expression on target cells can modulate NK cell cytotoxicity via siglec-7-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1642–1648. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr SJ, Morgan NM, Elliott J, Burrows JF, Scott CJ, McVicar DW, Johnston JA. CD33 responses are blocked by SOCS3 through accelerated proteasomal-mediated turnover. Blood. 2007;109:1061–1068. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul SP, Taylor LS, Stansbury EK, McVicar DW. Myeloid specific human CD33 is an inhibitory receptor with differential ITIM function in recruiting the phosphatases SHP-1 and SHP-2. Blood. 2000;96:483–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilatte Y, Bignon J, Lambré CR. Sialic acids as important molecules in the regulation of the immune system: pathophysiological implications of sialidases in immunity. Glycobiology. 1993;3:201–218. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.3.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao GA, Tsai R, Roura D, Hughes JA. Evaluation of the transfection property of a peptide ligand for the fibroblast growth factor receptor as part of PEGylated polyethylenimine polyplex. J Drug Target. 2008;16:79–89. doi: 10.1080/10611860701733328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott ES, Wiseman JW, Evans MJ, Colledge WH. Enhanced gene delivery to human airway epithelial cells using an integrin-targeting lipoplex. J Gene Med. 2001;3:125–134. doi: 10.1002/jgm.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateno H, Li HY, Schur MJ, Bovin N, Crocker PR, Wakarchuk WW, Paulson JC. Distinct endocytic mechanisms of CD22 (Siglec-2) and Siglec-F reflect roles in cell signaling and innate immunity. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5699–5710. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00383-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulyanova T, Blasioli J, Woodford-Thomas TA, Thomas ML. The sialoadhesin CD33 is a myeloid-specific inhibitory receptor. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3440–3449. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199911)29:11<3440::AID-IMMU3440>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Velden VH, te Marvelde JG, Hoogeveen PG, Bernstein ID, Houtsmuller AB, Berger MS, van Dongen JJ. Targeting of the CD33-calicheamicin immunoconjugate Mylotarg (CMA-676) in acute myeloid leukemia: in vivo and in vitro saturation and internalization by leukemic and normal myeloid cells. Blood. 2001;97:3197–3204. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.10.3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki A, Angata T. Siglecs—the major subfamily of I-type lectins. Glycobiology. 2006;16:1R–27R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A, Meissner A, Dillon CP, McManus M, Sharp PA, Van Parijs L, Jaenisch R, Jacks T. Cre-lox-regulated conditional RNA interference from transgenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(28):10380–10385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403954101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gunten S, Yousefi S, Seitz M, Jakob SM, Schaffner T, Seger R, Takala J, Villiger PM, Simon HU. Siglec-9 transduces apoptotic and nonapoptotic death signals into neutrophils depending on the proinflammatory cytokine environment. Blood. 2005;106(4):1423–1431. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter RB, Raden BW, Zeng R, Hausermann P, Bernstein ID, Cooper JA. ITIM-dependent endocytosis of CD33-related Siglecs: role of intracellular domain, tyrosine phosphorylation, and the tyrosine phosphatases, Shp1 and Shp2. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83(1):200–211. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Angata T, Cho JY, Miller M, Broide DH, Varki A. Defining the in vivo function of Siglec-F, a CD33-related Siglec expressed on mouse eosinophils. Blood. 2007;109(10):4280–4287. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]