Abstract

Background

Production of fuels from the abundant and wasteful CO2 is a promising approach to reduce carbon emission and consumption of fossil fuels. Autotrophic microbes naturally assimilate CO2 using energy from light, hydrogen, and/or sulfur. However, their slow growth rates call for investigation of the possibility of heterotrophic CO2 fixation. Although preliminary research has suggested that CO2 fixation in heterotrophic microbes is feasible after incorporation of a CO2-fixing bypass into the central carbon metabolic pathway, it remains unclear how much and how efficient that CO2 can be fixed by a heterotrophic microbe.

Results

A simple metabolic flux index was developed to indicate the relative strength of the CO2-fixation flux. When two sequential enzymes of the cyanobacterial Calvin cycle were incorporated into an E. coli strain, the flux of the CO2-fixing bypass pathway accounts for 13 % of that of the central carbon metabolic pathway. The value was increased to 17 % when the carbonic anhydrase involved in the cyanobacterial carbon concentrating mechanism was introduced, indicating that low intracellular CO2 concentration is one limiting factor for CO2 fixation in E. coli. The engineered CO2-fixing E. coli with carbonic anhydrase was able to fix CO2 at a rate of 19.6 mg CO2 L−1 h−1 or the specific rate of 22.5 mg CO2 g DCW−1 h−1. This CO2-fixation rate is comparable with the reported rates of 14 autotrophic cyanobacteria and algae (10.5–147.0 mg CO2 L−1 h−1 or the specific rates of 3.5–23.7 mg CO2 g DCW−1 h−1).

Conclusions

The ability of CO2 fixation was created and improved in E. coli by incorporating partial cyanobacterial Calvin cycle and carbon concentrating mechanism, respectively. Quantitative analysis revealed that the CO2-fixation rate of this strain is comparable with that of the autotrophic cyanobacteria and algae, demonstrating great potential of heterotrophic CO2 fixation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13068-015-0268-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Carbon fixation, CO2-fixation rate, Heterotrophic microbe, Carbonic anhydrase, Rubisco

Background

The wasteful greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2) is a potential raw material for production of chemicals and fuels [1]. To this end, energy input is required since the carbon in CO2 is in its highest oxidation state. During the past 5 years, a variety of chemicals including ethanol [2–4], n-butanol [5–8], acetone [9], isobutyraldehyde [7], lactic acid [10–12], isoprene [13], 1,2-propanediol [14], methane [15], and biodiesel [16, 17] have been produced from CO2 by engineered autotrophic microbes such as cyanobacteria and algae, using light as the energy resource. Apart from the light, autotrophic microbes can also use hydrogen and/or sulfur as the energy source for CO2 assimilation under mild conditions [18].

Heterotrophic microbes usually do not assimilate CO2 through the central metabolism. Recent studies indicated that incorporation of several steps of a natural carbon fixation pathway into a heterotrophic microbe may create a CO2-fixing bypass pathway which enables the host to assimilate CO2 at the expense of carbohydrates. Examples include introduction of two enzymes of Calvin cycle into Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which resulted in enhanced CO2 recycling in an air-tight fermentor [19] and an increased ethanol yield [20], respectively.

Although these preliminary data suggested that heterotrophic CO2-fixation is feasible, little is done to quantitatively analyze and evaluate the process. To date, simple approaches capable of evaluating the CO2 flux in heterotrophic microbes are still lacking, since the metabolites of the CO2-fixing bypass pathway are indistinguishable from those of the central metabolic pathway. Due to lack of quantitative analysis, it remains unclear where the bottleneck for heterotrophic CO2-fixation is and whether the rate of heterotrophic CO2-fixation is higher, lower, or comparable with that of autotrophic CO2-fixation.

The aim of this study was to address the above issues through a quantitative and comprehensive analysis of the heterotrophic CO2-fixation process. To evaluate the strength of CO2 flux, a metabolic flux index, MFIh-CO2, was developed to indicate the metabolic flux ratio between the CO2-fixing bypass pathway and the central carbon metabolic pathway. The MFIh-CO2 was determined by addition of 13C-labeled sodium bicarbonate into the culture medium, followed by quantification of the isotropic-labeled and unlabeled forms of one intracellular metabolite by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Comparison of MFIh-CO2 values of several engineered CO2-fixing E. coli strains led to identification of the rate-limiting steps of heterotrophic CO2 fixation. The strain with the highest MFIh-CO2 value was aerobically cultivated in minimal medium supplemented with xylose in a chamber filled with 5 % CO2. The mass of fixed CO2 per liter culture of this strain per hour was calculated by the mass balance of carbon. The CO2-fixation rate in E. coli was then compared with those of several autotrophic microbes to evaluate the potential of heterotrophic CO2 fixation.

Results

Development of a metabolic flux index, MFIh-CO2, for relative quantification of heterotrophic CO2 fixation

It is costly and time-consuming to determine the absolute metabolic flux of CO2 fixation by quantifying every isotropic-labeled metabolite upon the feed of 13CO2 during cultivation. As the metabolic flux of the central metabolism for a given strain is quite stable, the relative metabolic flux of the CO2-fixing bypass pathway over that of the central carbon metabolic pathway may give a quantitative understanding on the efficiency of CO2 fixation. This relative value is then termed as the metabolic flux index of the heterotrophic CO2-fixation pathway, MFIh-CO2. At the conjunction of the CO2-fixing bypass pathway and the central pathway, the metabolite generated by the two pathways can be differentiated by using 13C-labeled CO2 and unlabeled sugar. The amount of the labeled and unlabeled forms of the joint metabolite can be determined and used to calculate the metabolic flux ratio of the two pathways to obtain the MFIh-CO2 value.

Herein, we use a heterotrophic CO2-fixing E. coli strain as a model to elucidate how MFIh-CO2 is calculated. The strain was constructed by incorporating two sequential enzymes in the cyanobacterial Calvin cycle, phosphoribulokinase (PRK), and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) into the central metabolism of E. coli. The incorporated CO2-fixing bypass pathway starts at ribulose 5-phosphate (Ru5P) in the pentose phosphate pathway of the central metabolism and ends at 3-phosphoglycerate (3PGA) in the glycolysis of the central metabolism (Fig. 1). When the strain is cultured in medium supplemented with 13C-labeled sodium bicarbonate, intracellular 13CO2, either generated by diffusion of the extracellular dissolved 13CO2 or by the equilibrium of 13C-labeled bicarbonate after its active transportation into cell, will be used as the substrate for Rubisco.

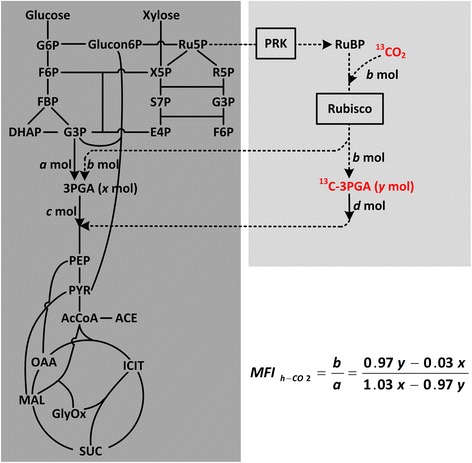

Fig. 1.

Metabolic pathway of a CO2-fixing E. coli. The central carbon metabolic pathway is shaded in dark gray, while the introduced CO2-fixation bypass pathway composed of PRK and Rubisco is shaded in light gray. The metabolic flux index of heterotrophic CO2-fixation, MFIh-CO2, can be calculated by the equation at the bottom right, using the determined amount of unlabeled 3PGA (x mol) and 13C-labbled 3PGA (y mol). 3PGA, 3-phosphoglycerate; AcCoA acetyl-CoA, ACE acetate, DHAP dihydroxyacetone phosphate, E4P erythrose-4-phosphate, F6P frutose-6-phosphate, FBP fructose-1,6-biphosphate, G3P glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, G6P glucose-6-phosphate, Glucon6P gluconate-6-phosphate, GlyOx glyoxylate, ICIT isocitrate, MAL malate, OAA oxaloacetate, PEP phosphoenolpyruvate, PRK phosphoribulokinase, PYR pyruvate, R5P ribose-5-phosphate, Ru5P ribulose-5-phosphate, Rubisco ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, RuBP ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate, S7P sedoheptulose-7-phosphate, SUC succinate, X5P xylulose-5-phosphate

As shown in Fig. 1, we assume a mole of 3PGA is generated from the central pathway and b mole of 13CO2 is fixed by the Rubisco pathway in a given period of time. Then (a + b) mole of unlabeled 3PGA and b mole of 13C-3PGA are generated. At the same period of time, we assume c mole of unlabeled 3PGA and d mole of 13C-3PGA are channeled into the downstream metabolism. It was reported that a small fraction of 13C isotope was coupled with all natural 12C-containing compounds [21–23]. We then cultivated E. coli strains in medium free of any carbon isotope and determined the ratio of 13C-3PGA to the unlabeled 3PGA as the basal isotopic level. The ratio was 3.45 % as shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1. We thus assume that 3.45 % of unlabeled 3PGA will convert to its isotopic form. Therefore, the actually detected molar amount of 13C-3PGA (y) can be calculated by Eq. (1), while the actually detected unlabeled 3PGA (x) can be calculated by Eq. (2).

| 1 |

| 2 |

Under a metabolic steady-state, the relationship of d, c, x, and y is shown in Eq. (3).

| 3 |

Solution to the equations deduces Eq. (4).

| 4 |

In this case, only the concentration of 13C-labeled and unlabeled 3PGA are required to be determined to calculate the MFIh-CO2. Compared with quantification of all intracellular isotropic metabolites to calculate the absolute metabolic flux, we argue that the determination of MFIh-CO2 to evaluate the relative metabolic strength of the CO2-fixation pathway would be a simple and convenient alternative.

Construction of a heterotrophic CO2-fixing E. coli

The Rubisco-encoding genes rbcL-rbcX-rbcS from Synechococcus sp. PCC7002 and the PRK-encoding gene prk from Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 were cloned into pET30a as described previously [24]. The resulted plasmid was designated as pET-RBC-PRK in this study. To verify the function of CO2-fixation pathway, Rubisco, and/or PRK were deactivated by introducing site-directed mutations to their conserved catalytic residues, yielding another three plasmids, pET-RBC197-PRK, pET-RBC-PRK2021, and pET-RBC197-PRK2021. Among them, RBC197 indicates a K197M mutation in the conserved catalytic site of the large subunit of Rubisco [25], and PRK2021 carries K20M and S21A mutations in the conserved nucleotide-binding sites of ATP-binding proteins [26].

Considerable amount of soluble expression of Rubisco under the T7 promoter was observed in strain BL21(DE3) carrying plasmid pET-RBC-PRK upon IPTG induction (Additional file 1: Figure S2). It was reported that the catalytic product of PRK, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate, could not be metabolized by E. coli and thus caused growth arrest to the cell [24, 27]. Retarded cell growth was indeed seen for strain BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC197-PRK with a deactivated Rubisco (Fig. 2b). Hence, the prk gene was leakily expressed without induction of its tryptophan-regulated promoter trpR-Ptrp to avoid severe growth inhibition. It is noteworthy that expression of Rubisco and PRK in E. coli BL21(DE3) increased cell growth in the late-phase of induction compared with the strain harboring the empty plasmid pET30a without any gene cloned (Fig. 2b). However, this increase appeared not to be the function of enzymes, as similar increases of growth were also seen in the strains transformed with pET-RBC197-PRK containing the deactivated PRK (Fig. 2b) and pET-RBC197-PRK2021 containing both deactivated enzymes (Additional file 1: Figure S3).

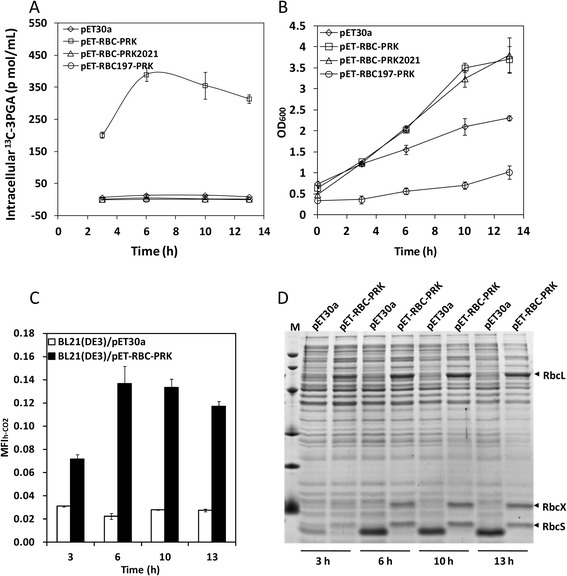

Fig. 2.

The intracellular 13C-3PGA (a), cell growth (b), MFIh-CO2 values (c), and soluble protein expression (d) of BL21(DE3) strains harboring different plasmids. All strains were 1:100 inoculated into LB medium containing 100 mM NaH13CO3 and shaken at 37 °C. When the culture reached the mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.4–0.6), 0.02 mM IPTG was added to induce Rubisco expression and the induction temperature was reduced to 22 °C (zero point). The PRK-encoding gene under the control of a tryptophan-regulated promoter trpR-Ptrp was leakily expressed in LB medium. RbcL and RbcS are the large and small subunits of Rubisco, which are encoded by rbcL and rbcS genes, respectively. RbcX is the specific chaperon of Rubisco, which is encoded by the rbcX gene. Molecular weight standards from top to bottom are 80, 60, 40, 30, 20, and 12 kDa

As shown in Fig. 2a, a significant increase of the 13C-3PGA along with induction time was observed for strain BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK cultivated with 100 mM NaH13CO3. Deactivation of either Rubisco or PRK in strain BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC197-PRK or BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK2021 decreased the 13C-3PGA production to the basal level of the control strain BL21(DE3)/pET30a. These results clearly demonstrated that the incorporated Rubisco pathway converted CO2 into 3PGA.

The MFIh-CO2 values of strain BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK at different induction times were calculated to evaluate its relative CO2 flux (Fig. 2c). For a period of 13 h induction, the MFIh-CO2 of the control strain BL21(DE3)/pET30a was below 0.03. Whereas, the MFIh-CO2 values of strain BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK was increased from 0.07 at 3 h to 0.13 at 6 h and then slightly decreased to 0.12 at 13 h. The increase of MFIh-CO2 values from 3 to 6 h was associated with the increase of Rubisco expression level (Fig. 2d), suggesting that the increased Rubisco activity contributed to the increased metabolic flux of CO2 fixation. When protein expression reached a high level from 6 h onwards, the MFIh-CO2 also reached its highest value.

Identification of the bottleneck of heterotrophic CO2 fixation

Rubisco was generally considered as the rate-determining step in the Calvin cycle of autotrophic microbes due to its extremely low catalytic efficiency [28, 29]. For the heterotrophic E. coli strain BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK harboring a partial Calvin cycle, accumulation of RuBP was observed even in the case of leaky-expression of PRK but overexpression of Rubisco. This result suggested that the Rubisco-catalyzed reaction is one of the rate-limiting steps of the CO2-fixing bypass pathway in heterotrophic E. coli (Additional file 1: Figure S4A). Owing to the difficulty in improving the catalytic activity of Rubisco, we attempted to increase the substrate supply (RuBP or CO2) for Rubisco to drive the reaction forward.

To increase the supply of RuBP, the weak promoter trpR-Ptrp for PRK expression was replaced by a strong promoter PT7, yielding a plasmid pET-RBC-T7-PRK. A significant increase of PRK expression level and an 8.6-fold increase of intracellular RuBP was observed after promoter replacement (Additional file 1: Figure S4). However, no significant difference in the MFIh-CO2 value (a P value of 0.36 using the Student T test) was observed after increasing the intracellular RuBP amount (Fig. 3), indicating that RuBP supply was not the rate-limiting factor.

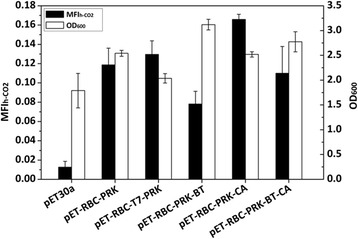

Fig. 3.

MFIh-CO2 values and OD600 of BL21(DE3) strains containing the indicated six plasmids. All strains were cultivated in LB medium containing 100 mM NaH13CO3 and expressed at 22 °C for 10 h in the presence of 0.02 mM IPTG

To increase CO2 supply, the unique cyanobacterial carbon concentrating mechanism (CCM) was introduced into E. coli. In cyanobacteria, bicarbonate is first transported to plasma membrane by bicarbonate transporter (BT), diffused into caboxysome, and then converted to CO2 by carbonic anhydrase (CA) and finally catalyzed by Rubisco therein [30]. To mimic this CCM in E. coli, single BT- or CA-encoding gene from Synechococcus sp. PCC7002, and their combinations, were respectively introduced into E. coli. The bicA gene, which encodes a Na+-dependent BT with high flux rate [31], was fused with promoter trpR-Ptrp and then inserted into pET-RBC-PRK to generate pET-RBC-PRK-BT. The MFIh-CO2 value of strain BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK-BT exhibited a decrease of 34.1 % compared with that of strain BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK (Fig. 3). This can be speculated that the increase of intracellular bicarbonate might cause pH variance and possibly affect expression or function of Rubisco or PRK. Moreover, bicarbonate has to be converted to CO2 so as to be catalyzed by Rubisco. The equilibrium of bicarbonate and CO2 under intracellular condition (e.g., pH 7.5) give the ratio of [HCO3-]/[CO2] to be 14 (the pKa of H2CO3 is 6.35 [32]). The increment of intracellular CO2 is thus only 7 % of that of bicarbonate. All these indicated that increasing the intracellular bicarbonate by BT expression was not an effective mean to improve heterotrophic CO2 fixation.

The CA-encoding gene (ccaA) was fused with a mutated constitutive bacteriophage promoter PL-AA [33] and then inserted into pET-RBC-PRK and pET-RBC-PRK-BT. The resultant strains BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK-CA and BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK-BT-CA showed MFIh-CO2 values of 0.17 and 0.11, respectively, which were 39.8 and 40.7 % higher than those of their respective parent strains without CA insertion (Fig. 3). Overexpression of CA increased the metabolic flux of heterotrophic CO2-fixation, indicating that CO2 supply is a limiting factor for CO2 fixation in E. coli.

Determination of the CO2-fixation rate of the heterotrophic E. coli

It was reported that E. coli metabolized 99 % of the sugar carbon into biomass, CO2, and acetate under aerobic condition [34]. However, no obvious fermentation product was detected for the CO2-fixing and control E. coli strains after 24 h of aerobic cultivation (Additional file 1: Figure S5). The carbon balance calculation of the control strain BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC197-PRK2021 without the ability of CO2-fixation also confirmed that the biomass and released CO2 accounted for 96 % of the consumed sugar carbon. According to the mass balance of carbon, the fixed CO2 of the CO2-fixing E. coli strain can be calculated by Eq. (5), where all values are in the molar amount of carbon.

| 5 |

The specific CO2 secretion rate of a given E. coli is a constant, which was 11.8 mmol g dry weight−1 h−1 reported in one literature [35] and 18.6 mmol g dry weight−1 h−1 in another [34]. Assuming the value is k, Eq. (5) can be transformed to Eq. (6).

| 6 |

Mass balance of carbon for the control strain BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC197-PRK2021, which harbored the two deactivated enzymes of the CO2-fixing pathway, can generate Eq. (7).

| 7 |

Assuming the specific CO2 secretion rate of the control strain is k', Eq. (7) will be transformed to Eq. (8).

| 8 |

Since CO2 is mainly generated from the tricarboxylic acid cycle of E. coli under aerobic conditions, the incorporated CO2-fixing pathway, which is a bypass of the upstream glycolysis, would not affect the specific CO2 secretion rate of the strain. Then, under the same cultivation condition, we can assume Eq. (9).

| 9 |

Solution to Eqs. (6), (8), and (9) generates Eq. (10).

| 10 |

Two CO2-fixing E. coli strains and the control strain were aerobically cultivated in 200 mL of M9 minimal medium supplemented with 10 g L−1 xylose in an Erlenmeyer flask. The flask was placed in an air-tight container (10 L) prefilled with 5 % CO2 and 95 % air and shaken at room temperature for 24 h. The pH variance, consumed xylose, and generated dry cell weight were determined (Table 1). All cultures maintained a stable pH, with a fluctuation of less than 0.2 unit. Calculation using Eq. (10) indicated that stains BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK and BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK-CA were able to fix 13.3 and 19.6 mg CO2 L−1 h−1, respectively. The 47.4 % of increment in the CO2-fixation rate after CA expression was similar to the 39.8 % of increment in the MFIh-CO2 value, which confirmed that the MFIh-CO2 was reliable for evaluating the CO2-fixation flux in the heterotrophic E. coli. The CO2-fixation rates of the heterotrophic E. coli strains constructed in this study were compared with those of the natural CO2-fixing autotrophic microbes (Table 2). Fourteen autotrophic microbes including microalgae, cyanobacteria, and non-green algae fixed CO2 at rates ranging from 10.5 to 147.0 mg CO2 L−1 h−1, with the median value of 21 mg CO2 L−1 h−1. The CO2-fixing E. coli strains were able to fix CO2 at rates of 13.3–19.6 mg CO2 L−1 h−1, which were comparable to the capacity of the autotrophic microbes.

Table 1.

The pH variance, consumed xylose, generated biomass, and calculated CO2-fixation rate of E. coli strains after 24 h of aerobic cultivation in 5 % CO2

| Strain | Initial pH | Final pHa | Consumed xylosea (mmol L−1) | Biomassa (DCW L−1) | CO2-fixation rate (mg L−1 h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK | 7.0 | 6.81 ± 0.06 | 13.7 ± 1.1 | 0.82 ± 0.33 | 13.3 ± 3.2 |

| BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK-CA | 7.0 | 6.81 ± 0.04 | 14.8 ± 1.5 | 0.87 ± 0.29 | 19.6 ± 4.0 |

| BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC197-PRK2021 | 7.0 | 6.87 ± 0.07 | 29.8 ± 4.7 | 1.59 ± 0.25 | – |

aThe cultivation was independently repeated for three times and the standard deviations were shown after the mean value

Table 2.

Comparison of the CO2-fixation rates of autotrophic and heterotrophic CO2-fixing microbes

| Species | CO2-fixation rate (mg L−1 h−1) | Biomass concentration (g DCW L−1) | Specific CO2-fixation ratea (mg g DCW−1 h−1) | CO2 concentration (%) | Culture condition | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autotrophic microbes | |||||||

| Microalgae | Chlorella pyrenoidosa SJTU-2 | 10.8 | 1.5 | 7.3 | 10 | 1 L flask with 800 mL WV | [52] |

| Dunaliella tertiolecta SAD-13.86 | 11.0 | 2.1 | 5.2 | 10 | 11 Lfermentor with 8 L WV | [53] | |

| Botryococcus braunii SAG-30.81 | 21.0 | 3.1 | 6.8 | 10 | 11 L fermentor with 8 L WV | [53] | |

| Scenedesmus obliquus SJTU-3 | 12.1 | 1.8 | 6.6 | 10 | 1 L flask with 800 mL WV | [52] | |

| Scenedesmus sp. NIER-10060 | 25.5 | 2.7 | 9.4 | 15 | Photobioreactor | [54] | |

| Chlorella vulgaris LEB-104 | 10.5 | 1.9 | 5.4 | 10 | 11 L fermentor with 8 L WV | [53] | |

| Chlorella Vulgaris NIER-10003 | 19.2 | 1.9 | 10.2 | 15 | Photobioreactor | [54] | |

| Chlorella vulgaris | 53.0 | 5.7 | 9.3 | 5 | Photobioreactorc | [55] | |

| Cyanobacteria | Spirulina sp. | 17.0a | 4.8 | 3.5 | 6 | 2 L vertical tubular photobioreactor with 1.8 L WV | [56] |

| Microcystis aeruginosa NIER-10037 | 20.4 | 2.3 | 8.8 | 15 | Photobioreactor | [54] | |

| Microcystis ichthyoblabe NIER-10040 | 21.7 | 2.2 | 9.8 | 15 | Photobioreactor | [54] | |

| Anabaena sp. ATCC 33047 | 60.4 | 2.7 | 22.4 | 0.03b | Glass bubble column photobioreactor | [57] | |

| Aphanothece microscopica | 109.0 | 5.1 | 21.4 | 15 | Glass bubble column photobioreactor | [58] | |

| Non-green algae | Phaeodactylum tricornutum | 147.0 | 6.2 | 23.7 | 40 | Photobioreactor | [59] |

| Heterotrophic microbes | |||||||

| Bacteria | E. coli JB | 5.8 | 6.1c | 0.95 | 0.03 | 3 L fermentor with 1 L WV | [19] |

| E. coli BL21(DE3)/PET-RBC-PRK | 13.3 | 0.82 | 16.2 | 5 | 1 L flask with 200 mL WV | This study | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3)/PET-RBC-PRK-CA | 19.6 | 0.87 | 22.5 | 5 | 1 L flask with 200 mL WV | This study | |

DCW dry cell weight, WV working volume

aCalculated by the CO2-fixation rate in the unit of mg L−1 h−1 divided by the biomass concentration in the unit of g DCW L−1

bCalculated by multiplying the reported OD600 (17.63) by our experimentally determined dry cell weight of E. coli (0.35 g L−1 OD600 −1)

cSequential photobioreactor using recycle water

Discussion

Recycling CO2 directly into fuels or chemicals is a potential approach to reduce carbon emission as well as to resolve energy crisis [6, 7]. The past 5 years have witnessed great success in production of CO2-derived molecules that have potential to be used as fuels and chemicals by autotrophic microbes. Quantitative analysis in this study revealed that an engineered heterotrophic E. coli could assimilate CO2 at a rate comparable to that of the autotrophic cyanobacteria and algae. It is noteworthy that the specific CO2-fixation rates of the E. coli strains were superior to most of the autotrophic microbes listed in Table 2. Since E. coli can easily grow to a high density in fermentors under well-controlled conditions, we believe that heterotrophic microbes might be an alternative candidate for CO2 fixation with great potential.

The most striking advantage of using heterotrophic microbes for CO2 fixation is their fast growth rates. The doubling times for E. coli and yeast are only 20 min [36] and 2 h [37], respectively, whereas those for common cyanobacteria and algae are in the range of 8–44 h [38, 39]. Most autotrophic microbes use photosynthesis to provide energy for CO2 assimilation and ultimately biomass accumulation. The theoretical maximum of solar energy conversion efficiency in photosynthesis is only 8–10 % [40], whereas the actual values for several species of cyanobacteria, microalgae, and plants do not exceed 3 % [41]. The low efficiency of photosynthesis can be ascribed to many inherent factors including insufficient absorption of all light wavelengths during light-dependent reactions and low carboxylation activity of Rubisco and existence of energy-consuming photorespiration during light-independent reactions [42]. Although many efforts have been made [43, 44], dramatic increases in photosynthetic efficiency as well as growth rate are still big challenges for autotrophic microbes [44]. However, billions of years of evolution have enabled the heterotrophic microbes to efficiently assimilate the high-energy sugars to generate both carbon backbone and energy at the same time. Therefore, heterotrophic microbes might be a better choice for CO2 fixation, since the fixed CO2 can be easily joined into the central metabolism and then be efficiently metabolized.

For the current version of the CO2-fixing E. coli strain constructed in this study, CO2 was fixed at the expense of sugar consumption because all energy required for CO2 fixation comes from sugar. However, it is not unbelievable that CO2 fixation can occur without sugar consumption in heterotrophic microbes once energy can be supplied from other sources. The pioneer work by Liao’s group has demonstrated that electricity can be used as the sole energy to convert CO2 to higher alcohols in Ralstonia eutropha [8], opening the door of employing other energy forms for CO2 fixation.

There is no doubt that improving the carboxylation activity of Rubisco is the ultimate way to increase the efficiency of CO2 fixation in both autotrophic and heterotrophic microbes. However, decades of Rubisco engineering gained limited success [24, 45]. In this work, the difficulty of Rubisco in access to CO2 was found to be another limiting factor of heterotrophic CO2 fixation. Expression of the CA from Synechococcus sp. PCC7002 under a weak constitutive promoter increased the E. coli CO2-fixation rate by 47.4 %. It is thus suggested that screening of the CA gene and optimization of its expression might be feasible ways to further improve the heterotrophic CO2-fixation rate. CA, which catalyzes the reversible interconversion of CO2 and HCO3−, is widely existed in animals, plants, archaebacteria, and eubacteria, and plays an important role in many physiological functions [46]. Although some CAs prefer the direction of CO2 hydration, the carboxysomal CAs in cyanobacteria and some chemoautotrophic bacteria favor the direction of HCO3− dehydration. To date, two forms of carboxysomal CAs (α and β), which are encoded by three types of genes with distinct sequences and structures (CsoSCA for α-CA and CcaA and CcmM for β-CA), were reported [47, 48]. The selected CA-encoding gene from Synechococcus sp. PCC7002 in this study was the CcaA gene. Whether the other two types of CA-encoding genes can be expressed in E. coli and whether their expression can increase the heterotrophic CO2-fixation rate are now under investigation by our group. Moreover, a stronger inducible promoter might be employed to enhance the CA expression in a controllable way to further improve the CO2 supply.

As a compensation for the low carboxylation activity of Rubisco, some autotrophic microbes have evolved some physical barriers (e.g., the semi-permeable caboxysome in cyanobacteria and the bundle sheath cells in C4 plants) to concentrate CO2 around Rubisco. Inspired by these, we suppose that constraining CO2 and the CO2-fixing enzyme in a microcompartment (e.g., reconstruction of the caboxysome in E. coli [49]) or recruiting the CO2-producing and CO2-fixing enzymes in a protein/RNA scaffold in E. coli might be an alternative way to further improve its CO2-fixation rate.

Conclusions

In this study, quantitative analysis approaches have been developed for CO2 fixation in heterotrophic microbes. The difficulty in access to CO2 was found to be a limiting factor for heterotrophic CO2 fixation. An E. coli strain capable of fixing CO2 at a rate of 19.6 mg CO2 L−1 h−1 or 22.5 mg CO2 g DCW−1 h−1 was constructed by incorporation of partial cyanobacterial Calvin cycle and carbon concentrating mechanism. This work demonstrated that CO2 fixation by the engineered heterotrophic E. coli can be as effective as the natural autotrophic cyanobacteria and algae, showing great potential of heterotrophic CO2 fixation.

Methods

Plasmids construction

All plasmids were constructed based on pET30a (Additional file 1: Table S1) and transformed to E. coli BL21 (DE3) for protein expression. The primers used are listed in Additional file 1: Table S2.

Isotropic assay for CO2-fixation efficiency

A fresh single colony of the strain was inoculated into LB medium containing 50 ng μL−1 kanamycin and cultured overnight at 37 °C. An aliquot of 100 μL of the overnight culture was inoculated into 40 mL fresh LB medium containing 50 ng μL−1 kanamycin, 100 mM hydroxyethylpiperazine ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), and 100 mM NaH13CO3 (Sigma). The culture was shaken at 37 °C until its OD600 reached 0.4–0.6. Then the temperature was reduced to 22 °C for maximal protein expression. At intervals, 3 OD600 of cells were harvested for SDS-PAGE and 8 mL of cells for intracellular metabolites extraction.

For SDS-PAGE, 3 OD600 of cells were resuspended in 1 mL buffer (100 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA) and sonicated. A 7 μL aliquot of the supernatant fraction (soluble protein) was subjected to SDS-PAGE (12 % w/v).

For intracellular metabolites extraction, all experiments were done on ice. At first, 10 mL of culture were rapidly centrifuged and washed in 10 mL cold (−20 °C) aqueous methanol solution (60 %, v/v) to quench cell metabolism as soon as possible. The suspension was clarified at −20 °C for 5 min at 20,000 g. The cell pellet was resuspended in 80 μL cold (−20 °C) aqueous methanol solution (60 %, v/v). After addition of 100 μL of 0.3 M KOH (dissolved in 25 % ethanol), the mixture was stored at −80 °C for more than 2 h to break the cell wall. The alkaline mixture was thawed on ice and neutralized by adding 2 μL of glacial acetic acid. Then the sample was centrifuged at −20 °C for 10 min at 20,000 g. The supernatant was stored at −80 °C before LC-MS/MS detection [50].

LC-MS/MS detection

Agilent 6460 series LC-MS/MS system equipped with a HPLC system and a triple-quadrupole Mass Spectrometer were used. All samples were separated by the reversed phase ion pair high performance liquid chromatography with Agilent XDC18 column (5uM, 150 mm × 4.6 mm). The negative ion and selected multiple reactions monitoring (MRM) mode were used for MS detection. Di-n-butylammonium acetate (DBAA) was used as the volatile ion pair reagent. DBAA and standard metabolites (3PGA and RuBP) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Methanol was purchased from Fisher Scientific [51]. The mobile phase was the mixture of solution A (water with 5 mM DBAA) and solution B (methanol with 5 mM DBAA) prepared at the gradient shown in Additional file 1: Table S3. The flow rate was 0.6 mL min−1. The injection volume was 50 μL and the column temperature was 40 °C.

The settings for MS were as follows: gas temperature, 350 °C; gas flow, 8 L min−1; nebulizer, 38 psi; sheath gas temperature, 350 °C; sheath gas flow, 9 L min−1; capillary, −3500 V; nozzle voltage, 500 V. The dwell time was set at 200 ms. The MRM parameters were optimized by the standards, and the detailed values for Q1 (m/z of precursor ion), Q3 (m/z of product ion), fragmentor, and collision energy (CE) were listed in Additional file 1: Table S4. All metabolites were quantified by their standard curves.

HPLC detection

The concentrations of xylose in medium before and after cultivation were determined using an Agilent 1200 high performance liquid chromatography (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a refractive index (RI) detector. An Aminex HPX-87 H organic acid analysis column (7.8 × 300 mm) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc, CA, USA) was maintained at 15 °C with 0.05 mM sulfuric acid as mobile phase. The injection volume was 10 μL and the flow rate was 0.5 mL min−1.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Zhensheng Xie (Lab of Proteomics, Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for her kind help on the LC-MS/MS and Fitsum Tigu Yifat (Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for his help in revising the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 program, 2011CBA00800), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21106175 and 31470231).

Abbreviations

- Rubisco

ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase

- PRK

phosphoribulokinase

- Ru5P

ribulose 5-phosphate

- 3PGA

3-phosphoglycerate

- BT

bicarbonate transporter

- CA

carbonic anhydrase

- MFIh-CO2

metabolic flux index of heterotrophic CO2 fixation

- DCW

dry cell weight

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry

- MRM

multiple reactions monitoring

- DBAA

Di-n-butylammonium acetate

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

Additional file

Table S1. Plasmids used in this study. Table S2. Oligonucleotides used in this study. Table S3. Gradient profile of LC-MS/MS. Table S4. Optimized parameters of MRM. Table S5. Carbon balance of strain BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC197-PRK2021 after 20 h of aerobic cultivation in M9/xylose medium. Figure S1. Determination of the basal level of 13C-3PGA which was naturally converted by the unlabeled 3PGA. Figure S2. Soluble Rubisco expression of BL21(DE3) strains harboring different plasmids. Figure S3. Cell growth for strains BL21(DE3)/pET30a, BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC-PRK, and BL21(DE3)/pET-RBC197-PRK2021. Figure S4. The amount of intracellular RuBP (A) and soluble proteins (B) for BL21(DE3) strains harboring plasmids pET30a, pET-RBC-PRK, pET-RBC197-PRK, and pET-RBC-T7-PRK, respectively. Figure S5. HPLC detection of fermentation products of different strains at 0 h and 24 h of cultivation.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YL developed the concept of this study. FG, GL, XZ, and ZC designed and performed experiments. FG, JZ, ZC, and YL analyzed the data. FG, ZC, and YL wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Fuyu Gong, Email: gongfuyu1987@126.com.

Guoxia Liu, Email: momo31707@126.com.

Xiaoyun Zhai, Email: zhaixiaoyun163@163.com.

Jie Zhou, Email: jiezhouw@im.ac.cn.

Zhen Cai, Email: caiz@im.ac.cn.

Yin Li, Email: yli@im.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Mikkelsen MJM, Krebs FC. The teraton challenge. A review of fixation and transformation of carbon dioxide. Energy Environ Sci. 2010;3:43–81. doi: 10.1039/B912904A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dexter J, Fu PC. Metabolic engineering of cyanobacteria for ethanol production. Energy Environ Sci. 2009;2:857–64. doi: 10.1039/b811937f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng MD, Coleman JR. Ethanol synthesis by genetic engineering in cyanobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:523–8. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.523-528.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo DX, Hu ZS, Choi DG, Thomas VM, Realff MJ, Chance RR. Life cycle energy and greenhouse gas emissions for an ethanol production process based on blue-green algae. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:8670–7. doi: 10.1021/es1007577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lan EI, Liao JC. ATP drives direct photosynthetic production of 1-butanol in cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:6018–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200074109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lan EI, Liao JC. Metabolic engineering of cyanobacteria for 1-butanol production from carbon dioxide. Metab Eng. 2011;13:353–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atsumi S, Higashide W, Liao JC. Direct photosynthetic recycling of carbon dioxide to isobutyraldehyde. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:1177–80. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H, Opgenorth PH, Wernick DG, Rogers S, Wu TY, Higashide W, et al. Integrated electromicrobial conversion of CO2 to higher alcohols. Science. 2012;335:1596. doi: 10.1126/science.1217643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou J, Zhang HF, Zhang YP, Li Y, Ma YH. Designing and creating a modularized synthetic pathway in cyanobacterium Synechocystis enables production of acetone from carbon dioxide. Metab Eng. 2012;14:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niederholtmeyer H, Wolfstadter BT, Savage DF, Silver PA, Way JC. Engineering cyanobacteria to synthesize and export hydrophilic products. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:3462–6. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00202-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angermayr SA, Paszota M, Hellingwerf KJ. Engineering a cyanobacterial cell factory for production of lactic acid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7098–106. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01587-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph A, Aikawa S, Sasaki K, Tsuge Y, Matsuda F, Tanaka T, et al. Utilization of lactic acid bacterial genes in Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 in the production of lactic acid. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77:966–70. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentley FK, Melis A. Diffusion-based process for carbon dioxide uptake and isoprene emission in gaseous/aqueous two-phase photobioreactors by photosynthetic microorganisms. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:100–9. doi: 10.1002/bit.23298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, Liao JC. Engineering a cyanobacterium as the catalyst for the photosynthetic conversion of CO2 to 1,2-propanediol. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12:4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunther A, Jakob T, Goss R, Konig S, Spindler D, Rabiger N, et al. Methane production from glycolate excreting algae as a new concept in the production of biofuels. Bioresour Technol. 2012;121:454–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.06.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang HY, Abunasser N, Garcia MED, Chen M, Ng KYS, Salley SO. Potential of microalgae oil from Dunaliella tertiolecta as a feedstock for biodiesel. Appl Energy. 2011;88:3324–30. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2010.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng XD, Li YJ, Fei XW. Microalgae: a promising feedstock for biodiesel. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2009;3:1008–14. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyle NR, Morgan JA. Computation of metabolic fluxes and efficiencies for biological carbon dioxide fixation. Metab Eng. 2011;13:150–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhuang ZY, Li SY. Rubisco-based engineered Escherichia coli for in situ carbon dioxide recycling. Bioresour Technol. 2013;150:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.09.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guadalupe-Medina V, Wisselink HW, Luttik MAH, de Hulster E, Daran JM, Pronk JT, et al. Carbon dioxide fixation by Calvin-Cycle enzymes improves ethanol yield in yeast. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6:125–36. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedli H, Lötscher H, Oeschger H, Siegenthaler U, Stauffer B. Ice core record of the 13C/12C ratio of atmospheric CO2 in the past two centuries. Nature. 1986;324:237–8. doi: 10.1038/324237a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuiver M, Braziunas TF. Tree cellulose 13C/12C isotope ratios and climatic change. Nature. 1987;328:58–60. doi: 10.1038/328058a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ciais P, Tans PP, Trolier M, White JWC, Francey RJ. A large northern hemisphere terrestrial CO2 sink indicated by the 13C/12C ratio of atmospheric CO2. Science. 1995;269:1098–102. doi: 10.1126/science.269.5227.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai Z, Liu G, Zhang J, Li Y. Development of an activity-directed selection system enabled significant improvement of the carboxylation efficiency of Rubisco. Protein Cell. 2014;5:552–62. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0072-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleland WWAT, Gutteridge S, Hartman FC, Lorimer GH. Mechanism of Rubisco: the carbamate as general base. Chem Rev. 1998;98:549–62. doi: 10.1021/cr970010r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins CF, Hiles ID, Salmond GP, Gill DR, Downie JA, Evans IJ, et al. A family of related ATP-binding subunits coupled to many distinct biological processes in bacteria. Nature. 1986;323:448–50. doi: 10.1038/323448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parikh MR, Greene DN, Woods KK, Matsumura I. Directed evolution of RuBisCO hypermorphs through genetic selection in engineered E. coli. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2006;19:113–9. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzj010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robert J, Spreitzer SRP, Satagopan S. Phylogenetic engineering at an interface between large and small subunits imparts land-plant kinetic properties to algal Rubisco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17225–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500972102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parry MA, Andralojc PJ, Mitchell RA, Madgwick PJ, Keys AJ. Manipulation of Rubisco: the amount, activity, function and regulation. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:1321–33. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zarzycki J, Axen SD, Kinney JN, Kerfeld CA. Cyanobacterial-based approaches to improving photosynthesis in plants. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:787–98. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Price GD, Woodger FJ, Badger MR, Howitt SM, Tucker L. Identification of a SulP-type bicarbonate transporter in marine cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:18228–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405211101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jn B. Carbon dioxide equilibria and their applications. Michigan, USA: Lewis Publishers Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alper H, Fischer C, Nevoigt E, Stephanopoulos G. Tuning genetic control through promoter engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12678–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504604102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischer E, Zamboni N, Sauer U. High-throughput metabolic flux analysis based on gas chromatography-mass spectrometry derived C-13 constraints. Anal Biochem. 2004;325:308–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X, Alonso AP, Allen DK, Reed JL, Shachar-Hill Y. Synergy between (13)C-metabolic flux analysis and flux balance analysis for understanding metabolic adaptation to anaerobiosis in E. coli. Metab Eng. 2011;13:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bremer H, Dennis PP. Modulation of chemical composition and other parameters of the cell by growth rate. E Coli Salmonella Cell Mol Biol. 1996;2:1553–69. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shastri AA, Morgan JA. Flux balance analysis of photoautotrophic metabolism. Biotechnol Prog. 2005;21:1617–26. doi: 10.1021/bp050246d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Griffiths MJ, Harrison STL. Lipid productivity as a key characteristic for choosing algal species for biodiesel production. J Appl Phycol. 2009;21:493–507. doi: 10.1007/s10811-008-9392-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hambourger M, Moore GF, Kramer DM, Gust D, Moore AL, Moore TA. Biology and technology for photochemical fuel production. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:25–35. doi: 10.1039/B800582F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melis A. Solar energy conversion efficiencies in photosynthesis: minimizing the chlorophyll antennae to maximize efficiency. Plant Sci. 2009;177:272–80. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stephenson PG, Moore CM, Terry MJ, Zubkov MV, Bibby TS. Improving photosynthesis for algal biofuels: toward a green revolution. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29:615–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kebeish R, Niessen M, Thiruveedhi K, Bari R, Hirsch HJ, Rosenkranz R, et al. Chloroplastic photorespiratory bypass increases photosynthesis and biomass production in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:593–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evans JR. Improving photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:1780–93. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.219006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitney SM, Houtz RL, Alonso H. Advancing our understanding and capacity to engineer nature’s CO2-sequestering enzyme, Rubisco. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:27–35. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.164814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitra M, Lato SM, Ynalvez RA, Xiao Y, Moroney JV. Identification of a new chloroplast carbonic anhydrase in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:173–82. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.037283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rae BD, Long BM, Badger MR, Price GD. Functions, compositions, and evolution of the two types of carboxysomes: polyhedral microcompartments that facilitate CO2 fixation in cyanobacteria and some proteobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77:357–79. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00061-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cannon GC, Heinhorst S, Kerfeld CA. Carboxysomal carbonic anhydrases: structure and role in microbial CO2 fixation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:382–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonacci W, Teng PK, Afonso B, Niederholtmeyer H, Grob P, Silver PA, et al. Modularity of a carbon-fixing protein organelle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:478–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108557109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo B, Groenke K, Takors R, Wandrey C, Oldiges M. Simultaneous determination of multiple intracellular metabolites in glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway and tricarboxylic acid cycle by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2007;1147:153–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uematsu K, Suzuki N, Iwamae T, Inui M, Yukawa H. Increased fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase in plastids enhances growth and photosynthesis of tobacco plants. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:3001–9. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang D, Han W, Li P, Miao X, Zhong J. CO2 biofixation and fatty acid composition of Scenedesmus obliquus and Chlorella pyrenoidosa in response to different CO2 levels. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:3071–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sydney EB, Sturm W, Carvalho JC, Thomaz-Soccol V, Larroche C, Pandey A, et al. Potential carbon dioxide fixation by industrially important microalgae. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:5892–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin H-F, Lim B-R, Lee K. Influence of nitrate feeding on carbon dioxide fixation by microalgae. Journal of environmental science and health. J Environ Sci Heal A. 2006;41:2813–24. doi: 10.1080/10934520600967928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lam MKLK. Effect of carbon source towards the growth of Chlorella vulgaris for CO2 bio-mitigation and biodiesel production. Int J Greenhouse Gas Control. 2013;14:169–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijggc.2013.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morais MG, Costa JA. Carbon dioxide fixation by Chlorella kessleri, C. vulgaris, Scenedesmus obliquus and Spirulina sp. cultivated in flasks and vertical tubular photobioreactors. Biotechnol Lett. 2007;29:1349–52. doi: 10.1007/s10529-007-9394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonzalez Lopez CV, Acien Fernandez FG, Fernandez Sevilla JM, Sanchez Fernandez JF, Ceron Garcia MC, Molina GE. Utilization of the cyanobacteria Anabaena sp. ATCC 33047 in CO2 removal processes. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100:5904–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jacob-Lopes E. CFLL, Franco TT. Biomass production and carbon dioxide fixation by Aphanothece microscopica Nägeli in a bubble column photobioreactor. Biochem Eng J. 2008;40:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2007.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mazzuca Sobczuk T, Garcia Camacho F, Camacho Rubio F, Acien Fernandez FG, Molina GE. Carbon dioxide uptake efficiency by outdoor microalgal cultures in tubular airlift photobioreactors. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;67:465–75. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(20000220)67:4<465::AID-BIT10>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]