Abstract

Biomarkers based on germline DNA variations could have translational implications by identifying prognostic factors and sub-classifying patients to tailored, patient-specific treatment. To investigate the association between germline variations in interleukin (IL) genes and lung cancer outcomes, we genotyped 251 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from 33 different IL genes in 651 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Analyses were performed to investigate overall survival, disease-free survival, and recurrence. Our analyses revealed 24 different IL SNPs significantly associated with one or more of the lung cancer outcomes of interest. The GG genotype of IL16:rs7170924 was significantly associated with disease-free survival (HR = 0.65; 95% CI 0.50 – 0.83) and was the only SNP that produced a false discovery rate (FDR) of modest confidence that the association is unlikely to represent a false-positive result (FDR = 0.142). Classification and regression tree (CART) analyses were used to identify potential higher-order interactions. We restricted the CART analyses to the five SNPs that were significantly associated with multiple endpoints (IL1A:rs1800587, IL1B:rs1143634, IL8:s12506479, IL12A:rs662959, and IL13:rs1881457) and IL16:rs7170924 which had the lowest FDR. CART analyses did not yield a tree structure for overall survival; separate CART tree structures were identified for recurrence, based on three SNPs (IL13:rs1881457, IL1B:rs1143634, and IL12A:rs662959), and for disease-free survival, based on two SNPs (IL12A:rs662959 and IL16:rs7170924), which may suggest that these candidate IL SNPs have a specific impact on lung cancer progression and recurrence. These data suggests that germline variations in IL genes are associated with clinical outcomes in NSCLC patients.

Introduction

In the United States, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death among men and women. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represents more than 80% of lung cancer diagnoses and has an overall 5-year survival rate of approximately 16% that decreases precipitously among patients diagnosed with late stage disease [1]. Although pathologic staging is an important prognostic factor for lung cancer [2], there is marked variability in recurrence and survival among patients with the same stage of disease which suggests other factors contribute to NSCLC prognosis. Presently there are few validated biomarkers that can predict patient outcomes for NSCLC and most are based on tumor markers [3,4]. Thus, discovery of biomarkers based on germline DNA variations represent a potential valuable complementary strategy which could have translational implications for predicting patient outcomes and sub-classifying patients to tailored, patient-specific treatment.

Although inflammation by innate immune cells is a physiologic process to fight infections and heal wounds, chronic inflammation can result in sustained tissue damage and cellular proliferation and subsequently lead to metaplasia and dysplasia [5]. As such, inflammation is a “hallmark of cancer” [6] and is evident at the earliest stages of neoplastic development and has a prominent role in enhancing tumorigenesis and cancer progression [7]. Interleukins (ILs) are a diverse family of cytokine molecules that play a regulatory role in the growth, differentiation, and activation of immune cells [8]. Cytokine signaling contributes to tumor progression by stimulating angiogenesis, cell growth, and differentiation and through the inhibition of apoptosis of altered cells at the site of inflammation [9]. Because of their diverse and pleiotropic effects, interindividual differences of ILs are an attractive target to assess for lung cancer outcomes. To date there have been four genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [10-13] that assessed germline variants on NSCLC survival, but none of these GWAS found concordant results. At present, there are few published pathway-based studies on the association between germline variations in IL genes and lung cancer outcomes. To investigate the association between IL genetic polymorphisms and lung cancer outcomes, we genotyped 251 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from 33 different IL genes in 651 NSCLC patients.

Material and Methods

Study population

This analysis included NSCLC patients recruited for H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute’s Total Cancer Care™ (TCC) protocol [14]. TCC is a multi-institutional observational study of cancer patients that prospectively collects self-reported demographic data, clinical data, medical record information, and blood samples for research purposes. There are no exclusion or inclusion criteria to provide consent; patients are followed for life and every patient is eligible. The lung cancer patients in this analysis consented to the TCC protocol at the Moffitt Cancer Center between April 2006 and August 2011 and had a blood sample available for genetic analysis. This research was approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

Cancer registry data

Moffitt’s Cancer Registry abstracts information from patient electronic medical records on demographics, history of smoking, stage, histology, and treatment. Patients seen for second opinions are not included in the Cancer Registry database because they do not fall under current reportable state and/or federal guidelines. Follow-up for vital status, cancer recurrence, and progression occurs annually through active (i.e., chart review and directly contacting the patient, relatives, and other medical providers) and passive methods (i.e., matching mortality records to patients’ names, gender, and addresses). Where available pathologic TNM staging was utilized and if these data were missing we utilized clinical TNM staging. Smoking status was categorized as self-report current-, former-, or never smoker. The Cancer Registry defines “first course of treatment” as all methods of treatment recorded in the treatment plan and administered to the patient before disease progression or recurrence. To determine the impact of treatment, we assessed stage I to III patients who only had surgery versus patients who had surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. Adjuvant chemotherapy was defined as having any chemotherapy regime within 3 months following surgery. Stage IV patients were not included in these analyses since they rarely have surgery because they have metastasis disease by definition.

Blood collection and genotyping

A 10-ml peripheral blood sample was drawn into coded heparinized tubes and genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit and a robotic system following the manufacturer instructions (QIAGen, Valencia, CA). The genotype data for this analysis were from a candidate gene study designed to assess the association between germline genetics and NSCLC patient outcomes. The genes and/or specific SNPs were identified from published data, public databases, and from Illumina’s (San Diego, CA) online Assay Design Tool (ADT) database. We identified 33 candidate IL genes and selected coding and non-coding SNPs in these genes based on one or more of the following criteria: biological plausibility (i.e., specific SNPs shown to have putative or established role in lung cancer), genotype-phenotype relationships (priority was given to SNPs with demonstrated functional significance by in vitro studies or predictive functional significance by in silico data), and polymorphism frequency (SNPs with a demonstrated or estimated allele frequency of less than 5% were excluded). Genotyping was performed at the University of Miami Center-Genome Technology Genotyping Core (Miami, FL) using Illumina’s GoldenGate Assay and iScan platform and the genotypes were called using the BeadStudio software. Concordance among the 3 genomic experimental DNA control samples present in duplicate was 100%. The original SNP list consisted of 257 IL SNPs; however, 6 SNPs were not included in this analysis because one SNP was monomorphic and 5 SNPs had a MAF of < 0.05. The remaining 251 SNPs had a call rate of ≥ 90% for the 651 NSCLC patients.

IL SNPs in silico functional prediction

The SNPs of interest in this analysis were used to search for all SNPs in LD ≥ 0.8 using the online resource SNP Annotation and Proxy (SNAP) tool’s proxy search function [15]. Then, the SNPs of interest and identified SNPs were subject to in silico functional predictions and annotations using SNPnexus [16], SNPinfo [17], Polyphen 2 [18], the UCSC Genome Browser [19], and RegulomeDB [20]. The results from these three searches were organized into a MySQL relational database. The complete RegulomeDB [20] dataset was also incorporated into this MySQL database. A Python program (SNPFunc_Retriever.py) was used to extract selected data from each of the databases with the associated SNP information.

Statistical analysis

Multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression was used to evaluate all SNPs under a dominant genetic model for their association with overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), and time-to-recurrence (TTR). OS, DFS, TTR were assessed from date of lung cancer diagnosis to the date of an event or date or last follow-up. For OS an event was defined as death, for DFS an event was defined as death or progression of cancer, and for TTR an event was defined as a lung cancer recurrence. For TTR, death was a censored event. For all analyses, among individuals without an event, censoring occurred at either 5-years or date of last follow-up if less than 5-years.

For each SNP the most frequent homozygote genotype was set as the referent genotype (Hazard Ratio [HR] = 1.00) and adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking, stage, histology, and first course of treatment, where appropriate. We tested SNP genotypes for departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using the default exact tests implemented in PLINK software (version 1.07) [21]. Bootstrap re-sampling was performed at 1,000x for internal validation and the bootstrap estimate of bias was calculated [22]. For each SNP the estimate of bias was divided by the HR to generate the percentage of bias. The false discovery rate (FDR) was utilized to account for multiple testing [23] for each endpoint (OS, DFS, TTR). The prior for a SNP with a FDR ≤ 0.25 is regarded as modest confidence that the association is unlikely to represent a false-positive result and a SNP with a FDR ≤ 0.05 is regarded as high confidence that the association is unlikely to represent a false-positive result.

A classification and regression tree (CART) approach was utilized to explore potential novel SNP combinations. CART is a nonparametric data-mining tool that can segment data into meaningful subgroups and has been adapted for failure time data [24] using the Martingale Residuals of a Cox model to approximate chi-square values for all possible SNP combinations.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 651 lung cancer patients are presented in Table 1. The mean at diagnosis was 64.8 years, 34.9% were over the age of 70, 50.8% were women, 96.6% were White, 31.6% were current smokers, 55.9% of the patients were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma/BAC, and 54.3% were diagnosed with late stage cancer (stages III or IV). The most frequently recorded treatment plan was patients receiving multiple first course treatments (49.5%). Although the BAC histological classification is no longer reported, this subtype is still included in this analysis because since the data were obtained retrospectively and have not yet been reclassified to the new classification strategy [25]. Univariable HRs revealed that males, current smokers, other NSCLC histology, stage, chemotherapy only, and no first course treatment were significantly associated with an increased risk of death.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the non-small cell lung cancer patients

| Characteristic | No. = 651 | uHR (95% CI)3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| Mean (SD) | 64.8 | (10.3) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) |

| Categorical, N (%) | |||

| ≤ 49 | 55 | (8.5) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 50 to 59 | 133 | (20.4) | 0.82 (0.54, 1.24) |

| 60 to 69 | 236 | (36.3) | 0.95 (0.65, 1.39) |

| ≥ 70 | 227 | (34.9) | 0.98 (0.67, 1.43) |

| Sex, N (%) | |||

| Female | 331 | (50.8) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Male | 320 | (49.2) | 1.30 (1.07, 1.60) |

| Race, N (%)1 | |||

| White | 629 | (96.6) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Black and other race | 22 | (3.4) | 1.40 (0.86, 2.29) |

| Smoking status, N (%) | |||

| Never | 56 | (8.6) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Former | 389 | (59.8) | 1.43 (0.95, 2.17) |

| Current | 206 | (31.6) | 1.69 (1.10, 2.59) |

| Histology, N (%) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma and BAC | 364 | (55.9) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 141 | (21.7) | 1.26 (0.98, 1.63) |

| Other NSCLC | 146 | (22.4) | 1.53 (1.20, 1.95) |

| Stage, N (%) | |||

| I | 225 | (34.6) | 1.00 (referent) |

| II | 73 | (11.2) | 1.56 (1.07, 2.29) |

| III | 183 | (28.0) | 2.39 (1.82, 3.14) |

| IV | 170 | (26.2) | 3.12 (2.38, 4.10) |

| First Course of Treatment2, N (%) | |||

| Multiple | 322 | (49.5) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Surgery only | 243 | (37.3) | 0.53 (0.42, 0.67) |

| Chemotherapy only | 65 | (10.0) | 1.78 (1.30, 2.44) |

| Radiation only | 6 | (0.9) | 1.81 (0.74, 4.39) |

| None | 15 | (2.3) | 1.97 (1.10, 3.52) |

Abbreviations: uHR, univariable Hazard Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; SD, standard deviation; BAC, bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer

Bold font indicates a statistically significant HR

96.5% of the patients were self-reported Hispanic/Latino.

First course of treatment includes all methods of treatment recorded in the treatment plan and administered to the patient before disease progression or recurrence.

OS was used as the endpoint to generate the HRs and 95% CIs.

Table 2 presents the 24 IL SNPs that were significantly associated with OS, DFS, and TTR. Our analyses revealed that seven SNPs were significantly associated with OS and following bootstrap resampling, two remained statistically significant (IL8B:rs12506479 and IL13:rs129568;). Twelve were significantly associated with DFS of which six SNPs remained statistically significant following bootstrap resampling (IL16:rs7170924, IL1B:rs1143634, IL12A: rs662959, IL8:rs12506479, IL12A:rs609907, and IL12A:rs485497). Of the ten SNPs that were significantly associated TTR, five remained statistically significant following bootstrap resampling (IL18:rs2043055, IL1R1:rs3917292, IL2:rs2069763, IL1R1:rs3917285, and IL2:rs2069762). The bootstrap bias ranged from 0.03% to 4.63% indicating there was little evidence of bias from the bootstrap resampling. FDR revealed with modest confidence that the association between IL16:rs7170924 (HR = 0.65; 95% CI 0.50 - 0.83; FDR = 0.142) for DFS is unlikely to represent a false-positive. Although only one SNP fell below our FDR threshold (FDR ≤ 0.25), throughout the results and discussion any SNP that was nominally significant (i.e., P < 0.05 and FDR > 0.25) is described as statistically significantly associated with one or more NSCLC endpoint.

Table 2.

Interleukin SNPs associated with overall survival, disease-free survival, and time to recurrence among non-small cell lung cancer patients

| RSID | Gene Symbol |

SNP Location |

Referent Genotype |

Risk Allele |

MAF | mHR (95% CI)1,5 | P- value2 |

Endpoint | Bootstrap |

FDR4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | Bias3 | ||||||||||

| rs12506479 | IL8 | 5UTR | TT | C | 27.2% | 1.35 (1.09, 1.68) | 0.006 | OS | 0.012 | 0.62% | 0.880 |

| rs2834176 | IL10RB | 3UTR | AA | T | 41.1% | 0.78 (0.63, 0.98) | 0.032 | OS | 0.244 | 1.38% | 0.880 |

| rs1143634 | IL1B | exon | CC | T | 21.8% | 0.78 (0.63, 0.98) | 0.033 | OS | 0.064 | 0.58% | 0.880 |

| rs4850994 | IL1R2 | 3UTR | GG | A | 14.8% | 0.78 (0.61, 0.99) | 0.044 | OS | 0.116 | 0.95% | 0.880 |

| rs1800587 | IL1A | 5UTR | CC | T | 29.8% | 0.80 (0.65, 0.99) | 0.045 | OS | 0.184 | 0.57% | 0.880 |

| rs1295683 | IL13 | 3UTR | CC | T | 9.3% | 1.32 (1.00, 1.73) | 0.049 | OS | 0.048 | 1.65% | 0.880 |

| rs12083537 | IL6R | intron | AA | G | 21.4% | 0.80 (0.64, 1.00) | 0.050 | OS | 0.202 | 0.25% | 0.880 |

| rs7170924 | IL16 | intron | GG | T | 23.0% | 0.65 (0.50, 0.83) | 0.001 | DFS | 0.004 | 0.78% | 0.142 |

| rs1143634 | IL1B | exon | CC | T | 21.8% | 0.73 (0.57, 0.93) | 0.011 | DFS | 0.032 | 0.61% | 0.629 |

| rs662959 | IL12A | 5UTR | CC | T | 13.6% | 1.41 (1.08, 1.83) | 0.012 | DFS | 0.018 | 1.39% | 0.629 |

| rs2856836 | IL1A | 3UTR | TT | C | 29.2% | 0.74 (0.58, 0.94) | 0.014 | DFS | 0.090 | 0.03% | 0.629 |

| rs1800587 | IL1A | 5UTR | CC | T | 29.8% | 0.75 (0.59, 0.95) | 0.017 | DFS | 0.106 | 0.08% | 0.629 |

| rs17561 | IL1A | exon | GG | T | 29.2% | 0.76 (0.59, 0.96) | 0.023 | DFS | 0.120 | 0.03% | 0.629 |

| rs12506479 | IL8 | 5UTR | TT | C | 27.2% | 1.29 (1.01, 1.64) | 0.040 | DFS | 0.026 | 1.57% | 0.629 |

| rs609907 | IL12A | 5UTR | TT | C | 26.3% | 1.28 (1.01, 1.63) | 0.042 | DFS | 0.046 | 0.59% | 0.629 |

| rs2243148 | IL12A | 3UTR | TT | C | 27.3% | 1.28 (1.01, 1.64) | 0.044 | DFS | 0.086 | 1.72% | 0.629 |

| rs1881457 | IL13 | 5UTR | AA | C | 18.8% | 1.29 (1.00, 1.66) | 0.049 | DFS | 0.206 | 2.00% | 0.629 |

| rs485497 | IL12A | 3UTR | GG | A | 49.6% | 0.76 (0.58, 1.00) | 0.052 | DFS | 0.002 | 0.19% | 0.629 |

| rs12508955 | IL15 | intron | GG | T | 26.9% | 1.27 (1.00, 1.63) | 0.054 | DFS | 0.078 | 0.71% | 0.629 |

| rs2043055 | IL18 | intron | AA | G | 37.9% | 1.82 (1.23, 2.67) | 0.003 | TTR | 0.042 | 0.86% | 0.616 |

| rs3917292 | IL1R1 | intron | GG | A | 7.0% | 1.69 (1.07, 2.67) | 0.024 | TTR | 0.024 | 4.63% | 0.974 |

| rs2512149 | IL10RA | 3UTR | TT | C | 19.1% | 1.49 (1.04, 2.13) | 0.030 | TTR | 0.066 | 3.34% | 0.974 |

| rs2069763 | IL2 | exon | GG | T | 33.2% | 1.49 (1.03, 2.15) | 0.032 | TTR | 0.008 | 2.01% | 0.974 |

| rs1881457 | IL13 | 5UTR | AA | C | 18.8% | 1.49 (1.03, 2.16) | 0.034 | TTR | 0.200 | 3.97% | 0.974 |

| rs999261 | IL10RB | intron | TT | C | 17.9% | 1.48 (1.03, 2.13) | 0.036 | TTR | 0.262 | 4.11% | 0.974 |

| rs3917285 | IL1R1 | intron | TT | A | 8.5% | 0.58 (0.34, 0.98) | 0.044 | TTR | 0.052 | 4.62% | 0.974 |

| rs662959 | IL12A | 5UTR | CC | T | 13.6% | 1.49 (1.01, 2.19) | 0.045 | TTR | 0.076 | 0.51% | 0.974 |

| rs2069762 | IL2 | 5UTR | TT | G | 29.7% | 0.70 (0.49, 0.99) | 0.046 | TTR | 0.018 | 1.45% | 0.974 |

| rs3917273 | IL1R1 | intron | AA | T | 41.8% | 0.69 (0.48, 1.00) | 0.047 | TTR | 0.060 | 0.46% | 0.974 |

Abbreviations: mHR, multivariable Hazard Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; MAF, minor allele frequency; FDR, false-discovery rate; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; TTR, time to recurrence

Bold p-values are statistically significant (P < 0.05) following bootstrap resampling

Adjusted for age, sex, race, smoking status, stage, histology, and first course treatment.

P-value from the Cox Proportional Hazard model

The percentage of bias represents magnitude of the bias relative to the HR. The estimate of bias was divided by the HR to generate the percentage of bias for each SNP.

The prior for a SNP with a FDR < 0.25 is regarded as modest confidence that the association is unlikely to represent a false-positive result and a SNP with a FDR < 0.05 is regarded as high confidence that the association is unlikely to represent a false-positive result.

The results were consistent when we analyzed the data among self-reported Non-Hispanic Whites only (data not shown)

Table 3 contains the overall and treatment-specific analyses for the five SNPs significantly associated with multiple endpoints and for IL16:rs7170924 which yielded the lowest FDR. None of the SNPs were significantly associated with all three endpoints. The HRs for the rare-allele genotypes for: IL1A:rs1800587 and L1B:rs1143634 were inversely associated with OS and DFS; IL8:rs12506479 were significantly elevated for OS and DFS; IL12A:rs662959 and IL13:rs1881457 were significantly elevated for DFS and TTR.

Table 3.

Main effects and treatment-specific effects of selected interleukin SNPs

| RSID | Gene Symbol |

Role/Function in Cancer (reference) |

Endpoint | Main effects |

By Treatment4 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mHR (95% CI)1 | P-value2 | Surgery | Surgery plus ACT | ||||

| rs1800587 | IL1A | Tumor invasion and angiogenesis (43) |

OS DFS TTR |

0.80 (0.65, 0.99) 0.75 (0.59, 0.95) 0.81 (0.57, 1.15) |

0.045 0.017 0.2373 |

0.94 (0.54, 1.64) 0.78 (0.47, 1.32) 0.59 (0.22, 1.58) |

0.45 (0.27, 0.76)

0.50 (0.32, 0.79) 0.56 (0.31, 1.00) |

| rs1143634 | IL1B | Tumor invasion and angiogenesis (43) |

OS DFS TTR |

0.78 (0.63, 0.98) 0.73 (0.57, 0.93) 0.71 (0.49, 1.02) |

0.033 0.011 0.0653 |

0.69 (0.39, 1.23) 0.59 (0.34, 1.02) 0.30 (0.09, 1.05) |

0.63 (0.37, 1.05) 0.68 (0.44, 1.07) 0.68 (0.38, 1.22) |

| rs12506479 | IL8 | Angiogenesis; cell proliferation and survival (44) |

OS DFS TTR |

1.35 (1.09, 1.68) 1.29 (1.01, 1.64) 1.02 (0.72, 1.46) |

0.006 0.040 0.9023 |

2.01 (1.15, 3.49) 1.87 (1.11, 3.15) 1.42 (0.52, 3.93) |

1.08 (0.65, 1.80) 1.06 (0.68, 1.66) 0.90 (0.50, 1.60) |

| rs662959 | IL12A | Anti-angiogenesis and anti-metastasis (34) |

OS DFS TTR |

1.15 (0.90, 1.48) 1.41 (1.08, 1.83) 1.49 (1.01, 2.19) |

0.2613 0.012 0.045 |

1.79 (0.96, 3.34) 2.03 (1.15, 3.62) 2.42 (0.88, 6.69) |

1.53 (0.88, 2.67) 1.94 (1.20, 3.12) 1.84 (0.99, 3.39) |

| rs1881457 | IL13 | Tumorigenesis, invasion, and metastasis (45) |

OS DFS TTR |

1.10 (0.87, 1.38) 1.29 (1.00, 1.66) 1.49 (1.03, 2.16) |

0.4353 0.049 0.034 |

0.87 (0.48, 1.60) 0.81 (0.45, 1.44) 0.56 (0.15, 2.05) |

1.56 (0.90, 2.68) 1.66 (1.05, 2.63) 2.07 (1.14, 3.77) |

| rs7170924 | IL16 | Tumor progression, angiogenesis (28) |

OS DFS TTR |

0.82 (0.65, 1.02) 0.65 (0.50, 0.83) 0.79 (0.55, 1.13) |

0.080 0.001 0.201 |

0.51 (0.29, 0.90) 0.49 (0.29, 0.84) 0.82 (0.32, 2.09) |

0.71 (0.41, 1.21) 0.60 (0.37, 0.96) 0.69 (0.38, 1.27) |

Abbreviations: mHR, multivariable hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ACT, adjuvant chemotherapy; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; TTR, time to recurrence

Bold font indicates a statistically significant HR

Adjusted for age, gender, race, smoking status, stage, histology, and first course treatment.

P-value from the Cox Proportional Hazard model

Not statistically significantly associated with the endpoint and were not included in Table 2.

Among IA to IIIB patients only

To determine whether these six SNPs had treatment-specific effects, we analyzed IA-IIIB stage patients who had surgery only (N = 176) versus patients who had surgery and any adjuvant chemotherapy (N = 143). There was no evidence of effect modification for IL1A:rs1800587, IL1B:rs1143634, IL12A:rs662959, and IL16:rs7170924 since the point estimates for their treatment-specific effects were in the same direction as their main effects. Conversely, there was evidence of effect modification for IL8:rs12506479 and L13:rs1881457. For IL8:rs12506479, the rare allele genotypes were significantly elevated for OS (HR = 2.01; 95% CI 1.15 – 3.49) and DFS (HR = 1.87; 95% CI 1.01 – 1.64) among patients treated with surgery only and the point estimates were near the null for the patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery. For L13:rs1881457, the rare allele genotypes were significantly elevated for DFS (OR = 1.66; 95% CI 1.05 – 2.63) and TTR (HR = 2.07; 95% CI 1.14 – 3.77) among patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery. However, the point estimates were inversely associated with all three endpoints among the surgery only patients, but they were not statistically significant. Since there were only 143 stage IA–IIIB patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, we were unable to analyze the data by type of chemotherapy.

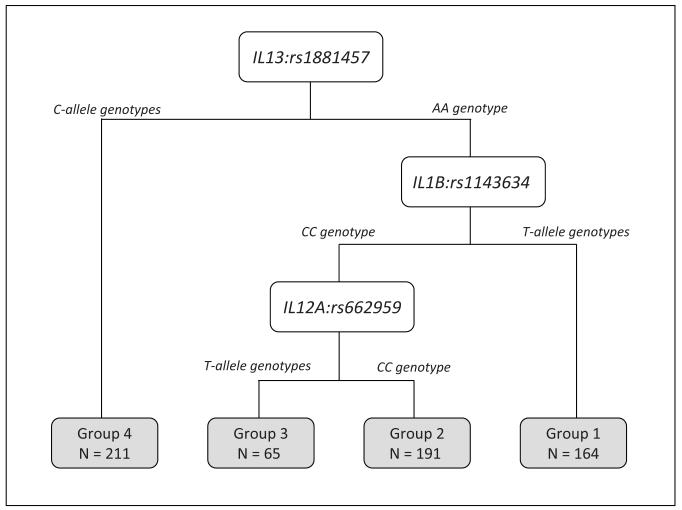

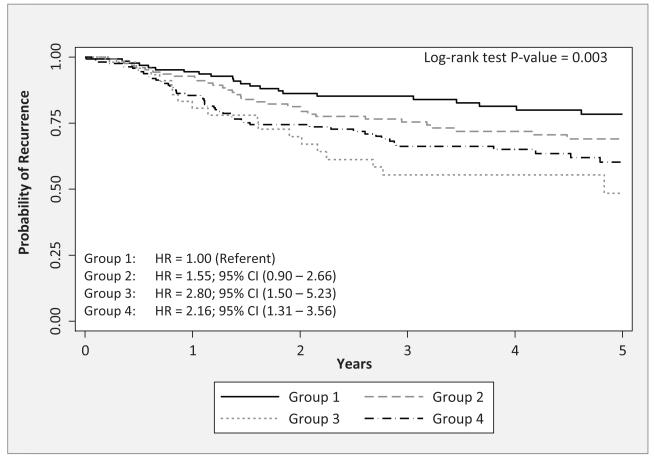

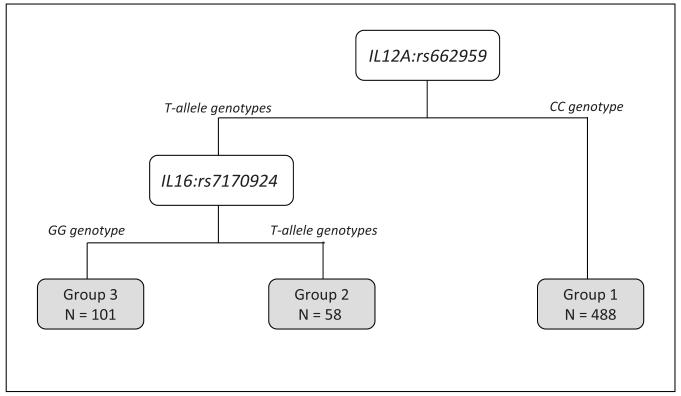

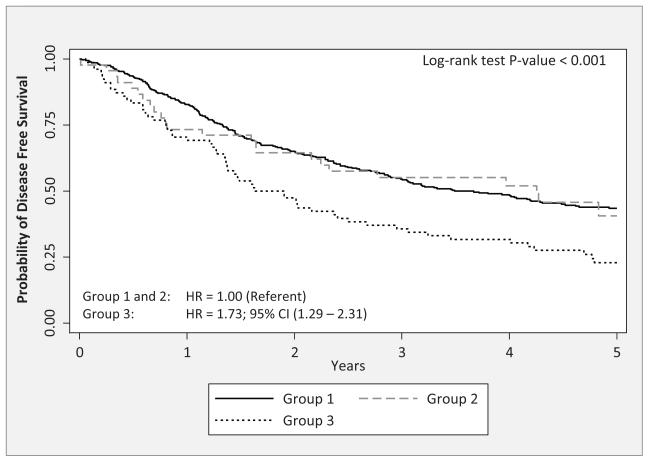

A CART approach was used to identify potential higher-order interactions. We restricted the CART analyses to the SNPs in Table 3 which are the SNPs that were significantly associated with multiple endpoints and IL16:rs7170924 which had the lowest FDR. We found CART tree structure associated with TTR (Figure 1A that had four patient subgroups based on three SNPs (IL13:rs1881457, IL1B:rs1143634, and IL12A:rs662959). The four subgroups were arbitrarily labeled as “Group 1” to “Group 4”. Patients in Group 3, who possessed the common AA genotype for IL13:rs1881457 and the common genotype IL1B:rs1143634 and the T-allele genotypes for IL12A:rs662959, had significantly poorer outcome compared to patients in Group 1 who possessed the common AA genotype for IL13:rs1881457 and the variant T-allele genotypes for IL1B:rs1143634 (P = 0.003). We also found CART tree structure associated with DFS (Figure 2A) that had three patient subgroups based on two SNPs (IL12A:rs662959 and IL16:rs7170924). Patients in Group 3, who possessed the T-allele genotypes for IL12A:rs662959 and the common GG genotype for IL16:rs7170924 exhibited significantly poorer outcome compared to patients in Groups 1 and 2 (Figure 2B; P < 0.001). CART analyses did not yield CART tree structure for OS.

Figure 1.

A) The tree structure of the classification and regression tree (CART) analysis for time-to-recurrence of the six IL SNPs from Table 3. The CART analysis identified 4 subgroups based on three of the six SNPs: IL13:rs1881457, IL1B:rs1143634, and IL12A:rs662959. B) The Kaplan-Meier survival curves and overall log-rank test for the subgroups identified by the CART analysis. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each subgroup using group 1 as the referent subgroup (HR = 1.00).

Figure 2.

A) The tree structure of the classification and regression tree (CART) analysis for disease free survival of the six IL SNPs from Table 3. The CART analysis identified 3 subgroups based on two of the six SNPs: IL12A:rs662959 and IL16:rs7170924. B) The Kaplan-Meier survival curves and overall log-rank test for the subgroups identified by the CART analysis. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for subgroup 3 using groups 1 and 2 as the referent subgroup (HR = 1.00).

The 24 SNPs significantly associated with the lung cancer endpoints in Table 2 were subjected to in silico annotation using SNPnexus [16], SNPinfo [26], Polyphen 2 [18], the UCSC Genome Browser [19], and RegulomeDB [20] (Table 4). The majority of the SNPs analyzed fell in non-coding regions of DNA with the exception of the IL1A:rs17561, IL1B:rs1143634, and IL2:rs2069763. Of the five SNP loci in Table 3, the functional prediction tools revealed which variants had potential impact on splicing (IL1B:rs1143634 and IL1A:rs1800587), transcription factor binding sites (IL1A:rs1800587 and IL1A:rs1881457), or were associated with copy number variants (IL13:rs1881457 and IL12A:rs662959). The highest scoring of SNPs from RegulomeDB was IL13:rs1881457 which is associated with GATA1 transcription factor binding, histone marks, and DNAse sensitivity.

Table 4. Results from the in silico Functional Prediction.

| SNP | Gene Symbol |

Allele | AA Position |

AA Change |

SNP Detail |

Splice Distance |

miRanda | Polyphen 2 | TFBS | CNV (PMID) |

Splicing ESE |

RegulomeDB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs17561 | IL1A | C|A | 114 | A>S | nonsyn | - | - | 0.9282 | - | - | Yes | 3a |

| rs2856836 | IL1A | A|G | - | - | - | - | miR-130; miR-526b |

- | - | - | - | No Data |

| rs3917285 | IL1R1 | T|A | - | - | - | 68 | - | - | - | 21882294 | - | No Data |

| rs3917273 | IL1R1 | A|T | - | - | - | 1515 | - | - | - | 21882294 | - | No Data |

| rs3917292 | IL1R1 | G|A | - | - | - | 311 | - | - | - | 21882294 | - | 4 |

| rs4850994 | IL1R2 | G|A | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 21882294 | - | 5 |

| rs2069763 | IL2 | C|A | 38 | L>L | syn | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | 5 |

| rs2069762 | IL2 | A|C | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | - | - | 5 |

| rs2243148 | IL12A | T|C | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 17160897 | - | No Data |

| rs485497 | IL12A | A|G | - | - | - | 3240 | - | - | - | 17160897 | - | 5 |

| rs12083537 | IL6R | A|G | - | - | - | 2913 | - | - | - | 19592680 | - | 2a |

| rs2512149 | IL10RA | T|C | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 |

| rs999261 | IL10RB | A|G | - | - | - | 2329 | - | - | - | 21882294 | - | 5 |

| rs2834176 | IL10RB | A|T | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20534489 | - | No Data |

| rs609907 | IL12A | A|G | - | - | - | 14108 | - | - | - | 17160897 | - | 6 |

| rs1295683 | IL13 | A|G | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 19592680; 21882294 |

- | 3a |

| rs12508955 | IL15 | T|G | - | - | - | 749 | - | - | - | 21882294 | - | No Data |

| rs7170924 | IL16 | G|T | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6 |

| rs2043055 | IL18 | A|G | - | - | - | 3005 | - | - | - | 23290073; 19592680 |

- | No Data |

| rs18005871 | IL1A | G|A | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | - | Yes | 5 |

| rs11436341 | IL1B | G|A | 105 | F>F | syn | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | 5 |

| rs125064791 | IL8 | T|C | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 |

| rs6629591 | IL12A | C|T | - | - | - | 5653 | - | - | - | 17160897 | - | No Data |

| rs18814571 | IL13 | A|C | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | 19592680 | - | 3a |

Abbreviations: AA, amino acid; syn, synonymous; nonsyn, non-synonymous

SNP locus from Table 2 that was significantly associated with multiple end points.

The Polyphen prediction is ‘probably damaging’

For each gene that contained a significant SNP, we performed a KEGG enrichment analysis of that gene [27] compared to the complete list of ILs using WebGestalt [28]. Modest fold-enrichment values were observed for several pathways (Supplemental Table 1). The most enriched pathway was that of the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway (Fold enrichment = 21.30). This pathway is involved in recognizing pathogens and initiating inflammatory response elements such as expression of interleukin genes [29]. Indeed, mutations in NOD2 can result in increased IL1β production [30] and subsequently affect lung cancer patient outcomes.

Discussion

We investigated germline polymorphisms in IL genes and their associations with multiple NSCLC endpoints. Our analyses revealed 24 different IL SNPs significantly associated with lung cancer endpoints, of which five SNPs were associated with multiple endpoints. Specifically, IL1A:rs1800587, IL1B:rs1143634, and IL8:rs12506479 were significantly associated with OS and DFS, while IL12A:rs662959 and IL13:rs1881457 were significantly associated with DFS and TTR. When we accounted for multiple comparisons, only one SNP (IL16:rs7170924) produced a FDR that the association is unlikely to represent a false-positive result. The GG genotype of IL16:rs7170924 was significantly associated with disease-free survival (HR = 0.65; 95% CI 0.50 – 0.83). CART analyses were used to identify potential higher-order interactions which identified separate CART tree structures for recurrence, based on three SNPs (IL13:rs1881457, IL1B:rs1143634, and IL12A:rs662959), and for disease-free survival, based on two SNPs (IL12A:rs662959 and IL16:rs7170924).

Previous lung cancer association studies have reported IL SNPs associated with pain severity [31], postoperative morbidity [32], radiation-induced toxicity [33], analgesia response [34], recurrence [35], and overall survival [33,35,36]. Although the current analyses revealed 24 different IL SNPs significantly associated with lung cancer endpoints, IL16:rs7170924 was the only SNP that produced an FDR of modest confidence that the association is unlikely to represent a false-positive result. To date, there have been no published data demonstrating a statistically significant association of IL16:rs7170924 on risk or cancer outcomes. IL16 is a pro-angiogenesis cytokine that has the potential to act directly, either in a paracrine or autocrine fashion, to influence tumor cell growth and progression and previous evidence suggests that IL16 may be a potential diagnostic and prognostic factor for several types of solid and hematologic malignancies [37]. Thus, germline variations that attenuate angiogenesis mediated by IL16 could result in improved patient outcomes as revealed in our analyses.

In our study we explored CART analysis because it provides a novel approach to identify potential higher-order interactions to reclassify patients into subgroups that may not otherwise be identified utilizing standard analytical approaches such as Cox regression modeling. The initial split of the CART tree structure for TTR (Figure 1A) was IL13:rs1881457, suggesting that this SNP locus is responsible for the most variation for risk of recurrence. The two subsequent splits were based on IL1B:rs1143634 and IL12A:rs662959 which provided further variation for TTR among patients with the common genotype (AA) for IL13:rs1881457. We also identified a CART tree structure for DFS which yielded 3 patient subgroups based on two SNPs. The initial split of the DFS CART tree structure (Figure 2A) was IL12A:rs662959, which was also found in the CART tree structure for recurrence (Figure 1A). To date, there have been no published data investigating the association of IL12A:rs662959 on cancer risk or outcomes. However, previous association studies have reported significant associations with other IL12 polymorphisms for prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma [38] and risk of lung cancer [39], nasopharyngeal cancer and hepatocellular carcinomas [40], cervical and vulvar cancers [41], and colorectal cancer [42]. IL12 is multifunctional cytokine that interacts with both innate and adaptive immunity, is a key regulator of cell-mediated immune responses, and induces anti-angiogenesis activity mediated by IFN-γ–inducible genes [43]. Thus, germline variations that result in attenuate IL12-mediated angiogenesis could result in increased cancer progression and recurrence as observed in findings. CART analyses did not yield a tree structure for OS, which may suggest that these candidate IL SNPs have a specific impact on lung cancer progression and recurrence.

Treatment-specific analyses were performed to revealed potential effect modification for IL8:rs12506479 and L13:rs1881457. Among patients with rare allele genotypes for IL8:rs12506479, we found significantly elevated points for OS and DFS among the surgery only patients, but the estimates were driven towards the null among patients treated with surgery only. Thus, adjuvant chemotherapy may attenuate the deleterious effects of the common risk for IL8:rs12506479 that was observed among patients treated by only surgical resection. Interestingly, the rare allele genotypes for L13:rs1881457 were significantly elevated for DFS and TTR among patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery while the point estimates were inversely associated with all three endpoints among the surgery only patients. The treatment-specific analyses for IL13:rs1881457 suggest that adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery may be deleterious among patients with the risk rare allele genotypes for IL13:rs188145.

Extensive in silico annotation was performed to determine potential functional significance of all 24 SNPs that were significantly associated with the endpoints. The variant at IL1A:rs17561 was the only non-synonymous SNP and analyses with PolyPhen 2 tool classified its amino acid substitution of alanine to serine (A114S) as “probably damaging” with a score of 0.982. Interestingly, the A114S variant coded by IL1A:rs17561 falls in the recognition domain for Calpain-mediated cleavage that removes the precursor peptide to yield the active IL1A protein. Importantly, Calpain processes the S114 variant 100-fold more effectively than the A114 IL1A protein [44], which may suggest that patients harboring the S114 IL1A protein could produce higher levels of active IL1A and subsequently modulate the inflammatory response. Lee et al. [45] demonstrated that IL1A mRNA expression is independent of the IL1A:rs17561 genotype while release of active IL1A is dependent on genotype. The importance of the IL1A:rs17561 SNP in human disease is exemplified by the 33 association studies including lung cancer response to radiotherapy and increased risk for breast cancer and ovarian cancer (Supplemental Table 2). Among the five SNP loci that were found to be significantly associated with multiple endpoints, in silico annotation revealed that these variants may have potential functional impact on splicing, transcription factor binding sites, and associations with copy number variants (Table 4). RegulomeDB revealed there is a high likelihood of transcriptional regulation at or near IL13:rs1881457 because of its association GATA1 transcription factor binding, histone marks, and DNAse sensitivity. Additionally, ENCODE data for lung cell line specific experiments (Supplemental Figure 1A to E) indicate that IL8:rs12506479 overlaps with several functional features including H3K27 acetylation indicate proximity to active regulatory elements (Supplementary Figure 1E). Additionally, the variant at IL1A:rs1800587 has been previously shown to contribute to an increase in IL1A promoter activity, mRNA levels, and protein levels [46]. Since these 5 SNPs mark regions of functional importance with a causal SNP that is in linkage disequilibrium (LD), SNAP was used to identify SNPs in high LD (r2 > 0.8) and a bioinformatic pipeline identified other SNPs that may have functional impacts on the IL genes. Interestingly, the variant at IL1A:rs17561 was found to be in LD with IL1A:rs1800587 (r2 = 1.0), which was the only non-synonymous coding SNP analyzed from Table 2. However, IL1A:rs1800587 was significantly associated with OS and DFS while IL1A:rs17561 was only significantly associated with DFS. Several of the SNPs (Supplemental Table 3) overlap with functional features, however, tailored functional experiments would be required to determine the exact functional impacts of these SNPs on gene expression and the cellular impacts.

There are some limitations to this analysis that should be noted. Although we evaluated 33 different IL genes and 251 SNPs, this panel is far from comprehensive. However, lack of concordance in the results across the four previous GWAS [10-13] may suggest that a large array of SNPs spanning the entire genome may not be the optimal approach. We also acknowledge the possible lack of generalizability of our study population is derived from a single clinic from a tertiary Cancer Center and is comprised of mostly non-Hispanic Whites. However, state and national cancer registries do not collect tissue for germline DNA, and therefore, efficient recruitment of large numbers of patients is only possible through high-volume clinics, such as Moffitt’s Thoracic Oncology Clinic. Although there is no reason to think that patients treated at Moffitt would differ with respect to IL gene polymorphisms compared to patients treated at other facilities, we must consider that lung cancer patients at a tertiary cancer center like Moffitt could represent more complex cases. Another possible limitation is that the SNPs identified in our analyses might be correlated with other SNPs in the region including the causal variant, but we would require fine-mapping of these IL genes to further isolate additional key markers. Another possible limitation is that we did not include rare variants in our SNP panel since a growing body of evidence suggests that rare SNPs with a minor allele frequency of less than 5% are also an important component of the genetic influence of common human diseases [47]. However, with a sample size of 651 we would have likely been underpowered to detect statistically significant results. Although we performed bootstrap re-sampling to internally validate our findings and noted little evidence of bias from the bootstrap re-sampling, the FDR analyses revealed modest confidence for only one SNP as unlikely to represent a false-positive result.

Although the vivo functional significance of these germline variations needs to be validated in experimental models, these data suggests that germline variations in interleukin genes are associated with clinical outcomes in NSCLC patients. We also revealed a novel and potential high-order interactions of IL SNPs related to recurrence and disease-free survival that has not been demonstrated previously. Validated germline biomarkers, even with small effects, may have potential important clinical implications by optimizing patient-specific treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. ENCODE results for lung cell line experiments for 1A) IL12A:rs662959, 1B) IL1B:rs1143634, 1C), IL1A:rs1800587, 1D) IL13:rs1881457, and 1E) IL8:rs12506479

Acknowledgements

Appreciation is expressed to the Moffitt Cancer Registry (Director: Karen A. Coyne) for contribution in data abstraction, curation, and management.

Funding

This work was supported by the following funding sources: James & Esther King Biomedical Research Program Grant (09KN-15), National Institutes of Health Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) Grant (P50 CA119997), American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant (93-032-13), National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute American Recovery & Reinvestment Act (ARRA) Grant (5 UC2 CA 148322-02), and National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Grant (1R21CA184996-01). This work has also been supported in part by the Tissue Core Facility at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

Footnotes

Conflicts

None.

Disclosures

Dr. Matthew Schabath is an Associate Editor for Molecular Carcinogenesis, but this does not alter our adherence to the Editorial policies of Molecular Carcinogenesis.

References

- 1.McErlean A, Ginsberg MS. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Semin Roentgenol. 2011;46:173–177. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J, Wu N, Zheng Q, et al. Evaluation of the 7th edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer at a single institution. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:1189–1195. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer JD, Zaorsky NG, Witek M, Lu B. Molecular markers to predict clinical outcome and radiation induced toxicity in lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:387–398. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.12.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li T, Kung HJ, Mack PC, Gandara DR. Genotyping and genomic profiling of non-small-cell lung cancer: implications for current and future therapies. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1039–1049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordon-Cardo C, Prives C. At the crossroads of inflammation and tumorigenesis. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1367–1370. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.10.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dranoff G. Cytokines in cancer pathogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu X, Wang L, Ye Y, et al. Genome-wide association study of genetic predictors of overall survival for non-small cell lung cancer in never smokers. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4028–4038. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang YT, Heist RS, Chirieac LR, et al. Genome-wide analysis of survival in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2660–2667. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu L, Wu C, Zhao X, et al. Genome-wide association study of prognosis in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5507–5514. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu X, Ye Y, Rosell R, et al. Genome-wide association study of survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:817–825. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenstermacher DA, Wenham RM, Rollison DE, Dalton WS. Implementing personalized medicine in a cancer center. Cancer J. 2011;17:528–536. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318238216e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson AD, Handsaker RE, Pulit SL, et al. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2938–2939. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chelala C, Khan A, Lemoine NR. SNPnexus: a web database for functional annotation of newly discovered and public domain single nucleotide polymorphisms. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:655–661. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Z, Taylor JA. SNPinfo: integrating GWAS and candidate gene information into functional SNP selection for genetic association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W600–605. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyle AP, Hong EL, Hariharan M, et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012;22:1790–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the bootstrap. Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalemkerian GP, Jasti RK, Celano P, et al. All-trans-retinoic acid alters myc gene expression and inhibits in vitro progression in small cell lung cancer. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu Z, Taylor JA. SNPinfo: integrating GWAS and candidate gene information into functional SNP selection for genetic association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W600–605. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, et al. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D109–114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang B, Kirov S, Snoddy J. WebGestalt: an integrated system for exploring gene sets in various biological contexts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W741–748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellhammer DH, Buchtal J, Gutberlet I, Kirschbaum C. Social hierarchy and adrenocortical stress reactivity in men. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1997;22:643–650. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maeda S, Hsu LC, Liu H, et al. Nod2 mutation in Crohn’s disease potentiates NF-kappaB activity and IL-1beta processing. Science. 2005;307:734–738. doi: 10.1126/science.1103685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reyes-Gibby CC, Spitz M, Wu X, et al. Cytokine genes and pain severity in lung cancer: exploring the influence of TNF-alpha-308 G/A IL6-174G/C and IL8-251T/A. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2745–2751. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw AD, Vaporciyan AA, Wu X, et al. Inflammatory gene polymorphisms influence risk of postoperative morbidity after lung resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1704–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hildebrandt MA, Komaki R, Liao Z, et al. Genetic variants in inflammation-related genes are associated with radiation-induced toxicity following treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reyes-Gibby CC, El Osta B, Spitz MR, et al. The influence of tumor necrosis factor-alpha -308 G/A and IL-6 -174 G/C on pain and analgesia response in lung cancer patients receiving supportive care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3262–3267. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang YC, Sung WW, Wang L, et al. Different impact of IL10 haplotype on prognosis in lung squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2729–2735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pu X, Ye Y, Spitz MR, et al. Predictors of survival in never-smokers with non-small cell lung cancer: a large-scale, two-phase genetic study. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5983–5991. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richmond J, Tuzova M, Cruikshank W, Center D. Regulation of cellular processes by interleukin-16 in homeostasis and cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:139–147. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan D, Zeng X, Yu H, et al. Role of cytokine gene polymorphisms on prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma after radical surgery resection. Gene. 2014;544:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee KM, Shen M, Chapman RS, et al. Polymorphisms in immunoregulatory genes, smoky coal exposure and lung cancer risk in Xuan Wei, China. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1437–1441. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Z, Liang Y, Qin B, Zhong R. Meta-analysis of the association between the IL-12B +1188 A/C polymorphism and cancer risk. Onkologie. 2013;36:470–475. doi: 10.1159/000354671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hussain SK, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, et al. Nucleotide variation in IL-10 and IL-12 and their receptors and cervical and vulvar cancer risk: a hybrid case-parent triad and case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:201–213. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang ZQ, Wang JL, Pan GG, Wei YS. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in IL-12 and IL-27 genes with colorectal cancer risk. Clin Biochem. 2012;45:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Del Vecchio M, Bajetta E, Canova S, et al. Interleukin-12: biological properties and clinical application. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4677–4685. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawaguchi Y, Tochimoto A, Hara M, et al. Contribution of single nucleotide polymorphisms of the IL1A gene to the cleavage of precursor IL-1alpha and its transcription activity. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:441–448. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0213-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee S, Temple S, Roberts S, Price P. Complex effects of IL1A polymorphism and calpain inhibitors on interleukin 1 alpha (IL-1 alpha) mRNA levels and secretion of IL-1 alpha protein. Tissue Antigens. 2008;72:67–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2008.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dominici R, Cattaneo M, Malferrari G, et al. Cloning and functional analysis of the allelic polymorphism in the transcription regulatory region of interleukin-1 alpha. Immunogenetics. 2002;54:82–86. doi: 10.1007/s00251-002-0445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gorlov IP, Gorlova OY, Frazier ML, et al. Evolutionary evidence of the effect of rare variants on disease etiology. Clin Genet. 2011;79:199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. ENCODE results for lung cell line experiments for 1A) IL12A:rs662959, 1B) IL1B:rs1143634, 1C), IL1A:rs1800587, 1D) IL13:rs1881457, and 1E) IL8:rs12506479