Abstract

Aiming to establish a method for the noninvasive discrimination of cancer cells from normal cells in adherent culture, we investigated to employ all phase shift data for all pixels inside a cell. The bird’s-eye views of phase shifts of human prostate epithelial cells (PRECs) and human prostatic carcinoma epithelial cell (PC-3) lines acquired by phase-shifting laser microscopy showed tableland and cone shapes, respectively, while treatment of PRECs with cytochalasin D resulted in the cone shape. So, the profile of phase shift in both sections towards the x- and y-axes of the views through the peaks of the phase shifts in PRECs and PC-3 cells were trapezoid-like and triangle-like, respectively. Typical profiles of phase shifts in a section in PRECs or PC-3 cells were calculated by averaging from 10 cells and smoothing. Cancer index is defined as the deduction of sums of the squared difference between a real cell and the typical profiles for a PREC and a PC-3 cell. The cancer indices for PC-3 and hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines were positive, while those for PRECs and human normal cryopreserved hepatocytes were negative. Cancer indices along the major axis of fibroblast-like cells of normal mesenchymal stem cells and the osteosarcoma cell line were negative and positive, respectively. Consequently, several cancer cells could be noninvasively discriminated from normal cells by calculating the cancer index employing phase shift for all pixels inside the cells.

Keywords: Cancer cells, Phase shift, Noninvasive, Discrimination

Introduction

Cells should be evaluated before transplantation from the viewpoints of quality and process controls because the populations of cells cultivated for transplantation in regenerative medicine are generally heterogeneous. Most transplantations require autologous cells and a minimum number of cells to be cultivated. Thus, cells could not be discarded for quality evaluation. Consequently, cell quality should be monitored nondestructively and noninvasively.

Besides a two-dimensional cell morphology analysis for the noninvasive estimation of such as the degree of differentiation from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to chondrocytes (Takagi et al. 2008), a noninvasive measurement of the three-dimensional morphology of adherent animal cells by phase-shifting laser microscopy (PLM) was developed (Endo et al. 2002). Two neighboring fields of view in PLM, with cells and without cells, were selected as the sample and reference fields, respectively. Two laser light beam passing through the sample and reference fields were overlapped by a biprism and show the hologram on CCD. Analyzing the hologram, and the phase shift (ΔΦ) between the sample and reference fields was determined for all pixels in the sample field (Takagi et al. 2007). We previously reported that the phase shift in adherent animal cells, which is the product of cell height and cell refractive index, as shown in Eq. 1, could be noninvasively determined in a short time by PLM.

| 1 |

where ΔΦ is the measured phase shift (rad), λ0 is the laser wavelength (λ0 = 632.8 nm), n1 and n0 are the refractive indices of cells and medium, respectively, and dc is the height of cells (Takagi et al. 2007).

Because it is important to determine whether cultured cells include cancer cells, a noninvasive evaluation method to determine whether cancer cells are present is necessary. There is no apparent difference in morphology between normal and carcinoma cells, e.g., the human prostatic carcinoma epithelial cell (PC-3) line and human prostate epithelial cell (PREC), human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines (Hep3B, PLC, HLF, and Huh7), and human cryopreserved hepatocytes (HCHs). However, the PC-3 and human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines show markedly lower phase shifts, as measured by PLM, than PRECs and HCHs (Tokumitsu et al. 2010). It was also reported that the smaller height of PC-3 cells caused by a lower actin content than of PREC might be the reason for the lower phase shift in PC-3 cells (Takagi and Tokunaga 2013). Consequently, we proposed the noninvasive discrimination of cancer cells from normal cells by measuring phase shift by PLM. However, the sensitivity and specificity should be improved, because the histograms of phase shifts in normal and cancer cells overlapped.

MSCs in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle could be noninvasively discriminated on the basis of their higher phase shift measured by PLM (Tokumitsu et al. 2009, Ito and Takagi 2008), which is derived from the changes in refractive index due to DNA aggregation and cell height in the G2/M cell cycle phase (Sanger and Sanger 1980). Time-lapse analysis of phase shift using PLM revealed that the laser phase shifts in PRECs and PC-3 cells in the mitotic phase were markedly higher than those in the interphase. The phase shift in PC-3 cells in the interphase was markedly lower than that in PRECs throughout the cell cycle. Therefore, it was proposed that adherent PC-3 cancer cells could be noninvasively discriminated with high sensitivity and specificity from normal adherent PRECs by the periodical measurement of phase shift during culture using PLM (Takagi and Shibaki 2012). However, periodical measurement of phase shift in many cells requires a long time, and it is desired to discriminate cancer cells precisely and noninvasively by one-time measurement of the phase shift in each cell.

Although many phase shift data for many pixels in a cell were available, only the highest phase shift in a cell was employed in those previous studies mentioned above (Tokumitsu et al. 2010; Takagi and Tokunaga 2013; Takagi and Shibaki 2012).

Consequently, in this study, we investigated the noninvasive discrimination of cancer cells from normal cells using phase shift data for all pixels in a cell acquired by one-time measurement by PLM.

Materials and methods

Cells

Primary normal human prostate epithelial cells (PRECs), a human prostatic carcinoma epithelial cell line (PC-3), human cryopreserved hepatocytes (HCHs), two kinds of human hepatocellular carcinoma cell [Hep3B (ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) HB8064 (Takagi et al. 1997)), HLF (JCRB405 (JCRB Cell Bank, Osaka, Japan) (Takagi et al. 1997, Doi et al. 1975))], mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and an osteosarcoma cell line (HuO-3N1, RIKEN (Wako, Japan) RCB2104) were used. PRECs and PC-3 cells were purchased from the Applied Cell Biology Research Institute (ACBRI, Kirkland, WA, USA). HCHs were purchased from BD Bioscience (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). MSCs were isolated from bone marrow aspirates obtained by routine iliac crest aspiration from human donors, as previously reported (Takagi et al. 2003). All the subjects enrolled in this study gave their informed consent. This study was approved by our institutional committee on human research, as required by the study protocol.

Media

Ham’s F-12 K medium (Dainippon Seiyaku Company, Osaka, Japan) and a mixture (1:1) of DMEM and F12 (Gibco) supplemented with 10 % FBS, streptomycin (0.1 mg/L), and penicillin (100 U/L) were used for the culture of PC-3 cells and PRECs, respectively. Hepatocyte basal medium (CAMBREX, Charles City, IA, USA) supplemented with bovine serum albumin (fatty-acid-free), transferrin, hydrocortisone, ascorbic acid, recombinant human epidermal growth factor, insulin, and gentamycin/amphotericin B (GA-1000, CAMBREX) were used for the culture of HCHs. DMEM (Gibco, Paisley, U.K.) supplemented with 10 % FBS, streptomycin (0.1 mg/L), and penicillin (100 U/L) were used for the culture of Hep3B cells, HLF cells, MSCs, and HuO-3N1 cells.

Cultivation

The cells were plated on a dish with grids (11.8 cm2; SARSTEDT, Nümbrecht, Germany) at a density of 0.15 × 104 cells/cm2 in their respective media and incubated at 37 °C in 5 % CO2 atmosphere for 72 h. In some cases, the culture supernatant was removed after 72 h of cultivation, and cells were incubated with medium containing 20 μM cytochalasin D (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 3 h. All the culture experiments were performed twice and the same tendencies were confirmed.

Phase shift analysis using PLM

The cells attached to the bottom surface of the culture dish were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde and observed by PLM (FK Optical Laboratory, Saitama, Japan). The phase shift (Δφ) was determined for all the pixels in the sample field by PLM. All phase shift data were stored in an Excel file and plotted in the x–y plane of the bird’s-eye view. The section towards the x- and y-axes of the bird’s-eye view through the point at which the phase shift was highest in a cell was drawn employing normalized cell length (LN) and phase shift (ΔφN). In the case of fibroblast-like cells (MSCs and HuO-3N1 cells), the section towards the major and minor axes of cell shape was drawn.

Calculation of cancer index

The typical profile of phase shift in a cell, whose axes were normalized cell length (LN) and normalized phase shift (ΔφN), was set for PRECs and PC-3 cells by averaging from 10 cells and smoothing. Cancer index is defined as the deduction of sums of the squared difference between an unknown real cell and the respective typical profile of a PREC or a PC-3 cell, as shown in Eq. 2.

| 2 |

where ΔφN, ΔφN(Normal), ΔφN(Cancer), and NL are the normalized phase shift in an unknown cell, the normalized phase shift in the typical profile of PREC, the normalized phase shift in the typical profile of PC-3 at each measurement point on an axis, and the number of measurement points for phase shift on an axis in a cell, respectively.

Results

Comparison of bird’s-eye views of phase shifts in PRECs and PC-3 cells

The bird’s-eye views of phase shift acquired by PLM of PRECs and PC-3 cells showed tableland and cone shapes, respectively (Fig. 1a, c). The PLM observation of PRECs after the treatment with cytochalasin D showed a cone-shape view (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Bird’s-eye views of phase shifts in PREC and PC-3 cell. The bird’s-eye views of phase shifts were acquired by PLM of an adhesive PREC (a) and a PC-3 cell (c) without cytochalasin D treatment and of a PREC with the treatment (b), respectively. X and Y are the axes of the observation view field

Distribution of phase shift in the section of PRECs and PC-3 cells

The sections towards the x- and y-axes of the bird’s-eye view through the peak of the phase shift in PRECs and PC-3 cells were made by plotting the phase shift against x- or y-axis. After plotting, the phase shift, the x and y values were normalized to ΔφN and LN, respectively, for each cell (Fig. 2). Both sections towards the x- and y-axes for PRECs appeared trapezoid-like, while those for PC-3 cells appeared triangle-like.

Fig. 2.

Sections of bird’s-eye views of phase shifts in PREC and PC-3 cell. The sections of the bird’s-eye views of phase shifts in a PREC and a PC-3 cell towards x- [PREC (X), PC-3 (X)] and y-axes [PREC (Y), PC-3 (Y)] through the peaks of phase shifts are shown after the normalization of phase shift, x, and y values. LN, normalized length; ΔφN, normalized phase shift

Discrimination of PC-3 cells from PREC by cancer index

The average ΔφN was calculated for each LN and smoothened to obtain the typical profiles for PRECs and PC-3 cells using 20-section data similar to those shown in Fig. 2 (sections towards the x- and y-axes for 10 cells; Fig. 3). Cancer index was calculated for PRECs and PC-3 cells (n = 10) other than those employed to set the typical profiles of the cells shown in Fig. 3. All the phase shift profiles in both the x- and y-axes for PRECs showed a negative cancer index, while those for PC-3 cells showed a positive cancer index (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Typical profiles of phase shifts in normal PREC and cancer PC-3 cell. The average ΔφN was calculated for each LN and smoothened to obtain the typical profiles for PRECs and PC-3 cells using 20-section data similar to those shown in Fig. 2 (sections towards the x- and y-axes for 10 cells). LN, normalized length; ΔφN, normalized phase shift

Fig. 4.

Comparison of cancer index between PRECs and PC-3 cells. Cancer index was calculated for PRECs and PC-3 cells towards x- (X) and y- (Y) axes using the respective typical profiles of the cells shown in Fig. 3 (n = 10)

Discrimination of hepatocellular carcinoma cells based on cancer index

The bird’s-eye views of the phase shifts of HCHs and human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines (Hep3B and HLF) acquired by PLM showed tableland and cone shapes, respectively (data not shown). Both sections towards the x and y axis for HCHs appeared trapezoid-like, while those for Hep 3B cells were triangle-like (Fig. 5). Cancer index was calculated for 10 cells each of HCHs, Hep 3B cells, and HLF cells using the typical profiles shown in Fig. 3. All the phase shift profiles in both the x and y axis for HCHs showed a negative cancer index, while those for Hep 3B and HLF cells showed positive cancer index (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Sections of phase shifts in PRECs and PC-3 cells. The sections of the bird’s-eye views of phase shifts in HCHs and Hep 3B cells towards x- [HCH (X), Hep 3B (X)] and y- [HCH (Y), Hep 3B (Y)] axes through the peaks of phase shifts are shown after the normalization of phase shift, x, and y values. LN, normalized length; ΔφN, normalized phase shift

Fig. 6.

Comparison of cancer index between HCHs and hepatocarcinoma cells. Cancer index was calculated for HCHs, Hep 3B cells, and HLF cells towards the x- (X) and y- (Y) axes using the respective typical profiles of normal PRECs and cancer PC-3 cells shown in Fig. 3. (n = 10)

Discrimination of fibroblast-like shaped cancer cell based on cancer index

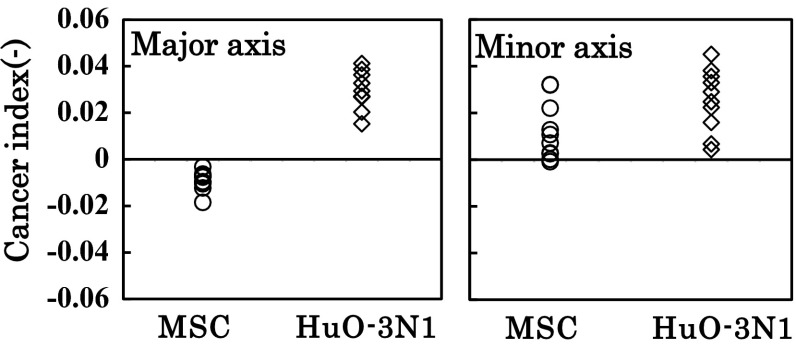

Sections towards the major and minor axes for adherent fibroblast-like MSCs and the osteosarcoma cell line (HuO-3N1) were made, respectively (Fig. 7). The sections towards the major axis for MSCs and HuO-3N1 cells appeared trapezoid- and triangle-like, respectively, while the sections towards the minor axis for both cell types appeared triangle-like (Fig. 7). Cancer index was calculated for MSCs and HuO-3N1 cells (n = 10) using the typical profiles shown in Fig. 3. The cancer indices for MSCs and HuO-3N1 cells in the minor axis were positive (Fig. 8). However, all the phase shift profiles in the major axis for MSCs showed a negative cancer index, while those for HuO-3N1 cells showed a positive cancer index (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Sections of phase shifts in MSCs and HuO-3N1 cells. The sections of the bird’s-eye views of phase shifts in MSCs and HuO-3N1 cells towards the major [MSC (Major axis), HuO-3N1 (Major axis)] and minor [MSC (Minor axis), HuO-3N1 (Minor axis)] axes through the peaks of phase shifts are shown after the normalization of phase shift, major axis, and minor axis values. LN, normalized length; ΔφN, normalized phase shift

Fig. 8.

Comparison of cancer index between MSCs and HuO-3N1 cells. Cancer index was calculated for MSCs and HuO-3N1 cells towards the major (Major axis) and minor (Minor axis) axes using the respective typical profiles of normal PRECs and cancer PC-3 cells shown in Fig. 3 (n = 10)

Discussion

The bird’s-eye views of phase shift of adhesive human PRECs and PC-3 cells acquired by PLM showed tableland and cone shapes, respectively (Fig. 1a, c). It was reported that the difference in phase shift between PRECs and PC-3 cells is due to the difference in actin density between them (Takagi and Tokunaga 2013). Namely, actin content in PREC was markedly larger than that of PC-3, while phase difference in both cells were comparable in G2/M cell cycle phase. The phase difference was proportional to actin content. Moreover, the degradation of actin in PRECs by cytochalasin D resulted in the change from the tableland shape to the cone shape (Fig. 1b). Thus, the tableland and cone shapes might be the characteristic features of normal and cancer cells, respectively.

If the summit of the cone shape shows the nucleus, the overlay indication of phase shift with phase contrast may indicate the location of nucleus.

The sections towards the x and y axis of the bird’s-eye views through the peaks of the phase shifts in normal (PRECs and HCHs) and cancer (PC-3 and Hep 3B cells) cells appeared trapezoid-like and triangle-like, repectively (Figs. 2, 5), which might be due to the tableland- and cone-shaped bird’s-eye views of the phase shifts. Consequently, trapezoid- and triangle-like sections might be the characteristic features of normal and cancer cells, respectively.

Based on the above findings, it is supposed that cancer cells could be discriminated from normal cells by discriminating triangle-like cells from trapezoid-like cells. Typical profiles of the phase shifts in normal and cancer cells were set by averaging and smoothing the phase shifts sections towards the x- and y-axes for PRECs and PC-3 cells (Fig. 3), and cancer index was calculated for normal (PRECs and HCHs) and cancer (PC-3 and Hep 3B cells) cells, respectively. The cancer indices for the normal (PRECs and HCHs) and cancer (PC-3 and Hep 3B cells) cells were negative and positive, respectively (Figs. 4, 6). Thus, the discrimination of epithelial-like cancer cells from epithelial-like normal cells is possible by comparing the phase shift profile of unknown cells with the typical profiles of PRECs and PC-3 cells.

On the other hand, fibroblast-like cells showed section shapes which were different (trapezoid-like and triangle-like) between normal (MSCs) and cancer (HuO-3N1 cells) cells only in the direction of the major axis, and both sections were triangle-like in the direction of the minor axis (Fig. 7). Consequently, the discrimination of fibroblast-like cancer cells (HuO-3N1 cells) from fibroblast-like normal cell (MSCs) based on the cancer index was possible only in the direction of the major axis (Fig. 8).

The phase shift is the product of cell height and the difference in refractive index between the cell and the medium (Takagi et al. 2007). Because the nucleus, which is the largest organelle, is generally located at the center of a cell, the height at the center of a cell may be largest. The refractive index of the nucleus is larger than that of the cytoplasm (Takagi et al. 2007). Thus, the peak of the phase shift in a cell may be located at the center area of the cell.

The phase shift at the outer edge of a cell was almost zero and the phase shift monotonically decreased from the center to the edge of a cell (Figs. 1, 5, and 7). The slope of the decrease was almost straight for epithelial-like cancer cells (Figs. 1, 5). In contrast, the large phase shift was maintained in an area near the center, and the outer area showed a rapid decrease in the phase shift in epithelial-like normal cells (Figs. 1, 5). It is supposed that a high actin density in a normal cell supports a large cell height around the central area of a cell, which resulted in the plateau (trapezoid) of the phase shift in this area.

This phenomenon may also be realized in the major axis direction of fibroblast-like cells (MSCs and HuO-3N1 cells) and resulted in the trapezoid- and triangle-like sections, respectively. However, it may be difficult for actin to support the cell height in the minor axis direction, because actin fibers generally elongate along the direction of the major axis in a fibroblast-like cell. This may be one of the reasons why there is no apparent difference in the shape of the section in the direction of the minor axis between fibroblast-like normal cells (MSCs) and cancer cells (HuO-3N1 cells) (Fig. 7).

The protocol for the discrimination of cancer cells from normal cells by determining the phase shift by PLM is proposed as follows. If the circularity is large as in the case of an epithelial-like cell, cancer index was calculated in the direction of either x- or y-axis. If the circularity is small as in the case of a fibroblast-like cell, cancer index was calculated in the direction of the major axis. In both cases, the cells with a positive cancer index should be discriminated as cancer cells.

To detect the contamination of cancer cells among normal cells, many cells should be analyzed in one dish. For example, if the percentage of the contamination is 0.1 % and one view field of PLM observation contains 5 cells, at least 1000 cells in 200 view field should be analyzed and it may take approximately 100 min because the determination of phase shift of all pixels in one view field takes 30 s.

Conclusions

Thus, cancer cells including fibroblast-like cancer cells could be noninvasively discriminated from normal cells by calculating cancer index by one-time measurement of phase shift for all pixels in a cell.

References

- Doi I, Namba M, Sato J. Establishment and some biological characteristics of human hepatoma cell lines. Gann. 1975;66:385–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo J, Chen J, Kobayashi D, Wada Y, Fujita H. Transmission laser microscope using the phase-shifting technique and its application to measurement of optical waveguides. Appl Opt. 2002;41:1308–1314. doi: 10.1364/AO.41.001308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Takagi M. Correlation between cell cycle phase of adherent Chinese hamster ovary cells and laser phase shift determined by phase-shifting laser microscopy. Biotechnol Lett. 2008;31:39–42. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9839-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger JW, Sanger JM. Surface and shape changes during cell division. Cell Tissue Res. 1980;209:177–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00237624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M, Shibaki Y. Time-lapse analysis of laser phase shift for noninvasive discrimination of human normal cells and malignant tumor cells. J Biosci Bioeng. 2012;114:556–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M, Tokunaga N. Correlation between actin content and phase-shift of adhesive normal and malignant prostate epithelial cells. J Biosci Bioeng. 2013;115:310–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M, Fukuda N, Yoshida T. Comparison of different hepatocyte cell lines for use in a hybrid artificial liver model. Cytotechnology. 1997;24:39–45. doi: 10.1023/A:1007927906986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M, Nakamura T, Matsuda C, Hattori T, Wakitani S, Yoshida T. In vitro proliferation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells employing donor serum and basic fibroblast growth factor. Cytotechnology. 2003;43:89–96. doi: 10.1023/B:CYTO.0000039911.46200.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M, Kitabayashi T, Ito S, Fujiwara M, Tokuda A. Noninvasive measurement of three-dimensional morphology of adhered animal cells employing phase-shifting laser microscope. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:054010-1–054010-5. doi: 10.1117/1.2779350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M, Kitabayashi T, Koizumi S, Hirose H, Kondo S, Fujiwara M, Ueno K, Misawa H, Hosokawa Y, Masuhara H, Wakitani S. Correlation between cell morphology and aggrecan gene expression level during differentiation from mesenchymal stem cells to chondrocytes. Biotechnol Lett. 2008;30:1189–1195. doi: 10.1007/s10529-008-9683-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumitsu A, Wakitani S, Takagi M. Noninvasive estimation of cell cycle phase and proliferation rate of human mesenchymal stem cells by phase-shifting laser microscopy. Cytotechnology. 2009;59:161–167. doi: 10.1007/s10616-009-9209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumitsu A, Wakitani S, Takagi M. Noninvasive discrimination of human normal cells and malignant tumor cells by phase-shifting laser microscopy. J Biosci Bioeng. 2010;109:499–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]