Abstract

Background

Limited data exist about relatively recent trends in the magnitude and characteristics of patients who are rehospitalized shortly after admission for a non ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). This observational study describes decade-long trends (1999-2009) in the magnitude and characteristics of patients readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of hospitalization for an incident (initial) episode of NSTEMI.

Methods

We reviewed the medical records of 2,249 residents of the Worcester (MA) metropolitan area who were hospitalized for an initial NSTEMI in 6 biennial periods between 1999 and 2009 at 3 central MA medical centers.

Results

The average age of our study population was 72 years, 90% were white, and 46% were women. The proportion of patients who were readmitted to the hospital for any cause within 30 days after discharge for a NSTEMI remained unchanged between 1999 and 2009 (approximately 15%) in both crude and multivariable adjusted analyses. Slight declines were observed for cardiovascular disease-related 30-day readmissions over the ten-year study period. Women, elderly patients, those with multiple chronic comorbidities, a prolonged index hospitalization, and patients who developed heart failure during their index hospitalization were at higher risk for being readmitted within 30-days than respective comparison groups.

Conclusions

Thirty day hospital readmission rates after hospital discharge for a first NSTEMI remained stable between 1999 and 2009. We identified several groups at higher risk for hospital readmission in whom further surveillance efforts and/or tailored educational and treatment approaches remain needed.

Keywords: hospital readmissions, non ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction

Introduction

Coronary heart disease is a leading cause of morbidity, mortality, and functional disability in American adults (1-3). However, rapid and impactful management strategies have reshaped the contemporary epidemiology of patients admitted with an acute coronary event, with an increasing proportion of patients surviving their index hospitalization (2, 3). As such, insurance payers, physicians, and patients are focusing on a number of important post-discharge outcomes, most notably on the risk of rehospitalization (4, 5). Rehospitalization after an index coronary event has garned increased scrutiny during recent years since it is both common (1 in 5 Medicare beneficiaries is readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of being discharged for an acute myocardial infarction (AMI)) and costly (with estimated annual excess costs of $17 billion in the U.S.) (4-8).

Given the aging of the U.S. population, and increasing use of high-sensitivity biomarkers over the last 15 years, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) has become increasingly prevalent (2,3). Few studies have, however, examined the magnitude of, and trends over time therein, short-term hospital readmissions among patients discharged from the hospital after a NSTEMI (2, 3).

Reductions in hospital readmissions after an AMI will be facilitated by greater understanding of the magnitude, timing, and reasons for these events, as well as by identifying the characteristics of patients at high risk for being re-hospitalized (6-11). Using data from the Worcester Heart Attack Study (12-14), we examined overall, and decade long trends (1999-2009), in the magnitude, timing, and reasons for hospital readmission during the first 30 days after hospital discharge for an initial NSTEMI among residents of central Massachusetts.

Material and Methods

Data for this study were derived from the Worcester Heart Attack Study (12-14). This is an ongoing population-based investigation that is examining long-term trends in the incidence rates, hospital, and post-discharge case-fatality rates of AMI among residents of the Worcester (MA) metropolitan area.

For the present study we restricted our study sample to patients with a NSTEMI due to the relatively high prevalence of NSTEMI and the lack of published data about the characteristics of patients with NSTEMI readmitted to the hospital after an index hospitalization. A diagnosis of NSTEMI was accepted when elevations in cardiac biomarker assays, including troponin, were accompanied by typical acute clinical symptomatology and ST- depression and T inversion in the ECG (15, 16). We further restricted this patient population to those with an incident NSTEMI to avoid potential confounding by the patient's prior history of AMI. Based on the independent review of previous and current hospital medical records by trained nurse and physician abstractors, patients with a history of AMI were excluded from the present population (15, 16). Only patients who had their index hospitalization for AMI at the 3 largest tertiary care and community medical centers in central MA, which comprise the vast majority of all hospital admissions for AMI among residents of central MA, were included in the present study.

Data collection

Trained nurses and physicians abstracted demographic and clinical data from hospital medical records. Abstracted information included patient's age, sex, medical history, physiologic factors, laboratory test results, length of hospital stay, and hospital discharge status (12–14, 17). Information about the hospital use of important cardiac medications, coronary angiography, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery was collected. Development of several significant clinical complications (e.g., atrial fibrillation, cardiogenic shock, stroke, heart failure) during the patient's index hospitalization was defined according to standardized criteria (18–21).

A hospital readmission was defined as the first admission to a participating study hospital within 30 days of discharge after the patient's index hospitalization for an initial NSTEMI during the years under study. Readmission data were abstracted from the electronic medical records data warehouse at our principal study sites, namely the University of Massachusetts-Memorial Medical Center and Saint Vincent Medical Center. Two investigators adjudicated whether the principal reason for readmission was cardiovascular (CVD) or non-CVD related. Indications for CVD related hospitalizations included conditions such as an acute coronary syndrome, diabetes mellitus, and chronic ischemic heart disease. Examples of non-CVD related hospitalizations included urinary tract infections and bone fractures. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Data Analysis

The rates of hospital readmissions during the first 30 days after hospital discharge were calculated in a standard manner. Differences in the characteristics of patients who were readmitted to the hospital during the first 30 days after discharge for an initial NSTEMI were compared to those who were not readmitted through the use of chi-square tests for discrete variables and t-tests for continuous variables. For ease of analysis and interpretation, trends in 30-day hospital readmissions were examined during the aggregated study years of 1999/01, 2003/05, and 2007/09. Crude and multivariable adjusted logistic regression analyses were used to examine demographic, clinical, and other factors associated with 30-day readmissions in study patients as well as changes over time in the rates of hospital readmissions.

Results

A total of 2,249 residents of central MA were hospitalized with a confirmed initial NSTEMI at the 3 major medical centers serving residents of central MA during the years under study. The average age of this patient population was 72 years, almost half were women, and 90% were white.

Magnitude of hospital readmissions

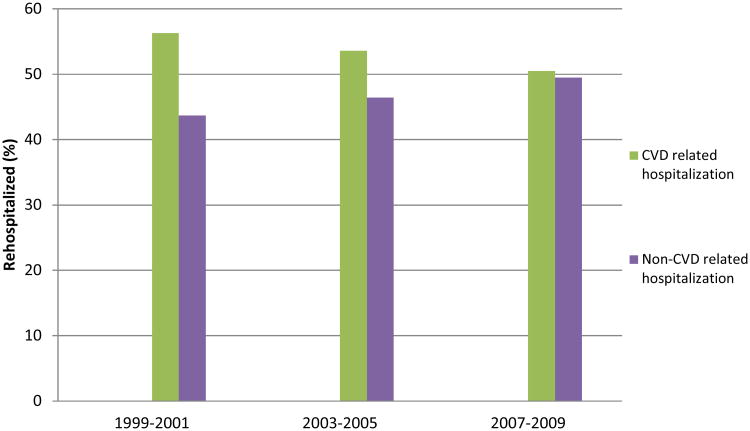

Approximately 15% of patients were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge after their index hospitalization for a first NSTEMI. The 30-day all-cause readmission rates remained relatively stable between 1999 (15.2%) and 2009 (14.4%), respectively. We examined the risk of being re-hospitalized during earlier as compared with the most recent years under study after controlling for several potentially confounding factors (e.g., age, sex, and history of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, hypertension, stroke, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease). The multivariable adjusted odds of experiencing a 30-day hospital readmission was 1.05 (95%CI 0.78; 1.40) and 1.06 (95% CI 0.78; 1.46) during 2003/05 and 2007/09, respectively, compared with the referent period of 1999/2001. In terms of the reasons for these readmissions, the proportion of CVD-related 30-day readmissions slightly decreased from 56.3% in 1999/2001 to 50.5% in 2007/09 (p=0.77) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trends in 30-day Cardiovascular Disease and Non-Cardiovascular Disease Related Hospitalizations.

Characteristics of patients who were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days after hospital discharge

Overall, older patients and women were more likely to have been re-hospitalized over the subsequent 30 days after discharge for a first NSTEMI as compared with younger patients and men (Table 1). Patients who were readmitted to participating hospitals during this period were more likely to have been previously diagnosed with several comorbidities, including heart failure, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and peripheral vascular disease, singly and in combination, as compared with those who were not readmitted to these hospitals during this period (Table 1). Patients who were readmitted during the first month after hospital discharge also had a longer average index hospital stay (7.0 vs. 5.5 days) and were more likely to have developed heart failure during their acute hospitalization than those who were not re-hospitalized during this period (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with an initial NSTEMI who were rehospitalized within 30-days of hospital discharge.

| Characteristic | Re-hospitalized (n=335) (%) | Not re-hospitalized (n = 1,914) (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, years) | 72.3(12.4) | 71.1(14.4) | <0.001 |

| Male | 164(49.0) | 1,046(54.7) | 0.05 |

| Race, White | 298(89.0) | 1,713(85.2) | 0.54 |

| Season of hospitalization | |||

| Fall | 73(21.8) | 510(26.7) | 0.29 |

| Winter | 94(28.1) | 489(25.6) | |

| Spring | 92(27.5) | 517(27.0) | |

| Summer | 76(22.7) | 398(20.8) | |

| Hospitalized during a weekday | 254(75.8) | 1,443(75.4) | 0.87 |

| Medical History | |||

| Atrial Fibrillation | 59(17.6) | 280(14.6) | 0.16 |

| Heart Failure | 96 (28.7) | 351(18.3) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 246(73.4) | 1,367(71.4) | 0.45 |

| Stroke | 46(13.7) | 200(10.5) | 0.80 |

| Diabetes | 140(41.8) | 565(29.5) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 68(20.3) | 334(17.5) | 0.21 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 85(25.4) | 297(15.5) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 76(22.7) | 273(14.3) | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 30(9.0) | 145(7.6) | 0.39 |

| Length of Stay at index hospitalization (mean, days) | 7.0(6.5) | 5.5(5.4) | <0.001 |

| Physiologic variables | |||

| Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, (mean, ml/min/1.73m2 ) | 53.1(21.9) | 57.7(22.6) | 0.51 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mean, mm Hg) | 144.4(32.2) | 145.4(31.1) | 0.42 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mean, mm Hg) | 74.8(17.9) | 79.0(19.4) | 0.07 |

| Serum Glucose (mean, mg/dl) | 175.1(78.6) | 162.9(75.9) | 0.41 |

| Total serum cholesterol(mean, mg/dl) | 171.5(48.5) | 179.2(46.2) | 0.36 |

| Complications during hospitalization | |||

| Cardiogenic shock | 11(3.3) | 53(2.8) | 0.60 |

| Heart Failure | 161 (48.1) | 650(34.0) | <0.001 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 74(22.1) | 411(21.5) | 0.80 |

| Stroke | 3(0.9) | 36(1.9) | 0.20 |

The proportion of patients who received evidence- based in-hospital medications and cardiac interventions was similar for those with and without a 30-day readmission; however, a slightly higher proportion of patients who were readmitted within 30 days received angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, beta-blockers, and underwent CABG surgery during their index hospitalization than those who were not re-admitted during this period (Table 2). The proportion of patients who received cardiac interventions significantly increased during the years under study, however, there were no between group differences noted in these trends among those who were and were not readmitted.

Table 2. Hospital medical management of patients with an initial NSTEMI who were rehospitalized within 30-days of hospital discharge.

| Re-hospitalized (n=335) (%) | Not re-hospitalized (n=1,914) (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Medications | |||

| Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor/Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 210(62.7) | 1,101(57.5) | 0.08 |

| Beta-Blockers | 307(91.6) | 1,714(89.6) | 0.24 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | 217(64.8) | 1,285(67.1) | 0.40 |

| Aspirin | 311(92.8) | 1,772(92.6) | 0.87 |

| Anticoagulants | 266(79.4) | 1,468 (76.7) | 0.28 |

| Cardiac Interventions | |||

| Cardiac Catheterization | 177 (52.8) | 1,049(54.8) | 0.50 |

| Percutaneous Coronary Intervention | 101(30.2) | 655(34.2) | 0.15 |

| Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery | 28(8.4) | 129(6.7) | 0.28 |

We performed a series of logistic regression analyses for purposes of examining demographic and clinical factors associated with 30-day hospital readmissions. The results of this multivariable adjusted analysis showed that those with a history of chronic kidney disease, who had 3 or more comorbidities previously diagnosed at the time of their acute hospitalization, and an index hospitalization of 4 days or longer had a markedly increased risk for being readmitted during the next 30 days than respective comparison groups. Patients who developed acute heart failure during hospitalization, and those who had a previous history of diabetes, had an approximate 35% higher risk of being readmitted to the hospital within 30 days than respective comparison groups (Table 3). When evidence-based medications and cardiac interventions (aspirin, beta-blockers, lipid lowering agents, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, cardiac catheterization, PCI, and CABG surgery) were included in the multivariable regression models, similar factors remained associated with hospital readmission and none of these evidenced- based medications or cardiac procedures were associated with a reduced risk of being readmitted to the hospital over the next 30 days.

Table 3. Factors associated with 30-day readmissions to the hospital after an initial NSTEMI.

| Multivariable Adjusted Odds Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | ||

| Age (years) | 65-74 | 1.16 (0.81,1.66)* |

| 75-84 | 1.09 (0.78,1.54) | |

| 85 and older | 0.72 (0.47,1.11) | |

| Male | 0.83 (0.65,1.06) | |

| Hospitalized during a weekday | 0.98 (0.74,1.29) | |

| Medical History | ||

| Atrial Fibrillation | 1.08 (0.76,1.53) | |

| Heart Failure | 1.23 (0.90,1.68) | |

| Hypertension | 0.85 (0.64,1.13) | |

| Stroke | 1.12 (0.78,1.62) | |

| Diabetes | 1.36 (1.04,1.76) | |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 1.04 (0.77,1.40) | |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 1.45 (1.06,1.98) | |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 1.35 (0.99,1.83) | |

| Length of Stay at index hospitalization | 1.53 (1.16;2.0) | |

| Number of comorbidities Any 3 | 1.46 (1.06,2.00) | |

| Any 4 or more | 1.86 (1.35,2.56) | |

| Complications during hospitalization | ||

| Heart Failure | 1.38 (1.05,1.82) | |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 0.84 (0.61,1.15) | |

| Stroke | 0.41 (0.12,1.35) | |

95% confidence intervals

Respective referent categories: age ≤65 years, female, absence of selected comorbidities, length of stay ≥4 days, number of comorbidities ≤2, absence of clinical complications during hospitalization

Discussion

In this large observational study of patients hospitalized for an initial NSTEMI between 1999 and 2009, we found that the rates of 30-day hospital readmissions remained relatively stable during the years under study. Factors associated with 30-day readmission included the presence of multiple chronic comorbidities, development of heart failure during hospitalization, and having a longer index hospital stay. During the period under study, the proportion of CVD-related readmissions slightly declined.

Trends in the magnitude of 30 day hospital readmissions

To our knowledge, there have been little published data describing trends in hospital readmissions among patients with an NSTEMI; thus, we are only able to compare our results with studies examining trends in 30-day readmission rates among patients hospitalized with AMI (22). Despite declining mortality rates among patients hospitalized with AMI, improved access to PCI, and greater utilization of evidence-based therapies, short-term hospital readmission rates have shown little, if any, improvement over time (23, 24). Our findings suggested little to no changes in 30-day readmission rates between 1999/01(15.2%) and 2007/09(14.4%). Moreover, there was no significant change in the odds of being readmitted to the hospital during earlier as compared with more recent years under study after controlling for a number of potentially confounding variables that might have affected the risk of hospital readmissions.

A cohort study of 3,010 patients hospitalized with a first AMI (70% NSTEMI, mean age 67 years) in Minnesota reported that 30-day readmissions slightly decreased between 1987 and 2010 (from 23% to 19%) (4). A national, decade-long, retrospective analysis of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with AMI found that the 30-day readmission rate remained unchanged between 1997 (20%) and 2007 (19%) (25). One possible explanation for the lack of change in the 30 day hospital readmission rates might be that advances in the treatment of patients with AMI may have increased survival for more severely ill patients, who in turn, would be more likely to be readmitted. Since hospital readmissions can create significant financial penalties for providers, further investigations should examine whether these trends in readmission rates are reflective of quality of care or to the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the populations under study.

Characteristics of readmitted patients

The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Dynamic Registry study of 11,000 patients with an acute coronary syndrome (mean age 64 years) found that women, those with several comorbidities, and patients who underwent emergency PCI had a higher risk for being readmitted to the hospital over the next 30 days than respective comparison groups (26). An analysis of more than 500,000 Medicare claims for AMI related hospitalizations identified patients 85 years and older and those with a history of renal disease or heart failure as being at increased risk for 30-day hospital readmissions (27). These results suggest that patients discharged from the hospital after AMI are increasingly older and more likely to present with several chronic conditions (28, 29).

Our findings suggest that women, elderly patients, and those with various comorbidities (e.g., heart failure, diabetes, chronic kidney disease) were at increased risk for having a hospital readmission within 30-days. Since patients with greater disease burden are more likely to experience higher readmission rates than their healthier counterparts, additional studies focusing on surveillance and treatment approaches for patients presenting with multiple comorbidities are necessary. For example, a greater emphasis on multidisciplinary management practices may insure that complex NSTEMI patients have adequate social and medical support to manage their comorbidities prior to hospital discharge and that they, and their caregivers, understand the post discharge instructions that have been discussed with them.

Our findings with regards to the lack of association between the receipt of various hospital cardiac medications and interventional procedures to 30 day readmission rates should not be interpreted that these treatment approaches are not of benefit to patients discharged from the hospital after a NSTEMI. We did not collect information about patient's post discharge management, dosages of medications received, or contraindications to the receipt of these medications.

Cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular related readmissions

There has been little investigation into the causes for 30-day readmissions for patients discharged from the hospital after a NSTEMI. The Minnesota study of patients with AMI found that 43% of those with a 30-day readmission were hospitalized due to complications from the MI or its treatment. Women and those with an NSTEMI were more likely to have a non-MI related readmission (4). A study of 3,225 patients undergoing PCI (mean age 66 years) at a single medical center between 2007-2010 reported that, among patients who were rehospitalized within the first month after hospital discharge, 40% were diagnosed as having a condition unrelated to the index hospitalization for PCI (30).

We found a slight decrease in the proportion of CVD-related readmissions during the period under study. One possible explanation for the corresponding slight increase in the proportion of non-CVD related readmissions could be that effective cardiac treatments are being more timely and aggressively implemented, resulting in a reduced risk of readmissions due to cardiac related concerns. Since approximately one half of all repeat hospitalizations were, however, due to non-cardiac reasons in the present study, more detailed information on the reasons for hospital readmissions, as well as use of other health care services during the month following hospital discharge for an NSTEMI, should be collected to help develop targeted interventions and identify at risk patients to prevent further rehospitalizations.

Study strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this study include the large patient sample hospitalized with a first confirmed NSTEMI and the collection of data over a decade long period. Our sample included a large representation of women and patients with comorbidities. We also acknowledge several limitations associated with this study. The predominantly Caucasian study population limits generalizability to other racial and ethnic groups. We did not analyze characteristics that have previously been associated with risk of readmission after an AMI including quality of discharge planning, hospitalizations in the prior 6 months (31), enrollment in a cardiac rehabilitation program (32), and various psychosocial and socioeconomic factors (33), nor were we able to assess patient's adherence to various prescribed medications after hospital discharge.

Conclusions

The results of this study of more than 2,200 patients hospitalized with a first NSTEMI in 3 major central MA medical centers suggest that there was little change in the 30-day hospital readmission rates between 1999 and 2009; approximately 1 in every 7 patients discharged from the hospital were readmitted to the hospital over the next month for any reason. We found a slight decrease in the proportion of CVD-related readmissions during the period under study, with more than one half of patients being readmitted for a CVD related reason. Furthermore, older patients, those with several comorbidities, who had a longer hospital stay, or who developed heart failure during their index hospitalization remained at higher risk for being rehospitalized. Enhanced surveillance efforts as well as tailored educational approaches should focus on those at higher risk for being readmitted to the hospital after a NSTEMI. Novel approaches remain needed to decrease hospital readmission rates, possible risk and situational factors for hospital readmission need to be identified, and risk prediction models should be developed to reduce hospital readmission rates and use of the emergency department after being admitted to the hospital with an NSTEMI.

30-day hospital readmission rates after NSTEMI remained stable from 1999 to 2009

More than one half of NSTEMI patients were readmitted for a CVD related reason

The elderly and patients with comorbidities were at greatest risk for readmission.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: National Institutes of Health (RO1 HL35434)

Dr. Tisminetzky is funded by Diversity Supplement R01 HL35434-29. Partial salary support is additionally provided to Drs. Goldberg, Saczynski, and Gore by National Institutes of Health grant U01HL105268-01 Dr. McManus is supported by award number KL2RR031981 funded through the National, Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Dr. Saczynski is supported by award number K01AG033643 from the National Institute on Aging

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest to report for any of the authors.

All authors had access to the data and had a role in writing this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute. Morbidity and Mortality: 2012 Chartbook on Cardiovascular, Lung and Blood Diseases. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers WJ, Frederick PD, Stoehr E, Canto JG, Ornato JP, Gibson CM, Pollack CV, Jr, Gore JM, Chandra-Strobos N, Peterson ED, French WJ. Trends in presenting characteristics and hospital mortality among patients with ST elevation and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J. 2008;156:1026. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bode C, Zirlik A. STEMI and NSTEMI: the dangerous brothers. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1403–1404. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunlay S, Weston S, Killian Thirty-Day Rehospitalizations after Acute Myocardial Infarction. A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:11–18. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Press MJ, Scanlon DP, Navathe AS, Zhu J, Chen W, Mittler JN, Volpp KG. The importance of clinical severity in the measurement of hospital readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1997-2007. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(6):653–65. doi: 10.1177/1077558713496167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai MM, Stauffer BD, Feringa HH, Schreiner GC. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(5):500–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.832949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker DW, Einstadter D, Husak SS, Cebul RD. Trends in postdischarge mortality and readmissions: has length of stay declined too far? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:538–544. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.5.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Axon RN, Williams MV. Hospital readmission as an accountability measure. JAMA. 2011;305(5):504–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkman B, Abrams RD. Factors related to hospital readmission of elderly cardiac patients. Soc Work. 1986;31:99–103. doi: 10.1093/sw/31.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heller RF, Fisher JD, D'Este CA, Lim LLY, Dobson AJ, Porter R. Death and readmission in the year after hospital admission with cardiovascular disease: the Hunter Area Heart and Stroke Register. Med J Aust. 2000;172:261–265. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb123940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maynard C, Every NR, Weaver WD. Factors associated with rehospitalization in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:777–779. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00515-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Floyd KC, Yarzebski J, Spencer FA, Lessard D, Dalen JE, Alpert JS, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. A 30 year perspective (1975–2005) into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with initial acute myocardial infarction: Worcester Heart Attack Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:88–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.811828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. A 25-year perspective into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (the Worcester Heart Attack Study) Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1373–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Recent changes in attack and survival rates of acute myocardial infarction (1975 through 1981). The Worcester Heart Attack Study. JAMA. 1986;255:2774–2779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McManus DD, Gore J, Yarzebski J, Spencer F, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am J Med. 2011;124:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD, Writing Group on the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Katus HA, Apple FS, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, Chaitman BA, Clemmensen PM, Johanson P, Hod H, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Bonow RO, Pinto F, Gibbons RJ, Fox KA, Atar D, Newby LK, Galvani M, Hamm CW, Uretsky BF, Steg PG, Wijns W, Bassand JP, Menasché P, Ravkilde J, Ohman EM, Antman EM, Wallentin LC, Armstrong PW, Simoons ML, Januzzi JL, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Luepker RV, Fortmann SP, Rosamond WD, Levy D, Wood D, Smith SC, Hu D, Lopez-Sendon JL, Robertson RM, Weaver D, Tendera M, Bove AA, Parkhomenko AN, Vasilieva EJ, Mendis S ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551–2567. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM. Decade-long trends and factors associated with time to hospital presentation in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the Worcester Heart Attack Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3217–3223. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saczynski JS, McManus D, Zhou Z, Spencer F, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. Trends in atrial fibrillation complicating acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Gore JM, Lessard D, Yarzebski J. Thirty year trends (1975– 2005) in the magnitude of, management of, and hospital death rates associated with cardiogenic shock in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population based perspective. Circulation. 2009;119:1211–1219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saczynski JS, Spencer FA, Gore JM, Gurwitz JH, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Twenty-year trends in the incidence rates of stroke complicating acute myocardial infarction: the Worcester Heart Attack Study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2104–2110. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McManus DD, Chinali M, Saczynski JS, Gore JM, Yarzebski J, Spencer FA, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Thirty year trends in heart failure in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montalescot G, Dallongeville J, Van Belle E, Rouanet S, Baulac C, Degrandsart A, Vicaut E OPERA Investigators. STEMI and NSTEMI: are they so different? 1 year outcomes in acute myocardial infarction as defined by the ESC/ACC definition (the OPERA registry) Eur Heart J. 2007;28(12):1409–1417. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2014 Update A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):E28–E292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langabeer JR, Henry TD, Kereiakes DJ, Dellifraine J, Emert J, Wang Z, Stuart L, King R, Segrest W, Moyer P, Jollis JG. Growth in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Capacity Relative to Population and Disease Prevalence. JAHA. 2013;2(6):1–7. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Press MJ, Scanlon DP, Navathe AS, Zhu J, Chen W, Mittler JN, Volpp KG. The Importance of Clinical Severity in the Measurement of Hospital Readmission Rates for Medicare Beneficiaries, 1997-2007. Medical Care Research and Review. 2013;70(6):653–665. doi: 10.1177/1077558713496167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ricciardi MJ, Selzer F, Marroquin OC, Holper EM, Venkitachalam L, Williams DO, Kelsey SF, Laskey WK. Incidence and predictors of 30-day hospital readmission rate following percutaneous coronary intervention (from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Dynamic Registry) Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(10):1389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, Bueno H, Ross JS, Horwitz LI, Barreto-Filho JA, Kim N, Bernheim SM, Suter LG, Drye EE, Krumholz HM. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.216476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers WJ, Frederick PD, Stoehr E, Canto JG, Ornato JP, Gibson CM, Pollack CV, Jr, Gore JM, Chandra-Strobos N, Peterson ED, French WJ. Trends in presenting characteristics and hospital mortality among patients with ST elevation and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J. 2008;156(6):1026–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hess CN, Shah BR, Peng SA, Thomas L, Roe MT, Peterson ED. Association of early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission after non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction among older patients. Circulation. 2013;128(11):1206–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yost G, Puher SL, Graham J, Scott TD, Skelding KA, Berger PB, Blankenship JC. Readmission in the 30 Days after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC-Cardiovascular Interventions. 2013;6(3):237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown J, Chang CH, Zhou W, MacKenzie TA, Malenka DJ, Goodman DC. Health System Characteristics and Rates of Readmission after Acute Myocardial Infarction in the United States. JAHA. 2014;3(3):1–9. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunlay S, Pack QR, Thomas RJ, Killian JM, Roger VL. Participation in Cardiac Rehabilitation, Readmissions, and Death after Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am J Med. 2014;127(6):538–546. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edmondson D, Green P, Ye S, Halazun HJ, Davidson KW. Psychological Stress and 30-Day All-Cause Hospital Readmission in Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients: An Observational Cohort Study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e91477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]