Abstract

Background

The incidence of adverse tracheal intubation associated events (TIAEs) and associated patient, practice, and intubator characteristics in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) setting are unknown.

Objectives

To determine the incidence of adverse TIAEs and to identify factors associated with TIAEs in the NICU.

Methods

Single-site prospective observational cohort study of infants who were intubated in a level 4 referral NICU between 9/1/2011–11/30/2013. A standardized pediatric airway registry was implemented to document patient, practice, and intubator characteristics and outcomes of intubation encounters. The primary outcome was adverse TIAEs.

Results

Adverse TIAEs occurred in 153 of 701 (22%) TI encounters. Factors that were independently associated with lower incidence of TIAEs in logistic regression included attending physician (versus resident) (Odds Ratio [OR] 0.4, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.16, 0.98) and use of paralytic medication (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.25, 0.81). Severe oxygen desaturations (≥20% decrease in oxygen saturation) occurred in 51.1% of encounters and were more common in TIs performed by residents (62.8%), compared to fellows (43.2%) or attendings (47.5%) (p=0.008).

Conclusions

Adverse TIAEs and severe oxygen desaturation events are common in the NICU setting. Modifiable risk factors associated with TIAEs identified include intubator training level and use of paralytic medications.

Keywords: Adverse Events, Intubation, Newborn Resuscitation, Intensive Care, Outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Tracheal intubation (TI) is a life saving but technically challenging procedure, which carries a meaningful risk of morbidity and mortality for critically ill infants and children.[1–4] Medical training level is associated with both success of TI and the incidence of adverse tracheal intubation associated events (TIAEs) in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).[1, 4] In a combined study of neonatal and pediatric patients, TI attempts by inexperienced operators were more likely to result in oxygen desaturation and bradycardic episodes.[5]

Little is known regarding the incidence and characteristics of adverse TIAEs in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The objectives of this study were to characterize the incidence of adverse TIAEs and severe oxygen desaturation during TI and to determine the association of patient, practice and intubator characteristics with adverse TIAEs in a large academic NICU. We hypothesized that intubator training level would be associated with occurrence of adverse TIAEs and severe desaturation events during TI, and that modifiable factors associated with TIAEs could be identified.

METHODS

Setting

This was a prospective observational cohort study at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia NICU, an 85-bed level 4, referral NICU.

Patient selection

All infants who underwent TIs with direct laryngoscopy between September 1, 2011 and November 30, 2013 in the NICU were identified for potential inclusion. Neonatal TIs performed outside the NICU were excluded. Intubations in the hospital’s small referral delivery unit were excluded, as this delivery unit has only 300–400 specialized deliveries a year and has a separate staffing model. This study was performed within a convenience sample derived during the study period.

Data Collection and Definitions

A previously developed TI data collection tool, the National Emergency Airway Registry for Children (NEAR4KIDS), was used in the NICU.[6] Greater than 95% compliance with data capture and accuracy were established. A respiratory therapist and intubator completed the data collection form after every intubation. A research assistant checked all data forms for completeness, interviewed participating clinicians for missing data when needed, and entered de-identified data into a secure web-based database.

Briefly, operational definitions are as follows: ‘Course’ was defined as one method to intubate (i.e., oral or nasal) and one set of medications. We only included intubation encounters with one course in this analysis; many attempts could occur within this course. First attempt success was defined as successful intubation on the first attempt. Overall success was defined as successful intubation by the initial intubator.

Patient demographics were abstracted from the medical record. Weight was recorded on the day of TI, not birth weight. A “history of difficult airway” was reported based on any known prior history of difficulty managing the patient’s airway. Intubator background and training level were recorded for every attempt; training level of the initial intubator was used in analysis. Medications were used according to the clinical team’s preference and were classified as “sedative/narcotic” (including opiates, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates) or “paralytic” (including depolarizing or non-depolarizing neuromuscular blockade).

Adverse events

Adverse events were classified into two categories: severe TIAEs and non-severe TIAEs. Severe TIAEs included cardiac arrest, esophageal intubation with delayed recognition, emesis with witnessed aspiration, hypotension requiring intervention (fluid and/or vasopressors), laryngospasm, malignant hyperthermia, pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum, or direct airway injury. Cardiac arrest was defined as loss of perfusion or severe bradycardia requiring chest compressions for ≥1 minute.

Non-severe TIAEs included mainstem bronchial intubation, esophageal intubation with immediate recognition, emesis without aspiration, hypertension requiring therapy, epistaxis, lip trauma, gum or oral trauma, medication error, dysrhythmia, and pain and/or agitation requiring additional medication and causing delay in intubation. Mainstem bronchial intubation was considered only when it was confirmed on chest radiograph or recognized after the clinical team secured the tracheal tube. Dysrhythmia included bradycardia requiring chest compressions for <1 minute or arrhythmia requiring treatment.

The highest pulse oximetry saturation (SpO2) measured prior to intubation (i.e., during pre-oxygenation) and the lowest measured SpO2 during the intubation encounter were recorded. Oxygen desaturation was calculated as the difference between these values. The same method was used for infants with cyanotic heart disease, as the relative difference between initial SpO2 and lowest SpO2 was used for analysis. If either the initial or lowest saturation was not reliably measured (i.e., from a poor waveform), oxygen saturation data were not included in analysis. We defined an a priori dichotomous variable for severe desaturation as ≥20% decrease in SpO2.

Intubation Guidelines

Although our NICU does not have a written protocol for intubation procedures, the general guidelines are: the number of attempts is limited to two per intubator; during non-emergent conditions, infants are stabilized with bag mask ventilation between attempts until heart rate and oxygen saturations recover to pre-procedural levels; and there is no time limit for intubation attempts.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Summary statistics were described with mean and standard deviation (SD) for parametric variables and median with interquartile range (IQR) for nonparametric variables. Categorical variables were compared between TI encounters with and without TIAEs using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for comparison of nonparametric variables.

We developed a logistic regression model for the TIs performed by residents, attendings, and fellows in order to examine the independent association between medical training level and TIAEs. TIs performed by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, staff NICU pediatricians, and non-neonatal physicians were excluded from the model, as experience level for these providers was not recorded in the database. The model included the patient and practice characteristics associated w ith TIAEs in univariate analysis (p<0.1) and patient characteristics that were hypothesized a priori to increase the risk of TIAEs: small patient size (<2 kilograms)[5] and history of difficult1 airway.[1]

Median severity of oxygen desaturation was summarized for all encounters. Frequency of severe desaturation events was compared between intubator levels using χ2 test. Initial oxygen saturation level and degree of oxygen desaturation was compared between encounters with and without TIAE using Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Ethics Board Approval

The local Institutional Review Board approved this study, and informed consent was waived.

RESULTS

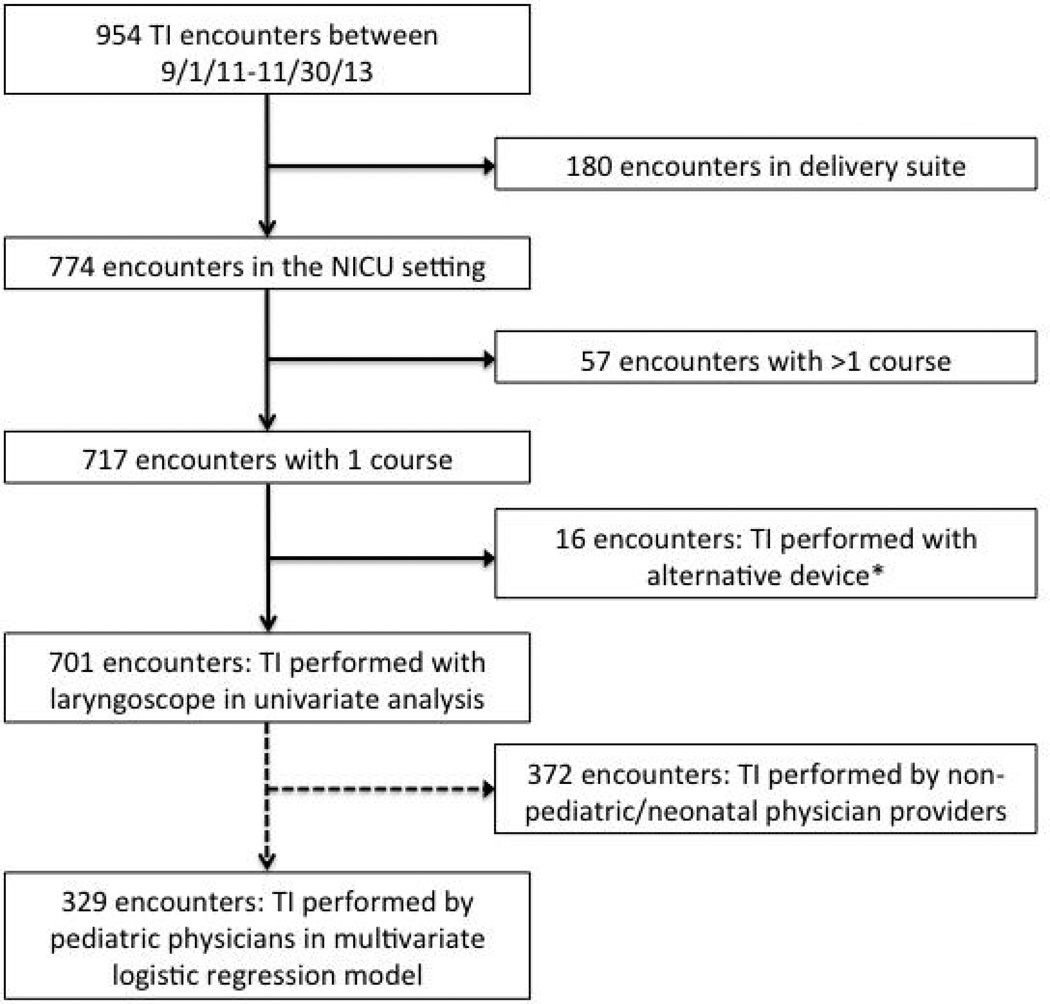

There were 701 intubation encounters analyzed (Figure 1). The median number of attempts for each was 2 (IQ range 1, 3). At least 1 TIAE was reported in 153 (22%) encounters. Severe TIAEs occurred in 26 (3.7%), and non-severe TIAEs occurred in 133 (19.0%). Severe oxygen desaturation (≥20% decrease in SpO2) occurred in 51.1% of encounters with available SpO2 data (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Tracheal intubation (TI) encounters included in analysis

*Includes laryngeal mask airway (LMA) and fiber optic flexible laryngoscope

Table 1.

Incidence of adverse TIAEs during tracheal intubation encounters

| Encounters with TIAE, n (%) (n=701) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Severe TIAE | 26 (3.7%) | |

| Esophageal intubation-delayed recognition | 14 (2%) | |

| Cardiac arrest-patient survived | 6 (0.9%) | |

| Airway trauma | 2 (0.3%) | |

| Vomit with aspiration | 2 (0.3%) | |

| Laryngospasm | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Hypotension requiring intervention | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Cardiac arrest-patient died | 0 | |

| Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum | 0 | |

| Malignant hyperthermia | 0 | |

| Non-severe TIAEa | 133 (19.0%) | |

| Esophageal intubation-immediate recognition | 104 (14.8%) | |

| Mainstem intubation | 14 (2%) | |

| Vomit without aspiration | 9 (1.3%) | |

| Gum or oral trauma | 9 (1.3%) | |

| Lip trauma | 8 (1.1%) | |

| Pain or agitation delaying intubation | 5 (0.7%) | |

| Dysrhythmia | 4 (0.6%) | |

| Medication error | 0 | |

| Epistaxis | 0 | |

| Hypertension requiring intervention | 0 | |

| One or more TIAE (any type)b | 153 (21.8%) | |

| Severe desaturation (≥20% decrease in SpO2) | 341/668 (51.1%) | |

TIAEs- Tracheal Intubation Associated Events.

Non-severe TIAE: 117 encounters with 1 Non-severe TIAE, 13 encounters with 2 Non-severe TIAEs, 2 encounter with 3 Non-severe TIAEs, 1 encounter with 4 Non-severe TIAEs.

All TIAE: 132 encounters with 1 TIAE, 17 encounters with 2 TIAEs, 3 encounters with 3 TIAEs, 1 encounter with 4 TIAEs

Patient and practice factors associated with TIAEs

Characteristics such as age, weight, sex, and history of difficult airway did not significantly differ between patients with TIAEs and without TIAEs (Table 2). In univariate analysis, ventilation failure (i.e., rising CO2) was the indication for TI more frequently in encounters with TIAEs than without TIAEs (38.6% vs. 24.8%, p=0.001). Conversely, endotracheal tube replacement (rather than primary intubation) was less frequently the indication for encounters with TIAEs than without TIAEs (15.7% vs. 27.9%, p=0.002).

Table 2.

Patient and practice characteristics of tracheal intubation encounters with and without TIAE

| Variable | TIAE (n=153) | No TIAE (n=548) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age in months, median (IQR) | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | 0.67 | |

| Patient weight | 0.27 | |||

| <1500g | 30 (19.6%) | 81 (14.8%) | ||

| 1500–1999g | 15 (9.8%) | 46 (8.4%) | ||

| ≥2000g | 108 (70.6%) | 421 (76.8%) | ||

| Male sex | 86 (56.2%) | 276 (50.4%) | 0.20 | |

| History of difficult airway | 29 (19.0%) | 96 (17.5%) | 0.68 | |

| Indicationa | ||||

| Elective primary intubation | 15 (9.8%) | 58 (10.6%) | 0.78 | |

| Oxygen failure | 29 (19.0%) | 76 (13.9%) | 0.12 | |

| Ventilation failure | 59 (38.6%) | 136 (24.8%) | 0.001 | |

| Apnea | 18 (11.8%) | 49 (8.9%) | 0.29 | |

| Upper airway obstruction | 4 (2.6%) | 25 (4.6%) | 0.36b | |

| Reintubation after unplanned extubation | 7 (4.6%) | 44 (8.0%) | 0.15 | |

| Replace endotracheal tube | 24 (15.7%) | 153 (27.9%) | 0.002 | |

| Nasal intubation | 4 (2.6%) | 25 (4.6%) | 0.36b | |

| Sedative/narcotic medications | 134 (87.6%) | 469 (85.6%) | 0.53 | |

| Paralytic medications | 100 (65.4%) | 408 (74.5%) | 0.026 | |

TIAE- tracheal intubation associated event, IQR- interquartile range.

More than one indication may be present per encounter. Indication not recorded in 34 (4.9%) encounters

Fisher’s exact test

The most frequently used medications were fentanyl (91.0%) and morphine (7.0%). Sedative/narcotic pre-medication use did not significantly differ between encounters with and without TIAEs (87.6% vs. 85.6%, p=0.53). Paralytic medications were used less frequently in encounters with TIAEs than without TIAEs (65.4% vs. 74.5%, p=0.026).

Intubator characteristics associated with TIAEs

Initial intubators were pediatric residents in 15.1% of encounters (first attempt success rate 26.4%), neonatology fellows in 23.1% of encounters (first attempt success rate 50%), and neonatology attendings in 8.7% of encounters (first attempt success rate 62.3%). The remaining intubators were other neonatal clinicians (43.9%) and physicians from other disciplines (9.1%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Intubator characteristics for TI encounters (n=701)

| Intubator | Performed First Attempt |

Performed Second Attempt |

Performed Third Attempt |

First Attempt Success |

Overall Successa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident, general pediatrics | 106 (15.1%) | 41 (10.8%) | 7 (3.1%) | 28/106 (26.4%) | 34/106 (32.1%) |

| NICU fellow | 162 (23.1%) | 104 (27.4%) | 82 (36.4%) | 81/162 (50%) | 113/162 (69.8%) |

| NICU attending | 61 (8.7%) | 56 (14.7%) | 64 (28.4%) | 38/61 (62.3%) | 53/61 (86.9%) |

| NICU non-physician clinicianb | 308 (43.9%) | 142 (37.4%) | 36 (16.0%) | 132/308 (42.9%) | 190/308 (61.7%) |

| Non-NICU physicianc | 64 (9.1%) | 37 (9.7%) | 36 (16.0%) | 42/64 (65.6%) | 53/64 (82.8%) |

| Total | 701 | 380 | 225 | 321/701 (45.8%) | 443/701 (63.2%) |

Success by first intubator within 5 attempts

Includes NICU nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and staff pediatricians

Includes physicians from Otolaryngology, Anesthesiology, and General Surgery

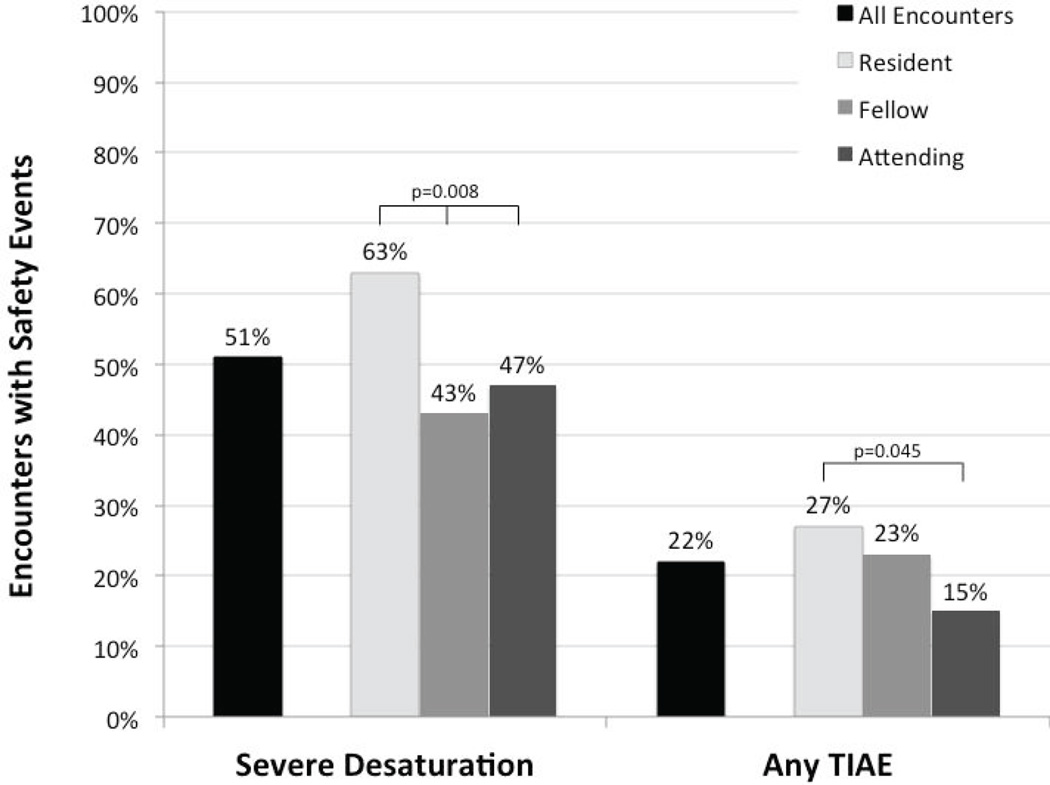

TIAEs occurred more frequently during TIs performed by residents (27.4%) and fellows (22.8%) compared with attendings (14.8%) (Figure 2). This was not statistically significant in univariate analysis. In the logistic regression model of TIs performed by pediatric/neonatal physicians, the only significant factors associated with decreased risk of TIAEs were attending-level intubator (Odds Ratio [OR] 0.40, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.16, 0.98 compared to resident) and paralytic medications use (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.25, 0.81) (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Bar graph demonstrating proportion of tracheal intubation encounters with severe desaturation (≥20% decrease in SpO2) and any tracheal intubation associated event (TIAE). Results are shown for all encounters and separated by intubator training level.

Desaturations: p=0.008, χ2 (2 d.f.)

TIAE: p=0.045, attending (vs. resident) in multivariate logistic regression model including: training level, paralytic medications, small patient size, indication of ventilation failure, replacement of endotracheal tube, and history of difficulty airway

Table 4.

Logistic Regression of characteristics associated with TIAEs, includes encounters with TI performed by residents/fellows/attendings (n=329)

| TIAE, Odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted P value |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| First intubator | |||

| Resident (reference) | - | - | |

| Fellow (compared to resident) | 0.81 (0.44, 1.48) | 0.49 | |

| Attending (compared to resident) | 0.40 (0.16, 0.98) | 0.045 | |

| History of difficult airway | 1.33 (0.66, 2.68) | 0.42 | |

| Paralytic medications | 0.45 (0.25, 0.81) | 0.008 | |

| Patient weight<2kg | 1.13 (0.60, 2.11) | 0.71 | |

| Change endotracheal tube | 0.66 (0.32, 1.36) | 0.26 | |

| Ventilation failure | 1.72 (0.93, 3.18) | 0.08 | |

Logistic Regression Pseudo R2=0.053, p=0.009, d.f.=7

TIAEs-tracheal intubation associated events.

Oxygen desaturation

Pulse oximetry data were available in 668 (95.3%) encounters. The median pre-intubation saturation was 100% (IQ range 98%, 100%) for all encounters and did not significantly differ between encounters with and without TIAEs (p=0.22). The median decrease in SpO2 was 20% (IQR 5%, 39%) and was significantly greater when TIAEs occurred (40% versus 15%, p<0.001). Severe oxygen desaturation events (≥20% decrease in SpO2) occurred in 51.1% of encounters. The median pre-intubation saturation was 100% for resident, fellow, and attending intubators. Severe desaturation was more likely to occur with resident intubators (62.8%) compared to fellow (43.2%) or attending intubators (47.5%), p=0.008 (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Our prospective cohort study characterized the incidence of TIAEs and severe oxygen desaturation during TI in the NICU. TIAEs occurred in 22% and severe desaturations occurred in 51% of all TI encounters. Attending-level intubator (versus resident) and use of paralytics were independently associated with significantly fewer TIAEs. Severe oxygen desaturations were more frequent in TIs performed by residents. The median decrease in SpO2 was significantly greater in TIs with TIAEs compared with TIs without TIAEs, suggesting that TIAEs have a meaningful clinical impact.

No previous studies have reported on an inclusive list of TIAEs in NICU patients. Our results are similar to a study of TIAEs in 15 pediatric intensive care units using the NEAR4KIDS airway registry:[4] TIAEs occurred in 21% of TI encounters in that study, and esophageal intubation with immediate recognition was the most commonly reported TIAE. Consistent with our study results in the neonatal ICU, those authors also demonstrated an independent association between intubator training level and TIAEs in the pediatric ICU.

Small published reports of TI safety in the NICU setting have suggested that deterioration in oxygen saturation and heart rate are common.[3, 5, 7] Venkatesh et al. prospectively collected data for 93 TI encounters performed in 3 NICUs. The median lowest recorded SpO2 was 65% in those encounters, and 21% of infants experienced a heart rate of <60 beats/minute during TI.[3] Using video review of 60 attempted TIs in the delivery room, O'Donnell et al. found that ≥10% deterioration in SpO2 and/or heart rate occurred in 49% of intubation encounters.[7] Simon et al. performed a combined multi-site study of TI in NICUs and PICUs. Oxygen desaturation (absolute SpO2 < 90%) and/or bradycardia (heart rate <100 beats/minute) occurred in 23.6% of the neonates included in their study; these events were significantly more likely to occur when TI was performed by intubators with <10 prior airway experiences.[5] In our study, the SpO2 declined by ≥20% in over half of TI encounters, and severe oxygen desaturations were more frequently observed with resident airway providers. However, bradycardia was only recorded when heart rate was <60 beats/minute, limiting our ability to compare the incidence of bradycardia with previously published studies.

More frequent TIAEs and more severe oxygen desaturations during TIs performed by residents may be due to lack of proficiency in endotracheal intubation. Previous studies have demonstrated that less experience is associated with increased duration of intubation attempts and decreased TI success rates.[7–11] Pediatric residents in our study were only successful in 26% of their first TI attempts. Poor resident performance in TI, both in terms of safety and success, may be partly due to the fact that opportunities to perform neonatal intubation have declined. Potential explanations for this trend include changes to the neonatal resuscitation program (NRP), which no longer recommends routine intubation and tracheal suctioning of vigorous meconium-stained newborns,[12] and increased use of non-invasive respiratory support in preterm infants.[13, 14] Reductions in residency training work hours further limit the number of procedural opportunities for pediatric residents.[15]

One important finding in this study was the association of paralytic medication use with fewer TIAEs. We found that the use of paralytic medications use was significantly less common in encounters with any TIAEs and also in encounters with severe TIAEs, similar to data from critically ill adults.[16] The high prevalence of sedative/narcotic use suggests that there was enough time in the majority of TI encounters to prepare and administer pre-medications. Although pre-medication use is recommended for non-emergent neonatal intubation,[17] no single pre-medication regimen has been demonstrated to have clear superiority in improving the safety of neonatal intubation over others. The use and selection of pre-medications for non-emergent neonatal intubation remains variable in practice.[18–20] Studies of neuromuscular blockade for intubation in neonates have largely focused on outcomes related to physiologic variables or intubation success.[21–25] Our results suggest that paralytic medication use is associated with fewer TIAEs in the NICU, providing data to hypothesize that paralytic use improves the safety of TI in the NICU.

This study has several limitations. TIAEs were identified by self-report from the clinical team; this might have underestimated the true incidence of TIAEs. This single site study was performed in a large referral NICU with complex medical and surgical patients and may not generalize to other NICUs or the delivery room setting. Intubators’ years of experience or previous intubation exposures were not recorded in this dataset. We excluded non-physician clinicians from our logistic model because years of experience/training level ranges widely within this group, but this information was not available in this dataset. Lastly, certain patient characteristics, such as age in days or weeks, gestational age, and numerical heart rate, were not recorded. Development of a multi-center neonatal-specific airway registry is underway to address these limitations.

CONCLUSIONS

Adverse tracheal intubation associated events (22%) and severe desaturation events during tracheal intuation (51%) are common in the neonatal ICU setting. These adverse events occur more frequently in TIs performed by resident physicians, compared with fellow or attending physicians. Potentially modifiable risk factors associated with TIAEs include intubator training level and use of paralytic medications.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

EF received funding support from NIH 5T32HD060550-03; VN is supported through Endowed Chair, Critical Care Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; AN received support from AHRQ R03HS021583.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nishisaki A, Turner DA, Brown CA, Walls RM, Nadkarni VM for the National Emergency Airway Registry for Children (NEAR4KIDS) and Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. A national emergency airway registry for children: Landscape of tracheal intubation in 15 PICUs. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:874–885. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182746736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll CL, Spinella PC, Corsi JM, Stoltz P, Zucker AR. Emergent endotracheal intubations in children: Be careful if it's late when you intubate. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venkatesh V, Ponnusamy V, Anandaraj J, Chaudhary R, Malviya M, Clarke P, Arasu A, Curley A. Endotracheal intubation in a neonatal population remains associated with a high risk of adverse events. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:223–227. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders RC, Giuliano JS, Sullivan JE, Brown CA, Walls RM, Nadkarni V, Nishisaki A for the National Emergency Airway Registry for Children Investigators and Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators Network. Level of trainee and tracheal intubation outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e821–e828. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon L, Trifa M, Mokhtari M, Hamza J, Treluyer J-M. Premedication for tracheal intubation: A prospective survey in 75 neonatal and pediatric intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:565–568. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000108883.58081.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishisaki A, Ferry S, Colborn S, DeFalco C, Dominguez T, Brown CA, Helfaer MA, Berg RA, Walls RM, Nadkarni VM for the National Emergency Airway Registry (NEAR) and National Emergency Airway Registry for kids (NEAR4KIDS) Investigators. Characterization of tracheal intubation process of care and safety outcomes in a tertiary pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:e5–e10. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181fe472d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Donnell CPF, Kamlin COF, Davis PG, Morley CJ. Endotracheal intubation attempts during neonatal resuscitation: Success rates, duration, and adverse effects. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e16–e21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leone TA, Rich W, Finer NN. Neonatal intubation: Success of pediatric trainees. J Pediatr. 2005;146:638–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haubner LY, Barry JS, Johnston LC, Soghier L, Tatum PM, Kessler D, Downes K, Auerbach M. Neonatal intubation performance: Room for improvement in tertiary neonatal intensive care units. Resuscitation. 2013;84:1359–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falck AJ, Escobedo MB, Baillargeon JG, Villard LG, Gunkel JH. Proficiency of pediatric residents in performing neonatal endotracheal intubation. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1242–1247. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bismilla Z, Finan E, McNamara PJ, LeBlanc V, Jefferies A, Whyte H. Failure of pediatric and neonatal trainees to meet Canadian neonatal resuscitation program standards for neonatal intubation. J Perinatol. 2010;30:182–187. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, Aziz K, Colby C, Fairchild K, Gallagher J, Hazinski MF, Halamek LP, Kumar P, Little G, McGowan JE, Nightengale B, Ramirez MM, Ringer S, Simon WM, Weiner GM, Wyckoff M, Zaichkin J. Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1400–e1413. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2972E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polin RA, Carlo WA Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Respiratory support in preterm infants at birth. Pediatrics. 2014;133:171–174. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sweet DG, Carnielli V, Greisen G, Hallman M, Ozek E, Plavka R, Saugstad OD, Simeoni U, Speer CP, Vento M, Halliday HL. European consensus guidelines on the management of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome in preterm infants- 2013 update. Neonatology. 2013;103:353–368. doi: 10.1159/000349928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gozzo YF, Cummings CL, Chapman RL, Bizzarro MJ, Mercurio MR. Who is performing medical procedures in the neonatal intensive care unit? J Perinatol. 2011;31:206–211. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilcox SR, Bittner EA, Elmer J, Seigel TA, Nguyen NTP, Dhillon A, Eikermann M, Schmidt U. Neuromuscular blocking agent administration for emergent tracheal intubation is associated with decreased prevalence of procedure-related complications. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1808–1813. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e0e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar P, Denson SE, Mancuso TJ Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. Premedication for nonemergency endotracheal intubation in the neonate. Pediatrics. 2010;125:608–615. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durrmeyer X, Daoud P, Decobert F, Boileau P, Renolleau S, Zana-Taieb E, Saizou C, Lapillonne A, Granier M, Durand P, Lenclen R, Coursol A, Nicloux M, de Saint Blanquat L, Shankland R, Boëlle P-Y, Carbajal R. Premedication for neonatal endotracheal intubation: Results from the epidemiology of procedural pain in neonates study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:e169–e175. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182720616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wheeler B, Broadbent R, Reith D. Premedication for neonatal intubation in Australia and New Zealand: A survey of current practice. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48:997–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2012.02589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhary R, Chonat S, Gowda H, Clarke P, Curley A. Use of premedication for intubation in tertiary neonatal units in the United Kingdom. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:653–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly MA, Finer NN. Nasotracheal intubation in the neonate: Physiologic responses and effects of atropine and pancuronium. J Pediatr. 1984;105:303–309. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrington KJ, Finer NN, Etches PC. Succinylcholine and atropine for premedication of the newborn infant before nasotracheal intubation: A randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:1293–1296. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norman E, Wikström S, Hellstrom-Westas L, Turpeinen U, Hämäläinen E, Fellman V. Rapid sequence induction is superior to morphine for intubation of preterm infants: A randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2011;159:893–899.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le CN, Garey DM, Leone TA, Goodmar JK, Rich W, Finer NN. Impact of premedication on neonatal intubations by pediatric and neonatal trainees. J Perinatol. 2014;34:458–460. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts KD, Leone TA, Edwards WH, Rich WD, Finer NN. Premedication for nonemergent neonatal intubations: A randomized, controlled trial comparing atropine and fentanyl to atropine, fentanyl, and mivacurium. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1583–1591. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]